Key Points

Question

Is prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab associated with improvement in visual acuity in eyes with plaque-irradiated uveal melanoma?

Findings

In a cohort study of 1131 eyes with plaque-irradiated uveal melanoma treated with intravitreal bevacizumab at 4-month intervals for 2 years, visual outcome was better at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years, with 4-year median visual acuity of 20/70 compared with counting fingers in a nonrandomized, control (nonbevacizumab) group.

Meaning

These findings suggest prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab may be associated with improved visual outcome up to 4 years for patients with irradiated uveal melanoma.

Abstract

Importance

Radiation retinopathy following plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma can lead to vision loss that might be avoided with prophylactic anti–vascular endothelial growth factor treatment.

Objective

To determine visual outcome following prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab in patients with plaque-irradiated uveal melanoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective, nonrandomized, interventional cohort study at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Prophylactic bevacizumab was administered between 2008 and 2018 to 1131 eyes with irradiated uveal melanoma (bevacizumab group) and compared with 117 eyes with irradiated uveal melanoma between 2007 and 2009 (no bevacizumab [historical control] group).

Interventions

Prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab was provided at the time of plaque removal as well as 6 subsequent injections at 4-month intervals over 2 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Visual acuity.

Results

The median patient age was 61 years, 1195 of 1248 patients were white (96%), and 632 of 1248 were women (51%). The median tumor thickness was 4.0 mm, and median distance to foveola was 3.0 mm. A difference was not identified (bevacizumab vs control group) in demographic features, clinical features, or radiation parameters. The mean follow-up was 40 months vs 56 months (mean difference, −18; 95% CI, −24 to −13; P < .001). By survival analysis, the bevacizumab group demonstrated less optical coherence tomography evidence of cystoid macular edema at 24 months (28% vs 37%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.2; P = .02) and 36 months (44% vs 54%; HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P = .01), less clinical evidence of radiation maculopathy at 24 months (27% vs 36%; HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0-2.2; P = .03), 36 months (44% vs 55%; HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0; P = .01), and 48 months (61% vs 66%; HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .03), and less clinical evidence of radiation papillopathy at 18 months (6% vs 12%; HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-3.9; P = .04). Nonparametric analysis documented better visual acuity outcomes in the bevacizumab group at all points, including 12 months (median logMAR visual acuity [Snellen equivalent]: 0.30 [20/40] vs 0.48 [20/60]; mean difference, −0.28; 95% CI, −0.48 to −0.07; P = .02), 24 months (0.40 [20/50] vs 0.70 [20/100]; mean difference, −0.52; 95% CI, −0.75 to −0.29; P < .001), 36 months (0.48 [20/60] vs 1.00 [20/200]; mean difference, −0.49; 95% CI, −0.76 to −0.21; P = .003), and 48 months (0.54 [20/70] vs 2.00 [counting fingers]; mean difference, −0.71; 95% CI, −1.03 to −0.38; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings from a retrospective cohort of plaque radiotherapy and prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab in patients with uveal melanoma suggest better visual outcomes when compared with nonrandomized historical control individuals through 4 years.

This cohort study investigates 4-year visual outcomes following prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab, injected at 4-month intervals over 2 years, in patients with plaque-irradiated uveal melanoma.

Introduction

Visual outcome following plaque radiotherapy of choroidal melanoma depends on several factors, including patient age, general health, visual acuity, tumor location/size, subretinal fluid, radioactive isotope, and ultimately radiation retinopathy and papillopathy.1 In a consecutive case study1 of 1106 patients with uveal melanoma of random size treated with plaque radiotherapy (in the prebevacizumab era), ultimate visual acuity was poor at 20/200 or worse in 34% at 5 years and 68% at 10 years. Results of the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study2 for medium-size uveal melanoma in 623 patients at 3 years revealed reduction in visual acuity, from visual acuity greater than 20/200 to visual acuity of 20/200 or less in 43% and loss of at least 6 lines of vision in 49%. These poor visual results extend even to the smallest tumors (≤ 3-mm thickness) in 1780 cases that demonstrated Kaplan-Meier 10-year estimates of poor visual acuity (≤20/200) at 54%, despite low risk for metastasis at 9%.3

Since 2008, we have been using prophylactic anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections (bevacizumab) to minimize visual loss following plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma. In 2014,4 we published initial 2-year results suggesting favorable reduction in radiation adverse effects on visual acuity. Herein, we explore our longer experience of 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 4-year results.

Methods

In this study, patients with posterior uveal melanoma treated with plaque radiotherapy and prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab were included. The 2-year duration for injections was selected based on peak time for radiation maculopathy (12 months) and radiation papillopathy (18 months) from the pre–anti-VEGF era.1,2,5,6,7,8,9,10 These patients were compared with historical control individuals prior to bevacizumab. The study was approved by the Wills Eye Hospital institutional review board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients at first examination.

Study Participants

Medical records of all patients with ciliary body or choroidal melanoma treated with iodine-125 plaque radiotherapy at the Ocular Oncology Service, Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between February 1, 2008, and January 19, 2018, were reviewed. All patients 18 years or older were candidates for off-label bevacizumab injection in this clinical outcomes study. Patients in the treatment group received bevacizumab injection (1.25 mg in 0.05 mL) at plaque removal, followed by repeated intravitreal bevacizumab in the office every 4 months for 2 years. Patients with cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or those with previous retinal surgery were excluded from this protocol. In most instances, the bevacizumab was provided by our team, but owing to travel or patient health, injection was occasionally delivered near the home using similar dose and technique. The authors cannot determine with certainty from this real-world analysis exactly how many examinations and 4-month suggested injections of bevacizumab were missed.

Evaluation

All patients underwent ophthalmic examination including slitlamp biomicroscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and ophthalmic imaging with photography, ultrasonography, fundus autofluorescence, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and fluorescein angiography (when indicated) at initial visit and every 4 months in the first 2 years after plaque radiotherapy thereafter.

The standard technique of injection included topical anesthesia with proparacaine eyedrops, placement of sterile eyelid speculum by gloved/masked physician, aseptic preparation of injection site with povidone-iodine, 5%, applied as eyedrop, and injection of bevacizumab with a 30-gauge needle using a trans pars plana approach. Postinjection examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy was performed. On follow-up, patients with OCT-evident macular edema at any time during follow-up were offered therapeutic dose anti-VEGF, including monthly intravitreal bevacizumab, ranibizumab, or aflibercept.

Control Group

A nonrandomized historical control group consisted of 117 patients with ciliary body or choroidal melanoma treated in a similar fashion with plaque radiotherapy without prophylactic bevacizumab between December 1, 2007, and May 31, 2009. These patients received standard-dose plaque radiotherapy and no additional bevacizumab and were monitored identical to patients in the prophylactic bevacizumab group.

Data Collection

The data were collected at each examination. The demographic features included age, race/ethnicity, sex, study eye, medical history, and ocular history. The clinical features at initial examination included best-corrected visual acuity, presenting symptom(s), and tumor features including distance (in millimeters) to optic nerve, distance to foveola, largest basal diameter (in millimeters), tumor thickness (in millimeters), Bruch membrane rupture, sentinel vessels, extraocular extension, and tumor location. The imaging features at initial presentation included ultrasonographic, OCT, and fundus autofluorescence findings. The tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of uveal melanoma, eighth edition.11,12,13 The plaque radiotherapy features included treatment duration, plaque shape, and total dose (gray) and dose rate (gray per hour) to tumor and retina.

Clinical outcomes included follow-up time, best-corrected visual acuity, visual acuity lines lost, final tumor basal diameter and thickness, and the development of OCT-evident cystoid macular edema (CME), clinically evident radiation maculopathy, radiation papillopathy, nonproliferative or proliferative radiation retinopathy, retinal vascular accident, neovascular glaucoma, cataract, and scleral necrosis. Optical coherence tomography–evident CME was defined as presence of cystoid spaces within the macular region. Note that OCT evidence of subclinical macular edema (macular thickening without cystoid spaces) was not included. Clinically evident radiation maculopathy was defined as ophthalmoscopic detection of any of the following findings including macular edema, hemorrhage, exudation, or nerve fiber layer infarction. Clinically evident radiation papillopathy was defined as ophthalmoscopic detection of any of the following findings including optic disc congestion, edema, pallor, or peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer infarction or hemorrhage. Poor visual acuity was defined as final visual acuity at 20/200 or worse on the Snellen visual acuity chart.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc). A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and all P values were 2-sided. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (median, range) unless otherwise indicated. One sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of variables in our sample. Comparisons between 2 groups (bevacizumab vs historical control [nonbevacizumab]) were performed using student independent sample t test for continuous variables with normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables without normal distribution. The χ2 test and Fisher exact test when indicated were used for comparison of categorical variables between 2 groups. Multivariate linear regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed to adjust for the effect of potential confounders on continuous and nominal dependent variables, respectively. For variables without normal distribution, logarithm transformation of the variable was entered in the regression model. Kaplan-Meier estimates and life tables were depicted, and the estimated risk of radiation maculopathy, radiation papillopathy, OCT-evident CME, and poor visual acuity over 48 months’ follow-up were compared between the 2 groups using Breslow test. Hazard ratio (HR) of bevacizumab-free protocol was calculated at 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 36, and 48 months’ follow-up after adjusting for potential confounders using Cox regression analysis.

Results

In this analysis, there were 1131 eyes of 1131 patients in the bevacizumab group and 117 eyes of 117 patients in the nonrandomized historical control group. Patient demographics are listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement. A difference was not identified in comparison (bevacizumab vs control group) in age at presentation, race/ethnicity, sex, affected eye, or medical or ocular history.

Clinical features at presentation are listed in Table 1. A difference was not identified in entering visual acuity, tumor proximity to optic disc or foveola, tumor basal diameter or thickness, tumor location, or extent of subretinal fluid by quadrants. There was a difference in symptoms of reduced vision (34% vs 45%; P = .03; χ2 test), despite measured visual acuity with no difference identified.

Table 1. Clinical Features.

| Clinical Features | Group, No. (%) | Difference, Mean (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (n = 1131) | Control (n = 117) | |||

| Snellen visual acuity | ||||

| No. of eyes | 1248 | NA | NA | NA |

| 20/20 to 20/40 | 774 (68) | 75 (64) | NA | .63 |

| 20/50 to 20/150 | 266 (24) | 31 (27) | ||

| 20/200 or worse | 91 (8) | 11 (9) | ||

| Visual acuity | ||||

| Snellen | ||||

| Median | 20/30 | 20/40 | NA | NA |

| Mean (range) | 20/50 (20/20 to LP) | 20/50 (20/20 to LP) | NA | NA |

| LogMAR | ||||

| Median | 0.18 | 0.30 | −0.03 (−0.13 to 0.07) | .20a |

| Mean (range) | 0.35 (0.00 to 4.00) | 0.38 (0.00 to 4.00) | ||

| Symptoms | ||||

| Decreased visual acuity | 380 (34) | 53 (45) | NA | .03b |

| Visual field defect | 100 (9) | 10 (9) | ||

| Flashes, floaters | 244 (22) | 22 (19) | ||

| Pain | 22 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| No symptoms | 385 (34) | 31 (26) | ||

| Tumor features | ||||

| Distance to optic nerve, mm | ||||

| Mean | 4.6 | 4.8 | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) | .64 |

| Median (range) | 3.5 (0.0 to 20.0) | 4.0 (0.0 to 18.0) | ||

| Distance to foveola, mm | ||||

| Mean | 4.2 | 4.0 | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.1) | .58 |

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0.0 to 20.0) | 3.0 (0.0 to 15.0) | ||

| Tumor basal diameter, mm | ||||

| Mean | 11.5 | 11.5 | 0.0 (−0.8 to 0.8) | .99 |

| Median (range) | 11.0 (2.0 to 22.0) | 11.0 (4.0 to 20.0) | ||

| Tumor thickness, mm | ||||

| Mean | 4.8 | 5.1 | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) | .27 |

| Median (range) | 4.0 (0.9 to 13.3) | 4.4 (1.4 to 12.5) | ||

| Bruch membrane rupture | 118 (10) | 19 (16) | NA | .06 |

| Sentinel vessels | 61 (5) | 11 (9) | NA | .08 |

| Extraocular extension | 10 (1) | 3 (3) | NA | .09 |

| Tumor epicenter | ||||

| Macula | 208 (18) | 13 (11) | NA | .18 |

| Macula to equator | 714 (63) | 75 (64) | ||

| Equator to ora serrata | 168 (15) | 25 (21) | ||

| Ciliary body | 40 (4) | 4 (3) | ||

| Iris | 1 (<1) | 0 | ||

| Quadrantic location | ||||

| Macula | 185 (16) | 12 (10) | NA | .71 |

| Inferior | 205 (18) | 21 (18) | ||

| Temporal | 311 (28) | 29 (25) | ||

| Superior | 252 (22) | 36 (31) | ||

| Nasal | 178 (16) | 19 (16) | ||

| Anterior tumor margin | ||||

| Macula | 62 (6) | 6 (5) | NA | .53 |

| Macula to equator | 467 (41) | 44 (38) | ||

| Equator to ora serrata | 379 (34) | 36 (31) | ||

| Ciliary body | 222 (20) | 31 (27) | ||

| Iris | 1 (<1) | 0 | ||

| Tumor configuration by ultrasonography | ||||

| Dome | 918 (81) | 99 (85) | NA | .84 |

| Mushroom | 126 (11) | 11 (9) | ||

| Plateau | 76 (7) | 7 (6) | ||

| Bilobed or multilobed | 11 (1) | 0 | ||

| Subretinal fluid by OCT | ||||

| Absent | 257 (23) | 27 (23) | NA | .93 |

| Present | 874 (77) | 90 (77) | ||

| Extent of subretinal fluid | ||||

| Subretinal cap over melanoma | 190 (17) | 11 (10) | NA | .003b |

| From tumor margin | ||||

| ≤3 mm | 316 (28) | 30 (26) | ||

| 3-6 mm | 109 (10) | 23 (20) | ||

| >6 mm | 259 (23) | 26 (22) | ||

| Quadrant of subretinal fluid | ||||

| First | 575 (51) | 55 (47) | NA | .09 |

| Second | 208 (18) | 19 (16) | ||

| Third | 75 (7) | 15 (13) | ||

| Fourth | 16 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Subfoveal fluid | 320 (28) | 45 (39) | .03b | |

| Orange pigment by autofluorescence (n = 1108)c | ||||

| No. | 994 | 114 | NA | .004b |

| Absent | 352 (35) | 56 (49) | ||

| Present | 642 (65) | 58 (51) | ||

| Extent of orange pigment, % of tumor surface | ||||

| <25 | 171 (17) | 7 (6) | NA | .05 |

| 25-50 | 164 (16) | 17 (15) | ||

| 50-75 | 184 (19) | 24 (21) | ||

| >75 | 123 (12) | 10 (9) | ||

| AJCC classification, eighth edition | ||||

| I | 426 (38) | 41 (35) | NA | .03b |

| IIA | 416 (37) | 37 (32) | ||

| IIB | 181 (16) | 16 (14) | ||

| IIIA | 82 (7) | 20 (17) | ||

| IIIB | 24 (2) | 3 (3) | ||

| IIIC | 1 (<1) | 0 | ||

| IV | 1 (<1) | 0 | ||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee Cancer; LP, light perception; NA, not applicable; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

By Mann-Whitney U test.

Significant P value.

One hundred thirty-seven patients in the treatment group and 3 patients in the control group had incomplete, poor, or no view of tumor with autofluorescence.

Plaque radiotherapy features are listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement. A difference was not identified (bevacizumab vs control group) in the treatment duration or dose/dose rate to tumor apex, tumor base, optic disc, foveola, and opposite retina. There was a difference in that the control group received higher mean scleral dose (184 Gy vs 212 Gy; P = .002; t test) and scleral dose rate (185 Gy/h vs 209 Gy/h; P = .001, t test).

Clinical outcomes are listed in Table 2. A difference was not identified (bevacizumab vs control group) in final tumor basal diameter, thickness, recurrence, or need for enucleation. The bevacizumab group had shorter mean follow-up (40 months vs 58 months; P < .001; t test), but mean times to detection of retinal radiation complications were 27 months to 35 months (Table 2). Differences were found with the bevacizumab group demonstrating better median visual acuity by logMAR (Snellen equivalent) (0.54 [20/70] vs 1.3 [20/200]; P < .001, Mann-Whitney U test), visual acuity in 20/20 to 20/40 range (n = 419 of 1131 [37%] vs n = 31 of 117 [27%]; P = .002; χ2 test), and loss of fewer Snellen visual acuity lines (median) (2 vs 5; P = .01; Mann-Whitney U test). After adjusting for potential confounders (including age, logMAR visual acuity at presentation, subretinal fluid extension, subfoveal fluid, distance to foveola, dose to apex, base, and foveola) using multivariate linear regression analysis, we found that eyes in bevacizumab group were still associated with better visual acuity at final visit.

Table 2. Clinical Outcomes.

| Clinical Outcomes | Group, No. (%) | Difference, Mean (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (n = 1131) | Control (n = 117) | |||

| Follow-up time, mo | ||||

| Mean | 40 | 58 | −18 (−24 to −13) | <.001a |

| Median (range) | 34 (3 to 117) | 61 (3 to 130) | ||

| Enucleation | 15 (1) | 3 (3) | NA | .44 |

| Snellen visual acuity | ||||

| No. | 1116 | 114 | NA | .002a |

| 20/20 to 20/40 | 419 (37) | 31 (27) | ||

| 20/50 to 20/150 | 299 (27) | 24 (21) | ||

| 20/200 or worse | 398 (36) | 59 (52) | ||

| Visual acuity (Snellen) | ||||

| Median | 20/70 | 20/200 | NA | NA |

| Mean (range) | 20/200 (20/20 to NLP) | CF (20/20 to NLP) | ||

| Visual acuity (logMAR) | ||||

| Median | 0.54 | 1.30 | −0.49 (−0.71 to −021) | <.001a,b |

| Mean (range) | 1.02 (0.00 to 5.00) | 1.53 (0.00 to 5.00) | ||

| Lines of visual acuity loss at last follow-up date | ||||

| Median | 2 | 5 | −1 (−2 to 0) | .01a,b |

| Mean (range) | 4 (0 to 14) | 5 (0 to 14) | ||

| Tumor features | ||||

| Tumor basal diameter, mm | ||||

| Mean | 10.5 | 9.9 | 0.7 (−0.1 to 1.4) | .09 |

| Median (range) | 10.0 (1.0 to 20.0) | 10.0 (2.0 to 20.0) | ||

| Tumor thickness, mm | ||||

| Mean | 2.6 | 2.5 | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .23 |

| Median (range) | 2.2 (0.5 to 12.0) | 2.0 (1.0 to 9.8) | ||

| Recurrence of tumor | 23 (2) | 5 (4) | NA | .18 |

| Time to recurrence, mo | ||||

| Mean | 28 | 62 | −34 (−55 to −14) | .01a |

| Median (range) | 20 (4 to 80) | 67 (27 to 92) | ||

| Radiation complications | ||||

| Cystoid macular edema by OCT | 413 (37) | 58 (50) | NA | .01a |

| Time to onset of cystoid macular edema, mo | ||||

| Mean | 27 | 27 | 0 (−6 to 5) | .84 |

| Median (range) | 22 (3 to 98) | 20 (3 to 104) | ||

| Radiation maculopathy | 431 (38) | 59 (50) | NA | .01a |

| Time to radiation maculopathy, mo | ||||

| Mean | 29 | 27 | 1 (−3 to 6) | .58 |

| Median (range) | 24 (4 to 114) | 20 (4 to 68) | ||

| Radiation papillopathy | 197 (17) | 31 (27) | NA | .02a |

| Time to radiation papillopathy, mo | ||||

| Mean | 30 | 27 | 2 (−4 to 8) | .47 |

| Median (range) | 27 (2 to 93) | 21 (4 to 72) | ||

| Nonproliferative radiation retinopathy | 269 (24) | 40 (34) | NA | .01a |

| Time to nonproliferative radiation retinopathy, mo | ||||

| Mean | 28 | 27 | 0 (−5 to 6) | .88 |

| Median (range) | 24 (4 to 97) | 21 (4 to 72) | ||

| Proliferative radiation retinopathy | 7 (1) | 7 (6) | NA | <.001a |

| Time to proliferative radiation retinopathy, mo | ||||

| Mean | 33 | 35 | −1 (−25 to 22) | .92 |

| Median (range) | 36 (3 to 55) | 26 (11 to 72) | ||

| Retinal vessel occlusion | ||||

| Branch retinal vein occlusion | 310 (27) | 42 (36) | NA | .43 |

| Central retinal vein occlusion | 7 (1) | 0 | ||

| Branch retinal artery occlusion | 8 (1) | 0 | ||

| Time to retinal vessel occlusion, mo | ||||

| Mean | 27 | 33 | −6 (−12 to 0) | .07 |

| Median (range) | 23 (3 to 103) | 35 (4 to 88) | ||

| Neovascularization of the iris | 31 (3) | 7 (6) | NA | .05 |

| Time to neovascularization of the iris, mo | ||||

| Mean | 33 | 29 | 4 (−13 to 21) | .66 |

| Median (range) | 33 (4 to 69) | 22 (11 to 75) | ||

| Neovascular glaucoma | 32 (3) | 7 (6) | NA | .06 |

| Time to neovascular glaucoma, mo | ||||

| Mean | 38 | 33 | 5 (−15 to 25) | .63 |

| Median (range) | 34 (4 to 96) | 22 (11 to 86) | ||

| Cataract | 302 (27) | 45 (38) | NA | .01a |

| Time to cataract, mo | ||||

| Mean | 27 | 27 | −1 (−7 to 6) | .81 |

| Median (range) | 21 (2 to 138) | 24 (2 to 79) | ||

| Scleral necrosis | 12 (1) | 3 (3) | NA | .39 |

| Time to scleral necrosis, mo | ||||

| Mean | 40 | 34 | 5 (−23 to 34) | .70 |

| Median (range) | 35 (8 to 81) | 33 (10 to 60) | ||

Abbreviations: CF, counting fingers; NLP, no light perception; NA, not applicable; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Significant P value

By Mann-Whitney U test.

Radiation complications are listed in Table 2. Comparison (bevacizumab vs control group) revealed that the bevacizumab group had lower rate of OCT-evident CME, radiation maculopathy, radiation papillopathy, nonproliferative radiation retinopathy, and proliferative radiation retinopathy. After adjusting for potential confounders (including age, tumor thickness/diameter, distance to foveola/disc, dose to apex/base, foveola, and disc) using binary logistic regression analysis, we found that the bevacizumab group demonstrated reduction in the probability of CME, radiation maculopathy, radiation papillopathy, and proliferative radiation retinopathy. There was no difference regarding development of non-proliferative radiation retinopathy. A difference was not identified between the 2 groups regarding development of retinal vascular occlusion, neovascularization of the iris, neovascular glaucoma, cataract, scleral necrosis, or tumor recurrence. The mean time to tumor recurrence was shorter in the bevacizumab group (28 months vs 62 months; P = .01). A difference was not identified in mean time to development of CME, radiation maculopathy, radiation papillopathy, nonproliferative/proliferative radiation retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusion, NVI, neovascular glaucoma, cataract, or scleral necrosis.

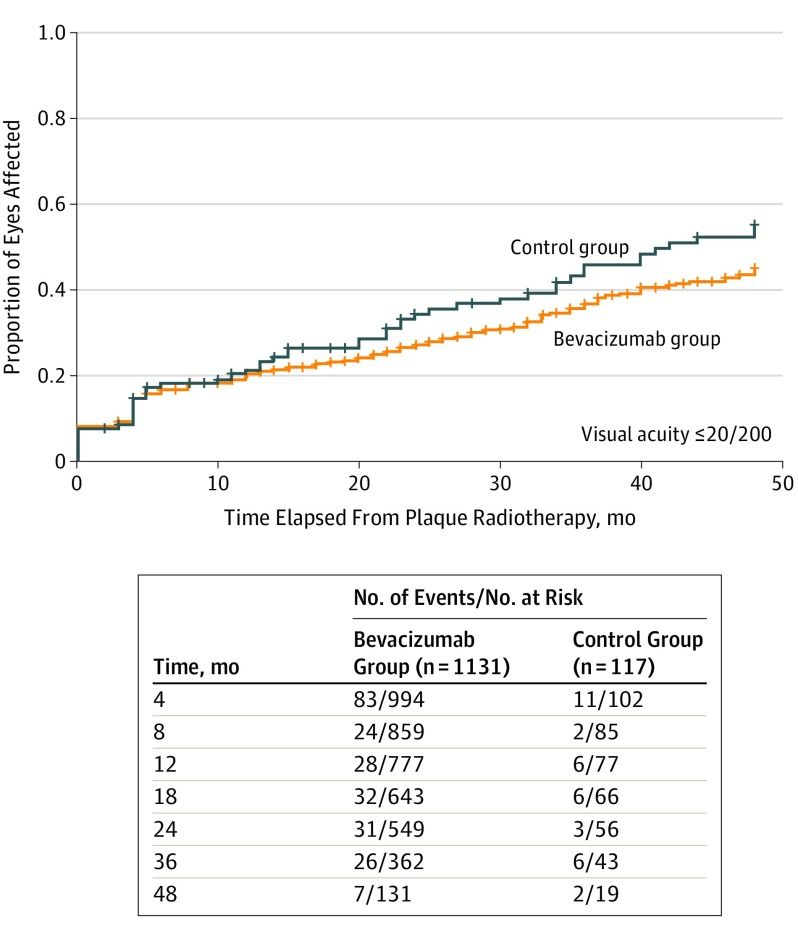

Outcomes by survival analysis are listed in Table 3 as comparison (bevacizumab vs control group). Using life table analysis and Cox regression analysis, after adjusting for potential confounders, the bevacizumab group was associated with reduced cumulative probability of OCT-evident CME at 4 months, 24 months, and 36 months (eFigure 1A in the Supplement). The bevacizumab group was associated with reduced cumulative probability of clinically evident radiation maculopathy at 24 months, 36 months, and 48 months (eFigure 1B in the Supplement) and reduced cumulative probability of radiation papillopathy at 4 months and 18 months (eFigure 1C in the Supplement). Bevacizumab was not associated with cumulative probability for development of poor VA (≤20/200) any point during follow-up (Figure). The number of patients with available follow-up in each group at the investigated points are shown in eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Outcomes by Survival Analysis.

| Time, mo | Group, No. of Events/No. at Risk (%) | HR (95% CI)a | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (n = 1131) | Control (n = 117) | |||

| OCT-evident cystoid macular edema | ||||

| 4 | 20/1069 (2) | 7/109 (6) | 3.49 (1.48-8.26) | .002 |

| 8 | 74/1017 (7) | 13/107 (12) | 1.80 (1.0-3.24) | .05 |

| 12 | 121/950 (13) | 18/100 (18) | 1.54 (0.94-2.52) | .08 |

| 18 | 178/878 (20) | 25/95 (26) | 1.44 (0.94-2.18) | .09 |

| 24 | 221/792 (28) | 33/90 (37) | 1.52 (1.10-2.19) | .02 |

| 36 | 296/667 (44) | 45/83 (54) | 1.53 (1.12-2.09) | .01 |

| 48 | 353/593 (60) | 48/81 (59) | 1.30 (0.99-1.81) | .06 |

| Clinically evident radiation maculopathy | ||||

| 4 | 4/1074 (0) | 0/113 | 23.24 (0.00->10 000) | .52 |

| 8 | 29/1023 (3) | 2/106 (2) | 1.48 (0.35-6.22) | .59 |

| 12 | 77/951 (8) | 9/99 (10) | 1.15 (0.58-2.30) | .69 |

| 18 | 140/877 (16) | 20/93 (22) | 1.41 (0.88-2.25) | .15 |

| 24 | 215/807 (27) | 32/88 (36) | 1.50 (1.03-2.17) | .03 |

| 36 | 308/695 (44) | 45/82 (55) | 1.48 (1.08-2.02) | .01 |

| 48 | 373/612 (61) | 52/79 (66) | 1.39 (1.04-1.86) | .03 |

| Clinically evident radiation papillopathy | ||||

| 4 | 5/1069 (0) | 3/109 (3) | 5.92 (1.41-24.76) | .02 |

| 8 | 14/1016 (1) | 3/105 (3) | 2.12 (0.61-7.38) | .24 |

| 12 | 30/944 (3) | 3/98 (3) | 1.00 (0.30-3.25) | .99 |

| 18 | 54/862 (6) | 11/89 (12) | 2.02 (1.06-3.87) | .04 |

| 24 | 86/761 (11) | 14/82 (17) | 1.63 (0.93-2.87) | .09 |

| 36 | 134/594 (23) | 19/77 (25) | 1.36 (0.84-2.21) | .20 |

| 48 | 173/481 (36) | 22/74 (30) | 1.12 (0.72-1.75) | .62 |

| Visual acuity ≤20/200 | ||||

| 4 | 166/1186 (14) | 17/112 (15) | 1.00 (0.61-1.64) | .99 |

| 8 | 199/1048 (19) | 21/108 (19) | 1.03 (0.66-1.61) | .90 |

| 12 | 226/989 (23) | 24/101 (24) | 1.04 (0.68-1.58) | .85 |

| 18 | 253/917 (28) | 29/96 (30) | 1.13 (0.77-1.65) | .55 |

| 24 | 285/852 (33) | 36/90 (40) | 1.24 (0.88-1.76) | .21 |

| 36 | 350/724 (48) | 45/86 (52) | 1.26 (0.92-1.71) | .14 |

| 48 | 393/640 (61) | 52/85 (61) | 1.26 (0.95-1.69) | .11 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

aAnalysis by Cox regression analysis. Hazard ratio reflects the absence of prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab injections.

bP value level of significance is less than .05, Breslow test.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Poor Visual Acuity Outcome (≤20/200) After Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Uveal Melanoma.

Comparison of patients treated with prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab at 4-month intervals for a duration of 2 years vs control individuals treated with observation alone revealed no difference in Kaplan-Meier–estimated poor visual outcome (61% vs 61%; hazard ratio, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.95-1.69; P = .11) at 4 years.

The visual acuity outcome (mean, median, and range) at each time interval over 48 months is listed in Table 4. Comparison (bevacizumab vs control group) revealed the bevacizumab group with better median logMAR (Snellen equivalent) visual acuity at 4 months (0.18 [20/30] vs 0.30 [20/40]; P = .04), 12 months (0.30 [20/40] vs 0.48 [20/60]; P = .02), 18 months (0.40 [20/50] vs 0.70 [20/100]; P = .003), 24 months (0.40 [20/50] vs 0.70 [20/100]; P < .001), 36 months (0.48 [20/60] vs 1.00 [20/200]; P = .003), and 48 months (0.54 [20/70], vs 2.00 [counting fingers]; P < .001).

Table 4. Visual Acuity Outcomes at Specific Intervals Up to 4 Years.

| Time From Plaque Radiotherapy, mo | Visual Acuity | Difference, Mean (95% CI) | P Valuea,b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab | Control | |||||||||

| LogMAR | Snellen Equivalent | LogMAR | Snellen Equivalent | |||||||

| Median | Mean (Range) | Median | Mean (Range) | Median | Mean (Range) | Median | Mean (Range) | |||

| 4 | 0.18 | 0.48 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/30 | 20/60 (20/20 to NLP) | 0.30 | 0.67 (0.00 to 4.00) | 20/40 | 20/100 (20/20 to LP) | −0.19 (−0.33 to −0.05) | .04 |

| 8 | 0.30 | 0.50 (0.00 to 4.00) | 20/40 | 20/60 (20/20 to LP) | 0.30 | 0.68 (0.00 to 4.00) | 20/40 | 20/100 (20/20 to LP) | −0.18 (−0.35 to −0.01) | .09 |

| 12 | 0.30 | 0.61 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/40 | 20/80 (20/20 to NLP) | 0.48 | 0.89 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/60 | 20/150 (20/20 to NLP) | −0.28 (−0.48 to −0.07) | .02 |

| 18 | 0.40 | 0.71 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/50 | 20/100 (20/20 to NLP) | 0.70 | 1.18 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/100 | 20/400 (20/20 to NLP) | −0.48 (−0.74 to −0.21) | .003 |

| 24 | 0.40 | 0.75 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/50 | 20/100 (20/20 to NLP) | 0.70 | 1.27 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/100 | 20/400 (20/20 to NLP) | −0.52 (−0.75 to −0.29) | <.001 |

| 36 | 0.48 | 0.95 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/60 | 20/200 (20/20 to NLP) | 1.00 | 1.43 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/200 | 20/400 (20/20 to NLP) | −0.49 (−0.76 to −0.21) | .003 |

| 48 | 0.54 | 1.13 (0.00 to 5.00) | 20/70 | 20/200 (20/20 to NLP) | 2.00 | 1.84 (0.00 to 5.00) | CF | CF (20/20 to NLP) | −0.71 (−1.03 to −0.38) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CF, counting fingers; LP, light perception; NLP, no light perception.

Analysis by t test.

P values are significant at less than .05, by Mann-Whitney U test.

After adjusting for potential confounders (logMAR visual acuity at initial presentation; age; radiation dose to apex, base, and fovea; tumor distance to the foveola; presence of subfoveal fluid; and tumor basal diameter and thickness), using multivariate linear regression, the association between intravitreal bevacizumab and better visual acuity remained at 4 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, 36 months, and 48 months. There was no instance of ocular or systemic adverse drug reaction related to intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in any patient.

Discussion

In 2000, Shields et al1 published an analysis of visual outcome in 1106 consecutive patients with uveal melanoma treated with plaque radiotherapy, and multivariable analysis revealed several factors associated with poor visual acuity (≤20/200) including patient age of 60 years or older, poor initial visual acuity, greater tumor thickness, tumor proximity 5 mm or less to the foveola, presence of subretinal fluid, and others. Poor visual outcome (≤20/200) at 5 years was found in 24% of those with small melanoma, 30% with medium melanoma, and 64% with large melanoma.1 Subsequently, in 2001, the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study2 provided a 3-year analysis on visual outcome following plaque radiotherapy of medium-size choroidal melanoma and found visual acuity 20/200 or less (43%) or at least 6 lines of visual acuity loss (49%).2 Similar factors for poor visual outcome were noted.2 Both of these studies were published prior to our understanding of the effect of ischemia-driven VEGF in the development of radiation maculopathy and prior to the availability of intravitreal anti-VEGF medications.

In 2006, Missotten et al14 studied VEGF factor A (VEGF-A) in 74 eyes with untreated uveal melanoma, 8 eyes with treated uveal melanoma, and 30 control eyes. By comparison (eyes with untreated melanoma vs control eyes) they found elevated aqueous VEGF-A concentration (median, 146.5 pg/mL vs 50.1 pg/mL, P < .001). Those with treated uveal melanoma demonstrated median aqueous VEGF-A concentration of 364 pg/mL and those with clinically evident radiation retinopathy revealed the highest median VEGF-A levels of 1877.5 pg/mL, ranging up to 3000.0 pg/mL in 1 eye following proton beam radiotherapy.14 Association of VEGF-A level with tumor basal diameter (P < .001) and thickness (P = .001) was documented. Based on this knowledge, we believed that intervention with anti-VEGF medication could be beneficial in reducing VEGF levels and vision loss.

In 2014, our team published what is, to our knowledge, the first protocol series4 on prophylactic (every 4 months) anti-VEGF for prevention of macular edema after plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma. In that analysis (bevacizumab group [n = 292] vs control group [n = 126]), the outcomes favored the bevacizumab group with cumulative 2-year incidence of OCT-evident macular edema (26% vs 40%; P = .004), clinically evident radiation maculopathy (16% vs 31%; P = .001), moderate vision loss (33% vs 57%; P < .001), and poor visual acuity (≤20/200) (15% vs 28%; P = .004). Kaplan-Meier estimates at 2 years showed reduced rates in the bevacizumab group of OCT-evident macular edema and clinically evident radiation maculopathy. Similar findings were published by Kim et al15 using every-2-months ranibizumab following proton beam radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma. A comparison (ranibizumab group vs matched control individuals) revealed favorable findings in the ranibizumab group, with 2-year visual acuity of at least 20/40 (77% vs 22%; P < .001) and clinically evident radiation maculopathy in the small/medium tumors (33% vs 68%; P = .004).15 The authors suggested that this approach was safe and carried a high rate of visual acuity retention.

In this analysis, we studied a cohort of 1131 eyes in which intravitreal bevacizumab was given at the time of plaque removal and every 4 months up to 2 years and found (Table 3) that the effect of bevacizumab was favorable in reduction of OCT-evident CME at 2 years and 3 years; reduction in clinically evident radiation maculopathy at 2 years, 3 years, and 4 years; and reduction in clinically evident radiation papillopathy at 1.5 years. Regarding visual acuity, those eyes in the bevacizumab group demonstrated better median visual acuity at all points, especially at 4 years (20/70 vs counting fingers; P < .001). This indicates that the use of intravitreal bevacizumab during the early 2-year postradiotherapy, at peak time for the development of radiation maculopathy and papillopathy,9,10 can have lasting protection on visual acuity. However, it should be noted that there was no difference in the outcome of poor visual acuity (≤20/200) at each point, likely associated with macular ischemia with retinal atrophy in these clinically similar groups.

We have used this information to construct a nomogram that is predictive of visual outcome following plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma and prophylactic bevacizumab (available at https://fighteyecancer.com/nomograms/).16 This nomogram takes into account clinical and treatment factors, and, when including the most important factors for poor visual acuity outcome (<20/200) of entering visual acuity of 20/30 or less (100 points), tumor basal diameter greater than 11 mm (80 points), radiation dose rate to tumor base of at least 164 cGy/h (78 points), tumor thickness greater than 4 mm (76 points), insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes (75 points), and abnormal foveolar status on OCT (72 points), the risk for poor visual acuity at 2 and 4 years increased from 6% and 14%, with total 56 points to 88% and 99% with 496 points, respectively.16

Limitations

There are limitations to this analysis. This large cohort extends for more than 10 years and represents real-world data in that all included patients were advised intravitreal prophylaxis, and most patients complied; however, for various reasons, some patients missed appointments. Additionally, we made comparison with nonrandomized historical control individuals, and the lack of a randomized control group precludes determining with certainty whether the differences are owing to other differences between the groups, and further studies to minimize this bias would be needed to support our conclusions. Further, the control group demonstrated greater length of follow-up than the bevacizumab group, which could have affected clinical outcomes as a whole, especially visual acuity. However, Kaplan-Meier visual outcomes demonstrated that the bevacizumab group indeed outperformed the control group at each point. It should additionally be understood that despite evidence that radiation-related macular ischemia is common following plaque radiotherapy and more than 50% of patients lose visual acuity by 3 to 4 years,1,2,3 there are some patients who might not have achieved any benefit from intravitreal bevacizumab. Another limitation regards guidelines on the accurate definition of Gray/centiGray by the American College of Radiology in 2007.17,18 We adjusted numerical radiation values to achieve equivalent radiation dose/dose rate to tumor apex and other structures in the treated eyes to match the 2007 definition.17

Conclusions

In summary, this cohort study suggests a benefit to prophylactic treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab, given every 4 months, for a period of 2 years following plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma. We found reduction in radiation maculopathy, papillopathy, and visual acuity loss, and this was maintained, to some degree, up to 4 years following radiotherapy. Future studies on longer-term anti-VEGF medications or those with different binding affinities or dosing alterations could reveal more robust associations with visual acuity protection.

eTable 1. Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Bevacizumab (Every 4 Months for 2 Years) for Uveal Melanoma in 1131 Eyes of 1131 Patients: Demographic Features

eTable 2. Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Bevacizumab (Every 4 Months for 2 Years) for Uveal Melanoma in 1131 Patients: Plaque Radiotherapy Features

eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Radiation Side Effects After Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Uveal Melanoma

eFigure 2. Number of Patients with Available Follow-up Over the Course of Four Years After Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Uveal Melanoma

References

- 1.Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma: long-term visual outcome in 1106 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1219-1228. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.9.1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for medium choroidal melanoma: I. visual acuity after 3 years: COMS report no. 16. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:348-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields CL, Sioufi K, Srinivasan A, et al. Visual outcome and millimeter incremental risk of metastasis in 1780 patients with small choroidal melanoma managed by plaque radiotherapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(12):1325-1333. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah SU, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab at 4-month intervals for prevention of macular edema after plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):269-275. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields JA, Shields CL. Intraocular Tumors: an Atlas and Textbook. 3rd ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Wolters Kluwer; 2016:179. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunduz K, Shields CL. Radiation retinopathy and papillopathy In: Yanoff M, Duker J, eds. Ophthalmology. 5th edition 2018 Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders Co; 2018:567-574. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horgan N, Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Teixeira LF, Materin MA, Shields JA. Early macular morphological changes following plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma. Retina. 2008;28(2):263-273. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31814b1b75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horgan N, Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Classification and treatment of radiation maculopathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(3):233-238. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283386687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown GC, Shields JA, Sanborn G, Augsburger JJ, Schatz NJ, Savino PJ. Radiation retinopathy. Trans Pa Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1981;34(2):144-151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown GC, Shields JA, Sanborn G, Augsburger JJ, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ. Radiation optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(12):1489-1493. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(82)34612-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivelä T, Simpson ER, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Uveal melanoma In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed New York, NY: Springer; 2017:805-817. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40618-3_67 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Fulco E, Alarcon C, Shields JA. American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of posterior uveal melanoma (tumor size category) predicts prognosis in 7731 patients. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2066-2071. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Fulco E, Alarcon C, Shields JA. American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of uveal melanoma (anatomic stage) predicts prognosis in 7731 patients: the 2013 Zimmerman Lecture. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(6):1180-1186. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Missotten GS, Notting IC, Schlingemann RO, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor a in eyes with uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(10):1428-1434. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.10.1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim IK, Lane AM, Jain P, Awh C, Gragoudas ES. Ranibizumab for the prevention of radiation complications in patients treated with proton beam irradiation for choroidal melanoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2016;114:T2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalvin LA, Zhang Q, Costello R, et al. Nomogram for visual acuity outcome after Iodine-125 plaque radiotherapy and prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab for uveal melanoma in 1131 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Amis ES Jr, Butler PF, Applegate KE, et al. ; American College of Radiology . American College of Radiology white paper on radiation dose in medicine. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4(5):272-284. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stecker MS, Balter S, Towbin RB, et al. ; SIR Safety and Health Committee; CIRSE Standards of Practice Committee . Guidelines for patient radiation dose management. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20(7)(suppl):S263-S273. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Bevacizumab (Every 4 Months for 2 Years) for Uveal Melanoma in 1131 Eyes of 1131 Patients: Demographic Features

eTable 2. Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Bevacizumab (Every 4 Months for 2 Years) for Uveal Melanoma in 1131 Patients: Plaque Radiotherapy Features

eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Radiation Side Effects After Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Uveal Melanoma

eFigure 2. Number of Patients with Available Follow-up Over the Course of Four Years After Plaque Radiotherapy and Prophylactic Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Uveal Melanoma