Abstract

This survey study assesses who has primary care in the United States and how this has changed over time.

Receipt of primary care is associated with better health.1,2 Despite the benefits of primary care, Americans’ receipt of primary care, changes in receipt of primary care over time, and differences in receipt of primary care according to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are not well known.

Methods

We analyzed data from the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (21 915-26 509 individuals yearly) from 2002 through 2015. We used a patient-centered definition of primary care that included the 4 C’s of primary care: first contact, comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous. To estimate factors associated with receiving primary care over time, we used multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for each year from 2002 through 2015;sociodemographic and clinical variables, presented in the Table; and the complex survey design. We examined having primary care over time by decade of age and stratified by comorbidity. We performed all analyses with SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute). The Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board approved this study and determined it not to be human subject research, so patient informed consent was waived.

Table. Nationally Representative Sample of Adult Americans With and Without Primary Care, 2002-20151.

| Characteristic | Respondents, % (95% CI) | All Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2015 | ||||||

| Total (n = 24 537) | Primary Care | Total (n = 22 835) | Primary Care | Adjusted Odds of Having Primary Care, aOR (95% CI)a | |||

| With (n = 18 366) | Without (n = 6171) | With (n = 16 460) | Without (n = 6375) | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| 20s | 20 (20-21) | 60 (57-62) | 40 (38-43) | 20 (19-21) | 56 (54-59) | 44 (41-46) | 1 [Reference] |

| 30s | 20 (20-21) | 71 (69-73) | 29 (27-31) | 17 (16-18) | 64 (61-67) | 36 (33-39) | 1.22 (1.17-1.28) |

| 40s | 21 (20-22) | 79 (77-80) | 21 (20-23) | 17 (16-18) | 75 (73-77) | 25 (23-27) | 1.61 (1.53-1.69) |

| 50s | 17 (16-17) | 85 (84-87) | 15 (13-16) | 19 (18-20) | 82 (81-84) | 18 (16-19) | 1.84 (1.73-1.94) |

| 60s | 10 (10-11) | 91 (89-92) | 9 (8-11) | 15 (14-15) | 89 (88-91) | 11 (9-12) | 2.25 (2.09-2.43) |

| 70s | 8 (7-8) | 95 (93-96) | 5 (4-7) | 8 (7-9) | 93 (91-94) | 7 (6-9) | 2.79 (2.49-3.11) |

| ≥80s | 4 (3-4) | 94 (92-96) | 6 (4-8) | 4 (4-5) | 95 (93-97) | 5 (3-7) | 2.74 (2.33-3.22) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 52 (51-52) | 82 (81-83) | 18 (17-19) | 51 (51-52) | 80 (79-81) | 20 (19-21) | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 48 (48-49) | 72 (70-73) | 28 (27-30) | 49 (48-49) | 70 (68-71) | 30 (29-32) | 0.59 (0.57-0.60) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Latino white | 71 (69-72) | 82 (81-83) | 18 (17-19) | 64 (62-66) | 79 (78-81) | 21 (19-22) | 1 [Reference] |

| Latino | 12 (11-13) | 58 (55-61) | 42 (39-45) | 16 (14-18) | 64 (62-66) | 36 (34-38) | 0.80 (0.77-0.84) |

| Black | 11 (10-12) | 73 (70-76) | 27 (24-30) | 12 (11-13) | 71 (69-73) | 29 (27-31) | 0.88 (0.84-0.93) |

| Asian | 4 (3-5) | 68 (63-73) | 32 (27-37) | 6 (5-7) | 74 (71-77) | 26 (23-29) | 0.67 (0.62-0.74) |

| Other or multiracial | 2 (2-2) | 74 (69-79) | 26 (21-31) | 3 (2-4) | 74 (68-79) | 26 (21-32) | 1.03 (0.84-1.25) |

| US Census Bureau region | |||||||

| Northeast | 19 (18-21) | 85 (83-87) | 15 (13-17) | 18 (16-20) | 81 (78-84) | 19 (16-22) | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest | 23 (21-24) | 80 (78-82) | 20 (18-22) | 21 (20-23) | 80 (78-82) | 20 (18-22) | 0.78 (0.71-0.87) |

| South | 36 (34-38) | 74 (72-76) | 26 (24-28) | 37 (35-39) | 71 (69-72) | 29 (28-31) | 0.53 (0.48-0.58) |

| West | 22 (21-24) | 73 (71-75) | 27 (25-29) | 24 (22-25) | 74 (72-76) | 26 (24-28) | 0.64 (0.58-0.70) |

| Partner status | |||||||

| Married/ partnered |

56 (55-57) | 81 (80-83) | 19 (17-20) | 53 (52-55) | 80 (79-81) | 20 (19-21) | 1 [Reference] |

| Widowed | 7 (7-7) | 91 (90-93) | 9 (7-10) | 6 (5-6) | 91 (89-93) | 9 (7-11) | 0.71 (0.64-0.77) |

| Divorced/ separated |

13 (12-13) | 73 (71-75) | 27 (25-29) | 13 (12-13) | 77 (75-79) | 23 (21-25) | 0.72 (0.69-0.76) |

| Never married | 24 (23-25) | 64 (63-66) | 36 (34-37) | 28 (27-29) | 62 (60-64) | 38 (36-40) | 0.76 (0.73-0.80) |

| Education | |||||||

| <High school | 22 (21-22) | 73 (71-75) | 27 (25-29) | 14 (13-14) | 71 (69-73) | 29 (27-31) | 1 [Reference] |

| High school/GED/some college | 54 (54-55) | 77 (76-78) | 23 (22-24) | 56 (55-58) | 75 (73-76) | 25 (24-27) | 1.19 (1.14-1.24) |

| Bachelor degree | 15 (14-15) | 80 (78-82) | 20 (18-22) | 19 (18-20) | 76 (74-79) | 24 (21-26) | 1.09 (1.02-1.16) |

| >Bachelor degree | 9 (9-10) | 83 (80-85) | 17 (15-20) | 11 (11-12) | 80 (78-83) | 20 (17-22) | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) |

| Health insurance coverage | |||||||

| Any private | 74 (73-75) | 82 (81-83) | 18 (17-19) | 70 (69-71) | 78 (77-79) | 22 (21-23) | 1 [Reference] |

| Public only | 13 (13-14) | 85 (83-87) | 15 (13-17) | 21 (20-22) | 81 (79-83) | 19 (17-21) | 0.84 (0.79-0.90) |

| Uninsured | 13 (12-14) | 44 (41-46) | 56 (54-59) | 9 (9-10) | 42 (38-45) | 58 (55-62) | 0.29 (0.27-0.30) |

| Perceived health status | |||||||

| Excellent | 27 (26-28) | 72 (70-73) | 28 (27-30) | 27 (26-28) | 69 (67-70) | 31 (30-33) | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 33 (32-34) | 77 (76-79) | 23 (21-24) | 34 (33-35) | 75 (73-76) | 25 (24-27) | 1.13 (1.09-1.17) |

| Good | 27 (26-28) | 78 (77-80) | 22 (20-23) | 26 (25-27) | 78 (76-80) | 22 (20-24) | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) |

| Fair | 10 (9-10) | 85 (83-87) | 15 (13-17) | 10 (9-11) | 83 (81-85) | 17 (15-19) | 1.07 (1.00-1.14) |

| Poor | 3 (3-4) | 91 (89-92) | 9 (8-11) | 3 (3-3) | 88 (85-91) | 12 (9-15) | 0.99 (0.89-1.09) |

| Employment | |||||||

| Not employed | 28 (27-29) | 86 (84-87) | 14 (13-16) | 30 (29-31) | 85 (84-86) | 15 (14-16) | 1 [Reference] |

| Employed | 72 (71-73) | 74 (73-75) | 26 (25-27) | 70 (69-71) | 71 (70-72) | 29 (28-30) | 0.88 (0.85-0.92) |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Nonsmoker | 79 (79-80) | 79 (78-80) | 21 (20-22) | 87 (86-87) | 76 (75-77) | 24 (23-25) | 1 [Reference] |

| Smoker | 21 (20-21) | 71 (69-73) | 29 (27-31) | 13 (13-14) | 69 (66-71) | 31 (29-34) | 0.77 (0.74-0.81) |

| ADL help | |||||||

| No help | 97 (97-98) | 77 (76-78) | 23 (22-24) | 97 (96-97) | 75 (74-76) | 25 (24-26) | 1 [Reference] |

| Help | 3 (2-3) | 93 (90-95) | 7 (5-10) | 3 (3-4) | 91 (89-94) | 9 (6-11) | 0.97 (0.83-1.15) |

| IADL help | |||||||

| No help | 95 (95-95) | 76 (75-77) | 24 (23-25) | 95 (94-95) | 74 (73-76) | 26 (24-27) | 1 [Reference] |

| Help | 5 (5-5) | 92 (90-94) | 8 (6-10) | 5 (5-6) | 90 (87-92) | 10 (8-13) | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) |

| Chronic diseasesb | |||||||

| 0 | 60 (59-61) | 68 (66-69) | 32 (31-34) | 51 (50-52) | 62 (60-63) | 38 (37-40) | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 22 (22-23) | 87 (86-88) | 13 (12-14) | 19 (18-20) | 82 (80-84) | 18 (16-20) | 2.26 (2.17-2.35) |

| 2 | 10 (10-11) | 94 (93-95) | 6 (5-7) | 12 (11-13) | 92 (91-93) | 8 (7-9) | 4.02 (3.77-4.30) |

| ≥3 | 8 (7-9) | 97 (96-98) | 3 (2-4) | 18 (17-19) | 95 (93-96) | 5 (4-7) | 5.40 (5.00-5.82) |

| Income | |||||||

| Poor | 10 (10-11) | 68 (65-70) | 32 (30-35) | 11 (11-12) | 67 (64-70) | 33 (30-36) | 1 [Reference] |

| Near poor | 4 (4-4) | 70 (67-74) | 30 (26-33) | 4 (3-4) | 69 (66-73) | 31 (27-34) | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) |

| Low | 13 (12-14) | 70 (68-73) | 30 (27-32) | 13 (12-14) | 70 (68-72) | 30 (28-32) | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) |

| Middle | 31 (30-32) | 77 (75-78) | 23 (22-25) | 28 (27-29) | 74 (72-75) | 26 (25-28) | 1.25 (1.19-1.32) |

| High | 42 (40-43) | 82 (81-84) | 18 (16-19) | 43 (42-45) | 81 (79-82) | 19 (18-21) | 1.55 (1.47-1.64) |

| PCS, mean (95% CI)c | 49 (49-49) | NA | NA | 50 (49-50) | NA | NA | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) |

| MCS, mean (95% CI)c | 51 (51-51) | NA | NA | 52 (52-52) | NA | NA | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) |

| BMI, mean (95% CI)c | 27 (27-27) | NA | NA | 28 (28-28) | NA | NA | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); GED, general educational development; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MCS, Mental Composite Score (of the short-form-24); NA, not applicable; PCS, Physical Composite Score (of the short-form-24).

Adjusted for each year from 2002 through 2015 and all variables in the Table.

Of the 20 conditions considered chronic by the US Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health.

Percentages and means were weighted to be nationally representative and account for nonresponse. Percentages may not sum to 100 owing to rounding.

Results

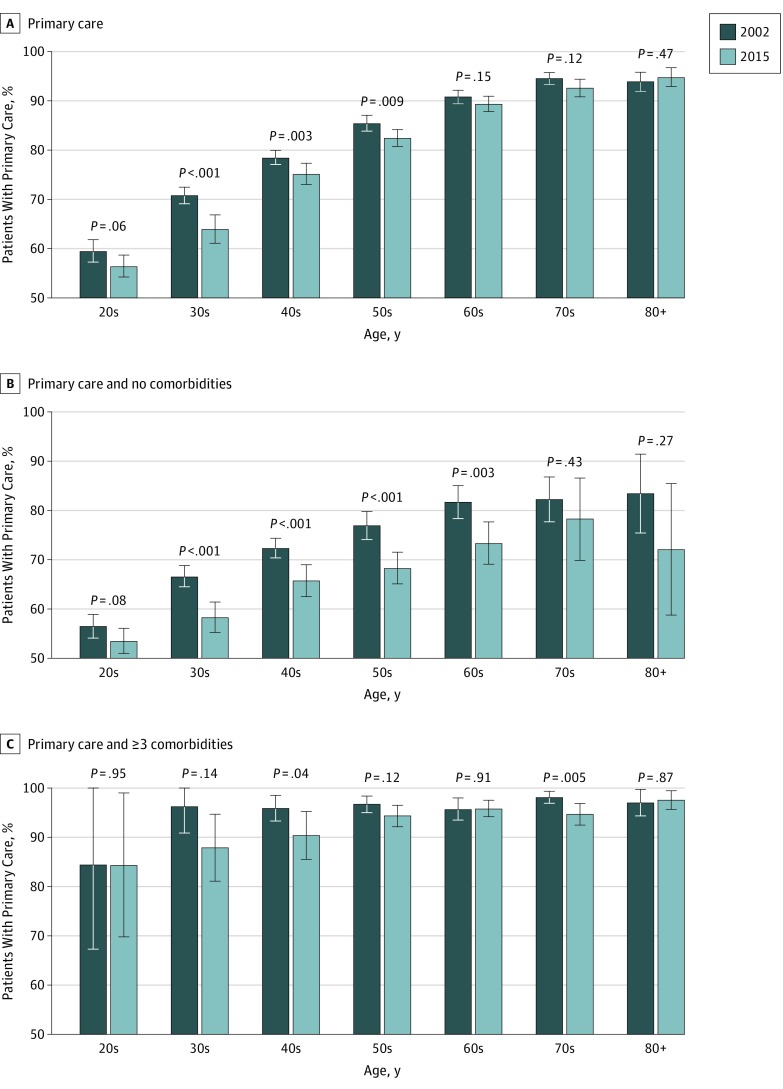

The proportion of adult Americans with an identified source of primary care decreased from 77% (95% CI, 76%-78%) in 2002 to 75% (95% CI, 74%-76%) in 2015 (odds ratio, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.82-0.98]). During this period, receipt of primary care decreased for every decade of age except for Americans in their 80s, with statistically significant reductions for those in their 30s, 40s, and 50s (Figure, A). For example, 71% of Americans in their 30s had primary care in 2002 compared with 64% in 2015 (P < .001).

Figure. Nationally Representative Sample of Adult Americans With an Identified Source of Primary Care, 2002-2015.

A, Americans with primary care, by age. B, Americans with primary care and no comorbidities, by age. C, Americans with primary care and 3 or more comorbidities, by age. Error bars are unadjusted 95% CIs.

Among Americans with no comorbidities (60% [95% CI, 59%-61%] in 2002 and 51% [95% CI, 50%-52%] in 2015), receipt of primary care decreased for every decade of age (Figure, B). For example, for Americans in their 60s with no comorbidities, having primary care fell from 82% in 2002 to 73% in 2015 (P = .003). Having primary care for Americans with at least 3 comorbidities was generally stable (Figure, C).

In multivariable modeling, factors associated with a decreased likelihood of having primary care included calendar year (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.97 for each year from 2002 through 2015 [95% CI, 0.97-0.98]), male sex (aOR vs female sex, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.57-0.60]), Latino race/ethnicity (aOR vs white, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.77-0.84]), black race/ethnicity (aOR vs white, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.84-0.93]), Asian race/ethnicity (aOR vs white, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.62-0.74]), not having insurance (aOR vs private insurance, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.27-0.30]), and Southern US Census Bureau region (aOR vs Northeast, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.48-0.58]) (Table).

Discussion

From 2002 through 2015, a decreasing proportion of Americans had an identified source of primary care, especially Americans who were younger, less medically complex, of minority background, or living in the South. To improve Americans’ health in an efficient and cost-effective manner, policy makers should prioritize increasing the proportion of Americans with primary care.

The decrease in receipt of primary care, particularly among younger patients or patients with no chronic medical conditions, may be related to their choosing nonlongitudinal interactions over continuity, perhaps related to the convenience revolution3 and a perception that primary care has failed to adopt new modes of delivering treatment that might be more accessible to patients.4,5 Financial barriers, especially among uninsured Americans, may prevent some people from accessing primary care. Shortages in the availability of primary care may pose access barriers even to insured people, with the result that fewer younger and healthier patients have a regular source of care.6

References

- 1.Levine DM, Landon BE, Linder JA. Quality and experience of outpatient care in the United States for adults with or without primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):363-372. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310(1):35-36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linder JA, Levine DM. Health care communication technology and improved access, continuity, and relationships: the revolution will be Uberized. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):643-644. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine DM, Linder JA. Retail clinics shine a harsh light on the failure of primary care access. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):260-262. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3555-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947-956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1612890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]