Abstract

Background

A cervical stitch has been used to prevent preterm deliveries in women with previous second trimester pregnancy losses, or other risk factors such as short cervix on digital or ultrasound examination.

Objectives

To assess effectiveness and safety of prophylactic cerclage (before the cervix has dilated), emergency cerclage (where cervices have started to shorten and dilate) and then labour halted, and to determine whether a particular technique of stitch insertion is better than others.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (July 2002). We handsearched congress proceedings of International and European society meetings of feto‐maternal medicine, recurrent miscarriage and reproductive medicine. We contacted researchers in the field. We updated the search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register on 2 November 2009 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

All randomised trials comparing cervical cerclage with expectant management or no cerclage during pregnancy and trials comparing one technique with another or with other interventions were included. Quasi randomised trials were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently used prepared data extraction forms. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer. Further clarification was sought from trial authors when required. Results were reported as relative risks using fixed or random effects model.

Main results

Six trials with a total of 2175 women were analysed. Prophylactic cerclage was compared with no cerclage in four trials. There was no overall reduction in pregnancy loss and preterm delivery rates, although a small reduction in births under 33 weeks' gestation was seen in the largest trial (relative risks 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 0.98). Cervical cerclage was associated with mild pyrexia, increased use of tocolytic therapy and hospital admissions but no serious morbidity. Two trials examined the role of therapeutic cerclage when ultrasound examination revealed short cervix. Pooled results failed to show a reduction in total pregnancy loss, early pregnancy loss or preterm delivery before 28 and 34 weeks in women assigned to cervical cerclage.

Authors' conclusions

The use of a cervical stitch should not be offered to women at low or medium risk of mid trimester loss, regardless of cervical length by ultrasound. The role of cervical cerclage for women who have short cervix on ultrasound remains uncertain as the numbers of randomised women are too few to draw firm conclusions.

There is no information available as to the effect of cervical cerclage or its alternatives on the family unit and long term outcome.

[Note: The 23 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Plain language summary

Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing pregnancy loss in women

Cervical stitch (cerclage) may help prevent miscarriage due to a cervical factor, but has not been shown to benefit other women.

The cervix (opening of the uterus) normally stays tightly closed during pregnancy. Occasionally it starts to open early, leading to miscarriage. For some women, this recurs in subsequent pregnancies. This may be due to cervical weakness (incompetence) if the miscarriage occurs in the second or early third trimester. One option is cervical cerclage: surgery to insert a suture (stitch) to keep the cervix closed. The review of trials found that there was no overall reduction in pregnancy loss and preterm delivery rates with either a prophylactic or therapeutic cervical stitch for short cervix on ultrasound.

Background

Pregnancy loss at any stage is distressing but especially so when this happens later on in the pregnancy. Extreme prematurity can also have severe implications as babies that survive may have residual handicap. The cervix normally stays tightly closed during pregnancy, with a mucus plug sealing the opening. At the onset of labour, the cervix begins to dilate, ready for the baby to be born. Occasionally the cervix starts to open early in the pregnancy, leading to a miscarriage. For a few women, this process seems to recur in subsequent pregnancies. This may be due to cervical weakness (incompetence) if the miscarriage occurs in the second (12 to 23 weeks 6 days) or early third trimester (after 24 weeks).

Cervical incompetence during pregnancy has been described as early as the seventeenth century (Riverius 1658) and complicates about one per cent of an obstetric population (McDonald 1980) and eight per cent of a recurrent miscarriage population who have suffered mid trimester pregnancy losses (Drakeley 1998). There is, however, no consistent definition of cervical incompetence (Berry 1995) which hampers knowledge of the true incidence.

Some workers have defined cervical incompetence as 'the history of painless dilatation of the cervix resulting in second or early third trimester delivery and the passage without resistance, of size nine Hegar dilator (an instrument which is used to measure the size of cervical dilatation in millimetres i.e. 9mm)". Passage of a 9mm Hegar dilator through the cervix without resistance, in a non‐pregnant women is indicative but not diagnostic of cervical incompetence. Other definitions of cervical incompetence used include: 'recurrent second trimester or early third trimester loss of pregnancy caused by the inability of the uterine cervix to retain a pregnancy until term' (Althuisius 2001a) and 'a physical defect in the strength of the cervical tissue that is either congenital (inherited) or acquired' (caused by previous damage) Rust 2000a. Gestational age distinguishes between a miscarriage (0 to 23 weeks 6 days) and pre‐term labour (24 to 37 completed weeks). In developed/resource rich countries an unborn baby is considered to be viable at 24 weeks and in resource poor/developing countries viability is still 28 weeks.

Pre‐pregnancy diagnostic tests may include hysterosalpingogram (an investigation where dye is passed through the cervix and uterus and x‐ray pictures taken) or more recently transvaginal ultrasonography measuring cervical length. A shortened cervical length may increase the likelihood of preterm labour (Murakawa 1993). The diagnosis is more often based on history of recurrent mid trimester losses (Stirrat 1999) or previous mechanical (physical) dilatation of the cervix during surgery. In the absence of previous surgical trauma (cervical surgery), the underlying pathogenesis of cervical incompetence is often unknown. Cervical incompetence has traditionally been viewed as an 'all or nothing' condition, but the concept of it being a continuum, responsible for some pre‐term deliveries as well as mid‐trimester miscarriages is now gaining in acceptance.

There are a number of proposed treatments designed to keep the cervix closed until the expected time of birth. All interventions require at least regional anaesthesia in the form of a spinal or epidural block. General anaesthetic is also used. Shirodkar 1955 reported the insertion of a cervical stitch (suture) at around 14 weeks of pregnancy. The anterior vaginal wall is cut under anaesthesia and the bladder is reflected (pushed) back and upwards. A stitch (usually silk or other non‐absorbable material) is inserted around the cervix, enclosing it. By this technique, the surgeon can get as close as possible to the level of the internal cervical os by the vaginal route. McDonald 1957 described a simpler purse string stitch technique, whereby the stitch is inserted around the body of the cervix present in the vagina in three or four bites and so approximation to the internal os is less satisfactory, but the procedure is easier to perform with less bleeding. These techniques were described as elective (planned) procedures.

Stitches are normally inserted via the vaginal route, but trans‐abdominal cerclage has been described for women when vaginal stitches have not worked, or where women have short, scarred cervices which make vaginal stitch insertion technically difficult (Gibb 1995; Anthony 1997). At approximately 14 weeks' gestation, the pregnant woman undergoes a formal laparotomy (abdominal operation), the bladder is reflected (pushed) downwards away from the uterus and the cervical stitch is placed at the level of the internal cervical os. Vaginally inserted cervical stitches are either taken out at 37 weeks' gestation, or when the woman presents in labour without an anaesthetic. Abdominal cervical stitches are left in place and the baby delivered by caesarean section. If the woman labours prematurely, the decision to perform laparotomy in advanced labour may be difficult or too late.

Elective cervical cerclage, by whichever technique employed, carries risks for the pregnancy. Surgical manipulation of the cervix can cause uterine contractions, bleeding or infection which may lead to miscarriage or pre‐term labour. These risks have to be carefully balanced against the benefit from mechanical support to the cervix.

Cervical cerclage can either be inserted as a planned procedure based on previous history, or else as an emergency situation when women with threatened miscarriage present at the hospital (Wong 1993; Chanrachakul 1998). Emergency cerclage tends to be performed after 18 weeks' gestation, whilst elective procedures are usually planned around 14 weeks.

Controversies concerning cervical cerclage include effectiveness, safety and risk/benefit to both mother and unborn baby. The avoidance of surgical trauma to the cervix may be as effective as intervention. Grant 1989 reviewed the evidence for the benefits and hazards of treatment by cervical cerclage to prolong pregnancy. He suggested that cervical cerclage in women with a previous mid trimester loss (or preterm delivery) may help to prevent one delivery before 33 weeks for every 20 stitches inserted. Since 1989 there have been a number of randomised and non‐randomised studies published, concerning investigation and intervention. However, the issues surrounding timing of elective cerclage and optimal techniques have not been addressed adequately in the available literature. The evidence on which to base practice for emergency cerclage is even less robust.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness (prevention of pregnancy loss) and safety of prophylactic cervical cerclage (before the cervix has either dilated or shortened) when inserted in women with cervical weakness (incompetence).

To assess the effectiveness and safety of emergency cerclage inserted during mid trimester miscarriage or extreme pre‐term labour.

To assess the effectiveness and safety of elective cerclage used before pregnancy by either the vaginal or abdominal route.

If cervical cerclage is effective, to determine which is the superior technique for insertion.

To assess the role of ultrasound in the selection of women to have a cervical stitch.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised trials comparing cervical cerclage with expectant management or no cerclage during pregnancy and trials comparing one technique with another or with other interventions. Quasi‐randomised studies were excluded (e.g. randomisation by date of birth or hospital number).

Types of participants

Women with confirmed, or suspected of having, cervical incompetence who desire future pregnancies and women who present as an emergency and are thought to have a diagnosis of cervical incompetence. Studies to be considered include those that have made the diagnosis of cervical incompetence from clinical history alone (recurrent mid trimester losses) or by using evidence from cervical resistance studies.

Types of interventions

Comparisons of cervical cerclage by whichever method, with no cerclage or with other interventions to prevent miscarriage or pre‐term labour. Primary comparisons: (a) elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest; (b) elective versus emergency cerclage; (c) emergency cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest; (d) pre‐pregnancy cerclage versus no cerclage; (e) elective cerclage versus other treatments (e.g. pessaries).

Secondary comparisons: (a) Shirodkar versus McDonald technique; (b) transabdominal versus transvaginal methods.

Types of outcome measures

Maternal: (1) maternal mortality; (2) infection ‐ maternal pyrexia and/or sepsis (as defined by trialists) and endotoxic shock; (3) intra‐operative bleeding; (4) pre‐term pre‐labour rupture of membranes (PPROM); (5) mode of delivery ‐ vaginal or caesarean section; (6) induction of labour rate; (7) use of tocolytics ‐ oral or intravenous (drugs used to suppress labour); (8) episodes of suspected pre‐term labour and myometrial activity; (9) use of antenatal steroids; (10) antepartum haemorrhage (as defined by trialists); (11) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by trialists); (12) minor morbidity (e.g. restricted mobility after the procedure); (13) serious morbidity (e.g. admission to intensive care unit, hysterectomy, cervical laceration, cervical dystocia, cervical stenosis, vesico‐vaginal fistula, uterine rupture, anaesthetic complications); (14) women's feelings/emotions about the specific treatments (e.g. bed rest and ability to look after other children); (15) women's satisfaction of different treatments; (16) effect on partner/relationship (e.g. domestic, social, sexual); (17) long term affects (e.g. adjustment to parenthood, effect on the whole family); (18) influence of personal characteristics (e.g. age, ethnicity). Neonatal: (1) Pregnancy loss (not classifiable as stillbirth, as the fetus is non‐viable i.e. before 24 weeks gestation). (2) Peri‐natal death. (3) Pregnancy duration (randomisation to delivery)

by days;

delivery less than 28 weeks' gestation;

delivery less than 32 weeks' gestation;

delivery less than 37 weeks' gestation;

mean gestational age.

(4) Hypoxic Ischaemic Encephalopathy (HIE) (diagnosed by ultrasound or clinically). HIE score describes the degree of lack of oxygen to the brain and is associated with handicap. (5) Neonatal weight. (6) Infant and child development ‐ such as cerebral palsy; mental retardation, hearing and vision as assessed by paediatric follow‐up and attainment of developmental milestones:

less than 1 year;

less than 2 years;

greater than 2 years.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (July 2002). We updated this search on 2 November 2009 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

In addition, we performed handsearches of congress proceedings of the International and European society meetings of feto‐maternal medicine, recurrent miscarriage and reproductive medicine. Whenever possible, we contacted investigators to ask about any additional studies potentially eligible for inclusion.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers performed independently the assessment of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for inclusion in the review . We were not blinded to the authors and institutions of the trials under consideration. Any difference of opinion regarding trials for inclusion were resolved by the third reviewer. If agreement could not be reached, then the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group editor for the review was consulted. The validity of each RCT to be included was assessed according to the criteria in the Cochrane Handbook (Clarke 2000), with a grade allocated to each on the basis of allocation concealment ‐ A (adequate), B (unclear) or C (clearly inadequate). Where the method of allocation concealment was unclear, authors were contacted to provide further details. Quasi‐randomised studies in which allocation was transparent (e.g. use of alternative allocation or medical record numbers) were excluded.

RCTs were excluded if it were not possible to present the data by intention to treat i.e. prescription of cerclage versus no prescription. Completeness of follow‐up was assessed for each outcome. We excluded data for a given outcome if more than 20 per cent of randomised participants were excluded from that outcome.

Two reviewers using previously prepared data extraction forms and performed the data extraction independently. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion. If agreement was not reached, the data were excluded until further clarification was available from the authors. Data presented in graphs and figures were extracted, whenever possible, but was only included if two reviewers independently had the same result. All data entry were double checked for discrepancies. Statistical analyses were performed using the RevMan 4.1 software (RevMan 2000). Results were reported as relative risks, fixed or random effects model, as appropriate.

Sensitivity analysis for the main outcomes was performed by comparing: (1) high quality trials versus low quality RCTs (those in category B and C) for both allocation concealment and completeness of follow‐up; (2) by suture technique (Shirodkar versus McDonald).

This review updates previous versions related to the use of cervical cerclage that were included in the earlier Cochrane Collaboration Pregnancy and Childbirth database (Grant 1995a; Grant 1995b; Grant 1995c; Grant 1995d; Grant 1995e).

Results

Description of studies

Included studies:

Six studies were included in the current review. The UK coordinated MRC/RCOG 1993 trial is the largest randomised controlled trial (RCT) in the review. This international multicentre study recruited women who were deemed at risk of a mid trimester pregnancy loss by history but whose obstetrician was uncertain of the diagnosis of cervical weakness. One thousand two hundred and ninety two women were randomised to stitch versus no stitch. The trial by Rush 1984 was set in a South African teaching hospital miscarriage clinic. It was designed to evaluate whether the policy of prescribing cerclage prolongs gestation in women with a history of late miscarriage. One hundred and niney four women with at least two previous preterm labours or pregnancy loss between 14 and 36 completed weeks were randomised to stitch or no stitch. The French study by Lazar 1984, set in four nearby hospitals, developed a scoring chart for suspected cervical incompetence and included women they deemed at moderate risk of preterm delivery. The scoring system aspects of previous history, state of the cervix and evolving signs of cervical change and vaginal bleeding. Five hundred and six women were included.

A study from the Netherlands (Althuisius 2001a; Althuisius 2001b) initially screened a population of women with previous risk factors of preterm delivery and late miscarriage. This trial used two Amsterdam hospitals. The first RCT describes prophylactic cerclage based on history and reports on 70 women. In the second paper, using the same women, a second randomisation was allowed for the initial 'no stitch' group described if a woman's cervical length became less than 25mm and less than 27 weeks' gestation, in which case women were randomised to either therapeutic cerclage plus bed rest or else bed rest alone. All women were admitted to hospital for five days. For the first two days they had complete bed rest. On the third day they were able to use the bathroom. On the fourth they were allowed to mobilize three times for a quarter of an hour each time. At home, they followed the same policy as day four until 32 weeks. The women were initially randomised to receive a stitch or ultrasound surveillance in a ratio of two to one, and analysis was by intention to treat for both papers. Whilst a pragmatic approach, the design of this study made it difficult for reviewers to enter data as initial randomisation and outcomes were complicated by a second randomisation. We are very grateful to Dr Althuisius who divided the trial data into two separate randomised trials, initial prophylactic and secondary therapeutic.

Rust 2001, from USA, has presented randomised data for 113 women, set in a single tertiary centre. They employed a composite cervical score (Benham score) using dynamic imaging of the cervix and four measurements, again using 25mm distal length as a critical cut off. All women in the Rust 2001 study had amniocentesis prior to randomisation to exclude chorioamnionitis.

Excluded studies:

Three studies have been excluded. Caspi 1990 from Israel used hospital chart numbers for randomisation which was deemed inadequate. Forster 1986 from Germany also used quasi randomisation in the form of initial letter of the woman's surname and so was excluded. Szeverenyi 1992 was published in Hungarian. We contacted the senior author twice but with no reply. We also contacted the English co‐authors who felt that some of the women could well be included in the MRC/RCOG 1993 study.

Ongoing studies:

Nicolaides 2001 from London, UK, has used ultrasound scanning before 23 weeks to screen women for cervical length, using 15mm as a cut off for randomisation (about the fifth percentile). The premise being that the shorter the length of the cervix, the more likely the risk of preterm labour. Trial analysis is incomplete.

(Twenty‐two reports from an updated search in November 2009 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation: Althuisius 2001a; Althuisius 2001b; Lazar 1984; MRC/RCOG 1993; Rush 1984; Rust 2001 all scored A. Althuisius 2001a and Althuisius 2001b used telephone randomisation in balanced blocks. Lazar 1984 used randomly prepared envelopes. MRC/RCOG 1993 used four randomisation centres, by telephone or post, randomising by balanced blocks. Rush 1984 used randomly allocated sealed envelopes. Rust 2001 employed a computer generated random number sequence placed in sealed opaque envelopes.

Blinding: Treatment was not blinded in the included trials, although a 'sham' procedure was employed in one of the excluded trials for the 'no stitch' group.

Effects of interventions

(1) Comparison: elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest.

We have identified four eligible trials (Althuisius 2001a; Lazar 1984; MRC/RCOG 1993; Rush 1984) that compared cerclage with 'expectant' management. Althuisius 2001a screened a population with previous risk factors for preterm delivery and late miscarriage. Lazar 1984 recruited women at moderate risk of cervical incompetence, using a scoring system to assess risk factors. The MRC/RCOG 1993 randomised women for whom the obstetrician was uncertain whether to advise her to have cerclage or not. Rush 1984 recruited women with at least two preterm labours plus one pregnancy loss between 14 and 36 weeks.

Timing of suture insertion was less than 15 weeks' gestation for Althuisius 2001a, under 28 weeks for Lazar 1984 and between 15 and 21 weeks for Rush. MRC/RCOG 1993 did not pre‐specify gestation for cerclage (latest being at 29 weeks).

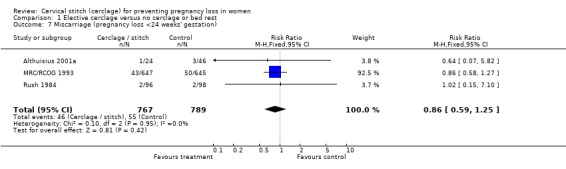

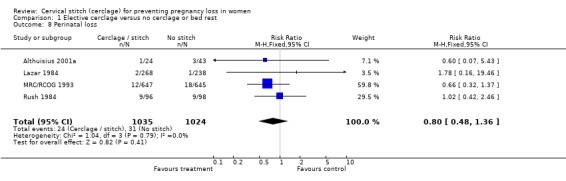

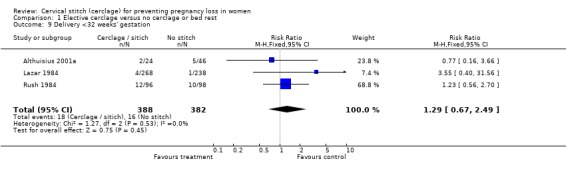

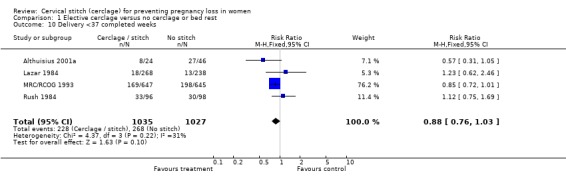

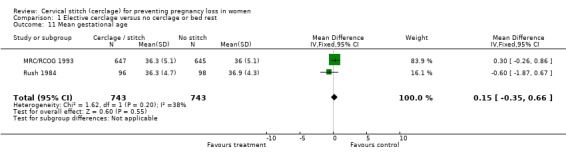

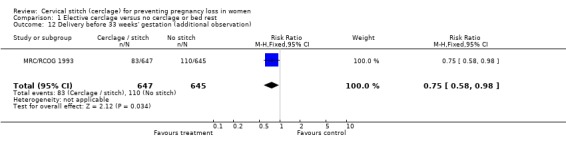

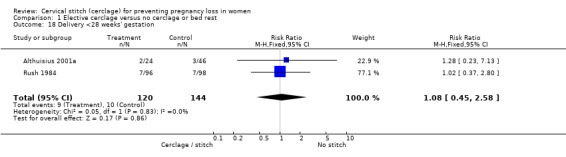

Pooled results show no differences in total pregnancy loss and early pregnancy loss (less than 24 weeks) (relative risk (RR) 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 1.25). Two trials (Althuisius 2001a; Rush 1984) reported on delivery less than 28 weeks' gestation and three trials (Althuisius 2001a; Lazar 1984; Rush 1984) on delivery less than 32 weeks but failed to show beneficial effect of cerclage (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.49). There was also no difference in perinatal death (RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.36), or the mean gestational age weighted mean difference (WMD) 0.15 (95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.66) between the two groups. The MRC/RCOG 1993 trial used 33 weeks' gestation as an important milestone and appeared to suggest fewer deliveries in the cerclage arm (83/647, 12.8% cerclage versus 110/645, 17.1% control; RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.98). All four studies reported on preterm delivery <37 weeks' gestation with no overall significant difference between the two groups (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.03).

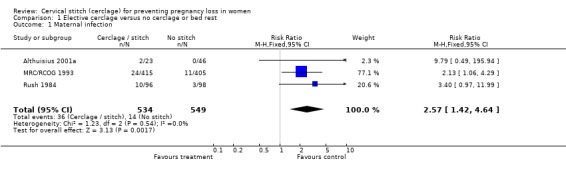

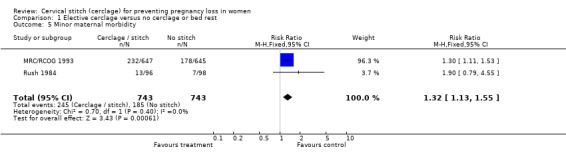

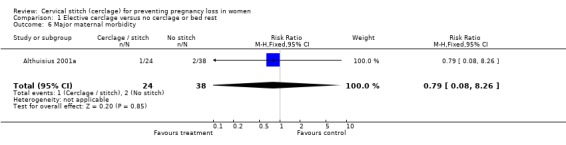

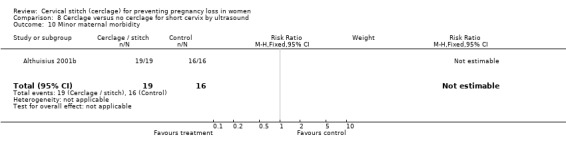

There were no cases of maternal mortality in any of the reported trials. In the Althuisius 2001a trial there was one uterine rupture in the cerclage arm and two major post partum haemorrhages in the control arm. Compared with conservative therapy, more women developed infection (defined as mild pyrexia by the trialists) after cervical stitch (6.7% versus 2.6%; RR 2.57, 95% CI 1.42 to 4.64). Some studies described infection as pyrexia greater than 38 degrees centigrade (Rush 1984; MRC/RCOG 1993), the others were less specific. The MRC/RCOG 1993 has been included despite reporting on less than 80% of randomised participants as this was the only outcome that data were incomplete, and meant that data on 1000 women could be considered instead of 200. Without the MRC/RCOG 1993 trial, the effect is even greater. There was also a higher risk of minor maternal morbidity in the cerclage arm (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.55), which for most studies meant hospital admissions and bed rest.

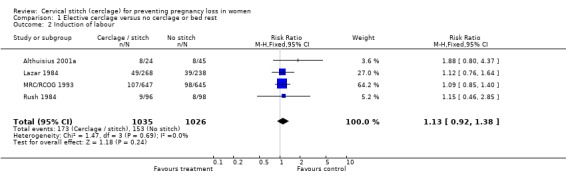

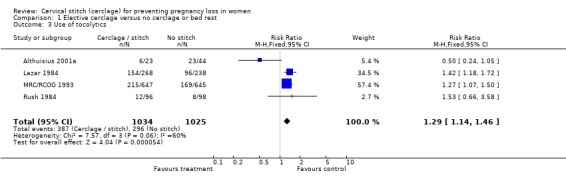

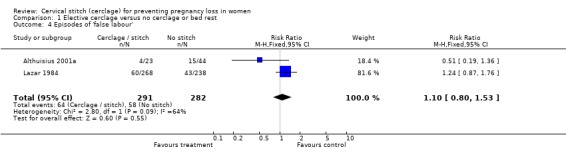

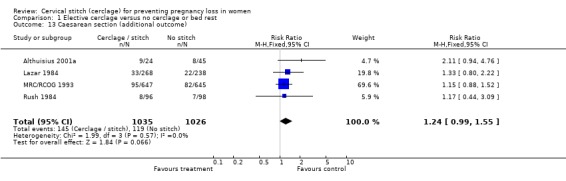

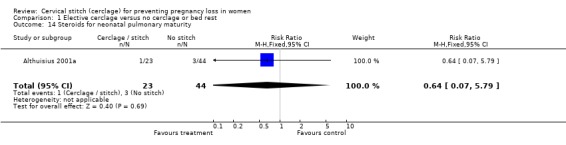

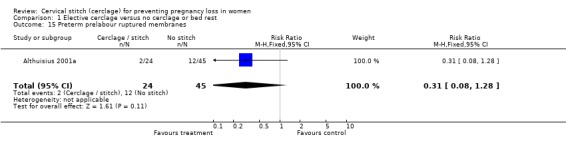

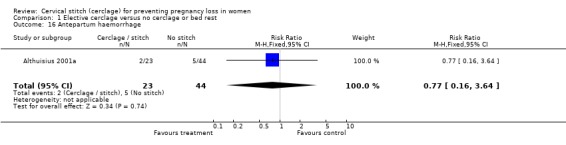

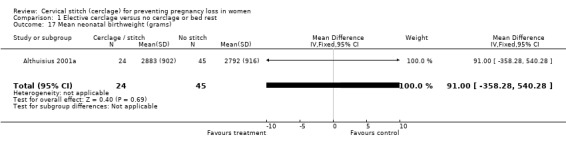

There were more caesarean sections in the cervical suture group (14% versus 11.6%), but this did not reach significance (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.55). No difference in the induction rate was observed (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.38). More tocolytic therapy was prescribed in the cerclage group (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.46). Only Althuisius 2001a reported on steroid use for fetal pulmonary maturity and no difference between the two groups was noted . Althuisius 2001a reported less preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes after cervical suture (8% versus 27%, RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.28). There were no differences in antepartum haemorrhage rates (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.16 to 3.64) and neonatal birth weights were essentially the same WMD 91 (95% CI ‐358 to 540).

(2) Comparison: elective versus emergency cerclage.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(3) Comparison: emergency (rescue cerclage) versus no cerclage or bed rest.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(4) Comparison: pre‐pregnancy cerclage versus no cerclage.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(5) Comparison: elective cerclage versus other treatments.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(6) Comparison: Shirodkar versus McDonald technique.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(7) Comparison: transabdominal versus transvaginal methods.

No trials have examined this comparison.

(8) Additional comparison: Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound.

Two trials investigated ultrasound measurements of cervical length as the indicator for inserting a cervical stitch (Althuisius 2001b; Rust 2001). Althuisius 2001b recruited women at risk of cervical incompetence in whom transvaginal ultrasound revealed 'short' cervix (less than 25mm) before 27 weeks' gestational age. Rust 2001 randomised women between 16 and 24 weeks who had demonstrable prolapse of the fetal membranes into the endocervical canal greater than 25% of the total cervical length or with a distal cervical length less than 25mm according to transvaginal ultrasonography.

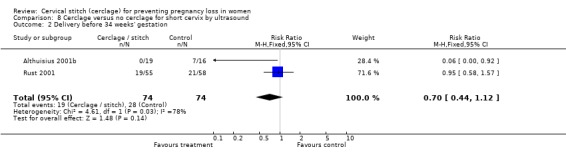

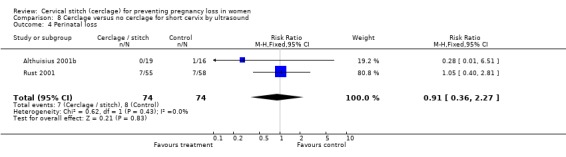

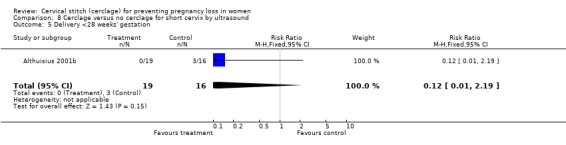

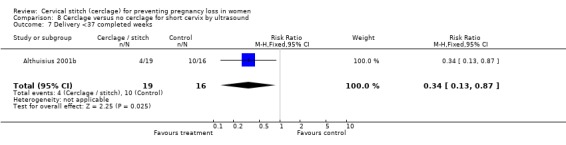

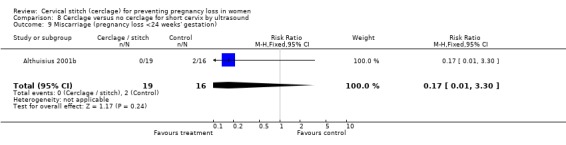

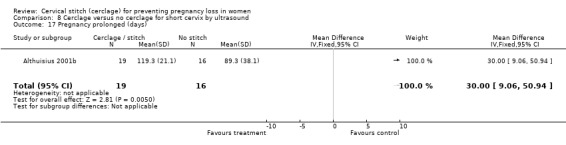

There was no difference in total pregnancy loss (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.27), early pregnancy loss (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.3) or preterm delivery before 28 weeks (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.19) and 34 weeks (RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.12). The data for delivery less than 34 weeks show significant heterogeneity (p = 0.03) and pooled relative risk using random model is 0.31, 95% CI 0.02 to 6.09. Althuisius 2001b reported delivery less than 37 weeks' gestation, favouring cerclage (4/19, 21.1% versus 10/16, 63%; RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.87). The Althuisius 2001b study showed also a significantly longer gestation after cervical stitch (37.9 weeks versus 33.1 weeks). However, when the data from both Althuisius 2001b and Rust 2001 study are combined, the prolongation of gestation was not significant (1.5 weeks 95% CI ‐0.3 to 3.3 weeks).

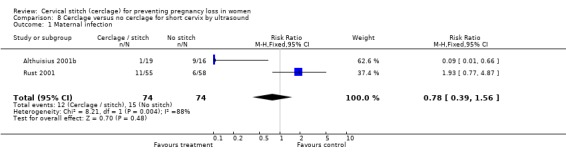

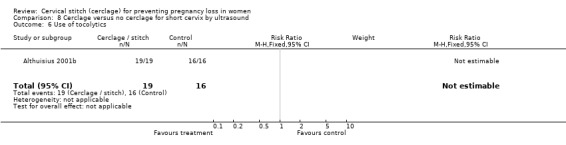

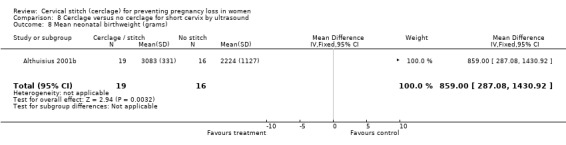

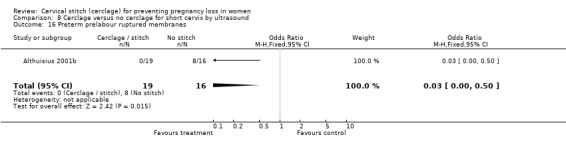

When evaluating maternal infection, the two studies conflict. Althuisius 2001b showed the control group having more infection (1/19, 5.3% cerclage versus 9/16, 56.3% control) but Rust 2001 shows the converse (11/55, 20% cerclage versus 6/58, 10.3% control). The two studies gave prophylactic antibiotics to both groups; the Althuisius 2001b using amoxycillin/clavulanic acid and the Rust 2001 study clindamycin intravenously. Rust 2001 performed amniocentesis to exclude infection prior to inclusion. Althuisius 2001b reported lower incidence of pre‐term pre‐labour rupture of membranes (PPROM) in the cerclage arm (0/19) compared with the no stitch arm (8/16) (RR 0.03, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.50). It is therefore debatable whether these results should be pooled together. The pooled relative risks using fixed effects was 0.78 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.56) and 0.48 (95% CI 0.02 to 10.52) using a random model. There were no observed differences in antepartum haemorrhage rate, use of steroids, caesarean delivery, labour induction, or episodes of 'false labour'. Althuisius 2001b reported higher birth weights in the cerclage arm compared with the control arm (3083g versus 2224g, weighted mean difference 859, 95% CI 287 to 1430). There was heterogeneity between the studies in terms of maternal infection, delivery less than 34 weeks and so mean gestational age, which could be due to the different selection criterion and management policies employed.

No studies assessed the psychological effects on the woman or her family of being subjected to a cervical stitch, whether in the short or long term, nor the associated interventions e.g. bed rest, caesarean section.

Discussion

We found no conclusive evidence from included randomised studies that inserting a cervical stitch in women perceived to be at risk of preterm birth or second trimester pregnancy loss attributed to cervical factors, reduces the risk of pregnancy loss, preterm delivery or morbidity associated with preterm delivery. The largest included study (MRC/RCOG 1993) reported a significant reduction in the preterm deliveries before 33 weeks gestation from 18.5% in the control group to 13.8% when cervical suture was inserted. Unfortunately, the other three studies used different definitions of very preterm labour (less than 32 weeks) so the results from the MRC study could not be corroborated in different settings. It is important to note that reduced incidence of preterm deliveries in the MRC study did not result in obvious benefit for the babies.

As far as maternal side effects are concerned, cervical cerclage is consistently associated with increased risk of maternal infection/pyrexia. Although undesirable and inconvenient, there is no evidence that maternal infection/pyrexia attributed to cervical cerclage causes long‐term harm for mother or baby. The data on other maternal morbidity and increased use of tocolysis also point to a possible increase in uterine irritability being triggered with a cervical stitch. A fear of allowing a women to labour with a stitch thus risking further damage to the cervix might also be a contributing factor. Tocolytics, such as ritodrine, are unpleasant to take and not without side effects.

The small increase in caesarean sections is possibly due to women's pregnancies being 'medicalised' once a stitch is inserted and hence increased anxiety to expedite delivery. However, this evidence is more heterogeneous across the studies, i.e. less conclusive.

We suggest that the source of heterogeneity for these outcomes (maternal infection, preterm delivery less than 34 weeks' gestation and mean gestational age) is inconsistency in clinical definitions used or different patient populations studied. Inconsistent (vague) clinical definitions may contribute to biased ascertainment inherent in the studies where clinicians and patients are aware of the treatment received. For example, pyrexia greater than 38 degrees centigrade does not necessarily mean infection.

In describing the use of ultrasound (comparison 8) Althuisius 2001b included women before 27 weeks gestation, of which 66% had a previous preterm delivery less than 28 weeks gestation. In the trial by Rust 2001, the patients were included before 24 weeks' gestation but the number of women with a preterm birth was not given and this randomised controlled trial also included some low risk women in whom a short cervix was found incidentally. Therefore it is possible that there was a significant difference in the background risk of preterm labour between the two studies.

The data from two studies where ultrasound was used to select patients 'at risk' of preterm delivery show that the incidence of preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes was significantly reduced by stitch insertion and the overall preterm delivery rate (less than 37 weeks) was lower. However, pregnancies were not significantly prolonged between 24 and 32 weeks, which we feel is the most crucial time period associated with neonatal morbidity. It is noteworthy that in Althuisius 2001b trial, a policy of strict bed rest without cerclage in women with a poor history and short cervices resulted in a mean gestational age of 33 weeks and preterm delivery before 28 weeks' gestation of 15% (3/16). It is reassuring that cervical cerclage in this group of patients did not significantly increase the risk of major or minor maternal morbidity. However, it is unrealistic to expect that the data on less than 200 women could provide a clear picture on effectiveness and safety of cervical cerclage.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Until more data become available cervical cerclage should not be offered to women considered at low or medium risk of second trimester miscarriage or extreme preterm labour. There may be a role for cervical cerclage for women considered 'at very high risk' of second trimester miscarriage due to a cervical factor e.g. greater than two second trimester losses or progressive shortening of the cervix on ultrasound. However, predicting those women who will miscarry due to a cervical factor remains elusive and many women may be treated unnecessarily. The numbers involved in randomised studies are too few to draw firm conclusions.

Implications for research.

Due to the invasive nature of the cervical suture insertion and dubious benefit, future evaluation of effectiveness and safety should only be performed within rigorous randomised controlled trials. It is noteworthy that we found no randomised studies for six prespecified comparisons. Initial or secondary shortening of cervical length measured by ultrasound, may or might not identify high risk women who are going to miscarry and it could be that these women may warrant further study.

The use of 'emergency' or 'rescue' cerclage and transabdominal cerclage, remain poorly researched areas in a randomised manner, as is the optimum vaginal cerclage technique. There are no data pertaining to the effect on the family unit of the procedure, especially if prolonged episodes of hospitalisation and bed rest are prescribed. Similarly, there is no long‐term paediatric follow‐up described.

We suggest that the term 'prophylactic' should be used to describe stitches inserted in asymptomatic women who are at risk of a preterm birth based on previous obstetric risk factors (e.g. previous preterm deliveries less than 34 weeks in which cervical incompetence was suspected). 'Therapeutic' should be used to describe stitches inserted in asymptomatic women in whom a short cervix has been detected by ultrasound assessment or on digital vaginal examination. 'Emergency' or 'rescue' cerclage should be used to describe stitches inserted in women who have had their preterm labours (e.g. uterine contractions, progressive cervical dilatation, bulging membranes) sufficiently halted by tocolysis or other means between 15 and 28 weeks, that a cervical stitch is considered.

We would propose that the outcomes and definitions from this review be used as a 'minimum data set', with all other relevant outcomes or subgroup analyses reported in addition.

[Note: The 23 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 November 2009 | Amended | Search updated. Twenty‐two new reports added to Studies awaiting classification. Information about the update of this review added to Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 1, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 November 2003 | Amended | The authors were notified that the data entry for the MRC study for the outcome for delivery less than 37 weeks were incorrect. The correct values have been inserted and results section amended.The conclusions remain unaltered. |

Notes

This review is being updated by a new review team who plan to split the review into several new reviews based on clinical presentation of women at risk of preterm birth. Once the new reviews, following the publication of new protocols, are published, this review will be withdrawn from publication.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the following researchers who provided additional unpublished information: Dr Sietske M Althuisius and Dr Orion A Rust.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal infection | 3 | 1083 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.57 [1.42, 4.64] |

| 2 Induction of labour | 4 | 2061 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.92, 1.38] |

| 3 Use of tocolytics | 4 | 2059 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.14, 1.46] |

| 4 Episodes of 'false labour' | 2 | 573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.80, 1.53] |

| 5 Minor maternal morbidity | 2 | 1486 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.13, 1.55] |

| 6 Major maternal morbidity | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.08, 8.26] |

| 7 Miscarriage (pregnancy loss <24 weeks' gestation) | 3 | 1556 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.59, 1.25] |

| 8 Perinatal loss | 4 | 2059 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.48, 1.36] |

| 9 Delivery <32 weeks' gestation | 3 | 770 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.67, 2.49] |

| 10 Delivery <37 completed weeks | 4 | 2062 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.76, 1.03] |

| 11 Mean gestational age | 2 | 1486 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [‐0.35, 0.66] |

| 12 Delivery before 33 weeks' gestation (additional observation) | 1 | 1292 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.58, 0.98] |

| 13 Caesarean section (additional outcome) | 4 | 2061 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.99, 1.55] |

| 14 Steroids for neonatal pulmonary maturity | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.07, 5.79] |

| 15 Preterm prelabour ruptured membranes | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.08, 1.28] |

| 16 Antepartum haemorrhage | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.16, 3.64] |

| 17 Mean neonatal birthweight (grams) | 1 | 69 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 91.0 [‐358.28, 540.28] |

| 18 Delivery <28 weeks' gestation | 2 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.45, 2.58] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 1 Maternal infection.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 2 Induction of labour.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 3 Use of tocolytics.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 4 Episodes of 'false labour'.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 5 Minor maternal morbidity.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 6 Major maternal morbidity.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 7 Miscarriage (pregnancy loss <24 weeks' gestation).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 8 Perinatal loss.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 9 Delivery <32 weeks' gestation.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 10 Delivery <37 completed weeks.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 11 Mean gestational age.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 12 Delivery before 33 weeks' gestation (additional observation).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 13 Caesarean section (additional outcome).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 14 Steroids for neonatal pulmonary maturity.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 15 Preterm prelabour ruptured membranes.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 16 Antepartum haemorrhage.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 17 Mean neonatal birthweight (grams).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Elective cerclage versus no cerclage or bed rest, Outcome 18 Delivery <28 weeks' gestation.

Comparison 8. Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal infection | 2 | 148 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.39, 1.56] |

| 2 Delivery before 34 weeks' gestation | 2 | 148 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.44, 1.12] |

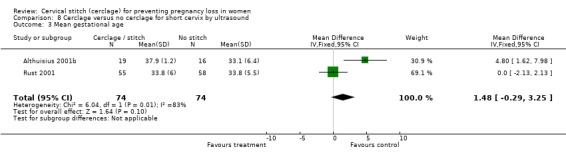

| 3 Mean gestational age | 2 | 148 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [‐0.29, 3.25] |

| 4 Perinatal loss | 2 | 148 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.36, 2.27] |

| 5 Delivery <28 weeks' gestation | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.01, 2.19] |

| 6 Use of tocolytics | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Delivery <37 completed weeks | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.13, 0.87] |

| 8 Mean neonatal birthweight (grams) | 1 | 35 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 859.0 [287.08, 1430.92] |

| 9 Miscarriage (pregnancy loss <24 weeks' gestation) | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.01, 3.30] |

| 10 Minor maternal morbidity | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

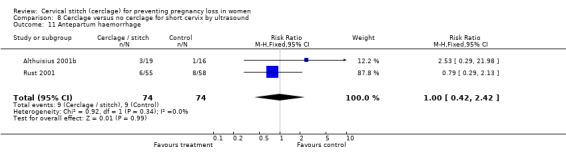

| 11 Antepartum haemorrhage | 2 | 148 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.42, 2.42] |

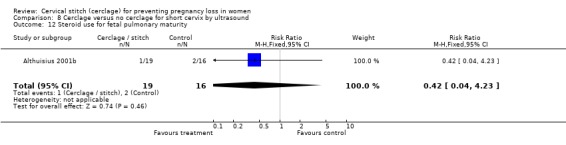

| 12 Steroid use for fetal pulmonary maturity | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.04, 4.23] |

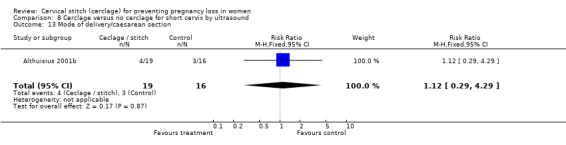

| 13 Mode of delivery/caesarean section | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.29, 4.29] |

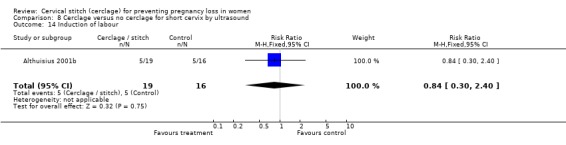

| 14 Induction of labour | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.30, 2.40] |

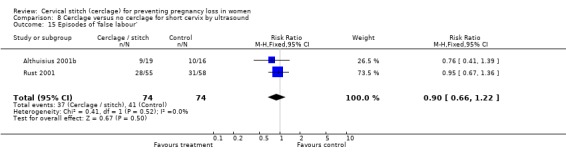

| 15 Episodes of 'false labour' | 2 | 148 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.66, 1.22] |

| 16 Preterm prelabour ruptured membranes | 1 | 35 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [0.00, 0.50] |

| 17 Pregnancy prolonged (days) | 1 | 35 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 30.00 [9.06, 50.94] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 1 Maternal infection.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 2 Delivery before 34 weeks' gestation.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 3 Mean gestational age.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 4 Perinatal loss.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 5 Delivery <28 weeks' gestation.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 6 Use of tocolytics.

8.7. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 7 Delivery <37 completed weeks.

8.8. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 8 Mean neonatal birthweight (grams).

8.9. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 9 Miscarriage (pregnancy loss <24 weeks' gestation).

8.10. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 10 Minor maternal morbidity.

8.11. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 11 Antepartum haemorrhage.

8.12. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 12 Steroid use for fetal pulmonary maturity.

8.13. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 13 Mode of delivery/caesarean section.

8.14. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 14 Induction of labour.

8.15. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 15 Episodes of 'false labour'.

8.16. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 16 Preterm prelabour ruptured membranes.

8.17. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cerclage versus no cerclage for short cervix by ultrasound, Outcome 17 Pregnancy prolonged (days).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Althuisius 2001a.

| Methods | Netherlands. Randomisation: balanced blocks assigned by telephone. | |

| Participants | 70 women deemed at risk of preterm labour by history were recruited. | |

| Interventions | Initial prophylactic cervical stitch versus no stitch if at risk by history. McDonald technique with braided polyester thread. | |

| Outcomes | Preterm delivery <34 weeks' gestation. Compound neonatal morbidity. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Althuisius 2001b.

| Methods | Netherlands. Randomisation: balanced blocks assigned by telephone. 5 year randomised trial of therapeutic cerclage plus bed rest versus bed rest. 2 women lost to follow up. | |

| Participants | 35 women who developed short cervix by ultrasound who initially were randomised to "no stitch" in the prophylactic cerclage study. | |

| Interventions | Secondary randomisation to therapeutic stitch or no stitch if cervical length <25mm <27 weeks' gestation. McDonald technique with braided polyester thread. All women who had secondary randomisation (short cervix) received bed rest. | |

| Outcomes | Preterm delivery <34 weeks gestation. Compound neonatal morbidity. | |

| Notes | Risk assessed by history, with ultrasound surveillance, therapeutic cerclage if cervical length <25mm, <27 weeks. Pooled data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lazar 1984.

| Methods | France. Randomised by pre‐prepared envelopes. 4 units used scoring chart for diagnosis in cervical incompetence. Policy of intention to treat or withhold cerclage. Pre‐agreed to analyse data after first 500 women and analyse with Mandel Hantzel method to estimate summary relative risk. No women lost to follow up. | |

| Participants | 506 women at moderate risk based on score ‐ recalculated at each visit. Women deemed high risk or low risk were excluded. Inclusion: previous pregnancy live 29‐36 weeks. Late miscarriage 14‐28 weeks. Term birth after treated preterm labour with bed rest or cervical stitch. 2 or more of above. Exclusion: previous late miscarriage of live fetus. Cervix torn up to lateral fornix and cervical os open. Uterine isthmus >1cm at hysterosalpingogram. Multiple pregnancy. Mean parity 1.78. | |

| Interventions | Elective cervical stitch versus no stitch. McDonald technique with nylon. | |

| Outcomes | Hospital admission, uterine pain, tocolytics, mode of delivery, duration of pregnancy. | |

| Notes | Intention to treat. Multiple pregnancies excluded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

MRC/RCOG 1993.

| Methods | UK/international multicentre. Randomised by telephone or post in balanced blocks. 4 randomisation centres. 7 year randomised trial. Of 1292 recruited, 26 women lost to follow up. | |

| Participants | 1292 women deemed at risk of preterm delivery in whom doctors uncertain of the diagnosis of cervical incompetence. 72% had previous preterm deliveries or second trimester miscarriages. | |

| Interventions | Cervical stitch versus no stitch unless considered clearly indicated. Stitch technique not pre‐specified. 80% McDonald and 74% used mersilene. | |

| Outcomes | Delivery before 33 completed weeks, preterm delivery and vital status of the baby. | |

| Notes | Includes multiple pregnancies. Intention to treat. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Rush 1984.

| Methods | South Africa. Randomised by random, sealed envelopes. 3 year randomised trial 194 women, 1 protocol deviation from each group. No women lost to follow up. | |

| Participants | 194 women deemed at high risk who were attending the miscarriage clinic of a teaching hospital. 8 women recruited had therapeutic stitch. 37% had previous preterm deliveries. | |

| Interventions | Elective cervical stitch versus no stitch. McDonald technique with monofilament nylon. | |

| Outcomes | Whether prophylactic cervical stitch in women deemed high risk by previous history prolongs gestation. | |

| Notes | McDonald technique with monofilament nylon. Analysis to allocation rather than to treat. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Rust 2001.

| Methods | USA. Randomised by computer generated random sequence. 1 year randomised trial. No women lost to follow up. | |

| Participants | 113 women at risk of preterm birth by history underwent transvaginal ultrasound assessment. Any low risk women who had ultrasound evaluation were also assessed for abnormality of the lower uterine segment. Women were excluded if membranes were prolapsed below the external os, lethal fetal or chromosomal anomaly, abruption or unexplained vaginal bleeding, uterine activity and cervical change associated with preterm labour. 45% had previous preterm deliveries. | |

| Interventions | Elective cervical stitch versus no stitch. McDonald technique. | |

| Outcomes | Assess benefits of vaginal cerclage in women with preterm dilatation of the internal os by second trimester ultrasound. Assess by depth of membrane prolapse >25% of total length and reduction in distal length to <25mm. | |

| Notes | Included multiple pregnancies. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Caspi 1990 | Quasi randomised (hospital chart number). |

| Forster 1986 | Quasi randomised (initial letter of surname). |

| Szeverenyi 1992 | Hungarian paper. Author contacted for English version ‐ no reply. English co‐authors contacted ‐ feel some women included in MRC/RCOG trial. |

| Varma 1989 | Written to author and head of department twice. No response. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Nicolaides 2001.

| Trial name or title | RCT of cervical cerclage in women with short cervix by routine ultrasound at 23 weeks. |

| Methods | |

| Participants | 5000 women |

| Interventions | Prophylactic cervical stitch in women with cervical length <15mm. |

| Outcomes | Preterm delivery <32 weeks' gestation. |

| Starting date | 01/12/1998 |

| Contact information | Prof Nicolaides, Kings College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London. |

| Notes | Trial stopped. Analysis awaited. |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Contributions of authors

Andrew Drakeley developed the idea and drafted the review. Devender Roberts and Zarko Alfirevic assisted with the review. Andrew Drakeley and Devender Roberts completed data forms independently. Andrew Drakeley entered the data. Devender Roberts double checked data entry. Zarko Alfirevic reviewed the analysis.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Althuisius 2001a {published data only}

- Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Geijn HP, Bekedam DJ, Hummel P. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (CIPRACT): study design and preliminary results. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:823‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Althuisius 2001b {published data only}

- Althuisius S, Dekker G, Hummel P, Bekedam D, Geijn H. CIPRACT (cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial): final results [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;184(1):S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althuisius S, Dekker G, van‐Geijn H, Bekedam D, Hummel P. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial, preliminary results. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182(1 Pt 2):S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, Bekedam DJ, Geijn HP. Final results of the cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (CIPRACT): therapeutic cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;185:1106‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Geijn HP, Bekedam DJ, Hummel P. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (CIPRACT): study design and preliminary results. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:823‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lazar 1984 {published data only}

- Lazar P, Gueguen S. Multicentred controlled trial of cervical cerclage in women at moderate risk of preterm delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1984;91:731‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MRC/RCOG 1993 {published data only}

- Anonymous. Interim report of the medical research council/royal college of obstetricians and gynaecologists multicentre randomized trial of cervical cerclage. Mrc/rcog working party on cervical cerclage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1988;95(5):437‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. MRC/RCOG randomised trial of cervical cerclage. Proceedings of 23rd British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 1983 July 12‐15; Birmingham, UK. 1983:187.

- Anonymous. MRC/RCOG randomised trial of cervical cerclage. Proceedings of the 24th British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 1986 April 15‐18; Cardiff, UK. 1986:268.

- MRC/RCOG Working Party on Cervical Cerclage. Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicentre randomised trial of cervical cerclage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1993;100:516‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rush 1984 {published data only}

- Rush R, Isaacs S. Prophylactic cervical cerclage and gestational age at delivery. Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Priorities in Perinatal Care; 1983; South Africa. 1983:132‐7.

- Rush RW, Isaacs S, McPherson K, Jones L, Chalmers I, Grant A. A randomized controlled trial of cervical cerclage in women at high risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1984;91:724‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rust 2001 {published data only}

- Rust O, Atlas R, Jones K, Benham B, Balducci J. A randomized trial of cerclage vs no cerclage in patients with sonographically detected 2nd trimester premature dilation of the internal os. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182(1 Pt 2):Ss13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust O, Atlas R, Reed J, Gaalen J, Balducci J. Regression analysis of perinatal morbidity for second‐trimester sonographic evidence of internal os dilation and shortening of the distal cervix [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;184(1):S26. [Google Scholar]

- Rust O, Atlas R, Wells M, Kimmel S. Does cerclage location influence perinatal outcome [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;185(6 Suppl):S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust O, Atlas R, Wells M, Kimmel S. Second trimester dilatation of the internal os and a history of prior preterm birth [abstract]. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002;99(4 Suppl):14S. [Google Scholar]

- Rust O, Atlas R, Wells M, Rawlinson K. Cerclage in multiple gestation with midtrimester dilatation of the internal os [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;185(6 Suppl):S111. [Google Scholar]

- Rust OA, Atlas RO, Jones KJ, Benham BN, Balducci J. A randomized trial of cerclage versus no cerclage among patients with ultrasonographically detected second trimester preterm dilatation of the internal os. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:830‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust OA, Atlas RO, Reed J, Gaalen J, Balducci J. Revisiting the short cervix detected by transvaginal ultrasound in the second trimester: why cerclage therapy may not help. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;185:1098‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Caspi 1990 {published data only}

- Caspi E, Schneider DF, Mor Z, Langer R, Weinraub Z, Bukovsky I. Cervical internal os cerclage: description of a new technique and comparison with shirodkar operation. American Journal of Perinatology 1990;7(4):347‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forster 1986 {published data only}

- Forster F, During R, Schwarzlos G. Treatment of cervical incompetence‐ cerclage or supportive therapy [Therapie der Zervixinsuffizienz‐ Zerklage oder Stutzpessar]. Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie 1986;108:230‐37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Szeverenyi 1992 {published data only}

- Lampe L. Effectiveness of cervical cerclage before pregnancy. Personal communication 1988.

- Szeverenyi M, Chalmers I, Grant AM, Nagy T, Nagy J, Balogh I, et al. Operative treatment of the cervical incompetency during the pregnancy: judgement of the competence of cerclage operation. Orvosi Hetilap 1992;133:1823‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Varma 1989 {published data only}

- Varma TR. To assess further the value of cervical cerclage in pregnancy. Personal communication 1989.

References to studies awaiting assessment

Althuisius 2002 {published data only}

- Althuisius S, Dekker G, Hummel P, Bedekam D, Kuik D, Geijn H. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (cipract): effect of therapeutic cerclage with bed rest vs. bed rest only on cervical length. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002;20(2):163‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althuisius S, Dekker G, Hummel P, Geijn H. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (cipract): emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002;187(6 Pt 2):S86. [Google Scholar]

Althuisius 2003 {published data only}

- Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, Geijn HPV. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;189:907‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beigi 2005 {published data only}

- Beigi A, Zarrinkoub F. Elective versus ultrasound‐indicated cervical cerclage in women at risk for cervical incompetence. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran 2005;19(2):103‐7. [Google Scholar]

Berghella 2003 {published data only}

- Berghella V, Odibo A, Tolosa J. Cerclage for prevention of preterm birth with a short cervix on transvaginal ultrasound: a randomized trial [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;189(6 Suppl 1):S167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berghella 2004 {published data only}

- Berghella V, Odibo AO, Tolosa JE. Cerclage for prevention of preterm birth in women with a short cervix found on transvaginal ultrasound examination: a randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;191:1311‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blair 2002 {published data only}

- Blair O, Fletcher H, Kulkarni S. A randomised controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient cervical cerclage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2002;22(5):493‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bowes 2003 {published data only}

- Bowes WA. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial (CIPRACT): effect of therapeutic cerclage with bed rest vs. bed rest only on cervical length. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 2003;58(2):88‐9. [Google Scholar]

Dor 1982 {published data only}

- Dor J, Shalev J, Mashiach S, Blankstein J, Serr DM. Elective cervical suture of twin pregnancies diagnosed ultrasonographically in the first trimester following induced ovulation. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 1982;13:55‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ezechi 2004 {published data only}

- Ezechi OC, Kalu BKE, Nwokoro CA. Prophylactic cerclage for the prevention of preterm delivery. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2004;85:283‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Figueroa 2008 {published data only}

- Figueroa D, Mancuso M, Maddox Paden M, Szychowski J, Owen J. Does mid‐trimester nugent score or vaginal pH predict gestational age at delivery in women at risk for preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;199(6 Suppl 1):S215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kassanos 2001 {published data only}

- Kassanos D, Salamalekis E, Vitoratos N, Panayotopoulos N, Loghis C, Creatsas C. The value of transvaginal ultrasonography in diagnosis and management of cervical incompetence. Clinical & Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology 2001;28:266‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Keeler 2009 {published data only}

- Keeler SM, Kiefer D, Rochon M, Quinones JN, Novetsky AP, Rust O. A randomized trial of cerclage vs. 17 alpha‐hydroxyprogesterone caproate for treatment of short cervix. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2009;37(5):473‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Owen 2004 {published data only}

- Owen J. Surgical procedure to prevent premature birth (ongoing). ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (accessed 15 September 2004) 2004.

Owen 2008 {published data only}

- Owen J. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high‐risk women with shortened mid‐trimester cervical length. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;199(6 Suppl 1):S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Owen 2009 {published data only}

- Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, Berghella V, Sheffield JS, Perez‐Delboy A, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high‐risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;201(4):375.e1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rust 2006 {published data only}

- Rust O, Larkin R, Roberts W, Quinones J, Rochon M, Reed J, et al. A randomized trial of cerclage versus 17‐hydroxyprogesterone (17p) for the treatment of short cervix [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;195(6 Suppl 1):S112. [Google Scholar]

Secher 2007 {published data only}

- Secher NJ, McCormack CD, Weber T, Hein M, Helmig RB. Cervical occlusion in women with cervical insufficiency: protocol for a randomised, controlled trial with cerclage, with and without cervical occlusion. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2007;114(5):649‐e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Silver 2005 {published data only}

- Silver R. Vaginal ultrasound cerclage trial (ongoing). Evanston Northwestern Healthcare (www.enh.org) (accessed 14 June 2005) 2005.

Szychowski 2009 {published data only}

- Szychowski JM, Owen J, Hankins G, Iams J, Sheffield J, Perez‐Delboy A, et al. Timing of mid‐trimester cervical length shortening in high‐risk women. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2009;33(1):70‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

To 2004 {published data only}

- To MS, Alfirevic Z, Heath VCF, Cicero S, Cacho AM, Williamson PR, et al. Cervical cerclage for prevention of preterm delivery in women with short cervix: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1849‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tsai 2009 {published data only}

- Tsai YL, Lin YH, Chong KM, Huang LW, Hwang JL, Seow KM. Effectiveness of double cervical cerclage in women with at least one previous pregnancy loss in the second trimester: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2009;35(4):666‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Nicolaides 2001 {unpublished data only}

- Nicolaides K. Randomised controlled trial of cervical cerclage in women with a short cervix identified by routine sonography at 23 weeks of pregnancy. mRCT: metaRegister of Controlled Trials. http://www.controlled‐trials.com (accessed July 2001).

- Nicolaides K. Randomised controlled trial of cervical cerclage in women with twin pregnancies found to have an asymptomatic short cervix. mRCT: metaRegister of Controlled Trials. http://www.controlled‐trials.com (accessed July 2001).

Additional references

Anthony 1997

- Anthony GS, Walker RG, Cameron AD, Price JL, Walker JJ, Calder AA, et al. Trans‐abdominal cervico‐isthmic cerclage in the management of cervical incompetence. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 1997;72:127‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berry 1995

- Berry CW, Brambati B, Eskes TKAB, Exalto N, Fox H, Geraedts JPM, et al. The Euro‐Team Early Pregnancy (ETEP) protocol for recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction 1995;10(6):1516‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chanrachakul 1998

- Chanrachakul B, Herabutya Y. Emergency cervical cerclage: Ramathibodi Hospital Experience. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 1998;1(11):858‐61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Drakeley 1998

- Drakeley AJ, Quenby S, Farquharson RG. Mid trimester loss ‐ appraisal of a screening protocol. Human Reproduction 1998;13(7):1975‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibb 1995

- Gibb DMF, Salaria DA. Transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage in the management of recurrent second trimester miscarriage and pre‐term delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;102:802‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grant 1989

- Grant A. Cervical cerclage to prolong pregnancy. In: Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC editor(s). Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989:633‐46. [Google Scholar]

McDonald 1957

- McDonald IA. Suture of the cervix for inevitable miscarriage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1957;64:346‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDonald 1980

- McDonald IA. Cervical Cerclage. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 1980;7:461‐79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murakawa 1993

- Murakawa H, Utumi T, Hasegawa I, Tanaka K, Fuzimori R. Evaluation of threatened preterm delivery by transvaginal ultrasonographic measurement of cervical length. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;82:829‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.1 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Riverius 1658

- Riverius L, Culpeper N, Cole A. On Barrenness, in the practice of Physick. London: Peter Cole, 1658. [Google Scholar]

Rust 2000a

- Rust OA, Atlas RO, Jones KJ, Benham BN, Balducci J. A randomised trial of cerclage versus no cerclage among patients with ultrasonographically detected second trimester preterm dilatation of the internal os. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:830‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shirodkar 1955

- Shirodkar VN. A new method of operative treatment for habitual abortions in the second trimester of pregnancy. Antiseptic 1955;52:299‐300. [Google Scholar]

Stirrat 1999

- Stirrat G, Wardle PG. Recurrent miscarriage. In: James DK, Steer PJ, Weiner CP, Gonik B editor(s). High Risk Pregnancy. 2nd Edition. WB Saunders Press, 1999:99. [Google Scholar]

Wong 1993

- Wong GP, Farquharson DF, Dansereau J. Emergency cerclage: a retrospective review of 51 cases. American Journal of Perinatology 1993;10(5):341‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Grant 1995a

- Grant AM. Cervical cerclage (all trials). [ revised 11 April 1994]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.

Grant 1995b

- Grant AM. Cervical cerclage for high risk of early delivery. [revised 11 April 1994]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.

Grant 1995c

- Grant AM. Cervical cerclage for moderate risk of early delivery. [revised 11 April 1994]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.

Grant 1995d

- Grant AM. Cervical cerclage in twin pregnancy. [revised 11 April 1994]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.

Grant 1995e

- Grant AM. Stutz pessary vs cervical cerclage. [ revised 11 April 1994]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.