Abstract

Background

It is suggested that oestrogen may promote changes in cervical favourability with minimal effect on uterine activity and could be used to induce labour or prime the cervix. A variety of oestrogen preparations (infusions, gels, creams and tablets) and routes of administrations (oral, vaginal, extra‐amniotic) vaginal,extra‐amniotic) have been used in inpatient and outpatient settings. Oestrogen is rarely used in clinical practice. There are no commercially available preparations of oestrogen for induction and in most cases this is prepared specifically for the study.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of oestrogens alone, or with amniotomy, for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour in comparison with other methods of induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register (January 2008), the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2007), and bibliographies of relevant papers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing oestrogens for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed by at least two review authors.

Main results

Seven studies (465 women) were included. Only studies using oestrogens alone were identified; there were no trials of oestrogen with amniotomy. Three studies used intravaginal oestrogen, two used extra‐amniotic oestrogen, one used an intravenous preparation, and one used oral tablets. Three studies were inpatient studies, one was an outpatient intervention and three did not state whether the setting was inpatient or outpatient. None of the studies reported the primary outcomes of rates of vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours. There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2), oxytocin alone, or extra amniotic PGF2a, as to whether oestrogen is effective in inducing labour.

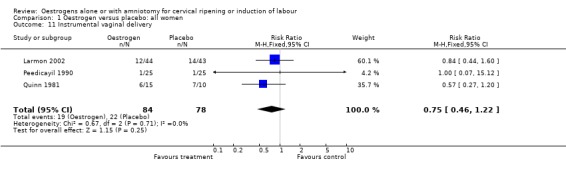

There was no evidence of a difference between oestrogen and placebo in the rate of caesarean section, uterine hyperstimulation with or without fetal heart rate changes, or instrumental vaginal delivery.

Authors' conclusions

There were insufficient data to quantify the safety and effectiveness of oestrogen as an induction agent; they should only be used as part of randomised control trials as there are alternative effective options for inducting labour.

Plain language summary

Oestrogens alone or with amniotomy for cervical ripening or induction of labour

There is not enough evidence, from randomised controlled trials, to show the effects and safety of oestrogen to ripen the cervix and help bring on labour.

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially, because of safety concerns for either the pregnant woman or baby. Oestrogen is a hormone involved in the ripening of the neck of the womb (cervix) and preparing it for the birth of the baby. It is possible that oestrogen increases the release of other local hormones (prostaglandins) which help ripen the cervix. A variety of oestrogen preparations have been used (such as tablets, creams and infusions). They have been used for inductions when women are inpatients and outpatients. There is not enough research from the review of seven studies (with 465 women) to show the true effect of oestrogen. Oestrogen is not commonly used in current clinical practice as alternative agents that are known to be effective are available.

Background

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

Studies in sheep showed that there is a pre‐labour rise in oestrogen and a decrease in progesterone, both of these changes stimulate prostaglandin production and may help initiate labour. Research in humans has failed to demonstrate a similar physiological mechanism. However oestrogen has been suggested as an effective cervical ripening and induction agent, promoting changes in cervical favourability but with less effect on uterine activity and as such could be used to induce labour, or prime the cervix and uterus, prior to induction with other methods. There has been a slight resurgence of interest in oestrogens as an agent for cervical ripening in an outpatient setting, and induction of labour in outpatient versus inpatient settings are the subject of another review (Kelly 2008). Most studies have used natural oestrogen analogues such as oestradiol. More potent synthetic oestrogens such as stilbestrol are no longer used because of the long term adverse events in female children. Oestrogens are associated with a variety of adverse effects (such as an increase in thromboembolic disease) which could reduce the potential benefit of their use in pregnancy. A variety of oestrogen preparations (including tablets, infusions, gels and creams) and routes of administrations have been used (oral, rectal, vaginal, intracervical, extra‐amniotic and intravenous routes). Administration of some oestrogen preparations such as tablets gels or creams will be possible in either an inpatient or outpatient setting. However, using intravenous or extraamniotic infusions are likely to only be possible in an inpatient setting. In most studies the oestrogen was prepared specifically for the study. The use of oestrogen as an induction agent is not currently in common use in clinical practice and there are no commercially available preparations of oestrogen for its use in cervical ripening or induction of labour .

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of oestrogens alone, or with amniotomy, for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour in comparison with other methods of induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing oestrogens alone or with amniotomy for cervical ripening or labour induction, with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see 'Data collection and analysis'); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the prestated outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a single live fetus. Women having induction of labour in either inpatient or outpatient settings will be included.

Predefined sub‐group analyses will be (see Data collection and analysis): previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data will appear in the analysis tables.

Types of interventions

There are a variety of oestrogen preparations (tablets, infusions, gels and creams) and several possible routes of administrations have been used (oral, rectal, vaginal, intracervical, extra‐amniotic and intravenous routes). We will include any oestrogen used alone or with amniotomy compared with any of the 14 interventions listed above oestrogen in the generic protocol (namely: 1. placebo/no treatment; 2. vaginal prostaglandins; 3. intracervical prostaglandins; 4.intravenous oxytocin; 5.amniotomy; 6.intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy; 7. vaginal misoprostol; 8.oral misoprostol; 9.mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter; 10.membrane sweeping; 11.extra‐amniotic prostaglandins; 12.intravenous prostaglandins; 13.oral prostaglandins; and 14 mifepristone).

As a number of trials administer oestrogen via a Foley catheter into the extra amniotic space, it was decided by the authors prior to data extraction to exclude any trial where the Foley catheter balloon was inflated to any volume greater than or equal to 10 mls. At this level it was felt that there was potential for the catheter balloon to have an additional effect to the oestrogens, and that this interaction would make it difficult to measure the effect of oestrogens.

For oestrogen and amniotomy to be considered as concomitant interventions both needed to be delivered within two hours of each other. This is in accordance with other reviews on induction of labour where amniotomy is considered as a concomitant intervention. Studies of oestrogen and amniotomy with other interventions are considered separate comparisons.

It is possible to use some oestrogen preparations (such as tablets, gels or creams) by oral or vaginal route in either inpatient or outpatient settings. However, using intravenous or extraamniotic infusion are likely to only be possible in an inpatient setting.

The primary comparisons listed below are the only comparisons for which there are data. Comparisons for which no studies were identified (namely oestrogens with amniotomy and comparison with vaginal misoprostol; oral misoprostol; mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter; membrane sweeping; intravenous prostaglandins; oral prostaglandins; and mifepristone) are not listed below.

Primary comparisons. (1) oestrogen alone (all routes) versus placebo (all routes); (2) oestrogen alone (all routes) versus vaginal prostaglandin; (3) oestrogen alone (all routes) versus intracervical prostaglandin; (4) oestrogen alone (all routes) versus oxytocin alone; (5) oestrogen alone (all routes) versus extra‐amniotic prostaglandins.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Sub‐group analyses will be limited to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction:

Measures of effectiveness: (6) cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications: (8) uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium stained liquor; (13) Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects (e.g. thromboembolic events); (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction: (26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The aim of treatment maybe either cervical ripening and/or induction of labour. Where the aim of treatment is cervical ripening for example in an outpatient setting rather than induction of labour, then the other primary outcomes rather than "vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours" are more relevant.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the review we used the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (> 5 contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short term variability).

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (January 2008).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's trials register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from: 1. quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); 2. monthly searches of MEDLINE; 3. handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences; 4. weekly current awareness search of a further 37 journals.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the 'Search strategies for identification of studies' section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are given a code (or codes) depending on the topic. The codes are linked to review topics. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using these codes rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

The initial search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

The reference lists of trial reports and reviews were searched by hand.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy has been developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, examining the effects of these methods when induction of labour was undertaken in a variety of clinical groups e.g. restricted to primiparous women or those with ruptured membranes. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged according to the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The data was then extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods have been listed in a specific order, from one to 23. Each primary review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 23) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) will include only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2003); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin (Kelly 2001); (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2003); (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Boulvain 2001); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Neilson 2000); (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001a); (18) hyaluronidase Kavanagh 2006a; (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema (Kelly 2001b); (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004);

(25) nitric oxide (Kelly 2008a); (26) hypnosis.

The primary reviews will be analysed by the following subgroups: (1) previous caesarean section or not; (2) nulliparity or multiparity; (3) membranes intact or ruptured; (4) cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

The secondary reviews will include all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews, and will include only five primary outcome measures. There will thus be six secondary reviews, of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

(1) nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (2) nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (3) multiparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (4) multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (5) previous caesarean section (intact or ruptured membranes and unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined). (6) previous caesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which include data which have changed, will also be updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was coordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with The Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data were extracted to a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous reviewers in the area of induction of labour.

Information was extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process was completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examined the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These were then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Table 22 for the purpose of the reviews.

1. Methodological quality of trials.

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence | Computer generated sequence, random number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation | Central randomisation, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Performance bias was examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials i.e. participant, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels was sought.

Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they meet the pre stated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Cochrane 2008). Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention to treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis is performed if possible). Where data were missing, clarification was sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data were excluded from the analysis. This decision rested with the reviewers of primary reviews and is clearly documented. If missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data were extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting was poor, methodological issues were reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data had been extracted, they were distributed to individual reviewers for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2008), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis included all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and sub‐group analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or sub‐groups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Results

Description of studies

In total, 25 studies were considered; 18 were excluded and seven (with a total of 465 women) were included. For further details of study characteristics refer to 'characteristics of included/excluded studies'.

All included studies compared oestrogen alone with other interventions, no included studies compared oestrogen with amniotomy with any other interventions.

Excluded studies:

Six studies involved complex interventions, with oestrogen or placebo being combined with an extra amniotic Foley catheter (Gordon 1977; Peedicayil 1989; Pedersen 1981; Roztocil 1998; Stewart 1981; Thiery 1979). In one study oestrogen or a placebo was then followed by oral prostaglandin E2 (Luther 1980).

Eight studies did not report any prespecified outcomes in an extractable format (Griffin 2003; Klopper 1973; Magnani 1986; Mamo 1994; Moran 1994; Palmero 1997; Pedersen 1981; Thiery 1978).

One study involved induction after failed induction (Martin 1955).

One study involved intra amniotic administration of oestrogen after the onset of labour (Klopper 1969).

One study involved induction with Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (Sasaki 1982).

Included studies:

The oestrogen preparations used varied. One study (Klopper 1962) used oral tablets, one used intravenous infusion (Pinto 1967), two used extra‐amniotic oestrogen (Peedicayil 1990, Quinn 1981) and three used intravaginal oestrogen cream (Larmon 2002, Magann 1995, Tromans 1981)

Five studies compared oestrogen with placebo. The oestrogen was delivered as oral tablets in one trial (Klopper 1962), as an intravenous infusion in another (Peedicayil 1990), as an extra‐amniotic formulation in two studies (Pinto 1967; Quinn 1981) and a vaginal oestrogen cream in one study (Larmon 2002). One study compared intravaginal oestrogen cream with intravaginal PGE2 (Tromans 1981).

One study compared intravaginal oestrogen cream with intracervical PGE2 (Larmon 2002). Different to other included studies these interventions were given as a weekly outpatient treatment until the onset of spontaneous labour.

One study compared intracervical oestrogen with intracervical PGE2 (Magann 1995).

The same study compared intracervical oestrogen with oxytocin (Magann 1995).

One study compared extra‐amniotic oestrogen with extra‐amniotic PGF2a (Quinn 1981).

Three studies had three arms and hence reported in two comparisons (Magann 1995; Larmon 2002; Quinn 1981).

Three studies (Pinto 1967; Quinn 1981,Tromans 1981 that included a total of 185 women) stated they were undertaken in an inpatient setting, the first two of these studies used extra‐amniotic formulation the third used intravaginal cream. One study using intravaginal cream in the intervention arm (Larmon 2002 with 87 women) was undertaken in an outpatient setting. Three studies did not state if the study had been conducted in an inpatient or outpatient setting, the first used oral oestradiol tablets (Klopper 1962), the second (Magann 1995) used vaginal cream, and the third (Peedicayil 1990) used extra‐amniotic oestrogen.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation and concealment

One trial used computer‐generated random number sequences (Magann 1995), one trial used random number tables (Larmon 2002), one trial allocated depending on the date of admission (Tromans 1981) and one trial used alternation as a means of allocation (Pinto 1967). The remaining studies were unclear regarding the method of generation of the randomisation sequence.

Concealment was achieved by sealed opaque envelopes in one trial (Magann 1995), opaque numbered envelopes in another (Larmon 2002) and using coded drug boxes or bottles in two further trials (Peedicayil 1990; Quinn 1981). The remaining studies were unclear regarding concealment or used open allocation as a result of inadequate randomisation methods.

Blinding

Double blinding was accomplished in all four placebo controlled trials (Klopper 1962; Peedicayil 1990; Pinto 1967; Quinn 1981), and was not possible in the remaining trials due to the nature of the active comparison.

Effects of interventions

None of the studies compared oestrogen with amniotomy. None of the studies reported the primary outcome of rates of either vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours, or the measure of effectiveness of the cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours. There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with vaginal PGE2, intracervical PGE2, oxytocin alone or extra amniotic PGF2a, as to whether oestrogen is effective for inducing labour.

All the outcomes listed under 'Types of outcome measures' and sub‐groups defined in 'Types of participants' were sought. Only those with data appear in the analysis tables. Data discussed applies to the 'all women' group and unless stated there was no difference between any of the prespecified sub‐groups.

(1) Oestrogen alone (all routes) versus placebo (all routes) (five studies: 306 women)

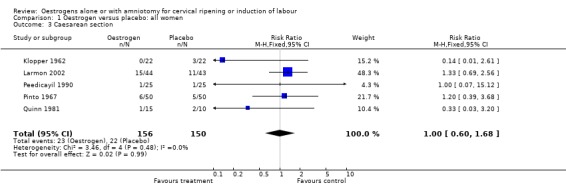

There was no evidence of a difference between the rate of caesarean section between oestrogen and placebo (14.7% versus 14.6%, relative risk (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.6 to 1.68). There was no evidence of a difference between rates of uterine hyperstimulation with or without fetal heart rate changes or instrumental vaginal delivery.

(2) Oestrogen alone (all routes) versus vaginal prostaglandin (one study: 60 women)

There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with vaginal PGE2.

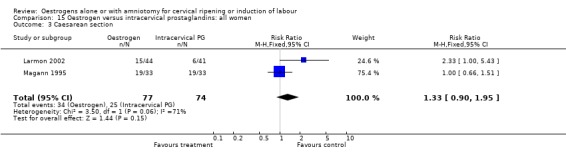

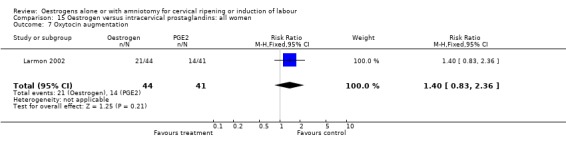

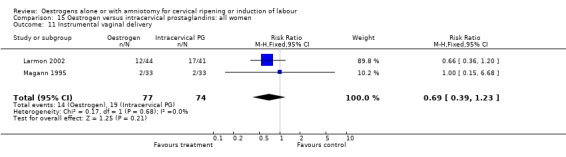

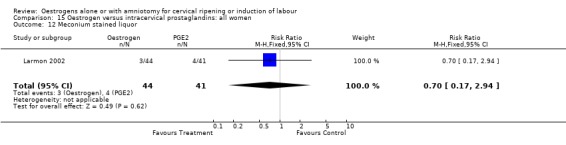

(3) Oestrogen alone (all routes) versus intracervical prostaglandin (two studies: 151 women)

There was no evidence of a difference between the rate of caesarean section between oestrogen and intracervical PGE2 (44.1% versus 33.8%, RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.95).There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with intracervical PGE2.

(4) Oestrogen alone (all routes) versus oxytocin alone (one study: 66 women)

There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with oxytocin alone.

(5) Oestrogen alone (all routes) versus extra amniotic prostaglandins (one study: 30 women)

There were insufficient data to make any meaningful conclusions when comparing oestrogen with extra amniotic PGF2a.

Discussion

There were insufficient data to draw any conclusions regarding the efficacy of oestrogen alone as an induction agent. No trails considered the use of oestrogen with amniotomy and none of the included trials reported on vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

The delivery of oestrogen within the included trials is varied (oral, intravenous, vaginal, and extra‐amniotic), and no attempt was made to sub‐divide the routes of administration. The effect of different delivery methods would not be possible to quantify unless much larger numbers of trials were available. In most studies it is specified that the oestrogen preparation was made specifically for the study and was not from a commercially available form. There is very limited information about the use of oestrogens in an outpatient setting. In this context the aim of treatment has been to promote cervical ripening rather than induce labour, and the outcome of achieving a delivery within 24 hours is not the most relevant outcome.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Oestrogens should not currently be used for induction of labour or cervical ripening as their effectiveness and safety cannot be quantified at present and there are alternative effective treatment options.

Implications for research.

Future studies evaluating the effectiveness of oestrogen need to be of good methodological quality and should report on all the outcomes listed in the generic protocol of the induction of labour reviews.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 April 2008 | New search has been performed | Four new studies were identified and evaluated for the purpose of this update (Griffin 2003; Larmon 2002; Moran 1994; Thiery 1979). One of these (Larmon 2002) is included in the review; the other three excluded: two because they did not report any of the prespecified outcomes (Griffin 2003; Moran 1994) and one (Thiery 1979) because it was a "complex intervention" ‐ the oestrogen used within the trial was combined with the use of an extra amniotic placed foley catheter. A study awaiting awaiting assessment in the previous review has now been excluded (Luther 1980), again because the trial evaluated a "complex intervention" of intramuscular oestradiol with PGE2. |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sonja Henderson, Lynn Hampson and Claire Winterbottom for their support in the production of this review. As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), one or more members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Also thanks to Zarko Alfirevic, Justus Hofmeyr and Jim Neilson.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oestrogen versus placebo: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

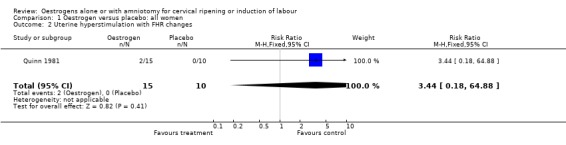

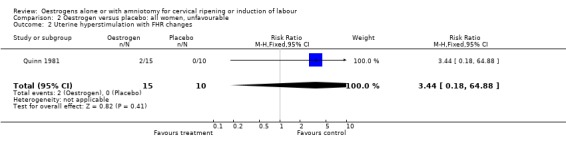

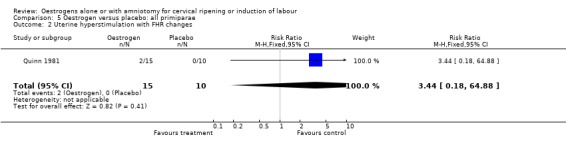

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.44 [0.18, 64.88] |

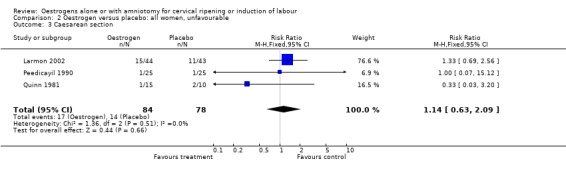

| 3 Caesarean section | 5 | 306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.60, 1.68] |

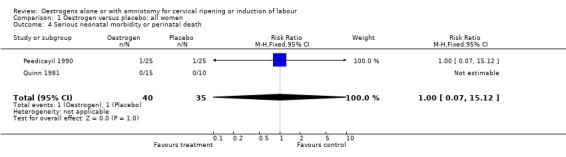

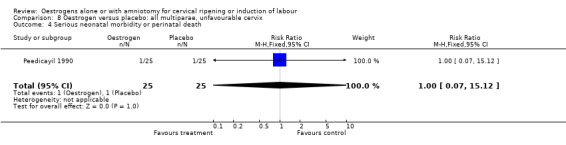

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

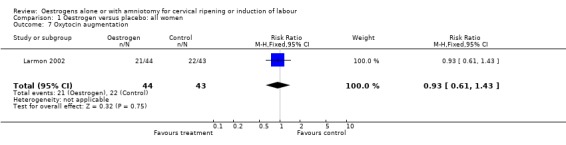

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.61, 1.43] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

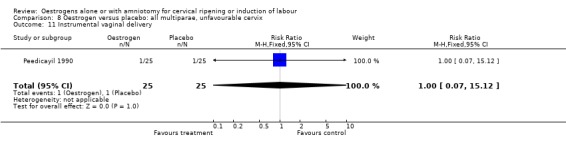

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.46, 1.22] |

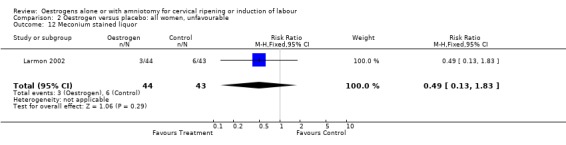

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.13, 1.83] |

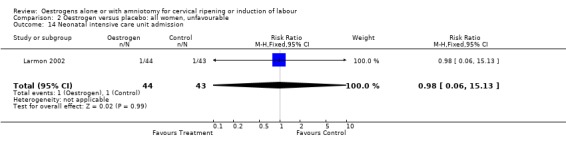

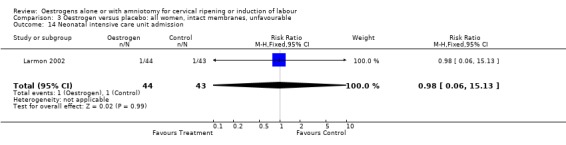

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.06, 15.13] |

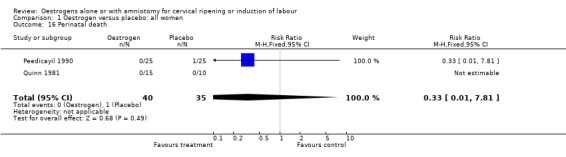

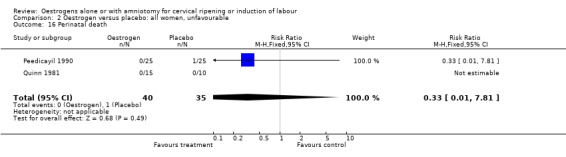

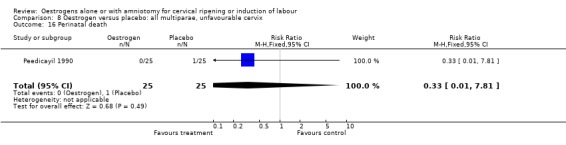

| 16 Perinatal death | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.81] |

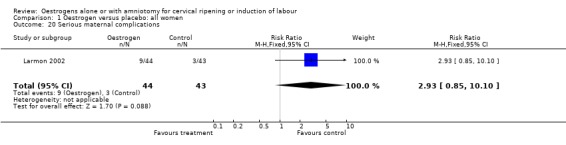

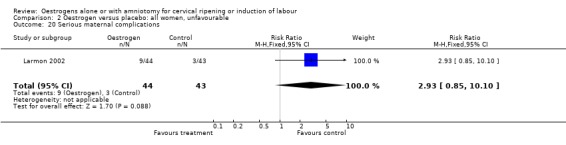

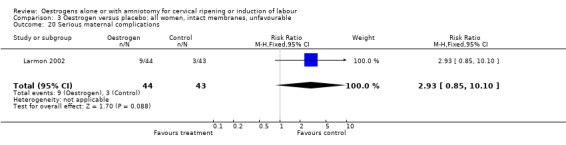

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.93 [0.85, 10.10] |

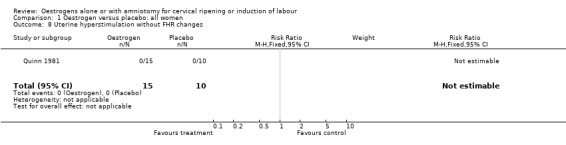

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.4. Analysis.

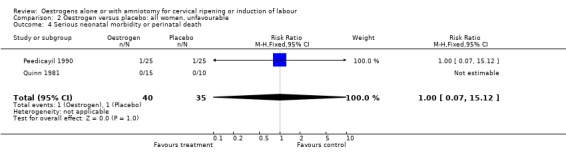

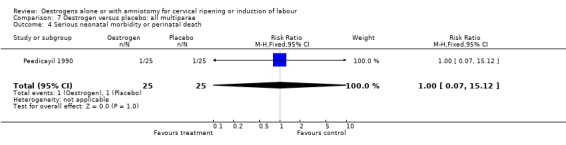

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

1.7. Analysis.

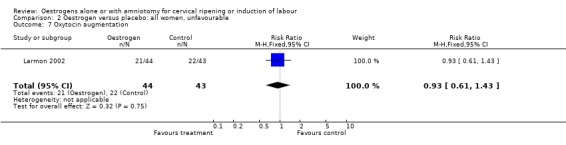

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

1.8. Analysis.

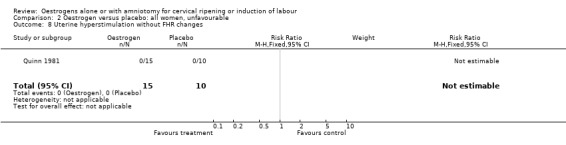

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

1.11. Analysis.

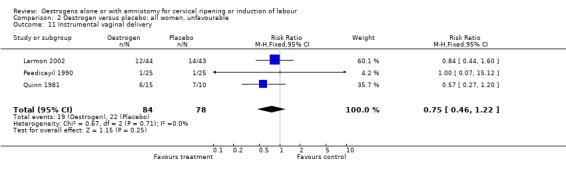

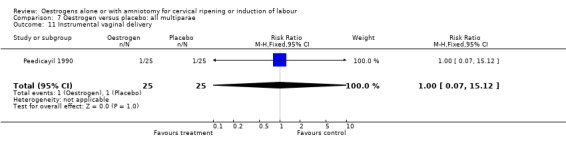

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

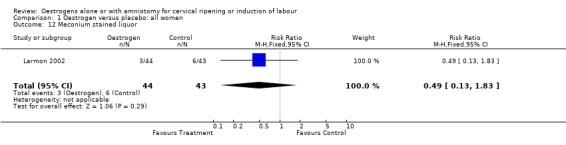

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

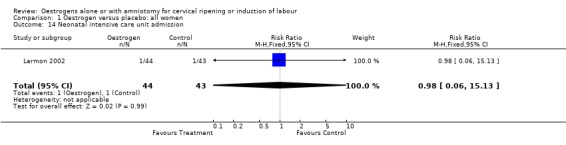

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

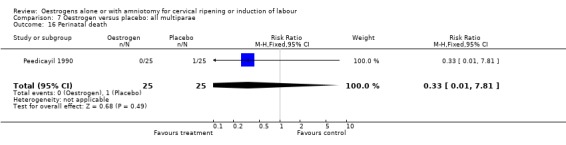

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 2. Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.44 [0.18, 64.88] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.63, 2.09] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.61, 1.43] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.46, 1.22] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.13, 1.83] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.06, 15.13] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.81] |

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.93 [0.85, 10.10] |

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

2.20. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, unfavourable, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

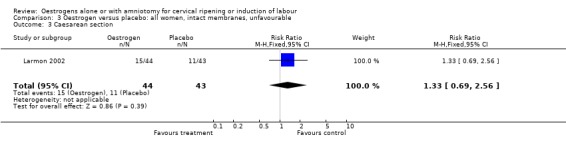

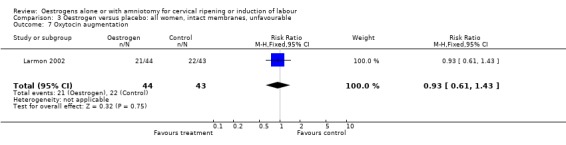

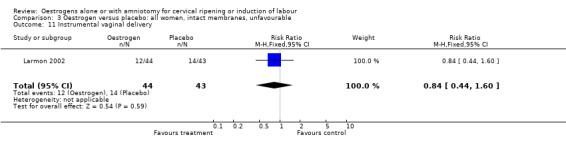

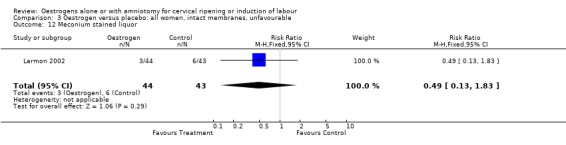

Comparison 3. Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

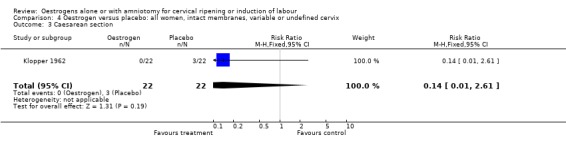

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.69, 2.56] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.61, 1.43] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.44, 1.60] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.13, 1.83] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.06, 15.13] |

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.93 [0.85, 10.10] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

3.14. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

3.20. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 4. Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

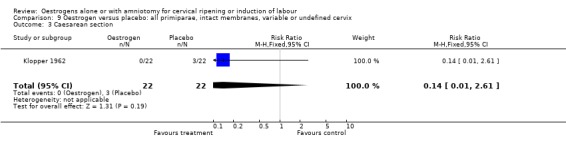

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.61] |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oestrogen versus placebo: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

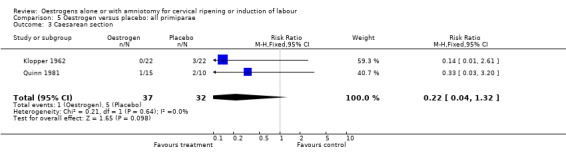

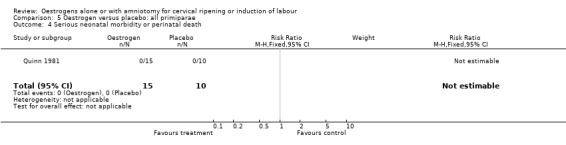

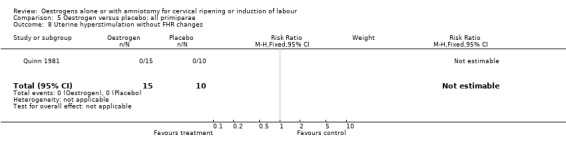

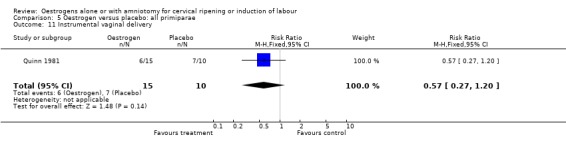

Comparison 5. Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

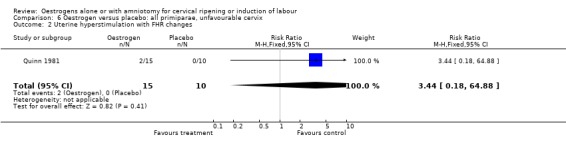

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.44 [0.18, 64.88] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.04, 1.32] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

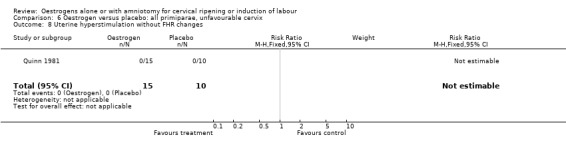

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

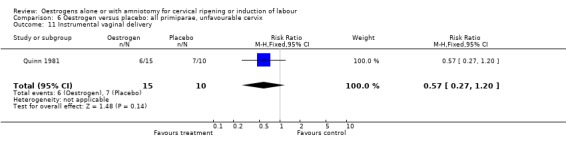

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.27, 1.20] |

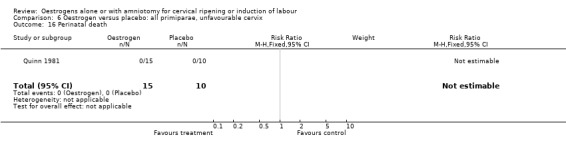

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

5.11. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

5.16. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 6. Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.44 [0.18, 64.88] |

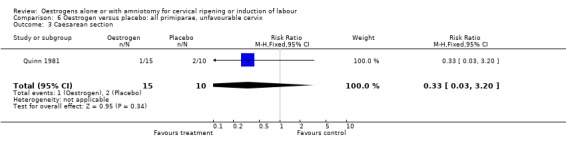

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.03, 3.20] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.27, 1.20] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

6.11. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

6.16. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 7. Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

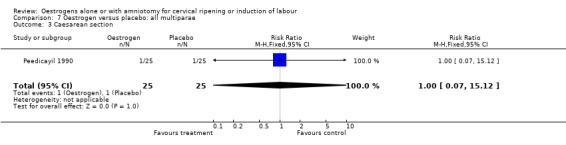

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.81] |

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

7.11. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

7.16. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 8. Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.81] |

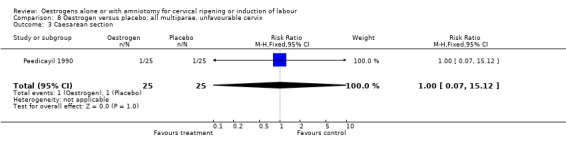

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

8.11. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

8.16. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Oestrogen versus placebo: all multiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 9. Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.61] |

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Oestrogen versus placebo: all primiparae, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

Comparison 10. Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

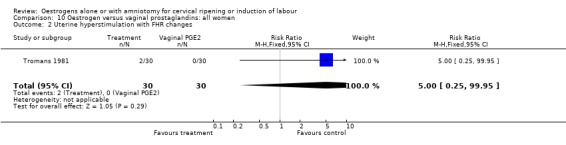

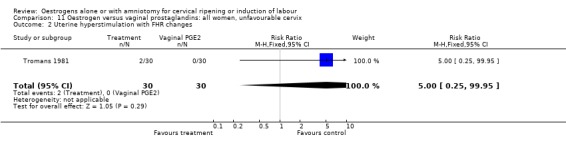

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.95] |

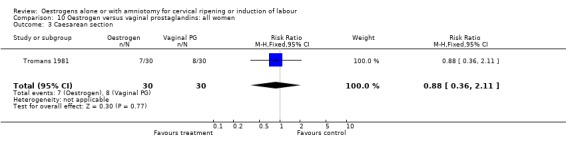

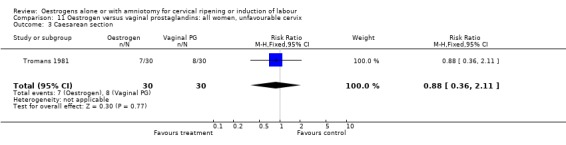

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.36, 2.11] |

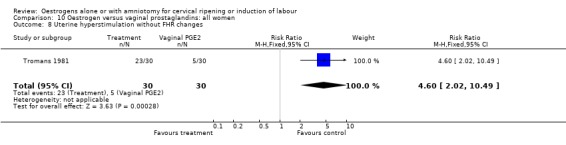

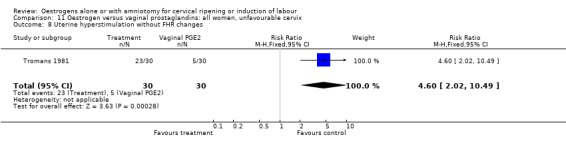

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.6 [2.02, 10.49] |

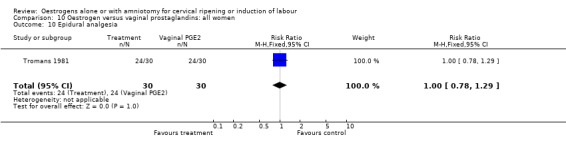

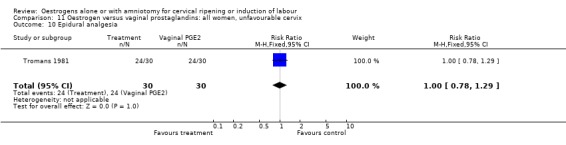

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.78, 1.29] |

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

10.10. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

Comparison 11. Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.95] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.36, 2.11] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.6 [2.02, 10.49] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.78, 1.29] |

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

11.8. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

11.10. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oestrogen versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

Comparison 15. Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.90, 1.95] |

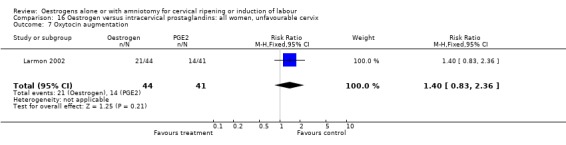

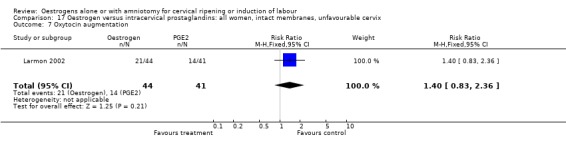

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.83, 2.36] |

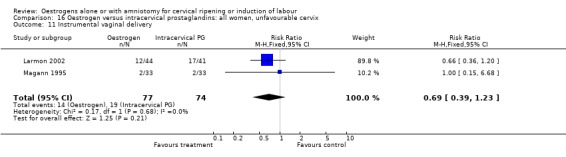

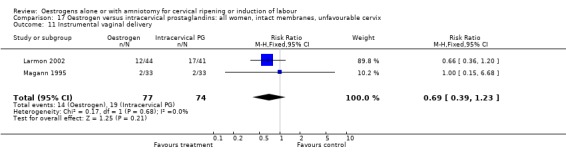

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.39, 1.23] |

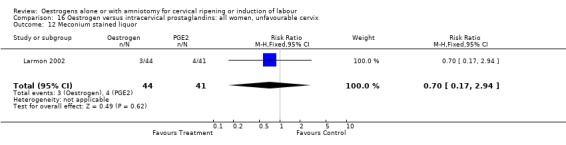

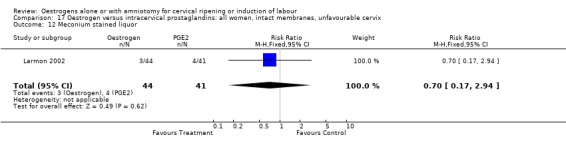

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.17, 2.94] |

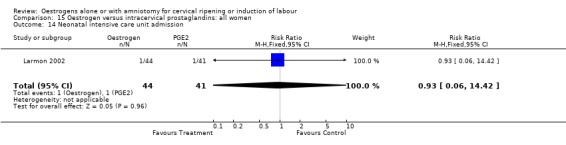

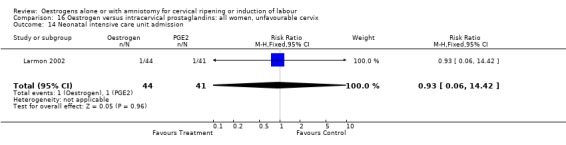

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.06, 14.42] |

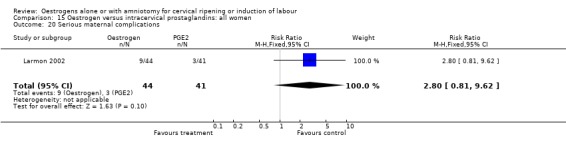

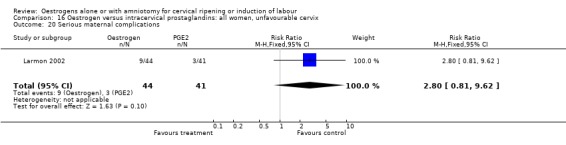

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.80 [0.81, 9.62] |

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

15.7. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

15.11. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

15.12. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

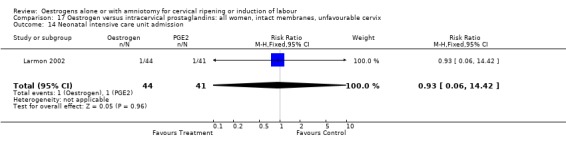

15.14. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

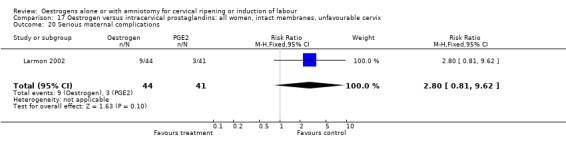

15.20. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 16. Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

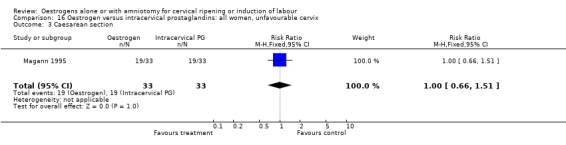

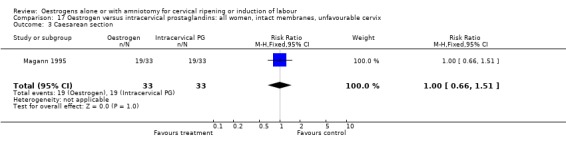

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.66, 1.51] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.83, 2.36] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.39, 1.23] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.17, 2.94] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.06, 14.42] |

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.80 [0.81, 9.62] |

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

16.7. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

16.11. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

16.12. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

16.14. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

16.20. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 17. Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.66, 1.51] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.83, 2.36] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.39, 1.23] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.17, 2.94] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.06, 14.42] |

| 20 Serious maternal complications | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.80 [0.81, 9.62] |

17.3. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

17.7. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

17.11. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

17.12. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

17.14. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

17.20. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Oestrogen versus intracervical prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 20 Serious maternal complications.

Comparison 20. Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

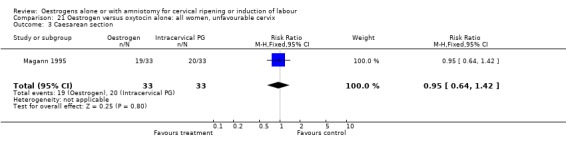

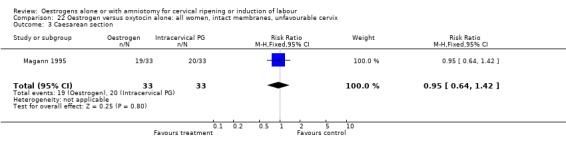

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.64, 1.42] |

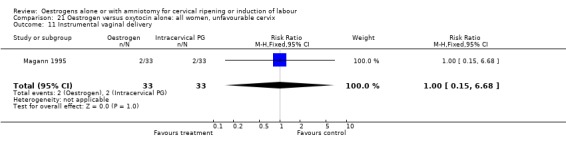

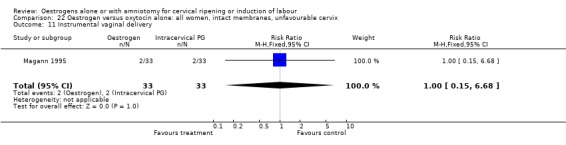

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.68] |

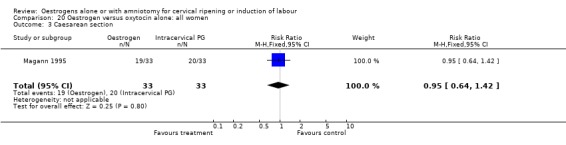

20.3. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

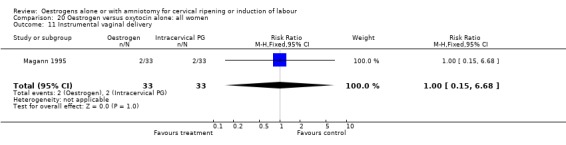

20.11. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 21. Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.64, 1.42] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.68] |

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

21.11. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 22. Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.64, 1.42] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.68] |

22.3. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

22.11. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Oestrogen versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 25. Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

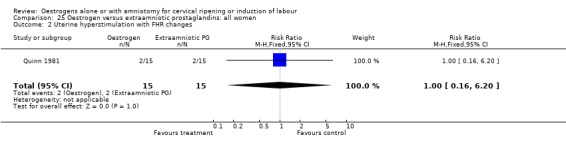

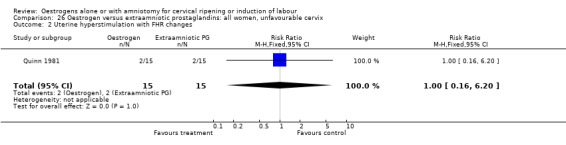

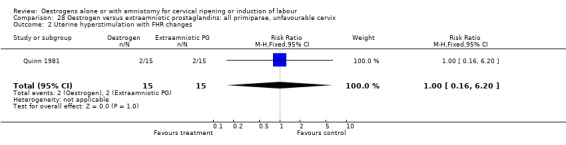

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.20] |

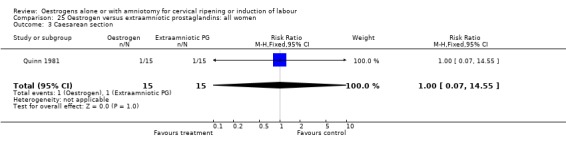

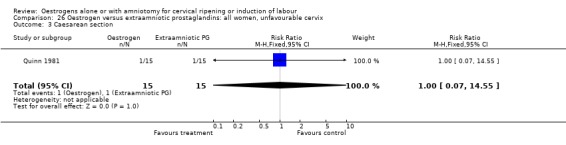

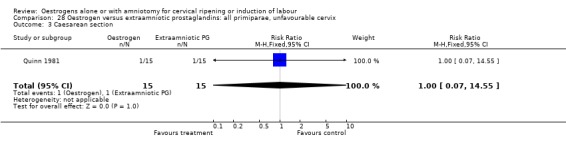

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.55] |

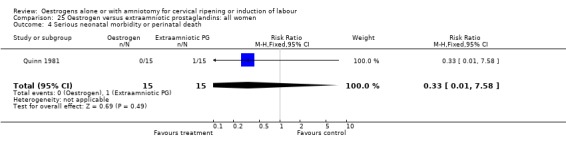

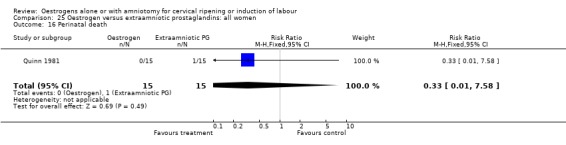

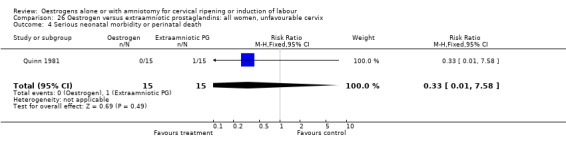

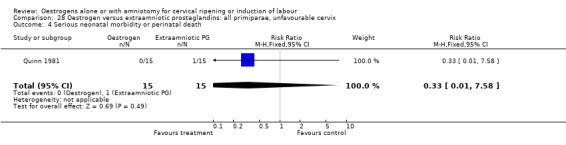

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

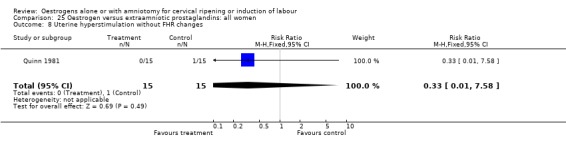

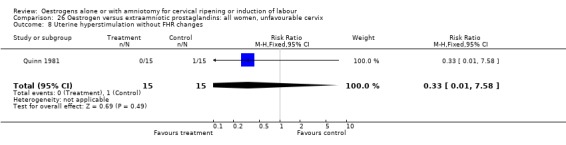

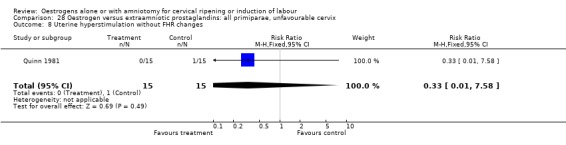

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

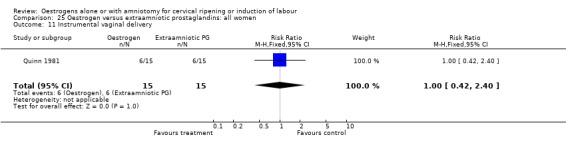

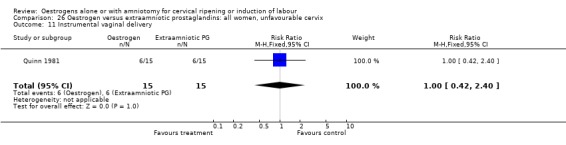

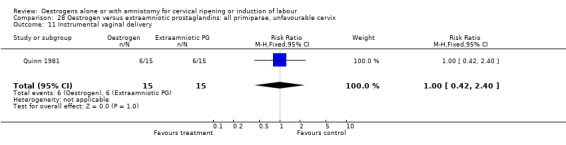

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.42, 2.40] |

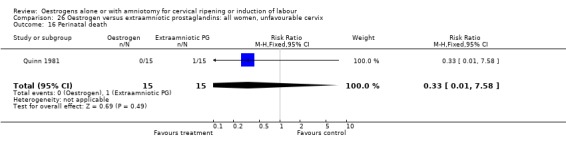

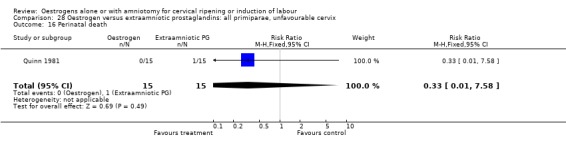

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

25.2. Analysis.

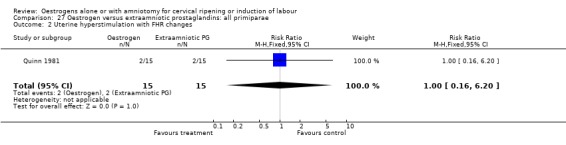

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

25.3. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

25.4. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

25.8. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

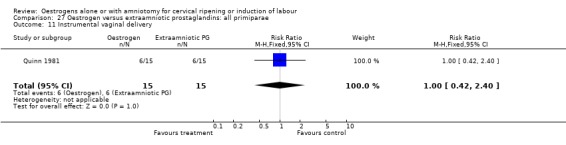

25.11. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

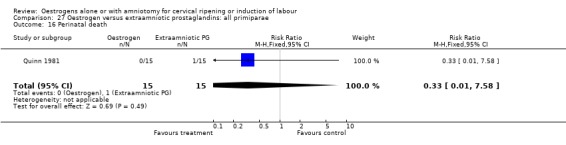

25.16. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 26. Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.20] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.55] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.42, 2.40] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

26.2. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

26.3. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

26.4. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

26.8. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

26.11. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

26.16. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 27. Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.20] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.55] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.42, 2.40] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

27.2. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

27.3. Analysis.

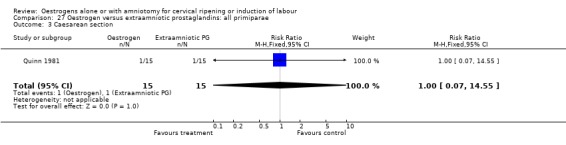

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

27.4. Analysis.

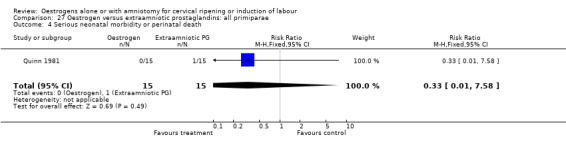

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

27.8. Analysis.

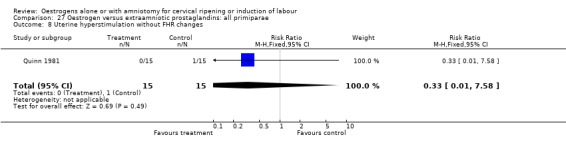

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

27.11. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

27.16. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Comparison 28. Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.20] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.55] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.42, 2.40] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

28.2. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

28.3. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

28.4. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

28.8. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

28.11. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

28.16. Analysis.

Comparison 28 Oestrogen versus extraamniotic prostaglandins: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Klopper 1962.

| Methods | No mention of method of randomisation or concealment. | |

| Participants | 44 nulliparous women, > 37 weeks pregnant. Not stated if IP or OP setting | |

| Interventions | 10 mg oral oestradiol (20 mg initially, followed by 10 mg 6 hourly) vs placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section. | |

| Notes | Not stated if inpatient or outpatient setting, University of Aberdeen, UK. Two trials reported, only smaller first trial is definite RCT. Funding not stated but Intervention and placebo donated by pharmaceutical company Organnon. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Larmon 2002.

| Methods | Randomisation by random number tables, concealment by opaque numbered envelopes. | |

| Participants | 87 pregnant women> 37 weeks, unfavourable cervix (Bishops score <6), outpatient setting. | |

| Interventions | 0.5 mg PGE2 intracervical gel versus 4 mg vaginal oestrogen gel versus inert gel. All given weekly until spontaneous labour or membrane rupture. No maximum specified. | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section, oxytocin augmentation, instrumental vaginal delivery, meconium stained liquor, neonatal intensive care unit admission, serious maternal complications. | |

| Notes | Outpatient setting. University of Mississippi Medical centre, USA. Funded in part by the Vicksburg Medical Foundation, Mississippi. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Magann 1995.

| Methods | Computer generated sequence, allocation by sealed opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 99 pregnant women (33 in each treatment group), with intact membranes, Bishops score < 4. Setting not stated but probably an inpatient setting. | |

| Interventions | 4 mg vaginal oestradiol cream (6 hourly, max 3 doses) vs 0.5 mg intracervical PGE2 gel (6 hourly, max 3 doses) vs IV oxytocin (starting at 1mU/min increased every 30 minutes). | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section, instrumental vaginal delivery. | |

| Notes | University of Mississippi Medical centre, USA. Setting not stated but probably an inpatient setting. Source of funding not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Peedicayil 1990.

| Methods | Randomisation method unclear, concealment by coded drug boxes. | |

| Participants | 50 Multiparae, unfavourable cervix (Bishops score < 3), singleton, cephalic, > 37 weeks. Not stated if IP or OP. | |

| Interventions | 150 mg extra amniotic oestradiol vs extra amniotic placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section, perinatal mortality, instrumental vaginal delivery. | |

| Notes | Christian medical college and hospital, Vellore, India.

Setting not stated but probably an inpatient. Source of funding not stated. Unclear from report to what volume the catheter was inflated to. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Pinto 1967.

| Methods | Alternation used for allocation. | |

| Participants | 100 pregnant women > 36 weeks. Inpatients. | |

| Interventions | 200 mg single dose of IV oestradiol vs IV placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Caesarean section. | |

| Notes | University of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Inpatient setting. Source of funding not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Quinn 1981.

| Methods | Randomisation method not mentioned. Drugs prepared in coded bottles. | |

| Participants | 25 Nulliparous women with modified Bishops score, 3. Inpatients for procedure. | |

| Interventions | 15 mg extra amniotic oestradiol vs 10 mg extra amniotic PGF2a vs extra amniotic placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Uterine hyperstimulation, caesarean section, instrumental vaginal delivery, perinatal death. | |

| Notes | Dalhousie university, Halifax, Canada. Inpatient setting. Source of funding not stated. Prostaglandin supplied by Upjohn pty Ltd and Hoechst Australia Ltd supplied the Tylose gel. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Tromans 1981.

| Methods | Allocation by date of admission. | |

| Participants | 60 women with singleton cephalic pregnancy, > 37 weeks, presentation unfavourable cervix < 4 on modified Bishops score. Inpatients. | |

| Interventions | 150 mg intravaginal oestradiol vs 4 mg vaginal PGE2 Both in a tylose gel. | |

| Outcomes | Uterine hyperstimulation, caesarean section, epidural analgesia. | |

| Notes | Royal Liverpool Hospital, UK. Inpatient setting. Source of funding not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

SRM=artificial rupture of the membranes IV = intravenous

IP = inpatient

min = minimum max = maximum

OP = outpatient RCT = randomised controlled trial vs = versus

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Gordon 1977 | Complex intervention. Both groups had extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (balloon inflated to 20 mls) with either extra‐amniotic oestrogen or placebo. |

| Griffin 2003 | No prespecified outcomes reported in usable format. 35 women randomised to either 12 mg oestradiol twice a day for two days or placebo as outpatients prior to Induction of labour. The main outcome measured was change (improvement) in Bishops score. Published as abstract. |

| Klopper 1969 | Not an induction trial, but uterine activity study. ARM given and then intra‐amniotic oestriol sulphate at onset of labour to test if myometrial activity is modified. |

| Klopper 1973 | Uterine activity study. No pre‐specified outcomes reported. |

| Luther 1980 | Complex intervention. groups randomised to either 10 mg intramuscular estradiol valerate or placebo followed by oral prostaglandin E2. |

| Magnani 1986 | Report of two trials. First trial compares vaginal oestrogen with placebo, but no pre‐specified outcomes are reported. The second trial involves a complex intervention of oestrogen or placebo followed by extra‐amniotic prostaglandin 12 hours later. |

| Mamo 1994 | No pre‐specified outcomes reported. |

| Martin 1955 | IOL for failed abortion. |

| Moran 1994 | No prespecified outcomes reported. 28 women included, 17 received rectal estriol and 11 received placebo. The outcome was measurement of plasma progesterone levels. |

| Palmero 1997 | No pre‐specified outcomes reported. |

| Pedersen 1981 | No pre‐specified outcomes reported. |

| Peedicayil 1989 | Complex intervention, Both groups had extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (balloon inflated to 10mls) with either extra‐amniotic oestrogen or placebo. |

| Roztocil 1998 | Complex intervention. Second phase allocated on Bishops score. |

| Sasaki 1982 | Induction with Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate versus placebo. |

| Stewart 1981 | Complex intervention. Both groups had extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (balloon inflated to 20 mls) with either extra‐amniotic oestrogen or placebo. |

| Thiery 1978 | No pre‐specified outcomes reported. |

| Thiery 1979 | Complex intervention. Both groups had extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (balloon inflated to 20 mls) with either extra‐amniotic oestrogen or placebo. |

| Williams 1988 | Indications for induction included fetal death. |

ARM = artificial rupture of the membranes IOL = induction of labour

Contributions of authors

J Thomas, AJ Kelly and J Kavanagh were involved in developing the protocol, data extraction, assessment of the trials and drafting and re‐drafting the review.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Klopper 1962 {published data only}

- Klopper AI, Dennis KJ. Effect of oestrogens on myometrial contractions. BMJ 1962;2:1157‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larmon 2002 {published data only}

- Larmon JE, Magann EF, Dickerson GA, Morrison JC. Outpatient cervical ripening with prostaglandin E2 and estradiol. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2002;11:113‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 1995 {published data only}

- Magann EF, Perry KG, Dockery JR, Bass JD, Chauhan SP, Morrison JC. Cervical ripening before medical induction of labor: a comparison of prostaglandin E2, estradiol, and oxytocin. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;172:1702‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peedicayil 1990 {published data only}

- Peedicayil A, Jasper P, Balasubramaniam N, Jairaj P. A randomized controlled trial of extra‐amniotic ethinyloestradiol for cervical ripening in multiparas. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;30:127‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pinto 1967 {published data only}

- Pinto RM, Leon C, Mazzocco N, Scasserra U. Action of estradiol‐17B at term and at onset of labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1967;98:540‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quinn 1981 {published data only}

- Quinn MA, Murphy AJ, Kuhn RJP, Robinson HP, Brown JB. A double blind trial of extra‐amniotic oestriol and prostaglandin F2alpha gels in cervical ripening. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1981;88:644‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tromans 1981 {published data only}

- Tromans PM, Beazley JM, Shenouda PI. Comparative study of oestradiol and prostaglandin E2 vaginal gel for ripening the unfavourable cervix before induction of labour. BMJ 1981;282:679‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Gordon 1977 {published data only}

- Gordon AJ, Calder AA. Oestradiol applied locally to ripen the unfavourable cervix. Lancet 1977;2:1319‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Griffin 2003 {published data only}

- Griffin C. Outpatient cervical ripening using sequential oestrogen ‐ a randomised controlled pilot study [abstract]. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2003;43:183. [Google Scholar]

Klopper 1969 {published data only}

- Klopper AI, Dennis KJ, Farr V. Effect of intra‐amniotic oestriol sulphate on uterine contractions. BMJ 1969;2:786‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klopper 1973 {published data only}

- Klopper AI, Farr V, Dennis KJ. The effect of intra‐amniotic oestriol sulphate on uterine contractility at term. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1973;80:34‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Luther 1980 {published data only}

- Luther ER, Roux J, Popat R, Gardner A, Gray J, Soubiran E, Korcaz Y. The effect of estrogen priming on induction of labor with prostaglandins. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1980;137:351‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magnani 1986 {published data only}

- Magnani M, Cabrol D. Induction of labour with PGE2 after cervical ripening with oestradiol. Control and Management of Parturition. Paris: INSERM, 1986:109‐18. [Google Scholar]

Mamo 1994 {published data only}

- Mamo J. Intravaginal oestriol pessary for preinduction cervical ripening. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 1994;46:137. [Google Scholar]

Martin 1955 {published data only}

- Martin, RH, Menzies, DN. Oestrogen therapy in missed abortion and labour. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1955;62:256‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moran 1994 {published data only}

- Moran DJ, McGarrigle HHG, Lachelin GCL. Maternal plasma progesterone levels fall after rectal administration of estriol. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1994;78(1):70‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Palmero 1997 {published data only}

- Palermo MSF, Damiano MS, Lijdens E, Cassale E, Monaco A, Gamarino S, et al. Dinoprostone vs. oestradiol for induction to delivery. Clinical controlled trial. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1997;76:97. [Google Scholar]

Pedersen 1981 {unpublished data only}

- Pedersen S, Moller‐Petersen J, Aegidius J. Comparison of oestradiol and prostaglandin E2 vaginal gel for ripening the unfavourable cervix. BMJ 1981;282:1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Moller‐Petersen, Egidius J. The effect on induction of labour of endocervical balloon catheter with and without oestrogen therapy [Effekten pa fodselsigangsaettelse af endocerviklat balonkateter med og uden ostraiolbehandling]. Ugeskrift for Laeger 1975;143:3379‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peedicayil 1989 {published data only}

- Peedicayil A, Jasper P, Balasubramaniam N, Jairaj P. A randomized controlled trial of extra‐amniotic ethinyloestradiol in ripening the cervix at term. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1989;96:973‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roztocil 1998 {published data only}

- Roztocil A, Pilka L, Jelinek J, Koudelka M, Miklica J. A comparison of three preinduction cervical priming methods: prostaglandin e2 gel, dilapan s rods and estradiol gel. Ceska Gynekologie 1998;63:3‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sasaki 1982 {published data only}

- Sasaki K, Nakano R, Kadoya Y, Iwao M, Shima K, Sowa M. Cervical ripening with dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1982;89:195‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stewart 1981 {published data only}

- Stewart P, Kennedy JH, Barlow DH, Calder AA. A comparison of oestradiol and prostaglandin E2 for ripening the cervix. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1981;88:236‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thiery 1978 {published data only}

- Thiery M, Gezelle H, Kets H, Voorhoof L, Verheugen C, Smis B, et al. Extra‐amniotic oestrogens for the unfavourable cervix. Lancet 1978;2:835‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thiery 1979 {published data only}

- Thiery M, Gezelle H, Kets H, Voorhoof L, Verheugen B, Sims J, et al. The effect of locally adminstered estrogens on the human cervix. Zeitschrift fur Geburtshilfe und Perinatologie 1979;183:448‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 1988 {published data only}

- Williams JK, Lewis ML, Cohen GR, O'Brien WF. The sequential use of estradiol and prostaglandin E2 topical gels for cervical ripening in high‐risk term pregnancies requiring induction of labour. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;158:55‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alfirevic 2006

- Alfirevic Z, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001338.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2001

- Boulvain M, Kelly A, Lohse C, Stan C, Irion O. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001233] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2005

- Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000451.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulvain 2008