Abstract

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether patients using a mobile monitoring system with clinician access experienced improvements in depression symptoms and psychological well-being.

Introduction

Early detection and monitoring of mental health symptoms are crucial, yet many patients and clinicians are unable to receive timely and reliable indicators of clinical progress. Mobile monitoring systems allow for passive tracking of vocal and behavioral indicators of symptoms and can provide infrastructure to securely store, analyze, and provide feedback to patients and clinicians.1 However, the evidence for the effectiveness of mobile monitoring systems in clinical settings is limited.2 We conducted a randomized clinical trial to assess whether patients using a mobile monitoring system with clinician access experienced improvements in depression symptoms and well-being.

Methods

Recruitment

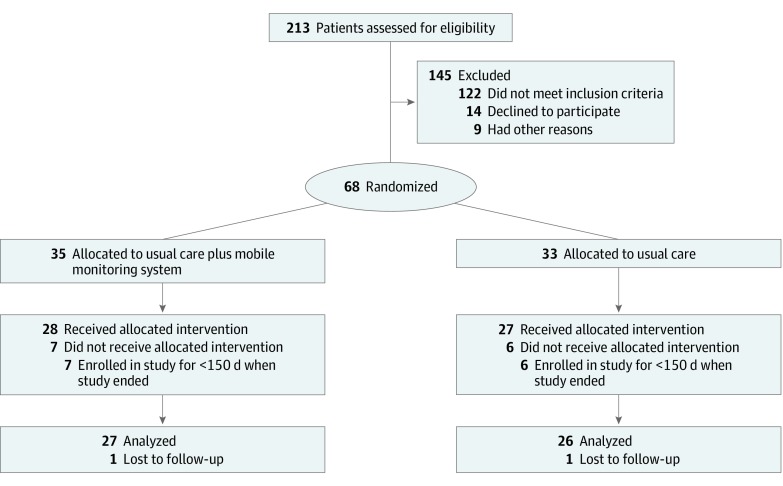

Between February 2016 and June 2017, patients from 2 Brigham and Women’s Hospital Patient-Centered Medical Homes with colocated primary care and behavioral services were recruited through clinician referrals, online advertising, and within-clinic advertising. Exclusion criteria included the presence of a psychotic disorder, suicidal or homicidal risk, history of a cognitive disorder, or not owning an Android smartphone (Figure 1). Researchers obtained Partners Healthcare institutional review board approval and written informed consent from all participants. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1.

Figure 1. Profile of Enrollment in the Randomized Clinical Trial.

Mobile Monitoring System

Patients were randomized to receive usual care (control) or usual care plus the mobile monitoring system (intervention). Patients in the intervention group downloaded the mobile monitoring application to their smartphones. For the 6-month study duration, the application passively collected metadata on smartphone use, including short message service logs, call logs, and geolocation data. Metadata were analyzed against 3 previously modeled Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) diagnostic criteria for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, including fatigue, social isolation, and diminished interest.1 Patients could also leave short audio recordings through the application, which enabled voice feature analyses and provided an additional measure of depressed mood. Visual feedback on these 4 metrics were provided to patients via the mobile application (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2) and to clinicians via a desktop dashboard (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Clinicians were trained to review the dashboard as part of daily workflows, weekly team huddles, and routine clinical visits with patients in the intervention group.

Outcome Measures

At baseline and 6-month follow-up, patients completed the 2 following primary outcome measures: the Patient Health Questionnaire3 sum score for depression severity, ranging from no depressive symptoms (0-4) to severe major depression (>20), and the Schwartz Outcome Scale4 sum score, ranging from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating better overall psychological health. A subset of patients in the intervention group completed questions at follow-up on their level of comfort with sharing data with clinicians and whether the application changed their patient-clinician communication. Patients were asked whether they believed this mobile monitoring system respected their privacy (range, 0-10, with 10 indicating very much so).

We used 2 mixed-design 1-within, 1-between analyses of variance with repeated measures on the assessment time factor for our 2 primary outcomes, ie, the Patient Health Questionnaire and the Schwartz Outcome Scale. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, and all tests were 2-tailed. Data were analyzed beginning in July 2018. Final data analysis was conducted in November 2019. All analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software version 25 (IBM Corp). Additional detail appears in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Results

Sixty-eight patients were randomized (33 to usual care and 35 to usual care plus the mobile monitoring system). Among them, 55 patients (40 [73%] women; 18 [33%] non-Hispanic white; 14 [25%] non-Hispanic black/African American; 11 [20%] Hispanic/Latinx; mean [SD] age, 36.8 [12.9 ] years) received usual care (27 [49%]) or usual care plus the mobile monitoring system (28 [51%]) as allocated. Overall, 53 patients (96%) completed follow-up surveys, and from the intervention group, 15 patients (54%) completed the user experience survey.

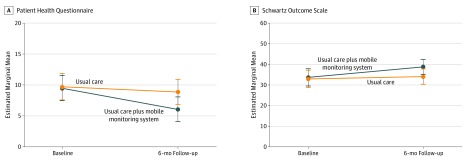

Analysis of variance revealed a significant treatment-by-time interaction effect, supporting decreased depressive symptoms (F1,51 = 4.36; P = .042; partial η2 = 0.08) and improved psychological health (F1,51 = 4.24; P = .045; partial η2 = 0.08) among patients receiving the mobile monitoring system compared with usual care (Figure 2). A total of 12 patients (80%) from the intervention group who completed the user experience survey reported that they would likely or definitely share mobile monitoring data with clinicians. Eight (53%) reported that the mobile monitoring application had at least somewhat improved their communication with clinicians, and 4 (27%) reported directly discussing scores with their clinicians. Patients felt the application respected their privacy (mean [SD] score, 8.80 [1.82]).

Figure 2. Depressive Symptoms and Psychological Health During the Study Period.

Scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire range from no depressive symptoms (0-4) to severe major depression (>20). Scores on the Schwartz Outcome Scale range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating better overall psychological health. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial, patients using a mobile monitoring system with clinician access showed significant improvement on depressive symptoms and psychological health compared with patients receiving usual care. This study has limitations, includings its small sample size in 1 metropolitan area in the northeastern United States. These results provide initial empirical support for the effectiveness of mobile monitoring systems in outpatient clinical settings.5 Future research will test the intervention in additional clinical populations and examine potential mechanisms by which information on symptoms is associated with clinical decisions and behavioral health outcomes.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methodological Descriptions

eFigure 1. Patient View of Mobile Monitoring System Smartphone Application

eFigure 2. Clinician View of Desktop Dashboard

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Place S, Blanch-Hartigan D, Rubin C, et al. Behavioral indicators on a mobile sensing platform predict clinically validated psychiatric symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(3):e75. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S, Nilsen WJ, Abernethy A, et al. Mobile health technology evaluation: the mHealth evidence workshop. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):-. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blais MA, Lenderking WR, Baer L, et al. Development and initial validation of a brief mental health outcome measure. J Pers Assess. 1999;73(3):359-373. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7303_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, et al. The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):287-298. doi: 10.1002/wps.20472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplemental Methodological Descriptions

eFigure 1. Patient View of Mobile Monitoring System Smartphone Application

eFigure 2. Clinician View of Desktop Dashboard

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement