Abstract

Background

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a distressing condition, which is often treated with psychological therapies. Earlier versions of this review, and other meta‐analyses, have found these to be effective, with trauma‐focused treatments being more effective than non‐trauma‐focused treatments. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2005 and updated in 2007.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychological therapies for the treatment of adults with chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References) all years to 12th April 2013. This register contains relevant randomised controlled trials from: The Cochrane Library (all years), MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date), and PsycINFO (1967 to date). In addition, we handsearched the Journal of Traumatic Stress, contacted experts in the field, searched bibliographies of included studies, and performed citation searches of identified articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of individual trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TFCBT), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), non‐trauma‐focused CBT (non‐TFCBT), other therapies (supportive therapy, non‐directive counselling, psychodynamic therapy and present‐centred therapy), group TFCBT, or group non‐TFCBT, compared to one another or to a waitlist or usual care group for the treatment of chronic PTSD. The primary outcome measure was the severity of clinician‐rated traumatic‐stress symptoms.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data and entered them into Review Manager 5 software. We contacted authors to obtain missing data. Two review authors independently performed 'Risk of bias' assessments. We pooled the data where appropriate, and analysed for summary effects.

Main results

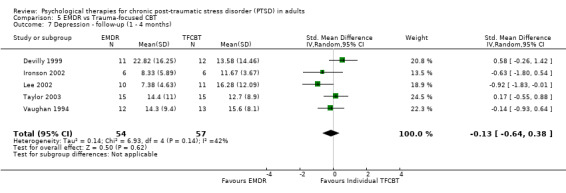

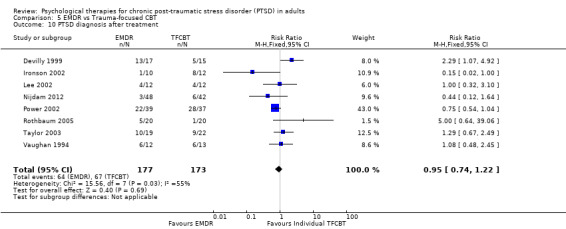

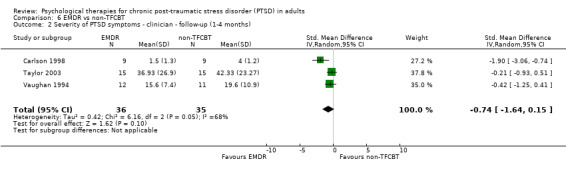

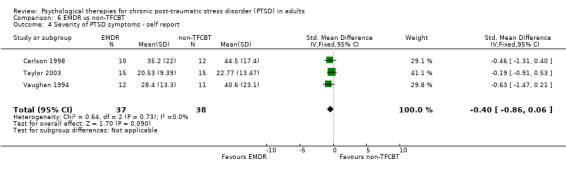

We include 70 studies involving a total of 4761 participants in the review. The first primary outcome for this review was reduction in the severity of PTSD symptoms, using a standardised measure rated by a clinician. For this outcome, individual TFCBT and EMDR were more effective than waitlist/usual care (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐1.62; 95% CI ‐2.03 to ‐1.21; 28 studies; n = 1256 and SMD ‐1.17; 95% CI ‐2.04 to ‐0.30; 6 studies; n = 183 respectively). There was no statistically significant difference between individual TFCBT, EMDR and Stress Management (SM) immediately post‐treatment although there was some evidence that individual TFCBT and EMDR were superior to non‐TFCBT at follow‐up, and that individual TFCBT, EMDR and non‐TFCBT were more effective than other therapies. Non‐TFCBT was more effective than waitlist/usual care and other therapies. Other therapies were superior to waitlist/usual care control as was group TFCBT. There was some evidence of greater drop‐out (the second primary outcome for this review) in active treatment groups. Many of the studies were rated as being at 'high' or 'unclear' risk of bias in multiple domains, and there was considerable unexplained heterogeneity; in addition, we assessed the quality of the evidence for each comparison as very low. As such, the findings of this review should be interpreted with caution.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence for each of the comparisons made in this review was assessed as very low quality. This evidence showed that individual TFCBT and EMDR did better than waitlist/usual care in reducing clinician‐assessed PTSD symptoms. There was evidence that individual TFCBT, EMDR and non‐TFCBT are equally effective immediately post‐treatment in the treatment of PTSD. There was some evidence that TFCBT and EMDR are superior to non‐TFCBT between one to four months following treatment, and also that individual TFCBT, EMDR and non‐TFCBT are more effective than other therapies. There was evidence of greater drop‐out in active treatment groups. Although a substantial number of studies were included in the review, the conclusions are compromised by methodological issues evident in some. Sample sizes were small, and it is apparent that many of the studies were underpowered. There were limited follow‐up data, which compromises conclusions regarding the long‐term effects of psychological treatment.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Behavior Therapy; Behavior Therapy/methods; Chronic Disease; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Psychotherapy, Group; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic; Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic/psychology; Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic/therapy

Plain language summary

Psychological therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults

Background: Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur following a traumatic event. It is characterised by symptoms of re‐experiencing the trauma (in the form of nightmares, flashbacks and distressing thoughts), avoiding reminders of the traumatic event, negative alterations in thoughts and mood, and symptoms of hyper‐arousal (feeling on edge, being easily startled, feeling angry, having difficulties sleeping, and problems concentrating).

Previous reviews have supported the use of individual trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TFCBT) and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) in the treatment of PTSD. TFCBT is a variant of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which includes a number of techniques to help a person overcome a traumatic event. It is a combination of cognitive therapy aimed at changing the way a person thinks, and behavioural therapy, which aims to change the way a person acts. TFCBT helps an individual come to terms with a trauma through exposure to memories of the event. EMDR is a psychological therapy, which aims to help a person reprocess their memories of a traumatic event. The therapy involves bringing distressing trauma‐related images, beliefs, and bodily sensations to mind, whilst the therapist guides eye movements from side to side. More positive views of the trauma memories are identified, with the aim of replacing the ones that are causing problems.

TFCBT and EMDR are currently recommended as the treatments of choice by guidelines such as those published by the United Kingdom's National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

Study characteristics: This review draws together up‐to‐date evidence from 70 studies including a total of 4761 people.

Key findings: There is continued support for the efficacy of individual TFCBT, EMDR, non‐TFCBT and group TFCBT in the treatment of chronic PTSD in adults. Other non‐trauma‐focused psychological therapies did not reduce PTSD symptoms as significantly. There was evidence that individual TFCBT, EMDR and non‐TFCBT are equally effective immediately post‐treatment in the treatment of PTSD. There was some evidence that TFCBT and EMDR are superior to non‐TFCBT between one to four months following treatment, and also that individual TFCBT, EMDR and non‐TFCBT are more effective than other therapies. No specific conflicts of interest were identified.

Quality of the evidence: Although we included a substantial number of studies in this review, each only included small numbers of people and some were poorly designed. We assessed the overall quality of the studies as very low and so the findings of this review should be interpreted with caution. There is insufficient evidence to show whether or not psychological therapy is harmful.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy versus Waitlist/Usual Care | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure Therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Trauma Focused CBT/ Exposure Therapy | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician‐rated in the intervention groups was | 1.62 standard deviations lower (2.03 to 1.21 lower) | 1256 (28 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.64 (1.30 to 2.06) | 1756 (33 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 130 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (150 to 240) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 85 per 1000 | 124 per 1000 (99 to 157) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged to pose a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

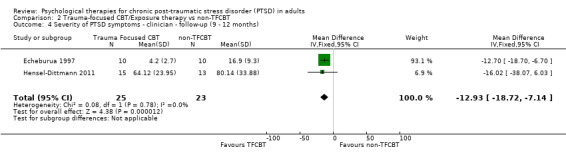

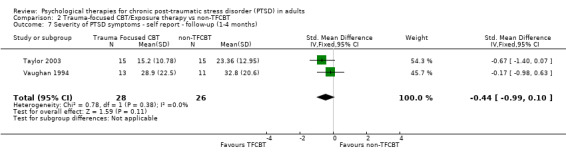

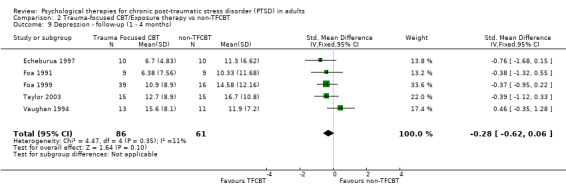

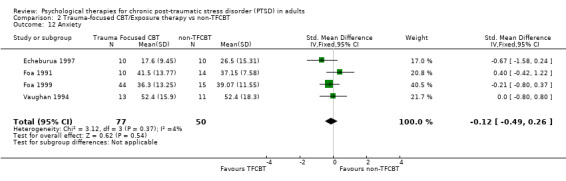

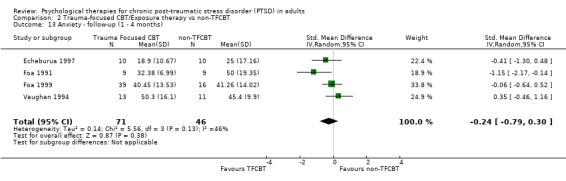

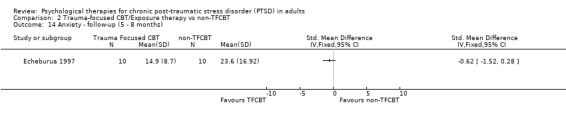

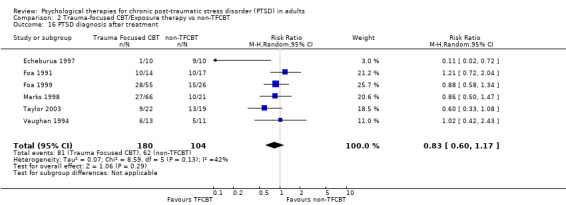

Summary of findings 2. Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy compared with non‐TFCBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy compared with non‐TFCBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy Comparison: non‐Trauma‐focused CBT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Non‐TFCBT | Trauma Focused CBT/ Exposure Therapy | |||||

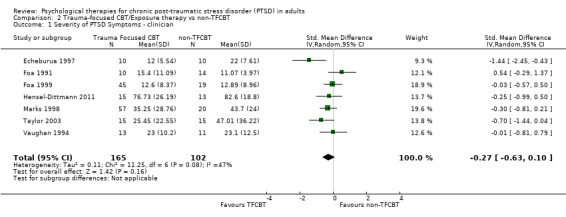

| Severity of PTSD Symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician‐rated in the intervention groups was 0.27 standard deviations lower (0.63 lower to 0.10 higher) | 267 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.19 (0.71 to 2.00) | 312 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 154 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (109 to 308) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 154 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (109 to 308) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged to pose a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

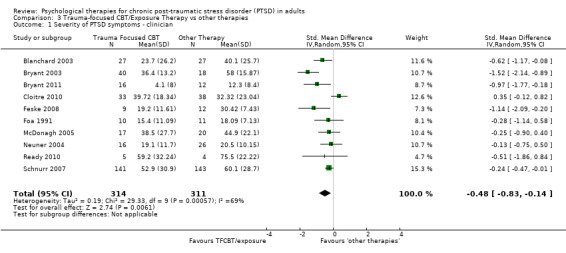

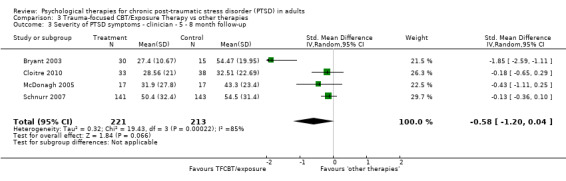

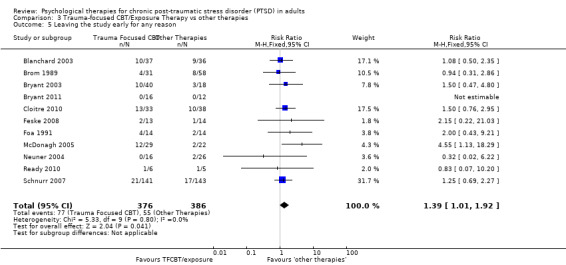

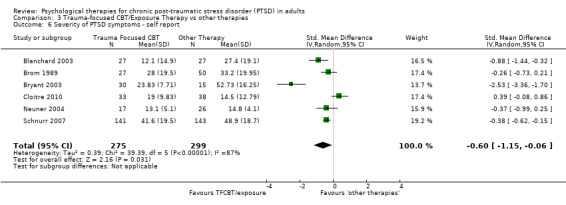

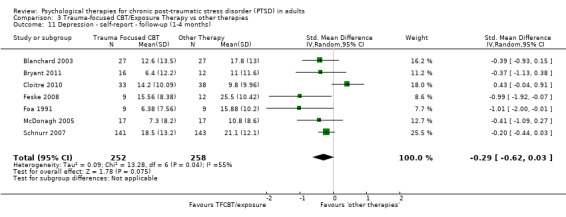

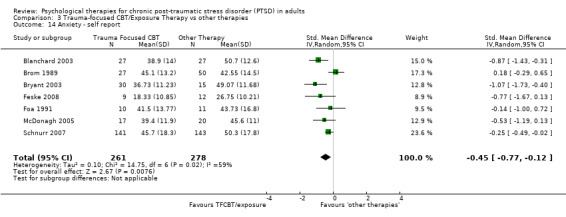

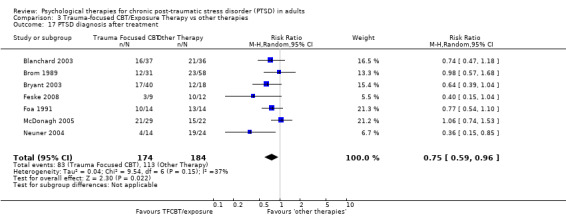

Summary of findings 3. Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy Comparison: other therapies | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Other Therapies | Trauma Focused CBT/Exposure Therapy | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was | ‐0.48 standard deviations lower (‐0.83 to ‐0.43 lower) | 612 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.39 (1.01 to 1.92) | 762 (11 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 142 per 1000 | 198 per 1000 (144 to 274) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 138 per 1000 | 192 per 1000 (139 to 265) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged to pose a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

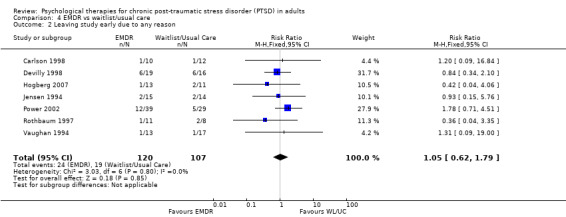

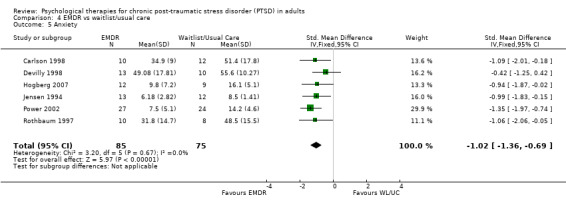

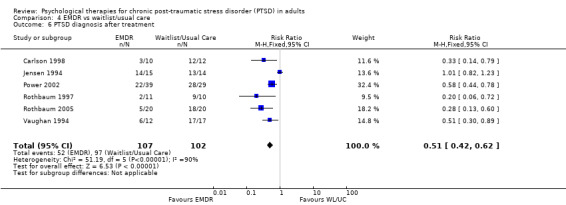

Summary of findings 4. EMDR compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| EMDR compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Comparison: Waitlist/Usual Care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Waitlist/Usual Care | EMDR | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was | 1.17 standard deviations lower (2.04 to 0.30 lower) | 183 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| Leaving study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.62 to 1.79) | 227 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 | ||

| 178 per 1000 | 188 per 1000 (104 to 313) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 172 per 1000 | 182 per 1000 (101 to 305) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged to pose a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

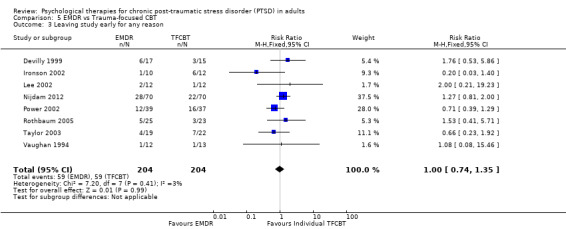

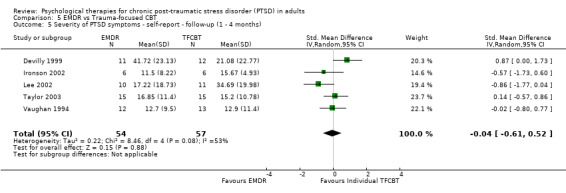

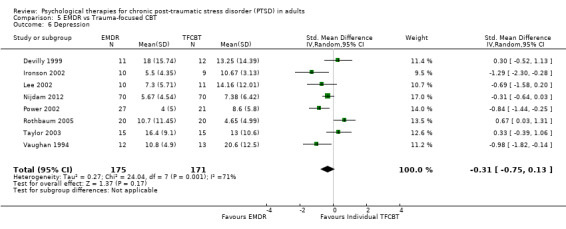

Summary of findings 5. EMDR compared with Trauma‐focused CBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| EMDR compared with Trauma‐focused CBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Comparison: Trauma‐focused CBT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Trauma Focused CBT | EMDR | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was | 0.03 standard deviations lower (0.43 lower to 0.38 higher) | 327 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| Leaving study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.74 to 1.35) | 400 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 279 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (191 to 367) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 257 per 1000 | 247 per 1000 (174 to 342) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged as posing a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

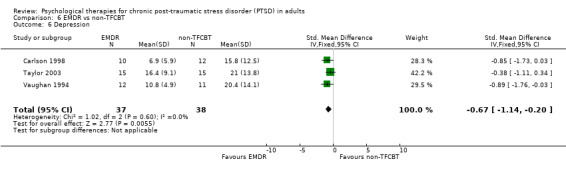

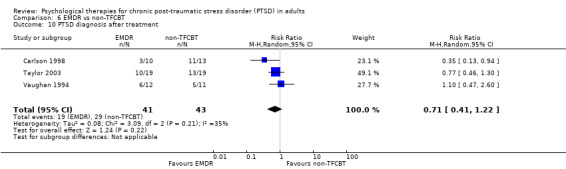

Summary of findings 6. EMDR compared with non‐TFCBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| EMDR compared with non‐TFCBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Comparison: non‐trauma‐focused CBT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Non‐TFCBT | EMDR | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was | 0.35 standard deviations lower (0.90 lower to 0.19 higher) | 53 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.37 to 2.88) | 84 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 140 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (46 to 367) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 91 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (29 to 264) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Studies reported insufficient information to judge risk of bias 2Small sample sizes. Only two studies.

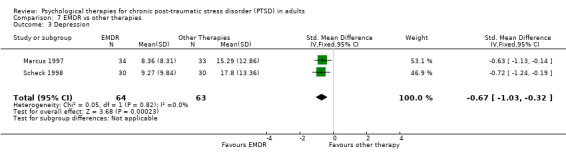

Summary of findings 7. EMDR compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| EMDR compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Comparison: other therapies | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Other Therapies | EMDR | |||||

| Leaving study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.48 (0.26 to 8.54) | 127 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 32 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (8 to 234) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 32 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (8 to 236) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1One study was judged to pose a high risk of bias. The other study reported insufficient information for a judgement to be made 2Only two studies. Small sample sizes

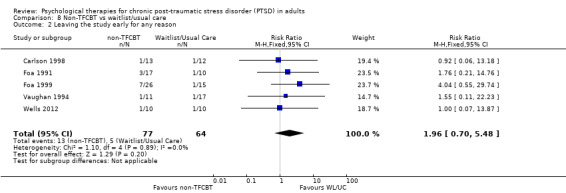

Summary of findings 8. Non‐TFCBT compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Non‐TFCBT compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: non‐trauma‐focused CBT Comparison: Waitlist/Usual Care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Waitlist/Usual Care | Non‐TFCBT Therapy | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was 1.22 standard deviations lower (1.76 to 0.69 lower) | 106 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Leaving the study early due to any reason | Study population | RR 1.96 (0.70 to 5.48) | 141 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 78 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (55 to 428) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 83 per 1000 | 163 per 1000 (58 to 455) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Insufficient data to judge risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

Summary of findings 9. Non‐TFCBT compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Non‐TFCBT compared with other therapies for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: non‐trauma‐focused CBT Comparison: other therapies | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Non‐TFCBT | ||||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clincian‐rated | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 25 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Leaving the study early for any reason | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Some studies were judged to pose a high risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

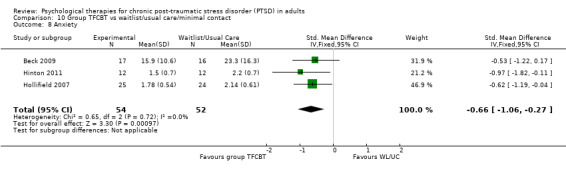

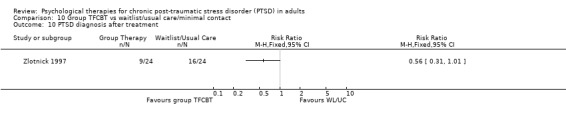

Summary of findings 10. Group TFCBT compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Group TFCBT compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Group TFCBT Comparison: Waitlist/Usual Care/Minimal Contact | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Group TFCBT | ||||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was 1.28 standard deviations lower (2.25 to 0.31 lower) | 185 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.94 to 1.55) | 573 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 262 per 1000 | 317 per 1000 (246 to 406) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 242 per 1000 (188 to 310) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Insufficient information to judge risk of bias 2Unexplained heterogeneity 3Small sample sizes

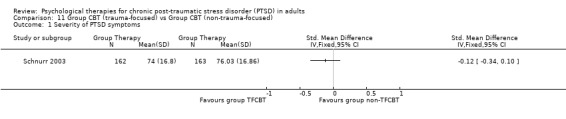

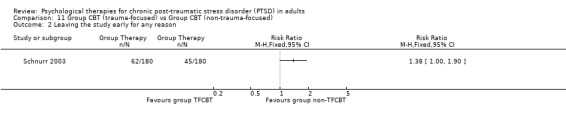

Summary of findings 11. Group TFCBT compared with Group non‐TFCBT for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Group CBT (trauma focused) compared with Group CBT (non‐trauma focused) for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Group TFCBT Comparison: Group non‐TFCBT | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Group CBT (non‐trauma focused) | Group CBT (trauma focused) | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 325 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| Leaving the study early for any reason | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 360 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Insufficient information to judge risk of bias 2One study with a small sample size

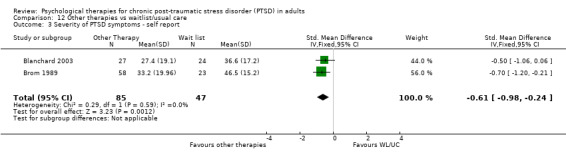

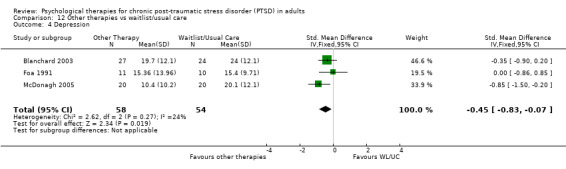

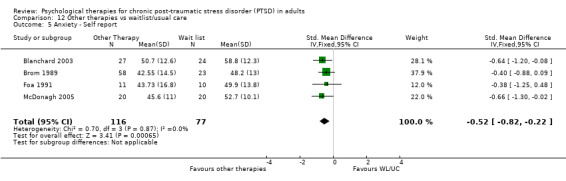

Summary of findings 12. Other therapies compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Other therapies compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Other therapies Comparison: Waitlist/Usual Care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Waitlist/Usual Care | Other therapies | |||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ Clinician | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician in the intervention groups was 0.58 standard deviations lower (0.96 to 0.20 lower) | 112 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |||

| Leaving the study early due to any reason | Study population | RR 2.45 (0.99 to 6.10) | 211 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 74 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (73 to 452) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 72 per 1000 | 176 per 1000 (71 to 439) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Small sample sizes 2Studies were judged to pose a low/unclear risk of bias

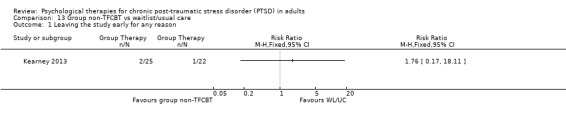

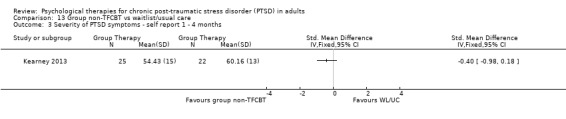

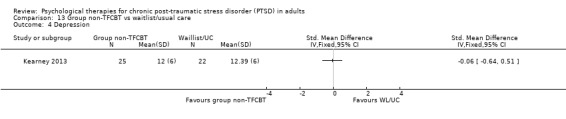

Summary of findings 13. Group non‐TFCBT compared with Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults.

| Group non‐TFCBT compared to Waitlist/Usual Care for chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adults with PTSD for at least 3 months Settings: Primary care, community, outpatient Intervention: Group non‐TFCBT Comparison: Waitlist/Usual Care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Waitlist/Usual Care | Group nonTFCBT | |||||

| Leaving the study early for any reason | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Only one study. Risk of bias high/unclear in several domains. 2Only one study

Background

Description of the condition

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a well recognised psychiatric disorder that occurs following a major traumatic event. Characteristic symptoms include re‐experiencing phenomena such as nightmares and recurrent distressing thoughts of the event, avoidance of talking or being reminded of the traumatic event, negative alterations in thoughts and mood, and hyperarousal symptoms including sleep disturbance, increased irritability and hypervigilance. PTSD can be diagnosed after a one‐month duration of symptoms. The condition is considered chronic once symptoms have been present for three months. PTSD is a relatively common condition. The National Co‐morbidity Survey (Kessler 1995) found that 7.8% of 5877 American adults had suffered from PTSD at some time in their lives. When data were examined from individuals who had been exposed to a traumatic event, rates of PTSD varied according to the type of stressor. For example, physical assaults amongst women led to a lifetime prevalence of 29% and combat experience amongst men to a lifetime prevalence of 39%.

Description of the intervention

Psychological therapies have been advocated as being effective in the treatment of PTSD since its conception. Various forms of psychological therapy have been used including exposure therapy (Creamer 2004), cognitive therapy (Ehlers 2005; Resick 1992), psychodynamic psychotherapy (Brom 1989) and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (Shapiro 1989b). Exposure therapy usually involves asking the participant to relive the trauma imaginally. This is often done by creating a detailed present tense account of exactly what happened, making an audio tape recording or transcript of it and asking the individual to listen to/read this over and over again. Another form of exposure therapy involves exposing participants to cues associated with the traumatic event (for example, graded re‐exposure to car travel following a road traffic accident). Trauma‐focused cognitive therapy involves helping the individual to identify distorted thinking patterns regarding themselves, the traumatic incident and the world. Individuals are encouraged to challenge their thoughts by weighing up available evidence and through the utilisation of various techniques by the therapist, including specific questioning that leads the individual to challenge distorted views. EMDR involves the PTSD sufferer focusing on a traumatic image, thought, emotion and a bodily sensation whilst receiving bilateral stimulation, most commonly in the form of eye movements. Non‐TFCBT usually focuses on techniques for the reduction of anxiety. The most widely used protocol for anxiety reduction in PTSD is stress inoculation training (SIT), which teaches skills for managing stress, such as relaxation, thought stopping and guided dialogue. It provides the opportunity to practise acquired skills gradually, across a variety of settings. Psychodynamic psychotherapy focuses on integrating the traumatic experience into the life experience of the individual as a whole; childhood issues are often felt to be important.

How the intervention might work

The psychological therapies considered by this review stem from various theoretical perspectives. Individual protocols describe how therapies might work in detail. TFCBT protocols draw on four core components emphasised in varying degrees: 1) psycho‐education; 2) anxiety management; 3) exposure; and 4) cognitive restructuring. Earlier therapies tended to be more behaviourally based, focusing heavily on exposure work. Cognitive components have become more prominent over time, in line with the popularity of information processing accounts of the disorder. Exposure plays an important role in many TFCBT protocols. It may be carried out in vivo (real life), or imaginally. It is common for both to be used in the treatment of PTSD, to target internally and externally feared stimuli. The rationale behind the use of imaginal exposure varies according to the specific TFCBT protocol. Imaginal exposure is based on principles of habituation (the reduction of anxiety after prolonged exposure) or information processing (allowing re‐evaluation of old information and incorporation of new information into the trauma memory), or a combination of both. In addition, cognitive restructuring has an important role, seeking to identify and modify dysfunctional thoughts by testing and challenging self‐held beliefs, based on the assumption that these usually unquestioned thoughts are distorted or unhelpful. EMDR is an integrative trauma‐focused therapy encompassing elements from various effective psychotherapies in a structured protocol drawn from an information processing model of PTSD. There is no agreed mechanism by which EMDR is thought to operate. Shapiro 1989b discovered EMDR accidentally. Her account implicates personal experience of rapid eye movements easing distress. On the basis of this experience, Shapiro elaborated EMDR for the treatment of Vietnam war veterans and abuse sufferers. It is suggested that bilateral stimulation aids the processing of traumatic memories. Non‐TFCBT interventions such as SIT operate by teaching the individuals techniques to minimise and control their anxiety. In terms of other psychological therapies considered by this review, psychodynamic psychotherapy places emphasis on the unconscious mind, aiming to resolve inner conflict arising from the traumatic event. Person‐centred therapy/supportive counselling allows the individual to talk through problems and resolve difficulties with minimal guidance and direction from the therapist. The therapist is accepting and non‐judgemental. This style encourages the individual to feel comfortable in the expression of feelings, facilitating positive change. Unlike trauma‐focused therapies, person‐centred/supportive counselling does not encourage exploration of the trauma memory.

For a summary of psychological models of PTSD providing the rationale for many of the treatment approaches considered here, see Brewin 2003.

Why it is important to do this review

It is apparent that PTSD causes clinically significant suffering and that developing effective interventions is important. Earlier versions of this review and other meta‐analyses have found psychological therapies to be effective (e.g. Bradley 2005), with trauma‐focused treatments being more effective than non‐trauma‐focused treatments (Bisson 2007a). This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2005 and updated in 2007, bringing together current evidence concerning the psychological treatment of chronic PTSD in adults. Other Cochrane Collaboration reviews have considered single‐session psychological 'debriefing' to prevent PTSD (Rose 2002), multiple‐session early psychological interventions for the prevention of PTSD (Roberts 2009), early psychological therapies to treat acute traumatic stress symptoms (Roberts 2010), pharmacological treatments (Stein 2006), combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for PTSD (Hetrick 2010), and psychological therapies for the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents (Gillies 2012).

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychological therapies for the treatment of adults with chronic post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological therapies for chronic PTSD in adults. Cluster‐RCTs and cross‐over trials were considered eligible for inclusion. We did not use sample size, language or publication status to determine whether or not a study was included.

Types of participants

Age

This review considered studies of adults only (aged 18 or over).

Diagnosis

Any individual suffering from chronic traumatic stress symptoms, i.e. with a duration of three months or more. At least 70% of participants were required to be diagnosed as suffering from PTSD according to DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐IIIR (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 2000),ICD‐9 (WHO 1979) or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992) criteria, by means of a structured interview or diagnosis by a clinician. There was no restriction on the basis of severity of PTSD symptoms or the type of traumatic event.

Co‐morbidities

There was no restriction on the basis of comorbidity, although we required that PTSD be the primary diagnosis.

Setting

There was no restriction on the basis of study setting.

Types of interventions

This review considered any psychological therapy designed to reduce symptoms of chronic PTSD. Group interventions were considered separately from those delivered on an individual basis. Psychological therapy provided in a group format is clinically distinct from its individually‐delivered counterparts, not least due to the reduced therapist 'dose' associated with group therapy.

Experimental interventions

Individual trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TFCBT): any psychological therapy that predominantly used trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques. This category included exposure therapy. Examples of therapies within this category are cognitive therapy (Ehlers 2005), cognitive processing therapy (Resick 1992) and prolonged exposure (Foa 2000).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (Shapiro 1989b).

Non‐trauma‐focused CBT: any psychological therapy that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques, for example stress inoculation training (SIT) (Meichenbaum 1988).

Group TFCBT: any approach delivered in a group setting that predominantly used trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques.

Group non‐TFCBT: any approach delivered in a group that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques.

Other psychological therapy: any psychological therapy that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused techniques that would not be considered cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques. This category comprised non‐directive/supportive/person‐centred counselling (Rogers 1961), hypnotherapy, psychodynamic therapy (Brom 1989) and present‐centred treatment.

Comparator interventions

Waitlist, treatment as usual, symptom monitoring, repeated assessment or other minimal attention control group;

An alternative psychological treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Reduction in the severity of PTSD symptoms using a standardised measure (i.e. a test that is administered and scored in a consistent way) rated by a clinician (e.g. the Clinician Administered PTSD Symptom Scale (Blake 1995)).

Drop‐out rates.

Secondary outcomes

Severity of self‐reported traumatic stress symptoms using a standardised measure (e.g. the Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz 1979)).

Severity of depressive symptoms (e.g. the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961)).

Severity of anxiety symptoms using scales (e.g. the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger 1973)).

PTSD diagnosis after treatment.

Any adverse effects, e.g. increased PTSD symptoms.

We produced hierarchies of the standardised measures, based on their frequency of use within the included studies. Where a trial reported data from two or more measures of the same outcome, we used only data from the measure ranked highest.

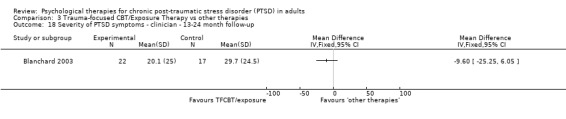

Timing of outcome assessment

We conducted separate pair‐wise meta‐analyses of follow‐up data at one to four months, five to eight months, nine months to one year, and over one year.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 33,000 reports of randomised controlled trials in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of OVID MEDLINE (1950‐), EMBASE (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization’s trials portal (ICTRP), ClinicalTrials.gov, drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies can be found on the Group's website.

We searched the CCDANCTR (Studies and References Registers, all years to 12th April 2013) on condition alone, using the following terms: (PTSD or posttrauma* or post‐trauma* or “post trauma*” or (combat and disorder*))

Searching other resources

Grey literature We searched abstracts from meetings of the European and International Societies of Traumatic Stress Studies. We also searched websites and discussion fora related to PTSD.

Handsearching We handsearched the Journal of Traumatic Stress and the ISTSS Treatment Guidelines (Foa 2000; Foa 2009) for relevant articles.

Reference lists We scrutinised the reference lists of included studies for additional studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Correspondence The main correspondence was with the UK NICE guidelines development group who kindly shared the results of their searches and communications (see Acknowledgements).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently read abstracts of all potential trials identified through the search strategy. If we felt an abstract represented a possible RCT, each review author independently read the full report to determine if the trial met the inclusion criteria. Any differences prompted re‐evaluation of the study, and we discussed disagreements with a third review author to reach a consensus.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from published reports and entered them into Review Manager 5 Software (RevMan 5). We contacted authors to obtain missing information. Extracted data included demographic details of participants, details of the traumatic event, the randomisation process, the therapy used, and outcome data.

Main comparisons

Individual TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care

Individual TFCBT versus non‐TFCBT

Individual TFCBT versus other therapies

EMDR versus waitlist/usual care

EMDR versus individual TFCBT

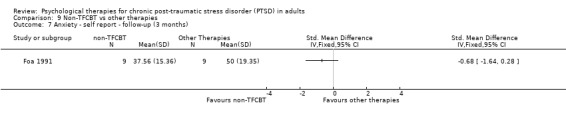

EMDR versus non‐TFCBT

EMDR versus other therapies

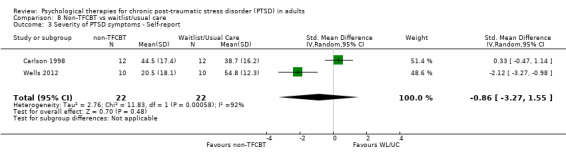

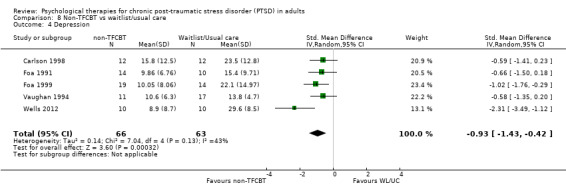

Non‐TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care

Non‐TFCBT versus other therapy

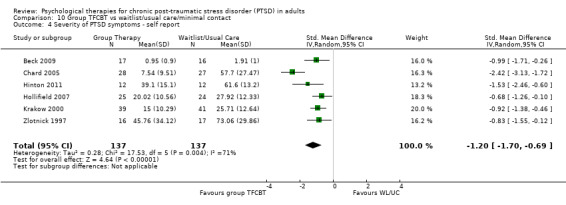

Group TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care

Group TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT

Other therapies versus waitlist/usual care

Group non‐TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care

Individual TFCBT versus group TFCBT

Individual TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT

EMDR versus group TFCBT

EMDR versus group non‐TFCBT

Individual non‐TFCBT versus group TFCBT

Individual non‐TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed all included studies for risk of bias, using the standard approach described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This considered (1) sequence allocation for randomisation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of personnel and assessors; (4) incomplete outcome data; (5) selective reporting; and (6) any other notable risks of bias. Each was judged to pose a 'high', 'low' or 'unclear' risk of bias. Two review authors conducted the assessments, discussing any disagreements with a third review author to reach a consensus.

1. Sequence allocation randomisation

Randomisation was judged as posing a 'low' risk of bias if each participant had an equal chance of being randomised to a group. Low‐risk methods included referring to a random number table, use of a computerised random number generator, shuffling sealed envelopes or throwing a dice. Methods judged as posing a 'high' risk of bias included use of a sequence generated by e.g. date of birth, clinic number, date of admission to the study, or allocation by availability of the intervention. When insufficient information was given to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias, we describe the study as being at an 'unclear' risk of bias attributable to sequence allocation.

2. Allocation concealment

Concealment of intervention allocation was said to be at 'low' risk when there was no chance of the investigator foreseeing a participant's assignment. Methods judged as posing a low risk of bias included central allocation (e.g. by telephone or the internet) or sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes. High‐risk methods included alternation or rotation of assignment or using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers). When insufficient information was reported to permit judgement of high or low risk, we describe the study as being at an 'unclear' risk of bias attributable to allocation concealment.

3. Blinding of personnel and assessors

It is not possible to blind either the participants or those administering psychological interventions. However, outcome assessors can be blinded. Those studies which blinded assessors were deemed to be at a low risk of bias, those which did not were judged as being at a high risk of bias. When insufficient information was reported to permit judgement of high or low risk, we describe the study as being at an 'unclear' risk of bias attributable to blinding.

4. Incomplete outcome data

We judged incomplete data to have been handled appropriately when reported completely, including attrition rates and exclusions, with consideration of the issue in terms of analysing the data. Low risk of bias was associated with no missing outcome data, or the use of data imputed using appropriate methods. Methods judged as posing a high risk of bias included analyses that considered only the data of treatment‐completers, or potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. When insufficient information was reported to permit judgement of high or low risk, we describe the study as being at an 'unclear' risk of bias attributable to incomplete data.

5. Selective reporting

We judged a study to be at a low risk of bias if a protocol was available and all prespecified outcomes were reported. If there was no available protocol, the study was assigned a low risk in this domain if it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those prespecified. When insufficient information was reported to permit judgement of high or low risk, we describe the study as being at an 'unclear' risk of bias attributable to selective reporting.

6. Other notable risks of bias

We noted any other potential threats to validity and judged them to be at a high or low risk of bias. We describe them as being at 'unclear' risk of bias when there was insufficient information to assess additional risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

We analysed continuous outcomes as standardised mean differences (SMDs) to allow ease of comparison across studies. All outcomes are presented using 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Dichotomous data

We analysed categorical outcomes as risk ratios (RRs), these being more widely used in medical practice than odds ratios. All outcomes are presented using 95% confidence intervals.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

We included only outcome data from the first randomisation period when a study adopted a cross‐over design.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

If the trial had three (or more) arms, we undertook pair‐wise meta‐analysis with each arm, depending upon the nature of the intervention in each arm and the relevance to the review objectives. We avoided multiple comparisons as far as possible, to limit the risk of false positive results. When a study had three or more arms that were relevant to the review we considered the appropriateness of combining data from two arms if therapies were sufficiently similar or of using data from the arms of the trial which fit closest to the review objective. Decisions followed guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011).

Cluster‐randomised trials

We had planned to include cluster‐RCTs, although none was identified by the searches to date. In future updates of the review, the methodology for dealing with these types of studies will follow that outlined by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). We will adjust sample sizes using an estimate of the intracluster or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which describes the 'similarity' of individuals within the same cluster. We will derive this from the trial if possible, or from another source, such as a similar study, or from a resource providing examples of ICCs.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors to obtain any data missing from the published report of included studies. We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data where possible, but used data from completers analyses when ITT data were not available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We initially assessed studies included within each comparison for clinical heterogeneity in terms of variability in the experimental and control interventions, participants and settings, and outcomes. To further assess heterogeneity, we used both the I² statistic (Higgins 2003) and the Chi² test of heterogeneity, as well as visual inspection of the forest plots.

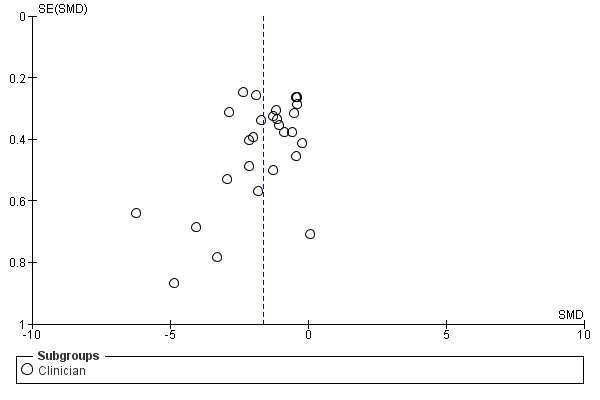

Assessment of reporting biases

When sufficient studies were available, we constructed funnel plots and scrutinised them for signs of asymmetry. Since reporting bias is just one possible reason for observed asymmetry, we also considered alternative explanations.

Data synthesis

We pooled data from more than one study using a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, except where heterogeneity was present, in which case we used a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed clinical heterogeneity subgroup analyses (when sufficient data were available) as follows:

Type of traumatic event (combat‐related trauma versus rape and sexual assault versus other civilian trauma)

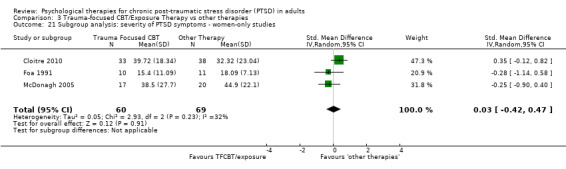

Participant characteristics (men only versus women only)

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of high or unclear risk of bias in any of the following domains:

Sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of outcome assessment

These analyses were performed for comparisons including 10 or more studies.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search yielded 1477 articles for consideration. We reviewed abstracts and obtained full‐text copies for 129 potentially relevant studies. Seventy RCTs (79 comparisons) met the inclusion criteria for the review. Figure 1 presents a flow diagram for study selection.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Design

All included studies were RCTs.

Sample sizes

The number of participants randomised in the trials ranged from 9 (Ready 2010) to 360 (Schnurr 2003). Eleven studies included sample sizes of over 100: Brom 1989 (n = 112); Cloitre 2010 (n = 104); Foa 2005 (n = 171); Krakow 2000 (n = 169); Krakow 2001 (n = 114); Mueser 2008 (n = 108); Nijdam 2012 (n = 140); Power 2002 (n = 105); Resick 2002 (n = 121); Schnurr 2003 (n = 360); Schnurr 2007 (n = 284).

Settings

USA (33 studies), UK (6 studies), Australia (7 studies), Netherlands (4 studies), Hawaii (3 studies), Germany (3 studies), Turkey (2 studies), Sweden (2 studies), Uganda (2 studies), Japan (1 study), Romania (1 study), Thailand (1 study), Canada (1 study), Portugal (1 study), Cambodia (1 study), China (1 study), Spain (1 study).

Participants

The study populations were varied and often not directly comparable (i.e. there was significant clinical heterogeneity). Studies included individuals traumatised by combat (13 studies), sexual assault (13 studies), war/persecution (6 studies), road traffic accidents (4 studies), earthquake (3 studies), childhood sexual abuse (3 studies), political detainment (1 study), terrorism (1 study), sexual or physical assault (1 study) and serving in the police force. The remainder of the studies included individuals traumatised by various traumatic events (24 studies).

Time post‐trauma

All studies included individuals at least three months after the trauma. The range was large, from three months to over 40 years (Bichescu 2007). There was often a wide range of times since trauma included in individual studies.

Interventions

In order to present the results in a meaningful way, we decided to pool data that used a similar theoretical methodology. This was conducted a priori, resulting in the establishment of six groups: individual TFCBT, non‐TFCBT, EMDR, group TFCBT, group non‐TFCBT and other therapies (psychodynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, supportive counselling and present‐centred counselling).

1. Trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy: Forty‐nine studies considered individual TFCBT ‐ Adenauer 2011; Asukai 2010; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bichescu 2007; Blanchard 2003; Brom 1989; Bryant 2003; Bryant 2011; Cloitre 2002; Cloitre 2010; Cooper 1989; Devilly 1999; Duffy 2007; Dunne 2012; Echeburua 1997; Ehlers 2005; Fecteau 1999; Feske 2008; Foa 1991; Foa 1999; Foa 2005; Forbes 2012; Galovski 2012; Gamito 2010; Gersons 2000; Hensel‐Dittmann 2011; Hinton 2005; Ironson 2002; Keane 1989; Kubany 2003; Kubany 2004; Lindauer 2005; McDonagh 2005; Marks 1998; Monson 2006; Mueser 2008; Neuner 2004; Neuner 2008; Neuner 2010; Paunovic 2011; Peniston 1991; Power 2002; Ready 2010; Resick 2002; Schnurr 2007; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994; Nijdam 2012; Zang 2013.

2. Non‐TFCBT: Eight studies considered non‐TFCBT ‐ Carlson 1998; Echeburua 1997; Foa 1991; Foa 1999; Kearney 2013; Marks 1998; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994.

3. Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing: Sixteen studies considered eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing ‐ Carlson 1998; Devilly 1998; Devilly 1999; Hogberg 2007; Ironson 2002; Jensen 1994; Lee 2002; Marcus 1997; Power 2002; Rothbaum 1997; Rothbaum 2005; Scheck 1998; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994; Nijdam 2012. 4. Group TFCBT: Ten studies considered group TFCBT ‐ Beck 2009; Chard 2005; Classen 2001; Hinton 2011; Hollifield 2007; Kearney 2013; Krakow 2000; Krakow 2001; Schnurr 2003; Zlotnick 1997.

5. Group non‐TFCBT: One study considered group non‐TFCBT: Schnurr 2003

6. Other therapies: Nine studies considered other therapies (supportive counselling, present‐centred therapy, hypnotherapy and psychodynamic therapy) ‐ Blanchard 2003; Brom 1989; Bryant 2003; Cloitre 2010; Feske 2008; Foa 1991; McDonagh 2005; Ready 2010; Schnurr 2007.

Comparisons

The included trials compared (i) Psychological therapy versus waitlist or usual care control (some studies allowed the control group to receive pharmacological treatments and/or psychological therapies that were not being considered specifically); (ii) Psychological therapy versus other psychological therapy.

We made the following specific comparisons:

1. Individual TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care:Adenauer 2011; Asukai 2010; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bichescu 2007; Blanchard 2003; Brom 1989; Cloitre 2002; Cooper 1989; Duffy 2007; Dunne 2012; Ehlers 2003; Ehlers 2005; Fecteau 1999; Foa 1991; Foa 1999; Foa 2005; Forbes 2012; Galovski 2012; Gamito 2010; Gersons 2000; Hinton 2005; Keane 1989; Kubany 2003; Kubany 2004; Lindauer 2005; McDonagh 2005; Monson 2006; Mueser 2008; Neuner 2010; Paunovic 2011; Peniston 1991; Power 2002; Resick 2002; Vaughan 1994; Wells 2012; Zang 2013.

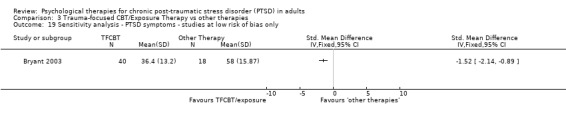

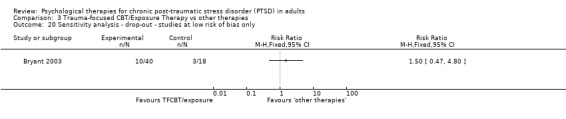

2. Individual TFCBT versus non‐TFCBT:Echeburua 1997; Foa 1991; Foa 1999; Hensel‐Dittmann 2011; Marks 1998; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994.

3.Individual TFCBT versus other therapies:Blanchard 2003; Brom 1989; Bryant 2003; Bryant 2011; Cloitre 2010; Feske 2008; Foa 1991; McDonagh 2005; Neuner 2004; Ready 2010; Schnurr 2007.

4. EMDR versus waitlist/usual care:Carlson 1998; Devilly 1998; Hogberg 2007; Jensen 1994; Power 2002; Rothbaum 1997; Rothbaum 2005; Vaughan 1994.

5. EMDR versus individual TFCBT:Devilly 1999: Ironson 2002: Lee 2002: Nijdam 2012; Power 2002: Rothbaum 2005; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994.

6. EMDR versus non‐TFCBT:Carlson 1998; Taylor 2003; Vaughan 1994.

7. EMDR versus other therapy:Marcus 1997; Scheck 1998.

8. Individual non‐TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care:Carlson 1998; Foa 1991; Foa 1999; Vaughan 1994; Wells 2012.

9. Non‐TFCBT versus other therapy:Foa 1991.

10. Group TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care:Beck 2009; Chard 2005; Hinton 2011; Hollifield 2007; Krakow 2001, Krakow 2000, Zlotnick 1997.

11. Group TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT:Schnurr 2003.

12.Other therapies versus waitlist/usual care:Blanchard 2003; Brom 1989; Foa 1991; McDonagh 2005.

13. Group non‐TFCBT versus waitlist/usual care: no studies

14. Individual TFCBT versus group TFCBT: no studies

15. Individual TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT: no studies

16. EMDR versus group TFCBT: no studies

17. EMDR versus group non‐TFCBT: no studies

18. Individual non‐TFCBT versus group TFCBT: no studies

19. Individual non‐TFCBT versus group non‐TFCBT: no studies

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were reduction in severity of clinician‐rated PTSD symptoms and drop‐out rate. Secondary outcome measures were severity of self‐reported PTSD symptom, severity of depressive symptoms, severity of anxiety symptoms, PTSD diagnosis after treatment and adverse side effects (such as increased PTSD symptoms).

Excluded studies

We excluded studies if they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Some studies made no formal diagnosis of PTSD (Abbasnejad 2007; Classen 2001; Classen 2010; Cole 2007; Edmond 1999; Edmond 2004; Falsetti 2001; Ginzberg 2009; Hiari 2005;, Knaevelsrud 2007; Lange 2001; Lange 2003; Litz 2007; Price 2007; Ryan 2005; Shapiro 1989a; Sloan 2004; Sloan 2005), and in other studies fewer than 70% of participants met full diagnostic criteria for the disorder (Davis 2007; Difede 2007a; DuHamel 2010; Maercker 2006; Rabe 2008; Van Emmerik 2008; Wilson 1995). Other reasons for excluding specific studies were a duration of less than three months following trauma (Echeburua 1996; some participants within, Foa 2006; Spence 2011), treatment did not target traumatic stress symptoms (Dunn 2007; Chemtob 1997), comparison of two psychological therapies in the same category (Arntz 2007; Mithoefer 2011; Paunovic 2001; Tarrier 1999; Watson 1997), the intervention was not a psychological therapy (Gidron 1996), including individuals under 18 years of age (Jaberghaderi 2004; Najavits 2006; Schaal 2009), comparison of two non‐TFCBT therapies, and comparison with pharmacotherapy (Frommberger 2004; Rothbaum 2006).

See Characteristics of excluded studies table for further details.

Studies awaiting classification

Krupnick 2008 is awaiting classification as we need to obtain further information.

Risk of bias in included studies

A graphical representation of the overall risk of bias for each domain and each study is available in Figure 2 and Figure 3 respectively.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence allocation randomisation

Fifteen studies reported a method of allocation that we felt to be appropriate, and which we judged to be at low risk of bias (Adenauer 2011; Asukai 2010; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bryant 2003; Bryant 2011; Fecteau 1999; Hensel‐Dittmann 2011; Hogberg 2007; Hollifield 2007; Lindauer 2005; Neuner 2004; Power 2002; Scheck 1998; Wells 2012). We judged the method of allocation to be at high risk of bias in six studies (Bichescu 2007; Blanchard 2003; Cooper 1989; Devilly 1999; Ehlers 2003; Schnurr 2003). The remainder of the studies reported insufficient information for us to make a judgement.

Allocation concealment

Many studies did not provide full details of the method of randomisation and we therefore judged concealment to be at unclear risk of bias in the majority. Fifteen studies reported adequate allocation concealment, representing a low risk of bias (Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bryant 2011; Cloitre 2010; Duffy 2007; Ehlers 2003; Foa 2005; Forbes 2012; Krakow 2001; Lindauer 2005; Monson 2006; Mueser 2008; Nijdam 2012; Power 2002; Scheck 1998). We judged one study to be at high risk in terms of failure to conceal allocation (Cooper 1989). None of the other studies reported any methods of concealing allocation and we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Blinding

In common with all studies of psychological therapies a double‐blind methodology is virtually impossible, as it is clear to the participant what treatment they are receiving. However, a well‐designed study should ensure blinding of the assessor of outcome measures. In six of the included studies, the assessor was aware of the participant's allocation (Basoglu 2005; Carlson 1998; Ironson 2002; Keane 1989; Marcus 1997; Paunovic 2011). It was unclear whether or not the assessor was blind in 14 studies (Brom 1989; Cooper 1989; Duffy 2007; Dunne 2012; Echeburua 1997; Fecteau 1999; Feske 2008; Forbes 2012; Gamito 2010; Hinton 2011; Jensen 1994; Kearney 2013; Krakow 2000; Scheck 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up

Drop‐out rates were high in many of the studies and reasons for attrition were generally poorly reported. We judged 21 studies to be at high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Adenauer 2011; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Beck 2009; Brom 1989; Carlson 1998; Cooper 1989; Devilly 1998; Devilly 1999; Ehlers 2003; Fecteau 1999; Feske 2008; Foa 1991; Hogberg 2007; Jensen 1994; Krakow 2000; Paunovic 2011; Power 2002; Rothbaum 1997; Rothbaum 2005; Scheck 1998; Zlotnick 1997). It was unclear how missing data were handled in six studies (Gamito 2010; Keane 1989; Marcus 1997; Peniston 1991; Ready 2010). We judged the remainder to have dealt with drop‐outs appropriately, i.e. at low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

It was difficult to draw any meaningful conclusions with regards to the issue of selective reporting. Very few of the included studies had published protocols available. It was therefore impossible to know whether prespecified outcome measures were adequately reported. The majority of studies adequately reported all outcomes outlined within the Methods section of the trial report.

Other potential sources of bias

A strength of the majority of the studies was having clear objectives, but sample sizes were often small and the follow‐up period was limited. The treatments delivered were reasonably well‐described and the majority of studies reported on the credentials and experience of therapists. A high proportion of the included studies made some assessment of treatment adherence. Most studies used well‐validated outcome measures although there was considerable variation in the actual measures used. For practical and ethical reasons there were rarely follow‐up data available from waitlist groups. We could not rule out potential researcher allegiance in many of the studies. A number of the included trials were of interventions that were evaluated by their originators.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13

The full results are contained in the Tables and are summarised below.

Comparison 1. Individual TFCBT/Exposure therapy versus waitlist/usual care

37 studies including 1830 participants contributed to this comparison.

Primary outcomes

1.1. Clinician‐rated PTSD symptoms

Twenty‐eight studies considered this outcome with a total of 1256 individuals (Analysis 1.1). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 237.95, P = 0.00001; I² = 89%) and we used a random‐effects model to pool the data. The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group immediately after treatment (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐1.62; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐2.03 to ‐1.21).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 1 Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ clinician.

At 1‐ to 4‐month follow‐up four studies compared this outcome with 336 individuals (Analysis 1.2). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 52.30; P < 0.00001; I² = 94%). The individual TFCBT group did significantly better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐1.18; 95% CI ‐2.20 to ‐0.17).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 2 Severity of PTSD symptoms at 1 ‐ 4 month follow‐up.

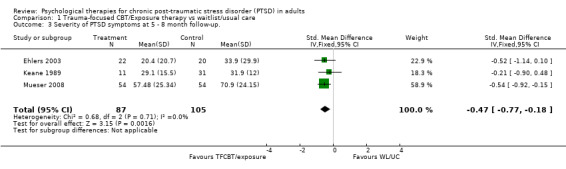

At 5‐ to 8‐month follow‐up three studies compared this outcome with 192 individuals (Analysis 1.3). There was little heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 0.68; P = 0.71; I² = 0%). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.47; 95% CI ‐0.77 to ‐0.18).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 3 Severity of PTSD symptoms at 5 ‐ 8 month follow‐up..

At 9‐ to 12‐month follow‐up one study reported this outcome with 109 individuals (Analysis 1.4). The individual TFCBT group did significantly better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.78; 95% CI ‐1.18 to ‐0.39).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 4 Severity of PTSD symptoms 9 ‐ 12 month follow‐up.

1.2. Drop‐outs

Thirty‐four studies with a total of 1776 individuals recorded whether individuals left the study early for any reason by group (Analysis 1.5). There was considerable clinical heterogeneity between these trials. The individual TFCBT group did significantly worse than the waitlist/usual care group (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.30 to 2.06).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 5 Leaving the study early for any reason.

Secondary outcomes

1.3 Self‐reported PTSD symptoms

Seventeen studies considered this outcome with a total of 686 individuals (Analysis 1.1.4). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 82.15; P < 0.00001; I² = 81%) and we used a random‐effects model to pool the data. The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group immediately after treatment (SMD ‐1.60; 95% CI ‐2.02 to ‐1.18).

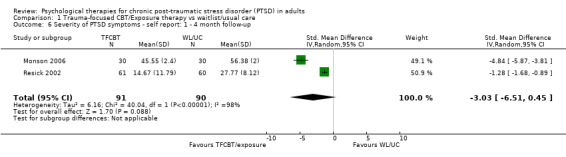

At 1‐ to 4‐month follow‐up two studies compared this outcome with 181 individuals (Analysis 1.6). There was marked heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 40.04; P = 0.00001; I² = 98%). There were no significant differences between groups (SMD ‐3.03; 95% CI ‐6.51 to 0.45).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 6 Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ self report: 1 ‐ 4 month follow‐up.

At 5‐ to 8‐month follow‐up two studies compared this outcome with 208 individuals (Analysis 1.7). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.61; 95% CI ‐0.90 to ‐0.32).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 7 Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ self report: 5 ‐ 8 months).

At 9‐ to 12‐month follow‐up one study compared this outcome with 121 individuals (Analysis 1.8). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐1.22; 95% CI ‐1.61 to ‐0.83).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 8 Severity of PTSD symptoms ‐ self report: 9 ‐ 12 month follow up.

1.4 Depression

Twenty‐nine studies considered this outcome with a total of 1233 individuals (Analysis 1.9). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 174.84, P < 0.00001; I² = 84%) and we used a random‐effects model to pool the data. The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group immediately after treatment (SMD ‐1.31; 95% CI ‐1.65 to ‐0.98).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 9 Depression.

At 1‐ to 4‐month follow‐up seven studies compared this outcome with 413 individuals (Analysis 1.10). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 41.24; P < 0.00001; I² = 85%). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.75; 95% CI ‐1.33 to ‐0.18).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 10 Depression 1 ‐ 4 month follow‐up.

At 5‐ to 8‐month follow‐up two studies compared this outcome with 150 individuals (Analysis 1.11). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.50; 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.17).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 11 Depression 5 ‐ 8 month follow‐up.

At 9‐ to 12‐month follow‐up one study compared this outcome with 108 individuals (Analysis 1.12). The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.60; 95% CI ‐0.99 to ‐0.21).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 12 Depression 9 ‐ 12 month follow‐up.

1.5 Anxiety

Eighteen studies considered this outcome with a total of 664 individuals (Analysis 1.13). There was heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 27.43; P = 0.04; I² = 38%) and we used a random‐effects model to pool the data. The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group immediately after treatment (SMD ‐0.82; 95% CI ‐1.03 to ‐0.61).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 13 Anxiety.

At 1‐to 4‐month follow‐up three studies compared this outcome with 189 individuals (Analysis 1.14). There was little heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 2.16; P = 0.34; I² = 7%). The TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (SMD ‐0.32; 95% CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.03).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 14 Anxiety 1 ‐ 4 month follow‐up.

At 9‐ to 12‐month follow‐up one study compared this outcome with 108 individuals (Analysis 1.15). There was no difference between the two groups (SMD ‐0.33; 95% CI ‐0.71 to 0.05).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 15 Anxiety 9 ‐ 12 month follow‐up.

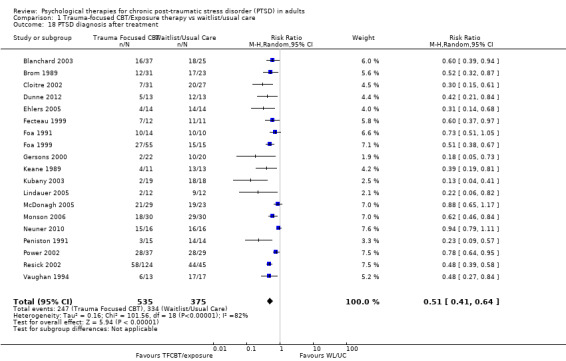

1.6 PTSD diagnosis after treatment

Nineteen studies with a total of 910 individuals reported this outcome (Analysis 1.18). There was significant heterogeneity between these trials (Chi² = 101.56; P < 0.00001; I² = 82%) and we used a random‐effects model to pool the data. The individual TFCBT group did better than the waitlist/usual care group (RR 0.51; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.64).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trauma‐focused CBT/Exposure therapy vs waitlist/usual care, Outcome 18 PTSD diagnosis after treatment.

1.7 Adverse effects