Abstract

Background

Induction of labour is a common obstetric intervention. Amniotomy alone for induction of labour is reviewed separately and oxytocin alone for induction of labour is being prepared for inclusion in The Cochrane Library. This review will address the use of the combination of these two methods for induction of labour in the third trimester. This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardised methodology.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the efficacy and safety of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin for third trimester induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and reference lists of articles were searched. Date of last search: May 2001. We updated the search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register on 21 September 2009 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

Trial quality assessment and data extraction were done by both reviewers. A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was done centrally, and incorporated into a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The data is to be extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by category of woman.

Main results

Seventeen trials involving 2566 women were included. Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin were found to result in fewer women being undelivered vaginally at 24 hours than amniotomy alone (relative risk (RR) 0.03, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.001‐0.49). This finding was based on the results of a single study of 100 women. As regards secondary results amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin resulted in significantly fewer instrumental vaginal deliveries than placebo (RR 0.18, CI 0.05‐0.58). Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin resulted in more postpartum haemorrhage than vaginal prostaglandins (RR 5.5, CI 1.26‐24.07). Significantly more women were also dissatisfied with amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin when compared with vaginal prostaglandins, RR 53, CI 3.32‐846.51.

Authors' conclusions

Data on the effectiveness and safety of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin are lacking. No recommendations for clinical practice can be made on the basis of this review. Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin is a combination of two methods of induction of labour and both methods are utilised in clinical practice. If their use is to be continued it is important to compare the effectiveness and safety of these methods, and to define under which clinical circumstances one may be preferable to another.

[Note: The three citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Amnion; Amnion/surgery; Injections, Intravenous; Labor, Induced; Labor, Induced/methods; Oxytocin; Oxytocin/administration & dosage; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin for induction of labour

Intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy compares well with other forms used in the third trimester (full term) to bring on labour.

Sometimes it is necessary to help get labour started. There are several methods used and they either ripen the cervix or make the uterus start contracting. Oxytocin is a drug used to stimulate contractions of the uterus. Amniotomy (breaking the waters) helps bring on contractions. The review of trials found that oxytocin combined with amniotomy compares well with other forms of labour induction. However, adverse risks of amniotomy include pain and discomfort, bleeding, possible infection in the uterus and a decreased heart rate in the baby. The risk of infection following amniotomy is particularly important in areas where HIV is prevalent.

Background

Induction of labour is a common obstetric intervention which is usually undertaken for a clinical indication, however rightly or wrongly, it may also be undertaken for other reasons, such as a woman's request or clinician's convenience. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

Amniotomy alone for induction of labour and intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour are reviewed separately (Bricker 2001; Tan 2001). This review will address the two in combination. Concomitant administration is regarded when the two are initiated within two hours of each other, irrespective of which is initiated first.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the efficacy and safety of amniotomy plus oxytocin for third trimester induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing amniotomy plus oxytocin for labour induction, with placebo/no treatment or other methods; random allocation to treatment and comparison groups, reasonable measures to ensure allocation concealment; violations of allocated management not sufficient to materially affect outcomes.

Types of participants

Women due for third trimester induction of labour, with a viable fetus. Sub‐group analyses were performed for women regarding parity and subgroups of these for those with favourable, unfavourable or undefined cervices, as well as previous lower segment caesarean section.

Types of interventions

Amniotomy plus oxytocin compared with placebo/no treatment or other methods of induction of labour listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction ‐ See Hofmeyr 2000.

Primary comparisons:

intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment;

intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy versus intra vaginal prostaglandins;

intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy versus intra cervical prostaglandins;

intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin;

intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy.

In the studies of oxytocin and amniotomy versus prostaglandins, the prostaglandins used were PGE2(1‐2mg) in a gel preparation; vaginal pessaries(3mg); PGE2 tablets(3mg); PGE2 in methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose gel(400ug); and PGF2 alpha(50mg).

The oxytocin dosage used varied between studies with a most common maximum dosage of 32 mU/min (16 mU/min‐40 mU/min), flow rate doubled half hourly, with 5% Dextrose in Water used as administration fluid.

Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin were considered as concomitant if the amniotomy was performed within two hours from the start of the oxytocin infusion or vice versa. This time interval was determined before evaluation of studies for inclusion into the review was commenced and was agreed upon by both reviewers. In most studies the two interventions were commenced simultaneously but in five studies this was not specified (Saleh 1975; Thompson 1987; Martin 1978; Ratnam 1974; Kennedy 1978). In two studies failure to rupture the membranes occurred (Maclennan 1989, two women; Orhue 1995, nine women). Amniotomy was, however, successful after oxytocin administration for one to two hours prior to amniotomy.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Sub‐group analyses were limited to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia.

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction:

Measures of effectiveness: (6) cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications: (8) uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium stained liquor; (13) Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction: (26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews we will use the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes 'to include uterine tachysystole (> 5 contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short term variability).

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; missing data were insufficient to materially influence conclusions and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (May 2001). We updated this search on 21 September 2009 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

The original search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

We search the reference lists of trial reports and reviews.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion according to the prestated selection criteria, without consideration of their results. Allocation concealment was scored as A: adequate (e.g. double blind, placebo controlled; envelopes administered centrally) B: unclear (e.g. numbered sealed envelopes not administered centrally) C: inadequate e.g. alternation). Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the presented criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Data were extracted from the sources and entered onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2000), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed effects model. The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis were: trial quality assessment and interval between amniotomy and commencement of oxytocin.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and sub‐group analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or sub‐groups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Results

Description of studies

See 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Intravenous oxytocin and amniotomy were compared with placebo/expectant management in one study (Martin 1978, 184 women ).

Comparisons were made with vaginal prostaglandin in ten studies (Orhue 1995; Dommisse 1987; Thompson 1987; Maclennan 1980; Parazzini 1998; Lamont 1991; Maclennan 1989; Kennedy 1982;Taylor 1993; Melchior 1989; 1169 women).

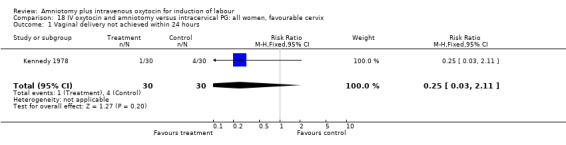

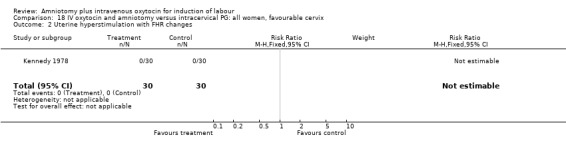

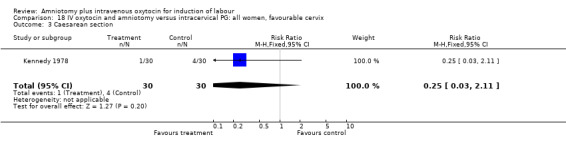

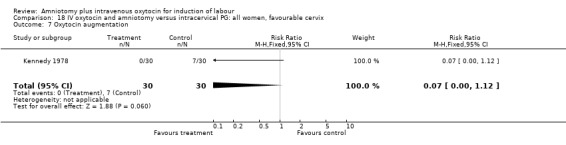

Comparisons were made with intracervical prostaglandin in one study (Kennedy 1978, 90 women).

Comparisons were made with oxytocin alone in two studies (Ratnam 1974, Mercer 1995, 416 women).

Comparisons were made with amniotomy alone in three studies (Saleh 1975, Patterson 1971, Moldin 1996, 707 women).

(Three reports from an updated search in September 2009 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

The majority of the included studies were of good quality: Seven studies scored A: (Lamont 1991; Maclennan 1980; Mercer 1995; Moldin 1996; Orhue 1995; Parazzini 1998; Taylor 1993; with the rest of the studies scoring B: (Dommisse 1987; Kennedy 1978; Kennedy 1982; Patterson 1971; Ratnam 1974; Saleh 1975; Thompson 1987; Maclennan 1989; Martin 1978; Melchior 1989).

Allocation sequence generation was unclear in seven studies ( Kennedy 1978 'randomly allocated'; Kennedy 1982 'randomly allocated'; Lamont 1991 'random' stratified by parity; Patterson 1971; Saleh 1975 'randomly'; Thompson 1987 'randomised'; Melchior 1989, ' randomised in table of four').

Random number tables were used in five studies (Dommisse 1987; Maclennan 1989; Maclennan 1980; Martin 1978; Orhue 1995). Computer generated sequence was used in four studies (Mercer 1995; Moldin 1996; Taylor 1993; Parazzini 1998). In one study, allocation sequence was generated by lot drawing (Ratnam 1974).

Effects of interventions

Seventeen trials involving 2566 women were included.

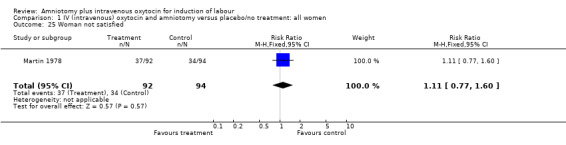

Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin versus placebo or no treatment ‐ all women.

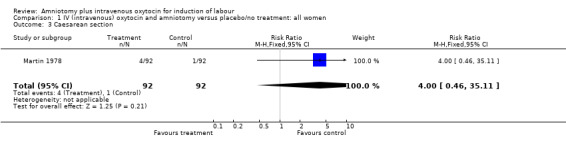

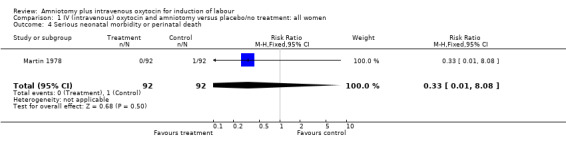

(i) Primary outcomes: One study (Martin 1978), with 184 participants, evaluated serious neonatal morbidity or mortality. There was no serious neonatal morbidity or mortality in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group and 1(1.08%) case in the placebo group, relative risk (RR) 0.33, confidence interval (CI) 0.01‐8.08. Although statistically there is no difference between the groups, the data should be interpreted with caution as this is a rare outcome and the confidence intervals are wide.

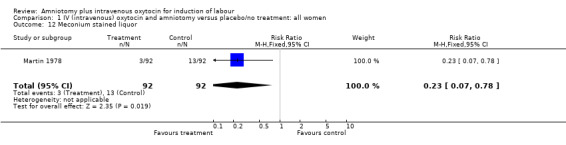

(ii) Other outcomes: A significant reduction in the amount of meconium stained liquor was found in the oxytocin and amniotomy group with 3 (3.3% ) cases in the amniotomy and oxytocin group and 13 (14.2% ) cases in the expectant group, RR 0.23, CI 0.068‐0.783. Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin versus vaginal prostaglandins ‐ all women.

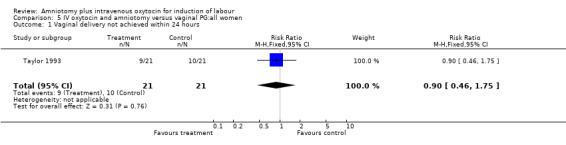

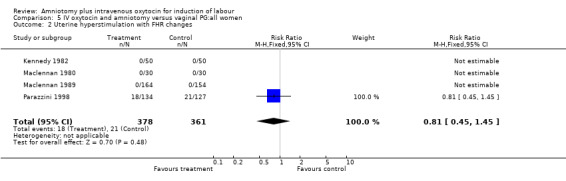

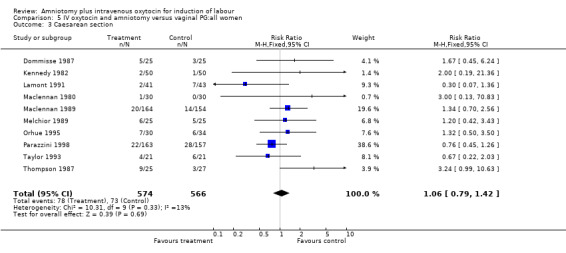

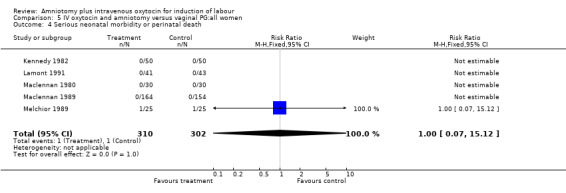

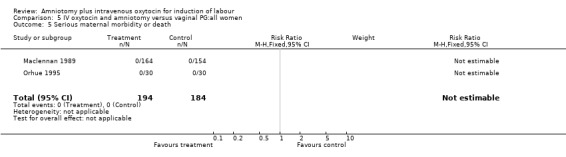

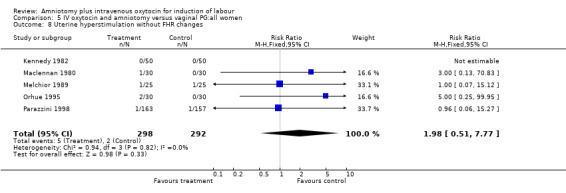

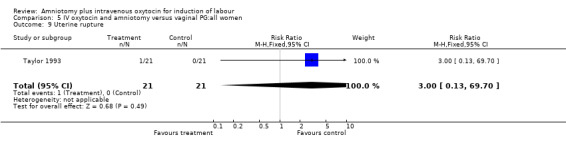

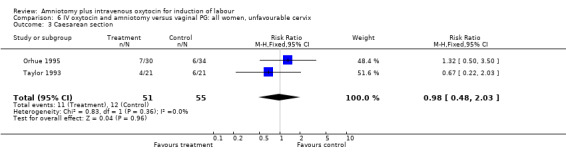

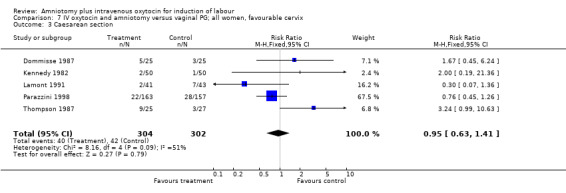

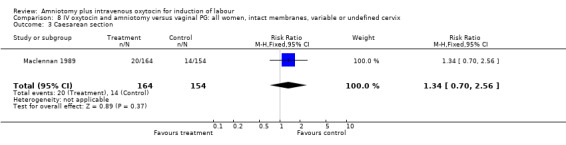

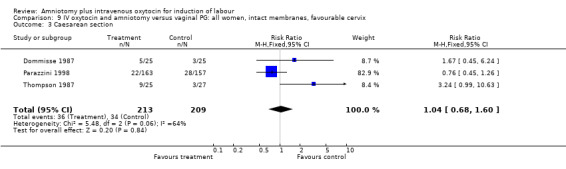

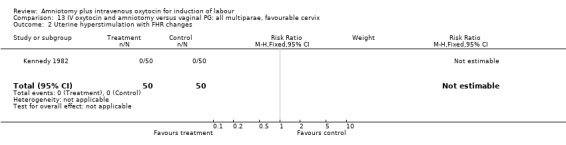

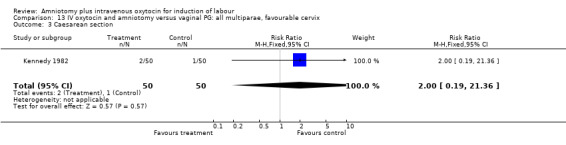

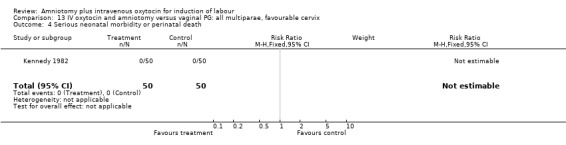

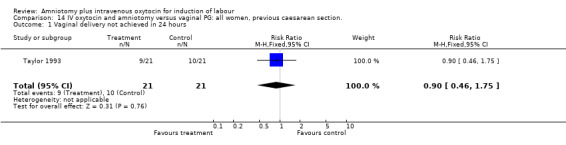

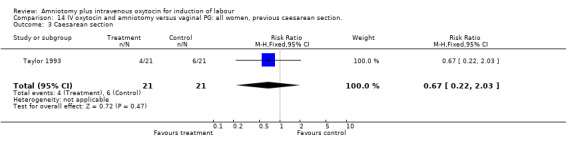

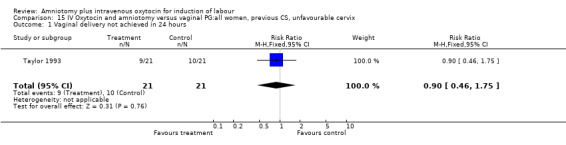

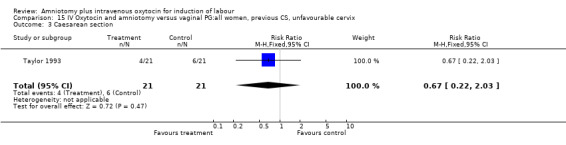

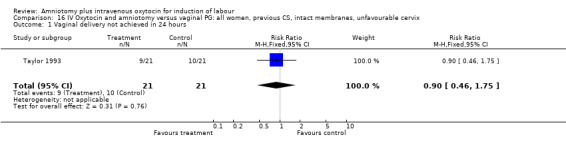

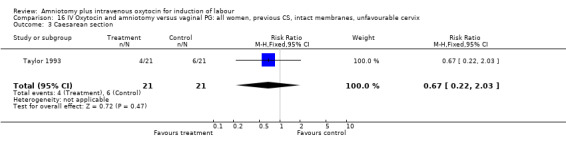

(i) Primary outcomes: One study (Taylor 1993) that included 42 participants, all of who had had previous caesarean sections, found that there was no difference in vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours. In the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group there were 9 (42.85%) women that had not delivered vaginally within 24 hours and in the vaginal prostaglandin group there were 10 (47.61%) cases, RR 0.9, CI 0.46‐1.75. Ten studies (Dommisse 1987; Kennedy 1982; Lamont 1991; Maclennan 1989; Maclennan 1980; Melchior 1989; Orhue 1995; Parazzini 1998; Taylor 1993; Thompson 1987) with 1140 participants, found no significant difference between the two groups as regards caesarean sections performed. Caesarean section was performed on 78 (13.6%) women in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group and on 73 (12.9%) women in the vaginal prostaglandin group, RR 1.06, CI 0.79‐1.42. In four studies (Kennedy 1982; Maclennan 1989; Maclennan 1980; Parazzini 1998) with 739 women, there were no differences between the two groups as regards uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes (3.4% versus 5.8%, RR 0.82, CI 0.47‐1.45). Five studies (Kennedy 1982; Lamont 1991; Maclennan 1989; Maclennan 1980; Melchior 1989), that included 612 participants reported no difference in serious neonatal morbidity or mortality in either group, RR 1, CI 0.2‐4.86. Two studies (Maclennan 1989; Orhue 1995) that included 378 women reported no serious maternal morbidity or death, RR 0.97, CI 0.06‐15.29.

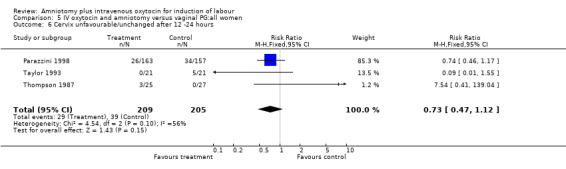

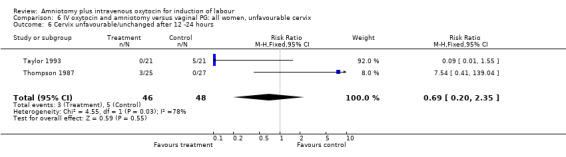

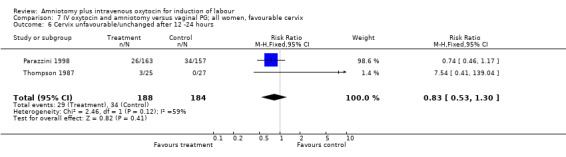

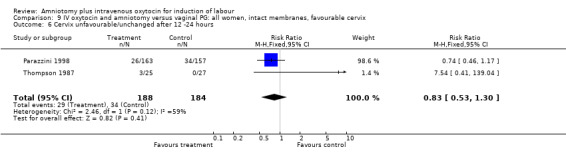

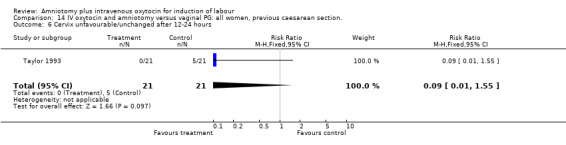

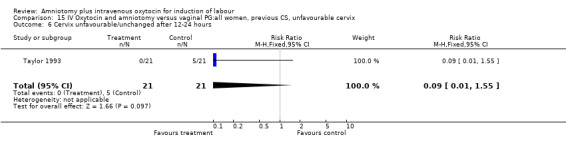

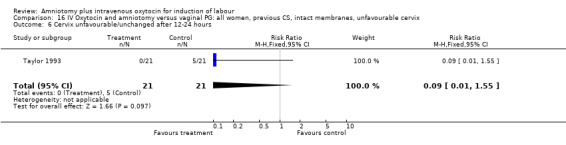

(ii) Other outcomes: Three studies (Parazzini 1998; Taylor 1993; Thompson 1987 ), that included 414 participants, found that there was no difference between the two groups when evaluated for unchanged cervical status, with 29 (13.85%) cases in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group reported as having an unchanged cervical status, compared with 39 (19.02%) cases in the vaginal prostaglandin group, RR 0.73, CI 0,47‐1.12.

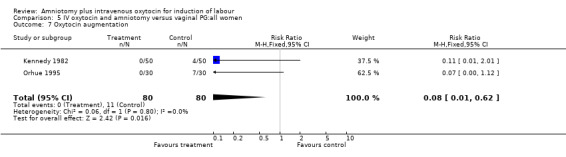

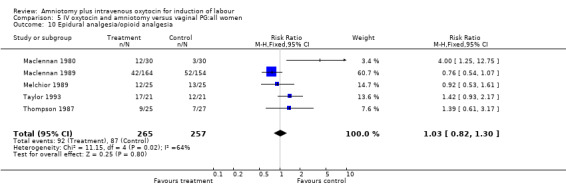

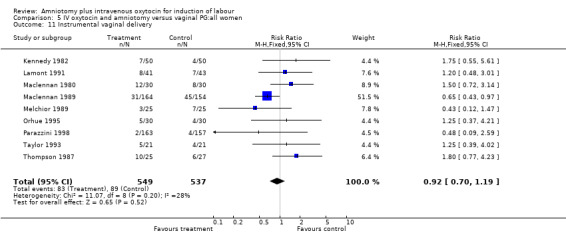

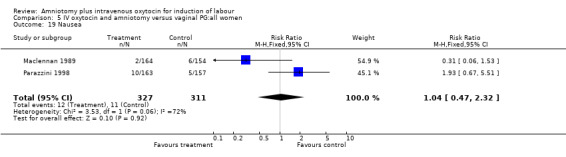

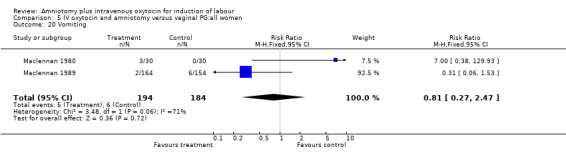

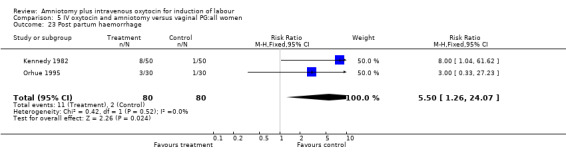

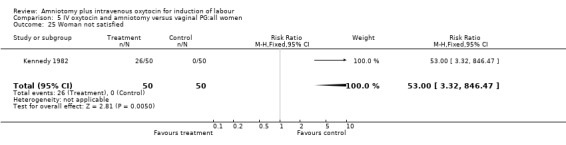

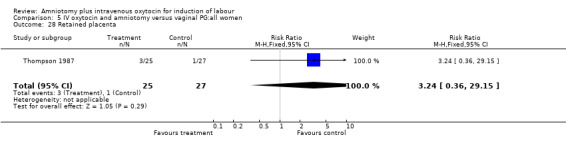

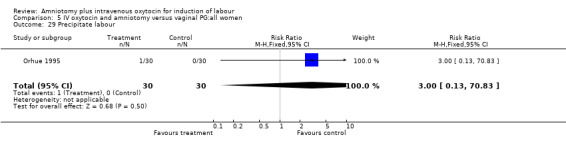

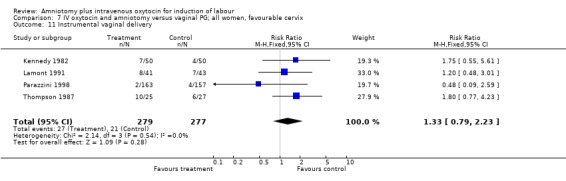

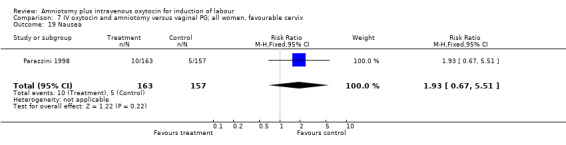

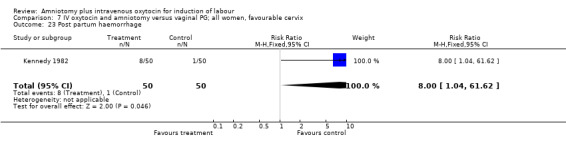

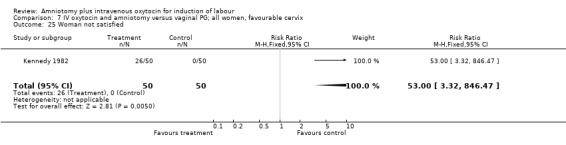

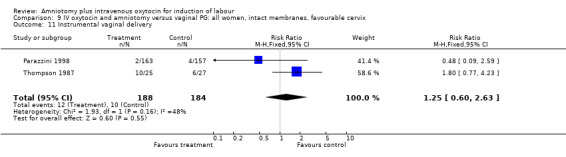

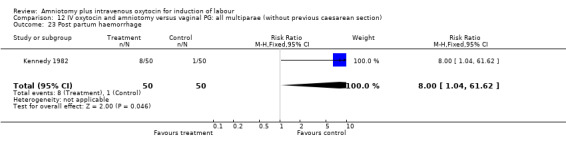

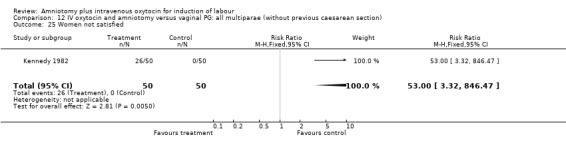

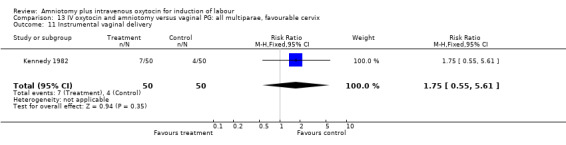

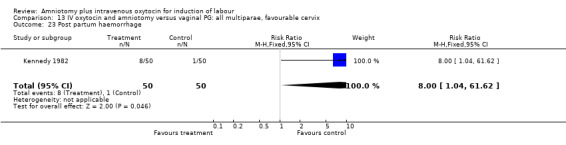

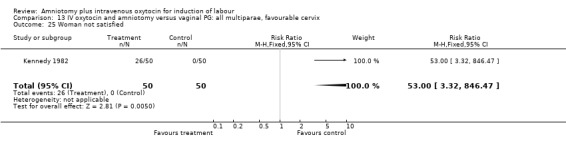

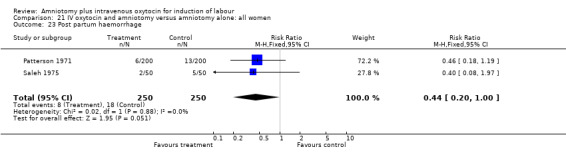

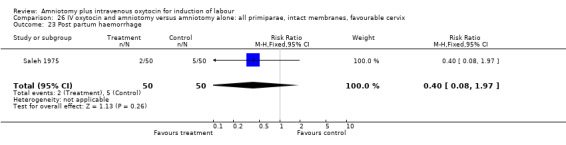

Two studies (Kennedy 1982; Orhue 1995) that included 160 women, found that there were statistically more postpartum haemorrhages in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group with 11 (13.75%) cases compared with two (2.5%) cases in the vaginal prostaglandin group, RR 5.5, CI 1.26‐24.07. One study (Kennedy 1982) of 50 parturients reported that 26 (52%) women were not satisfied with amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin compared with no women reporting dissatisfaction with vaginal prostaglandins. Although based on a single study, this is a statistically significant difference, RR 53, CI 3.32‐846. Nine studies (Kennedy 1982; Lamont 1991; Maclennan 1989; Maclennan 1980; Melchior 1989; Orhue 1995; Parazzini 1998; Taylor 1993; Thompson 1987) that included 1086 women, found that there was no difference in the number of instrumental vaginal deliveries in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group with 83 (15.12%) compared with 89(16,57%) in the vaginal prostaglandin group, RR 0.92, CI 0.70‐1.19. Two studies (Maclennan 1989; Parazzini 1998) that included 638 women, found no difference in the reporting of nausea, in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group there were 12(3.67%) cases compared with 11(3.53%) cases in the vaginal prostaglandin group, RR 1.04, CI 0.47‐2.32.

Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin versus cervical prostaglandins ‐ all women.

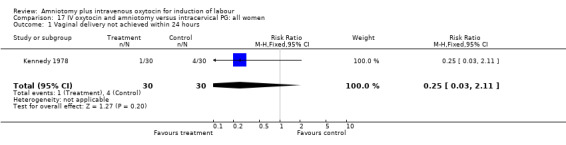

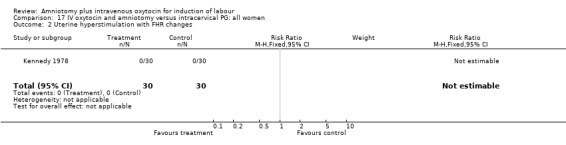

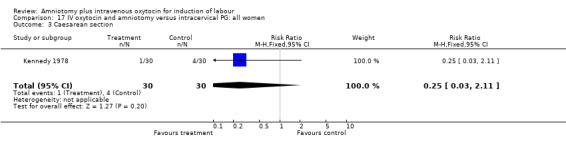

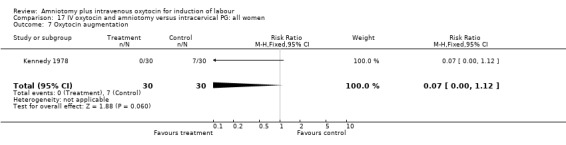

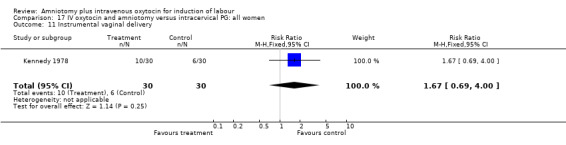

(i) Primary outcomes: All the findings are based on a single study (Kennedy 1978) with 60 participants. There was no significant difference between the two groups in women requiring caesarean section. One (3.3%) caesarean section was performed in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group compared with four (13.3%) in the cervical prostaglandin group, RR 0.25, CI 0.03‐2.1 The same study reported no cases of uterine hyperstimulation and fetal heart rate changes in either group, RR 1, CI 0.02‐48.8. The impression that there are no differences between the two groups as regards these two outcomes must be interpreted with caution as the findings are based on data from a single study, with 60 participants.

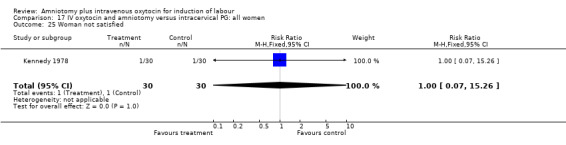

(ii) Other outcomes: The study reported the absence of meconium stained liquor in either groups. One woman in each group reported that she was not satisfied with the method of induction, RR 1, CI 0.07‐15.3.

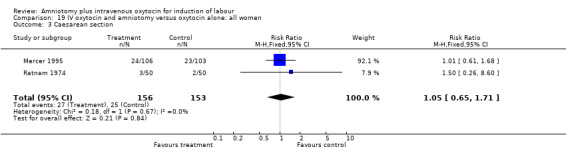

Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin versus oxytocin alone ‐ all women.

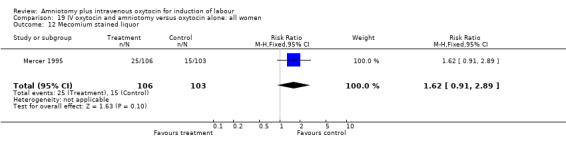

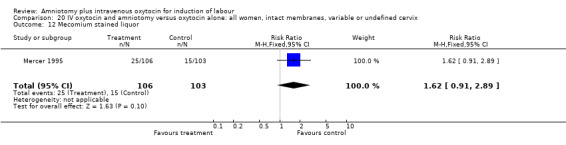

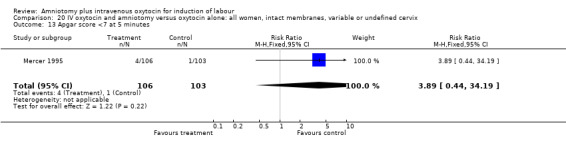

(i) Primary outcomes: Two studies (Mercer 1995; Ratnam 1974) that included 511 participants, found that there was no difference in caesarean section between these two groups with 27 (17.3%) caesarean sections performed in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group, compared with 25 (16.3%) in the oxytocin alone group, RR 1.05, CI 0.64‐1.7. (ii) Other outcomes: One study (Mercer 1995) of 209 women reported 25 (23.6%) parturients in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group had meconium stained liquor, compared with 15 (14.6%) in the oxytocin only group, RR 1.62, CI 0.91‐2.89.

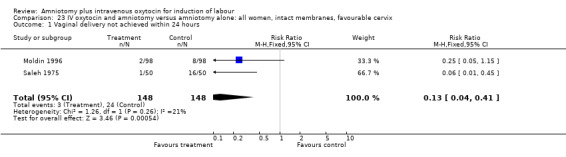

Amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin versus amniotomy alone ‐ all women.

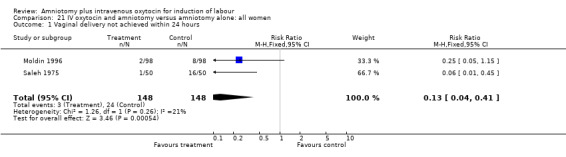

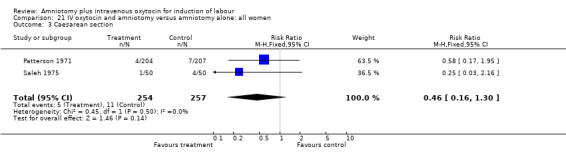

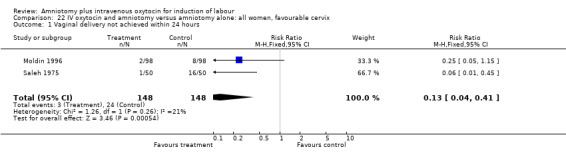

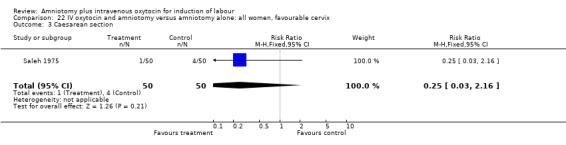

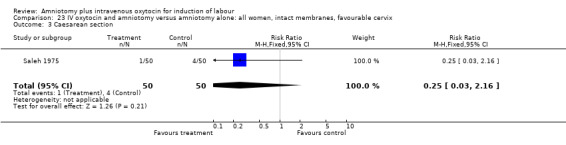

(i) Primary outcomes: Two studies (Moldin 1996; Saleh 1975), with 296 participants, found that there were significantly fewer women with vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group compared with the amniotomy alone group. There were three cases (2.1%) in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group compared to 24 cases (16.3%) in the amniotomy alone group, RR 0.125, CI 0.038‐0.406. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups as regards caesarean section (Patterson 1971; Saleh 1975) with five (1.97%) performed in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group and 11 (4.28%) in the amniotomy alone group, RR 0.45, CI 0.16‐1.3. However, the power of this study to detect meaningful differences was low.

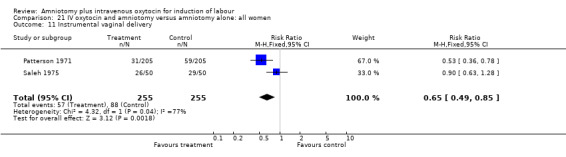

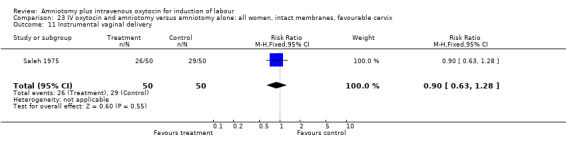

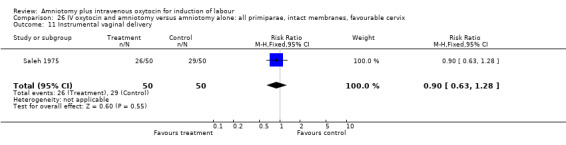

(ii) Other outcomes: Two studies (Patterson 1971; Saleh 1975) that included 510 participants found that there were statistically significantly fewer instrumental vaginal deliveries in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group 57 (22.35%) compared with 88 (34.51%) performed in the amniotomy alone group, RR 0.65, CI 0.49‐0.85.

Discussion

Despite the fact that amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin appear to be widely used for induction of labour, surprisingly little research has been done in this area. Due to the paucity of information, firm conclusions cannot be drawn on the use of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin for the induction of labour.

No single study addressed all the primary outcomes and no conclusions can be made as regards primary outcomes. Two studies that included 550 women, reported more postpartum haemorrhage in the amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin group compared with women induced with vaginal prostaglandins. One study that included 100 women, reported more women were not satisfied with amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin than vaginal prostaglandins. While interesting, the small sample sizes preclude a definitive conclusion.

This review did not evaluate comparisons between different methods of oxytocin administration and dosages and these studies have therefore been excluded (Mercer 1991; Arulkumaran 1987; Thomas 1974; Calder 1975; Chua 1991; Orhue 1993a; Orhue 1993b; Orhue 1994; Pavlou 1978; Pavlou 1978; Reid 1995; Steer 1985). It is however important to evaluate this in a separate review as the success of oxytocin induction may be dependant on the method of oxytocin administration, as it has not been standardised in the studies included in this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin have been used widely in obstetric practice, the available literature does not clearly support or refute the value of using the combination instead of the separate methods individually.

Data on the effectiveness and safety of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin are lacking. No recommendations for clinical practice can be made on the basis of this review. Cognizance however must be taken of the possibility of increased perinatal transmission of HIV following amniotomy (Biggar 1996) particularly in areas where the prevalence of HIV may be high and due to limited resources or other reasons HIV status of the woman is unknown.

Implications for research.

Despite the paucity of data, there is probably little role for further research into the use of the combination of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin as a primary method of induction. In clinical settings where resources are limited, amniotomy alone may be the favoured method of induction.

Amniotomy may also be the favoured method of induction in women not keen on pharmacological intervention or in cases where avoiding uterine stimulation may be advantageous. Under these circumstances we concur with Bricker and Luckas (Bricker 2001) that it is reasonable to recommend that further research into the method of amniotomy alone for the induction of labour is needed, and would urge researchers to evaluate this method in the context of different time intervals between the primary (amniotomy) and secondary intervention (addition of a pharmaceutical agent and with reference to this review, the use of intravenous oxytocin).

This research should include assessment of women and caregiver satisfaction and economic analysis. The suggestion from this review that oxytocin may be associated with greater risk of postpartum haemorrhage than prostaglandin, warrants further research.

[Note: The three citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 September 2009 | Amended | Search updated. Three new reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Chanrachakul 2003; Chua 1988; Selo‐Ojeme 2007) and a Published note added about the updating of this review. |

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This review will be updated by a new review team following a new protocol, which is currently being prepared.

Acknowledgements

Justus Hofmeyr, Zarko Alfirevic, Tony Kelly, Sonja Henderson

Data and analyses

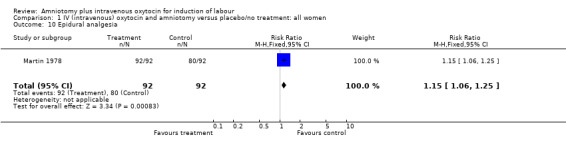

Comparison 1. IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.46, 35.11] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.08] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.06, 1.25] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.07, 0.78] |

| 25 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.77, 1.60] |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IV (intravenous) oxytocin and amniotomy versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 25 Woman not satisfied.

Comparison 5. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

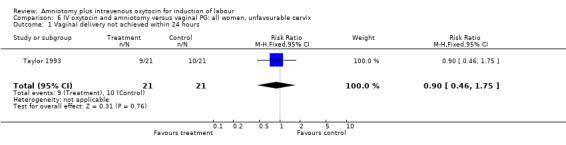

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.46, 1.75] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 4 | 739 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.45, 1.45] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 10 | 1140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.79, 1.42] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 5 | 612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours | 3 | 414 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.47, 1.12] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.01, 0.62] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 5 | 590 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.98 [0.51, 7.77] |

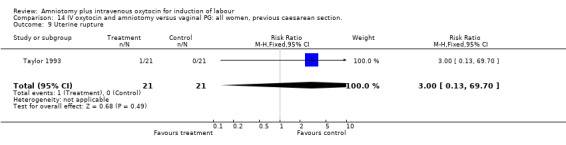

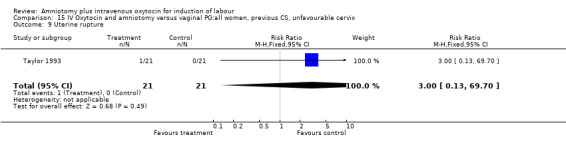

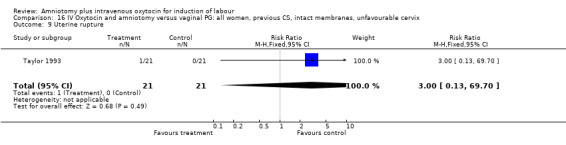

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 5 | 522 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.82, 1.30] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 9 | 1086 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.70, 1.19] |

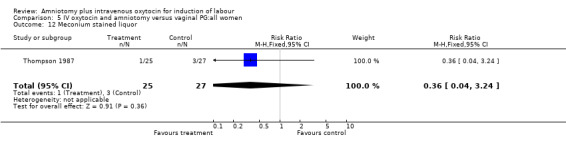

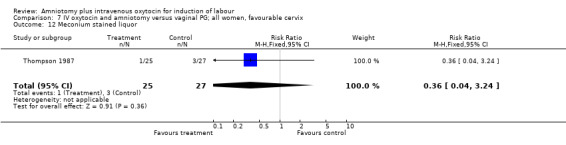

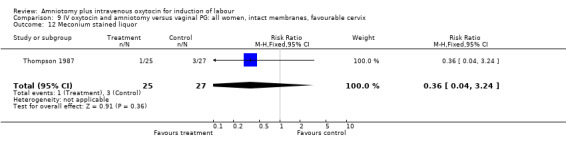

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.04, 3.24] |

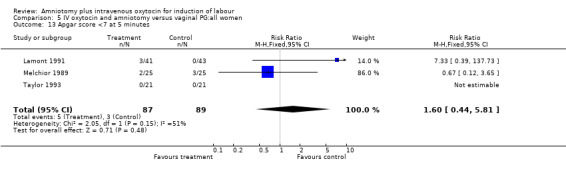

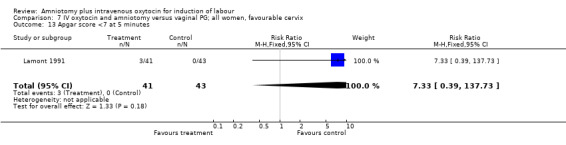

| 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 3 | 176 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.44, 5.81] |

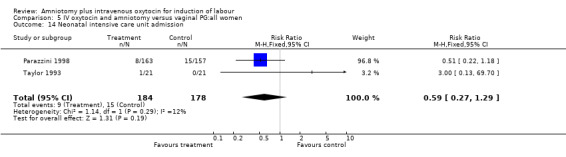

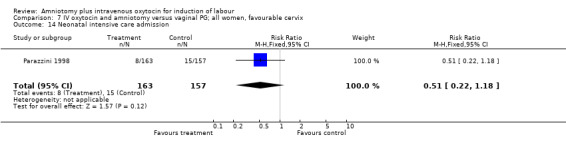

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 362 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.27, 1.29] |

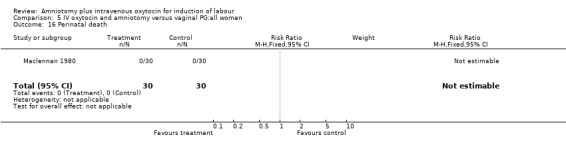

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19 Nausea | 2 | 638 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.47, 2.32] |

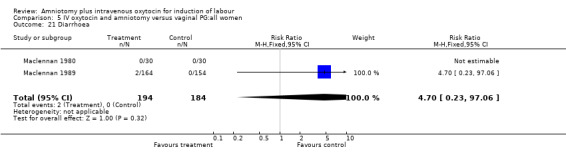

| 20 Vomiting | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.27, 2.47] |

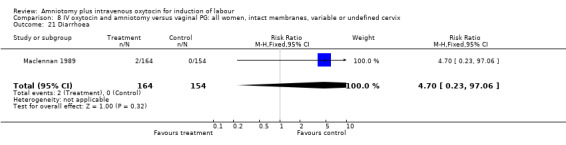

| 21 Diarrhoea | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.70 [0.23, 97.06] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.5 [1.26, 24.07] |

| 25 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 53.0 [3.32, 846.47] |

| 27 Chorioamnionitis | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

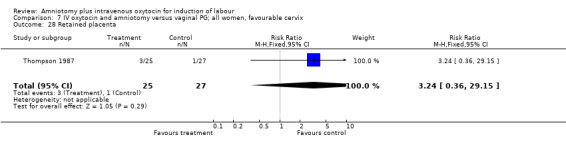

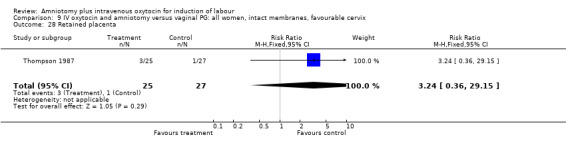

| 28 Retained placenta | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [0.36, 29.15] |

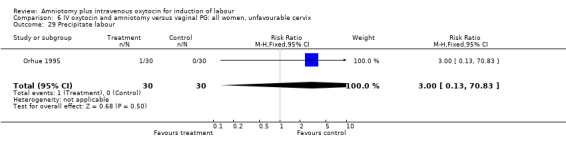

| 29 Precipitate labour | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.83] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

5.2. Analysis.

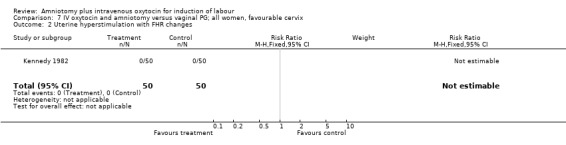

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

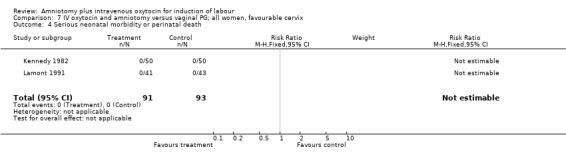

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours.

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

5.10. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

5.11. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

5.12. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

5.13. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

5.14. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

5.16. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

5.19. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 19 Nausea.

5.20. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

5.21. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

5.23. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

5.25. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 25 Woman not satisfied.

5.27. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 27 Chorioamnionitis.

5.28. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 28 Retained placenta.

5.29. Analysis.

Comparison 5 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, Outcome 29 Precipitate labour.

Comparison 6. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.46, 1.75] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 106 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.48, 2.03] |

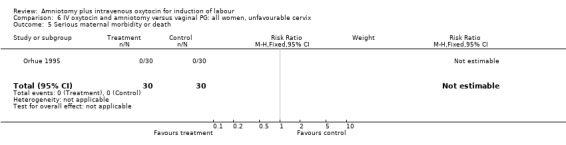

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours | 2 | 94 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.20, 2.35] |

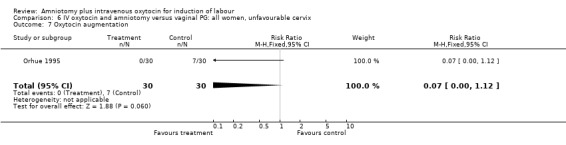

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

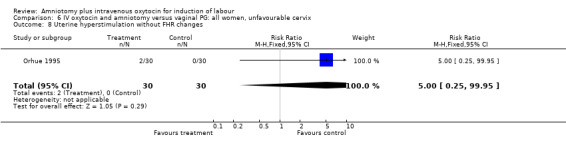

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.95] |

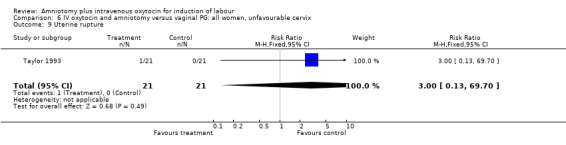

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

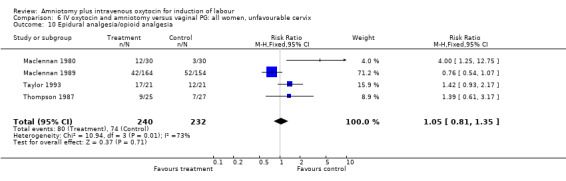

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 4 | 472 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.81, 1.35] |

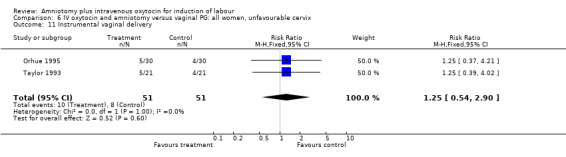

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.54, 2.90] |

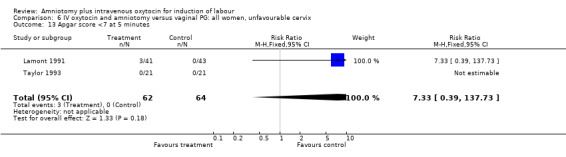

| 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.33 [0.39, 137.73] |

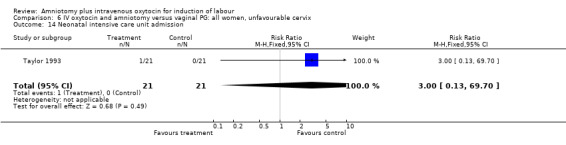

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

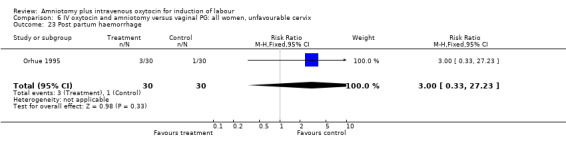

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.33, 27.23] |

| 29 Precipitate labour | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.83] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

6.10. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

6.11. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

6.13. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

6.14. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

6.23. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

6.29. Analysis.

Comparison 6 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 29 Precipitate labour.

Comparison 7. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 5 | 606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.63, 1.41] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 2 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours | 2 | 372 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.53, 1.30] |

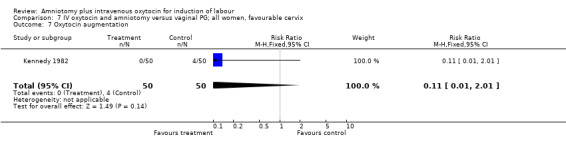

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.01] |

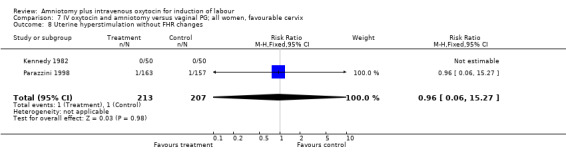

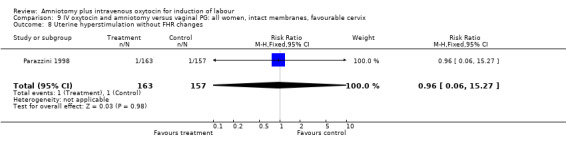

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 2 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.06, 15.27] |

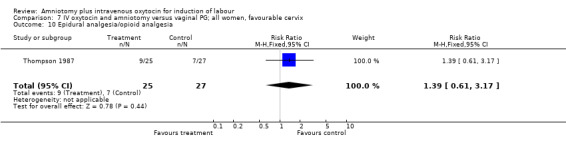

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.61, 3.17] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 4 | 556 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.79, 2.23] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.04, 3.24] |

| 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.33 [0.39, 137.73] |

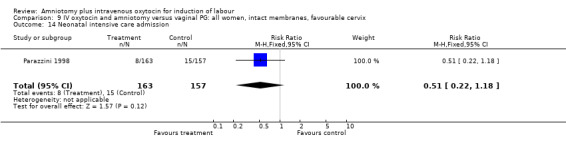

| 14 Neonatal intensive care admission | 1 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.22, 1.18] |

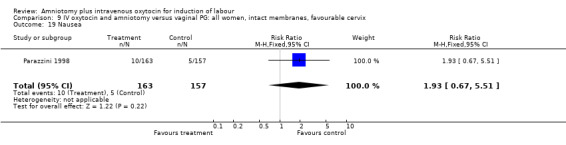

| 19 Nausea | 1 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.67, 5.51] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [1.04, 61.62] |

| 25 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 53.0 [3.32, 846.47] |

| 28 Retained placenta | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [0.36, 29.15] |

7.2. Analysis.

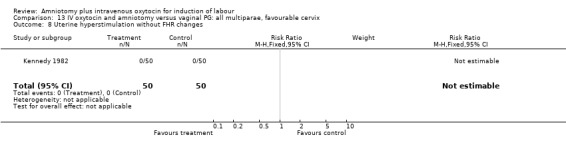

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

7.11. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

7.12. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

7.13. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

7.14. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care admission.

7.19. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 19 Nausea.

7.23. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

7.25. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 25 Woman not satisfied.

7.28. Analysis.

Comparison 7 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG; all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 28 Retained placenta.

Comparison 8. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.70, 2.56] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

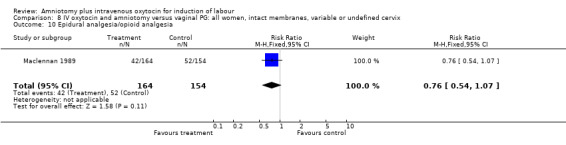

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.54, 1.07] |

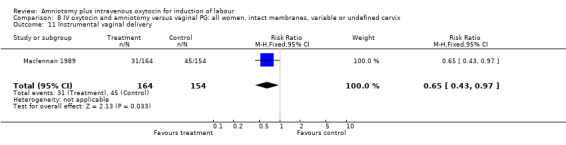

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.43, 0.97] |

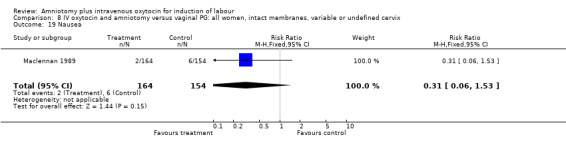

| 19 Nausea | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.06, 1.53] |

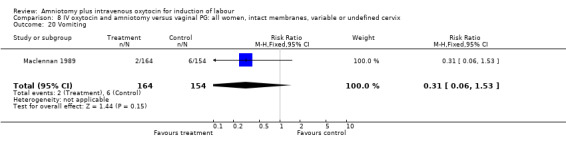

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.06, 1.53] |

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.70 [0.23, 97.06] |

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

8.10. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

8.11. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

8.19. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 19 Nausea.

8.20. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

8.21. Analysis.

Comparison 8 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 9. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 422 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.68, 1.60] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours | 2 | 372 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.53, 1.30] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.06, 15.27] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 372 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.60, 2.63] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.04, 3.24] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care admission | 1 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.22, 1.18] |

| 19 Nausea | 1 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.67, 5.51] |

| 28 Retained placenta | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [0.36, 29.15] |

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 ‐24 hours.

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

9.11. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

9.12. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

9.14. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care admission.

9.19. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 19 Nausea.

9.28. Analysis.

Comparison 9 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 28 Retained placenta.

Comparison 10. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

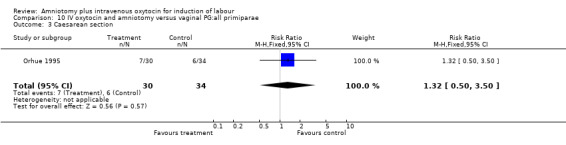

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.50, 3.50] |

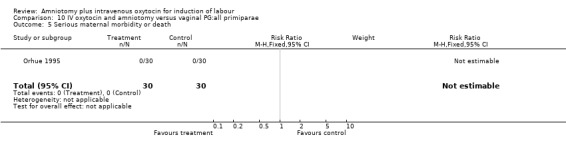

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

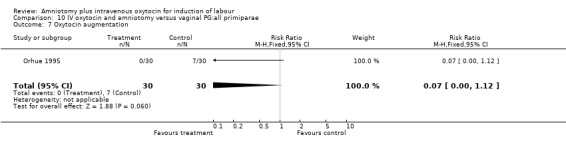

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

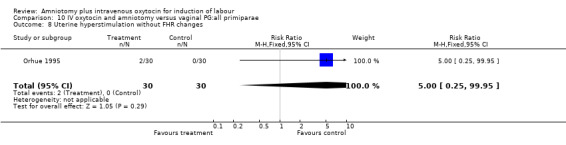

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.95] |

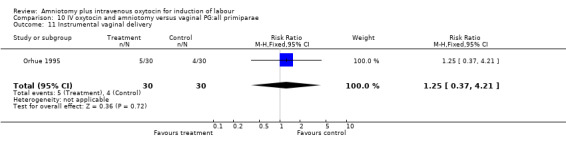

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.37, 4.21] |

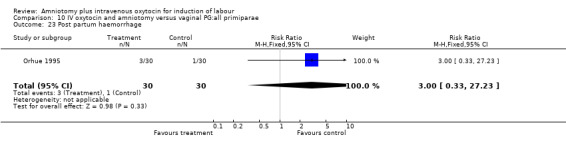

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.33, 27.23] |

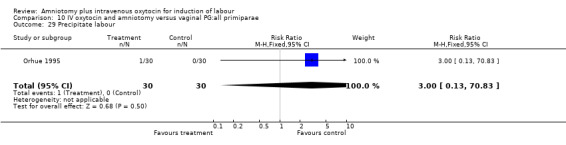

| 29 Precipitate labour | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.83] |

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

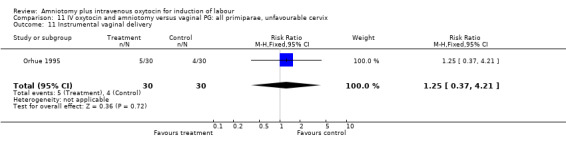

10.11. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

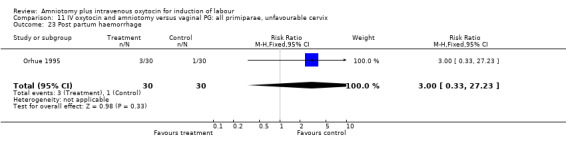

10.23. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

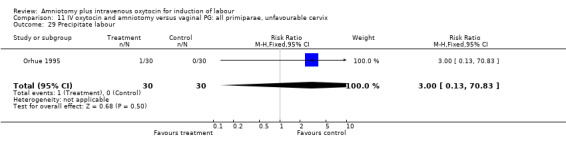

10.29. Analysis.

Comparison 10 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all primiparae, Outcome 29 Precipitate labour.

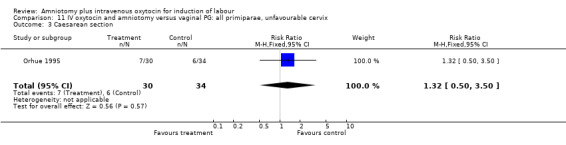

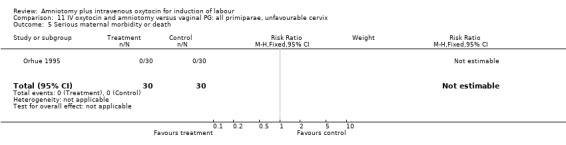

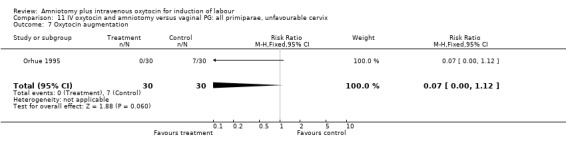

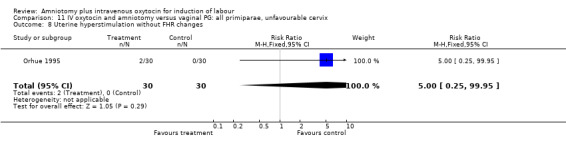

Comparison 11. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.50, 3.50] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.95] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.37, 4.21] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.33, 27.23] |

| 29 Precipitate labour | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.83] |

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

11.7. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

11.8. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

11.11. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

11.23. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

11.29. Analysis.

Comparison 11 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 29 Precipitate labour.

Comparison 12. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section).

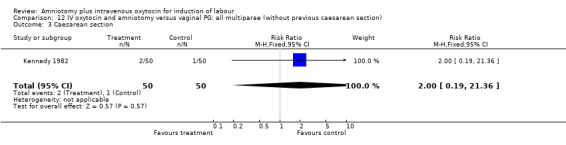

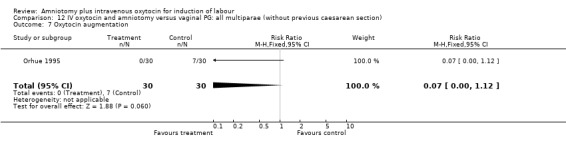

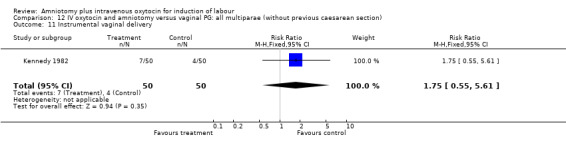

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.19, 21.36] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.75 [0.55, 5.61] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [1.04, 61.62] |

| 25 Women not satisfied | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 53.0 [3.32, 846.47] |

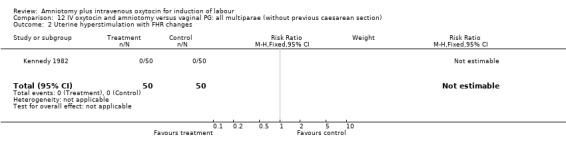

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

12.7. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

12.11. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

12.23. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

12.25. Analysis.

Comparison 12 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae (without previous caesarean section), Outcome 25 Women not satisfied.

Comparison 13. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.19, 21.36] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.75 [0.55, 5.61] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [1.04, 61.62] |

| 25 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 53.0 [3.32, 846.47] |

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

13.3. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

13.4. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death.

13.8. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

13.11. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

13.23. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

13.25. Analysis.

Comparison 13 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all multiparae, favourable cervix, Outcome 25 Woman not satisfied.

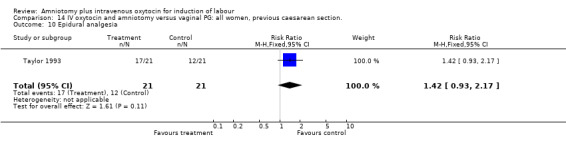

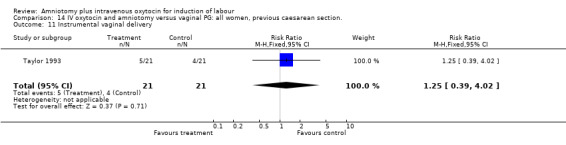

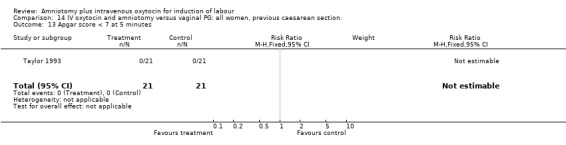

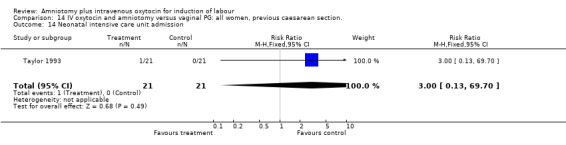

Comparison 14. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.46, 1.75] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.22, 2.03] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 1.55] |

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

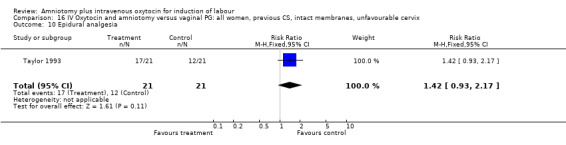

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.93, 2.17] |

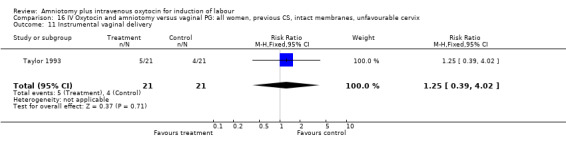

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.39, 4.02] |

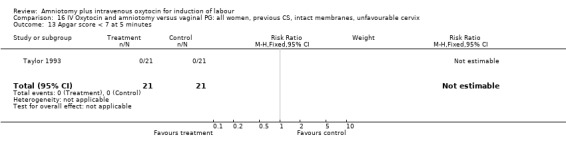

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

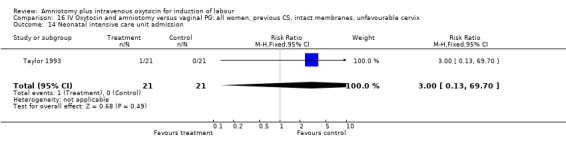

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

14.6. Analysis.

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

14.9. Analysis.

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

14.10. Analysis.

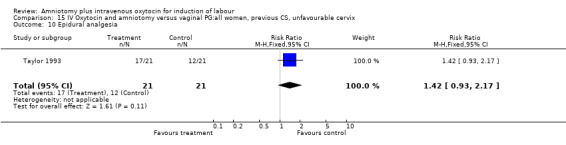

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

14.11. Analysis.

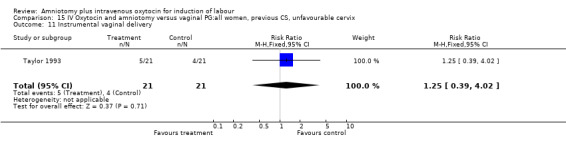

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

14.13. Analysis.

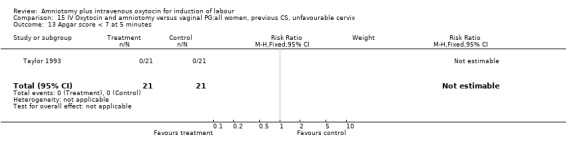

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

14.14. Analysis.

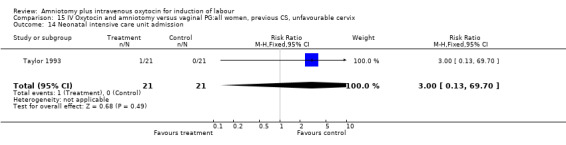

Comparison 14 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous caesarean section., Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Comparison 15. IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.46, 1.75] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.22, 2.03] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 1.55] |

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.93, 2.17] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.39, 4.02] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

15.6. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

15.9. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

15.10. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

15.11. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

15.13. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

15.14. Analysis.

Comparison 15 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG:all women, previous CS, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Comparison 16. IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.46, 1.75] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.22, 2.03] |

| 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 1.55] |

| 9 Uterine rupture | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.93, 2.17] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.39, 4.02] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

16.6. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

16.9. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Uterine rupture.

16.10. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

16.11. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

16.13. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

16.14. Analysis.

Comparison 16 IV Oxytocin and amniotomy versus vaginal PG: all women, previous CS, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Comparison 17. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.11] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.11] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.69, 4.00] |

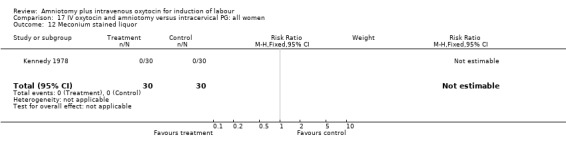

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 25 Woman not satisfied | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.26] |

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

17.2. Analysis.

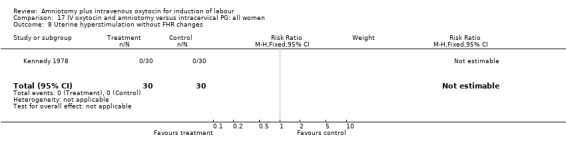

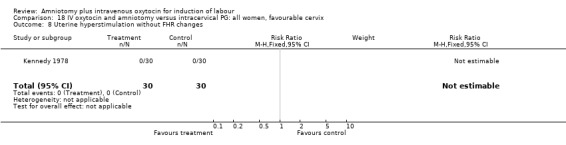

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

17.3. Analysis.

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

17.7. Analysis.

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

17.8. Analysis.

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

17.11. Analysis.

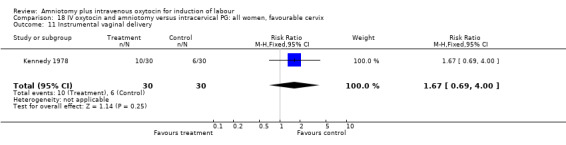

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

17.12. Analysis.

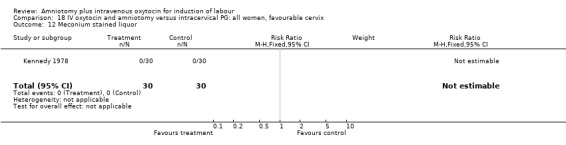

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

17.25. Analysis.

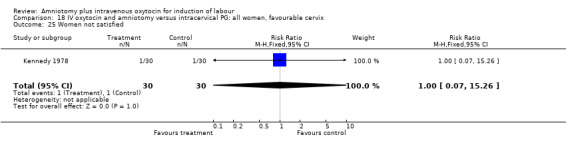

Comparison 17 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, Outcome 25 Woman not satisfied.

Comparison 18. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.11] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.11] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.12] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.69, 4.00] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 25 Women not satisfied | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.26] |

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

18.2. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

18.3. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

18.7. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

18.8. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

18.11. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

18.12. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

18.25. Analysis.

Comparison 18 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus intracervical PG: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 25 Women not satisfied.

Comparison 19. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

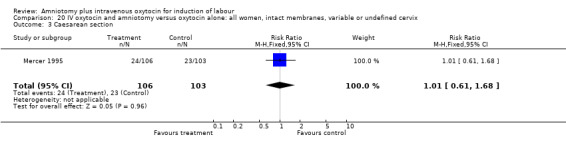

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 309 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.65, 1.71] |

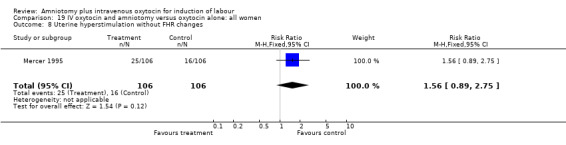

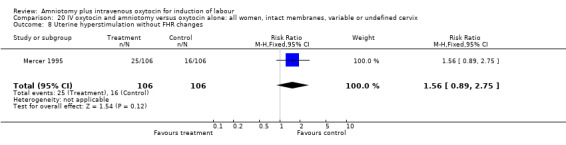

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 212 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.89, 2.75] |

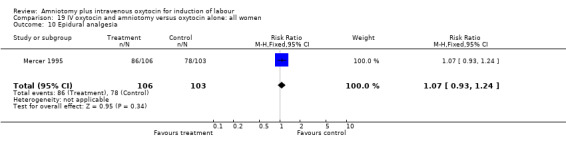

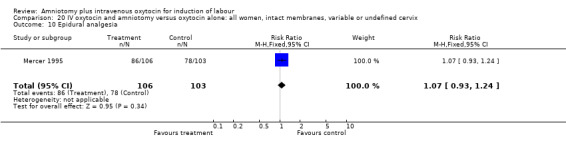

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.93, 1.24] |

| 12 Mecomium stained liquor | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.62 [0.91, 2.89] |

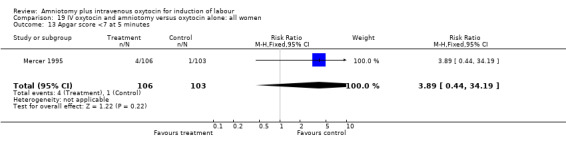

| 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.89 [0.44, 34.19] |

19.3. Analysis.

Comparison 19 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

19.8. Analysis.

Comparison 19 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

19.10. Analysis.

Comparison 19 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

19.12. Analysis.

Comparison 19 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 12 Mecomium stained liquor.

19.13. Analysis.

Comparison 19 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 20. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.61, 1.68] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 1 | 212 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.89, 2.75] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.93, 1.24] |

| 12 Mecomium stained liquor | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.62 [0.91, 2.89] |

| 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.89 [0.44, 34.19] |

20.3. Analysis.

Comparison 20 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

20.8. Analysis.

Comparison 20 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

20.10. Analysis.

Comparison 20 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

20.12. Analysis.

Comparison 20 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 12 Mecomium stained liquor.

20.13. Analysis.

Comparison 20 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus oxytocin alone: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 21. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 2 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.41] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 511 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.16, 1.30] |

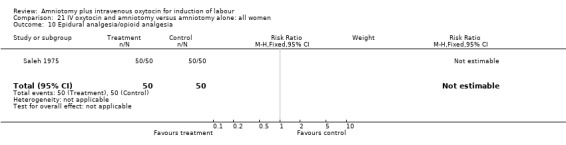

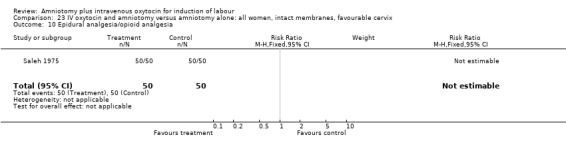

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.49, 0.85] |

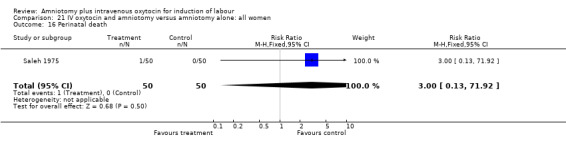

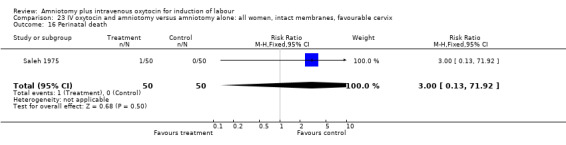

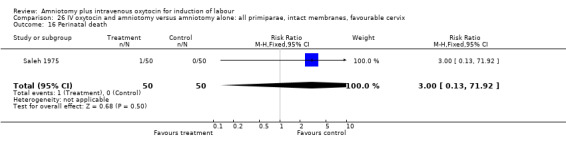

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

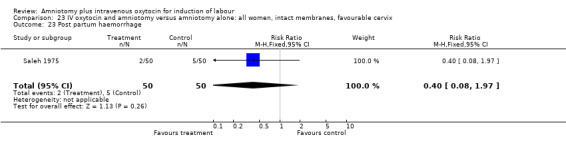

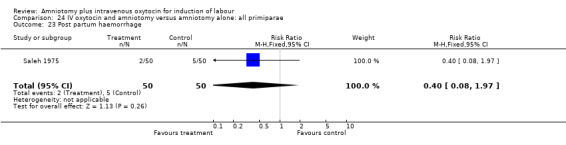

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 2 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.20, 1.00] |

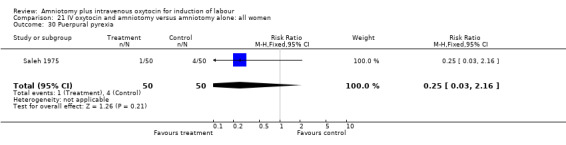

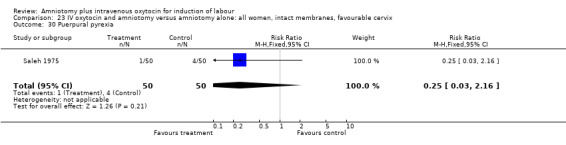

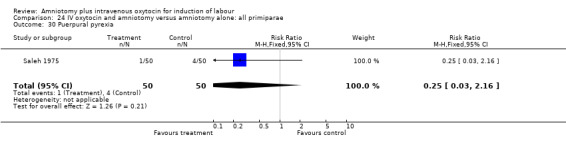

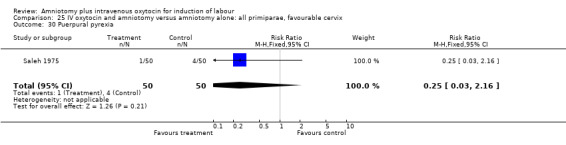

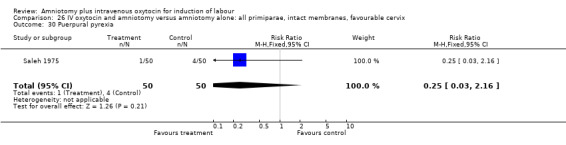

| 30 Puerpural pyrexia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

21.1. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

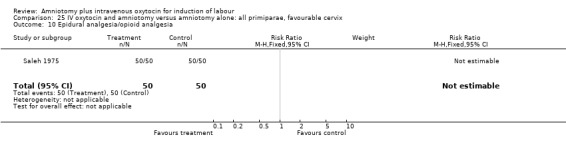

21.10. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

21.11. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

21.16. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

21.23. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

21.30. Analysis.

Comparison 21 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, Outcome 30 Puerpural pyrexia.

Comparison 22. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 2 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.41] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

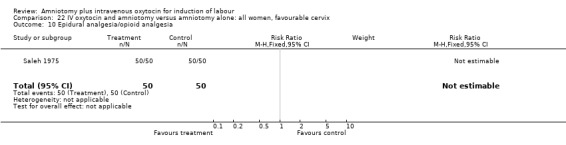

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

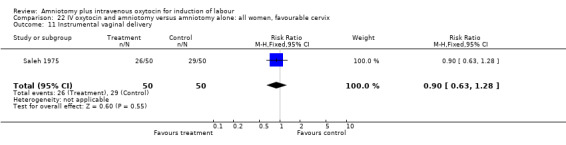

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.63, 1.28] |

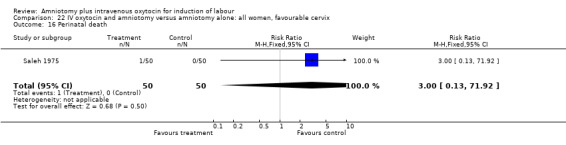

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

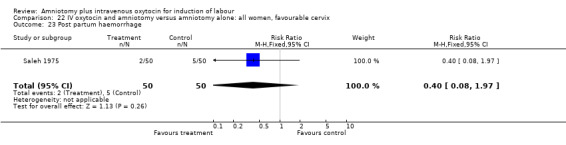

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.08, 1.97] |

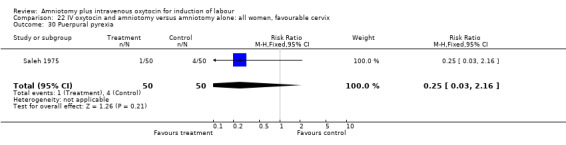

| 30 Puerpural pyrexia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

22.1. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

22.3. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

22.10. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

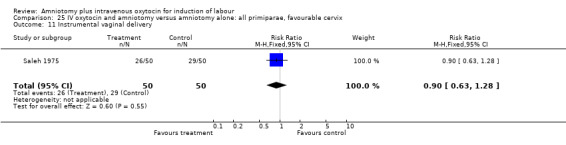

22.11. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

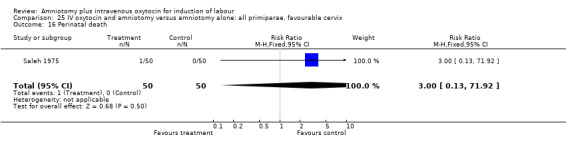

22.16. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

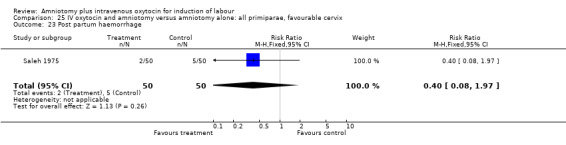

22.23. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

22.30. Analysis.

Comparison 22 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, favourable cervix, Outcome 30 Puerpural pyrexia.

Comparison 23. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 2 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.41] |

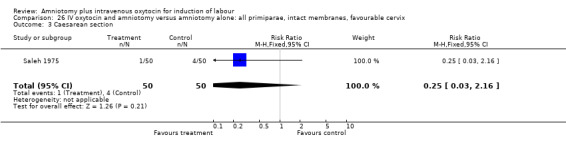

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.63, 1.28] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.08, 1.97] |

| 30 Puerpural pyrexia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

23.1. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

23.3. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

23.10. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

23.11. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

23.16. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

23.23. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

23.30. Analysis.

Comparison 23 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all women, intact membranes, favourable cervix, Outcome 30 Puerpural pyrexia.

Comparison 24. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

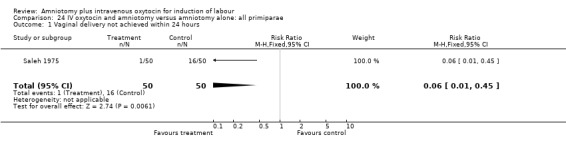

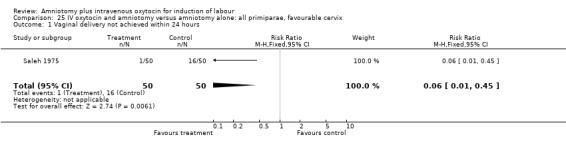

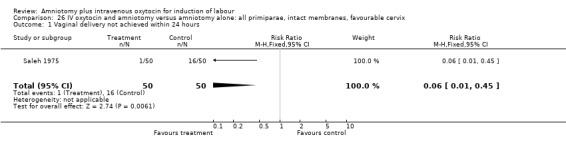

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.01, 0.45] |

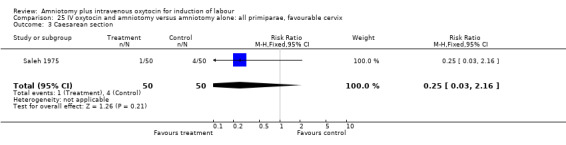

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

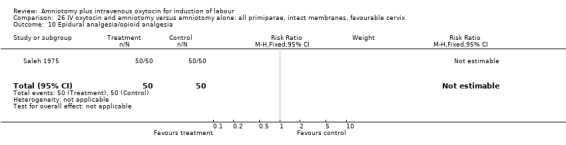

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.63, 1.28] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 23 Post partum haemorrhage | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.08, 1.97] |

| 30 Puerpural pyrexia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

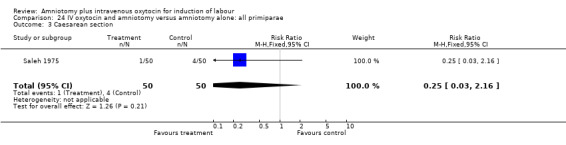

24.1. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

24.3. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

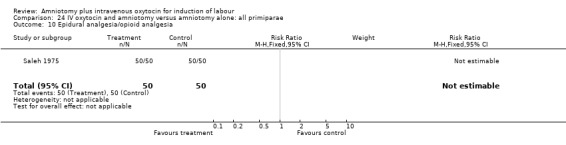

24.10. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia.

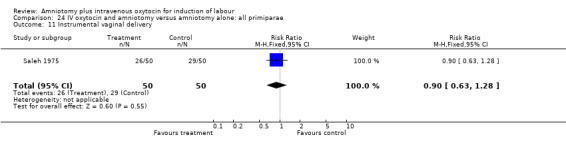

24.11. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

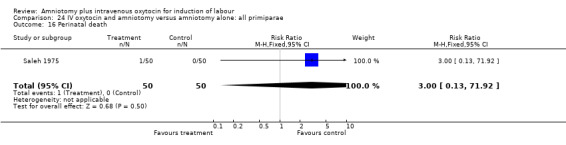

24.16. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

24.23. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 23 Post partum haemorrhage.

24.30. Analysis.

Comparison 24 IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, Outcome 30 Puerpural pyrexia.

Comparison 25. IV oxytocin and amniotomy versus amniotomy alone: all primiparae, favourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.01, 0.45] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.16] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia/opioid analgesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |