Abstract

Objective:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has significant negative effects on occupational, interpersonal, and social functioning. Supported employment is highly effective in helping people with a diagnosis of PTSD obtain and maintain competitive employment. However, less is known about the impact of supported employment on functioning in work or school, social, and interpersonal areas, as specifically related to the symptoms of PTSD.

Methods:

The Veterans Individual Placement and Support Toward Advancing Recovery study was a prospective, multisite, randomized, controlled trial that compared Individual Placement and Support (IPS) supported employment to a stepwise vocational rehabilitation involving transitional work (TW) assignments with unemployed veterans with PTSD diagnoses (n=541) at twelve VA medical centers. This analysis focuses on the PTSD-related functional outcomes over the 18-month follow-up period.

Results:

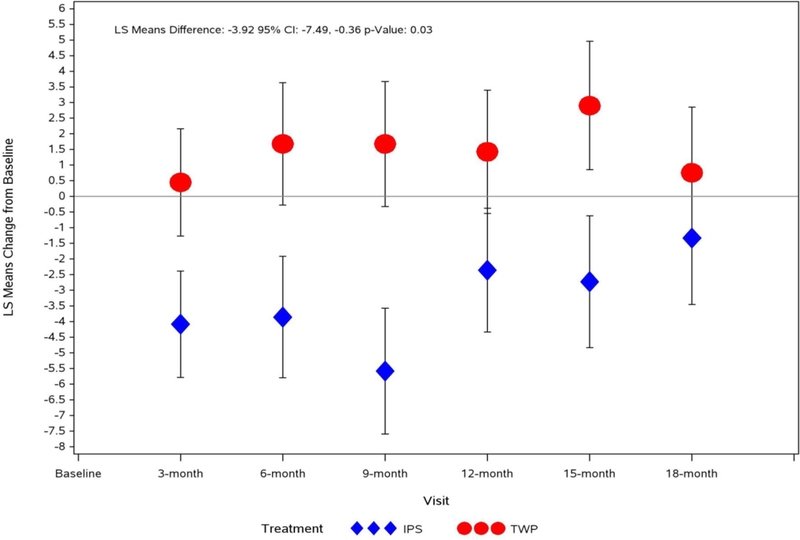

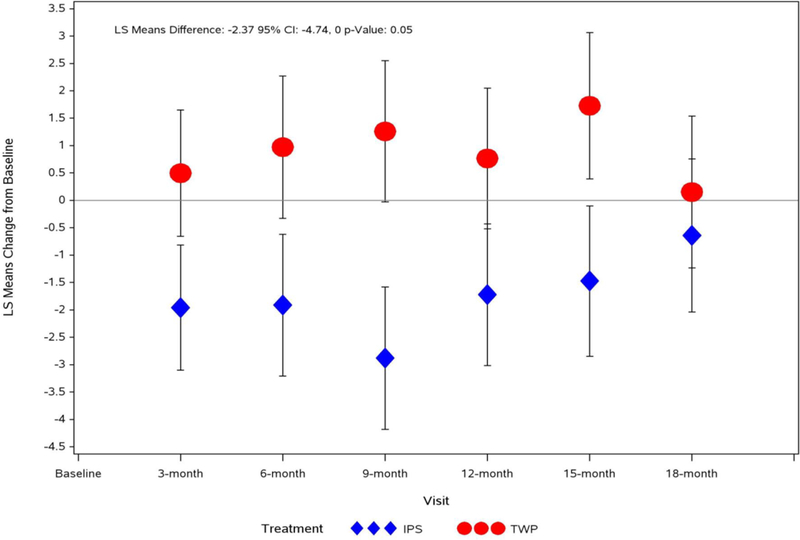

Compared to those randomized to TW, the PTSD Related Functioning Inventory (PRFI) total score significantly improved for participants randomized to IPS (−3.92; 95% CI, −7.49 to −.36; p = .03) over 18 months. When the work/school subscale of the PRFI was removed from the analysis, the IPS group continued to show significant improvements compared to the TW group on the PRFI relationship and lifestyle domains (−2.37; 95% CI, −4.74 to .00; p = .05), suggesting a positive impact of IPS beyond work/school functioning.

Conclusion:

Compared to the usual care VA vocational services for veterans with PTSD, IPS supported employment is associated with greater improvement in overall PTSD-related functioning, including occupational, interpersonal, and lifestyle domains. In addition to superior employment outcomes, IPS has a positive impact on occupational-psychosocial functioning outcomes.

Trial Registration:

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier:

Keywords: Psychosocial Functioning, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Supported Employment, Transitional Work, Employment, Veterans

Impairment in occupational-psychosocial functioning is a key component in conceptualizing or defining a mental disorder (Ro & Clark, 2009). Psychosocial functioning is generally defined as one’s capacity to productively interact and cope in the context of daily living, such as in work, school, family, social, and community settings (Ro & Clark, 2009). As is the case with many psychiatric disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with substantial reductions in psychosocial (Fang et al., 2015) and occupational functioning (Vogt et al., 2017), contributing to higher rates of unemployment and greater need for employment services (Sripada et al., 2018). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) specifies the criteria for PTSD, which include intrusive re-experiencing symptoms (such as flashbacks or nightmares), avoidance of trauma-related stimuli or reminders of the trauma, negative thoughts of feelings or cognitive distortions, and increased arousal and reactivity. PTSD can be associated with greater functional impairment as well as lower quality of life (Fang et al., 2015; Bryant et al., 2016). Surprisingly, PTSD symptom severity and level of functioning are not entirely well correlated. Some individuals can be very symptomatic, yet continue to thrive at work, in relationships, or in social settings, perhaps due to post-traumatic growth or resiliency (Averill, Averill, Kelmendi, Abdallah, & Southwick, 2018; Linley & Joseph, 2004). For many others, poor functioning can persist despite the reduction or resolution of PTSD symptoms (Bryant et al., 2016), indicating that additional support services, such as supported employment, are needed to fully restore their ability to function and succeed in life and at work.

Individual Placement and Support (IPS) supported employment is an evidence-based vocational rehabilitation service that is proven to help individuals obtain and sustain competitive employment, including people with serious mental illness (Bond, Drake, & Becker, 2008; Bond & Drake, 2014; Mueser, Drake, & Bond, 2016), PTSD (Davis et al., 2018b), and spinal cord injury (Ottomanelli, Barnett, & Goetz, 2014). IPS emphasizes an individual’s strengths, interests, and resources in reaching out to employer contacts in the community to create work opportunities that meet the individual’s and employer’s mutual needs. Once a job is obtained, IPS provides support for maintenance and/or advancement in employment as desired by the individual. Throughout these phases of job seeking, retention and advancement, IPS includes close collaboration with treating mental health clinicians to form an integrated team that serves the needs of the person (Becker, Swanson, Reese, Bond, & McLehman, 2015). This model contrasts with traditional vocational rehabilitation that involves entry-level transitional work (TW) assignments that are set-aside for individuals with mental health conditions. Transitional work is designed as a therapeutic experience for the individual to develop skills necessary to return to competitive work (Penk et al., 2010).

While numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of IPS compared to other modalities in terms of employment outcomes, less research has focused on the impact of IPS on psychosocial-occupational functioning. Two published studies showed no difference between IPS and other types of vocational rehabilitation in improving functional outcomes in people with serious mental illness (Burns et al., 2009; Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony, & Clark, 1996). However, when comparing the functional outcomes of those participants who worked to those who did not work more than minimal hours, competitive employment was associated with improved overall functioning and self-esteem, as well as more satisfaction with finances and leisure (Mueser et al., 1997; Bond et al., 2001). Thus, it appears from these studies that competitive work, rather than IPS service itself, is associated with improvements in global psychosocial functioning. To date, there are no research findings on how IPS services impact functioning in people with a diagnosis of PTSD, particularly at the level where core PTSD symptoms interface with specific occupational-psychosocial targets.

The Veterans Individual Placement and Support Toward Advancing Recovery (VIP-STAR) multisite controlled trial prospectively randomized 541 unemployed treatment-seeking veterans with PTSD to either IPS or usual-care TW services in 12 VA medical centers (Davis et al., 2018a). Across the 18-month follow-up period, IPS yielded significantly better competitive employment outcomes. Compared to the TW group, IPS participants were more likely to obtain a competitive job, hold full-time employment, and become steady workers (defined as working 50% or more of the follow-up period), thus earning more income from competitive jobs. Specifically, 39% of veterans in the IPS group became steady workers compared to 23% in the TW group (odds ratio, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.46 – 3.14; p< .001) and 69% of the IPS participants held a competitive job compared to 57% of the TW group (p=.005) (Davis et al., 2018b).

The aim of this analysis of the VIP-STAR trial is to compare the two interventions by examining the change in perceived impact of PTSD symptoms on occupational, interpersonal, and lifestyle functioning. The a priori secondary hypothesis is that, compared to the TW group, participants randomized to IPS will have a greater reduction in self-reported PTSD-Related Functioning Inventory (PRFI) scores over 18-months, indicating improvement in functioning as it relates to PTSD symptoms. The PRFI differs from general or global functioning scales, in that the self-report inventory determines the extent to which functioning difficulties are directly related to PTSD symptoms (McCaslin et al., 2016).

At the initial stages of planning the study design, the investigators theorized that IPS had the potential to lead to changes outside the narrow work domain, based on the concept that IPS involves a community-based rapid job search process and emphasis on competitive employment (Bond, 2004), which may help participants recovering from PTSD to have a more positive self-appraisal of themselves and their ability to contribute to society, causing them to re-assess the impact of PTSD symptoms on their lives, and thereby restore broken or strained relationships. We witnessed many examples of this personal transformation in a previous pilot study (Davis et al., 2012). Once working in a competitive job, the IPS participant interacts with a variety of new people in novel settings, which may facilitate integration into civilian workplace culture and expanded social networks. In contrast, the VA transitional work settings entail working in entry-level temporary jobs in VA hospital settings that may trigger a sense of continued medical or psychiatric disability in the participant. To explore these possible nonvocational outcomes in more detail, we evaluated whether the number of weeks worked in a competitive job correlate with PRFI scores at each of the 3-month follow-up visits and conducted an additional between-group comparison test of the hypothesis that, compared to the TW group, participants randomized to IPS will have a greater reduction over 18 months in relationships and lifestyle domains, i.e. PRFI scores that exclude the work/school domain. Our comparison of the two interventions in terms of the nonvocational PRFI domains may shed more light on relationship functioning and lifestyle/quality-of-life outcomes.

Method

The methods, baseline characteristics, and primary results from VIP-STAR have been detailed in two previous publications (Davis et al., 2018a, 2018b). Under IRB-approved protocol whereby all participants signed informed consent and privacy authorization, the VA Cooperative Studies Program investigators conducted a prospective, multisite trial that randomized 541 unemployed veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD to either IPS (n=271) versus TW (n=270) services and followed the participants for 18 months. Participants were enrolled between December 2013 and April 2015 at twelve VA medical centers.

Eligibility Criteria

Consenting veterans who were unemployed and interested in competitive work, age 18–65 years, eligible for VA usual-care TW assignments, and diagnosed with PTSD (lifetime) as confirmed by Clinician Administered PTSD Scale DSM-IV (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) were included in the study. Veterans were excluded if they had a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, dementia, or a severe cognitive disorder; current suicidal (Sheehan Suicidality Tracking Scale; Coric, Stock, Pultz, Marcuc, & Sheehan, 2009) or homicidal ideation; were unlikely to complete the study due to expected deployment, incarceration, relocation or long-term hospitalization; or were participating in another vocational intervention study.

Randomization

Utilizing a permuted block design of randomly varying block sizes that was stratified by site, participants were randomized to either IPS or TW and followed for 18 months. In keeping with the principles of intent-to-treat, participants who were randomized but then subsequently declined IPS or TW vocational services, TW assignments, job interviews, and/or job offers were encouraged to remain in the study for follow-up assessments. All available data from all randomized participants were included in the analyses.

Once randomized, the participants, assessors and providers were aware of the treatment assignment. Expectation bias was minimized by a fundamental concept stressed to all members of the research team and treatment teams that the study was being conducted for treatments that were in clinical equipoise, i.e. there was a genuine uncertainty over whether one treatment/intervention would be more beneficial than the other. During the informed consent stage, the two interventions were presented to the prospective participant as having different treatment strategies (IPS vs TW) that shared a similar long-term goal of helping veterans obtain and maintain competitive employment and that the purpose of the study was to see which treatment was more beneficial. The prospective participants were not aware of the hypotheses to be tested. In addition, the investigators and the clinical research coordinators who collected the outcomes were not the individuals whom delivered the treatments. Finally, the outcomes were either objective (i.e. employment details rather than rating scales) or self-report (PRFI) which minimizes the chance that an investigator or treatment provider can influence outcome scores.

Interventions and Assessments

Details of both interventions, fidelity monitoring, the training of IPS employment specialists, processes for the collection of employment outcomes, and description of all assessments for the full study are provided by Davis et al. (2018a, 2018b). Briefly, IPS provides person-centered services that includes vocational assessment; individualized job search and job development that is consistent with the participant’s preferences, skills, and abilities; job coaching and advocacy; care coordination within the PTSD treatment team; disability benefits counseling; and open-ended follow-along supports. TW involves vocational assessment followed by a set-aside, pre-employment, brokered, time-limited assignment in a non-competitive, minimum-wage activity, such as maintenance, housekeeping, or laundry services. During the TW assignment, the participant receives some guidance for competitive job searches, but, the vocational rehabilitation specialist does not engage in community-based job development activities or provide long-term follow-up after the first competitive job is obtained or TW ends. Using the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale (Bond, Becker, Drake, & Vogler, 1997) sites were rated by a trained fidelity monitor to document the degree of adherence to the respective vocational rehabilitation models, and guide additional training when needed. The fidelity scale differentiates between good implementation (66–75) fair implementation (56–65), and not supported employment (55 and below; Bond et al., 1997). IPS services scored in the good implementation range by the second fidelity visit, and most sites maintained this level; two sites achieved this level after additional training. As expected, TW services scored considerably below the 55 rating, with an average of 26–32, indicating the services were distinctly different than those offered by supported employment.

During the 18-month follow-up, participants were instructed to maintain a study-formatted Employment Calendar Diary and to bring this employment diary with copies of pay/tax forms to follow-up visits. Employment outcomes included weekly accounts of whether the participant work for pay (yes/no/unknown); type of work (TW/competitive/other); type of job(s), number of days and hours worked; and gross income earned and sources. Veterans’ self-report of the job title, hours, start and end dates, and accompanying documentation such as pay stubs/documents were used to validate employment. If the research coordinator had any doubt verifying whether employment met criteria for a competitive job, an adjudication process was invoked that provided an independent outcomes evaluation by a blinded assessor

Measurement of Functional Outcome

Posttraumatic Stress Related Functioning Inventory (PRFI; McCaslin et al., 2016) was collected at baseline and every three months during the 18-month follow-up. The PRFI is a self-report scale that measures the extent to which PTSD symptoms interfere with functioning in three areas: work/school, relationships, and lifestyle. Originally developed to align with the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, the PRFI was revised for this study to include the three new symptoms added to the DSM-5 PTSD diagnosis, yielding a total of 33 PRFI items. The PRFI preamble states: “The following questions ask how your symptoms have impacted your quality of life in the following areas: work or school, relationships, and lifestyle. Please choose the answer that best corresponds to each statement. We ask that you think about your life in the past 4 weeks when answering each question.”

The impact of specific PTSD symptom clusters as well as items that assess the total impact of the symptoms on each area of functioning are included in the PRFI. Each domain is made up of 11 items divided into two subscales: Symptom Cluster Impact which separately assesses the impact of re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal symptom clusters on each domain of functioning; and Total Symptom Impact which includes items that address the functional impact of all four clusters of PTSD symptoms taken together on relevant real-world examples of the domain (i.e., “Taken together, these symptoms ….”). Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Only the first 32 items are scored and item 33 provides a free text space for the individual to provide additional information about functional difficulties. Total PRFI scores are derived by summing all items, except the last free-text item (range 0 to 128). Total subscale scores range from 0 to 44 (work and school functioning), 0 to 44 (relationship functioning), and 0 to 40 (lifestyle), with higher scores indicating worse functioning. Total Symptom Cluster Impact scores within each domain are derived by summing the first 6 items in each domain (work and school functioning, relationship functioning i.e., “ability to form new relationships and maintain old relationships”, and lifestyle i.e., “quality of life, including living situation, ability to engage in enjoyable activities”). Total Symptom Impact subscale scores within each domain are derived by summing remaining 4 to 5 items in each domain.

Test-retest reliability for the DSM-IV version of PRFI subscales from baseline to 12 months ranged from .71 to .75. Internal consistency ranged from .90 to .96, with only one exception, the total symptom impact on lifestyle was lower at .80 due to the items pertaining to legal and housing problems that were less common in the sample. There is evidence for validity of the scale based on the pattern of correlations with measures of symptoms of PTSD, depression, alcohol, and substance use, as well as measures of quality of life (McCaslin et al., 2016).

Analysis

Regardless of adherence to the intervention, all randomized participants were included in the analyses (intent-to-treat approach). Between-group analyses of PRFI scores overall and of PRFI scores with the work/school domain excluded were conducted by using longitudinal repeated measures mixed effects model adjusted for participating medical center and using an unstructured covariance matrix. The outcome variable in the model was the change in PRFI score at each follow-up time point relative to baseline; baseline score was used as a covariate in the model. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.3. The repeated measures longitudinal analysis used can accommodate incomplete data. To explore whether competitive employment was associated with improvement in the PRFI, correlation analyses were conducted between the PRFI scores at each follow-up and the number of weeks of competitive employment in the previous 3 months within each condition.

Results

Participant Flow

Of the 1268 veterans who were approached or expressed interest in the study, 605 consented to participate, 541 were randomized (IPS n=271 vs TW n=270), and 437 (80.8%) completed the 18-month study assessments (IPS n=218 vs TW n=219). Participants remained in the study for 77.2 (SD ± 17) weeks on average, with no difference between groups.

Participant Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

The two groups were balanced on demographic (age, race, ethnicity, marital status, education), presence of co-occurring mental illness or substance use disorder, duration or severity of PTSD, and past employment-related variables at baseline (See Tables 1 and 2). The participants were on average 42.2 (SD = 10.9) years of age. The sample consisted of 81.7% males, 50.6% Whites, 41.6% African-Americans, and 16.6% of Hispanic ethnicity. Participants were married (32%), divorced (29.8%), or never married (25%). The majority had some college (41.4%) and adequate current housing (84.3%). Concurrent diagnoses for participants included PTSD (100%), major depression (31.4%), agoraphobia (22.7%), and social anxiety (14.6%). At baseline, 24.4% of participants met criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence and 16.1% for substance use/dependence in the past year. The chronicity of PTSD was on average 13.3 (SD = 11.4) years.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics

| Variable | IPS (n = 271) |

TW (n = 270) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 224 | 82.7 | 218 | 80.7 |

| Female | 47 | 17.3 | 52 | 19.3 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 138 | 50.9 | 136 | 50.4 |

| African-American | 115 | 42.4 | 110 | 40.7 |

| Other | 32 | 11.8 | 36 | 13.3 |

| Spanish, Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity | 43 | 15.9 | 47 | 17.4 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 89 | 32.8 | 84 | 31.1 |

| Divorced | 82 | 30.3 | 79 | 29.3 |

| Never married | 68 | 25.1 | 67 | 24.8 |

| Separated/Cohabitating/Widowed | 32 | 11.8 | 40 | 14.8 |

| Education | ||||

| High school diploma or less | 54 | 20.0 | 43 | 15.9 |

| Some college credit | 106 | 39.1 | 118 | 43.7 |

| Associate’s Degree | 55 | 20.3 | 35 | 13.0 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 40 | 14.8 | 57 | 21.1 |

| Master’s or Doctoral Degree | 16 | 5.9 | 17 | 6.3 |

| Branch of Service | ||||

| Army | 158 | 58.3 | 171 | 63.3 |

| Navy | 50 | 18.5 | 49 | 18.1 |

| Marine Corp | 52 | 19.2 | 32 | 11.9 |

| Air Force | 22 | 8.1 | 25 | 9.3 |

| National Guard, Coast Guard, NOAA | 17 | 6.3 | 23 | 8.5 |

| Period of Service | ||||

| Vietnam | 31 | 11.4 | 26 | 9.6 |

| 1975–1990 | 83 | 30.6 | 78 | 28.9 |

| Persian Gulf War | 50 | 18.5 | 56 | 20.7 |

| March 1991-August 2001 | 82 | 30.3 | 84 | 31.1 |

| Post 9–11-2001 | 162 | 59.8 | 162 | 60 |

| Served in Combat Zone | 191 | 70.5 | 198 | 73.3 |

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age (years) | 42.5 | 10.7 | 41.9 | 11.2 |

| Length of past military service (years) | 8.0 | 6.3 | 8.5 | 6.6 |

| Length of current unemployment (years) | 2.7 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4.1 |

| Duration of longest job in lifetime (years) | 8.3 | 5.8 | 8.7 | 6.4 |

Table 2.

Psychiatric and Functional Variables

| Variable | IPS (n = 271) |

TW (n = 270) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Primary Type of Trauma | ||||

| Combat-related (non-sexual) | 155 | 57.2 | 164 | 60.7 |

| Military sexual trauma | 53 | 19.6 | 40 | 14.8 |

| Other Military-related | 37 | 13.7 | 34 | 12.6 |

| Civilian adult trauma | 12 | 4.4 | 16 | 5.9 |

| Childhood trauma | 14 | 5.2 | 16 | 6.0 |

| PCL-5 at current diagnostic threshold (≥33) | 209 | 77.1 | 204 | 75.6 |

| PCL-5 current severity, range | ||||

| Very mild (0–18) | 14 | 5.2 | 20 | 7.4 |

| Mild (19–37) | 64 | 23.6 | 60 | 22.2 |

| Moderate (38–59) | 128 | 47.2 | 138 | 51.1 |

| Severe (60–80) | 63 | 23.2 | 49 | 18.1 |

| MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview | ||||

| Major Depression (past) | 183 | 67.5 | 173 | 64.1 |

| Major Depression (current) | 87 | 32.1 | 83 | 30.7 |

| Agoraphobia (current) | 64 | 23.6 | 59 | 21.9 |

| Panic (lifetime) | 66 | 24.4 | 62 | 23 |

| Panic (current) | 37 | 13.7 | 33 | 12.2 |

| Social Anxiety (current) | 35 | 12.9 | 28 | 10.4 |

| Obsessive Compulsive (current) | 22 | 8.1 | 19 | 7 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder (past year) | 54 | 19.9 | 78 | 28.9 |

| Non-alcohol Use Disorder (past year) | 47 | 17.3 | 40 | 14.8 |

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Duration of PTSD (years) | 13.3 | 11.6 | 13.4 | 11.2 |

| Total CAPS-IV (lifetime) | 84.1 | 18.9 | 84.8 | 18.3 |

| PCL-5 past month (current) | 52.7 | 10.9 | 52.4 | 11.2 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Related Functioning Inventory | 96.5 | 29.4 | 96.4 | 29.9 |

Note. CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL = PTSD Checklist

Overall, the participants had been unemployed for an average of 2.8 years (SD = 3.8). Approximately two-thirds of participants had not held a job (32.5%) or had held only one job (34.4%) in the past three years. In addition, about two-thirds of participants received VA service-connected disability compensation.

PRFI Baseline Assessments and Outcomes

At baseline, the two groups were similar in total PRFI scores: IPS group mean 96.5 (SD ± 29.4) versus TW group mean 96.4 (SD ± 29.9). The PRFI range was identical between groups (30 to 160). Scores on the subscales were also similar, ranging from a 0.1 to 0.2 nonsignificant difference between the groups at baseline. In the subscale for relationships, the IPS group mean score was 31.5 (SD ± 11.2) and TW was 31.3 (SD ± 11.6); in the subscale for lifestyle, the IPS group mean score was 29.5 (SD ± 8.8) and TW was 29.6 (SD ± 9.1).

Over the 18-month follow-up period, the IPS group had a significant reduction in their total PRFI scores compared to the TW group (−3.92; 95% CI, −7.49 to −.36; p = .03; Figure 1). When the work/school domain was omitted, the IPS group had a significant reduction on the PRFI scores for relationships and lifestyle domains than the TW group (−2.37; 95% CI, −4.74 to .00; p = .05; Figure 2; Table 3). Within each treatment group, there were no associations between PRFI scores at each follow-up and the number of weeks worked in competitive employment in the previous 3 months (see Table 3).

Figure 1.

Change from Baseline in Posttraumatic Stress Related Functioning Inventory Total Score

Note. PRFI decrease in scores indicates less impact of PTSD symptoms on functioning and overall improvement in functioning.

Figure 2.

Change from Baseline in Posttraumatic Stress Related Functioning Inventory for Relationship and Lifestyle Domains and without Work-School Domain

Note. PRFI decrease in scores indicates less impact of PTSD symptoms on functioning and overall improvement in functioning.

Table 3.

PTSD-Related Functioning Inventory and PTSD Checklist Outcomes

| Longitudinal Analysis of PRFI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Points (months) | LSMeans: IPS | LSMeans: TW | ||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |||

| 3 | −4.08 | −7.42 | −0.74 | 0.45 | −2.91 | 3.81 |

| 6 | −3.85 | −7.67 | −0.04 | 1.68 | −2.16 | 5.52 |

| 9 | −5.58 | −9.53 | −1.63 | 1.68 | −2.24 | 5.60 |

| 12 | −2.35 | −6.25 | 1.54 | 1.43 | −2.44 | 5.29 |

| 15 | −2.72 | −6.87 | 1.42 | 2.91 | −1.13 | 6.94 |

| 18 | −1.33 | −5.49 | 2.82 | 0.76 | −3.37 | 4.88 |

| LSMeans Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| PRFI Total Overall | −3.92 | −7.49 | −0.36 | 0.03 | ||

| Longitudinal Analysis PRFI (Relationship and Lifestyle-Quality of Life) | ||||||

| 3 | −1.96 | −4.21 | 0.29 | 0.50 | −1.77 | 2.76 |

| 6 | −1.91 | −4.45 | 0.63 | 0.97 | −1.58 | 3.52 |

| 9 | −2.88 | −5.43 | −0.33 | 1.26 | −1.27 | 3.79 |

| 12 | −1.72 | −4.26 | 0.82 | 0.77 | −1.76 | 3.29 |

| 15 | −1.47 | −4.17 | 1.23 | 1.73 | −0.90 | 4.35 |

| 18 | −0.64 | −3.38 | 2.10 | 0.15 | −2.57 | 2.88 |

| LSMeans Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| PRFI (B+C) Overall | −2.37 | −4.74 | 0.00 | 0.05 | ||

| Longitudinal Analysis of PCL-5 | ||||||

| 3 | −3.37 | −5.33 | −1.40 | −1.06 | −3.04 | 0.93 |

| 6 | −4.17 | −6.32 | −2.03 | −1.18 | −3.33 | .98 |

| 9 | −4.88 | −7.13 | −2.64 | −0.11 | −2.34 | 2.12 |

| 12 | −2.15 | −4.45 | 0.15 | −0.80 | −3.09 | 1.49 |

| 15 | −3.18 | −5.58 | −0.79 | −1.42 | −3.77 | 0.93 |

| 18 | −3.66 | −6.09 | −1.23 | −0.82 | −3.24 | 1.59 |

| LSMeans Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Overall 18 months | −1.9 | −3.91 | 0.12 | 0.07 | ||

| 3 | −3.3805 | −5.35 | −1.41 | −0.91 | 1.02 | 1.09 |

| 6 | −4.2028 | −6.36 | −2.05 | −0.91 | 1.11 | 1.27 |

| 9 | −5.1296 | −7.44 | −2.82 | 0.22 | 1.17 | 2.53 |

| 12 | −2.2904 | −4.69 | 0.11 | −0.24 | 1.22 | 2.17 |

| LSMeans Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Overall 12 months | −2.16 | −4.27 | −0.06 | 0.04 | ||

| 3 | −3.3077 | −5.28 | −1.33 | −0.90 | 1.02 | 1.10 |

| 6 | −4.0611 | −6.22 | −1.90 | −1.01 | 1.11 | 1.18 |

| 9 | −5.2057 | −7.53 | −2.88 | 0.10 | 1.18 | 2.42 |

| LSMeans Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Overall 9 months | −2.41 | −4.55 | −0.27 | 0.03 | ||

PTSD Baseline Assessments and Outcomes

The baseline severity for current PTSD symptoms was in the upper-end of moderate range, as shown by self-report PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015) mean score of 52.5 (SD = 11). At baseline, the two groups were similar in PCL-5 scores (IPS mean 46.2 [SD ± 15.8]; TW 45.1 [SD ± 17.0]) as well as distribution between categories of severity (see Table 2). Over 18 months, there was not a significant between-group difference in PTSD symptom change from baseline (−1.90; 95% CI, −3.91 to .12; p = .07), although a trend for improved PTSD symptom change in the IPS group compared to TW at month 18, and significant difference favoring IPS at month 9 and 12 (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that IPS supported employment improves functioning in unemployed veterans with PTSD across the domains of work/school, relationships, and lifestyle, with specific relevance to how core symptoms of PTSD impact these areas. Our findings suggest that the IPS approach promotes recovery and has important benefits beyond the job itself. After years of struggling with unemployment, veterans living with PTSD have the opportunity for increased quality of life and reconnection with family and friends, when they are given the support needed to obtain and maintain steady work. IPS is grounded on patient-centered community-based employment, integration with PTSD treatment, and follow-along support by an IPS employment specialist.

PTSD is associated with significant decline in social and occupational functioning that leads to a significant healthcare burden, societal costs, and increased utilization of medical services (Calhoun, Bosworth, Grambow, Dudley, & Beckham, 2002; Frueh, Grubaugh, Elhai, & Buckley, 2007). As noted by McCaslin and colleagues (2016), the research on the relationship between severity of PTSD symptoms and impairment in functioning is mixed, with some but not all studies demonstrating an association between these variables. For example, a recent study of treatment-seeking service members found that PTSD severity was significantly associated with lower mental health functioning on the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey, whereas PTSD severity was not associated with worse physical health functioning (Asnaani et al., 2018), contrary to other research (Possemato, Wade, Anderson, & Ouimette, 2010). In addition, functioning can continue to be impaired even after a reduction or resolution of PTSD symptoms, suggesting that ameliorating symptoms may not be sufficient to effectively improve functioning (Bryant et al., 2016). Change in severity of PTSD symptoms is not always concordant with change in functioning, which is the case of the VIP-STAR study. Although there was a trend for improved PTSD symptom change in the IPS group compared to TW, especially during the first 12 months, the two groups did not significantly differ in PTSD symptom change from baseline over the full 18 months. This finding suggests that the difference between IPS and TW on the PRFI, which reflects the perception of impact of PTSD symptoms on functioning, cannot be fully explained by changes in PTSD symptom severity.

A striking finding in our study was that the PTSD-related functioning scores did not significantly correlate with the number of weeks in competitive employment. This finding suggests that differences on functioning outcomes between the IPS and TW group cannot be fully explained by engagement in competitive work. The impact of competitive employment on specific measures of functioning varies across studies; for example, Kukla, Bond, and Xie (2012) did not find a relationship between competitive work and satisfaction with leisure and finances, whereas Bond et al. (2001) concluded that over time those who worked competitively had higher scores on these variables than the those who worked minimally or not at all.

The differential impact of the IPS versus TW on veterans’ perception of functioning due to PTSD may be explained by the patient-centered focus of IPS on identifying jobs consistent with the person’s preferences and abilities, the process of rapid job search, individualized job coaching, and the integration of clinical and vocational services (Bond, 2004), which are distinctions from transitional work. In this regard, IPS may be particularly well-matched for addressing the PTSD-related difficulties in occupational, interpersonal, and social lifestyle domains. An IPS specialist helps the veteran with PTSD re-enter community settings and make active contact with community employers, which could directly impact a veteran’s perception of the degree to which he/she is impacted by avoidance of people, activities, and places. Avoidance is a hallmark of PTSD and social isolation delays the natural processes of fear-extinction, since the individual is not exposed to new situations that prove to be safe despite initial hypervigilance and fear. This is one reason why many veterans recovering from PTSD might not be able to make gains towards employment in the early phase of treatment, furthering a sense of demoralization and helplessness. The IPS model calls for integrating employment support with mental health care from the outset, rather than waiting until symptoms have stabilized to offer employment, which is more typical of traditional vocational rehabilitation.

Perhaps a job can serve as a form of behavioral therapy, in that it can be the driving force to prevent an individual from getting reclusive and from believing that PTSD symptoms prevent participation in meaningful occupational and social activities. In this way, IPS practices are consistent with the principles of an evidence-based psychotherapy (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007), in that participation in a job search process may serve to expose veterans to positive circumstances that modify negative beliefs about the workplace and about their ability to achieve employment, reducing veterans’ perception of the impact of PTSD symptoms on their ability to function in different domains.

Veterans who are unemployed and living with PTSD may have low confidence in their ability to market themselves and interact with employers. The IPS specialist can model interactions with employers and provide in vivo coaching for veterans to increase not only skill but confidence in these interactions, despite residual symptoms of PTSD. Benight & Bandura (2004) identified perceived coping self-efficacy as vital to recovery from PTSD. Defined as “perceived capability to manage one’s personal functioning and the myriad environmental demands of the aftermath occasioned by a traumatic event” (p. 1130), this perception can be developed through in vivo coaching, modeling, and feedback about discrepancies between beliefs and actual outcomes (Benight & Bandura, 2004). To effectively reenter the workplace with dignity and success, the veteran living with PTSD must maneuver through a civilian workplace, which can be much less daunting with the help of a skilled IPS specialist. IPS establishes an interim support system to address one’s identity, self-efficacy, and self-worth through employment, and advances the resilience-building work of recovery from trauma. Finally, IPS is also deeply focused on building relationships within the community and workplace, which is a benefit to veterans who have distanced themselves from friends or family.

Strengths of the study include its large sample size, multisite geographic distribution, valid comparison group, minority representation, and 18-month outcome assessment period. Of note, this VA study had the goal of randomizing 540 participants over 17 months and the investigators met this recruitment goal on time. The study’s success in recruitment demonstrates the interest and willingness of veterans and providers to embrace the goal of employment for unemployed veterans with PTSD at these sites. Further examination of the implementation of this trial may serve to guide dissemination and generalization of the IPS supported employment intervention for veterans with PTSD to other sites.

A limitation of the study relates to assessment in that the PRFI is a self-reported measure, but to date there is no evidence that an independent assessment is better than self-report as it pertains to functioning. Another limitation is the inclusion criterion “interested in competitive work”, which does not allow the results to be generalized to veterans with PTSD who are not interested in returning to competitive work. While this is completely consistent with the principles inherent in recovery-oriented mental health care in terms of respect for a person’s preferences and individual autonomy (Bond et al., 2008), previous failures at work, fears about worsening symptoms, and concerns about losing disability income benefits can dampen a veteran’s interest in pursuing employment and engaging in vocational rehabilitation services (Drebing et al., 2012).

Future research needs to evaluate how the factors such as self-efficacy or reduced avoidance are associated with functional outcomes, IPS participation, and employment for individuals with PTSD. As more is understood about the active ingredients that yield these outcomes, IPS and other evidence-based interventions for PTSD can be enhanced and combined in ways to more fully restore the lives of the growing numbers of veterans with disabilities. When provided with support and encouragement from the IPS employment specialist and given a job that has relevance to individual preferences or abilities, veterans with PTSD can benefit therapeutically from the IPS service, as shown by these data. It is also possible that the active ingredients within IPS that are shared by other psychosocial interventions (supported education for example) could be investigated as to their impact on functional outcomes for veterans with PTSD; thus, increasing participation among veterans with an education goal rather than an immediate employment goal. The use of the PRFI to examine these potential outcomes may be a beneficial addition to measurement of the impact of psychosocial interventions for veterans with PTSD.

Implications for Practice

Based on these results, IPS should be routinely offered to veterans with PTSD to address employment needs and functioning deficits due to PTSD, ideally as early as possible when they enter VA care. Sripada et al. (2018) discovered that 86% of veterans with PTSD endorsed an interest in using VA employment services, whereas only 14% had actually participated in services. This high level of veteran interest in VA vocational rehabilitation could be leveraged as an additional engagement tool for veterans to utilize mental health services who may not perceive a need for treatment or who express concerns about utilizing mental health services. IPS is uniquely positioned to address this gap due to (a) the employment specialist’s observation of the veteran in the community and the provision of feedback as to what extent PTSD symptoms may be interfering with employment tasks and goals and (b) the collaboration between the employment specialist and the clinical team to facilitate warm handoffs increasing ease of access and to address concerns about treatment including potential narrowing of employment opportunities. These barriers were among those mentioned by veterans who screened positive for a potential mental health need (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2018). A future area of research could be focused on combining IPS with other evidence-based treatments for PTSD.

Conclusion

The VIP-STAR trial stands out as the largest ever study of IPS conducted in VA settings that focused on veterans with a PTSD diagnosis and included a measure of PTSD-related functioning. IPS participants reported significantly improved functional outcomes compared to TW participants. Mainstream competitive employment provides the veteran with structure, income, sense of purpose, means to reintegrate with friends and family, and other intangible lifestyle-enhancing benefits. Recovery is a multifaceted process in which people with disabilities move beyond preoccupation with symptoms and become hopeful to pursue their own journeys and goals (Whitley & Drake, 2010). Individuals who gain steady employment report increased self-esteem, decreased psychiatric symptoms, reduced social disability, and greater quality of life (Bond et al., 2001; Burns et al., 2009). For those who become steady workers, mental health treatment costs decline dramatically (Bush, Drake, Xie, McHugo, & Haslett, 2009). This analysis lends support to the notion that IPS can improve PTSD-related functional outcomes that go beyond work or school roles and include one’s capacity to experience more meaningful relationships with family and community and improve one’s lifestyle and quality of life.

Impact and Implications.

This paper adds evidence to the literature demonstrating that in addition to improving employment outcomes and occupational functioning for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services are shown to significantly improve functioning in the nonvocational areas of interpersonal relationships, daily lifestyle, and quality of life. For these reasons, expanded access to IPS supported employment in VA settings should be provided to more veterans recovering from PTSD.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by Cooperative Studies Program, Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development (CSP #589). Opinions herein are those of the individual authors and the contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

We acknowledge the support of the Research and Development Services at the participating medical centers, as well as the CSP#589 Coordinating Center at the West Haven VA Medical Center and the CSP#589 Study Chairs Office at the Tuscaloosa VA Medical Center.

Contributor Information

Lisa Mueller, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital, Bedford, MA; VISN 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center; Bedford, MA.

William R. Wolfe, San Francisco VA Medical Center, San Francisco, CA; University of California, San Francisco

Thomas C. Neylan, San Francisco VA Medical Center, San Francisco, CA; University of California, San Francisco

Shannon E. McCaslin, National Center for PTSD, Dissemination & Training Division, VA Palo Alto HCS, Menlo Park, CA VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park CA.

Rachel Yehuda, James J. Peters VAMC, Bronx, NY..

Janine D. Flory, James J. Peters VAMC, Bronx, NY.

Tassos C. Kyriakides, Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT

Rich Toscano, Tuscaloosa VA Medical Center, Tuscaloosa, AL.

Lori L. Davis, Tuscaloosa VA Medical Center, Tuscaloosa, AL; University of Alabama School of Medicine

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: Author; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asnaani A, Kaczkurkin AN, Benhamou K, Yarvis JS, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughan S, … Foa EB; STRONG STAR Consortium. (2018). The influence of posttraumatic stress disorder on health functioning in active-duty military service members. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 307–316. doi: 10.1002/jts.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill LA, Averill CL, Kelmendi B, Abdallah CG, & Southwick SM (2018) Stress Response Modulation Underlying the Psychobiology of Resilience. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(4):27. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0887-x. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, & Bandura A (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, Swanson SJ, Reese SL, Bond GR, & McLehman BM (2015). Supported Employment Fidelity Review Manual, Third Edition New Hampshire: Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, & Keane TM (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR (2004). Supported employment: Evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27, 345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, & Vogler KM (1997). A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 40, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, & Drake RE (2014). Making the case for IPS supported employment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR (2008). An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31, 280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, & Bebout RR (2001). Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(3), 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, McFarlane AC, Silove D, O’Donnell ML, Forbes D, & Creamer M (2016). The lingering impact of resolved PTSD on subsequent functioning. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(3), 493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, White S, Becker T, Koletsi M, Fioritti A, ... & Lauber C (2009). The impact of supported employment and working on clinical and social functioning: results of an international study of individual placement and support. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(5), 949–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush PW, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, & Haslett WR (2009). The long-term impact of employment on mental health service use and costs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 60(8), 1024–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, & Beckham JC (2002). Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 2081–2086. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric V, Stock EG, Pultz J, Marcus R, & Sheehan DV (2009). Sheehan suicidality Tracking Scale (Sheehan-STS): Preliminary results from a multicenter clinical trial in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmon), 6, 26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Kyriakides TC, Suris A, Ottomanelli L, Drake RE, Parker PE, ... & McCall KP (2018a). Veterans individual placement and support towards advancing recovery: Methods and baseline clinical characteristics of a multisite study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(1), 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Kyriakides TC, Suris AM, Ottomanelli LA, Mueller L, Parker PE, ... & Drake RE (2018b). Effect of evidence-based supported employment vs transitional work on achieving steady work among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Leon AC, Toscano R, Drebing CE, Ward LC, Parker PE, … & Drake RE (2012). A randomized controlled trial of supported employment among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services, 63(5), 464–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, Anthony WA, & Clark RE (1996). The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drebing CE, Mueller L, Van Ormer EA, Duffy P, LePage J, Rosenheck R, ... & Penk W (2012). Pathways to vocational services: Factors affecting entry by veterans enrolled in Veterans Health Administration mental health services. Psychological Services, 9(1), 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SC, Schnurr PP, Kulish AL, Holowka DW, Marx BP, Keane TM, & Rosen R (2015). Psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in male and female Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans: The VALOR registry. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(12), 1038–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, & Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences, therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, & Buckley TC (2007). US Department of Veterans Affairs disability policies for posttraumatic stress disorder: Administrative trends and implication for treatment, rehabilitation, and research. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 2143–2145. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla M, Bond GR, & Xie H (2012). A prospective investigation of work and nonvocational outcomes in adults with severe mental illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(3), 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley PA, & Joseph S, 2004. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(1), 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaslin SE, Maguen S, Metzler T, Bosch J, Neylan TC, & Marmar CR (2016). Assessing posttraumatic stress related impairment and well-being: The Posttraumatic Stress Related Functioning Inventory (PRFI). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 72, 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WC, Xie H, Bond GR, Drake RE, & Dain BJ (1997). Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: A longitudinal analysis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(7), 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Drake RE, & Bond GR (2016). Recent advances in research on supported employment for people with serious mental illness. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018). Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/24915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottomanelli L, Barnett SD, & Goetz LL (2014). Effectiveness of supported employment for veterans with spinal cord injury: 2-year results. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(4), 784 – 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penk W, Drebing CE, Rosenheck RA, Krebs C, van Ormer A, & Mueller L (2010). Veterans Health Administration transitional work experience vs. job placement in veterans with co-morbid substance use and non-psychotic psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(4), 297 – 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Wade M, Andersen J, & Ouimette P (2010). The impact of PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders on disease burden and health care utilization among OEF/OIF veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2, 218–223. 10.1037/a0019236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E & Clark LA (2009) Psychosocial functioning in the context of diagnosis: Assessment theoretical issues. Psychological Assessment, 21, 313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada RK, Henry J, Yosef M, Levine DS, Bohnert KM, Miller E, & Zivin K (2018). Occupational functioning and employment services use among VA primary care patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(2), 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt D, Smith BN, Fox AB, Amoroso T, Taverna E, & Schnurr PP (2017). Consequences of PTSD for the work and family quality of life of female and male US Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R, & Drake RE (2010). Recovery: A dimensional approach. Psychiatric Services, 61(12), 1248–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]