Abstract

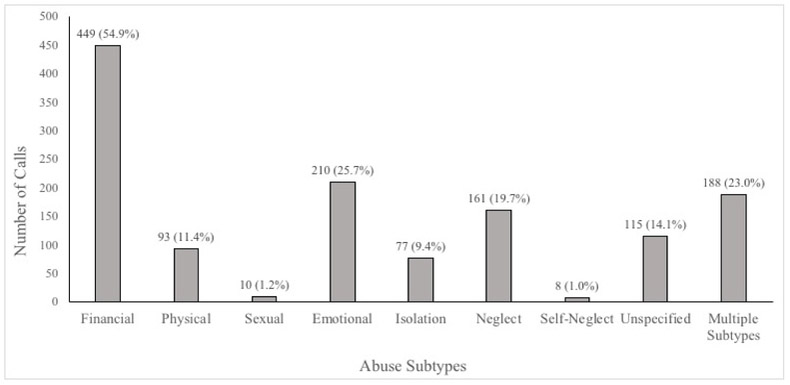

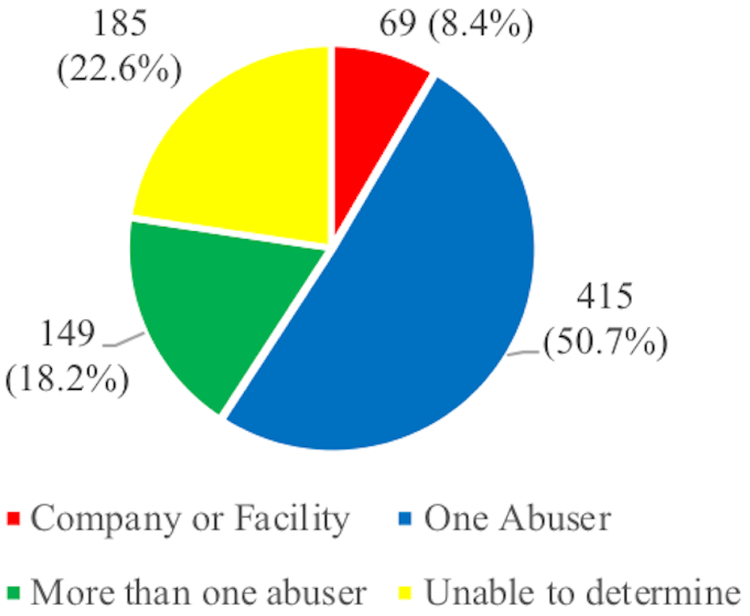

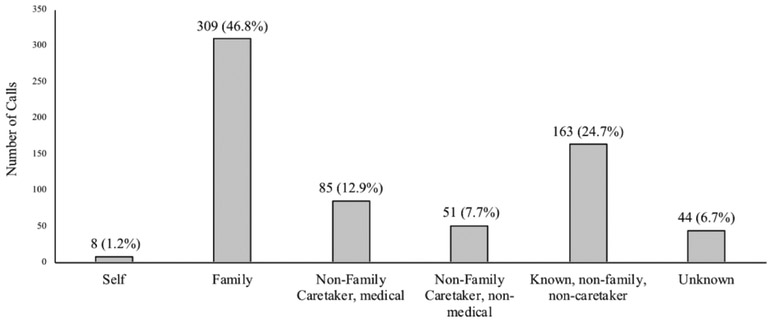

Characterizing types of elder abuse and identifying characteristics of perpetrators is critically important. This study examined types of elder abuse reported to the NCEA resource line. Calls were coded in regards to whether abuse was reported, types of abuse alleged, whether multiple abuse subtypes occurred, and who perpetrated the alleged abuse. Of the 1939 calls, 818 (42.2%) alleged abuse, with financial abuse being the most commonly reported (449 calls; 54.9%). A subset of calls identified multiple abuse types (188; 23.0%) and multiple abusers (149; 18.2%). Physical abuse was most likely to co-occur with another abuse type (61/93 calls; 65.6%). Family members were most commonly identified perpetrators (309 calls, 46.8%). This study reports characteristics of elder abuse from a unique source of frontline data, the NCEA resource line. Findings point to the importance of supportive resources for elder abuse victims and loved ones.

Keywords: abuse and neglect, mistreatment, caregiving, observational studies

Introduction

The population of adults aged 65 and older in the United States is growing rapidly (US Census Bureau, 2017). Of critical importance to ensuring the well-being of older adults is addressing the public health issue of elder abuse. Elder abuse results in physical, psychological, and social consequences to victims, their families, and society (Mosqueda & Dong, 2011; Pillemer, Connolly, Breckman, Spreng, & Lachs, 2015). Additionally, costs associated with elder abuse are estimated to contribute more than $5.3 billion of the nation’s annual health expenditures (Dong, 2005). Characterizing the types of elder abuse and identifying characteristics of perpetrators are necessary steps towards addressing this public health crisis.

The vast consequences of elder abuse underscore the need for services targeted towards assisting older adults who are at risk for or who have experienced elder abuse. The primary agency for coordinating investigation and services for victims of abuse is adult protective services (APS). Since APS procedures can vary significantly by state due to differences in state laws, interpretation of laws, and funding (Mosqueda & Dong, 2011), uniform metrics about elder abuse cases in the United States are not collected by APS agencies, even in the face of the recent establishment of the National Adult Maltreatment Reporting System (Acker et al., 2018). Consequently, information on what constitutes elder abuse and whether elder abuse has been identified in current datasets may differ based on the source. The National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) resource line, established in 2011, serves as a public access point for individuals seeking resources or advice regarding how to identify or report elder abuse. Since 2014, individuals can reach out via various methods, including telephone, email, or social media (Facebook, Twitter). As such, data from the NCEA resource line can serve as a unique frontline opportunity to investigate elder abuse characteristics across the United States.

Due to lack of uniform nationwide data standards, understanding the scope of the problem of elder abuse using administrative data has proven challenging. In recent years, there has been an increase in studies investigating the prevalence and associated factors of elder abuse. Prevalence rates of elder abuse vary across studies largely due to the variable methods in which rates are estimated and abuse is defined (Hall, Karch, & Crosby, 2016). In three more recent large-scale surveys conducted in the United States, one-year prevalence rates ranged from 7.6% to over 11% (Acierno et al., 2010; M. Lachs & Berman, 2011; Laumann, Leitsch, & Waite, 2008), suggesting that approximately 1 in 10 older adults will experience elder abuse within a one-year period (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; Pillemer et al., 2015). Although these findings highlight the ubiquitous problem of elder abuse, they are likely underestimates, as many cases of elder abuse go unreported due to factors including embarrassment, fear, denial, isolation, lack of resources, or lack of knowledge about reporting procedures (Lachs & Berman, 2011; Mosqueda & Dong, 2011; National Center on Elder Abuse, 1998).

Previous studies examining elder abuse have generally been surveys (e.g., Acierno et al., 2010; Amstadter et al., 2011; Lachs & Berman, 2011; Laumann et al., 2008) or studies that have retrospectively examined APS data or other reports (Choi, Kulick, & Mayer, 1999; Choi & Mayer, 2000; Lachs, Williams, O’brien, Hurst, & Horwitz, 1996; Moon, Lawson, Carpiac, & Spaziano, 2006; National Center on Elder Abuse, 1998). The latter is more likely to reflect cases in which the reporter is certain or greatly suspects that abuse has occurred and wishes to prompt an investigation, while the former is based on self-report and as such, is vulnerable to survey sampling bias. Individuals self-select whether to contact the NCEA resource line, and because it is an informational resource, many calls are made to inquire about ambiguous cases of abuse, thus capturing a wide range of possible abuse situations. Thus, the NCEA resource line provides an additional and unique source of information to the literature on characteristics of elder abuse cases in the United States. The goal of this study was to examine the frequency of different types of elder abuse described in contacts made to the NCEA over a three-year period in order to (1) identify the most common types of elder abuse alleged and (2) examine the most common victim-perpetrator relationships in the context of a resource line.

We expected that the majority of calls or messages placed to the NCEA would entail elder abuse disclosure. Since many studies on elder abuse reported financial abuse as the most prevalent subtype of abuse (Amstadter et al., 2011; Lachs & Berman, 2011), including those studying complex cases that require heightened levels of consultation (e.g., Navarro et al., 2010), we hypothesized that most NCEA calls would concern financial abuse. Many population studies (e.g., Burnes et al., 2015; Laumann et al., 2008), however, indicate psychological abuse as the most prevalent form of elder abuse, as reflected in a recent cross-national systematic review (Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis, & Wilber, 2017), and thus we hypothesized that this type of abuse would be more commonly reported than physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and self-neglect subtypes.

In addition to investigating frequency of abuse subtypes, we also sought to investigate the rate of calls alleging multiple abuse subtypes and which types most commonly co-occurred. We expected that a sizeable subset of calls would allege multiple types of abuse (e.g., Fisher & Regan, 2006; Jackson & Hafemeister, 2013; Paris, Meier, Goldstein, Weiss, & Fein, 1995; Post et al., 2010; Vilar-Compte & Gaitán-Rossi, 2018). We additionally expected that physical abuse would most commonly co-occur with other abuse types given two previous reports, one in a long-term care setting (Post et al., 2010) and one of older women (Fisher & Regan, 2006). Finally, we predicted that abuse would be most commonly committed by a family member (see Lachs & Pillemer, 2015 for review).

Methods

National Center on Elder Abuse

The National Center on Elder Abuse (https://ncea.acl.gov/) provides advice and resources to individuals via their resource line, website, and social media pages. Individuals can call the resource line and speak to an NCEA staff member, post messages via social media platforms, or send emails via the NCEA website. Staff members are knowledgeable about elder abuse and available resources including investigative organizations such as APS. Calls, emails, or messages to the resource line are summarized into a narrative and logged into a database by NCEA staff. Responses by NCEA staff are also logged. For simplicity, all formats of contact made to the NCEA resource line (calls, emails, social media messages) will be subsequently referred to as “calls”.

Although the NCEA is not a resource for reporting elder abuse, callers may contact the NCEA to receive information regarding how to report elder abuse. When an elder abuse situation is disclosed, callers are provided with the information necessary to report the alleged elder abuse (e.g., local APS number). If the situation is deemed emergent, NCEA staff will call APS directly to make a report.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ home institution. Calls received between August 2014 and June 2017 were reviewed for any mention of elder abuse. Prior to receiving the final list of calls, a staff member de-identified call narratives and removed personally identifying information from the database. This removed the option of describing characteristics of callers in the present study. Duplicates were removed based on calls that provided identical information from an identical source. Repeated calls from the same caller were considered duplicates if they disclosed the same case of elder abuse and no new information was given.

All de-identified calls were reviewed by two independent raters, who first identified whether or not alleged elder abuse was reported in each call (note that although the NCEA is not a reporting service, we refer to calls disclosing elder abuse as “reports” for simplicity). Elder abuse was determined by reviewing the caller’s narrative (summary of phone call by NCEA staff member, or direct quote in the case of emails, social media posts, or letters) and NCEA’s response narrative (summary of staff member’s response and any action taken), as responses often provided additional information. For example, if the call narrative was vague but the response narrative indicated that a number for APS was provided, this call was coded as a “report” of abuse. Duplicates were further identified during this process. Following identification of elder abuse, abuse calls were categorized into one or more of six elder abuse subtypes based on call narratives and responses: financial, physical, sexual, emotional, neglect, and self-neglect. Disagreements in ratings for overall abuse and abuse subtypes were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third rater and the research team. Following this procedure, calls were further coded for number of abusers reported per call and the relationship of the abuser to the victim. Number of abusers per call were coded as one abuser, more than one abuser, staff of a company or facility (e.g., long-term care, nursing facility, assisted living) committing the alleged abuse, or unable to determine based on the information provided in the narrative. Relationship to the victim was coded as self (for instances of self-neglect), family, non-family non-medical caregiver, non-family medical caregiver, an individual (or entity) known to the victim who does not fit the other categories, a stranger (e.g., telephone solicitor), or unable to determine based on the information provided in the narrative. The decision to code staff of a company or facility under the “number of abusers” category rather than the “relationship” category was made in order to capture the different types of relationships that could fall within this classification (e.g., nursing home would reflect a “non-family, medical caregiver” relationship; a business that took financial advantage of an older adult would reflect an “individual (or entity) known to the victim who does not fit other categories” relationship).

Specific procedures for rating calls were as follows: A preliminary codebook was developed by the research team through review of the scientific literature on elder abuse and expert knowledge on the topic. All calls were independently coded by two raters using the initial codebook. After a set number of calls were coded, the two raters met to review the coding and identify discrepanices. All dispcrepancies were resolved via discussion with a third rater and the research team when indicated, until consensus was reached. Necessary modifications were iteratively made to the coding scheme when information that did not fit the initial coding scheme emerged from the data and discussions. In total, the two raters agreed on 94.8% of the initial codes (n=101 disagreements out of 1954 total calls received) for overall abuse prior to consensus discussion. Percent disagreement by subtype of abuse was calculated based on the number of times raters disagreed about the subtype of abuse being reported out of the 818 calls reporting abuse (note that some calls reported multiple subtypes of abuse). Disagreement was highest for emotional abuse (16.6%, 136 calls), followed by financial abuse (8.1%, 66 calls), neglect (7.0%, 57 calls), physical abuse (6.7%, 55 calls), sexual abuse (0.5%, 4 calls), and self-neglect (0.4%, 3 calls).

Definition of Elder Abuse and Subtypes: Elder abuse was defined as, “An intentional act or failure to act by a caregiver or another person in a relationship involving an expectation of trust that causes or creates a risk of harm to an older adult.” An older adult is defined as an individual 60 years of age or older. Definitions of elder abuse generally, and physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, financial abuse/exploitation, and self-neglect can be referenced in the CDC’s report (Hall et al., 2016) and in Table 1. Based on these definitions, calls reporting emotional abuse were further categorized as to whether they reported isolation/coercion. Although the CDC definition of elder abuse specifies abuse as that committed by a trusted individual, we included “strangers” when classifying abuser-victim relationships (e.g., to capture financial exploitation by scammers) to reflect the range of calls received by the NCEA. This modification of the CDC’s definition of elder abuse is consistent with the United States Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Elder Justice Roadmap definition (DOJ, 2014). Self neglect was also included as a subtype of abuse although it is not identified as a standalone subtype in the CDC guidelines, but rather as a “related phenomenon.”

Table 1.

(a) Definitions used to code calls made to the NCEA helpline. Definitions are based on CDC guidelines with some modifications. (b) Descriptions of the types of relationships coded for.

| A. Definitions of abuse | ||

|---|---|---|

| Abuse type | Definition1 | Examples |

| Elder Abuse2 | An intentional act or failure to act by a person in a relationship involving an expectation of trust (including self, acquaintances, or strangers) that causes or creates risk of harm to an older adult. | |

| Physical Abuse | Intentional use of force resulting in physical pain, harm, injury, functional impairment, or distress. | Hitting, slapping, physical punishment, inappropriate use of medication or physical restraints. |

| Sexual Abuse | Forced or unwanted sexual contact or interaction. | Unwanted touching, fondling, suggestive talk, photography, voyeurism, or rape. |

| Emotional Abuse3 | Verbal or non-verbal interactions that result in fear, distress, psychological pain or anguish, or social or geographic isolation. | Threats (including physical), humiliation, disrespect. |

| Neglect | Failure by a caretaker to meet the basic needs (medical, nutrition, shelter, daily activities, protection) necessary for an older person’s physical and mental well-being. | Failure to provide adequate food, shelter, clothing, medical attention, or social stimulation. |

| Self-Neglect4 | Behavior by an elderly person that threatens his/her own health or safety. | Failure to provide one’s self with adequate food, shelter, hygiene. |

| Financial Exploitation5 Financial Abuse Financial Victimization | Improper, unauthorized, or fraudulent use of an older person’s property by a caregiver or trusted individual (abuse) or stranger (victimization) for the benefit of someone other than the elderly person. | Theft, inappropriate transfer or misappropriation of property; scams (sweepstake, grandparent, sweetheart) |

| B. Reported Abuser-Victim Relationship: | ||

| Relationship | Description | |

| Self | Self-neglect | |

| Family | Family member, including those designated as medical caretakers or with legal or fiduciary duties | |

| Non-family, medical caretaker | A person entrusted with the medical care or well-being of an older adult (e.g., doctors, nurses, nursing or home-health aides) | |

| Non-family, non-medical caretaker | A person entrusted with non-medical care or well-being of an older adult (e.g., legal guardian, POA, conservator) | |

| Known individual, not fitting above categories | An individual known to the victim but not fitting the above categories (e.g., friend, neighbor, lawyer (without guardian/conservator duties), financial manager, plumber etc). | |

| Stranger | An individual unknown to the victim (e.g., telephone or email scammer). | |

| Not reported | Relationship not mentioned in the “request narrative” or “response” descriptions | |

Definitions were adapted from CDC’s Uniform Definitions.

The CDC definition of elder abuse was expanded to include abuse by strangers, in order to capture financial exploitation by scammers, and abuse by “self’, to include self-neglect. This is consistent with The Elder Justice Roadmap definition by the Departmet of Justice (2014).

Emotional abuse reports were subcategorized based on presence of isolation/coercive control, as per CDC definitions.

CDC designates self-neglect as a “related phenomenon” instead of as a distinct abuse subtype. Self-neglect is considered a standalone subtype in this study.

Both financial abuse and victimization were considered financial exploitation in this study.

Per CDC guidelines, calls reporting abuse between residents of long-term care facilities were not considered abuse; however, abuse by a neighbor or roommate was coded as abuse if the elder was living in independent housing. Calls that reported a suboptimal living situation (e.g., lack of A/C or heating) due to low income were not considered abuse for the purpose of this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Calls were excluded if the victim resided outside of the United States or its territories. This was determined by the raters when reading the call narratives (e.g., a caller reported on a friend living in South America). Calls that reported abuse of an individual who is now deceased were only considered abuse if the death was presumed to be caused by the alleged abuse. Vague calls (e.g., a caller requesting information about elder abuse) were not considered to be abuse unless the NCEA response narrative provided APS or police numbers to the caller, or referenced a specific case of abuse.

Descriptive Analyses of Calls

Total calls identifying abuse were tallied and percent of each abuse subtype was calculated by dividing the number of calls alleging a specific abuse subtype by the total number of abuse calls. The same procedure was done to determine specific relationships to the victim and number of abusers across all calls. To determine these values for each specific subtype, the denominator became total calls alleging each specific subtype of abuse. Calls that identified multiple different types of abuse and/or relationships were included within each relevant descriptive analysis, such that some calls were represented more than once. When relevant, this information is described in the text of the results.

Results

There were 1954 de-identified calls received from the NCEA. Fifteen additional duplicates were identified by reviewing call narratives, leaving 1939 unique calls for coding. Of these, 818 calls (42.2%) reported abuse of an older adult, 30 calls (1.5%) were excluded because the victim was reported to reside outside of the United States or was younger than 60 years of age, and 1091 (56.2%) calls did not allege any abuse.

Subtypes of Alleged Abuse

Figure 1 presents rates of abuse by subtype. Of the 818 calls identifying abuse, 1046 total (not including isolation) subtypes of abuse were reported (many calls reported more than one subtype of abuse). Calls to the resource center most commonly concerned financial abuse, followed by emotional abuse, neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and self neglect. There were 115 calls that did not provide enough information to determine abuse subtype (e.g., narrative only stated, “I am calling to report abuse of an older adult”).

Figure 1.

Frequency of abuse subtypes reported to the NCEA call center. Calls alleging isolation were part of the emotional subtype, per CDC guidelines (Hall et al., 2016). Bars are labeled with the number (%) of 818 total calls.

There were 188 calls (23.0% of 818) that indicated more than one abuse subtype. The most common subtype to be reported along with at least one other subtype was physical abuse, followed by emotional abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, self-neglect, and financial abuse. Both financial abuse and physical abuse most commonly co-occurred with emotional abuse. Neglect most commonly co-occurred with financial abuse, followed closely by emotional abuse. The breakdown of co-occurrence between abuse subtypes is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of calls that report more than one subtype of abuse (panel A). Number of calls that report co-occurring subtypes are presented in Panel B. Percentages in panel A use the total number of calls reporting each subtype as that row’s denominator. Note that row sums of panel B differ from the corresponding total number of calls listed in panel A because some calls reported more than two different subtypes of abuse.

| A. Calls Reporting >1 Subtype (N=188) |

B. Co-Occurrence Between Subtypes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Total calls |

Percent | Financial | Physical | Sexual | Emotional | Neglect | Self-Neglect | |

| Financial | 137 | 449 | 30.5% | - | 36 | 2 | 91 | 45 | 0 |

| Physical | 61 | 93 | 65.6% | - | - | 1 | 37 | 16 | 1 |

| Sexual | 5 | 10 | 50.0% | - | - | - | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Emotional | 131 | 210 | 62.4% | - | - | - | - | 39 | 0 |

| Neglect | 79 | 161 | 49.1% | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| Self-Neglect | 3 | 8 | 37.5% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Of the 630 calls that alleged only one abuse subtype, 312 (49.5%) reported financial abuse, 82 (13.0%) reported neglect, 79 (12.5%) reported emotional abuse, 32 (5.1%) reported physical abuse, and five each reported sexual abuse (0.8%) and self-neglect (0.8%).

Characteristics of Alleged Abuser

Calls were assessed for the number of abusers alleged in each narrative (Figure 2). Of the 818 calls alleging abuse, 415 (50.7%) indicated only one abuser. More than one abuser was reported in 149 calls (18.2%), and 69 calls (8.4%) alleged abuse by a company or facility. There were 185 calls (22.6%) in which the number of abusers could not be determined.

Figure 2.

Pie chart displaying breakdown of number (%) of abusers alleged across the 818 call narratives reporting elder abuse.

Calls were also coded for the relationship of the abuser to the victim (Figure 3), using six mutually exclusive categories: self, family, non-family non-medical caregiver, non-family medical caregiver, an individual (or entity) known to the victim who does not fit the other categories, a stranger (e.g., telephone solicitor), or unable to determine based on the information provided. Of the 818 calls, 175 (21.4%) did not specify relationship. Of the 643 calls in which relationship could be determined, there were 660 relationships recorded. Calls with multiple abusers with the same type of relationship (e.g., two family members) were coded as one relationship; 17 calls reported multiple abusers who fell into different categories (e.g., family and caregiver). Of these 660 relationships, abuse was most commonly alleged to have been committed by a family member, followed by an individual known to the victim (non-family, non-caregiver), medical caregivers, non-medical caregivers, and an abuser not previously known to the victim.

Figure 3.

Breakdown of reported abuser’s relationship to the victim across the 660 total instances in which a relationship was reported. There were 175 calls in which a relationship could not be determined. Bars are labeled with the number (%) of the 660 total relationships reported.

Given that abuse was most commonly alleged to have been committed by a family member, we examined which abuse subtypes were most commonly committed by family members. Of the 309 calls disclosing abuse allegedly committed by a family member, the most common abuse subtype to be reported was financial abuse (191 calls, 61.8%), followed by emotional abuse (108 calls, 35%), neglect (62 calls, 20.1%), physical abuse (37 calls, 12.0%), and sexual abuse (1 call, 0.3%). Of the 309 calls that alleged abuse by a family member, 101 calls (32.7%) reported more than one abuse subtype.

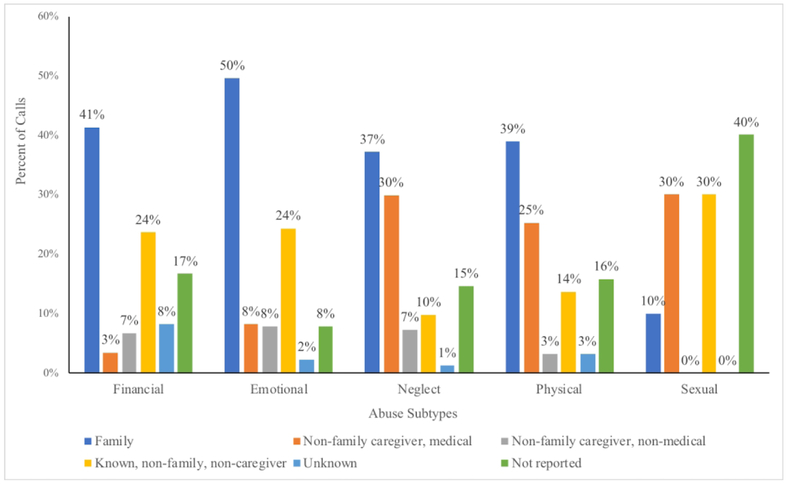

We also examined abuser-victim relationships across each abuse subtype, with the exception of self-neglect. For financial abuse, there were 462 relationships identified across 449 calls (13 calls reported more than one abuser falling into different categories). Of the 462 relationships identified, abuse by a family member was most common, followed by an individual known to the victim (non-family, non-caregiver), individuals unknown to the victim, non-medical caregivers, and medical caregivers. There were 77 calls in which the relationship was not specified. For emotional abuse, there were 218 relationships reported across 210 calls. Of these, abuse by a family member was most commonly reported, followed by an individual known to the victim, a medical caregiver, a non-medical caregiver, and an unknown individual. There were 17 calls in which the relationship was not specified. For neglect, there were 164 relationships reported across 161 calls. Once again, abuse by a family member was most commonly disclosed, followed by a medical caregiver, an individual known to the victim, a nonmedical caregiver, and an unknown individual (e.g., “someone” withholding information about doctors who can help). There were 24 calls lacking information to determine relationship. For physical abuse, there were 95 relationships identified across the 93 calls. Family members were the most commonly alleged perpetrators of physical abuse, followed by medical caregivers, individuals known to the victim, non-medical caregivers, and unknown individuals. There were 15 calls that did not specify the relationship. With regard to sexual abuse, most calls did not report on relationship. The most commonly reported perpetrators were medical caregivers and individuals known to the victim. One call alleged sexual abuse by a family member; this call also alleged sexual abuse by a known individual. These patterns are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Frequency of abuser-victim relationships reported separately for the different abuse subtypes.

Discussion

In this descriptive study of NCEA call logs, we sought to characterize elder abuse reports by investigating the most commonly reported elder abuse subtypes and abuser-victim relationships in the context of a resource line. Of the 818 calls alleging abuse, financial abuse was the most commonly reported type of elder abuse. A large subset of calls (23%) identified more than one subtype of abuse, with physical abuse being the most common subtype to be reported along with at least one other type of abuse. Family members were the most commonly alleged perpetrators of abuse, and a subset of calls reported more than one abuser (18%).

This is the first study to characterize elder abuse from calls made to a resource line that serves as a public access point for individuals seeking information and resources about elder abuse. Findings highlight the importance of resource lines for those seeking information on elder abuse, as many calls were made to understand whether certain situations reflected abuse. While elder absue is a growing concern to public health, public awareness and information is still lacking. Providing resources (e.g., intervention resources, APS contact information) to individuals who are in need of information and support may help to stop an abusive act from occurring or from continuing to occur. Additionally, as this study captures a sample of individuals who self-selected to call the NCEA, it provides a unique source of front-line information regarding elder abuse. Characterizing types of elder abuse and characteristics of perpetrators across various data sources, including resource lines as was done in the present study, APS data, and large-scale surveys, is important in order to capture the range of individuals who experience elder abuse. Each of these sources likely represents a slightly different group of individuals and a different aspect of the threat elder abuse poses to public health. For example, large-scale epidemiological survey studies are likely to capture a wider and more representative group of individuals who have experienced elder abuse, but are based on self-report and thus vulnerable to underreporting. In contrast, utilizing a resource line as was done in this study allows for informant reports in addition to self-report, but is less representative of the larger population given that individuals self-select whether to contact the NCEA resource line. Thus, incorporating diverse data sources captures a wider net of individuals affected by elder abuse and a broader scope of the phenomenon.

Findings from this study are consistent with several previous large-scale survey studies and APS studies that also found financial abuse to be the most commonly reported type of abuse (Acierno et al., 2010; Amstadter et al., 2011; Lachs & Berman, 2011, Self-Reported Prevalence Study arm; Moon et al., 2006). Unlike Acierno et al. (2010) and Amstadter et al., (2011), we chose not to restrict our definition of financial abuse to that committed by a family member, and specifically included strangers as a relationship category, a decision consistent with the definition proposed by the Department of Justice’s Elder Justice Roadmap (DOJ, 2014). We made this decision because of high rates of financial exploitation perpetrated by telephone, mail, and internet scammers that are specifically targeted towards older adults (e.g., grandparent scam). Despite this, we found family members to be the most commonly alleged perpetrators of financial abuse. In fact, across all abuse subtypes as well as each subtype individually (with the exception of sexual abuse and self-neglect), abuse by a family member was the most commonly reported relationship. This finding is consistent with other studies (Biggs, Manthorpe, Tinker, Doyle, & Erens, 2009; Choi & Mayer, 2000; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015 for review; Moon et al., 2006; Peterson et al., 2014), and suggests that older adults living with multiple family members may be at greatest risk of certain types of elder abuse. We also found individuals who are known to the victim (non-family, non-caregivers) to be common perpetrators of emotional, financial, and sexual abuse (23.6%, 24.3%, and 30% respectively) and non-family medical caregivers to be common perpetrators of neglect, physical, and sexual abuse (29.9%, 25.3%, and 30.0%, respectively). These patterns suggest that certain types of abuse may be more commonly committed by certain types of perpetrators, and may shed light on vulnerabilities of older adults under various levels of care. For example, older adults living in nursing facilities may be more vulnerable to neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse given that they are more likely to be cared for by non-family medical caregivers. In contrast, independent older adults may be more likely to be victimized by individuals who they know from non-family, non-caregiver relationships (e.g., friends, business partners).

In addition to finding that family members were the most commonly alleged perpetrators, these data suggest that family members were more likely to commit multiple different types of abuse compared to other alleged perpetrators, with 32.7% of calls that identified a family member as the perpetrator alleged them committing multiple forms of abuse, compared to 23.0% of calls overall. Although the present study cannot evaluate mechanisms behind these findings, one possibility is that stress and burden associated with caregiving for a relative increase the likelihood of committing abuse (e.g., Schiamberg & Gans, 1999). Conversely, a study by Pillemer & Finkelhor (1989) found that abuse was a reflection of the relative’s problems and dependency on the victim rather than the elderly victim’s characteristics or caregiver burden. Lack of social support and isolation may further place an isolated elder at risk of abuse by family members and others (e.g., Acierno et al., 2010).

Findings diverge from studies and a recent meta-analysis of studies cross-nationally (Yon et al., 2017) that find emotional abuse to be the most prevalent subtype of abuse (e.g., Fisher & Regan, 2006; Lachs & Berman, 2011 Documented Case Study arm; Laumann et al., 2008; Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis, & Wilber, 2017); this study found emotional abuse to be the second most prevalent subtype in the context of a resource line. This may reflect differences in how abuse is defined. For example, Laumann et al. (2008) restricted their definition of abuse to that committed by a family member. Additionally, this may also reflect differences in samples used to examine elder abuse (e.g., Fisher & Regan, 2006, examined older women; Yon et al., 2017, meta-analysis included cross-national studies). This study was not a prevalence study in that we did not randomly sample the U.S. population. Instead, reports of abuse were made by individuals who chose to call the NCEA, introducing self-selection bias, which may skew reports of abuse in a particular direction. For example, whereas physical abuse may warrant an immediate call to APS, other types of abuse may be more nebulous to the caller, thus motivating an inquiry with the NCEA prior to making an elder abuse report to local APS. The nature of the NCEA as a resource line may also explain the very small number of calls disclosing self-neglect (8 calls). Self-neglect is the most common form of mistreatment encountered by healthcare professionals (Mosqueda & Dong, 2011), and healthcare professionals are less likely to require resources offered by the NCEA helpline or other elder abuse services. Self-neglect is also associated with lower levels of social relations (Dong, Simon, Beck, & Evans, 2010; see Mosqueda & Dong, 2011 for review), making it less likely for self-neglect to be noticed and reported by family and friends.

Almost a quarter of the calls alleging abuse indicated more than one subtype of abuse, and 18% of calls alleged multiple abusers. This latter finding is consistent with a prevalence study of elder abuse in New York state, which reported that 17% of respondents described two abusers (Lachs & Berman, 2011). Although we found that 50% of calls alleged only one abuser compared to 74% in Lachs and Berman’s (2011) study, this may be due to the fact that we were unable to determine the number of abusers in 22.6% of calls. Taken together, findings suggest that while abuse by multiple perpetrators occurs, abuse by a single perpetrator may be more common.

Our findings suggest that, in many cases, abusive actions are not isolated events; 23% of callers alleged more than one subtype of abuse, a finding in line with other studies noting high rates of poly-victimization (e.g., Vilar-Compte & Gaitán-Rossi, 2018; Fisher & Regan, 2006; Jackson & Hafemeister, 2013; Paris, Meier, Goldstein, Weiss, & Fein, 1995; Post et al., 2010). Also consistent with previous reports (Fisher & Regan, 2006; Post et al., 2010), we found that physical abuse was most likely to be alleged along with other subtypes of abuse. In contrast, financial abuse was least likely of the subtypes to co-occur with other types of abuse, consistent with one previous report (Moon et al., 2006), although overlap was still high for this subtype with approximately one-third of financial abuse calls alleging an additional form of abuse. Understanding which abuse subtypes commonly co-occur is important for identifying risk factors of abuse and establishing preventive measures. For example, one study found that certain unique risk factors were associated with severity of abuse, as measured by experiencing multiple types of abuse (Vilar-Compte & Gaitán-Rossi, 2018). The authors argue that considering abuse as a dichotomous variable rather than considering abuse on a spectrum of frequency and severity limits our ability to understand the complex phenomena of elder abuse. These findings point to the necessary consideration of multiple forms of abuse experienced by older victims. Specifically, future research and program development must consider the concepts of severity, poly-victimization, and the unique risk factors present in poly-victimization to address the full scope of elder abuse’s public health threat.

Contrary to our prediction, the majority of calls made to the NCEA did not allege abuse. This highlights the multifunctional role of the NCEA in educating and providing resources to the population on elder abuse. These findings also substantiate that the NCEA is classified as a resource center as opposed to an investigatory agency.

There are several limitations that deserve mention. First, the findings reported in this study are based on calls or messages made by individuals who took initiative to contact the NCEA resource line. This presents self-selection bias which may skew findings in a particular direction and precludes any prevalence determinations. For example, individuals working in geriatric care centers (e.g., geriatric physicians, nurses, medical caregivers, social workers) may be less likely to contact the NCEA resource line given their familiarity with the procedures for reporting elder abuse. Family members and friends of victims may be more likely to call the resource line given less access to information regarding elder abuse and reporting procedures. We cannot predict how this might impact the data, but this is an interesting avenue of future research. We are also unable to determine how similar the population of callers is to other populations of adults and older adults who report or experience elder abuse, and we were unable to conduct an extensive evaluation of the identity of the callers and differences between those reporting abuse and those not reporting abuse due to de-identification of calls prior to study authors receiving the dataset. For example, there may be differences between these groups in regard to socioeconomic status, social support, health status, and demographic factors that may be interesting and informative. Future research may focus on such questions. As the NCEA is a resource line and was not established for research purposes, there are no scripts or consistent questions asked of callers. Generally, responders acquire enough information so that resources can be provided to the caller. However, this results in inconsistent quantity and quality of information provided across call narratives and is a limitation of this dataset. For example, while some reports were brief (e.g., voicemails), other reports were extensive. As a result, specific incidents of abuse could not be determined from calls that reported very little information. Additionally, calls and messages evaluated for this study were made within a limited 3-year time period. As time passes, more data can be acquired and updates to these findings can be reported, including differences across time periods. Another noteworthy limitation relates to how we defined elder abuse and the specific coding choices we made. As discussed, definitions of elder abuse vary across studies (e.g., inclusion of strangers as was done here, versus only including trusted individuals) and findings may differ as a result. This limits the utility of comparison between studies that utilize different definitions. Our specific coding decisions may have also impacted the findings. For example, we chose to include “alleged abuse by a company or facility” as a classification for the “number of abusers reported” category in order to capture the various relationships that are subsumed under this classification and because this classification reflects a systemic issue with an organization that we felt could not be captured by the other classifications (single abuser, more than one abuser). For example, one call discussed an elderly individual whose condition worsened following entry into a nursing home due to suspected medication errors, neglect by staff, and unhygienic living conditions. This call was classified as “alleged abuse by a company or facility” within the “number of abusers category” because it describes a systemic issue with a nursing home. Under the “relationship to the victim” category, it was classified as “non-family caregiver, medical.” However, another equally valid option would have been to include “abuse by a company or facility” within the “relationship to the victim” category and count these calls as “more than one abuser” in the “number of abusers reported” category. This would undoubtedly change the frequency breakdown of these different categories. Finally, the ratings were made based on each caller’s report. We were unable to substantiate the abuse claims and treated all as equally valid.

Despite these limitations, the present study has notable strengths. It is the first study to explore elder abuse using data from the NCEA resource line, thus providing a unique source of information regarding elder abuse nationally. Findings are in line with other studies that report financial abuse to be the most prevalent type of elder abuse, and that family members are the most common perpetrators across all abuse types. Results highlight the importance of implementing strategies to prevent future abuse in victims, a necessary step towards reducing the public health burden of elder abuse. Studies targeted towards identifying high-risk individuals and understanding additional risk factors will inform elder abuse prevention programs and treatment interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jacqueline Chen and Via Savage for their help with coding the NCEA calls. This work was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California (#HS-17-0047).

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health grants (R01AG055430 to SDH, R01AG060096 to LM and ZDG, and T32 AG000037 to GHW), and the Administration for Community Living grant (90ABRC0001-02-00 to LM), as well as the Department of Family Medicine of the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American journal of public health, 100(2), 292 – 297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker D, Aurelien G, Beatrice M, Capehart A, Gassoumis Z, Gervais Voss P,..., & Phillippi M (2018). NAMRS FFY2016 Background Report. Washington D.C.: Administration for Community Living, U.S> Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Zajac K, Strachan M, Hernandez MA, Kilpatrick DG, & Acierno R (2011). Prevalence and correlates of elder mistreatment in South Carolina: The South Carolina elder mistreatment study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(15), 2947–2972. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs S, Manthorpe J, Tinker A, Doyle M, & Erens B (2009). Mistreatment of older people in the United Kingdom: Findings from the first national prevalence study. Journal of elder abuse & neglect, 27(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1080/08946560802571870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes D, Pillemer K, Caccamise PL, Mason A, Henderson CR Jr, Berman J, . . . Powell M (2015). Prevalence of and risk factors for elder abuse and neglect in the community: a population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1906–1912. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Kulick DB, & Mayer J (1999). Financial exploitation of elders: Analysis of risk factors based on county adult protective services data. Journal of elder abuse & neglect, 10(3-4), 39–62. doi: 10.1300/J084v10n03_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, & Mayer J (2000). Elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation: Risk factors and prevention strategies. Journal of gerontological social work, 33(2), 5–25. doi: 10.1300/J083v33n02_0214628757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comijs HC, Pot AM, Smit JH, Bouter LM, & Jonker C (1998). Elder abuse in the community: prevalence and consequences. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 46(7), 885–888. doi: j.1532-5415.1998.tb02724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X (2005). Medical implications of elder abuse and neglect. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 21(2), 293–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon M, Beck T, & Evans D (2010). A cross-sectional population-based study of elder self-neglect and psychological, health, and social factors in a biracial commnity. Aging and Mental Health, 14, 74–84. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, & Regan SL (2006). The extent and frequency of abuse in the lives of older women and their relationship with health outcomes. The Gerontologist, 46(2), 200–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LS, Avila S, Rizvi T, Partida R, & Friedman D (2017). Physical abuse of elderly adults: victim characteristics and determinants of revictimization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(7), 1420–1426. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Karch D, & Crosby A (2016). Elder abuse surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended core data elements for use in elder abuse surveillance, Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL, & Hafemeister TL (2012). Enhancing the safety of elderly victims after the close of an APS investigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(6), 1223–1239. doi: 10.1177/0886260512468241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL, & Hafemeister TL (2013). Understanding elder abuse. New directions for developing theories of elder abuse occuring in domestic settings. National Institute of Justice Research in Brief. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/241731.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lachs M, & Berman J (2011). Under the radar: New York State elder abuse prevalence study. Prepared by Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, and New York City Department for the Aging; https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, & Pillemer KA (2015). Elder abuse. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(20), 1947–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Williams C, O'brien S, Hurst L, & Horwitz R (1996). Older adults: an 11-year longitudinal study of adult protective service use Archives of internal medicine, 156(4), 449–453. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440040127014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, & Waite LJ (2008). Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(4), S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.S248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon A, Lawson K, Carpiac M, & Spaziano E (2006). Elder abuse and neglect among veterans in Greater Los Angeles: prevalence, types, and intervention outcomes. Journal of gerontological social work, 46(3-4), 187–204. doi: 10.1300/J083v46n03_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueda LA, & Dong X (2011). Elder abuse and self-neglect: I don't care anything about going to the doctor to be honest...Journal of the American Medical Association, 306, 532–540. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse. (1998) The national elder abuse incidence study. Washington, DC: American Public Human Services Association. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro AE, Wilber KH, Yonashiro J, & Homeier DC (2010). Do we really need another meeting? Lessons from the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Foresnsic Center. The Gerontologist, 50, 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris B, Meier D, Goldstein T, Weiss M, & Fein E (1995). Elder abuse and neglect: how to recognize warning signs and intervene. Geriatrics (Basel, Switzerland), 50(4), 47–51; quiz 52-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JC, Burnes DP, Caccamise PL, Mason A, Henderson CR Jr., Wells MT, . . . Lachs MS (2014). Financial exploitation of older adults: a population-based prevalence study. J Gen Intern Med, 29(12), 1615–1623. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2946-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Connolly M-T, Breckman R, Spreng N, & Lachs MS (2015). Elder mistreatment: Priorities for consideration by the White House Conference on Aging. The Gerontologist, 55(2), 320–327. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post L, Page C, Conner T, Prokhorov A, Fang Y, & Biroscak BJ (2010). Elder abuse in long-term care: Types, patterns, and risk factors. Research on aging,32(3), 323–348. doi: 10.1177/0164027509357705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2017). Facts for Features: Hispanic Heritage Month 2017.

- U. S. Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Elder Justice Roadmap. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download [Google Scholar]

- Vilar-Compote M, & Gaitán-Rossi P (2018). Syndemics of severity and frequency of elder abuse: A cross-sectional study in Mexican older females. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, & Wilber KH (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e147–e156. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]