Abstract

We identified developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms among 674 Indigenous adolescents (M age = 11.10, SD = .83 years) progressing from early to late adolescence. Four depressive symptoms trajectories were identified: (1) sustained low, (2) initially low but increasing, (3) initially high but decreasing, and (4) sustained high levels of depressive symptoms. Trajectory group membership varied as a function of gender, pubertal development, caregiver major depression, and perceived discrimination. Moreover, participants in the different trajectory groups were at differential risk for the development of an alcohol use disorder. These results highlight the benefit of examining the development of depressive symptoms and the unique ways that depressive symptoms develop among North American Indigenous youth as they progress through adolescence.

Keywords: Depression, Native Americans, Canadian First Nations, Latent Trajectories

Scholars have suggested that individuals of North American Indigenous background (e.g., Native Americans, Canadian First Nations) are at greater risk for experiencing psychological disorders stemming from their disproportionate experiences with stress and trauma (Manson, Beals, Klein, & Croy, 2005; Stiffman et al., 2007). Despite this suggestion, relatively little empirical effort has been made to understand the development of psychological difficulties among Indigenous groups. The purpose of the present study was to contribute to this limited body of research by examining the ways in which depressive symptoms develop across adolescence among a sample of North American Indigenous youths. Specifically, using a latent class trajectory approach, we identify and describe the qualitatively distinct patterns (i.e., trajectories) of depressive symptoms that our participants followed as they progressed from early to late adolescence. In addition, we considered if membership in distinct depressive symptoms trajectory groups systematically varied as a function of gender, early pubertal development, caregiver history of major depression, and perceived experiences with discrimination during early adolescence. We also examined whether youths who followed specific developmental patterns were at differential risk for developing an alcohol use disorder.

Before describing our study, we discuss studies that have examined depressive experiences among North American Indigenous (hereafter referred to as Indigenous) populations and summarize the results of prior studies that have examined the developmental patterns of depressive symptoms across adolescence. We then outline our predictions regarding the potential role of gender, early pubertal development, caregiver history of major depression, and perceived discrimination during early adolescence in predicting developmental patterns in depressive symptoms. We also describe our prediction regarding the differential risk for developing an alcohol use disorder (AUD) as a function of specific developmental patterns of depressive symptoms.

Depression among North American Indigenous Groups

Scholars have argued that Indigenous populations are at greater risk for experiencing major depression as a result of their disproportionate exposure to stressful life events, such as poverty, substance use and abuse, physical illness, and trauma stemming from a long history of maltreatment (Manson et al., 2005; Stiffman et al., 2007). In line with this argument, data from Waves 1 and 2 of the Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; Hasin & Grant, 2015), and the NESARC 3, indicate that the prevalence of lifetime and past 12-month major depressive disorder (MDD) are higher among U.S. Indigenous adults, relative to their non-Indigenous counterparts.

Other scholars have argued, however, that standardized instruments used to diagnose MDD do not take Indigenous worldviews into consideration and therefore might not be appropriate for use with Indigenous populations (Beals, Manson, Mitchell, Spicer, & AI-SUPERPFP Team, 2003; Gone & Trimble, 2012; Whitbeck, Hartshorn, & Walls, 2014). Indeed, when using culturally-informed adaptations of the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI; Kessler et al., 1998), the prevalence rates of lifetime and past 12-month MDD are lower for Indigenous adolescents and adults in the U.S. (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Mitchell, et al., 2005; Whitbeck et al., 2014; Whitbeck, Hoyt, Johnson, & Chen, 2006; Whitbeck, Yu, Johnson, Hoyt, & Walls, 2008) and Canada (Whitbeck et al., 2014, 2006, 2008) than prevalence rates obtained from epidemiologic studies conducted in the U.S. (e.g., Angold & Costello, 2001; Kessler et al., 1994). These findings highlight the importance of using culturally-informed assessments when working with Indigenous populations, which is an issue we return to in our Discussion. We note that the papers published by (Whitbeck et al., 2014, 2008) relied on the first four waves of data used in our analyses; there are no overlapping analyses.

Measurement issues aside, studies suggest that, relative to their non-Indigenous counterparts, Indigenous youths experience more pronounced negative consequences as a result of mental health problems (e.g., suicidality, substance use; Manson et al., 2005; Stiffman et al., 2007). This evidence highlights a critical need to (a) understand the degree and duration (i.e., developmental patterns) of Indigenous adolescents’ experiences with depressive symptoms, (b) identity factors that increase the risk of experiencing elevated levels of depressive symptoms, and (c) determine whether specific developmental patterns of depressive symptoms have different health-related consequences. We begin addressing these issues with the present study.

Development of Depressive Symptoms across Adolescence

Empirical evidence suggests that, on average, depressive symptoms decrease throughout adolescence (Adkins, Wang, & Elder, 2009; Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002; cf. Vannucci & McCauley Ohannessian, 2018). Empirical studies also show, however, that there is substantial variability in initial levels of (i.e., intercept), and the magnitude and direction of changes in (i.e., slope), adolescent depressive symptoms (e.g., Fleming, Mason, Mazza, Abbott, & Catalano, 2008; Vannucci & McCauley Ohannessian, 2018). In recognizing this variability, scholars have used analytic approaches such as latent class trajectory analysis (LCTA) and growth mixture modeling (GMM) to examine differential developmental patterns (or trajectories) of depressive symptoms among adolescence. LCTA relies on longitudinal data to categorize individuals into trajectory groups based on similarities and differences in changes across time (e.g., increasing, decreasing, and stable levels). GMM extends LCTA by allowing variability in trajectory intercepts and slopes. Both approaches can include covariates (e.g., parental history of depression) to predict the probability of following specific developmental patterns and can be used to predict outcomes (e.g., AUD) as a function of trajectory group membership (for a detailed overview of LCTA and GMM, see Muthén, 2001).

Scholars using these approaches have assessed depressive symptoms in various ways, ranging from brief self-reports (e.g., Chaiton et al., 2013; Costello, Swendsen, Rose, & Dierker, 2008; Cumsille, Martínez, Rodríguez, & Darling, 2015; Repetto, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2004) to extensive, clinically-oriented questionnaires and structured interviews (e.g., Briere, Janosz, Fallu, & Morizot, 2015; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Ellis et al., 2017; Mezulis, Salk, Hyde, Priess-Groben, & Simonson, 2014; Reinke, Eddy, Dishion, & Reid, 2012; Wickrama & Wickrama, 2010; Wu, 2017; Yaroslavsky, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Roberts, 2013). In addition, some studies have focused on the development of depressive symptoms across the entire span of adolescence (Chaiton et al., 2013; Costello et al., 2008; Dekker et al., 2007; Diamantopoulou, Verhulst, & van der Ende, 2011; Ellis et al., 2017; Ferro, Gorter, & Boyle, 2015; Mezulis et al., 2014; Wickrama & Wickrama, 2010; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013) while others have been limited to either early (Brendgen, Wanner, Morin, & Vitaro, 2005; Briere et al., 2015; Cumsille et al., 2015; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Reinke et al., 2012; Sallinen, Rönkä, Kinnunen, & Kokko, 2007) or late (Rodriguez, Moss, & Audrain-McGovern, 2005; Stoolmiller, Kim, & Capaldi, 2005) adolescence.

Despite the differences across studies, four unique developmental trajectories are commonly identified (for reviews, see Musliner et al., 2016; Schubert et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2017). The four trajectories are typically characterized by (a) low depressive symptoms that remain relatively stable across time (sustained low levels, or low), (b) high depressive symptoms that remain relatively stable across time (sustained high levels, or high), (c) high initial levels of depressive symptoms that decrease across time (high-decreasing), and (d) low initial levels of depressive symptoms that increase across time (low-increasing; Briere et al., 2015; Chaiton et al., 2013; Dekker et al., 2007; Diamantopoulou et al., 2011; Ferro et al., 2015; Mezulis et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2005; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013). Importantly, some or all of these patterns have been identified in studies that have identified fewer (e.g., 3; Chaiton et al., 2013; Ferro et al., 2015; Mezulis et al., 2014) or more (e.g., 6; Colman, Ploubidis, Wadsworth, Jones, & Croudace, 2007) trajectories.

As already noted, we are aware of no published studies that have focused on the development of depressive symptoms among Indigenous youths. In order to address this issue, the first goal of the present study was to identify the distinct developmental patterns of depressive symptoms that our sample of Indigenous youths followed as they progressed through adolescence. Given the results of prior studies conducted with non-Indigenous adolescents (see Musliner et al., 2016; Schubert et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2017), we predicted that depressive symptoms in our sample would follow the four developmental patterns described above (hypothesis 1).

Predictors of Depressive Symptom Trajectories

The second goal of our study was to consider whether membership in the depressive symptoms trajectory groups varied as a function of personal, familial, and minority-related factors. In particular, we considered whether girls (vs. boys), early pubertal development, having a primary caregiver with a history of major depression, and higher levels of perceived discrimination during early adolescence (i.e., ages 11–12 years) increased the risk of following developmental patterns characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms.

In general, studies have shown that girls are more likely than boys to show sustained high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence (e.g., Chaiton et al., 2013; Costello et al., 2008; Diamantopoulou et al., 2011; Mezulis et al., 2014). These findings cohere with a wealth of cross-sectional evidence showing that adolescent girls tend to report higher levels of depressive symptoms than adolescent boys (Angold, Erkanli, Silberg, Eaves, & Costello, 2002; Cole et al., 2002; Galambos, Leadbeater, & Barker, 2004). We thus predicted that girls would be more likely than boys to follow a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms (hypothesis 2).

Scholars have shown that early pubertal development increases adolescents’ risk for experiencing psychosocial difficulties (see Ullsperger & Nikolas, 2017), perhaps because they have not yet developed the cognitive and emotional skills necessary to understand and cope with the rapid physical changes they are experiencing (Brooks-Gunn, Petersen, & Eichorn, 1985). Despite arguments that early maturation is primarily distressful for girls (Dick, Rose, Viken, & Kaprio, 2000; Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007), and may even have psychosocial benefits for boys (e.g., Negriff & Susman, 2011; Steinberg & Morris, 2001), meta-analytic evidence does not support this argument (Ullsperger & Nikolas, 2017). Of particular importance to the present study, Mezulis and his colleagues (2014) showed that girls and boys who initiated puberty early were at similar risk for experiencing sustained high levels of depressive symptoms during adolescence. As such, we predicted that early pubertal development (relative to same-gender peers) would increase the risk for experiencing sustained high levels of depressive symptoms (hypothesis 3). Although we did not anticipate differences, we also tested whether gender moderated the early pubertal development effect.

A large body of empirical evidence suggests that having a parent or caregiver with a history of major depression increases the risk for the development of depression during adolescence (Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; Pettit, Olino, Roberts, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 2008). Of specific relevance to the present study, Stoolmiller and colleagues (2005) showed that adolescents who had a caregiver with a history of major depression were more likely to follow a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms. As such, we predicted that adolescents who had a caregiver with a history of major depression (i.e., lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder) would be more likely to follow a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms (hypothesis 4).

No published studies have considered perceptions of discrimination in relation to specific depressive symptoms trajectories. Using latent growth curve modeling, however, Hurd, Varner, Caldwell, and Zimmerman (2014) showed that, on average, depressive symptoms did not change across time among a sample of African American emerging adults, but that perceptions of discrimination positively predicted variability in changes in depressive symptoms. Their results indicated that, at higher levels of perceived discrimination, the growth in depressive symptoms was positive and statically significant. In another study, Stoolmiller and colleagues (2005) showed that adolescents who were exposed to general stressors (e.g., familial negative life events, low family income) were more likely to follow a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms. Given that experiencing discrimination can be stressful (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), we might expect a similar pattern for perceived discrimination. We therefore predicted that perceiving more discrimination during early adolescence would increase the risk for following a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms (hypothesis 5).

Consequence of Depressive Symptoms Trajectory Group Membership

The third goal of the present study was to evaluate whether adolescents who fell into the different depressive symptoms trajectory groups were at differential risk for developing an alcohol use disorder (AUD) during adolescence. It is well-established that major depression and alcohol use disorders often co-occur (Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005), including among Indigenous populations (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Spicer, et al., 2005; Gilder, Wall, & Ehlers, 2004). As such, we predicted that adolescents who followed a developmental trajectory characterized by sustained high levels of depressive symptoms would be at greater risk for developing an AUD during adolescence (hypothesis 6).

Method

Study Design and Participants

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study examining culture-specific risk and resilience factors among Indigenous adolescents conducted from 2002 to 2009 (Whitbeck et al., 2014). The study was designed in partnership with three U.S. American Indian Reservations and four Canadian First Nations Reserves. The participating reservations and reserves share a common cultural tradition and language with only minor regional variations in dialects. Tribal advisory boards at each site were responsible for advising the research team on questionnaire development and study logistics. The interviewers and site coordinators all were approved by advisory boards and were almost exclusively enrolled tribal members; non-tribally enrolled members were primarily spouses of enrolled tribal members. As part of strict confidentiality agreements with the reservations and reserves, the names of the cultural group and participating sites are not provided and no attempts were made to distinguish between participants from the various study locations in our analyses.

Prior to the first wave of data collection the reservations and reserves provided the research team with a list of all families who had a tribally-enrolled child between the ages of 9–13 years and lived on or near (i.e., within 50 miles) the reservations and reserves. An attempt to contact all families was made in order to obtain a representative sample of the communities. For those families who agreed to participate (79.4% of the population), the target adolescent and at least one caregiver were interviewed annually for 8-years. The families were given $40 per participant (i.e., adolescent and caregiver or caregivers) for each wave of the study that they completed. The study was reviewed and approved by the tribal advisory boards and conducted in compliance with the institutional review board at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

At Wave 1 the sample included 674 adolescents (M age = 11.10, SD = .83; 50.3% girls), of which 94.7% completed Wave 2 (50.1% girls), 92.9% completed Wave 3 (49.8% girls), 87.3% completed Wave 4 (50.8% girls), 87.7% completed Wave 6 (50.3% girls), and 77.6% completed Wave 8 (52.9% girls), which are the waves when the data used for the present analyses were collected. At Wave 1, the primary caregivers reported having had an average of 4.35 children (SD = 2.05; M children living at home = 2.56, SD = 1.84) and an average of 5.05 people (SD = 1.87) living in their household. Of the caregivers, 49.9% reported an annual household income below $25,000. In addition, 41.5% reported that they owned their home, 28.3% reported that they rented their home, 9.2% reported living at home rent free, and 2.3% reported living with friends or family.

Measures

The adolescents completed a battery of measures at each wave of the study. The diagnostic interview that was used to obtain the depressive symptoms scores (i.e., symptoms count) and AUD diagnoses was completed at Waves 1, 4, 6, and 8 of the study. Pubertal development and perceived discrimination were assessed at Waves 1, 2, and 3 and primary caregiver history (i.e., lifetime) of major depression was assessed only at Wave 1. The measures were ultimately restructured by age for our analyses, which is described in further detail below.

Importantly, all of the measures used in this study were reviewed by tribal councils on each of the reservations and reserves in order to verify that they were culturally appropriate. For the diagnostic measures, the wording of some of the items were modified based on feedback from the tribal councils and consultation with the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) Team, who used a similar culturally-informed approach to assess psychiatric disorder among members of two U.S. Indigenous tribal groups (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Spicer, et al., 2005). No changes were made to any of the non-diagnostic measures used for the analyses we conducted. All of the measures were considered to be culturally-appropriate and approved for use by the tribal councils.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the major depression module of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). The DISC-IV is a structured diagnostic interview designed to be administered by non-clinicians, and may be used to provide diagnoses of major depression following the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). The major depression module includes 21 items to assess the 9 DSM-IV-TR major depression criteria, including (a) depressed mood (2 items), (b) diminished interest or pleasure (1 item), (c) weight disturbances (4 items), (d) sleep difficulties (2 items), (e) psychomotor changes (2 items), (f) fatigue (2 items), (g) worthlessness (2 items), (h) diminished ability to think or concentrate (3 items), and (i) recurrent thoughts of death (3 items). For the items, participants were asked to indicate whether they had each of the experiences during the last year, using response options of no (coded as 0) and yes (coded as 1). For those criteria that were assessed with more than 1 item, participants received a score of 1 if they endorsed any of the relevant items, resulting in 9 dichotomously scored variables. Composite depressive symptoms scores were obtained by computing the sum of the 9 items, with higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms.

Diagnosis of lifetime AUD was obtained using the AUD module from the DISC-IV (Shaffer et al., 2000). We used the standardized DISC-IV scoring algorithm, which provides diagnoses of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence as outlined in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000). In order to be more consistent with the 5th edition of the DSM (DSM-5; APA, 2013), we combined the abuse and dependence variables into a single AUD variable. Participants who met criteria for lifetime AUD were given a score of 1 and the remaining participants were given a score of 0.

Pubertal development was measured at Waves 1–3 using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). The PDS is a self-report questionnaire that includes items regarding changes in height, body hair and skin condition. Additional sex-specific items include changes in breast size and menarche for females and voice changes and appearance of facial hair for males. Except for the menarche question, which was answered using a no (coded as 1) and yes (coded as 4) response, the response options for the items included (1) has not yet started, (2) has barely stated, (3) has definitely started, and (4) seems finished.

In order to obtain an early pubertal development variable, we first created scale scores by computing the sum of the item responses. We then recoded the scale scores such that participants in the top 25th percentile of the sample were assigned a score of 1 (further along in pubertal development thus indicating earlier pubertal development) while the remaining participants were assigned a score of 0. We computed the early pubertal development variable separately for boys and girls; thus, the final scores reflect early pubertal development relative to peers of the same gender.

Perceived discrimination was assessed at Waves 1–3 using a modified version of the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). The items were modified to reflect perceptions of discrimination based on membership in the cultural group of the participants. Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they had experienced 11 common forms of discrimination during the past year (e.g., treated badly, called names, ignored because of one’s cultural heritage). Responses were provided on a 3-point scale, anchored by 1 (never) and 3 (always), and composite scores were obtained by computing the average of the item responses.

Caregiver history of major depression was assessed at Wave 1 using the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM CIDI; Kessler et al., 1994), which has been used by the World Health Organization (WHO, 1990). The UM-CIDI is a structured diagnostic interview that may be administered by trained, non-clinician interviewers. A scoring algorithm similar to the one used by the AI-SUPERPFP team (see Beals et al., 2005) was used in order to obtain DSM-III-R-based (APA, 1987) diagnoses of lifetime MDD (for details, see Whitbeck et al., 2014). Caregivers who had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD were given a score of 1 and the remaining caregivers were given a score of 0. Of the primary caregivers at Wave 1, 20.3% were identified as having experienced major depression at some point in their lives.

Data Restructuring

We restructured the depressive symptoms variables by age groups, which included 11–12 years, 13–14 years, 15–16 years, and 17–18 years. Because the diagnostic measure was not completed at all waves, no data on depressive symptoms or alcohol use disorder were available at ages 11–12 for the adolescents who were 10 years old at baseline and no data on depressive symptoms or alcohol use disorder were available at ages 13–14 for the adolescents who were 12 years old at baseline. Because these data are missing as a result of the study design, the pattern of missingness can be considered missing at random (Graham, Taylor, Olchowski, & Cumsille, 2006; Little & Rubin, 2002), which allowed us to obtain unbiased parameter estimates for our analytic models using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation (see Enders, 2010). We should note that we attempted to conduct our analyses based on data that were restructured by individual years of age (i.e., ages 11, 12, 13, etc.). This approach, however, lead to unresolvable convergence issues due to sparse data at several ages. Obtaining age-equivalent reports for perceived discrimination and early pubertal development required us to rely on the adolescent data provided at age 12, as the relevant measures were completed by all of the adolescents at this age. We thus used the Wave 3 data for the adolescents who were 10 years old at baseline, Wave 2 data for the adolescents who were 11 years old at baseline, and Wave 1 data for the adolescents who were 12 years old at baseline. Restructuring was not required for gender, which remained constant throughout the study, or caregiver history of major depression, which was only assessed at Wave 1.

Analytic Strategy

We conducted our analyses within Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015) using FIML estimation with Monte Carlo integration (in Mplus, type = mixture; algorithm = integration; integration = montecarlo). We estimated LCTA models with latent trajectory classes ranging from 2 to 6, each of which included fixed intercept, linear, and quadratic trajectory parameters. We elected to use LCTA because we were specifically interested in examining general patterns of depressive symptoms, rather than variability within trajectory classes. We evaluated the fit of the models on a comparative basis (e.g., 2 vs. 3 trajectory classes) using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Bozdogan, 1987), Consistent Akaike Information Criterion (CAIC; Bozdogan, 1987), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), and Sample-size Adjusted BIC (ABIC; Sclove, 1987). Information criteria values modify log-likelihood values in order to take model complexity into account with lower values indicative of better model fit (Masyn, 2013). Simulation studies suggest that the BIC and ABIC perform especially well across many data situations (e.g., with covariates, without covariates) with larger sample sizes ( e.g., n > 500–1,000; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007; Tofighi & Enders, 2008). These studies also suggest that the CAIC performs well with larger sample sizes, although not as consistently as the BIC and ABIC, while the AIC often performs less well, with the potential exception of very specific data conditions (Hu, Leite, & Gao, 2017). As such, we relied most heavily on the BIC, ABIC, and CAIC in selecting our final model, and report AIC for the sake of being comprehensive.

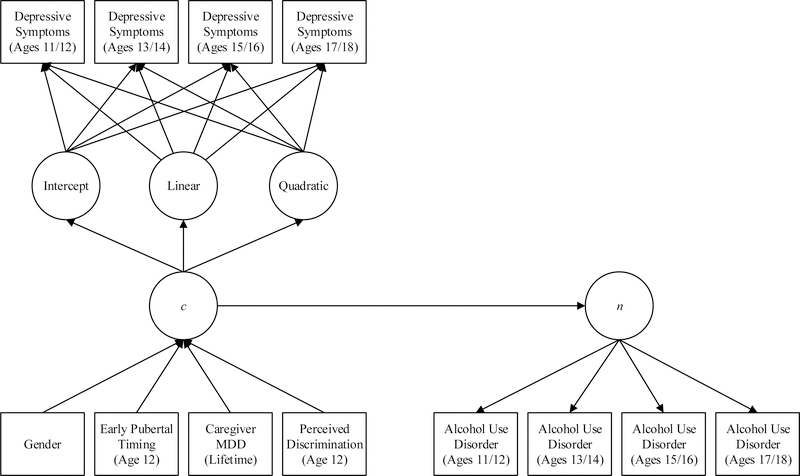

Based on data simulations, Li and Hser (2011) concluded that the enumeration of latent classes can be biased when relevant covariates are not included in the enumeration process. Because of this, we estimated our models with the covariates (e.g., early pubertal development) and outcome (i.e., risk for AUD) included. As shown in Figure 1, gender, early pubertal development, caregiver history of MDD, and perceived discrimination were included as predictors of membership in the latent trajectory classes and the latent trajectory classes served as a predictor of a latent lifetime AUD hazard function (using discrete-time survival analysis [DTSA]). Lifetime AUD at each wave served as indicators of the latent hazard function, with all loadings fixed to 1. Given these specifications, the LCTA classes served as a time-invariant predictor of the general risk for developing an AUD during adolescence. For further details on DTSA within Mplus, readers are referred to Muthén and Masyn (2005). For further details on our overall analytic approach, readers are referred to Malone et al. (2010).

Figure 1.

Latent class trajectory/discrete time survival model

Note. MDD = major depressive disorder; c = latent class; n = general hazard function.

Results

Identifying Latent Trajectory Classes

The AIC, CAIC, BIC, and ABIC for the 2–6 latent trajectory models are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, the CAIC, BIC, and ABIC favored a 4-class solution whereas the AIC favored a 6-class solution. Given that we predicted a 4-class solution, the convergence of the CAIC, BIC, and ABIC, and evidence that the AIC does not perform as well as the remaining information criteria (see Analytic Strategy), we selected the 4-class solution as our final model.

Table 1.

Information criteria values for latent class trajectory models

| Model | AIC | CAIC | BIC | ABIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Class Model | 10444.18 | 10480.74 | 10534.41 | 10470.91 |

| 3 Class Model | 10383.73 | 10436.74 | 10514.57 | 10422.49 |

| 4 Class Model | 10324.54 | 10394.00 | 10495.99 | 10375.33 |

| 5 Class Model | 10318.61 | 10404.52 | 10530.66 | 10381.43 |

| 6 Class Model | 10313.52 | 10415.89 | 10566.18 | 10388.37 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; CAIC = Consistent Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; ABIC = Sample-size Adjusted BIC; lowest values are in bold.

Latent Trajectory Classes

The patterns for the four latent trajectory classes are shown in Figure 2; the unstandardized intercepts, linear, and quadratic parameters (with standard errors and two-tailed probability values) are provided in Table 2. The first trajectory, which included 36.9% of the sample, was characterized by relatively low levels of depressive symptoms that decreased slightly across time (hereafter referred to as the low depressive symptoms group). The second trajectory, which included 7.6% of the sample, was characterized by low initial levels of depressive symptoms that sharply increased after ages 13–14 years (hereafter referred to as the low-increasing depressive symptoms group). The third trajectory, which included 34.2% of the sample, was characterized by high initial levels of depressive symptoms that increased slightly between ages 11–12 and 13–14 years, but steadily decreased thereafter (hereafter referred to as the high-decreasing depressive symptoms group). The final trajectory, which included 21.4% of the sample, was characterized by high levels of depressive symptoms that were relatively consistent across time (hereafter referred to as the high depressive symptoms group).

Figure 2.

Final latent class trajectories

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for final latent trajectory classes

| Trajectory Classes/Parameters | b | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 248; 36.9%) | |||

| Intercept | 2.82 | .22 | <.01 |

| Linear term | −.73 | .28 | <.01 |

| Quadratic term | .05 | .08 | .58 |

| Low-Increasing (n = 51; 7.6%) | |||

| Intercept | 2.57 | .71 | <.01 |

| Linear term | −.81 | .75 | .28 |

| Quadratic term | .56 | .20 | <.01 |

| High-Decreasing (n = 230; 34.2%) | |||

| Intercept | 5.38 | .24 | <.01 |

| Linear term | .45 | .36 | .21 |

| Quadratic term | −.51 | .11 | <.01 |

| High (n = 144; 21.4%) | |||

| Intercept | 5.46 | .23 | <.01 |

| Linear term | 1.03 | .33 | <.01 |

| Quadratic term | −.25 | .10 | .01 |

Note. b = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error;

p = two-tail probability value.

Predicting Membership in Trajectory Groups

The associations from gender, early pubertal development, perceived discrimination, and caregiver history of MDD to latent trajectory class membership were estimated using multinomial logistic regression. All possible comparisons for each of the predictors are provided in Table 3. We focus on the general pattern of the findings, as indicated by the unstandardized (logit) coefficients, and report odds ratios for descriptive purposes. To facilitate interpretation of the results, perceived discrimination was standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. The unstandardized coefficients thus represent the expected logit change for a one standard deviation increase in perceived discrimination while the odds ratios represent the expected change in odds for a one standard deviation increase in perceived discrimination. Gender (0 = boys, 1 = girls), early pubertal development (0 = not early, 1 = early), and caregiver MDD (0 = no history of MDD, 1 = history of MDD) were included as dummy-codes. For descriptive purposes, the percent of participants within each trajectory group that were girls or boys, evidenced early pubertal development, and had a caregiver with a history of depression are provided in Table 4. Also provided in the table are the within group means for perceived discrimination and the distribution of the girls and boys (separately) across the trajectory groups (i.e., within gender).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression results

| Low (0) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Increasing (1) |

High-Decreasing (1) |

High (1) |

||||||||||

| b | SE | OR | p | b | SE | OR | p | b | SE | OR | p | |

| Gender | .91 | .40 | 2.50 | .02 | 1.21 | .30 | 3.35 | <.01 | 1.54 | .28 | 4.65 | <.01 |

| Early Pubertal Development | .68 | .46 | 1.97 | .14 | .80 | .33 | 2.21 | .02 | .85 | .31 | 2.33 | <.01 |

| Caregiver Major Depression | −.22 | .50 | .80 | .65 | −.18 | .36 | .83 | .61 | .47 | .30 | 1.60 | .12 |

| Perceived Discrimination | .46 | .29 | 1.58 | .12 | .99 | .22 | 2.70 | <.01 | 1.02 | .21 | 2.79 | <.01 |

| General Hazard Function | .75 | .39 | 2.12 | .06 | .99 | .28 | 2.69 | <.01 | 2.15 | .25 | 8.58 | <.01 |

| Low-Increasing (0) |

High-Decreasing (0) |

|||||||||||

| High-Decreasing (1) |

High (1) |

High (1) |

||||||||||

| b | SE | OR | p | b | SE | OR | p | b | SE | OR | p | |

| Gender | .29 | .51 | 1.34 | .48 | .62 | .42 | 1.86 | .14 | .33 | .28 | 1.39 | .25 |

| Early Pubertal Development | .12 | .45 | 1.13 | .79 | .17 | .46 | 1.18 | .71 | .05 | .29 | 1.05 | .86 |

| Caregiver Major Depression | .04 | .52 | 1.04 | .94 | .70 | .51 | 2.00 | .18 | .65 | .32 | 1.92 | .04 |

| Perceived Discrimination | .54 | .26 | 1.71 | .04 | .57 | .26 | 1.77 | .03 | .03 | .11 | 1.03 | .77 |

| General Hazard Function | .24 | .38 | 1.27 | .52 | 1.40 | .37 | 4.06 | <.01 | 1.16 | .22 | 3.19 | <.01 |

Note. b = logit coefficient; SE = standard error; OR = odds ratio; p = two-tailed probability value; gender (0 = boys, 1 = girls), early pubertal development (0 = not early, 1 = early) and caregiver major depression (0 = no history of major depressive disorder, 1 = history of major depressive disorder) are dummy coded; perceived discrimination is standardized with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1; (0) = reference group, (1) = comparison group for multinomial logistic regression comparisons.

Table 4.

Estimated percentages/means (standard deviations) within latent trajectory classes (unless otherwise noted)

| Low (n = 248) |

Low-Increasing (n = 51) |

High-Decreasing (n = 230) |

High (n = 144) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (within gender) | ||||

| Boys (n = 335) | 50.45% | 6.57% | 27.46% | 15.52% |

| Girls (n = 338) | 23.37% | 8.58% | 40.83% | 27.22% |

| Gender (within classes) | ||||

| Boys (n = 335) | 68.15% | 43.14% | 40.00% | 36.11% |

| Girls (n = 338) | 31.85% | 56.86% | 60.00% | 63.89% |

| Early Pubertal Development (n = 179) | 16.53% | 29.41% | 32.61% | 33.33% |

| Caregiver Major Depressive Disorder (n = 135) | 20.16% | 17.65% | 13.91% | 30.56% |

| Perceived Discrimination | .12 (.14) | .17 (.20) | .31 (.28) | .29 (.31) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder (n = 221) | 12.90% | 27.45% | 32.61% | 69.44% |

Note. The within gender values represent the percentage of girls and the percentage of boys who were categorized into the four classes (comparisons should be made across rows); the within classes values represent the percentage of girls and boys within each class separately (comparisons should be made within classes); the perceived discrimination values represent the means (standard deviations) within each class; the remaining values represent the percentage of participants within each class that were coded as 1 (i.e., evidence of early pubertal development, having a caregiver with a history of major depressive disorder, and having been diagnosed with an AUD at some point during adolescence).

As shown in Table 3, girls were more likely than boys to be in the low-increasing, high-decreasing, and high depressive symptoms groups than in the low depressive symptoms group. In addition, adolescents with early pubertal development were more likely than their counterparts to be in the high-decreasing and high depressive symptoms groups than in the low depressive symptoms group. Moreover, adolescents who had a caregiver with a history of MDD were more likely than their counterparts to be in the high depressive symptoms group than in the high-decreasing depressive symptoms group. Further, higher levels of perceived discrimination increased the risk for being in the high-decreasing and high depressive symptoms groups, relative to the low and low-increasing depressive symptoms groups.

We considered whether gender moderated the early pubertal development effects by entering a gender by early pubertal development interaction term into our model. In order to be comprehensive, we also considered potential interactions between gender and caregiver MDD and between gender and perceived discrimination. None of the interactions were statistically significant. This was the case when the interaction terms were entered individually or simultaneously. Notably, the trajectory class enumeration did not differ when the interactions were included in the model; that is, a four-class solution was favored when the interaction terms were or were not included.

We conducted secondary analyses for boys and girls separately in order to consider whether any important gender differences in trajectory classes (i.e., number and patterns), and predictors of membership in the trajectory groups, were obscured by combining the sample in our primary analyses. The number and pattern of the final trajectories for boys and girls were similar to those of our primary analyses. The only notable difference was that the low-increasing and high-decreasing trajectories were more linear for girls than for boys, suggesting that the incline and decline in depressive symptoms occurred slightly earlier for girls. More importantly, in predicting membership in the latent trajectory groups, the pattern of results was similar for girls and boys, and did not substantively differ from the results of our primary analyses. The most notable difference was that some of the significant effects identified in our primary analyses approached, but fell short of, statistical significance for our gender stratified models (i.e., ps = .06-.15), which could be expected due to decreased statistical power resulting from the drop in sample size (i.e., from 674 for the full sample to 339 for girls and 335 for boys).

Risk for AUD

An estimated 221 adolescents (32.8% of the sample) were diagnosed with AUD by the time they were 17–18-years-old. Of these adolescents, 32 were in the low depressive symptoms group (12.9% of adolescents within that class), 14 were in the low-increasing depressive symptoms group (27.5% of adolescents within that class), 75 were in the high-decreasing depressive symptoms group (32.6% of adolescents within that class), and 100 were in the high depressive symptoms group (69.4% of adolescents within that class).

The general risk for developing an AUD during adolescence was modeled as a logistic function of the trajectory groups. The results for all group comparisons are provided at the bottom of Table 3. As can be seen, adolescents in the high depressive symptoms group were at greater risk for developing an AUD than were adolescents in the remaining groups. In addition, adolescents in the high-decreasing depressive symptoms group were at greater risk than adolescents in the low depressive symptoms group for developing an AUD. Finally, adolescents in the low-increasing depressive symptoms group were at slightly greater risk for developing an AUD than adolescents in the low depressive symptoms group, although this effect fell short of statistical significance by a value of .01.

Discussion

We found four distinct trajectory (i.e., developmental) patterns of depressive symptoms among our sample of Indigenous youths as they progressed through adolescence. The specific trajectory patterns (i.e., low, low-increasing, high, and high-decreasing) were largely consistent with several prior studies conducted with non-Indigenous youths (Brendgen et al., 2005; Costello et al., 2008; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Reinke et al., 2012; Stoolmiller et al., 2005) and support our first hypothesis. In addition, as predicted, girls (relative to boys; hypothesis 2), adolescents who showed earlier signs of pubertal development at the age of 12 (hypothesis 3), adolescents with a caregiver who had prior experiences with MDD (based on assessments at Wave 1; hypothesis 4), and adolescents who perceived higher levels of discrimination at age 12 (hypothesis 5) were at greater risk for experiencing sustained high levels of depressive symptoms. Finally, consistent with our final hypothesis, youths who experienced sustained high levels of depressive symptoms were most likely to develop an AUD during adolescence.

Our gender, pubertal development, and caregiver MDD findings are consistent with prior studies conducted with non-Indigenous adolescents (e.g., Chaiton et al., 2013; Costello et al., 2008; Mezulis et al., 2014; Stoolmiller et al., 2005), and suggest that being a girl, experiencing earlier pubertal development, and having a caregiver with a history of MDD may represent general (as opposed to group-specific) risk factors. Our results for perceived discrimination are particularly noteworthy as this is the first study to consider whether early perceptions of discrimination (in our case, at age 12) are associated with specific developmental patterns of depressive symptoms. In addition to the finding that perceived discrimination increased the risk for experiencing sustained high levels of depressive symptoms, we found that adolescents who perceived higher levels of discrimination at age 12 were at increased risk for experiencing elevated levels of depressive symptoms during both early (i.e., high-increasing) and late (i.e., low-increasing) adolescence. These results suggest that the mental health of Indigenous adolescents may be improved by addressing the ways in which they understand and respond to perceived experiences with discrimination.

Research among ethnic minority adolescents suggests that teaching youths (via direct and indirect messages) to take pride in their ethno-cultural heritage, and ways to effectively cope with discrimination, can reduce the negative psychosocial consequences associated with their perceived experiences with discrimination (Hughes et al., 2006). Correspondingly, teaching Indigenous adolescents to take pride in their cultural heritage and ways to effectively cope with discrimination may be an especially useful way to reduce the negative psychosocial consequences associated with perceived discrimination. Such teaching can take place in the home or by practitioners already working with Indigenous adolescents who are experiencing psychological difficulties. This also can be integrated into existing prevention and intervention programs aimed at improving the psychosocial well-being of Indigenous adolescents, thus providing a cost-effective way to increase the efficacy of such programs. Importantly, addressing the ways in which Indigenous adolescents experience and respond to discrimination does not require reductions in intergroup bias or systematic forms of discrimination, which are social problems that individual group members may have little control over.

Two additional findings warrant further discussion. First, as already noted, adolescents who experienced earlier pubertal development were more likely than their counterparts to be in the high and high-decreasing depressive symptoms classes than in the low depressive symptoms class, which replicates the findings of Mezulis and colleagues (2014). This finding is at odds with common arguments that early maturing girls are at greater risk for emotional problems (Dick et al., 2000; Mendle et al., 2007) while there may be psychosocial benefits for early maturing boys (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). This finding is consistent, however, with meta-analytic evidence showing that gender does not moderate the early pubertal development effect (Ullsperger & Nikolas, 2017).

Second, our four-trajectory solution was not surprising as it is consistent with several studies conducted with non-Indigenous youths (e.g., Brendgen et al., 2005; Costello et al., 2008; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Reinke et al., 2012; Stoolmiller et al., 2005). The distribution of our sample into the four trajectory groups, however, is cause for concern. Meta-analytic estimates suggest that 12% of youths in prior studies experienced elevated levels of depressive symptoms at some point during childhood and adolescence (i.e., high, high-decreasing, or low-increasing levels of depressive symptoms; Shore et al., 2017). This is dramatically lower than the 63% of our participants who fell into the same categories. In fact, the percentage of our participants who showed sustained high levels of depressive symptoms (21.4%) far exceeds the percentage of participants in prior studies who have experienced any elevated levels of depressive symptoms. This is consistent with prior arguments that Indigenous populations are likely to experience higher rates of depression owing to their disproportionate exposure to stressors (Manson et al., 2005; Stiffman et al., 2007), but is inconsistent with evidence showing that, relative to general population estimates, experiences of MDD is not more pronounced among Indigenous groups (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Mitchell, et al., 2005; Whitbeck et al., 2008).

One potential explanation for the inconsistency is that existing diagnostic measures, even when modified to be more culturally appropriate (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Mitchell, et al., 2005; Whitbeck et al., 2014), may not adequately capture the ways in which depression (or a mental state akin to the Western notion of depression) manifests among members of Indigenous groups. For example, evidence from different Indigenous groups suggests that expressions of sadness are discouraged (Miller & Schoenfeld, 1971), notions such as guilt may carry different meanings than they do within Western cultures (Manson, Shore, & Bloom, 1985), and loneliness may be a particularly strong indicator of psychological distress (O’Nell, 2004). As such, symptoms related to the manifestation of depression among members of Indigenous groups may not be adequately captured by DSM-based diagnostic measures, including the one used in our study. This would help to explain why a large percentage of our sample showed elevated levels of depressive symptoms despite the relatively low rates of MDD reported in prior studies (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Mitchell, et al., 2005; Whitbeck et al., 2006), including studies that relied on the same data used for our analyses (Whitbeck et al., 2014, 2008).

Whether existing diagnostic measures based on Western notions of depression are acceptable for use with Indigenous groups requires further theoretical, conceptual, and empirical attention (Manson et al., 1985). It is nonetheless difficult to construe the vast majority of the experiences tapped by existing MDD measures (e.g., diminished interest or pleasure in doing things, insomnia or hypersomnia) as anything other than negative. As such, adolescents in our sample with higher depressive symptom scores undoubtedly experienced more psychological distress. This is empirically substantiated by our finding that adolescents who experienced sustained high levels of depressive symptoms had the greatest risk of developing an AUD. While our analytic approach (based on our research questions) did not allow us to consider the possibility of reverse or reciprocal causality (between depressive symptoms and AUD), the fact that depression appears to be a significant problem for the Indigenous adolescents in our sample, and perhaps Indigenous adolescents in general, remains.

Strengths and Limitations

Our results provide initial insight into the unique developmental patterns of depressive symptoms that Indigenous youths follow as they progress through adolescence, which is an important step in further understanding the etiology of depression among this underserved group. In addition, our findings shed light on factors that increase the risk for following potentially problematic patterns of depressive symptoms. Our use of longitudinal data that covered the entire span of adolescence is one particular strength to our study. Among other things, our data allowed us to consider quadratic developmental patterns, which were important for accurately describing the development of depressive symptoms for a large portion of our sample (i.e., 3 out of 4 trajectory groups had statistically significant quadratic parameters).

An additional strength of the present study was our use of a clinically-oriented instrument to assess depressive symptoms. Specifically, while perhaps imperfect for members of Indigenous groups, the symptom counts we used were based on well-established symptoms of MDD outlined in the DSM-IV-TR (and DSM-5). Considering that the diagnostic cutoff for major depression is experiencing five or more of the symptoms, it would appear that, potential measurement issues aside, a large percentage of the youths in our sample (63.1%) presented at least sub-threshold levels of depressive symptoms at some point during adolescence. Finally, our finding that higher levels of perceived discrimination increased the risk for following a developmental trajectory characterized by elevated levels of depressive symptoms at some point during adolescence suggest that early experiences with discrimination may have short- and long-term psychological consequences for Indigenous youths.

The fact that we obtained nearly 80% of our target population (i.e., Indigenous adolescents between the ages of 10 and 12 who lived on or near their cultural group’s reservation or reserve in the US and Canada) represents another important strength to our study. At the same time, our sample included adolescents from a single cultural group. While there are some similarities across Indigenous populations, there also are important differences (e.g., in traditional and contemporary beliefs, values, and practices). As such, whether our results generalize to Indigenous adolescents from other cultural groups remains to be seen.

Another drawback of our study is that we collected data on depressive symptoms at only four times across eight years, with analytic limitations requiring us to consider two-year age intervals, thus restricting our ability to examine more nuanced fluctuations in depressive symptoms. We are not sure that our results would have differed had we collected data in shorter intervals given that the analytic model we used focuses on general patterns of change and stability across time. Ultimately, however, whether there are important fine-grained details regarding the development of depressive symptoms across adolescence for Indigenous youths is an empirical question that needs to be considered using data collected in briefer intervals.

Implications and Conclusion

Our study has a number of implications. For example, practitioners who aim to reduce the number of Indigenous adolescents that experience psychological distress may find it especially beneficial to allocate a larger share of their resources to adolescents who are at greater risk for experiencing elevated levels of depressive symptoms (e.g., early matures). Other important implications have already been discussed (e.g., potentially reducing psychological distress by changing the ways in which Indigenous adolescents make sense of and respond to discrimination; psychological distress potentially experienced by a large number of Indigenous youths), which we will not repeat here in order to avoid redundancies. There is one exception, however, which we believe is a particularly important take-away message of our study. Specifically, our results highlight a critical need for scholars to take Indigenous worldviews into consideration when studying psychological distress – including the antecedents and consequences of psychological distress – among North American Indigenous populations. This issue has been discussed for several decades now (e.g., Dillard & Manson, 2013; Manson, Bechtold, Novins, & Beals, 1997; Manson et al., 1985; Sundararajan, Misra, & Marsella, 2013; Thrane, Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Shelley, 2004) but has yet to be adequately addressed within the psychological literature.

References

- Adkins DE, Wang V, & Elder GH (2009). Structure and Stress: Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms across Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Social Forces, 88, 31–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition: DSM-III-R; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, & Costello EJ (2001). The epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents In The depressed child and adolescent, 2nd ed (pp. 143–178). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511543821.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, Silberg J, Eaves L, & Costello EJ (2002). Depression Scale Scores in 8–17-year-olds: Effects of Age and Gender. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 43, 1052–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P, & AI-SUPERPFP Team. (2003). Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 27, 259–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Simpson S, & Spicer P (2005). Prevalence of Major Depressive Episode in Two American Indian Reservation Populations: Unexpected Findings With a Structured Interview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1713–1722. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, & Mitchell CM (2005). Prevalence of DSM-IV Disorders and Attendant Help-Seeking in 2 American Indian Reservation Populations. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 99–108. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogan H. (1987). Model selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika, 52, 345–370. 10.1007/BF02294361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Wanner B, Morin AJS, & Vitaro F. (2005). Relations with parents and with peers, temperament, and trajectories of depressed mood during early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 579–594. 10.1007/s10802-005-6739-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere FN, Janosz M, Fallu J-S, & Morizot J. (2015). Adolescent Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms: Codevelopment of Behavioral and Academic Problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57, 313–319. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, & Eichorn D. (1985). The study of maturational timing effects in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 149–161. 10.1007/BF02090316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton M, Contreras G, Brunet J, Sabiston CM, O’Loughlin E, Low NCP, … O’Loughlin J. (2013). Heterogeneity of depressive symptom trajectories through adolescence: Predicting outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 96–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacquez FM, & Maschman TL (2002). Individual Differences in the Emergence of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Longitudinal Investigation of Parent and Child Reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman I, Ploubidis GB, Wadsworth MEJ, Jones PB, & Croudace TJ (2007). A Longitudinal Typology of Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Over the Life Course. Biological Psychiatry, 62, 1265–1271. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello DM, Swendsen J, Rose JS, & Dierker LC (2008). Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 173–183. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumsille P, Martínez ML, Rodríguez V, & Darling N. (2015). Parental and individual predictors of trajectories of depressive symptoms in Chilean adolescents. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15, 208–216. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Ferdinand RF, van Lang NDJ, Bongers IL, van der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2007). Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence: gender differences and adult outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 657–666. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou S, Verhulst FC, & van der Ende J. (2011). Gender differences in the development and adult outcome of co-occurring depression and delinquency in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 644–655. 10.1037/a0023669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Rose RJ, Viken R. j., & Kaprio J. (2000). Pubertal Timing and Substance Use: Associations Between and Within Families Across Late Adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 36, 180–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard DA, & Manson SM (2013). Assessing and Treating American Indian and Alaska Native People In Paniagua FA & Yamada A-M (Eds.), Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health (Second Edition) (pp. 283–303). San Diego: Academic Press; 10.1016/B978-0-12-394420-7.00015-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, & Ratelle CF (2014). Attachment security to mothers and fathers and the developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms in adolescence: which parent for which trajectory? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 641–654. 10.1007/s10964-013-0029-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RER, Seal ML, Simmons JG, Whittle S, Schwartz OS, Byrne ML, & Allen NB (2017). Longitudinal Trajectories of Depression Symptoms in Adolescence: Psychosocial Risk Factors and Outcomes. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48, 554–571. 10.1007/s10578-016-0682-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro MA, Gorter JW, & Boyle MH (2015). Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms in Canadian Emerging Adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 2322–2327. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, & Catalano RF (2008). Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 22, 186–197. 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, & Barker ET (2004). Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, & Martin C. (2002). Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 79–95. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Wall TL, & Ehlers CL (2004). Comorbidity of Select Anxiety and Affective Disorders With Alcohol Dependence in Southwest California Indians. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 1805–1813. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000148116.27875.B0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health: Diverse Perspectives on Enduring Disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 131–160. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, & Cumsille PE (2006). Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 11, 323–343. 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih JH, & Brennan PA (2004). Intergenerational transmission of depression: test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 511–522. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1097–1106. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, & Grant BF (2015). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: Review and summary of findings. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 1609–1640. 10.1007/s00127-015-1088-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Leite WL, & Gao M. (2017). An evaluation of the use of covariates to assist in class enumeration in linear growth mixture modeling. Behavior Research Methods, 49, 1179–1190. 10.3758/s13428-016-0778-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2014). Does Perceived Racial Discrimination Predict Changes in Psychological Distress and Substance Use Over Time? An Examination among Black Emerging Adults. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1910–1918. 10.1037/a0036438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, & Walters EE (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, … Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 51, 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen H-U, Abelson JM, Mcgonagle K, Schwarz N, Kendler KS, … Zhao S. (1998). Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US national comorbidity survey (NCS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 33–55. 10.1002/mpr.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The Schedule of Racist Events: A Measure of Racial Discrimination and a Study of Its Negative Physical and Mental Health Consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144–168. 10.1177/00957984960222002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, & Hser Y-I (2011). On Inclusion of Covariates for Class Enumeration of Growth Mixture Models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 266–302. 10.1080/00273171.2011.556549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data (2nd ed.). Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- Malone PS, Van Eck K, Flory K, & Lamis DA (2010). A mixture-model approach to linking ADHD to adolescent onset of illicit drug use. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1543–1555. 10.1037/a0020549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, & Croy CD (2005). Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 851–859. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Bechtold DW, Novins DK, & Beals J. (1997). Assessing Psychopathology in American Indian and Alaska Native Children and Adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 1, 135–144. 10.1207/s1532480xads0103_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Shore JH, & Bloom JD (1985). The Depressive Experience in American Indian Communities: A challenge for Psychiatric Theory and Diagnosis In Kleinman A. & Good BJ (Eds.), Culture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and Disorder (1st ed, pp. 331–368). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masyn K. (2013). Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling. In The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2 (pp. 551–611). [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Turkheimer E, & Emery RE (2007). Detrimental Psychological Outcomes Associated with Early Pubertal Timing in Adolescent Girls. Developmental Review : DR, 27, 151–171. 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis A, Salk RH, Hyde JS, Priess-Groben H. a., & Simonson JL (2014). Affective, Biological, and Cognitive Predictors of Depressive Symptom Trajectories in Adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 539–550. 10.1007/s10802-013-9812-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SI, & Schoenfeld LS (1971). Suicide Attempt Patterns Among the Navajo Indians. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 17, 189–193. 10.1177/002076407101700303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musliner KL, Munk-Olsen T, Eaton WW, & Zandi PP (2016). Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: Patterns, predictors and outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 199–211. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. (2001). Latent Variable Mixture Modeling In Marcoulides GA & Schumacker RE (Eds.), New Developments and Techniques in Structural Equation Modeling (1 edition, pp. 1–33). Mahwah, N.J: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Masyn K. (2005). Discrete-Time Survival Mixture Analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 30, 27–58. 10.3102/10769986030001027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus User’s Guide. 8th Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, & Susman EJ (2011). Pubertal Timing, Depression, and Externalizing Problems: A Framework, Review, and Examination of Gender Differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 717–746. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00708.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nell TD (2004). Culture and Pathology: Flathead Loneliness Revisited. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28, 221–230. 10.1023/B:MEDI.0000034412.24293.bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, & Boxer A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117–133. 10.1007/BF01537962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit JW, Olino TM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, & Lewinsohn PM (2008). Intergenerational transmission of internalizing problems: effects of parental and grandparental major depressive disorder on child behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 640–650. 10.1080/15374410802148129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke W, Eddy J, Dishion T, & Reid J. (2012). Joint Trajectories of Symptoms of Disruptive Behavior Problems and Depressive Symptoms During Early Adolescence and Adjustment Problems During Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1123–1136. 10.1007/s10802-012-9630-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto PB, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2004). Trajectories of depressive symptoms among high risk African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 468–477. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Moss HB, & Audrain-McGovern J. (2005). Developmental heterogeneity in adolescent depressive symptoms: associations with smoking behavior. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 200–210. 10.1097/01.psy.0000156929.83810.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallinen M, Rönkä A, Kinnunen U, & Kokko K. (2007). Trajectories of depressive mood in adolescents: Does parental work or parent-adolescent relationship matter? A follow-up study through junior high school in Finland. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31, 181–190. 10.1177/0165025407074631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert KO, Clark SR, Van LK, Collinson JL, & Baune BT (2017). Depressive symptom trajectories in late adolescence and early adulthood: A systematic review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 477–499. 10.1177/0004867417700274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. (1978). Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464. 10.1214/aos/1176344136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333–343. 10.1007/BF02294360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore L, Toumbourou JW, Lewis AJ, & Kremer P. (2017). Review: Longitudinal trajectories of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and their predictors – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23, 107–120. 10.1111/camh.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2001). Adolescent Development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Brown E, Freedenthal S, House L, Ostmann E, & Yu MS (2007). American Indian Youth: Personal, Familial, and Environmental Strengths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 331–346. 10.1007/s10826-006-9089-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Kim HK, & Capaldi DM (2005). The course of depressive symptoms in men from early adolescence to young adulthood: identifying latent trajectories and early predictors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 331–345. 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan L, Misra G, & Marsella AJ (2013). Indigenous Approaches to Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Mental Disorders In Paniagua FA & Yamada A-M (Eds.), Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health (Second Edition) (pp. 69–87). San Diego: Academic Press; 10.1016/B978-0-12-394420-7.00004-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thrane LE, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, & Shelley MC (2004). Comparing three measures of depressive symptoms among American Indian adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research (Online), 11, 20–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & Enders KC (2008). Identifying the Correct Number of Classes in a Growth Mixture Model In Hancock GR & Samuelsen KM (Eds.), Advances in latent variable mixture models. Information Age (pp. 317–314). Greenwich, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger JM, & Nikolas MA (2017). A meta-analytic review of the association between pubertal timing and psychopathology in adolescence: Are there sex differences in risk? Psychological Bulletin, 143, 903–938. 10.1037/bul0000106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci A, & McCauley Ohannessian C. (2018). Self-Competence and Depressive Symptom Trajectories during Adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1089–1109. 10.1007/s10802-017-0340-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hartshorn K, & Walls M. (2014). Indigenous Adolescent Development: Psychological, Social and Historical Contexts (1 edition). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt D, Johnson K, & Chen X. (2006). Mental Disorders among Parents/Caretakers of American Indian Early Adolescents in the Northern Midwest. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 632–640. 10.1007/s00127-006-0070-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Yu M, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, & Walls ML (2008). Diagnostic Prevalence Rates from Early to Mid-Adolescence among Indigenous Adolescents: First Results from a Longitudinal Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 890–900. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama T, & Wickrama KAS (2010). Heterogeneity in Adolescent Depressive Symptom Trajectories: Implications for Young Adults’ Risky Lifestyle. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47, 407–413. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1990). Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Version 1.0. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P-C (2017). The Developmental Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms in Early Adolescence: An Examination of School-Related Factors. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 35, 755–767. 10.1177/0734282916660415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaroslavsky I, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, & Roberts RE (2013). Heterogeneous trajectories of depressive symptoms: Adolescent predictors and adult outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148, 391–399. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]