Summary

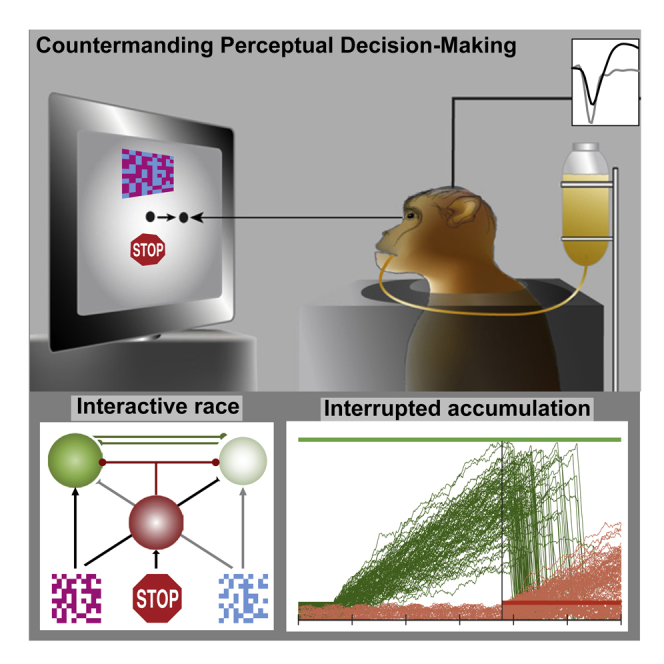

We investigated whether a task requiring concurrent perceptual decision-making and response control can be performed concurrently, whether evidence accumulation and response control are accomplished by the same neurons, and whether perceptual decision-making and countermanding can be unified computationally. Based on neural recordings in a prefrontal area of macaque monkeys, we present behavioral, neural, and computational results demonstrating that perceptual decision-making of varying difficulty can be countermanded efficiently, that single prefrontal neurons instantiate both evidence accumulation and response control, and that an interactive race between stochastic GO evidence accumulators for each alternative and a distinct STOP accumulator fits countermanding choice behavior and replicates neural trajectories. Thus, perceptual decision-making and response control, previously regarded as distinct mechanisms, are actually aspects of a common neuro-computational mechanism supporting flexible behavior.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Neuroscience, Behavioral Neuroscience, Sensory Neuroscience, Cognitive Neuroscience

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Monkeys can perform combined perceptual decision-making and countermanding

-

•

Prefrontal neurons accumulate evidence, but this accumulation can be interrupted

-

•

Interactive race of response accumulators and a stop accumulator explains findings

-

•

Results clarify the circuit logic of brain regions involved in decision-making

Biological Sciences; Neuroscience; Behavioral Neuroscience; Sensory Neuroscience; Cognitive Neuroscience

Introduction

Perceptual decision-making is commonly studied using two-alternative forced-choice tasks in which one of two responses is produced based on a visual discrimination. Performance is explained by sequential sampling of evidence accumulation, which appear to correspond to the dynamics of particular neurons in sensorimotor brain structures (O'Connell et al., 2018, Ratcliff et al., 2016, Schall, 2019). Response control is commonly studied using stop-signal (countermanding) tasks in which a planned response should be withheld if a stop-signal occurs. Performance is explained by race models of the initiation or cancellation of a response, which correspond to the dynamics of particular neurons in sensorimotor structures (Boucher et al., 2007, Logan and Cowan, 1984, Logan et al., 2015, Verbruggen and Logan, 2009). Neither standard model accounts for performance and neurophysiology of the other task, and it is unknown whether neurons instantiate both processes. Therefore we investigated (1) whether perceptual decisions and response control can be performed concurrently, (2) whether they are accomplished by the same neurons, and (3) whether perceptual decision-making and countermanding can be unified computationally.

Results

Countermanding Choice Performance

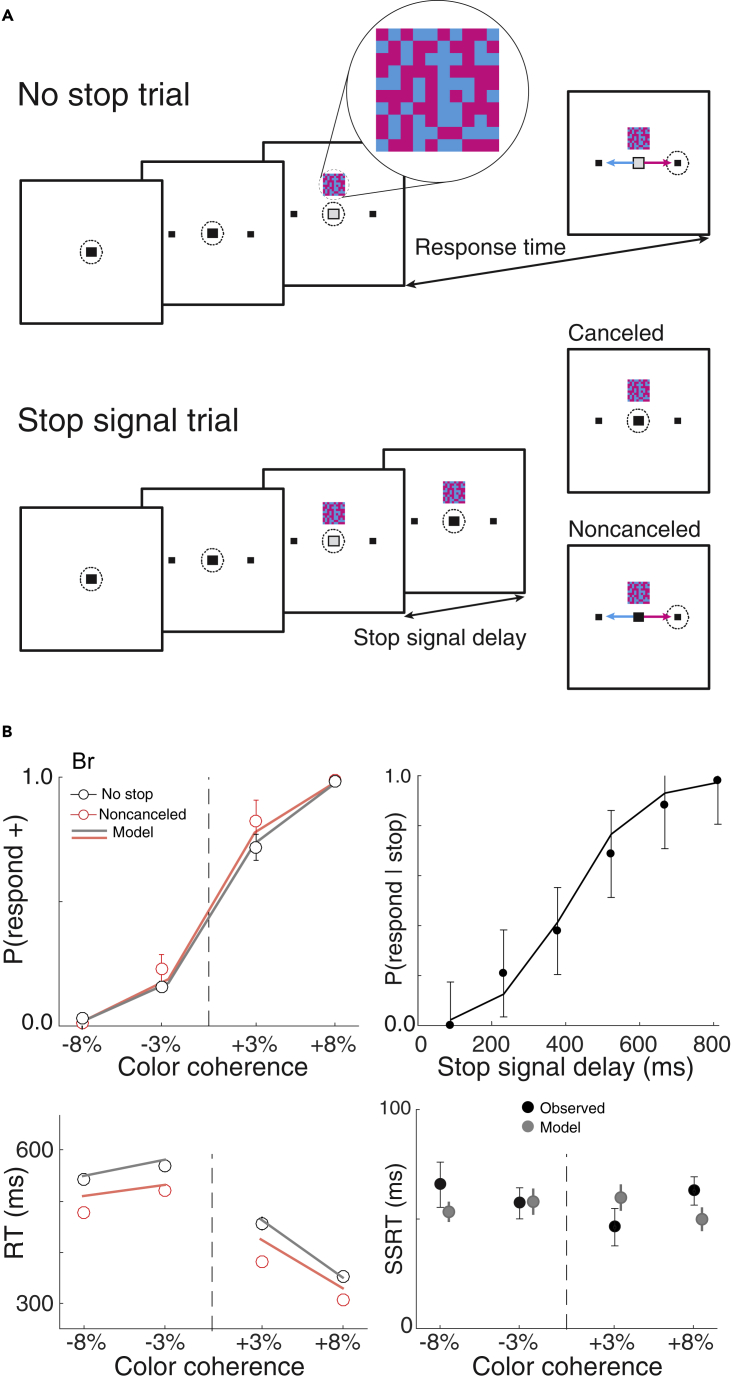

Neural spiking was sampled from two macaque monkeys (Br, Jo) performing a task that combined visual decision-making and saccade countermanding. On each trial, a cyan and magenta checkerboard was presented. The color coherence of the checkerboard was varied to influence the choice direction and discrimination difficulty. Monkeys reported the majority color with a saccade to one of two peripheral targets consistently mapped onto each color (Figure 1A). On a minority of trials (∼30%), a visual stop-signal was presented at the fixation point after a variable stop-signal delay. On no-stop trials, reinforcement was earned for a correct choice. On stop-signal trials, two outcomes were possible. Reinforcement was earned for canceling the choice saccade. No reinforcement was delivered if the saccade was not canceled. Analysis of performance using the Logan and Cowan (1984) race model provides a measure of the duration of the countermanding process, known as stop-signal reaction time (SSRT) (Verbruggen et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Perceptual Decision Countermanding Task

(A) No-stop trials (top panel) began by fixating a central spot. After a variable delay, two targets appeared in the periphery. After another variable delay, a 10 × 10 checkerboard choice stimulus (magnified inset) appeared 3° above the fixation spot, while the fixation spot simultaneously disappeared. The checkerboard was composed of variable fractions of cyan and magenta squares. Fluid reward was delivered if monkeys shifted gaze to the target assigned to the majority color. On a minority of trials (stop-signal trials, bottom panel), the fixation spot reappeared after a variable stop-signal delay. Reward was delivered if monkeys canceled the planned saccade.

(B) Performance of monkey Br during neural recordings. Upper left: Mean ± SEM choice probability as a function of color coherence for no-stop (black) and non-canceled (red) trials. Gray and red lines plot values predicted by best fit model. Upper right: Inhibition function averaged across all sessions. Solid line plots the inhibition function predicted by the best fit model. Lower left: Mean ± SEM of response time (RT) as a function of color coherence for correct choice no-stop (black) and non-canceled (red) trials. Non-canceled RT was systematically shorter than no-stop RT, justifying the application of the Logan and Cowan race model. Gray and red lines plot values predicted by the best fit model. Lower right: Mean ± SEM stop-signal reaction time (SSRT) derived from race model as a function of color coherence (black). SSRT did not vary with decision-making difficulty. Mean ± maximum and minimum SSRT predicted by the best fit model (gray).

Performance data from each monkey manifest classical features of both the perceptual decision-making and the countermanding tasks (Figures 1B and S1, Table S1). Response times and error rate both increased with difficulty across both color coherence and stop-signal delay (Br: RT: F(3,59) = 12.10, ηp2 = 0.38, p < 0.001; error rate: F(3,35) = 759, ηp2 = 0.50, p < 0.001; Jo: RT: F(3,62) = 3.78, ηp2 = 0.15, p = 0.015; error rate: F(3,35) = 363, ηp2 = 0.49, p < 0.001). Discrimination difficulty manipulated by color coherence had no effect on SSRT (Br: F(3,16) = 0.86, ηp2 = 0.14, p = 0.48; Jo: F(3,16) = 0.68, ηp2 = 0.11, p = 0.58). This pattern of results was replicated in performance collected in separate sessions with monkey Br and with a third monkey (X) (Figure S1, Table S1). Replicating previous findings with macaques and humans (Logan et al., 2014, Middlebrooks and Schall, 2014), perceptual decision-making and response inhibition appear to operate concurrently and efficiently.

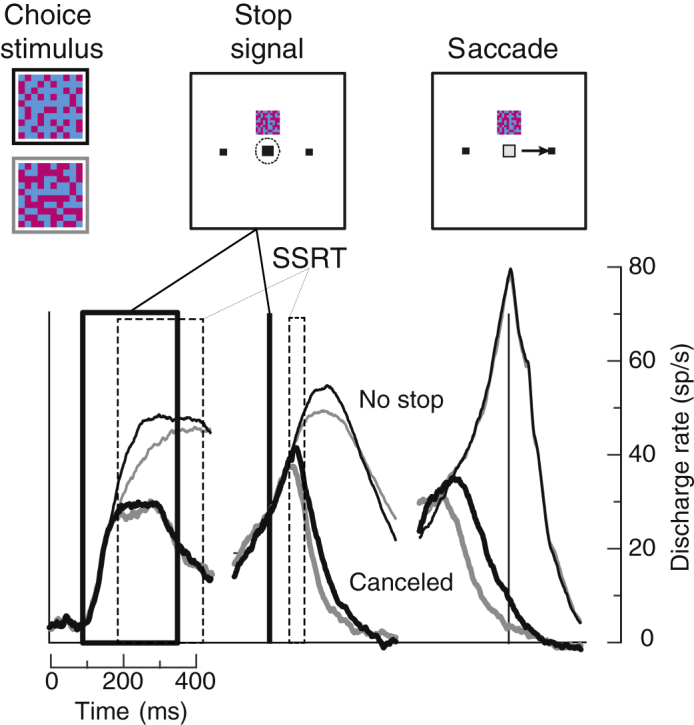

Neural Spiking during Choice Countermanding

Patterns of neural spiking sampled in the frontal eye field (FEF), a prefrontal area at the interface of visual decision-making and saccade production (Schall, 2015), also manifest classical features of both the perceptual decision-making and the countermanding tasks (Figures 2 and S2). This report is based on 1,398 neural spiking samples of which 696 were modulated during the task with 206 exhibiting presaccadic ramping activity. Of these presaccadic units, 52% were modulated with the difficulty of the perceptual choice mirroring the evidence accumulation process accounting for the variation of response time (RT) (Figure 2, Table S2), replicating previous observations (Ding and Gold, 2012).

Figure 2.

Neural Mechanism of Perceptual Decision Countermanding

Average discharge rates of neurons representing the perceptual decision variable and instantiating race model GO process. Discharge rate is plotted as a function of time relative to presentation of the choice stimulus (left), stop-signal (middle), and saccade (right). The thick lines mark times when stop-signal occurred across trials. Dashed lines mark corresponding SSRT across sessions. On trials with no stop-signal (thin), discharge rates accumulated faster with higher (black) relative to lower (gray) color coherence but reached the same trajectory immediately before saccade initiation. On successfully canceled stop-signal trials (thick), accumulating discharge rates were inhibited before SSRT.

As observed before, when saccades were not canceled, modulation of the presaccadic units was indistinguishable from no-stop trials with equivalent RTs (Figure S2). When choice saccades were canceled, 58% presaccadic units modulated before SSRT in a manner sufficient to control saccade initiation, also replicating previous observations (Hanes et al., 1998, Murthy et al., 2009, Paré and Hanes, 2003) (Table S2).

We now report that when choice saccades were canceled, of the 52% presaccadic neurons modulated with perceptual difficulty, 81% also modulated before SSRT (Table S2). This was observed in well-isolated, single units (Figure S2). Presaccadic ramping neurons in FEF have been identified computationally with the GO process of countermanding (Boucher et al., 2007, Logan et al., 2015) and with evidence accumulation for perceptual decision-making (Ding and Gold, 2012, Purcell et al., 2010, Purcell et al., 2012). These results show that evidence accumulation and response inhibition are instantiated concurrently by single neurons in prefrontal cortex.

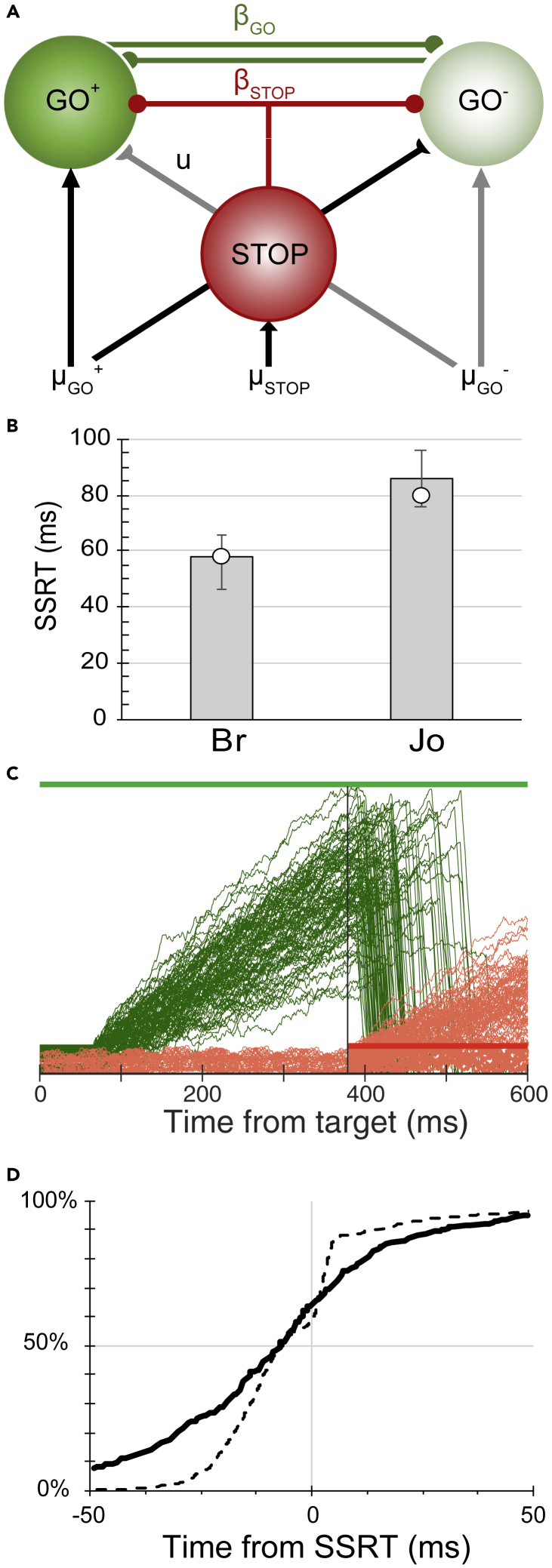

Neuro-computational Model of Choice Countermanding

To determine how neurally plausible choice and stopping models can be unified, we tested an interactive choice race model consisting of two stochastic accumulators for each response alternative (GO+, GO−) plus a STOP accumulator (Figure 3). The two GO units and one STOP unit could accumulate activation and interact in various ways defined by particular parameters. We explored which parameters provided the best fit of the correct and error RT distributions, and the variation of choice accuracy and SSRT across choice difficulty and stop-signal delays. The quality of the fits was evaluated with Bayesian information criteria. This model framework with different types of parameter constraints afforded nested hypothesis testing among several distinct architectures.

Figure 3.

Interactive Race Model of Countermanding Perceptual Decision-Making

(A) Model architecture. Alternative decisions are committed when the accumulated activation of one of the GO units reaches a threshold. The accumulation of each GO unit was driven by the evidence supporting each alternative. This accumulation could be reduced by feedforward inhibition proportional to the evidence supporting the other alternative and by lateral inhibition from the other GO unit. Decisions are canceled if the activation of a STOP unit inhibits the GO units. This inhibition arises after a delay, which preserves the stochastic independence of the race finish times.

(B) Comparison of model SSRT for each monkey (circles) with observed SSRT average (bars) and range of minimum and maximum values across sessions (error bars).

(C) Representative trajectories of GO unit and STOP unit on trials with a stop-signal when the response was successfully canceled.

(D) Observed (solid) and simulated (dashed) cancel times.

We tested three mechanisms of choice nested within the same general model architecture (race (u = 0, βGO = 0), feedforward inhibition (u > 0, βGO = 0), and lateral inhibition (u = 0, βGO > 0) between the GO units) and one mechanism of inhibition from the STOP to the GO units (βSTOP > 0). For each architecture, we also evaluated the quality of the fits for five forms of parameter flexibility (Table S3). (1) To account for asymmetric RT across response alternatives, different baseline values (A0) were allowed for each GO accumulator. (2) To account for variation in RT as a function of color coherence, the GO accumulation rate (μGO) was allowed to vary with coherence level, but the values were constrained to be equal for the two alternatives. (3) To account for both overall RT asymmetries and variation of RT across color coherence, both baseline values and coherence-dependent accumulation were allowed. (4) To account for asymmetric variation of RT as a function of color coherence, the accumulation rate was allowed to be asymmetric across the two alternatives. (5) To account for both overall RT asymmetries and asymmetric variation of RT as a function of color coherence, asymmetric variation of both baseline values and accumulation rates were allowed. Variation of threshold (Aθ_GO) or non-decision time (t0_GO) across conditions did not improve fits to the performance measures. Each architecture accounted well for the combined choosing and stopping performance, with only modest differences in the goodness of fit of the race, feedforward inhibition, and lateral inhibition mechanisms. We regard this as evidence for a robust computational unification of perceptual decision-making and response control because mathematically distinct but functionally similar neural networks can accomplish common functions (Marder et al., 2015).

Performance during neural recordings was fit best by a model with lateral inhibition between the two GO units (u = 0, βGO > 0) and potent inhibition of the GO units by the STOP unit (βSTOP ≫ 0) (Figure 3, Tables 1 and S3). Asymmetric variation in color coherence difficulty was best accounted for by asymmetric variation in GO unit accumulation rates (μGO+ ≠ μGO−). Decision error rates were best accounted for by the combination of variation in relative baseline levels and accumulation rates across the two alternatives. Response inhibition was accounted for by late, potent inhibition of the GO units by the STOP unit. The best-fitting models fit the basic performance measures well on average (Figures 1 and S1) and across RT distributions (Figure S3). The interactive choice race model also fit performance collected in separate sessions in monkey Br and in a third monkey (X) (Figure S1, Table S1).

Table 1.

Parameters of Best-Fit Models for Performance during Neural Recording

| Br Neural |

Jo Neural |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters of Best Fit Model | Lateral Inhibition | Lateral Inhibition | ||

| A0_GO+ | 14.9 | 6.0 | ||

| A0_GO- | 93.4 | 18.1 | ||

| A0_STOP | 12.9 | 9.6 | ||

| Aθ_GO | 150.4 | 39.3 | ||

| Aθ_STOP | 13.7 | 14.6 | ||

| COH | COH | |||

| μGo+ | −8% | 0.07 | −10% | 0.09 |

| −3% | 0.11 | −5% | 0.16 | |

| 3% | 0.24 | 5% | 0.19 | |

| 8% | 0.37 | 10% | 0.22 | |

| μGo- | −8% | 0.31 | −10% | 0.40 |

| −3% | 0.28 | −5% | 0.33 | |

| 3% | 0.24 | 5% | 0.24 | |

| 8% | 0.16 | 10% | 0.12 | |

| μSTOP | 0.14 | 0.13 | ||

| U | −7.80 × 10−16 | −0.058 | ||

| βSTOP | −0.477 | −0.410 | ||

| t0_GO | 66 | 120 | ||

| t0_STOP | 9 | 13 | ||

Activation of units began at a baseline level on each trial drawn from a uniform distribution [0:A0], which could have different values for the GO+, GO−, and STOP units and completed when it reached the respective thresholds (Aθ_GO, Aθ_STOP). The activation of each GO unit increased with input strength, which varied with color coherence and response direction (μ(COHi, DIRj)) and decreased according to lateral inhibition (u) and STOP unit inhibition (βSTOP). The activation of the STOP unit (aSTOP) increased with input strength (μSTOP). Activation of each unit began after a stimulus encoding non-decision time (t0_GO, t0_STOP). Choice countermanding performance was fit best with lateral inhibition between the GO units, and late potent inhibition of the GO unit, by the STOP unit.

Our approach to testing computational models requires more than fits to performance. The model is supposed to explain what neurons are doing through time. Therefore, we compared the observed times when presaccadic neural activity was interrupted on canceled trials with the times measured in simulated trajectories of GO units with best-fit parameters. As observed in the simpler interactive race model (Boucher et al., 2007, Logan et al., 2015), we found that the STOP unit interrupted the accumulation of the GO units at times corresponding to those measured from the sampled neurons (Figure 3). Hence, these results demonstrate the graceful and robust computational unification of the two primary models of decision-making and response control.

Discussion

Based on the following considerations, we believe the current results can be interpreted more generally. First, the performance measured during neural recordings corresponded to performance measured in other monkeys and four human participants (Middlebrooks and Schall, 2014). Second, the patterns of neural modulation observed corresponded to patterns observed previously in monkeys performing tasks that require only saccade countermanding (Hanes et al., 1998, Paré and Hanes, 2003) or tasks that require only perceptual decision-making (Ding and Gold, 2012, Ratcliff et al., 2003, Roitman and Shadlen, 2002). Therefore, the observation that neurons representing the decision variable for a perceptual decision can be countermanded may be regarded as robust. Third, the quality of the fits achieved by this countermanding decision model was comparable with those achieved by previous fits to perceptual decision or to countermanding performance alone (Boucher et al., 2007, Lo et al., 2009, Logan et al., 2015, Mazurek et al., 2003, Purcell et al., 2010, Purcell et al., 2012, Wei and Wang, 2016). Thus, elaborating previous theoretical work (Logan et al., 2014), the interactive race choice countermanding model unifies previously distinct model frameworks.

We sampled some neurons that statistically failed to signal the perceptual decisions. We believe that this is not a consequential observation. Most of these neurons had weak responses to the choice targets, so we surmise that the weak modulation was simply due to a lack of overlap of the most sensitive region of the neuron's response field and the placement of the choice targets. We also sampled neurons that did not modulate before SSRT or at all when choice saccades were canceled. Such diversity in FEF has been found before (Hanes et al., 1998). Further research can elucidate the circuitry of these diverse neurons.

The major general conclusion we draw is that the existence of neurons contributing to both functions concurrently suggests a unity of two cognitive operations that have been regarded as distinct in the visual neuroscience research community. Is this outcome surprising? Was it a foregone conclusion that response selection and the countermanding process interact? This view implies an identification of “perceptual decision-making” with “response selection”; however, other research has highlighted distinctions (e.g., Gold and Shadlen, 2003). Hence, the alternative outcome is that neurons signal the perceptual decision variable but are entirely unaffected by whether or not the movement is canceled. Such a result is likely to be the case in the lateral intraparietal area (LIP) where neurons do not modulate before SSRT (Paré and Dorris, 2011).

Is it reasonable to think that perceptual decision-making and response control are mutually exclusive and would not be performed concurrently? Perhaps the lateralized perceptual decision-making used in this task requires allocation of spatial attention, which corresponds to saccade preparation (Awh et al., 2006). Although spatial attention is certainly necessary for this task, the activity of presaccadic movement neurons in FEF has been dissociated from spatial attention in three different ways. First, visual attention shifts without saccade preparation (Juan et al., 2004). Second, neurons in FEF that mediate visual attention are not connected to saccade motor circuits (Pouget et al., 2009). Third, when attention allocation is signaled with limb movements, the visually responsive neurons in FEF modulate as usual, whereas the movement neurons are suppressed (Thompson et al., 2005). These observations contradict the hypothesis that the activity of FEF movement neurons can be identified with both motor planning and shifting spatial attention.

Conditions in which STOP and GO processes interact strongly have been described (Verbruggen and Logan, 2015). We would also emphasize that the concepts of independence and interaction can have different manifestations at different levels of description. The stochastic independence of GO and STOP processes is central to the Logan and Cowan (1984) race model. However, the discovery that neurons in motor circuits are strongly modulated before SSRT demonstrates clearly that the neural processes instantiating the GO and STOP processes must interact (Hanes et al., 1998, Paré and Hanes, 2003). The interactive race models demonstrate how the appearance of independence and the fact of interaction can be reconciled computationally and mechanistically (Boucher et al., 2007, Logan et al., 2015).

This unification provides a fresh insight into the relationship of deciding and stopping. The STOP unit inhibition parameter was considerably stronger than the GO unit lateral inhibition. Of course, in the race architecture the STOP unit inhibition was infinitely greater than the interaction between GO units. Across all model fits, the STOP unit inhibition averaged 13 orders of magnitude greater than lateral inhibition between GO units and 5 orders of magnitude greater than forward inhibition on GO units (Table S3). Moreover, as found earlier (Boucher et al., 2007, Logan et al., 2015), the action of the STOP unit was necessarily delayed to preserve the independence of the finishing times of the racing GO and STOP processes. These model parameters entail that although response inhibition can be conceived as an alternative decision in the model architecture, it functions with dynamics different from the processes producing overt responses. In other words, interrupting a choice is different from executing one among alternative choices.

Our findings confirm a specific linkage in prefrontal cortex between response preparation and perceptual decision-making. This contradicts an earlier conclusion that frontal cortex in rodents does not contribute to evidence accumulation (Hanks et al., 2015), but replicates multiple, previous, independent observations (Ding and Gold, 2012, Purcell et al., 2010, Purcell et al., 2012). The existence of neurons in prefrontal cortex instantiating evidence accumulation also provides an explanation for the persistence of perceptual decision-making when posterior cortical areas are inactivated (Katz et al., 2016) and the ability of monkeys to perform the task before posterior parietal neurons acquire the accumulation process (Law and Gold, 2008). Taken together, these results suggest that the evidence accumulation signal reported in parietal cortex is derived from more primary processes occurring in the frontal lobe and perhaps subcortically. This hypothesis would be verified if inactivation of FEF disrupted performance of perceptual decision-making and countermanding with saccadic eye movements.

Thus, innovative performance, neural signaling, and computational modeling results demonstrate that perceptual decisions and response inhibition are not separate processes but instead just different descriptions of a single process traditionally tested in different modes of operation. Our results elaborate further constraints on the circuit logic of brain regions involved in decision-making.

Limitations of the Study

The conclusions are constrained by the following limitations. First, no inactivation was done to determine whether FEF is necessary for performance of this task. However, lesion (Dias and Segraves, 1999) and inactivation (Wardak et al., 2006) studies have demonstrated that FEF is necessary for saccades produced in more complex conditions including perceptual decision-making during visual search. Also, interpretation of inactivation findings is always limited by questions about the actual extent and efficacy of the inactivation. Second, neural discharges were not sampled in other brain regions known to contribute to performance of this task. We do not know, for example, how neurons in posterior parietal cortex contribute to performance of this combined task given the absence of modulation when saccades are countermanded (Paré and Dorris, 2011). Also, we do not know how the choice stimulus or the stop-signal is encoded from visual processing through task rule, but evidence indicates that this likely involves other prefrontal areas (Xu et al., 2017). Ultimately, this specific task and general approach offers an effective means of assessing the contributions of multiple nodes in the distributed network that supports perceptual decision-making and response control.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by F32-EY023526, R01-MH55806, R01-EY021833, P30-EY008126, U54-HD083211, and by the NIH grant is S10-OD023680 supporting the Vanderbilt University Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education, and by Robin and Richard Patton through the E. Bronson Ingram Chair in Neuroscience. We thank J. Elsey M. Feurtado, M. Maddox, S. Motorny, J. Parker, M. Schall, and L. Toy for animal care and other technical assistance. Request for materials should be addressed to J.D.S. (e-mail: jeffrey.d.schall@vanderbilt.edu).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G.M., B.B.Z., G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.; Methodology, P.G.M., B.B.Z., G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.; Software, P.G.M., B.B.Z.; Validation, G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.; Formal Analysis, P.G.M., B.B.Z., and J.D.S.; Investigation, P.G.M., J.D.S.; Writing – Original Draft, P.G.M. and J.D.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, P.G.M., B.B.Z., G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.; Visualization, P.G.M. and J.D.S.; Supervision, G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.; Funding Acquisition, G.D.L., T.J.P., and J.D.S.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.100777.

Data and Code Availability

All datasets and custom analysis programs will be made available upon request to the Lead Contact, Jeffrey D Schall (jeffrey.d.schall@vanderbilt.edu).

Supplemental Information

Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and parameters of all models fit to all four datasets in separate tabs of the Excel sheet. Parameters with lowest BIC are indicated by bold font. Parameters with second lowest BIC are indicated by italics font. For completeness, we considered three mechanisms of choice (race, feedforward inhibition, and lateral inhibition between GO units) and one mechanism of inhibition (inhibition from STOP to GO units). For each architecture we explored fits for five combinations of parameters. (1) To account for lateralized RT asymmetries, A0+ ≠ A0-. (2) To allow for variation of evidence across color coherence, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj), but μGO+(COHi) = μGO−(COHi). (3) To account for both RT asymmetries and variation of evidence across color coherence, A0+ ≠ A0-, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj), and μGO+(COHi) = μGO−(COHi). (4) To allow for asymmetric variation of evidence across color coherence, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj) and μGO+(COHi) ≠ μGO−(COHi). (5) To account for both RT asymmetries and allow for asymmetric variation of evidence across color coherence, A0+ ≠ A0-, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj) and μGO+(COHi) ≠ μGO−(COHi). Parameter sets 1 and 2 were explored to evaluate fits of implausible models, whereas parameter sets 3, 4, and 5 were expected to account better for the variation of performance. Variation of threshold and/or non-decision time did not improve fits to the behavioral performance. Each architecture accounted for the combination of choosing and stopping performance, with only modest differences in the goodness of fit of race, feedforward inhibition, and lateral inhibition decision mechanisms.

References

- Awh E., Armstrong K.M., Moore T. Visual and oculomotor selection: links, causes and implications for spatial attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006;10:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher L., Palmeri T.J., Logan G.D., Schall J.D. Inhibitory control in mind and brain: an interactive race model of countermanding saccades. Psychol. Rev. 2007;114:376–397. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias E.C., Segraves M.A. Muscimol-induced inactivation of monkey frontal eye field: effects on visually and memory-guided saccades. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2191–2214. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Gold J. Neural correlates of perceptual decision making before, during, and after decision commitment in monkey frontal eye field. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:1052–1067. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold J.I., Shadlen M.N. The influence of behavioral context on the representation of a perceptual decision in developing oculomotor commands. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:632–651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00632.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes D.P., Patterson W.F., Schall J.D. Role of frontal eye fields in countermanding saccades: visual, movement, and fixation activity. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:817–834. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks T.D., Kopec C.D., Brunton B.W., Duan C.A., Erlich J.C., Brody C.D. Distinct relationships of parietal and prefrontal cortices to evidence accumulation. Nature. 2015;520:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan C., H., Shorter-Jacobi S., M., Schall J., D. Dissociation of spatial attention and saccade preparation. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U S A. 2004;101:15541–15544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403507101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L.N., Yates J.L., Pillow J.W., Huk A.C. Dissociated functional significance of decision-related activity in the primate dorsal stream. Nature. 2016;535:285–288. doi: 10.1038/nature18617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law C.-T., Gold J.I. Neural correlates of perceptual learning in a sensory-motor, but not a sensory, cortical area. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:505–513. doi: 10.1038/nn2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C.C., Boucher L., Paré M., Schall J.D., Wang X.J. Proactive inhibitory control and attractor dynamics in countermanding action: a spiking neural circuit model. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9059–9071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6164-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan G.D., Cowan W.B. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: a theory of an act of control. Psychol. Rev. 1984;91:295–327. doi: 10.1037/a0035230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan G.D., Van Zandt T., Verbruggen F., Wagenmakers E.J. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: general and special theories of an act of control. Psychol. Rev. 2014;121:66–95. doi: 10.1037/a0035230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan G.D., Yamaguchi M., Schall J.D., Palmeri T.J. Inhibitory control in mind and brain 2.0: blocked-input models of saccadic countermanding. Psychol. Rev. 2015;122:115–147. doi: 10.1037/a0038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E., Goeritz M.L., Otopalik A.G. Robust circuit rhythms in small circuits arise from variable circuit components and mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015;31:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek M.E., Roitman J.D., Ditterich J., Shadlen M.N. A role for neural integrators in perceptual decision making. Cereb. Cortex. 2003;13:1257–1269. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks P.G., Schall J.D. Response inhibition during perceptual decision making in humans and macaques. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2014;76:353–366. doi: 10.3758/s13414-013-0599-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy A., Ray S., Shorter S.M., Schall J.D., Thompson K.G. Neural control of visual search by frontal eye field: effects of unexpected target displacement on visual selection and saccade preparation. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2485–2506. doi: 10.1152/jn.90824.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell R.G., Shadlen M.N., Wong-Lin K., Kelly S.P. Bridging neural and computational viewpoints on perceptual decision-making. Trends Neurosci. 2018;41:838–852. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré M., Dorris M. The role of posterior parietal cortex in the regulation of saccadic eye movements. In: Liversedge S., Gilchrist I., Everling S., editors. Oxford Handbook of Eye Movements. OUP Oxford; 2011. pp. 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Paré M., Hanes D.P. Controlled movement processing: superior colliculus activity associated with countermanded saccades. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:6480–6489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06480.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget P., Stepniewska I., Crowder E., A., Leslie M., W., Emeric E., E., Nelson M., J., Schall J., D. Visual and motor connectivity and the distribution of calcium-binding proteins in macaque frontal eye field: implications for saccade target selection. Front Neuroanat. 2009;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell B.A., Heitz R.P., Cohen J.Y., Schall J.D., Logan G.D., Palmeri T.J. Neurally constrained modeling of perceptual decision making. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:1113–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0020311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell B.A., Schall J.D., Logan G.D., Palmeri T.J. From salience to saccades: multiple-alternative gated stochastic accumulator model of visual search. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:3433–3446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4622-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R., Cherian A., Segraves M.A. A comparison of macaque behavior and superior colliculus neuronal activity to predictions from models of two choice decisions. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1392–1407. doi: 10.1152/jn.01049.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R., Smith P.L., Brown S.D., McKoon G. Diffusion decision model: current issues and history. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016;20:260–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman J.D., Shadlen M.N. Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area during a combined visual discrimination reaction time task. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:9475–9489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09475.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall J.D. Visuomotor functions in the frontal lobe. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2015;1:469–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-082114-035317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schall J.D. Accumulators, neurons, and response time. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42:848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K., G., Biscoe K., L., Sato T., R. Neuronal basis of covert spatial attention in the frontal eye field. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9479–9487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0741-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F., Logan G.D. Models of response inhibition in the stop-signal and stop-change paradigms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009;33:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F., Logan G.D. Evidence for capacity sharing when stopping. Cognition. 2015;142:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F., Aron A.R., Band G.P., Beste C., Bissett P.G., Brockett A.T., Brown J.W., Chamberlain S.R., Chambers C.D., Colonius H. A consensus guide to capturing the ability to inhibit actions and impulsive behaviors in the stop-signal task. Elife. 2019 doi: 10.7554/eLife.46323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardak C., Ibos G., Duhamel J.R., Olivier E. Contribution of the monkey frontal eye field to covert visual attention. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4228–4235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3336-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Wang X.J. Inhibitory control in the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical loop: complex regulation and interplay with memory and decision processes. Neuron. 2016;92:1093–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K.Z., Anderson B.A., Emeric E.E., Sali A.W., Stuphorn V., Yantis S., Courtney S.M. Neural basis of cognitive control over movement inhibition: human fMRI and primate electrophysiology evidence. Neuron. 2017;96:1447–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and parameters of all models fit to all four datasets in separate tabs of the Excel sheet. Parameters with lowest BIC are indicated by bold font. Parameters with second lowest BIC are indicated by italics font. For completeness, we considered three mechanisms of choice (race, feedforward inhibition, and lateral inhibition between GO units) and one mechanism of inhibition (inhibition from STOP to GO units). For each architecture we explored fits for five combinations of parameters. (1) To account for lateralized RT asymmetries, A0+ ≠ A0-. (2) To allow for variation of evidence across color coherence, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj), but μGO+(COHi) = μGO−(COHi). (3) To account for both RT asymmetries and variation of evidence across color coherence, A0+ ≠ A0-, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj), and μGO+(COHi) = μGO−(COHi). (4) To allow for asymmetric variation of evidence across color coherence, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj) and μGO+(COHi) ≠ μGO−(COHi). (5) To account for both RT asymmetries and allow for asymmetric variation of evidence across color coherence, A0+ ≠ A0-, μGO(COHi) ≠ μGO (COHj) and μGO+(COHi) ≠ μGO−(COHi). Parameter sets 1 and 2 were explored to evaluate fits of implausible models, whereas parameter sets 3, 4, and 5 were expected to account better for the variation of performance. Variation of threshold and/or non-decision time did not improve fits to the behavioral performance. Each architecture accounted for the combination of choosing and stopping performance, with only modest differences in the goodness of fit of race, feedforward inhibition, and lateral inhibition decision mechanisms.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets and custom analysis programs will be made available upon request to the Lead Contact, Jeffrey D Schall (jeffrey.d.schall@vanderbilt.edu).