Abstract

Objectives

Medication error is the most common type of medical error, and intravenous medicines are at a higher risk as they are complex to prepare and administer. The WHO advocates a 50% reduction of harmful medication errors by 2022, but there is a lack of data in the UK that accurately estimates the true rate of intravenous medication errors. This study aimed to estimate the number of intravenous medication errors per 1000 administrations in the UK National Health Service and their associated economic costs. The rate of errors in prescribing, preparation and administration, and rate of different types of errors were also extracted.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane central register of clinical trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database and the Health Technology Appraisals Database were searched from inception to July 2017. Epidemiological studies to determine the incidence of intravenous medication errors set wholly or in part in the UK were included. 228 studies were identified, and after screening, eight papers were included, presenting 2576 infusions. Data were reviewed and extracted by a team of five reviewers with discrepancies in data extraction agreed by consensus.

Results

Five of eight studies used a comparable denominator, and these data were pooled to determine a weighted mean incidence of 101 intravenous medication errors per 1000 administrations (95% CI 84 to 121). Three studies presented prevalence data but these were based on spontaneous reports only; therefore it did not support a true estimate. 32.1% (95% CI 30.6% to 33.7%) of intravenous medication errors were administration errors and ‘wrong rate’ errors accounted for 57.9% (95% CI 54.7% to 61.1%) of these.

Conclusion

Intravenous medication errors in the UK are common, with half these of errors related to medication administration. National strategies are aimed at mitigating errors in prescribing and preparation. It is now time to focus on reducing administration error, particularly wrong rate errors.

Keywords: medication errors, intravenous infusions, public hospitals, information technology, clinical pharmacy

Introduction

Medication errors are the most common form of medical error and have been the subject of much previous research. It is estimated that medication errors have contributed to 12 000 deaths per year in the National Health Service (NHS) and that the wider problem of medication errors may contribute to an additional £0.75 billion–£1.5 billion in additional healthcare expenditure.1 The burden of mortality and morbidity associated with medication error is such that the WHO has committed to a global programme of work to reduce harm to patients caused by medication errors by 50% by 2022.2

Intravenous medication is associated with the greatest risk of medication error.3 They can be technically complex to prepare and administer,4 and when they are administered in error, the negative effects of these preparations are more difficult to mitigate due to the immediate and complete absorption and distribution into the blood stream. In 2017, the ECRI Institute declared intravenous medication errors to be the number one threat to patient safety in the USA; however, this review focused on the use of physical fail-safes to prevent intravenous free flow events, which technological interventions may lead practitioners to overlook.5 The Institute of Safe Medical Practice’s ‘high alert drugs’ list is dominated by injectable medications.6 As medicine becomes more complex, intravenous therapy is a field that continues to grow.

Background

The risks of medication error with intravenous medicines are well documented. Errors occur at any and all stages of prescribing, preparation and administration of intravenous medicines. Errors in preparation and administration have included wrong drug selection, using the incorrect diluent for diluting and wrong rate of infusion. A number of interventions have been designed to mitigate these errors,7–9 double checking of intravenous drugs,10 preprogrammed infusion pumps that offer a check of rate and dose (‘smart’ pumps)11 and provision of ready to administer drug formulations.12 While some interventions have proven beneficial, baseline error data used to assess their efficacy is often of poor quality. As a result, the merit of many interventions has been questioned. Furthermore, due to their use in a single setting, the findings of any evaluations have lacked generalisability. Heterogeneity of study design and outcome measures in the literature obscure the true nature and size of the problem. Additionally, the practice encompassing intravenous therapy and costs of healthcare-associated morbidity are different between health economies and provider systems such that it may not be appropriate to extrapolate incidence and/or prevalence data from one geographical healthcare setting to another. To date, for numerous reasons, the incidence of intravenous medication errors in the UK is unknown, as data in previous reviews have been synthesised in the context of highly focused and specific questions, or without acknowledgement of geographical/economic differences. Thus, before the efficacy of further interventions aimed at reducing administration error rates in the UK can be evaluated, it is necessary to understand the incidence of intravenous medication errors in this country.

With these facts in mind, we set out to explore the incidence and prevalence of intravenous medication administration errors in the UK healthcare system. Our aim was to systematically review previous studies of the incidence of intravenous medication errors in the UK healthcare system and attempted to appraise the potential costs associated with harm from these errors.

Methods

This review was conducted in line with the statement on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.13

Search strategy

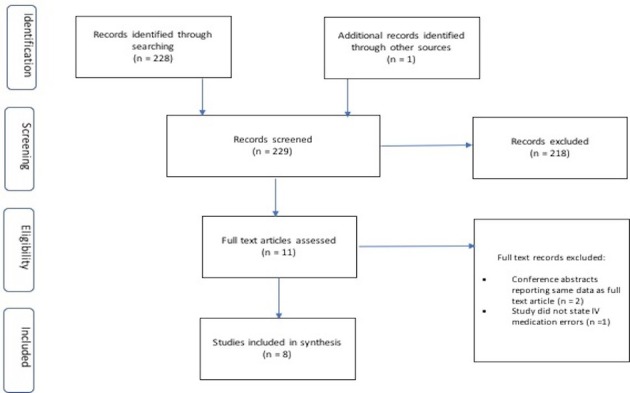

The electronic repositories of six databases were searched: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane central register of clinical trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, NHS Economic Evaluation Database and the Health Technology Appraisals Database. This search was conducted in each database from inception up to July 2017. The search strategy was developed by a health economist (MC), and an abbreviated search strategy is available as an online supplementary file. Grey literature was also searched, including publicly available reports from UK safety agencies (eg, National Reporting and Learning Services (NRLS)) and major safety conferences (eg, National Association for Medical Device Training for Healthcare Professionals (NAMDET)). The citation lists of included papers were also hand searched for additional publications that may not have been revealed by the literature search. This review protocol was not registered with any systematic review registry. The results of the search strategy are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of literature screening. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

ejhpharm-2018-001624supp001.pdf (99.2KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review included studies published in English only. Systematic and narrative reviews and case reports were excluded. Conference abstracts were included where they were unique. Where a later published paper was identified relating to a conference abstract, the abstract was then excluded from the synthesis. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by the lead author (AS) against the following inclusion criteria:

The study was set (at least in part) in the UK.

The study reported any data pertaining to the rate of intravenous errors, presented either as an incidence of prevalence.

Additionally, studies were also identified if they presented an economic analysis of the costs of intravenous medication errors in the UK. All suitable studies that contained epidemiological data relating to errors associated with intravenous medicines were included, including descriptive, observational, before–after studies and randomised controlled trials.

Data extraction and synthesis

The full text of all included papers was then reviewed independently by members of the wider review team (MR, EW, JC, AS and TS), and the evidence was extracted using a purpose-developed proforma. The proforma was piloted to ensure consistent data extraction by both the same and different reviewers using the test retest method. Data extraction was completed by two reviewers, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. Where results were unclear, study data sets were requested from authors for the review team to extract the data themselves. In this situation, the data set was assessed, and errors were categorised as either intravenous or non-intravenous. Non-intravenous reports included pump failures, blood products and parenteral nutrition, oral medication, pump failures with no medication information and reports relating to adverse drug reactions. All other intravenous-related reports were included in the data extraction as per the protocol. This was required for a single study (Thomas et al).

Data for a range of outcomes were extracted. The primary outcome of interest was the overall incidence of intravenous medication errors (per 1000 administrations). Estimates for the overall incidence used the total number of observed infusions as the denominator and were then multiplied up to 1000 administrations to support comparison. Weighted means for administration error rates and 95% CIs of the incidence of errors for these pooled estimates were then calculated. The prevalence of intravenous medication errors (per 1000 patient bed days (pbd)) was extracted where possible.

The incidence of intravenous medication errors was further analysed by stage of the medication process (prescribing, preparation and administration). Subsequently, administration errors were further analysed based on the type of error reported (wrong dose, wrong time, wrong rate, wrong drug, wrong diluent, wrong pump setting and dose omission.) Data for these outcomes were extracted from studies regardless of study design. Rates were calculated using the observed number of errors as the denominator.

Results

In total, eight papers were included in this review of the incidence of intravenous medication errors in the UK.14–21 None involved an economic analysis. The characteristics of these studies are summarised in table 1. Six studies were reported in England, one in Scotland, one in Northern Ireland and none in Wales. All studies were conducted in hospitals: two in general hospitals, five in a specialist hospital setting and one study did not state its setting clearly. Five studies were in mixed ward environments, one that focused specifically in critical care units and two studies did not report their study field. Four studies specifically studied the incidence of medication errors in children and young people’s health services with one limited to adult care contexts. Three studies did not specify the population being investigated. All studies were observational in design with five prospective and three retrospective. All retrospective studies used spontaneous error reports as their outcome of interest, while prospective studies used disguised observation.

Table 1.

Included papers and their characteristics; options available as follows:

| Author | Year | Country | Setting* | Ward type† | Population ‡ | Study design | Definition of error | Detection method |

| Cousins et al 14 | 2005 | England | Hospital – general | Mixed | Not stated | Prospective observational | Definition from Taxis (2003). | Disguised observation |

| Ghaleb et al 15 | 2010 | England | Hospital – specialist | Mixed | Paediatrics | Prospective observational | Ghaleb et al 22 | Disguised observation |

| Narula et al 16 | 2011 | England | Hospital – specialist | Mixed | Paediatrics | Retrospective observational | National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention23 | Spontaneous reporting |

| O’Hare et al 17 | 1995 | Northern Ireland | Hospital – specialist | Not stated | Paediatrics | Prospective observational | United States Pharmacopoeia (USP)33 | Disguised observation |

| Ross et al 18 | 2000 | Scotland | Hospital – specialist | Mixed | Paediatrics | Retrospective observational | Local definition | Spontaneous reporting |

| Taxis and Barber19 | 2003 | England | Hospital – general | Mixed | Not stated | Prospective observational | Local definition | Disguised observation |

| Thomas and Taylor20 | 2014 | England | Not stated | Critical care units | Adults | Retrospective observational | Local definition34 | Spontaneous reporting |

| Wirtz et al 21 | 2003 | England | Hospital – specialist | Not stated | Not stated | Prospective observational | Definition from Taxis (2003).19 | Disguised observation |

*Hospital (general); hospital (specialist); ambulatory care unit; home; not stated.

†Medical; surgical; critical care unit; operating theatre; emergency department; mixed; not stated.

‡Adults; paediatrics; neonates; not stated.

Defining errors and severity

Four of the eight studies used a single definition of an intravenous medication error derived from Taxis and Barber.19 This definition included all deviations from a doctor’s prescription, the hospital intravenous drugs policy and/or the manufacturer’s/technical instructions. No study differentiated between the policy deviated from; therefore, it was possible that multiple deviations were involved in a single error. Other studies used other definitions with different criteria. In total, an error was defined in five different ways across the eligible studies. Only one study used a definition based on clinical importance (Ghaleb et al) that had been developed in a previous study.22 Another study used a definition derived from the National Coordinating Committee Medication Error Reduction Programme (NCC MERP)23 that was then used to support severity classification (Narula et al). This was the only study that evaluated harm associated with errors, all being in the ‘No harm’ category.

The incidence and prevalence of intravenous medication errors

Five studies reported error rates (in per cent) obtained through disguised observation, with a denominator of observed administrations. This enabled some limited manipulation and generalisation of the data (table 2). The crude observed incidence per 1000 administrations across all studies was 265 (range 55–940; 95% CI 249 to 283), and when adjusted to the weighted mean, the incidence of errors was 101/1000 administrations (range 38–643; 95% CI 84 to 121). Three studies reported longitudinal data relating to prevalence of errors in different populations. These are reported in table 3. Together these studies present 854 errors over 600 000 pbd, equating to 1.4 errors per 1000 pbd. However, further estimates are not supported by the data as the studies were so different: Ross et al is 20-year-old data and Narula et al focused on a highly centralised and controlled therapy (parenteral nutrition). Thomas et al reported medication related incidents between 2009 and 2012 in 12 critical care units. Six hundred and ninety-nine reported intravenous medication incidents over 246 552 pbd were identified, yielding an estimated prevalence of intravenous medication errors of 2.84/1000 pbd. Further reliable data extraction from this data set was not possible.

Table 2.

Rate of errors extracted from studies

| Author | Denominator | N | All infusions >1 error (%) | Adjusted to/1000 infusions | Weighted mean/1000 administrations |

| Cousins | Observed infusions | 273 | 185 (67.8) | 678 | 463 |

| Ghaleb* | Observed medication preparation and administration | 1554 | 85 (5.5) | 55 | 38 |

| O’Hare | Observed infusions | 179 | 168 (94) | 940 | 643 |

| Taxis | Observed infusions | 430 | 212 (49.3) | 493 | 337 |

| Wirtz | Observed infusions | 140 | 34 (24.3) | 243 | 166 |

| Total | 2576 | 684 | Mean errors=265 (95% CI 249 to 288) | Weighted mean errors=101 (95% CI 84 to 121) | |

*Data reported all types of error but certain intravenous error types were extractable and are presented.

Table 3.

Prevalence of errors extracted from studies

| Author | Setting | Denominator | N | Intravenous infusion errors | Adjusted to /1000 patient bed days |

| Ross | Tertiary children’s hospital | Patient bed days | 335 835 | 109 | 0.32 |

| Narula | Tertiary children’s hospital | Patient bed days | 18 588 | 46 | 2.47 |

| Thomas | Critical care units (n=12) | Patient bed days | 246 552 | 699 | 2.84 |

| Total | 600 975 | 854 | 1.42 | ||

Incidence of errors in different stages of the medication process

This is summarised in table 4. The majority of intravenous medication errors identified occurred during the administration phase with a mean rate of 32.1% of errors occurring at this phase (range 5.5%–91.4%) compared with 8.65% of errors occurring during preparation (range 1%–31%). The only studies that presented data for prescribing errors were those using spontaneous reporting methods. Thus, although the incidence of prescribing errors appear to be very low (141/3433; 0.05%) within the studies that reported prescribing error rates, the rates were quite high – 21.4% to 30% of incident reports.

Table 4.

Rates of error at different stages of the intravenous administration process (% expressed as proportion of errors)

| Author | Number of included infusions | Prescribing (%) | Preparation (%) | Administration (%) |

| Cousins | 273 | 3 (1) | 182 (66.7) | |

| Ghaleb* | 1554 | 85 (5.5) | ||

| Narula | 46 | 14 (30.4) | 18 (39.1) | 14 (30.4) |

| O’Hare | 291 | 25 (8.6) | 266 (91.4) | |

| Taxis | 430 | 62 (14.4) | 155 (36) | |

| Thomas | 699 | 147 (21.1) | 172 (24.6) | 385 (55.1) |

| Wirtz | 140 | 17/77 (22) | 17/63 (26.9) | |

| Total | 3433 | 161 (0.05) | 297 (8.65) | 1104 (32.1) |

Spaces left blank indicate no reported data pertaining to intravenous medicines.

*Data reported all types of error but certain IV error types were extractable and are presented.

Errors and where they occur in the administration process

It was possible to identify further data on the types of administration errors in seven papers (table 5). The majority of errors detected during intravenous medication administration were wrong rate errors. The mean incidence of wrong rate administration errors was 57.9% (range 8.8%–100%; 95% CI 54.7% to 61.1%). The next most common error type associated with intravenous administration errors was wrong time administration with a mean rate of 20.4% (range 26.4%–83.3%; 95% CI 18% to 23.2%); however, this was only identified in two studies. Remaining errors types (wrong dose, wrong diluent, wrong volume, wrong pump setting and dose omission) contributed less than 20% of remaining error types.

Table 5.

Administration errors by type (columns may not equate due to infusions with >1 error type)

| Author | Number of errors | Wrong drug N (%) |

Wrong dose N (%) |

Wrong rate N (%) |

Wrong diluent N (%) |

Wrong volume N (%) |

Wrong time N (%) |

Wrong pump setting N (%) | Dose omission N (%) |

| Cousins | 185 | 1 (0.5) | 132 (71.4) | 2 (1.1) | 49 (26.4) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ghaleb | 85 | 85 (100) | |||||||

| Narula P | 46 | 7 (15.2) | |||||||

| O’Hare | 168 | 114 (67.9) | 1 (0.6) | 24 (14.3) | 140 (83.3) | 2 (1.2) | |||

| Ross | 195 | 32 (16.4) | |||||||

| Taxis | 212 | 12 (5.6) | 163 (76.7) | 36 (17) | 12 (5.7) | ||||

| Wirtz | 34 | 3 (8.8) | 27 (79.4) | 10 (32.3) | |||||

| Total | 925 | 13 (1.4) | 536 (57.9) | 66 (7.1) | 24 (2.6) | 189 (20.4) | 24 (2.6) |

Spaces left blank indicate no reported data pertaining to intravenous medicines.

Quality of the evidence extracted

Studies were evaluated for validity and reliability of methods used to detect error. Retrospective studies all used spontaneous error reports; therefore, it cannot be assured of having captured all possible errors and error types. There was also a predominance of administration errors reported in these studies, suggesting a reporting bias to only those clinically significant events. All prospective studies used the disguised observation approach, but measures to ensure validity of detection were mixed. Only one study (Ghaleb) stated that data collection tools had been piloted and validated prior to commencing the study. Three studies all used the same methodology (Taxis, Wirtz and Cousins)19 21 24 with a standardised data collection tool, but these methods all reported using a single trained observer in each site, therefore are weak to observer bias. It is notable that all data collectors in the included studies were pharmacy professionals, and their role and experience in intravenous medication administration was uncertain in all papers.

Most studies reported strategies to ensure the reliability of the data collected, with training offered to all data collectors. However, multicentre studies used different observers, and no study reported any evaluation of inter-observer variation and reliability. Severity was assigned to errors in a single study (Narula)16 using a readily available tool (NCC MERP) and agreed by consensus.

Discussion

Approximately 10.1% of intravenous medication administrations are associated with an error. The most common administration error identified in this review is ‘wrong rate’ errors, which account for 57.9% of reported errors. ‘Wrong time’ errors are the second most common with 20.4% of reported errors. However, the available studies are of low quality.

Insufficient data were available to estimate the severity of these errors, and there were no studies of the economic impacts of these errors. The epidemiology and aetiology of medication errors are multifactorial and poorly understood, and we believe that this is the first systematic review specific to intravenous medication administration errors in the UK. This review is timely in that it comes after the publication of the Department of Health review of the prevalence of medication errors in the NHS in England.25

The results in this review appear to present a high incidence of medication administration error that contradicts reports based on NRLS data.24 However, it is acknowledged that incidents reported via NRLS represent only between 5% and 15% of actual incidents,24 and it is noted that those studies using direct observation identified more errors. Furthermore, those studies on the prevalence of intravenous medication administration errors have demonstrated an increase in reporting habits among healthcare providers. Ross et al 18 found 0.32/1000 pbd reported errors, while both Narula and Thomas reported an eightfold higher prevalence likely related to improved reporting cultures implemented after the publication of Ross’s study and driven by NHS policy.26 Rates of spontaneous reporting have been correlated with improved safety.27

Moreover, the results of this focused review broadly align with the findings of other work. Elliott et al 25 identified that medication administration errors account for 54% of medication errors overall in England. Furthermore, Elliott’s review identified the elderly and children and young people as at-risk groups. Additionally, that review also failed to identify any economic evaluations of medication error. Our review was not designed to identify risk groups; however, it is important to note that four of the eight included studies were focused on children and young people. Additionally, our estimate of intravenous medication error compares favourably with a recent study published after our search was executed. Lyons et al undertook a multicentre prospective observational study in 16 centres across the UK.28 Observing 2008 infusions they identified errors in 11.5% of administered infusions and discrepancies in 53%. Twenty-three errors were considered to be potentially harmful. This study used a pragmatic definition of errors, with minor or intentional deviations from policy (including infusion rate variations and documentation omissions) considered ‘discrepancies’. However, this definition has not been used in previous error research and may have resulted in a low estimate of the incidence of errors. However, the definitions used in the studies in this review were broad and heterogeneous so it is also plausible that our estimate is perhaps higher than the true incidence. This goes to demonstrate the methodological difficulties inherent in error research as the very definition of medication error is controversial.

The NHS recognises that intravenous medication is a challenge for patient safety and has moved to drive healthcare organisations to work towards improving reliability29; however, current interventions to improve safety are targeted at prescribing and preparation of intravenous medications.30 In light of this review and given that the majority of administration errors are associated with wrong infusion rates and infusion times, and errors associated with preparation appear to be relatively low, then interventions to mitigate this large group of errors should be considered. Furthermore, Lyons’ 201828 study observed a wide variation in organisational intravenous policies and procedures that was a familiar qualitative finding reported in a number of studies included in this review. Standardisation of these procedures and policies may help improve intravenous infusion safety. Moreover, programmable infusion drivers that automatically calculate dose and rate are already available on the market and are considered effective at reducing medication errors if we can drive this standardisation of intravenous administration processes.31

This review is not without its limitations. Our tightly focused review question has undoubtedly limited our search field. Only being interested in those studies from the UK reduced our opportunities for synthesis. For example, a study that included error data from the UK in a pooled analysis of European medication errors, where the UK data were not readily identifiable did not meet our inclusion criteria.32

Systematic reviews of medication error aetiology are often complicated by the heterogeneity in study design inherent in this field. However, the commonality of denominators and data collection methods in prospective studies has enabled some limited synthesis to assess overall incidence of errors. Comparison of our review with other empirical studies provides some assurance that our estimates are not grossly discordant with other research. However, we must observe that a single study (Ghaleb et al)22 included in the synthesis did not clearly differentiate intravenous from non-intravenous observed administrations. Therefore, it is possible that our incidence is an underestimate. However, the study was seminal and highly cited thus was included for completeness, accepting the impact that this had on the final estimate. Additionally, the heterogeneity of studies reporting prevalence of errors in the UK has not permitted any synthesis and conclusions relating to this outcome cannot be drawn other than to comment on improved error reporting.

We recommend that further research into improving intravenous medication safety be focused on the aetiology of intravenous administration errors, the economic impact of these errors and the cost effectiveness of interventions to reduce their incidence, particularly those associated with incorrect rate of administration.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS conceptualised the review. MC executed the literature search and strategy. All authors participated in the data extraction and had material input into the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have had sight of the final manuscript and agreed to its content.

Funding: BD funded the development of the literature search strategy and database search through Laser Core (la-ser.com).

Competing interests: AS reports personal fees and non-financial support from Becton Dickinson UK Ltd. during the conduct of the study. JC, MR, TS and EW all report personal fees from Becton Dickinson UK Ltd. during the conduct of the study.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Department of Health. The Report of the Short Life Working Group on reducing medication-related harm. London 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/medication-errors-short-life-working-group-report (accessed 15 Mar 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation. Medication Without Harm - Global Patient Safety Challenge on Medication Safety. Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maddox RR, Danello S, Williams CK, et al. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008. Intravenous infusion safety initiative: collaboration, evidence-based best practices, and “smart” technology help avert high-risk adverse drug events and improve patient outcomes http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21249948 (accessed 18 Mar 2018). [PubMed]

- 4. Parshuram CS, To T, Seto W, et al. Systematic evaluation of errors occurring during the preparation of intravenous medication. CMAJ 2008;178:42–8. 10.1503/cmaj.061743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ECRI Institute. Top 10 health technology hazards for 2017 named. OR Manager 2017;33:24–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP List of High-Alert Medications in Acute Care Settings. Horsham, Pennsylvania, 2014. http://www.ismp.org/Tools/highalertmedications.pdf (accessed 18 Mar 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ohashi K, Dykes P, McIntosh K, et al. Evaluation of intravenous medication errors with smart infusion pumps in an academic medical center. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2013;2013:1089–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rinke ML, Bundy DG, Velasquez CA, et al. Interventions to reduce pediatric medication errors: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014;134:338–60. 10.1542/peds.2013-3531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vijayakumar A, Sharon EV, Teena J, et al. A clinical study on drug-related problems associated with intravenous drug administration. J Basic Clin Pharm 2014;5:49–53. 10.4103/0976-0105.134984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alsulami Z, Choonara I, Conroy S. Paediatric nurses' adherence to the double-checking process during medication administration in a children’s hospital: an observational study. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:1404–13. 10.1111/jan.12303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trbovich PL, Pinkney S, Cafazzo JA, et al. The impact of traditional and smart pump infusion technology on nurse medication administration performance in a simulated inpatient unit. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:430–4. 10.1136/qshc.2009.032839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arenas-López S, Stanley IM, Tunstell P, et al. Safe implementation of standard concentration infusions in paediatric intensive care. J Pharm Pharmacol 2017;69:529–36. 10.1111/jphp.12580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cousins DH, Sabatier B, Begue D, et al. Medication errors in intravenous drug preparation and administration: a multicentre audit in the UK, Germany and France. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:190–5. 10.1136/qshc.2003.006676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD, et al. The incidence and nature of prescribing and medication administration errors in paediatric inpatients. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:113–8. 10.1136/adc.2009.158485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Narula P, Hartigan D, Puntis JWL. The frequency and importance of reported errors related to parenteral nutrition in a regional paediatric centre. E Spen Eur E J Clin Nutr Metab 2011;6:e131–e134. 10.1016/j.eclnm.2011.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O’Hare MC, Bradley AM, Gallagher T, et al. Errors in administration of intravenous drugs. BMJ 1995;310:1536–7. 10.1136/bmj.310.6993.1536c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ross LM, Wallace J, Paton JY. Medication errors in a paediatric teaching hospital in the UK: five years operational experience. Arch Dis Child 2000;83:492–7. 10.1136/adc.83.6.492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taxis K, Barber N. Ethnographic study of incidence and severity of intravenous drug errors. BMJ 2003;326:684 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas AN, Taylor RJ. An analysis of patient safety incidents associated with medications reported from critical care units in the North West of England between 2009 and 2012. Anaesthesia 2014;69:735–45. 10.1111/anae.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wirtz V, Taxis K, Barber ND. An observational study of intravenous medication errors in the United Kingdom and in Germany. Pharm World Sci 2003;25:104–11. 10.1023/A:1024009000113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Dean Franklin B, et al. What constitutes a prescribing error in paediatrics? Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:352–7. 10.1136/qshc.2005.013797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Co-ordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 1996. About medication errors http://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors (accessed 15 Feb 2016).

- 24. Cousins DH, Gerrett D, Warner B. A review of medication incidents reported to the national reporting and learning system in england and wales over 6 years (2005-2010). Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:597–604. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04166.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elliott R, Camacho E, Campbell F, et al. Prevalence and Economic Burden of Medicaton Errors in the NHS in England. Sheffield, UK, 2018. http://www.eepru.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/medication-error-report-revised-final.2-22022018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chief Medical Officer. An Organisation With a Memory. London, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edmondson AC. Learning from failure in health care: frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:ii3–ii9. 10.1136/qshc.2003.009597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyons I, Furniss D, Blandford A, et al. Errors and discrepancies in the administration of intravenous infusions: a mixed methods multihospital observational study. BMJ Qual Saf 2018:bmjqs-2017-007476 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Reporting and Learning Service. Safety Alert 20: Promoting safer use of injectable medicines, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keers RN, Williams SD, Cooke J, et al. Causes of medication administration errors in hospitals: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Drug Saf 2013;36:1045–67. 10.1007/s40264-013-0090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rothschild JM, Keohane CA, Cook EF, et al. A controlled trial of smart infusion pumps to improve medication safety in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2005;33:533–40. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000155912.73313.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, et al. Errors in administration of parenteral drugs in intensive care units: multinational prospective study. BMJ 2009;338:b814 10.1136/bmj.b814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE, et al. Medication error prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children’s hospitals. Pediatrics 1987;79:718–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thomas A. Patient safety incident review information. gt. manchester crit. care major trauma netw. http://gmccn.org.uk/patient-safety-review (accessed 6 Apr 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2018-001624supp001.pdf (99.2KB, pdf)