Abstract

The popularity of yoga in the United States and across the globe has been steadily increasing over the past several decades. The interest in yoga as a therapeutic lifestyle tool has also grown within the medical community during this time. However, the wide range of styles available to the public can make it difficult for patients and physicians alike to choose the one that will offer the most benefit. This guide was created to assist physicians in making informed recommendations for patients practicing yoga in the community. When the most suitable style is selected, yoga can be an extremely useful lifestyle tool for patients seeking to improve fitness and develop a mindfulness-based practice.

Keywords: yoga, mindfulness, elderly, disabled, accessible, fitness

‘Many health professionals express an interest in practicing yoga or learning more about it but are discouraged by the multitude of subtypes and lack of time.’

Our own experiences and education can help inform our patients and our practices. When I was introduced to yoga, I had been running between 35 and 70 miles a week for the previous 6 years. My body ached constantly, and I was often stiff and sore. I had very little flexibility—I certainly could not bend over and touch my toes from standing. So when I began my yoga practice, it was uncomfortable to say the least. I was quite surprised, then, how quickly my body began to evolve when I was practicing a few times a week. I saw better range of motion in my hips and shoulders, less stiffness, and less stress. Without trying, I lost nearly 15 pounds over the subsequent year, which I believe resulted from the mindfulness I developed from my practice and how I applied this toward eating. My interest in yoga continued to grow, and eventually, I underwent training to become an instructor. After 7 years, I can confidently say that teaching has also shaped me as a health professional. Watching people move in my classes has shown me how injuries and illnesses can limit a person’s movement patterns and ultimately the ability to function. Yoga also improved my communication skills by giving me feedback in real time about whether I was explaining well enough for people to translate my instructions into action. I believe the benefits of yoga for health professionals are immense—it not only has the potential to improve the health of the provider but of the provider’s patients as well through education and recommendations. Many health professionals express an interest in practicing yoga or learning more about it but are discouraged by the multitude of subtypes and lack of time. This guide is developed as an introduction to help practitioners understand some of the most popular styles of yoga.

Introduction

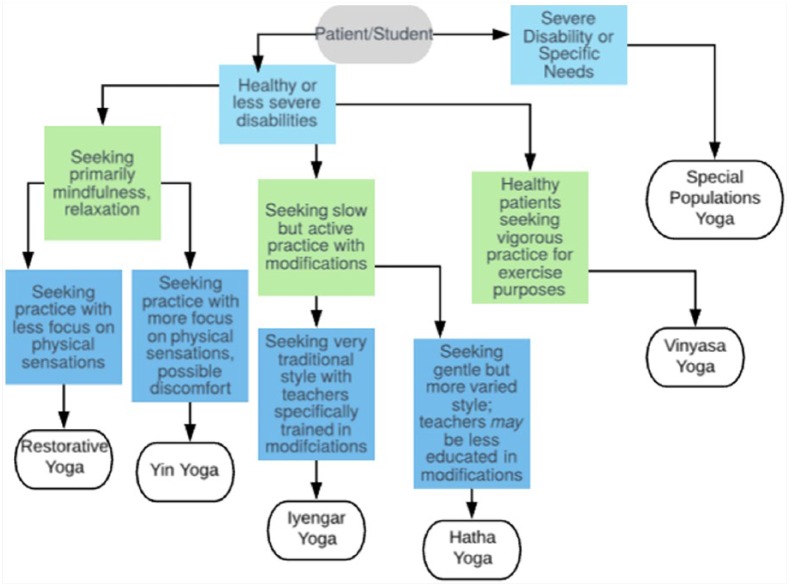

An estimated 36.7 million Americans practiced yoga in 2016, a number that has grown 50% since 2012.1 Interest in yoga has also grown within the health care community; a search for the term yoga on PubMed yields more than 4000 results. With growth in both popularity and research to support the practice of yoga, it is important for physicians to be able to advise their patients appropriately. With well over a dozen styles of yoga, however, it can be difficult to decipher what is best for each individual patient. Some styles are quite rigorous, even acrobatic, whereas others are performed seated in a chair. The following is a brief guide to assist in making informed recommendations for patients practicing yoga in the community. Please note that this guide is by no means comprehensive, nor does it cover dogmatic principles or traditions of each style; rather, it discusses only some of the most commonly practiced styles of yoga from a functional perspective and options for patients with varying levels of physical abilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm for recommending yoga.

Gentle Yoga

For students who are seeking a yoga practice that is more focused on mindfulness and less focused on movement, a restorative or yin class may be most appropriate. Both restorative yoga and yin yoga are gentle styles of yoga that are suitable for a very wide range of students of various ages and levels of ability. These classes move slowly. In a 90-minute class, students may practice as few as 7 to 10 postures. Restorative yoga has been shown to decrease chronic low back pain in service members.2 Another study suggests that yoga has a beneficial effect on depression in African American breast cancer survivors.3 Restorative yoga is focused on the students’ comfort and relaxation. Students are fully supported by yoga props (blocks, straps, blankets, bolsters, etc) in each posture to avoid discomfort, and the intention is to experience minimal physical sensation. Yin yoga, on the other hand, does not always use props and can be quite challenging. Though both styles are passive, discomfort is sometimes welcomed in a yin yoga practice, and students tend to experience more intense physical sensations from being in the postures. A yin yoga practice has been correlated to decreased levels of stress and worry, as well as increased mindfulness.4

Active but Accessible Styles

For students seeking an active practice where they can expect to build strength and flexibility, but may also need to modify postures because of injury or disability, an accessible style such as Iyengar or Hatha may be suitable. B. K. S. Iyengar brought his style of yoga to the West in the 1970s, developed from Ashtanga yoga principles but evolving to meet the specific accessibility and therapeutic needs of various individuals. Certified Iyengar yoga instructors must undergo years of training in order to become qualified. Iyengar students begin by learning the primary postures, most of which are standing postures, and later advance to bends, twists, and inversions. Iyengar prides itself on being a style of yoga that is accessible to people of all shapes, sizes, ages, and abilities. This style of yoga is well known for its extensive use of props (ie, chairs, straps, blankets) to assist students into postures. Instructors are trained to modify nearly any posture to meet the needs of the individual student. Iyengar yoga has been studied in several populations, including the elderly,5 those with chronic low back pain,6 breast cancer survivors,7 those with cardiac conditions,8 and more.

Hatha yoga, under which most forms of Western yoga can be classified, is another potentially suitable style for students seeking an active yet moderately accessible practice. This style of yoga is perhaps the most well studied, and research to date has suggested several possible benefits, including an increase in executive function,9 mental health,10 and physical fitness.11 Hatha simply refers to the practice of physical yoga postures, so technically Power yoga, vinyasa, Ashtanga, and Iyengar are all Hatha yoga. However, in reality, most yoga classes described as “Hatha” are characterized by gentle, basic postures and are not vigorous or sweaty. Most yoga studios have class descriptions, which can verify whether this is the case for their particular “hatha” classes. In general, hatha is excellent for beginners who wish to work on alignment, strength, and flexibility. Although these classes tend to be slower paced and gentler than other styles, students do need to be relatively healthy and able-bodied to participate. Additionally, whereas teachers of this style will be able to recommend modifications for many postures, they may not be trained to work with students with disabilities.

Vigorous Styles

Vinyasa yoga is the most popular style of yoga in the world today, but it encompasses many different traditions. The reality is that “vinyasa” classes can be very different depending on the individual studio offering the class. There are many subtypes of yoga that fall under the umbrella of vinyasa, two of which are described below. In general, vinyasa is a vigorous style of yoga, and it has been demonstrated to meet criteria for moderate-intensity physical activity.12 These styles require students to have a general level of health and fitness, and students should seek advice from their physician if they are unsure of their suitability to practice. Because there is a “flowing” component that requires moving up and down frequently, these styles will increase heart rate and respiratory rate. Postures in these styles can range from beginner friendly to very advanced. These are the styles that may offer acrobatic postures (ie, handstands) and those that require high levels flexibility (ie, the splits, backbends). Patients should be encouraged to practice these styles at their level of ability and to keep in mind that some of these postures may result in injury if performed incorrectly. As with most styles of exercise, those who practice avidly may experience repetitive strain injuries. In yoga, these injuries often occur to the shoulders and wrists, but students may have other musculoskeletal complaints as well.13

Often described as the origin of vinyasa, traditional Ashtanga yoga is taught “Mysore style,” where students practice at their own pace and learn posture by posture as a teacher moves around the room giving individual assistance. There are several increasingly advanced “series” of Ashtanga, the high levels of which take years to achieve and are only performed by the most advanced practitioners. Ashtanga is an athletic style of yoga, many postures of which are taken and practiced in other vinyasa style classes such as Power yoga. Power yoga tends to draw athletes and other students looking for a demanding practice. It is physically challenging and specifically designed to build strength and endurance. It is often practiced in a heated room (approximately 90°F) and thus is not suitable for students who are sensitive to changes in temperature. Power yoga should not be confused with other styles of hot yoga, such as Bikram yoga, which is a nonvinyasa style featuring 26 static postures practiced in a 105°F room.

Special Populations Yoga

There exist several programs and classes for specific populations. Although these classes are most commonly found in hospitals and rehabilitation facilities, they can be found in the community as well. Teachers instructing these classes have undergone additional training to meet the needs of the specific group they are working with. Examples of these special populations include the following: traumatic brain injury patients, multiple sclerosis patients, stroke patients, amputees, cancer patients, spinal cord injury patients, and more. There also exist general “adaptive” or “accessible” yoga classes, which are suitable for persons with a broad range of disabilities. There are many organizations that can be found online and offer guides, trainings, and teacher lists for specific populations wishing to start a yoga practice.

Conclusion

There are many styles of yoga, the physical practice of which can vary enormously. Restorative and yin yoga are gentle styles, with very little movement and a focus on relaxation. Iyengar and hatha are examples of active (but often still accessible) styles of yoga, which may be suitable for students requiring modifications. Vinyasa yoga is a rigorous and athletic style of yoga best for healthy students seeking a physically demanding practice.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1. Macy D. 2016 Yoga in America study conducted by Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance. https://www.yogajournal.com/page/yogainamericastudy. Published April 13, 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

- 2. Highland KB, Schoomaker A, Rojas W, et al. Benefits of the restorative exercise and strength training for operational resilience and excellence yoga program for chronic low back pain in service members: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.08.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashing KT, Miller AM. Assessing the utility of a telephonically delivered psychoeducational intervention to improve health-related quality of life in African American breast cancer survivors: a pilot trial. Psychooncology. 2015;25:236-238. doi: 10.1002/pon.3823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hylander F, Johansson M, Daukantaitė D, Ruggeri K. Yin yoga and mindfulness: a five week randomized controlled study evaluating the effects of the YOMI program on stress and worry. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;30:365-378. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2017.1301189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dibenedetto M, Innes KE, Taylor AG, et al. Effect of a gentle Iyengar yoga program on gait in the elderly: an exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1830-1837. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams K, Abildso C, Steinberg L, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and efficacy of Iyengar yoga therapy on chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:2066-2076. doi: 10.1097/brs.0b013e3181b315cc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2011;118:3766-3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perna G, Borriello G. Faculty of 1000 evaluation for effect of yoga on arrhythmia burden, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the YOGA My Heart Study. F1000. 2013; 61:1177–82. doi: 10.3410/f.717985182.793473751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luu K, Hall PA. Hatha yoga and executive function: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:125-133. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taspinar B, Aslan UB, Agbuga B, Taspinar F. A comparison of the effects of hatha yoga and resistance exercise on mental health and well-being in sedentary adults: a pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:433-440. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rachiwong S, Panasiriwong P, Saosomphop J, Widjaja W, Ajjimaporn A. Effects of modified Hatha yoga in industrial rehabilitation on physical fitness and stress of injured workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:669-674. doi: 10.1007/s10926-015-9574-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sherman SA, Rogers RJ, Davis KK, et al. Energy expenditure in Vinyasa yoga versus walking. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14:597-605. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cramer H, Ostermann T, Dobos G. Injuries and other adverse events associated with yoga practice: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21:147-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]