Abstract

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the TNF family of cytokines, which can induce apoptosis in various tumor cells by engaging the receptors, DR4 and DR5. Bortezomib (Velcade) is a proteasome inhibitor that has been approved for patients with multiple myeloma. There is some experimental evidence in preclinical models that bortezomib can enhance the susceptibility of tumors to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. In this study, we investigated the effects of TRAIL-induced death using an agonistic antibody to the TRAIL receptor DR5 (α-DR5) in combination with bortezomib administered to mice previously injected with breast cancer cells (TUBO). This combination had some beneficial therapeutic effect, which was significantly enhanced by the co-administration of a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist (CpG). In contrast, single agent treatments had little effect on tumor growth. In addition, we evaluated the effect of combination with α-DR5, bortezomib, and CpG in the prevention/treatment of spontaneous mammary tumors in Balb-neuT mice. In this model, which is more difficult to treat, we observed dramatic antitumor effects of α-DR5, bortezomib and CpG combination therapy. Since such a mouse model more accurately reflects the immunological tolerance that exists in human cancer, our results strongly suggest that these combination strategies could be directly applied to the therapy for cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-010-0834-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast tumors, Balb-neuT mice, Bortezomib, α-DR5, CpG

Introduction

Apoptosis is the crucial hallmark for regulation of normal tissues and malignancy [7, 11]. Numerous strategies designed to induce tumor cell apoptosis are available in clinical trials, since resistance of tumor cells against apoptosis is a major obstacle in the treatment of cancer [8, 17]. One of the promising therapeutic strategies to eliminate tumor cells is via the triggering of proapoptotic death receptors [6]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a type II transmembrane protein belonging to the TNF family that triggers apoptosis on binding to its receptors, DR4 and/or DR5. Agonistic mAbs, α-DR4 and α-DR5 in humans or α-DR5 in mice, have been generated to develop novel cancer therapeutics that induce tumor cell death. Humanized versions of both α-DR4 and α-DR5 mAbs are currently in phase I clinical trials [9, 13, 22]. However, it is still controversial if the reagents such as recombinant TRAIL and agonistic mAbs of DR5 are hepatotoxic. Taketa et al. [26] have demonstrated an interesting observation that α-DR5 mAb injection induced cholangitis and hepatic injury by apoptosis of cholangiocytes in B6 mice, but not in Balb/c mice.

Recently, several agents have been described that sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. One of these agents, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade; PS-341), can sensitize various tumor cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by increasing the surface expression of DR4 and DR5 [3, 12, 25]. Bortezomib is an approved drug for treatment of patients with multiple myeloma [2, 10]. Several studies demonstrated that bortezomib alone or in combination with other therapeutic agents such as TRAIL induce apoptosis of tumor cells and inhibit tumor growth [24].

Using the experimental mouse breast carcinoma model, TUBO, we show here that the combination of bortezomib and α-DR5 mAb increases apoptosis of TUBO tumor cells in vitro and promotes tumor regression in vivo. However, combination therapy with bortezomib and α-DR5 did not completely eradicate tumor growth in this model. Since the ultimate goal of our work was to determine antitumor effects in the more aggressive spontaneous breast tumor model in Balb-neuT mice, we attempted to enhance this combination therapy by adding TLR-L (CpG). Injection of CpG has an immunostimulatory function and has previously been shown by our laboratory to produce antitumor effects in this model [20].

Although CpG is well known to act as an adjuvant for the innate immune response via the triggering of Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR 9) signaling pathway [16, 30, 32], the role of CpG on antitumor effects is relatively new and yet largely unknown [4]. Actually, one of the crucial studies regarding the antitumor effect of CpG was performed by our group [20]. In an attempt to provide complete tumor regression, we hypothesized that the addition of CpG to the bortezomib and α-DR5 combination therapy could enhance the efficacy of therapy in both the TUBO and Balb-neuT experimental models of breast cancer. Since bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor with multiple biological effects, it proved difficult to determine the optimal therapeutic window for combinations of bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG for tumor regression in the absence of substantial toxicity. We optimized both the doses for all three agents bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG, as well as the route of injection for the optimal therapeutic application of this combination.

In the present study, we demonstrated that a novel combination therapy involving a proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib), an agonistic monoclonal antibody to TRAIL receptor (α-DR5), and a Toll-like receptor agonist (CpG) could prevent tumor growth in both the TUBO as well as Balb-neuT tumor model.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female 6–8-week-old Balb/c mice were obtained through the National Cancer Institute/Charles River program. Mice were allowed to acclimate to our animal facility 1 week before beginning experiments. Balb-neuT mice (H-2 d) were bred in our facilities [5, 20]. Heterozygous 6- to 15-week-old virgin females expressing rat HER-2/neu, as verified by PCR, were used. All investigations followed guidelines of the Committee on the Care of Laboratory Animals Resources, Commission of Life Sciences, National Research Council. The animal facilities of the Moffitt Cancer Center are fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Cell lines

The TUBO (Turin-Bologna) tumor is a cloned cell line established in vitro from a lobular carcinoma that arose spontaneously in a Balb-neuT mouse [20]. 4T1-neu cells were produced by transfecting the Balb/c-derived 4T1 mammary tumor cells with a retrovirus encoding the rat neu gene [15] and were a generous gift of Dr. Zhaoyang You (University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA).

Reagents

Bortezomib (Velcade, PS-341) was kindly provided by Dr. Thomas J. Sayers (Basic Research Program, SAIC-Frederick Inc., MD, USA), and additional bortezomib (Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) was purchased from the Moffitt Cancer Center Pharmacy. The immunostimulatory synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide ODN-1826 (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′), containing two CpG motifs (referred as CpG), was prepared by the Mayo Clinic Molecular Core Facility.

Antibodies

The α-DR5 mAb (MD5-1) was generated as previously described [27, 28]. We purified α-CD40 (clone; FGK 45), and α-41BB (clone; 3H3) monoclonal antibodies as described previously [1].

Induction of apoptosis and annexin V staining

The indicated amount of biotinylated MD5-1 was cross-linked with 5 μg/ml streptavidin (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) at 4°C overnight (24 well plate). The next day, cells (TUBO; 3 × 105, 4T1-neu; 1 × 105) were cultured in the presence (10 μg/ml) or absence of bortezomib for 24 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V (BD Pharmingen) in the presence of DAPI (Sigma) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Stained cells were immediately analyzed. Flow cytometry was performed using an LSRII cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software, version 8.5 (Tree Star, Ashlan, OR). The percent of specific apoptosis was calculated as follows: percent specific apoptosis = (apoptosis with α-DR5 – spontaneous apoptosis)/(100 − spontaneous apoptosis) × 100.

ELISpot (enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot) assay

To assess antigen-specific T-cell responses, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The spleen was removed from each animal and placed separately into complete RPMI, supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol and gentamicin. The tissues were minced and ground through a sterile mesh to obtain a single cell suspension. Cells were treated with ACK buffer for red blood cell lysis and were counted and resuspended at the stated cell concentration for the appropriate in vitro assay. For detection of CD8 T cells secreting IFN-γ, ELISpot assays were performed as described previously [1]. CD8 T cells from spleens were purified by positive selection using antibody-coated magnetic beads according to manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Responder (CD8-purified) cells were incubated at 3 × 105, 1 × 105 and 3 × 104 per well, together with 3 × 104 stimulator cells. For measurement of peptide responses, A20 cells were used in the presence of peptide (rNEUp66-TYVPANASL) or its absence. TUBO cells were used as a stimulator for tumor recognition. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 20 h, and spots (IFN-γ-producing cells) were developed as described by the ELISpot kit manufacturer (Mabtech, Inc., Mariemont, OH). Spot counting was done with an AID ELISpot Reader System (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany).

Tetramer staining

Splenocytes were obtained as described in ELISpot assay. PE-conjugated H-2Kd/rNEUp66 tetramer was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health Tetramer Facility (Emory University Vaccine Center). Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated MHC class II, PerCP Cy5.5-conjugated CD8a (eBioscience; San Diego, CA) and PE-conjugated H-2Kd/rNEUp66 tetramer for 30 min. After washing three times with 1% BSA/PBS solution, flow cytometry was performed using an LSRII cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software, version 8.5 (Tree Star, Ashlan, OR).

Tumor challenge

Balb/c mice were challenged with either 3 × 105 TUBO cells or 2 × 105 TUBO cells s.c. Mice were monitored for tumor progression twice per week and euthanized when tumor size reached a size of 20 mm.

Prevention of spontaneous tumors

Virgin female Balb-neuT mice were selected by age to perform the combination therapy at different time points. To monitor the appearance of spontaneous tumors, the chests of the mice were shaved using an electric razor, and mammary pads were manually inspected twice every week. Data are also reported as tumor multiplicity (cumulative number of tumors per number of mice in each group) as previously described [20]. Measurable/palpable masses >2 mm in diameter were regarded as tumors. In all cases, when mice had tumors >20 mm in the greatest dimension or when skin ulceration occurred, they were euthanized by CO2 inhalation according to our institutional animal care and use committee guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was applied at 95% confidence interval to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups, with P < 0.05 being considered significant. All analysis and graphics were done using GraphPad Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Synergistic induction of apoptosis by bortezomib and α-DR5 mAb in vitro

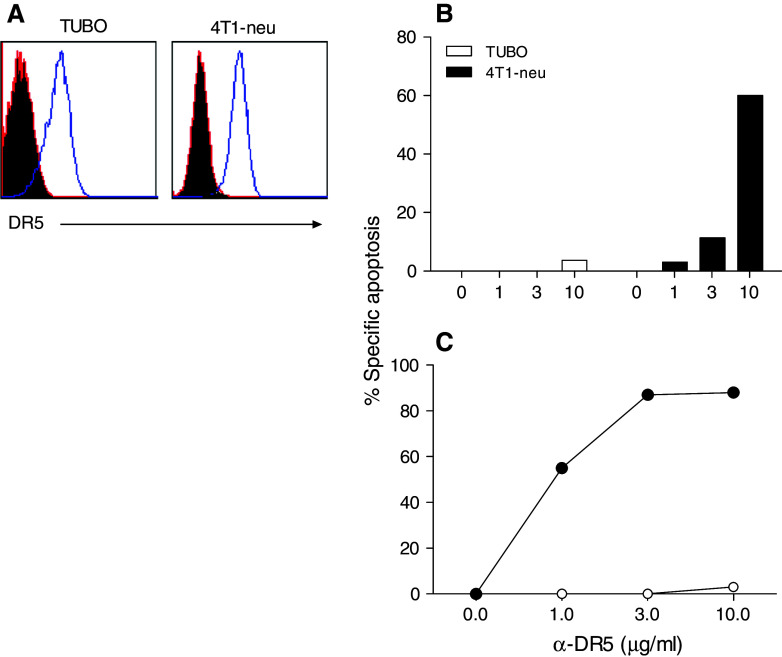

First, we measured the DR5 expression level on TUBO cells and compared it to its expression with the mouse breast cancer cell line 4T1, which has been known to be susceptible to TRAIL and α-DR5 mAb. As shown in Fig. 1a, TUBO and 4T1-neu (a rat NEU-transfected subline of 4T1), both expressed approximately equal levels of DR5 on their surface. Since our goal was to ultimately perform therapeutic studies with spontaneous tumors in Balb-neuT mice, we chose the TUBO cells that more closely resemble the spontaneous tumors for further studies. Since it is well known that cross-linking of DR5 is essential for induction of apoptosis [27], we evaluated whether TUBO cells were sensitive to α-DR5 mAb (MD5-1)-mediated cell death, as assessed by annexin V staining. For these experiments, we used biotinylated MD5-1 and streptavidin to cross-link the DR5. Unexpectedly, little apoptosis of TUBO cells was induced by MD5-1 alone (Fig. 1b), while incubation of 4T1-neu cells with MD5-1 alone for 24 h resulted in a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis.

Fig. 1.

Induction of apoptosis by α-DR5 and bortezomib. a DR5 expression on TUBO and 4T1-neu tumor cells. The indicated cell lines were stained with either PE-conjugated isotype control antibody (filled histogram) or PE-conjugated anti-DR5 antibody (open histogram). b TUBO cells (white bar) or 4T1-neu cells (black bars) were incubated with increasing concentration of α-DR5 alone. c TUBO cells were incubated with increasing concentration of α-DR5 alone (open circles) or in combination with bortezomib (10 μg/ml) (closed circles) for 24 h. Apoptotic cells were determined by annexin V staining. Percent specific apoptosis was calculated as described in “Materials and methods”

It has been reported that proteasomal inhibitors can increase the effectiveness of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in some tumor cells [11]. Thus, we examined whether treatment of the cells with bortezomib would increase the effects of the α-DR5 mAb in inducing apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 1c, incubation of TUBO cells with bortezomib and different doses of α-DR5 (closed circles) for 24 h resulted in enhanced apoptosis reaching a maximum of 90%, whereas α-DR5 alone (open circles) had little effect. Consequently, these results suggest that bortezomib and α-DR5 have a synergistic effect on the induction of apoptosis of TUBO cells in vitro.

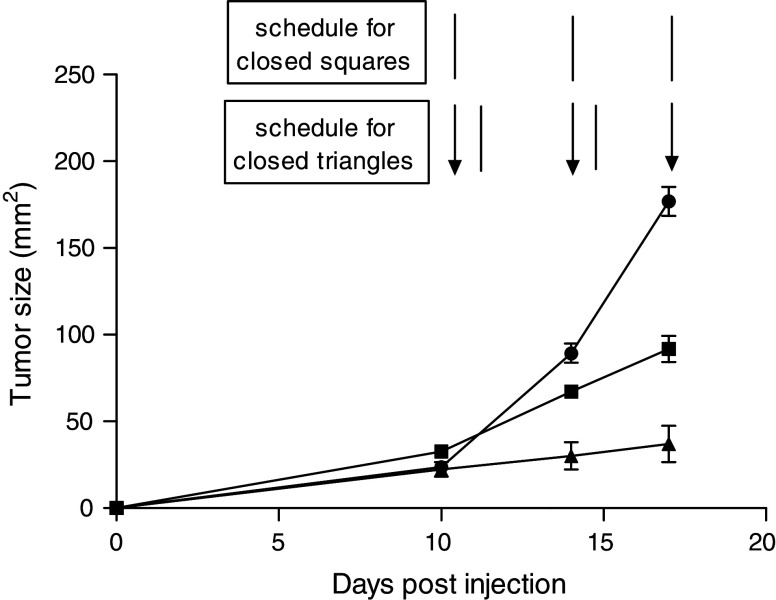

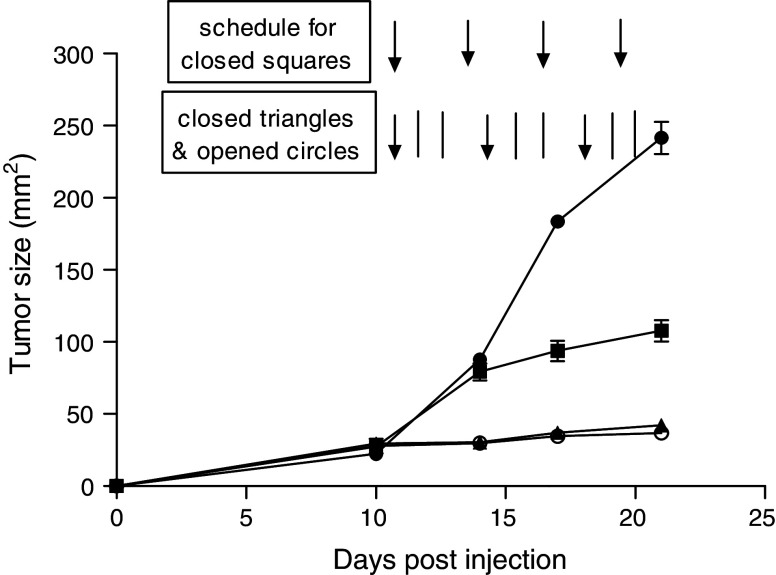

Partial regression of established tumor by combination therapy using bortezomib and α-DR5 mAb

In view of the above, we proceeded to determine whether α-DR5 mAb alone or in combination with bortezomib would have any effect on the growth of established TUBO tumors in Balb/c mice. α-DR5 mAb alone reduced the rate of tumor growth in all mice treated (Fig. 2, closed square) compared to the untreated mice (Fig. 2, closed circle. P < 0.05). More importantly, as predicted by the in vitro studies, a higher therapeutic effect was observed in those mice that received the bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb combination therapy (Fig. 2, closed triangle). However, we were not able to continue the treatment beyond day 17, since all the mice given bortezomib + α-DR5 perished probably due to the toxicity of bortezomib at this dose (2 mg/kg). Thus, for future experiments, we decreased the dose of bortezomib to 1 mg/kg per injection and, as shown in Fig. 3, bortezomib alone reduced the rate of tumor growth in all mice treated, as compared to the untreated mice (Fig. 3, closed square, P < 0.05). Notably, at this lower dose of bortezomib, two different doses of α-DR5 mAb (50 or 100 μg) further decreased tumor growth, but neither was able to induce complete tumor regression in this tumor model (Fig. 3, closed triangle and open circle). Nevertheless, using the low dose of bortezomib, toxicity was reduced and mice did not perish due to the treatment. Thus, for future experiments, we decided to use 50 μg of α-DR5 mAb and 1 mg/kg of bortezomib. Taken together, these results indicate that α-DR5 mAb had a therapeutic effect against an established TUBO breast tumor (5–7 mm) and such therapeutic effects could be further magnified by concomitant bortezomib treatment.

Fig. 2.

Partial regression of TUBO tumor after treatment with either α-DR5 alone or combination of bortezomib and α-DR5. Groups of mice were subjected to the following: injected with 3 × 105 TUBO cells on day 0; left untreated (n = 5, closed circles); given α-DR5 (50 μg per injection, i.v. route) for a total of three times every 4 days (lines) (n = 5, closed squares); given bortezomib (50 μg per injection, i.v. route) twice per week, with a 3-day break between injections (arrows) and α-DR5 (50 μg per injection, lines) the next day after bortezomib (n = 5, closed triangles). Significant differences (P < 0.02) between α-DR5 alone and bortezomib + α-DR5-treated mice were observed on day 14 and later. Data represent the results of a single experiment, which was one of three with similar results

Fig. 3.

Partial regression of TUBO tumor after treatment with bortezomib alone or combination of bortezomib and different doses of α-DR5. Groups of mice were subjected to the following: injected with 3 × 105 TUBO cells on day 0; left untreated (n = 5, closed circles); given bortezomib alone (25 μg per injection, i.v. route) for a total of three times every 4 days (arrows) (n = 5, closed squares); given bortezomib (25 μg per injection, i.v. route) twice per week, with a 3-day break between injections (arrows) and two injections of α-DR5 (50 μg per injection, i.v. route, lines) between bortezomib injections for two cycles (n = 5, closed triangles). Since we decreased the concentration of bortezomib from 50 to 25 μg, we were able to continue the treatment up to day 21 without toxicity. The injection protocol of mice (n = 5) shown by open circles was identical to those indicated by closed triangle, except for the α-DR5 dose (100 μg per injection, i.v. route). Tumor size (area in mm2) was calculated by multiplying two perpendicular diameters. P < 0.02 between α-DR5 alone (Fig. 2, closed triangles) and bortezomib + 50 μg of α-DR5 (closed triangles), α-DR5 alone (Fig. 2, closed triangles) and bortezomib + 100 μg of α-DR5 (open circles) on day 14 and later. P < 0.02 between bortezomib alone (closed squares) and bortezomib + 50 μg of α-DR5 (closed triangles), bortezomib alone (closed squares) and bortezomib + 100 μg of α-DR5 (open circles) on day 14 and later. Data represent the results of a single experiment, which was one of three with similar results

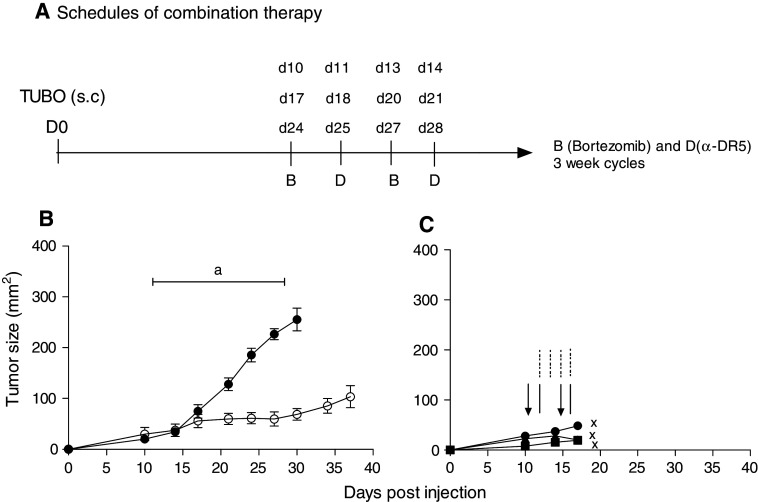

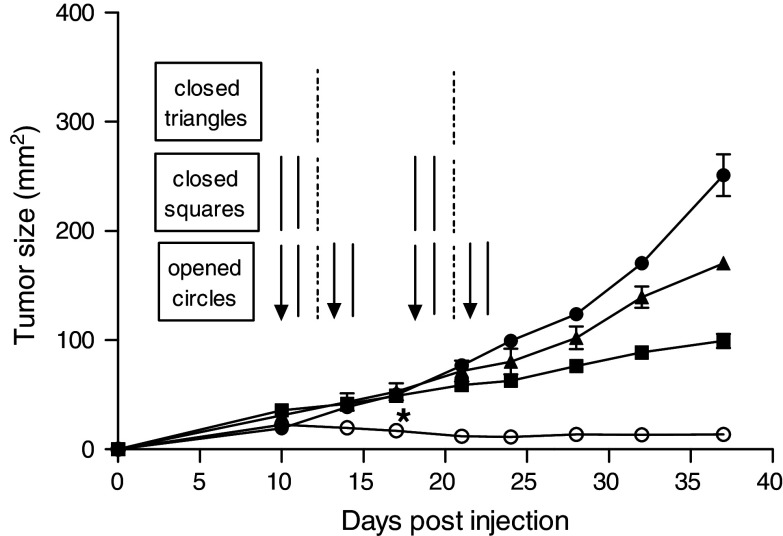

Next, we assessed the possibility of increasing the therapeutic efficacy of this combination therapy by the addition of a TLR-ligand (CpG), with the goal of completely eradicating the tumors. In these experiments, we included CpG (50 μg per injection s.c. route, four times per week) in the combination with bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb. The results presented in Fig. 4b show that the combination of bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb, as previously observed (Fig. 3), was effective in suppressing tumor growth, but the tumors were not completely eliminated even after prolonged treatment. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine whether CpG systemic therapy would enhance the therapeutic efficacy of bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb, because all mice died after four injections with CpG (Fig. 4c). We concluded that systemic treatment of CpG in combination with bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb was highly toxic and so we decided to lower the dose of CpG and administer it intratumorally as described previously [18]. To determine the presence of antigen-specific T-cell responses in group B, we euthanized all four mice and performed ELISpot assays as well as tetramer staining. However, we could not detect rNEU-p66-specific T-cell responses (data not shown). These results indicate that bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb can control, but not completely eradicate, tumors and that lack of eradication may be due to the absence of potent antitumor responses.

Fig. 4.

Tumor regression after treatment with a combination of bortezomib, α-DR5 and systemic CpG. Groups of mice were challenged with 2 × 105 TUBO cells on day 0. Mice (n = 5) indicated by closed circles were left untreated, and mice were euthanized at different time points based on the tumor size (over 20 mm). Group B and C were challenged with TUBO cells at the same time, but the treatments were different. B (n = 5, open circles) is bortezomib and α-DR5 treatment group. In graph, a indicates the period of treatment with bortezomib and α-DR5 for 3 weekly cycles. The treatment schedule is shown in a. Group C (n = 3) was given bortezomib (arrows), α-DR5 (lines) and CpG (dotted–dashed lines). CpG (50 μg per injection) was given systemically four times per week. All three mice died after treatment of 1 week because of toxicity. The time points were marked by X. Data represent the results of a single experiment, which was one of three with similar results

Complete regression of established tumors by the addition of CpG in the combination of bortezomib + α-DR5 mAb

As shown above, we have investigated several strategies to regress established TUBO tumor. We have shown that: (1) α-DR5 alone or bortezomib alone can induce partial regression in TUBO model. (2) α-DR5 + bortezomib induced partial regression in TUBO model. (3) α-DR5 + bortezomib + systemic CpG were too toxic to conclude about the effect on TUBO tumor. Next, we investigated whether the administration route of CpG can affect TUBO tumor regression. Thus, we changed the route of CpG from systemic to local (intratumoral) injection. Notably, the most significant effects in the TUBO model were observed in mice that received bortezomib, α-DR5 mAb and intratumoral CpG, but not intratumoral CpG alone, and α-DR5 and intratumoral CpG (Fig. 5). Although the α-DR5 + CpG-treated group showed partial regression compared to the control group, it was a trivial effect without the bortezomib combination. Thus, we concluded that the tumors in the bortezomib + α-DR5 + CpG-treated group regressed and appeared to have been eliminated completely.

Fig. 5.

Complete tumor regression after treatment with a combination of bortezomib, α-DR5 and intratumoral CpG. Balb/c mice were challenged with 2 × 105 TUBO cells on day 0. Groups of mice were subjected to the following: left untreated (n = 5, closed circles); treated with CpG alone (n = 5, closed triangle); treated with α-DR5 and CpG (n = 5, closed square); treated with bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG (n = 5, open circles). The schedules for treatment are indicated by arrows (bortezomib), lines (α-DR5) and dotted–dashed lines (CpG). P < 0.02 between control (closed circles) and bortezomib + α-DR5 + intratumoral CpG (open circles) on day 17 and later. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments

Antitumor activity of combination therapy against spontaneous tumors in Balb-neuT mice

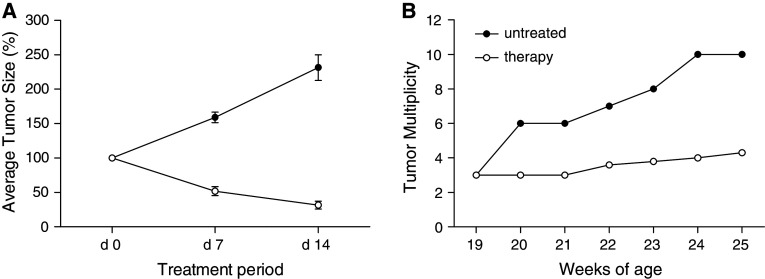

Though the TUBO tumor transplantation model is very useful to study the effects of combination immuno-chemotherapy, it does not reflect the natural progression of malignant disorders occurring in human cancer. Thus, we used female Balb-neuT mice, which express endogenously rat NEU in their mammary glands and develop multiple spontaneous tumors soon after reaching puberty [27], for further investigations on the effects of combination therapy using bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG. Thus, we assessed the effect of combination therapy in 19-week-old Balb-neuT female mice, which already had multifocal palpable carcinomas. Combination therapy with bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG was administered for a 2-week period. As shown in Fig. 6a, the combination therapy resulted in significant regression of the spontaneous tumor sizes (P < 0.01). Since the Balb-neuT mice contained multiple tumors at the start of therapy, we normalized the size of each tumor to 100% of the original size. The starting day of treatment was considered as a day 0. Accordingly, in untreated Balb-neuT mice, tumor size increased up to 280% from day 0 to day 14. Next, we calculated the average of percentage of regression of each tumor after finishing one cycle (day 7) and two cycles of treatment (day 14). Compared to untreated mice, the average size of tumors in mice given the combination therapy was reduced to about 50% on day 7 and up to 32% on day 14, respectively. In addition, the average number of tumors (tumor multiplicity) increased much faster in the untreated group compared to the group that was given combination therapy (Fig. 6b). We provide the individual tumor sizes in untreated or treated Balb-neuT mice as an additional supplemental figure (Fig. S1).

Fig. 6.

Antitumor effect in Balb-neuT mice by combination therapy with bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG. a Regression of tumor size in female Balb-neuT mice. Mice (open circles; n = 5) were given bortezomib (25 μg per injection, i.v. route), α-DR5 (50 μg per injection, i.v. route) and GpG (50 μg per mouse, i.t. route) as shown in Fig 5. Control mice were left untreated (closed circles; n = 5). All animals were monitored for tumor appearance by manual examination of the mammary glands every 5 days. Measurable masses >2 mm diameter were regarded as tumors. b Tumor multiplicity. The mean number of tumors per mouse in each group was calculated. Results were evaluated as described in a. P < 0.02 between untreated group and therapy group on day 7 and day 14 in a. P < 0.02 for comparison of untreated group with therapy group at 20 weeks and later in b. These experiments were repeated twice with similar results

Unfortunately, tumors inhibited by combination therapy started to grow after the 2-week treatment period (data not shown). However, such tumor growth in treated mice was significantly delayed until week 35, while control mice had to be euthanized by week 25 when at least one tumor had reached the 20-mm diameter size. Obviously, these results suggest that combination therapy using bortezomib, α-DR5 and CpG can be a useful therapeutic method to inhibit tumor growth and progression in Balb-neuT mice.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that a novel combination therapy including a proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib), an agonistic monoclonal antibody for TRAIL receptor (α-DR5) and a Toll-like receptor agonist (CpG) can diminish tumor growth in TUBO tumor model, as well as spontaneous tumors occurring in Balb-neuT mice. Recently, there are a few studies emphasizing the importance of bortezomib alone, α-DR5 alone or combination therapy in tumor models [3, 14, 25, 28, 31]. Although it has been known that bortezomib can sensitize a variety of tumor cells to the TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, not all tumor cells are sensitized [25]. Thus, we initiated this study to examine whether bortezomib could sensitize TUBO cells and furthermore prevent breast tumor growth in vivo.

Bortezomib is a potent proteasome inhibitor that is critical for protein degradation [19]. It has been already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of multiple myeloma [23]. Thus, many studies has been focused on this new drug, either alone or combined with other agents. Here, we first tried to use α-DR5 alone to determine if it has any inhibitory effect on TUBO cell lines. Unfortunately, we could not detect any apoptotic effect by annexin V staining in vitro. As expected, there was no effect in vivo when we tested the efficacy of α-DR5 alone in TUBO challenge model. In addition, no effect was observed in TUBO model when mice were treated with bortezomib alone. Since bortezomib has been shown to sensitize some tumors to TRAIL [24], we next examined the effect of a combination of bortezomib with an α-DR5 mAb to promote breast tumor cell death in vitro and in vivo. Bortezomib-induced sensitization of tumor cells to TRAIL has been reported to involve several molecular mechanisms as follows: (1) increased TRAIL receptors [24]; (2) decreased anti-apoptotic proteins such as c-FLIP and Bcl-2 [33]; (3) release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria [21]. Obviously, we have shown that bortezomib combined with α-DR5 induced apoptosis of TUBO cells in vitro. Furthermore, significant tumor regression was observed in vivo in the TUBO tumor model in response to the combination of bortezomib and α-DR5. However as we showed in our results, such tumor regression, although statistically significant, was incomplete. Last year, one interesting study was published while we were performing studies in the TUBO s.c tumor model. In this study, a combination therapy of bortezomib and α-DR5 was demonstrated to provide a beneficial therapeutic effect in both wild-type and SCID mice bearing the mouse renal cancer RENCA [29]. It was therefore concluded that the antitumor effect of this combination therapy directly involved molecular-targeted tumor cytotoxicity, but not an adaptive immune response. Actually, this study provided us with an interesting idea as to why combination therapy was not completely effective in our TUBO model. Thus, we considered modifying our combination strategy to include CpG in an attempt to further enhance any ongoing immune-mediated antitumor responses. There are several reasons for the addition of CpG in combination with bortezomib and α-DR5. First, it is possible that a lack of complete tumor regression using a combination of bortezomib and α-DR5 was due to a lack of immune response in our TUBO tumor model. Second, the role of CpG on antitumor effect is relatively new and unclear and worthy of further detailed investigation. Third, we needed a much stronger therapeutic effect than that observed with bortezomib and α-DR5, since the ultimate goal of the current study was to prevent tumor progression in a most aggressive spontaneous breast tumor model mimicking human tumor tolerance. Lastly, we are currently working on the effect of CpG in immune modulation as well as tumor regression.

Amazingly, the addition of CpG to combination of bortezomib and α-DR5 regress the tumor growth completely in the TUBO model as well as in the Balb-neuT model. Although we expected to obtain strong CD8 T-cell immune responses after CpG addition as a mechanistic study, we detected a small increase in the CD8 T-cell responses against rNEU p66 peptide in CpG-treated mice. The point that was missed in such an experiment was that we measured only the rNEU p66 peptide-specific CTL responses, since rNEU p66 is an immunodominant epitope for CTL. Thus, we could not detect significantly increased CD8 T-cell responses using a narrow window in the CpG-treated group. However, it is worthwhile to measure other immune responses mediated by CD4 cells and NK cells in future studies, because we only focused on rNEU p66-specific CD8 T-cell responses and may have missed other immune-mediated antitumor effects.

More interestingly, we have recently investigated DR5 expression on B16 melanoma cell line (unpublished personal result by S. Lee and E. Celis). Since one of the current focuses of our laboratory is the development of effective therapy against melanoma, this combination therapy may be applicable to enhancing therapeutic efficacy in melanoma tumor. For future consideration, it might be important to investigate the role of histone deacetylase inhibitors, NK cell-mediated tumor killing or depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells combined with our novel combination therapy in other tumor models. A better understanding of the control optimal administration and dose scheduling of these combination therapies may facilitate the rational development of new cancer vaccine candidates. These targeted therapies could reduce tumor burden, thus optimizing the benefit of immunotherapy on smaller tumors. In addition, the cytotoxic effects of these agents on tumor cells may promote the release of tumor antigens that under appropriate conditions may additionally increase antitumor immune responses.

Electronic supplementary material

Tumor growths for individual tumor in untreated or therapy treated virgin female Balb/neuT mice at different time points are illustrated in Fig. S1. Mammary pads were inspected twice every week to monitor tumor appearance. Measurable/palpable masses >2 mm in diameter were regarded as tumors. In all cases, when mice had tumors >20 mm in the greatest dimension or when skin ulceration occurred, they were euthanized by CO2 inhalation according to our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Figure S1. Individual tumor regression in Balb-neuT mice by combination therapy with bortezomib, α-DR5, and CpG. Control mice (N1 and N2) were left untreated. Mice (A, B, C, and D) were given bortezomib (25 μg per injection, i.v. route), -DR5 (50 μg per injection, i.v. route), and GpG (50 μg per mouse, i.t. route) as shown in Fig 5. All animals were monitored for tumor appearance by manual examination of the mammary glands every 5 days. Measurable masses > 2mm diameter were regarded as tumors (PPT 190 kb)

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, R01CA80782 and R01CA103921 (E. Celis), under contracts NO1-CO-12400 and HSN261200800001E (T. Sayers). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This Research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Assudani D, Cho HI, DeVito N, Bradley N, Celis E. In vivo expansion, persistence, and function of peptide vaccine-induced CD8 T cells occur independently of CD4 T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9892–9899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blade J, Cibeira MT, Rosinol L. Bortezomib: a valuable new antineoplastic strategy in multiple myeloma. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:440–448. doi: 10.1080/02841860510030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks AD, Ramirez T, Toh U, Onksen J, Elliott PJ, Murphy WJ, Sayers TJ. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade) sensitizes some human tumor cells to Apo2L/TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1059:160–167. doi: 10.1196/annals.1339.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpentier AF, Auf G, Delattre JY. CpG-oligonucleotides for cancer immunotherapy: review of the literature and potential applications in malignant glioma. Front Biosci. 2003;8:e115–e127. doi: 10.2741/934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho HI, Niu G, Bradley N, Celis E. Optimized DNA vaccines to specifically induce therapeutic CD8 T cell responses against autochthonous breast tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1695–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0465-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corazza N, Kassahn D, Jakob S, Badmann A, Brunner T. TRAIL-induced apoptosis: between tumor therapy and immunopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter TG. Apoptosis and cancer: the genesis of a research field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:501–507. doi: 10.1038/nrc2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter TG, Lennon SV, Glynn JG, Martin SJ. Cell death via apoptosis and its relationship to growth, development and differentiation of both tumour and normal cells. Anticancer Res. 1990;10:1153–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cretney E, Takeda K, Smyth MJ. Cancer: novel therapeutic strategies that exploit the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)/TRAIL receptor pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dicato M, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Harousseau JL, Ludwig H, San Miguel J, Sonneveld P. Management of multiple myeloma with bortezomib: experts review the data and debate the issues. Oncology. 2006;70:474–482. doi: 10.1159/000099284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green DR, Bissonnette RP, Cotter TG (1994) Apoptosis and cancer. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA (eds) Important advances in oncology. Lippincott, Philadelphia, pp 37–52 [PubMed]

- 12.Hallett WH, Ames E, Motarjemi M, Barao I, Shanker A, Tamang DL, Sayers TJ, Hudig D, Murphy WJ. Sensitization of tumor cells to NK cell-mediated killing by proteasome inhibition. J Immunol. 2008;180:163–170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao C, Song JH, Hsi B, Lewis J, Song DK, Petruk KC, Tyrrell DL, Kneteman NM. TRAIL inhibits tumor growth but is nontoxic to human hepatocytes in chimeric mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8502–8506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung L, Holle L, Dalton WS. Discovery, development, and clinical applications of bortezomib. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JH, Majumder N, Lin H, Chen J, Falo LD, Jr, You Z. Enhanced immunity by NeuEDhsp70 DNA vaccine is needed to combat an aggressive spontaneous metastatic breast cancer. Mol Ther. 2005;11:941–949. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:709–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna SL, Cotter TG. Functional aspects of apoptosis in hematopoiesis and consequences of failure. Adv Cancer Res. 1997;71:121–164. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng Y, Carpentier AF, Chen L, Boisserie G, Simon JM, Mazeron JJ, Delattre JY. Successful combination of local CpG-ODN and radiotherapy in malignant glioma. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:992–997. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monneret C, Buisson JP, Magdelenat H. A new therapy with bortezomib, an oncologic medicinal product of the year 2004. Ann Pharm Fr. 2005;63:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4509(05)82301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nava-Parada P, Forni G, Knutson KL, Pease LR, Celis E. Peptide vaccine given with a Toll-like receptor agonist is effective for the treatment and prevention of spontaneous breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1326–1334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nencioni A, Wille L, Dal Bello G, Boy D, Cirmena G, Wesselborg S, Belka C, Brossart P, Patrone F, Ballestrero A. Cooperative cytotoxicity of proteasome inhibitors and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in chemoresistant Bcl-2-overexpressing cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4259–4265. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newsom-Davis T, Prieske S, Walczak H. Is TRAIL the holy grail of cancer therapy? Apoptosis. 2009;14:607–623. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson PG. A review of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1321–1331. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanker A, Brooks AD, Tristan CA, Wine JW, Elliott PJ, Yagita H, Takeda K, Smyth MJ, Murphy WJ, Sayers TJ. Treating metastatic solid tumors with bortezomib and a tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor agonist antibody. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:649–662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanker A, Sayers T. Sensitizing tumor cells to immune-mediated cytotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:163–171. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda K, Kojima Y, Ikejima K, Harada K, Yamashina S, Okumura K, Aoyama T, Frese S, Ikeda H, Haynes NM, Cretney E, Yagita H, Sueyoshi N, Sato N, Nakanuma Y, Smyth MJ. Death receptor 5-mediated apoptosis contributes to cholestatic liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10895–10900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802702105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda K, Yamaguchi N, Akiba H, Kojima Y, Hayakawa Y, Tanner JE, Sayers TJ, Seki N, Okumura K, Yagita H, Smyth MJ. Induction of tumor-specific T cell immunity by anti-DR5 antibody therapy. J Exp Med. 2004;199:437–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uno T, Takeda K, Kojima Y, Yoshizawa H, Akiba H, Mittler RS, Gejyo F, Okumura K, Yagita H, Smyth MJ. Eradication of established tumors in mice by a combination antibody-based therapy. Nat Med. 2006;12:693–698. doi: 10.1038/nm1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanOosten RL, Griffith TS. Activation of tumor-specific CD8+ T Cells after intratumoral Ad5-TRAIL/CpG oligodeoxynucleotide combination therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11980–11990. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner H. Interactions between bacterial CpG-DNA and TLR9 bridge innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:62–69. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang H, Fox JA, Totpal K, Aikawa M, Dupree K, Sinicropi D, Lowe J, Escandon E. Enhanced tumor killing by Apo2L/TRAIL and CPT-11 co-treatment is associated with p21 cleavage and differential regulation of Apo2L/TRAIL ligand and its receptors. Oncogene. 2002;21:3611–3619. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Nojima Y, Umemori K, Phalen S, McMurray DN, Kuramoto E, Iho S, Takauji R, Sato Y, Yamada T, Ohara N, Matsumoto S, Goto Y, Matsuo K, Tokunaga T. Discovery of immunostimulatory CpG-DNA and its application to tuberculosis vaccine development. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W, Chen S, Liu X, Yue P, Sporn MB, Khuri FR, Sun SY. c-FLIP downregulation contributes to apoptosis induction by the novel synthetic triterpenoid methyl-2-cyano-3, 12-dioxooleana-1, 9-dien-28-oate (CDDO-Me) in human lung cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1614–1620. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.10.4763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Individual tumor regression in Balb-neuT mice by combination therapy with bortezomib, α-DR5, and CpG. Control mice (N1 and N2) were left untreated. Mice (A, B, C, and D) were given bortezomib (25 μg per injection, i.v. route), -DR5 (50 μg per injection, i.v. route), and GpG (50 μg per mouse, i.t. route) as shown in Fig 5. All animals were monitored for tumor appearance by manual examination of the mammary glands every 5 days. Measurable masses > 2mm diameter were regarded as tumors (PPT 190 kb)