Abstract

Background

Leishmania spp. are digenetic parasites capable of infecting humans and causing a range of diseases collectively known as leishmaniasis. The main mechanisms involved in the development and permanence of this pathology are linked to evasion of the immune response. Crosstalk between the immune system and particularities of each pathogenic species is associated with diverse disease manifestations. Lipophosphoglycan (LPG), one of the most important molecules present on the surface of Leishmania parasites, is divided into four regions with high molecular variability. Although LPG plays an important role in host-pathogen and vector-parasite interactions, the distribution and phylogenetic relatedness of the genes responsible for its synthesis remain poorly explored. The recent availability of full genomes and transcriptomes of Leishmania parasites offers an opportunity to leverage insight on how LPG-related genes are distributed and expressed by these pathogens.

Results

Using a phylogenomics-based framework, we identified a catalog of genes involved in LPG biosynthesis across 22 species of Leishmania from the subgenera Viannia and Leishmania, as well as 5 non-Leishmania trypanosomatids. The evolutionary relationships of these genes across species were also evaluated. Nine genes related to the production of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor were highly conserved among compared species, whereas 22 genes related to the synthesis of the repeat unit presented variable conservation. Extensive gain/loss events were verified, particularly in genes SCG1-4 and SCA1-2. These genes act, respectively, on the synthesis of the side chain attached to phosphoglycans and in the transfer of arabinose residues. Phylogenetic analyses disclosed evolutionary patterns reflective of differences in host specialization, geographic origin and disease manifestation.

Conclusions

The multiple gene gain/loss events identified by genomic data mining help to explain some of the observed intra- and interspecies variation in LPG structure. Collectively, our results provide a comprehensive catalog that details how LPG-related genes evolved in the Leishmania parasite specialization process.

Keywords: Genome mining, Leishmania, Lipophosphoglycan, Phylogenomics, Trypanosomatids

Background

The Leishmania spp. are protozoan parasites belonging to the family Trypanosomatidae. These microorganisms are digenetic, spending a portion of their life-cycle in an invertebrate host and another part in a vertebrate host. During these stages, the morphology and metabolism of the parasite changes drastically. Mammalians are one of the vertebrate hosts inhabited by the parasite, and, when bitten by an infected sand fly vector (Diptera: Phlebotominae), Leishmania promastigotes are inoculated into the blood pool in the mammalian hostʼs dermis along with sand fly saliva once the mosquito takes a blood meal [1, 2]. Once inside the host, parasites, which are phagocytosed by immune cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, assume a rounded shape and transit into amastigote forms, which are highly adapted to the phagolysosomal milieu [3, 4]. With regard to the sand fly vector (e.g. Lutzomyia spp. and Phlebotomus spp.), Leishmania parasites inhabit the midgut and differentiate into promastigote. Thereafter, the parasites migrate to the pharyngeal valve. The specific binding site and migration course in the phlebotomine gut varies in accordance with parasite species. For instance, species of the subgenus Viannia, e.g. L. (Viannia) braziliensis, remain in the hindgut and then migrate to the midgut, while species of the subgenus Leishmania, e.g. L. (Leishmania) infantum, develop in the posterior midgut and subsequently reach the anterior midgut [5].

The manifestations caused by Leishmania infection are collectively termed leishmaniasis and are responsible for serious public health problems in many poor-income countries [6]. The resulting clinical presentation is dependent on Leishmania species, as well as parasite interplay with the host immune system. In humans, leishmaniasis manifestations range from cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL) is characterized by ulcers of different sizes at the site of inoculation, while mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (ML) affects the skin and mucosae. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the most severe and life-threatening form, where the parasite diffuses through the bloodstream, reaching essential organs, such as the liver and spleen, and eventually bone marrow [7–11].

Lipophosphoglycans (LPGs), the main glycoconjugate found on the surface membranes of Leishmania parasites, are constitutively expressed in promastigote forms, while low expression levels are seen in amastigotes [12]. LPG is also a virulence factor that participates directly in parasite attachment and establishment within the sand fly midgut, where vector lectins interact with the lateral chains of LPG repetition units [13]. This lipophosphoglycan can also delay lysosome fusion with the phagosome and disrupt the assembly of NADPH oxidase on the phagosomal membrane [14].

The LPGs are composed of four elements: (i) a phosphatidylinositol anchor; (ii) a conserved (core) glycan group consisting of β-linkages between galactose, mannose, and glucosamine; (iii) phosphoglycan repeating (PG) units (Gal β1,4 Man α1-PO4), which are, in some cases, associated with side chains; and (iv) a neutral oligosaccharide called cap [15, 16]. Variations in the composition and length of these structures, particularly the side chain and cap regions, are evidenced among parasite species and morphological forms (amastigotes or promastigotes) [17]. Although previous reports have described several genes related to LPG biosynthesis, the pathway as a whole has not been entirely elucidated and is known to involve multiple metabolic sub-routes [18–21].

The present study endeavoured to identify the repertoire of genes involved in LPG production by Leishmania using a comprehensive data mining approach combining genomic, transcriptomic and high-quality primary literature searches. All findings were supported by extensive manual curation and annotation of genomic search results. Moreover, the evolutionary relationships between the identified genes were evaluated. Our results allow for an improved understanding regarding how LPG-related genes were shaped during the evolutionary diversification of Leishmania parasites to different vectors, disease manifestations and geographical ranges.

Methods

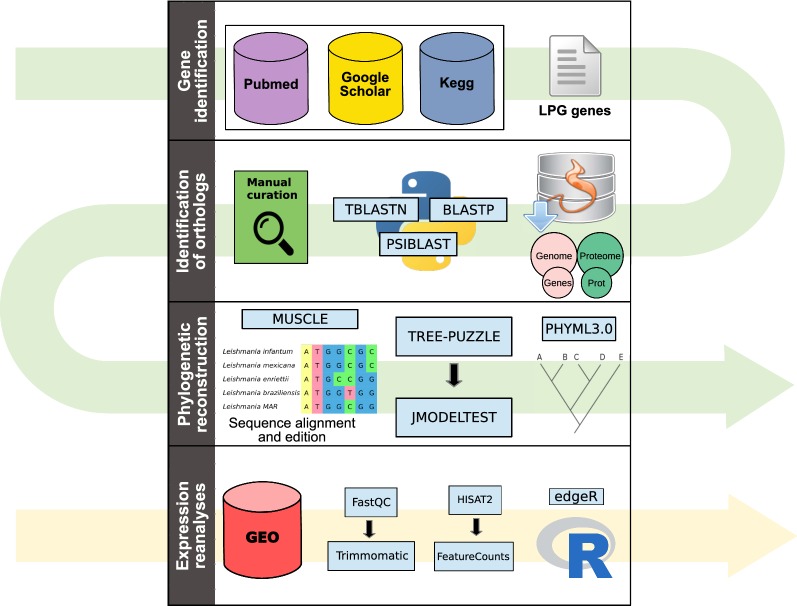

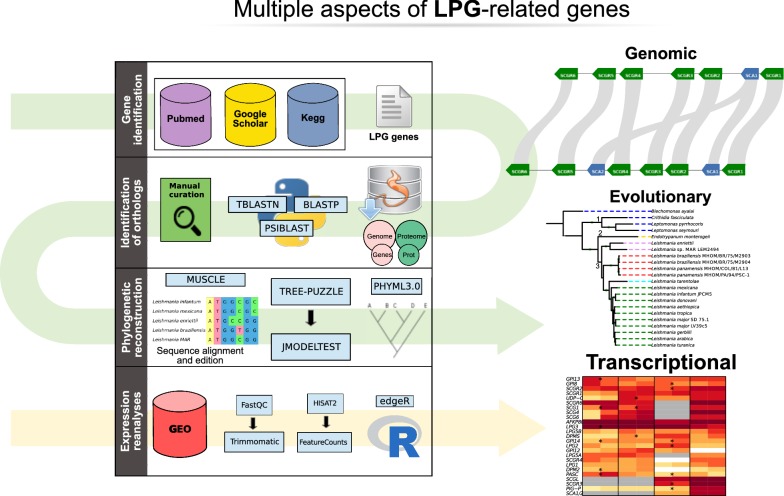

The current study employed multiple computational techniques in order to derive a set of LPG-related genes across various trypanosomatids. Particularly, we used genomic data mining, phylogenetic analyses and re-evaluation of selected RNA-seq datasets, which are summarized in Figure 1, and further described in the following sections.

Fig. 1.

Scheme summarizing the steps of the methodology. In order to determine the catalog of genes related to LPG synthesis, searches were performed in three databases (primary literature (NCBI/PubMed; Google Scholar) and metabolic information (KEGG)). To establish orthology relationships, the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of these genes were obtained from TriTrypDB along with 22 genomes and proteomes of trypanosomatid species. To evaluate the similarity between these sequences, three variants of the BLAST algorithm were used, and the execution of these sequences was performed using a custom-tailored Python script and subsequently curated, yielding groups of ortholog genes across species. The phylogenetic reconstruction was performed from the alignment of the groups using Muscle, and the evaluation of phylogenetic signal in the groups was performed with Tree-Puzzle. The most informative evolutionary model was estimated with jModelTest2 and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using PHYML

Identification of the catalog of genes related to LPG biosynthesis from the primary literature

To determine the set of genes related to LPG synthesis, we used the primary literature (articles indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar) in which experimentally characterized protein sequences were reported. Textual searches were performed using Boolean operators and the keywords: “LPG biosynthesis” AND “Leishmania”. In addition, searches using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) database [22] were performed, particularly using the pathway maps related to the GPI anchor synthesis (KEGG accession map00563). TriTrypDB (http://tritrypdb.org) [23] was also used as an information source, facilitating the retrieval of genes, genomes and proteomes from the organisms used in this study. This allowed the identification of gene names, gene families, and molecular functions that relate to the synthesis of LPG in these organisms. Once identified, the genes were downloaded from TriTrypDB using Leishmania major Friedlin as a reference organism [23] along with the complete genomes and proteomes (when available) of the species included in the study (Additional file 1: Table S1). A total of 27 organisms were included, most of them (n = 22) from the genus Leishmania (excluding L. amazonensis due to the absence of a chromosome-level genome assembly). Also studied were the genomes of other non-Leishmania trypanosomatids, including Blechomonas ayalai (n = 1), Crithidia fasciculata (n = 1), Leptomonas spp. (n = 2), and Endotrypanum monterogeli (n = 1). Their inclusion allowed to study LPG-related genes from an evolutionary standpoint given the more basal position of these organisms. Genomes of Trypanosoma spp. were not included in the study due to the low similarity of the majority of studied LPG-related proteins in these organisms, which is in agreement with the reported lack of lipophosphoglycan in their surface, despite the presence of other surface molecules such as variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs) [24].

Inference of LPG orthologs across multiple trypanosomatids

From the high-quality gene set determined in the previous step, sequence similarity searches were performed in locally created BLAST databases [25] comprising proteome or genome sequences from the studied organisms, using L. major Friedlin genes as queries from the previous step. For this purpose, the BLASTP (protein search against proteome), TBLASTN (protein search against genome), and PSI-BLAST (search of distant proteins against proteome iteratively) suite of algorithms included in the BLAST+ 2.7.1 package [26] were used to conduct similarity searches. Particularly, phylogenetically more distant orthologs (which have accumulated more changes, for example, or are present in organisms with more divergent evolutionary history) were retrieved using PSI-BLAST with up to five iterations. Orthology was defined by visually inspecting the alignments and considering the following properties: sequence identity, coverage (minLrap and maxLrap), and genomic context conservation (synteny). Coverage and identity criteria of 60% and 80%, respectively, were used as guides during the manual curation, albeit these cut-offs were relaxed for some proteins when comparing more distant organisms with evidence such as strong synteny support and domain conservation. Custom Python scripts (http://www.python.org) were written to automatically perform large-scale BLAST analyses, calculate coverage statistics from the text outputs, perform initial filtering steps that classified each queried protein as present or absent in an organism, and prepare tabular outputs. These results were then manually curated. For SCG family genes, which present extensive sequence conservation and locate in telomeric regions [27], we additionally employed the Mauve algorithm v2.4.0 [28] to resolve their position and identity, which helped to assign a correct gene annotation. Coverage statistics were calculated as follows: , where L1 and L2 are the lengths of two compared proteins.

Reconstruction of maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees

The phylogenetic reconstruction of genes identified in the previous step was performed to infer the evolutionary history and within-family relationships between the different species. For this analysis we concatenated genes according to each LPG structural region. Genes that had a high level of conservation (having a single ortholog in each species) were divided into groups considering the structure of the LPG in which it exerted its metabolic function (anchor genes or repeat unit genes) and later concatenated into single sequences corresponding to each species. Gene multiple alignment was carried out using Muscle version 3.8.31 [29] followed by manual curation of the alignments [30]. Phylogenetic signal was determined by Tree-Puzzle 5.2 [31], with the likelihood mapping approach. For the maximum likelihood tree identification, the PhyML [32] version 3.3.20180621 was used with the model GTR+I+G, selected by employing the Akaikeʼs information criterion within jModelTest 2.1.10 program [33]. The tree support indexes were determined by bootstrap with 1000 replicates. The trees were edited using FigTree v1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and iTol [34].

Evaluation of the expression of LPG-related genes

In order to find transcriptional evidence for the identified genes, a reanalysis of previously published transcriptomic datasets deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA/NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) was performed. Datasets were selected based on the comparison of different Leishmania life stages, and for which transcriptome profiling using RNA-seq methodology was available [35–37]. These included promastigote and amastigote samples for L. mexicana [36] and L. donovani [35] in axenic cultures; and L. major and L. amazonensis during metacyclic promastigote stage as well as intracellularly 4 h and 48 h post-macrophage infection [37]. The sequence accessions of these samples are listed in Additional file 2: Table S2. To avoid methodology bias, all sequences were reanalyzed using the same integrated pipeline, as follows: first, FastQC was used to perform read quality-control (QC) [38]. Then, filtering of low-quality sequences and adapter trimming were performed using Trimmomatic v. 0.38 (parameters: LEADING:3; TRAILING:3; SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20; and MINLEN:70) [39]. HISAT2 v. 2.1.0 [40] was used to map the reads that passed QC against the genomes of L. donovani BPK282A1, L. major Friedlin and L. mexicana MHOM/GT/2001/U1103, which were obtained from TriTrypDB version 42. Due to the low quality of the L. amazonensis MHOM/BR/71973/M2269 genome, reads from this species were mapped against the genome of L. mexicana MHOM/GT/2001/U1103. FeatureCounts v. 1.6.3 was used to obtain a gene count table [41], and edgeR was employed to perform normalization of the expression data using the trimmed mean of M-values method (TMM) [42]. TMM-normalized counts per million (cpm) values were obtained for each gene, and to facilitate comparison across different experiments and conditions, the expressional level of each LPG-related gene was discretized into deciles. Non-parametric tests were used to evaluate differences across life forms and parasite species using as input the normalized cpm values. For two-sample comparisons, the Mann–Whitney test was used, while for three-sample comparisons the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed followed by Dunnʼs post-hoc test, and significance was considered when P-values were less than 0.05.

Results and discussion

Building a catalog of genes related to lipophosphoglycan biosynthesis in trypanosomatids

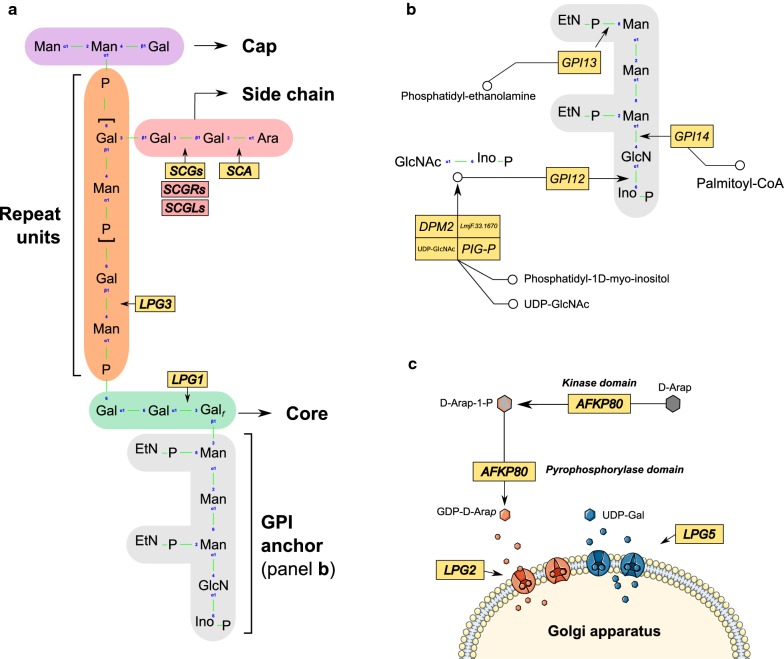

The first step in our study was to perform searches in primary literature databases for genes associated with LPG synthesis. As a result, we identified 9 genes associated with glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis (belonging to the anchor and core regions) and 22 genes related to the repeat unit assembly, totaling 31 genes. The selection of genes that were studied in the present study participate in diverse biochemical reactions that lead to the synthesis of LPG. These include the addition of molecules into the core and repeat unit (Fig. 2a), GPI anchor (Fig. 2b), and transport of these molecules (Fig. 2c). Events of gain/loss of LPG genes observed across the compared trypanosomatids could lead to diversity in the structure of LPG in these organisms.

Fig. 2.

A metabolic map related to LPG synthesis in Leishmania. a The LPG molecule, composed of four main parts (GPI anchor, core, repeat unit and cap). The branched polysaccharide residues that usually compose this molecule are shown, and the sites where LPG-related gene products act for the synthesis of this molecule are displayed together with the gene name in yellow boxes. SCGR/L family genes proposed to participate in side chain formation are highlighted in salmon boxes. Genes that are involved in the synthesis of the repeat unit and core regions are shown, while those that form the GPI anchor appear in b. c The conversion of d-arap into GDP-d-Arap by the dual kinase/pyrophosphorylase activity of AFKP80, and the transport of GDP-d-Arap and UDP-Gal into the Golgi apparatus. Abbreviations: Ara, arabinose; d-Arap, d-arabinopyranose; EtN, ethanolamine; Gal, galactose; Galf, galactosylfuranose; GlcN, glucosamine; GlcNAc, N-acetyl glucosamine; Ino, inositol; Man, mannose

The search for these genes used as a query the Leishmania major Friedlin genome, as this strain offers superior quality of sequencing and annotation data within the reported trypanosomatids. The accession numbers, genomic location, and protein products for the 31 LPG-related genes are shown in Additional file 3: Table S3. These genes were queried using multiple variations of the BLAST algorithm within the genomes/proteomes of the studied trypanosomatids. The TriTrypDB database was the primary information source, and related metadata (including stable accessions, genome size, G + C%, and gene count) are available in Additional file 1: Table S1. Sequence alignments were thoroughly manually curated in order to evaluate duplications, frameshifts and any other possible rearrangements. Figure 1 summarizes the data processing workflow and methodology.

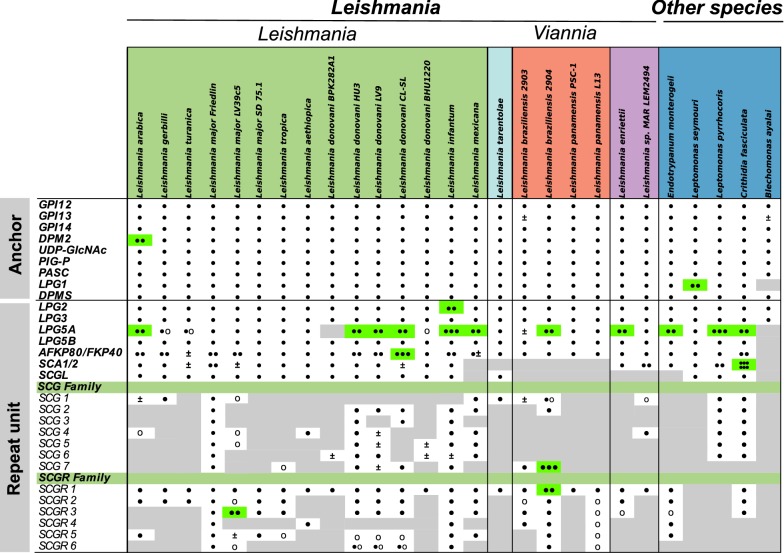

Once a curated dataset was obtained, we summarized the repertoire of LPG-related orthologs identified by our whole-genome mining strategy in the 26 queried organisms compared to L. major Friedlin (Fig. 3). A total of 549 proteins were recovered, 16 sequences were re-annotated (from being previously annotated as hypothetical proteins; listed in Additional file 4: Table S4), and 22 open reading frames (ORFs) were newly predicted as a result of our analyses (Additional file 4: Table S4). Information on these sequences, including protein products and corresponding ORF coordinates, are available in Additional file 5: Table S5. The 31 LPG-related genes were then grouped based on the metabolic processes in which they participate, i.e. either the synthesis of the GPI anchor region or the repeat unit. The following sections provide further details regarding the results related to each synthesis region.

Fig. 3.

A catalog of trypanosomatid genes involved in the synthesis of LPG. The genes in each row are grouped by their involvement in the synthesis of molecules in either the anchor or repetition regions of LPG. FKP40 and AFKP80, as well as SCA1 and SCA2 genes were jointly considered because of their high degree of sequence conservation that hampers their differentiation by sequence analysis alone. Species belonging to the L. enrietti complex are marked in purple in the top panel, and those belonging to Sauroleishmania in light blue. The subgenera Leishmania and Viannia are shown in green and red, respectively. For retrieved sequences, the following symbols were used to indicate the presence of an ortholog for the gene (●), frameshift within the gene (±), and sequences with a partial alignment (o). Events of gene gain and loss are represented in green and gray, respectively. The sequences used as query for the BLAST searches were from L. major Friedlin. Presentation of the data was inspired by the previous genome-based work of Arcá et al. [73]

Genes involved in GPI molecule biosynthesis are mostly conserved and well-distributed among trypanosomatids

The repertoire of LPG-related genes in Figure 3 revealed a high degree of conservation in genes related to GPI-anchor biosynthesis among the compared parasites. This stability in gene content was not unexpected, given that the GPI-anchor structure is well-conserved across species and represents the building block upon which a series of sugar molecules are anchored, such as glycosylinositolphospholipids (GIPLs) and GP63 [43–45]. Despite this sequence conservation, some exceptions were observed. For instance, in the genome of L. braziliensis MHOM/BR/75/M2903, the GPI13 gene ortholog (coding for ethanolamine phosphate transferase 3) presented a frameshift generated by a deletion at position 102,951 of chromosome 24 that gave rise to two ORFs: LBRM2903_240008400, with a length of 1365 bp, and LBRM2903_240008500, located 63 bp downstream with a size of 1497 bp that starts at position 103,018. Both had nucleotide identities of approximately 78% to the L. major query. Considering this similarity, the degree of conservation and the importance of this gene, as well as the presence of the complete ortholog in the related strain MHOM/BR/75/M2904 (Fig. 3), it is plausible that this frameshift likely stemmed from a sequencing error. The sequencer used to obtain this genome, Roche 454 FLX, supports this hypothesis, given its proneness to insertion/deletion (InDel)-type errors. Another exception is our result for the LPG1 gene, which lacked a corresponding ortholog in the genome of Blechomonas ayalai (a monoxenous species of flea parasites), which also appeared duplicated in Leptomonas seymouri, a monoxenous parasite capable of infecting mammals under specific circumstances (e.g. an immunocompromised host) [46]. This gene is vitally important to the structure of LPG, as it encodes a galactosylfuranose transferase responsible for the Galf (β1,3) Man binding, with specific activity in the LPG core; in its absence, the remaining structure of the LPG molecule cannot be correctly assembled. A possible explanation for the lack of LPG1 in B. ayalai might be its more phylogenetically distant position from all other species included in this study. The paralogs identified in L. seymouri may accomplish distinct activities, similarly to what was also observed for homologs of this gene found in the genome of L. major Friedlin, which exert functions unrelated to LPG synthesis (e.g. LPG1G family members that participate in the production of GIPLs) [18]. The differentiation of other galactosylfuranoses from LPG1-like sequences is more straightforward in Leishmania, as these organisms possess a high degree of conservation in their genomic contexts, but this becomes more complicated when more distant species, such as Leptomonas, are analyzed. In this context, what could be construed as a duplication event could also represent a functionally distinct coding sequence. The fact that LPG1 was present in almost all of the studied organisms, together with its importance to the synthesis of LPG, makes it an attractive object of study across various Leishmania species, as has been performed in L. major, L. infantum and L. donovani using knock-outs of this gene [47, 48].

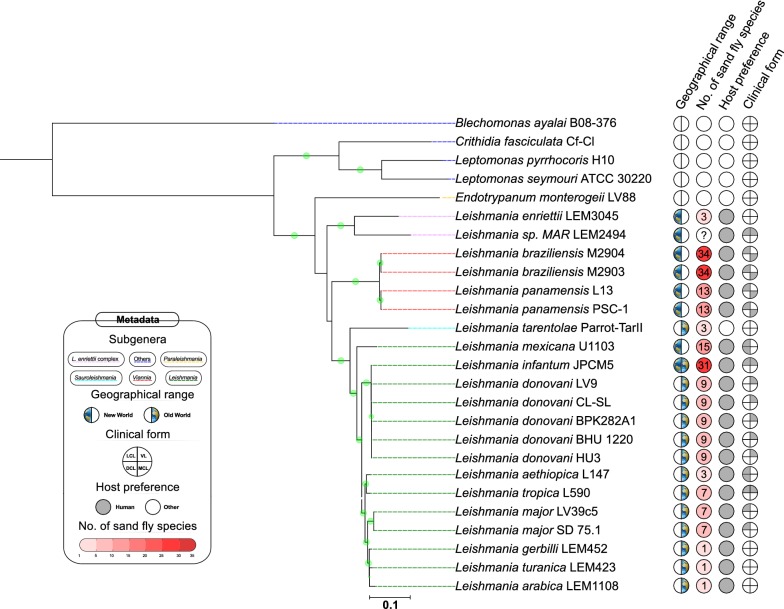

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with all concatenated orthologs of the genes related to the synthesis of the anchor region (Fig. 4). This analysis provided an overview of the evolutionary history of GPI-anchor related genes, as this structure is required for the binding of several membrane compounds of Leishmania. Figure 4 also shows data on the geographical region in which each species is endemic, as well as clinical manifestations (when pathogenic) and host candidates. The clusters observed in this tree follow the subgenera classification of trypanosomatid species, while also differentiating between New and Old World Leishmania species. Of note, the robust bootstrap support for most of the identified clusters indicates that the choice of genes used to perform this analysis was appropriate. Within the Euleishmania lineage, the most basal cluster is formed by species of the L. enriettii complex, and this clade is further subdivided into taxa belonging to the subgenera Viannia and Leishmania. Interestingly, this phylogenetic placement is consistent with other studies that used an even higher number of genes [49], indicating that the set of GPI-anchor genes studied here recapitulate the key features of Leishmania evolution. It is worth noting that the three Leishmania species that do not cause disease (L. arabica, L. gerbilli and L. turanica) were grouped into a single cluster (Fig. 4). The observed evolutionary pattern was also linked to geographical range (L. gerbilli and L. turanica are found in Central Asia, South Mongolia and Iran, and L. arabica in Saudi Arabia) and to the number of sand fly vectors. The relatedness of this group with that of L. major (Fig. 4) also favors this idea, since the same vector also transmits this species. The presence of LPG-specific receptors in the sand fly midgut supports the notion that similarities among GPI-anchor genes in Leishmania are driven more by shared vector characteristics than by vertebrate host species preference [50].

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic maximum likelihood tree representing the evolutionary history of concatenated genes related to GPI anchor biosynthesis. Bootstrap values (1000 replications) greater than 80% are represented by a green circle in the branches of the tree. The right-hand panel classifies species according to their geographical range, number of sand fly species reported to act as vector for each parasite (at the species level), host preference and clinical form of the disease for species that are infective for humans. Colored dashes indicate the subgenus for each species, with those not classified into this taxonomic rank grouped as “Others”. The metadata were extracted from Akhoundi et al. [74]

Genes participating in the synthesis of the repeat unit present variable conservation and extensive gain/loss events across compared species

Most of the genes related to the synthesis of the PG (Gal-Man-PO4) region (LPG2, LPG3, LPG5A, and LPG5B) had orthologs identified in the studied organisms, with many gene gain/loss events observed (Fig. 3). All the genes except for LPG3 code for nucleotide-sugar transporters (NST), proteins responsible for transporting the nucleotide-sugars synthesized in the cytoplasm to the Golgi lumen or the endoplasmic reticulum, both organelles that participate in LPG assembly [21, 51]. LPG2 encodes a GDP-mannose transporter, a key carrier for supplying the substrate necessary for PG synthesis. Knockouts of this gene in L. donovani and L. major resulted in the complete absence of PGs [19, 52]. A single copy of this gene was found in all studied organisms, exception for L. infantum JPCM5, for which a recently published genome re-sequencing effort involving long PacBio reads revealed the presence of two tandem gene arrays that include copies of LPG2 [53], in contrast to the original genome sequence which harbored a single copy of this gene. This leads us to speculate that the same may be true for other Leishmania species, which should be considered as an important factor that may preclude attempts to develop mutants for these genes using traditional recombination techniques [54].

LPG5A and LPG5B are genes responsible, at least in L. major, for the transport of UDP-galactose. LPG5A is involved in the pathway that synthesizes the PGs present in LPG as well as its side chain, while LPG5B participates in the PG biosynthesis of PPG, another component of the Leishmania membrane. Both genes were included in our analysis because their double knockout was shown to result in a complete absence of PGs [21]. While LPG5B occurs as single-copy in all species in which an ortholog of this gene was identified (except for B. ayalai), several gain events were observed for LPG5A, especially in L. infantum (three duplications), L. mexicana, L. braziliensis MHOM/BR/75/M2904, as well as L. donovani genomes HU3, LV9 and CL-SL, all harboring two copies of this gene. The absence of an LPG5A ortholog in L. donovani BPK282A1 is noteworthy. Further study is warranted regarding the implications of this extensive repertoire of NST in these organisms, as Leishmania spp. are known for using gene dosage as a mechanism to increase transcriptional activity at both single-gene and chromosomal levels [55]. The duplication events identified in this study could be an effect of these types of mechanisms to shape variability in the membrane components of these parasites.

Another monosaccharide important to the structure of LPG is arabinose in its dexter form, with a ring containing six carbon molecules known as d-Arabinopyranose (d-Arap). This molecule participates directly in parasite detachment from the sand fly midgut via transfer to the end of the galactose side chain [56]. When capped with d-Arap, this region loses its affinity to the lectins present in the intestinal mucosa, resulting in parasite detachment and subsequent migration to the upper portion of the intestinal tract [56–58]. However, for d-Arap to be inserted into this structure, it must first be associated with the GDP molecule, a process that involves piro- and phosphorylation catalyzed by the protein encoded by AFKP80. This complex is then transported by LPG2 to the Golgi complex, where it becomes available to arabinotransferases encoded by SCA1 and SCA2 [59]. A paralog of AFKP80 (termed FKP40) was identified in the genome of L. major Friedlin with a 99.75% identity, differing by only three amino acids in the N-terminal located in the enzymatic domain responsible for pyrophosphorylase activity. This minor variation was sufficient to provoke the loss of its pyrophosphorylase action [59]. Due to the high degree of conservation between this gene and its paralog, our search for orthologs of AFKP80 or FKP40 was conservatively defined in order to identify any of their possible orthologs, which is why both genes appear collapsed in Figure 3. We observed that the majority of studied New World Leishmania, as well as the non-Leishmania trypanosomatids included, have only one of the paralogs coded in their genomes, whereas most of Old World Leishmania present two paralogs. Another phylogenetic tree containing the hitherto discussed genes (LPG2, LPG3, LPG5A, LPG5B, AFKP80/FKP40) responsible for repeat unit synthesis was constructed (data not shown), showing similar topology to that built using the GPI anchor genes (Fig. 4).

Since the arabinotransferases SCA1 and SCA2 are absent in several species of Leishmania, particularly those of the subgenus Viannia, e.g. L. braziliensis and L. panamensis (Fig. 3), this suggests that these species are dependent on a distinct mechanism for detachment from the gut that is not linked to arabinose. The fact that these species bind to the hindgut at the beginning of sand fly infection, and not to the midgut as seen in parasites of the subgenus Leishmania, may help explain the absence of these genes [1]. An exception is L. mexicana, since the genome of this species does not code for SCA representatives despite belonging to the subgenus Leishmania (Fig. 3). Studies to determine the existence of residues of d-Arap in the glycoconjugates of the above-cited parasites, as well as their function, will help shed light on these divergent findings. In addition, SCA/SCGL genes could potentially function as markers of specific leishmaniasis presentations, such as VL. In Brazil, L. infantum, along with L. amazonensis, and in rare cases, L. braziliensis, is responsible for the visceral manifestation of leishmaniasis [60, 61], with around 3500 cases reported annually [62]. The fact that we identified SCA genes exclusively in L. infantum provides evidence that these could present a possible target for identifying the causative species in VL cases using molecular biology techniques, such as PCR. Six SCA orthologs were recognized in Crithidia fasciculata (Fig. 3), perhaps because this species bears an LPG-like membrane compound termed lipoarabinogalactan (LAG), which harbors d-galactan-bound arabinose residues in its structure [63, 64].

While gene members of the SCG/R/L family (SCG1-7, SCGR1-6, and SCGL), 14 in all, have the predicted function of galactosyltransferases, a study by Dobson et al. [27] found that SCG1-4 were the only ones that exhibited β(1-3)-galactosyltransferase activity in the side chain of L. major Friedlin LPG. Nonetheless we included all of the genes in this family in our study, as they are likely all transcribed in stable messenger RNAs, with variable patterns of expression at different parasite life stages. Although only a few presented confirmed activity, the remaining members were also considered as having the potential to encode active glycosyltransferase enzymes [27].

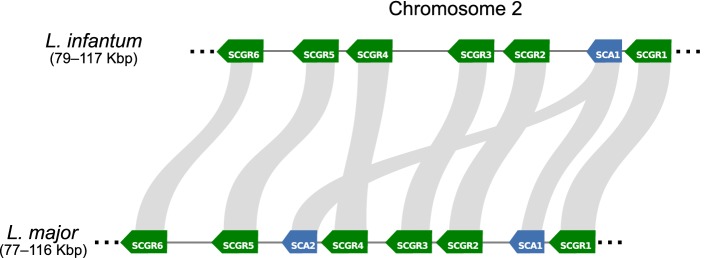

In L. major Friedlin, the SCG1-7 genes are distributed among multiple chromosomes (7, 21, 36, 31, 35, 25 and 2, respectively), and are always located in the telomeric region, while the genes belonging to the SCGR family were all found in chromosome 2 in a cluster interspersed by the SCA1-2 genes (Fig. 5). In L. major, we identified the location of SCGL in an internal region of chromosome 14, 38 kbp distant from the right telomere; in the other Leishmania investigated herein, when orthologs were present, they were also located in this chromosome. Our search for orthologs revealed a highly variable conservation level in these genes (Fig. 3), which leads us to the conclusion that their β(1-3)-galactosyltransferase function might be specific to only a few species. This variability was not unexpected, as the structures present in the side chains are particular to each species/strain, with different carbohydrates and structural modifications previously described by others [65, 66].

Fig. 5.

Synteny plot of SCGR1-6 genes and SCAs genes between L. major Friedlin and L. infantum JPCM5 located on chromosome 2. Each gene is depicted as an arrow (where direction reflects gene orientation), and the connecting gray segments indicates sequence conservation (nucleotide identity ≥ 90%) between L. infantum and L. major genomic contexts. While SCA1 (blue-colored) appears as a single-copy gene in L. infantum, located between SCGR2 and SCGR1, it appears duplicated in L. major

The species that presented the highest number of orthologs from the SCG/R/L family were L. major Friedlin (14 genes), L. infantum (12 genes), L. donovani HU3 (11 genes), C. fasciculata (10 genes) and Leptomonas pyrrhocoris (7 genes) (Fig. 3). Representatives of L. pyrrhocoris do not perform β(1-3)-galactosyltransferase activity [67], while, in several strains of L. infantum studied by Coelho-Finamore et al. [66], only glucose was present in the side-chain, with up to three residues found. As such, it is possible that the products of these genes could perform the transfer of other carbohydrates. Another interesting point was that the LV39c5 and SD 75.1 strains of L. major did not code the majority of the representatives from the SCG family, even though these strains are closely related to the query used to search for the orthologs (L. major Friedlin). However, L. major SD 75.1 presents low levels of β1,3 galactosyl residues (scGal) in its LPG side chain [13], which helps explain this result. On the other hand, the long chains of scGal [21, 56] present in L. major LV39c5 indicate that this apparent contradiction could be related to the incompleteness of its genome assembly, which comprises 849 scaffolds with total gap length of 404,142 bp (NCBI/Assembly accession no. GCA_000331345.1). The distribution of SCGR1-6 orthologs was broader in comparison to SCG1-7 (Fig. 3), despite the β(1-3)-galactosyltransferase activity in LPG of the former not being experimentally proven, as discussed above. All of these genes cluster together with SCA family members, implicating their possible role in side-chain modifications that remains thus far unelucidated. The family of SCG genes localize in chromosomes 16 and 27 in C. fasciculata and L. pyrrhocoris, respectively, close to members of the SCGR/L and SCA families. The fact that this organization is observed in these more basal species provides evidence that homologs of these genes were scattered throughout various chromosomes during the evolution of Leishmania species.

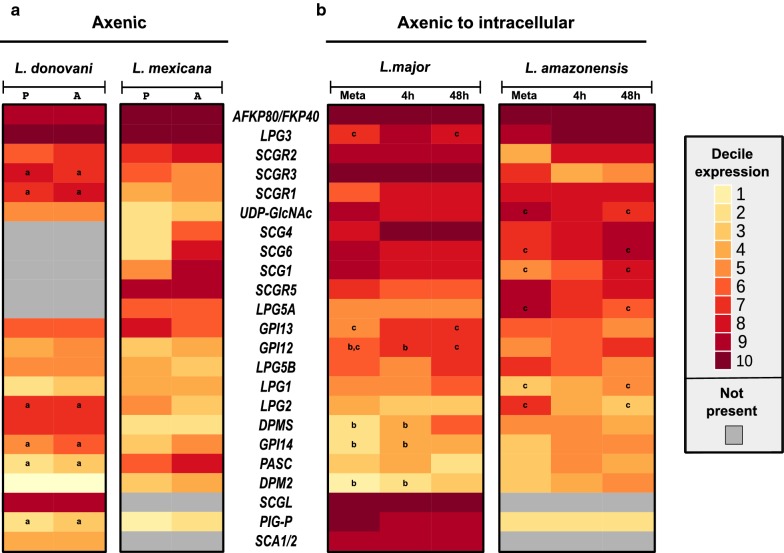

The expression of most, but not all genes that participate in LPG synthesis is constitutive in promastigote and amastigote forms across the four compared Leishmania spp

Once the catalog of Leishmania LPG-related genes was identified, we investigated whether these were de facto expressed, which would support a functional activity. By leveraging the transcriptional profiles available in public databases, we retrieved studies that compared between metacyclic promastigotes and amastigote forms of L. major and L. amazonensis [37], as well as in cultures of promastigote and amastigote L. donovani [35] and L. mexicana [36] (see Additional file 2: Table S2 for more information). We focused on these life stages due to relevance to both parasite-sand fly (promastigote) and parasite-mammal host (amastigote) interactions and, although the axenic form is less biologically meaningful compared to the intracellular forms, it is of importance to study expression of these genes under standard, in vitro growth. Although L. amazonensis was not included in the search for LPG orthologs in our original set of organisms because of poor genome quality (assembled only at the contig-level), we decided to include the RNA-seq data available for this species by mapping its reads against the reference L. mexicana genome.

The expression results were transformed into deciles considering the complete expression set for a given experiment, which unveiled the transcriptional profile of the LPG orthologs (Fig. 6). Similar expression patterns were observed when comparing between life stages or parasite species, indicating that the transcriptional activity of these genes is mostly constitutive. This contrasts with earlier evidence showing that LPG was predominantly expressed in promastigote forms [12]. An explanation for this is that these genes, especially those coding for transferase activities (e.g. LPG2, LPG3, LPG5), also participate in pathways that lead to the synthesis, by amastigote forms, of other membrane compounds, such as PPGs, GIPLs and PGs [68]. On the other hand, initial microarray methods have characterized gene expression in Leishmania as mostly constitutive [69], while recent evidence from RNA-seq studies has pinpointed more marked differences between these life stages [36, 70, 71].

Fig. 6.

Reanalysis of expression data for genes involved in LPG synthesis in four Leishmania species. The expression of LPG genes across four Leishmania species (L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, L. donovani and L. major) are shown, with each cell representing the expression of a gene (discretized into deciles of cpm values) in a given parasite stage. a Axenic cultures of L. donovani and L. mexicana in promastigote (P) and amastigote (A) forms. b Forms of L. major and L. amazonensis at different life forms/timepoints during the transition of metacyclic promastigotes to intracellular amastigotes at 4 h and 48 h post-infection of macrophages. Genes absent in at least two species are not shown. Differences in expression across stages within each species were evaluated using non-parametric tests (see “Methods”), with lowercase letters indicating significant differences (P < 0.05) in the expression of the genes within samples

Of note, a high-expression cluster formed by AFKP80/FKP40 and LPG3 genes (between the 8th and 10th decile) was found in all four species (Fig. 6), indicating a relevant role for the encoded proteins regardless of parasite life stage. High expression levels of the SCG/R/L family genes coding for galactosyltransferases were found in L. major and L. amazonensis, presenting evidence for their coordinated expression. The genes from this family in the same genomic neighborhood (i.e. SCGRs, SCGL, and SCAs) also presented similar expression patterns, which could be related to the polycistronic transcription characteristic of trypanosomatids [72]. The LPG-related genes identified in our genomic data mining approach were found to be expressed across various Leishmania species and life stages, in both axenic culture and intracellularly, supporting our genome mining efforts that indicate that the identified orthologs play corresponding biological roles in these parasites.

Conclusions

Here we present an extensive genomic data mining effort with regard to the repertoire of lipophosphoglycan-related genes in a select group of trypanosomatids. The multiple gene gain/loss events identified during our analysis help to explain some of the observed intra- and interspecies variation of LPG structure. The diversity of LPG has been the focus of many experimental studies in recent years, especially given its importance in host-pathogen and vector-parasite interactions, as well as the vaccine candidate potential of some of the proteins that participate in LPG synthesis. As no previous effort to systematically summarize and evaluate the distribution and relatedness of LPG genes in these organisms has been attempted, our findings contribute towards this objective by allowing a more comprehensive view of the genomic aspects related to the synthesis of LPG.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Metadata of the genomes included in the study.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Metadata of the RNA-seq gene expression studies re-analyzed in the work.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Metadata about the genes chosen as query in orthologous searches.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Information on re-annotated genes and newly predicted open reading frames.

Additional file 5: Table S5. Orthologs genes information (ID, protein products, organism, corresponding open reading frames coordinates and strand).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Leonardo Paiva Farias for critically reading a first draft of this manuscript, and we gratefully acknowledge Andris K. Walter for English language revision and manuscript copyediting assistance.

Abbreviations

- CL

cutaneous leishmaniasis

- d-Arap

d-Arabinopyranose

- GIPLs

glycosylinositolphospholipids

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- LAG

lipoarabinogalactan

- LPG

lipophosphoglycan

- ML

mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

- NSTs

nucleotide-sugar transporters

- PG

phosphoglycan repeat

- PPG

proteophosphoglycan

- scGal

galactosyl residues

- VL

visceral leishmaniasis

Authors’ contributions

PIPR conceived the study and supervised the project. LGA performed data mining, analysis, and curation of the results. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted by LGA and ATLQ. The manuscript was written by LGA and PIPR. LGA, PIPR, LAS, ATLQ and AB interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for scientific content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

LGA was supported by a scholarship from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (Iniciação Científica FAPESB, process number 3645/2018) and is a current recipient of a Master’s scholarship from FAPESB (process number BOL0159/2019). LAS was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, process number 152107/2018-5). ATLQ acknowledges funding from Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (INOVA - process VPPIS-001-FIO-18-45). The study was supported in part by an intramural grant from the Instituto Gonçalo Moniz awarded to PIPR.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The data used in this study are all available from public databases (TriTrypDB (http://www.tritrypdb.org), NCBI/SRA (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), NCBI/Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo)) and the relevant sequence accessions used to perform the analyses described in this manuscript are listed in the main text and the accompanying supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lucas Gentil Azevedo, Email: lucasazevedo18116@gmail.com.

Artur Trancoso Lopo de Queiroz, Email: artur.queiroz@fiocruz.br.

Aldina Barral, Email: aldina.barral@fiocruz.br.

Luciane Amorim Santos, Email: luciane.tika@gmail.com.

Pablo Ivan Pereira Ramos, Email: pablo.ramos@fiocruz.br.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13071-020-3914-9.

References

- 1.Dostálová A, Volf P. Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite-vector interactions overview. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:276. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milon G. Perpetuation of Leishmania: some novel insight into elegant developmental programs. Vet Res. 2009;40:38. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2009021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossage SM, Rogers ME, Bates PA. Two separate growth phases during the development of Leishmania in sand flies: implications for understanding the life cycle. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacks D, Noben-Trauth N. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to Leishmania major in mice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nri933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates PA. Transmission of Leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan American Health Organization. Leishmaniasis: epidemiological report in the americas. 2019. http://www.paho.org/leishmaniasis. Accessed 1 Nov 2019.

- 7.Tiuman TS, Santos AO, Ueda-Nakamura T, Filho BPD, Nakamura CV. Recent advances in leishmaniasis treatment. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e525–e532. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra JA, Prestes SR, Silveira H, Coelho LI, Gama P, Moura A, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scorza BM, Carvalho EM, Wilson ME. Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1296. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desjardins M, Descoteaux A. Inhibition of phagolysosomal biogenesis by the Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2061–2068. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson DE, Kamhawi S, Lawyer P, Turco SJ, Beverley SM, Sacks DL. Leishmania major survival in selective Phlebotomus papatasi sand fly vector requires a specific SCG-encoded lipophosphoglycan galactosylation pattern. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001185. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodge R, Descoteaux A. Phagocytosis of Leishmania donovani amastigotes is Rac1 dependent and occurs in the absence of NADPH oxidase activation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2735–2744. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McConville MJ, Ralton JE. Developmentally regulated changes in the cell surface architecture of Leishmania parasites. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;99:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turco SJ, Descoteaux A. The lipophosphoglycan of Leishmania parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Descoteaux A, Turco SJ. Functional aspects of the Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan during macrophage infection. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:975–981. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang K, Barron T, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. The LPG1 gene family of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;136:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaur U, Showalter M, Hickerson S, Dalvi R, Turco SJ, Wilson ME, et al. Leishmania donovani lacking the Golgi GDP-Man transporter LPG2 exhibit attenuated virulence in mammalian hosts. Exp Parasitol. 2009;122:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Descoteaux A. Leishmania LPG3 encodes a GRP94 homolog required for phosphoglycan synthesis implicated in parasite virulence but not viability. EMBO J. 2002;21:4458–4469. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capul AA, Barron T, Dobson DE, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Two functionally divergent UDP-Gal nucleotide sugar transporters participate in phosphoglycan synthesis in Leishmania major. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14006–14017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610869200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aslett M, Aurrecoechea C, Berriman M, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Carrington M, et al. TriTrypDB: a functional genomic resource for the Trypanosomatidae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D457–D462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roditi I, Liniger M. Dressed for success: the surface coats of insect-borne protozoan parasites. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:128–134. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobson DE, Scholtes LD, Myler PJ, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Genomic organization and expression of the expanded SCG/L/R gene family of Leishmania major: internal clusters and telomeric localization of SCGs mediating species-specific LPG modifications. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;146:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darling ACE, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okonechnikov K, Golosova O, Fursov M, UGENE team Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A. Tree-Puzzle: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:502–504. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldman-Pinkovich A, Balno C, Strasser R, Zeituni-Molad M, Bendelak K, Rentsch D, et al. An arginine deprivation response pathway is induced in Leishmania during macrophage invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005494. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiebig M, Kelly S, Gluenz E. Comparative life cycle transcriptomics revises Leishmania mexicana genome annotation and links a chromosome duplication with parasitism of vertebrates. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005186. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandes MC, Dillon LAL, Belew AT, Bravo HC, Mosser DM, El-Sayed NM. Dual transcriptome profiling of Leishmania-infected human macrophages reveals distinct reprogramming signatures. MBio. 2016;7:e00027. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00027-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

- 39.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ibraim IC, de Assis RR, Pessoa NL, Campos MA, Melo MN, Turco SJ, et al. Two biochemically distinct lipophosphoglycans from Leishmania braziliensis and Leishmania infantum trigger different innate immune responses in murine macrophages. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yadav U, Khan MA. Targeting the GPI biosynthetic pathway. Pathog Glob Health. 2018;112:115–122. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2018.1442764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guha-Niyogi A, Sullivan DR, Turco SJ. Glycoconjugate structures of parasitic protozoa. Glycobiology. 2001;11:45R–59R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.4.45R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraeva N, Butenko A, Hlaváčová J, Kostygov A, Myškova J, Grybchuk D, et al. Leptomonas seymouri: adaptations to the dixenous life cycle analyzed by genome sequencing, transcriptome profiling and co-infection with Leishmania donovani. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005127. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks DL, Modi G, Rowton E, Spath G, Epstein L, Turco SJ, et al. The role of phosphoglycans in Leishmania-sand fly interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:406–411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lázaro-Souza M, Matte C, Lima JB, Arango Duque G, Quintela-Carvalho G, de Carvalho Vivarini Á, et al. Leishmania infantum lipophosphoglycan-deficient mutants: a tool to study host cell-parasite interplay. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:626. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harkins KM, Schwartz RS, Cartwright RA, Stone AC. Phylogenomic reconstruction supports supercontinent origins for Leishmania. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;38:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamhawi S, Ramalho-Ortigao M, Pham VM, Kumar S, Lawyer PG, Turco SJ, et al. A role for insect galectins in parasite survival. Cell. 2004;119:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Handford M, Rodriguez-Furlán C, Orellana A. Nucleotide-sugar transporters: structure, function and roles in vivo. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:1149–1158. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Descoteaux A, Luo Y, Turco S, Beverley S. A specialized pathway affecting virulence glycoconjugates of Leishmania. Science. 1995;269:1869–1872. doi: 10.1126/science.7569927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fuente S, Peiró-Pastor R, Rastrojo A, Moreno J, Carrasco-Ramiro F, Requena JM, et al. Resequencing of the Leishmania infantum (strain JPCM5) genome and de novo assembly into 36 contigs. Sci Rep. 2017;7:18050. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18374-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jesus-Santos FH, Lobo-Silva J, Ramos PIP, Descoteaux A, Lima JB, Borges VM, et al. LPG2 gene duplication in Leishmania infantum: a case for CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing (submitted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Iantorno SA, Durrant C, Khan A, Sanders MJ, Beverley SM, Warren WC, et al. Gene expression in Leishmania is regulated predominantly by gene dosage. MBio. 2017;8:e01393. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01393-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dobson DE, Mengeling BJ, Cilmi S, Hickerson S, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Identification of genes encoding arabinosyltransferases (SCA) mediating developmental modifications of lipophosphoglycan required for sand fly transmission of Leishmania major. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28840–28848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sacks DL, Brodin TN, Turco SJ. Developmental modification of the lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania major promastigotes during metacyclogenesis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;42:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90165-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pimenta P, Turco S, McConville M, Lawyer P, Perkins P, Sacks D. Stage-specific adhesion of Leishmania promastigotes to the sandfly midgut. Science. 1992;256:1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.1615326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guo H, Novozhilova NM, Bandini G, Turco SJ, Ferguson MAJ, Beverley SM. Genetic metabolic complementation establishes a requirement for GDP-fucose in Leishmania. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:10696–10708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.778480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Werneck GL. Visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: rationale and concerns related to reservoir control. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014;48:851–856. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ribeiro VM, da Silva SM, Menz I, Tabanez P, Nogueira FDS, Werkhaüser M, et al. Control of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: recommendations from Brasileish. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martins-Melo FR, Lima M, Ramos AN, Alencar CH, Heukelbach J. Mortality and case fatality due to visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: a nationwide analysis of epidemiology, trends and spatial patterns. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider P, Treumann A, Milne KG, McConville MJ, Zitzmann N, Ferguson MA. Structural studies on a lipoarabinogalactan of Crithidia fasciculata. Biochem J. 1996;313:963–971. doi: 10.1042/bj3130963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alcolea PJ, Alonso A, García-Tabares F, Toraño A, Larraga V. An insight into the proteome of Crithidia fasciculata choanomastigotes as a comparative approach to axenic growth, peanut lectin agglutination and differentiation of Leishmania spp. promastigotes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soares RPP, Macedo ME, Ropert C, Gontijo NF, Almeida IC, Gazzinelli RT, et al. Leishmania chagasi: lipophosphoglycan characterization and binding to the midgut of the sand fly vector Lutzomyia longipalpis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;121:213–224. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coelho-Finamore JM, Freitas VC, Assis RR, Melo MN, Novozhilova N, Secundino NF, et al. Leishmania infantum: lipophosphoglycan intraspecific variation and interaction with vertebrate and invertebrate hosts. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butenko A, da Silva Vieira T, Frolov AO, Opperdoes FR, Soares RP, Kostygov AY, et al. Leptomonas pyrrhocoris: genomic insight into parasite’s physiology. Curr Genomics. 2018;19:150–156. doi: 10.2174/1389202918666170815143331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Svárovská A, Ant TH, Seblová V, Jecná L, Beverley SM, Volf P. Leishmania major glycosylation mutants require phosphoglycans (lpg2−) but not lipophosphoglycan (lpg1−) for survival in permissive sand fly vectors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leifso K, Cohen-Freue G, Dogra N, Murray A, McMaster WR. Genomic and proteomic expression analysis of Leishmania promastigote and amastigote life stages: the Leishmania genome is constitutively expressed. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;152:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruy PDC, Monteiro-Teles NM, Miserani Magalhães RD, Freitas-Castro F, Dias L, Aquino Defina TP, et al. Comparative transcriptomics in Leishmania braziliensis: disclosing differential gene expression of coding and putative noncoding RNAs across developmental stages. RNA Biol. 2019;16:639–660. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2019.1574161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patino LH, Ramírez JD. RNA-seq in kinetoplastids: a powerful tool for the understanding of the biology and host-pathogen interactions. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;49:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Gaudenzi JG, Noé G, Campo VA, Frasch AC, Cassola A. Gene expression regulation in trypanosomatids. Essays Biochem. 2011;51:31–46. doi: 10.1042/bse0510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arcà B, Lombardo F, Struchiner CJ, Ribeiro JMC. Anopheline salivary protein genes and gene families: an evolutionary overview after the whole genome sequence of sixteen Anopheles species. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:153. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3579-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akhoundi M, Kuhls K, Cannet A, Votýpka J, Marty P, Delaunay P, et al. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of Leishmania parasites and sandflies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Metadata of the genomes included in the study.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Metadata of the RNA-seq gene expression studies re-analyzed in the work.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Metadata about the genes chosen as query in orthologous searches.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Information on re-annotated genes and newly predicted open reading frames.

Additional file 5: Table S5. Orthologs genes information (ID, protein products, organism, corresponding open reading frames coordinates and strand).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The data used in this study are all available from public databases (TriTrypDB (http://www.tritrypdb.org), NCBI/SRA (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), NCBI/Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo)) and the relevant sequence accessions used to perform the analyses described in this manuscript are listed in the main text and the accompanying supplementary materials.