Abstract

Despite the critical role behavioral health care payers can play in incentivizing the use of evidence-based practices (EBPs), little research examines which incentives are used in public mental health systems, the largest providers of mental health care in the United States. We surveyed state mental health directors from 44 states about whether they employ any of seven strategies to increase the use of EBPs. Participants also ranked attributes of each incentive based on diffusion of innovation theory (relative advantage, simplicity, compatibility, observability and trialability) and perceived effectiveness. Almost three-quarters of state directors endorsed using at least one financial incentive; most paid for training and technical assistance. Few used other incentives. Strategies perceived as simple and compatible were more readily adopted. Enhanced rates and paying for outcomes were perceived as most effective, yet least deployed, suggesting that simplicity and organizational compatibility may be the most decisive factors in choosing incentives.

Many public behavioral health systems are actively trying to increase the availability of evidence-based practices (EBPs) for the people they serve. A rapidly expanding list of state and county systems encourage agencies to use EBPs by offering them incentives or instituting mandates. Free training and technical assistance are often provided as well (1,2). Despite this momentum and intensifying consensus that EBPs are critical to providing quality care, they still are infrequently used (3,4). One explanation for this enduring research-practice gap is that the policies used to encourage the implementation of EBPs are themselves not effective (5).

Financing and establishing regulatory policy is an important driver of EBP use in almost every published conceptual framework of factors affecting implementation (6). Raghavan and colleagues suggest that payers have at their disposal the following policy mechanisms to increase the use of EBPs within agencies: enhanced reimbursement strategies for the use of EBPs, training providers and consumers in EBPs, publicly recognizing high-performing agencies, reducing regulatory burden, giving agencies that use EBPs advantages in competitive bidding processes (fast-tracking), and directing patient traffic towards agencies using EBPs (5). In 2003, the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health urged the public sector to provide financial incentives to increase the use of EBPs (7). Few of the other incentives Raghavan and colleagues describe have been widely promoted. There has been almost no measurement of whether and how incentives are used in practice (8–10).

State behavioral health systems are in a unique and powerful position to promote the use of EBPs. While ultimately we are interested in how financial incentives may promote the use of EBPs, we must first establish the extent to which different incentive strategies are used. The present study gathered information about states’ use of each incentive, and state officials’ perceptions of the characteristics of these incentives. We characterize these incentives as innovations that states choose to adopt or not, and therefore use diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory (11) as a framework. The DOI framework has been used across varied disciplines (e.g., agriculture, medicine, information technology) to understand the adoption of new innovations or practices, and posits five key characteristics of an innovation that influence the decision to adopt: perceived advantage, compatibility with existing procedures, simplicity, gradually implementable, and observable. Perceived advantage is the benefit that the innovation appears to have over current procedures. Compatibility reflects the congruence between the innovation and existing procedures. Simplicity describes how readily alterations in extant procedures could be accommodated. DOI posits that an innovation is more likely to be accepted if it can be gradually implemented in small steps on a trial basis (e.g. trialability), and if the results are observable, or visible to others. Further, these key attributes are critical factors that encourage the adoption of any innovation - in this case, innovations to promote EBP. In his synthesis of diffusion studies, Rogers (2005) suggests that perceived advantage, simplicity, and compatibility are key factors that explain adoption decisions, whereas observability and trialability are not as consistently important. We therefore hypothesized that incentives that hold relative advantage, and are simple and compatible would be more likely to be implemented.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We partnered with the largest organization of state mental health directors, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD), to distribute a brief survey. We sent an e-mail inviting directors (or their designated proxies) to complete a survey on incentives and evidence-based practices. Several reminders were sent. Data were collected from representatives of 44 states (response rate = 88%) representing 90% of the population (12). Data were collected between October 2016 and April 2017. All procedures were approved by the REMOVED FOR BLINDING Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Our survey instrument comprised 21 items. Efforts were made towards parsimony to enhance the response rate. Respondents were queried on the use of 7 different innovations described by Raghavan and colleagues, and the probability that each incentive would be implemented in the future to promote the use of evidence based practices. Respondents were asked to endorse whether each incentive met criteria for each of the five DOI characteristics (i.e., perceived advantage, compatible with existing procedures, simplicity, gradually implementable, observable). Finally, respondents were asked to endorse (on a 5-point scale) how effective each incentive would be in promoting adoption of EBPs, if the barriers to these incentives were removed. The survey was developed and field tested with the consultation of an advisory board of stakeholders with administrative and research experience in public mental health systems.

Statistical Analysis

For each incentive, percentages were calculated for state utilization, endorsement on each of the 5 DOI attributes, and perception of perceived effectiveness (N=44, see Table 1). The association between these summary statistics (N=7) was then examined with Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients to assess the relationships between endorsement of each DOI key attribute and incentive usage.

Table 1.

State utilization of incentives and endorsement on Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) characteristics and perceived effectiveness

| Incentive Type | % Implement (N = 44) | DOI Characteristics Endorsed (N = 44) | How effective would incentive be if it were easily implementeda (N = 44) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better than what we are doing now to promote EBP | Compatible with existing procedures and infrastructure | Simple to Implement | Gradually implemented in small steps, or on a trial basis | Effects immediately observable | M | SD | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| Paid for training or technical assistance | 61 | 14 | 66 | 95 | 18 | 16 | 3.79 | 0.94 |

| Publicly recognized high performing EBP providers | 23 | 27 | 50 | 77 | 27 | 11 | 3.29 | 0.77 |

| Directed patients towards providers who use EBPs | 18 | 16 | 30 | 68 | 20 | 9 | 3.64 | 0.96 |

| Enhanced reimbursement rates | 11 | 41 | 32 | 70 | 50 | 9 | 4.40 | 0.80 |

| Reduced regulatory burden for providers who provide EBP | 9 | 18 | 16 | 36 | 30 | 16 | 3.55 | 0.94 |

| Paid agencies for clinical outcomes | 9 | 34 | 23 | 52 | 52 | 20 | 4.24 | 0.98 |

| Fast-tracked providers using EBPs in the competitive bidding process | 2 | 5 | 16 | 41 | 20 | 2 | 3.24 | 1.23 |

Scale of 1–5 (Not Effective-Very Effective)

Results

State Use of Incentives

Table 1 shows that 71% of states endorsed using at least one incentive to promote the use of EBPs; 61% paid for training and technical assistance. Less than a quarter reported using each of the other strategies: publicly recognizing high performing EBP providers (23%), directing patients towards providers who use EBPs (18%), enhanced reimbursement rates (11%), pay agencies for clinical outcomes (9%), and fast-tracking providers using EBPs in the competitive bidding process (2%). The two incentives rated as most likely to be effective if implemented were enhanced reimbursement rates and paying for outcomes.

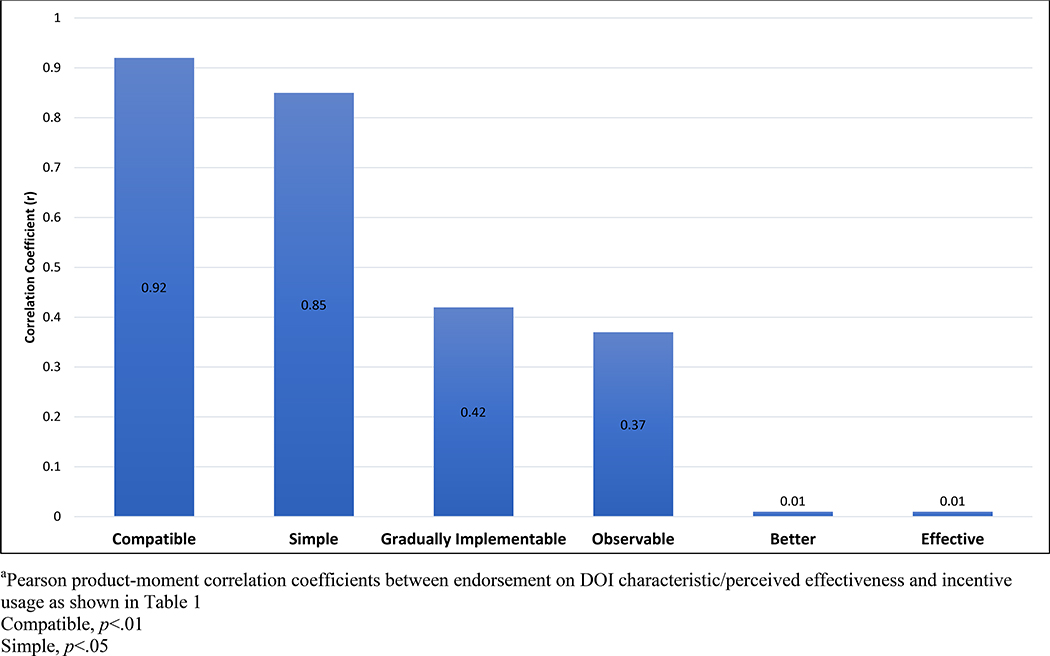

Figure 1 displays the correlation of use of incentives with diffusion of innovation constructs. Perception of the compatibility of the innovation and its use was positively correlated (r = 0.92, p = .003). There was also a positive correlation between simplicity and use (r = .85, p < .017).

Figure 1.

Correlation between Each DOI characteristic, perceived effectiveness and states’ use of incentives (N=7)

Discussion

The majority of expenditures in the behavioral health marketplace are publicly funded (13). State governments, the largest payers in behavioral health, therefore have much at stake in designing and implementing effective incentives to improve care. We found that the most commonly used incentive to increase the use of EBPs is to provide training and technical assistance. Few states do anything else, despite the growing evidence and consensus that training as the primary vehicle of EBP implementation efforts in the public sector is necessary but not sufficient (14,15). Training alone does not lead to change in practice (16,17)

On average, state directors rated training as both compatible and simple to use. On the other hand, it was rated as much less effective and much lower in all other DOI domains than enhanced reimbursement rates and paying for outcomes. In fact, these two were least used strategies. This finding suggests that, of the DOI constructs, simple and compatible may be particularly important in driving the adoption of financial incentives to promote EBPs in public behavioral health systems.

We have two hypotheses about why enhanced reimbursement rates and paying for outcomes are not used, despite their being rated as effective and advantageous. First, of the seven incentives, these two by far require the most measurement. The adoption of enhanced reimbursement rates and paying for outcomes to promote EBPs while simple in concept, is extraordinarily complex in execution, and requires sophisticated data collection and analysis, and payer financial capacity to pay for incentives. (18). While there are many validated measures of symptoms and functioning, there are no definitive and few widely accepted behavioral health outcome measures, such as the presence or absence of disease or mortality. Some have argued that neither incentives, metrics, nor populations have been adequately designed or identified to ensure (and measure) quality improvement through incentives (19–21). Helping states implement enhanced rates and paying for outcomes will first require more research and support to help these systems implement comprehensive and easy-to-use approaches to measuring outcomes.

Second, enhanced rates and paying for outcomes has the potential to create inequity in the public behavioral health care system, with some providers benefiting more than others, which can in turn affect providers’ bottom line, fracture relationships between payers and providers, or even reduce access to care if providers leave the network. Any implementation in a behavioral health care system requires the “delicate dance” of collaboration, coordination, and negotiation among all stakeholders, particularly given rapidly contracting state behavioral health budgets (22,23). Collaborative stakeholder approaches to identifying fair and transparent incentives would be particularly beneficial to this end (24). Future research may include qualitative study might allow for a more detailed assessment of and insight into these challenges while identifying specific barriers that may be common across settings.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge some limitations of this research. First, state mental health directors or their designated proxies may not be fully informed about all state behavioral health initiatives, localized efforts or pilot projects. State leadership turnover amplifies this potential missed information (Hepburn, personal communication). We also recognize that in some states, the county may be a more meaningful unit of analysis in terms of the role of payment, policy and management, and we do not include county-level representation in this study. Additionally, state policies and financing change frequently, particularly in the post-Affordable Care Act era. The findings presented in this article are a snapshot of an evolving process as it appeared in 2016.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the current study contributes new information towards understand the landscape of financial incentives employed by the biggest players in the behavioral health market place to promote EBPs. To our knowledge, this is the first national survey of state-level payers describing the employment of financial incentives to increase the use of EBPs. We found that payers are not employing the incentives they perceive as most effective, and largely only using one strategy due to simplicity and compatibility. Future work should focus on barriers to measurement that likely hinder the adoption and implementation of paying for outcomes and enhanced reimbursement rates, with the ultimate goal of measuring the effectiveness of incentives on EBP implementation efforts.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NIH 1F32MH103960

Footnotes

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Stewart, University of Pennsylvania - Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, 3535 Market Street 3rd Floor, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104.

Steven C. Marcus, University of Pennsylvania - School of Social Policy & Practice, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Trevor R. Hadley, Univ of Pennsylvania - Ctr for Mental Health, 3600 Market St, Rm 717, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Brian Hepburn, St of Md Mtl Hyg Adm, 201 W Preston St, Baltimore, Maryland 21201.

David S. Mandell, Universityof Pennsylvannia Perleman School of Medicine - Department of Psychiatry, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

References

- 1.Hoagwood KE, Olin SS, Horwitz S, et al. : Scaling up evidence-based practices for children and families in New York State: toward evidence-based policies on implementation for state mental health systems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53 43: 145–157, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beidas RS, Stewart RE, Adams DR, et al. : A Multi-Level Examination of Stakeholder Perspectives of Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices in a Large Urban Publicly-Funded Mental Health System. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHugh RK, Barlow DH: The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist. Vol 65(2) 73–84, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruns EJ, Kerns SEU, Pullmann MD, et al. : Research, Data, and Evidence-Based Treatment Use in State Behavioral Health Systems, 2001–2012. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) appips201500014, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghavan R, Bright CL, Shadoin AL: Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implementation science : IS 3: 26, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. : Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science: IS 4: 50, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. DHHS Pub. No. MSA-03–3832. Rockville., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducharme LJ, Abraham AJ: State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 3: 17, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rieckmann TR, Kovas AE, Cassidy EF, et al. : Employing policy and purchasing levers to increase the use of evidence-based practices in community-based substance abuse treatment settings: reports from single state authorities. Evaluation and Program Planning 34: 366–374, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rieckmann TR, Kovas AE, Fussell HE, et al. : Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices for Treatment of Alcohol and Drug Disorders: The Role of the State Authority. The journal of behavioral health services & research 36: 407–419, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers E: Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. Simon & Schuster [Google Scholar]

- 12.State Population Totals Tables: 2010–2016 [Internet] Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/popest/state-total.html

- 13.Mental Health Financing in the United States - A Primer - 8182.pdf [Internet] Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8182.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapp CA, Bond GR, Becker DR, et al. : The role of state mental health authorities in promoting improved client outcomes through evidence-based practice. Community mental health journal 41: 347–363, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, et al. : The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review 30: 448–466, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beidas RS, Kendall PC: Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Vol 17(1) 1–30, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakovshik SG, McManus F, Vazquez-Montes M, et al. : Is supervision necessary? Examining the effects of internet-based CBT training with and without supervision. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 84: 191–199, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart RE, Lareef I, Hadley TR, et al. : Can We Pay for Performance in Behavioral Health Care? Psychiatric Services 68: 109–111, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha AK: Time to Get Serious About Pay for Performance. JAMA 309: 347, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKethan A, Jha AK: Designing Smarter Pay-for-Performance Programs. JAMA 312: 2617, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Acevedo A, et al. : Influencing quality of outpatient SUD care: Implementation of alerts and incentives in Washington State. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 82: 93–101, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honberg R, Kimball A, Diehl S, et al. : State Mental Health Cuts: The Continuing Crisis [White paper] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart RE, Adams DR, Mandell DS, et al. : The Perfect Storm: Collision of the Business of Mental Health and the Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 67: 159–161, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meredith LS, Branstrom RB, Azocar F, et al. : A Collaborative Approach to Identifying Effective Incentives for Mental Health Clinicians to Improve Depression Care in a Large Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organization. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38: 193–202, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]