Abstract

Background

Timed voiding is a fixed time interval toileting assistance program that has been promoted for the management of people with urinary incontinence who cannot participate in independent toileting. For this reason, it is commonly assumed to represent current practice in residential aged care settings.

Objectives

To assess the effects of timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults who cannot participate in independent toileting.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register (searched 2 April 2009), MEDLINE (January 1966 to November 2003), EMBASE (January 1980 to Week 18 2002), CINAHL (January 1982 to February 2001), PsycINFO (January 1972 to August 2002), Biological Abstracts (January 1980 to December 2000), Current Contents (January 1993 to December 2001) and the reference lists of relevant articles. We also contacted experts in the field, searched relevant websites and hand searched journals and conference proceedings.

Selection criteria

We selected all randomised and quasi‐randomised trials that addressed timed voiding in an adult population and that had an alteration in continence status as a primary outcome. We included those trials that had assessed timed voiding delivered either alone or in combination with another intervention and compared it with either usual care, or no timed voiding, or another intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and quality assessment were undertaken by at least two people working independently of each other. Any differences were resolved by discussion until agreement was reached. The relative risk for dichotomous data were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Where data were insufficient to support a quantitative analysis, a narrative overview was undertaken.

Main results

Two trials with a total of 298 participants met the inclusion criteria. Both compared timed voiding plus additional intervention with usual care. In one of these timed voiding was combined with continence products, placement of a bedside commode for each participant, education to staff on transfer techniques, feedback and encouragement to staff, praise to participants for "successful responses" and administration of oxybutynin in small doses. The mean percentage who were incontinent when checked daily was 20% in the intervention group compared with 80% in the control group. No further between group analysis was possible from the data reported. The other trial combined timed voiding with a medical assessment and individualised medical management that was based on clinical data. Reduction in the number of participants with daytime and night‐time incontinence was greater in the intervention group but this difference was statistically significant only for night‐time wetting. There was no difference in the volume of urine lost as determined by pad weighing.

The methodological quality of these trials was not high based on the quality appraisal criteria of the Cochrane Incontinence Group. In particular, there was a lack of clarity regarding levels of blinding. It was not possible to combine data from trials. In both trials, the fixed schedule of toileting was combined with other interventions. The extent to which the results reflect the contribution of timed voiding is unknown because the trials' design did not allow assessment of the effects of the fixed schedule of toileting separately from other components of the interventions.

Authors' conclusions

The data were too few and of insufficient quality to provide empirical support for or against the intervention of timed voiding.

Plain language summary

Timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults

This review examined the use of a fixed interval of voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults. This approach to urinary incontinence is thought to be common in aged care homes for people who require assistance from other people for toileting and continence care. The reviewers found two trials that had evaluated timed voiding. They included 298 elderly women who were living in aged care homes and had reduced cognition and impaired mobility. Reductions in the number of incontinence episodes were reported in each trial. The reviewers found insufficient data for these findings to be combined. Hence, at this point in time, there is not enough evidence on the effects of timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence.

Background

Urinary incontinence commonly affects frail, elderly people. Amongst elderly residents of long‐term care facilities, estimates of the prevalence range between 39% (Palmer 1991) and 50% (Fantl 1991). Cost estimates also vary. Based on a 1994 US study, direct care costs associated with urinary incontinence are thought to be in the range of $11.2 billion annually in the community and $5.2 billion in nursing homes in the USA (Hu 1994). Urinary incontinence is associated with psychological stress and social isolation (Mitteness 1987; Norton 1982; Wyman 1990; Yu 1987), urinary tract infection (Richardson 1995) and pressure sores (Spector 1994). In addition, caregivers of community‐dwelling dementia patients with urinary incontinence report that incontinence management is burdensome (Cassells 2003; Flaherty 1992;) and cite it as an important reason for relinquishing care (Ouslander 1990). Methods of toileting assistance are commonly used in the management of urinary incontinence in the elderly. These include the interventions of prompted voiding, habit retraining and timed voiding (Fantl 1991). This review concentrates on timed voiding. Other Cochrane reviews are available, including those covering prompted voiding (Eustice 2000), habit retraining (Ostaszkiewicz 2004), pelvic‐floor muscle training (Hay‐Smith 2006), bladder training (Wallace 2004) and absorbent products (Fader 2007; Fader 2008).

Timed voiding is sometimes referred to as scheduled, routine or regular toileting. It is characterised by a fixed interval between toileting. It is generally considered a passive toileting assistance program that is initiated and maintained by a caregiver or caregivers and is generally considered appropriate for patients who cannot participate in independent toileting (Fantl 1991). It has been commonly promoted for use in long‐term residential care settings for patients whose incontinence may be associated with cognitive and/or motor deficits (Ouslander 1985). The underlying goal is the avoidance of incontinence episodes rather than restoration of bladder function. The aim is to achieve continence by anticipating involuntary bladder emptying and by providing regular opportunities for elimination to occur.

Whilst acknowledging variability in the definition of timed voiding, this review of timed voiding applied the definitions proposed by Hadley (1986) and by The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, formerly known as the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, AHCPR) (Fantl 1991). In this context, timed voiding is distinguished from bladder training, prompted voiding and habit training.

There is significant overlap between toileting assistance interventions (Cheater 1991). A fixed interval between voids may also be employed in other continence training programs such as bladder training, prompted voiding and habit retraining. The theoretical difference between timed voiding and these other interventions however, lies in the fact that the intervoiding interval in timed voiding remains fixed for the duration of the intervention, whilst the interval may be modified in the other interventions (either lengthening or shortening it). Other differences relate to the absence of patient participation, positive reinforcement, and/or patient education in timed voiding. "Timed voiding does not aim to motivate the patient to delay voiding and resist urge, unlike in bladder training" (Fantl 1991). Furthermore, timed voiding does not attempt to mimic the patient's own individualised toileting pattern, unlike habit retraining.

Objectives

To assess the effects of timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults.

The following hypotheses were addressed.

1. Timed voiding is better than no timed voiding.

2. Timed voiding is better than other interventions.

3. Timed voiding in combination with another intervention is better than that other intervention alone.

4. Timed voiding in combination with another intervention is better than timed voiding alone.

5. Timed voiding in combination with another intervention is better than usual care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi randomised trials of timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence

Types of participants

All adult men and women either with or without cognitive impairment who are diagnosed either by symptom classification or by urodynamic study, as having urinary incontinence.

Types of interventions

Trials wherein at least one group was managed with timed voiding either alone or in combination with other interventions

Types of outcome measures

Patient symptoms

Perception of improvement or cure (as reported by patient or caregiver).

Clinical outcomes

Number of incontinent episodes in 24 hours (as indicated from completed bladder charts, total number and mean).

Pad changes due to incontinence over 24 hours (i.e. as reported by patient or caregiver ‐ total number and mean).

Pad weight.

Voided volume.

Maintenance of skin integrity.

Health status measures

e.g. Short Form 36 (Ware 1993)

Health economic measures

Adherence to research protocol

Other outcomes

Measures of carer assessment (e.g. satisfaction and/or compliance) and non specified outcomes judged relevant when performing the review

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on any of the searches.

Electronic searches

Specialised Register

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Group's Specialised Register of controlled trials which is described under the Incontinence Group's details in The Cochrane Library (For more details please see the ‘Specialized Register’ section of the Group’s module in The Cochrane Library). The register contains trials identified from MEDLINE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and hand searching of journals and conference proceedings. Date of the most recent search of the trials register for this review: 2 April 2009. The trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The terms used to search the Incontinence Group trials register are given below:

({TOPIC.URINE.INCON*}) AND ({DESIGN.CCT*} OR (DESIGN.RCT*}) AND ({INTVENT.PSYCH*})

Key: * = wildcard.

(All searches were of the keywords field of Reference Manager 9.5 N, ISI ResearchSoft).

For this review extra specific searches were performed. These are briefly detailed below, fuller details including the search terms used are given in Appendix 1.

Electronic Databases

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched:

MEDLINE (on OVID) (January 1966 to November 2003). The search was performed on 15 November 2003

EMBASE (on OVID) was searched from 1980 to 2002 Week 18. The search was performed on 9 May 2002

PsycINFO (January 1972 to August 2002). The search was performed in August 2002

CINAHL (January 1982 to February 2001). The search was performed in March 2001

Biological Abstracts (January 1980 to December 2000). The search was performed in March 2001

Current Contents (January 1993 to 2001):

Evidence‐Based databases (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Best Evidence, DARE) (Issue 1, 2001)

Websites

The following websites were searched for relevant studies:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW)

National Health and Medical Research Council (Aust)(NHMRC)

The NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Netting the Evidence (ScHARR)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)

Centre for Evidence‐based Nursing ‐ based at University of York

Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine, Oxford University

World Health Organization (WHO)

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

National Guidelines Clearing House

Searching other resources

Handsearching

The following sources were handsearched for this review:

Journals handsearched for relevant studies.

Evidence‐Based Nursing.

Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing.

Evidence‐Based Medicine.

Journal of Evidence‐Based‐Healthcare Policy and Management.

American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club.

Bandolier.

Effective Health Care.

Effectiveness Matters.

Controlled Clinical Trials.

Journal of Clinical Effectiveness.

Journal of Health Services Research and Policy.

Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice.

Conferences from which proceedings were searched.

The International Continence Society.

British Association of Urological Surgeons.

The Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (USA).

The Continence Foundation of Australia (AUST).

The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (USA).

The Association for Continence Advice (UK).

Contacting experts in the field

Personal contact was made with trialists and other experts in the field.

Reference Lists of Relevant Articles

The reference lists of relevant articles were searched for other possible relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

All abstracts and references identified from the search strategy were checked by two reviewers. All randomised and quasi randomised studies which met the inclusion criteria were selected. These were appraised for methodological quality using the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group's criteria. These criteria are based on the assumption that the avoidance of bias is best achieved by secure concealment of random allocation prior to formal entry; few and identifiable withdrawals and dropouts; and analysis based on an intention to treat. Data from trials that met these inclusion criteria were extracted by two reviewers working independently. Discrepancies were discussed until agreement was reached. Extracted raw data were analysed using the statistical analysis package, Review Manager, developed by The Cochrane Collaboration. The plan was that the relative risk for dichotomous data and weighted mean differences for continuous data would be calculated with 95% confidence intervals, using a fixed effect model, and that where quantitative analysis was impossible or inappropriate, a narrative overview would be undertaken.

Results

Description of studies

The search identified four potential studies that had employed timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults. One of these trials was excluded however because participants were not randomly allocated (Carpenter 1960). Another study was excluded because it used a group cross‐over design without randomisation (Ouslander 1988) (see Table of Characteristics of Excluded Studies). This left two trials that together had 298 participants. One of these involved 20 participants (Smith 1992) and the other 278 participants (Tobin 1986) (see Table of Characteristics of Included Studies).

Most of the participants from the two selected trials were cognitively impaired elderly women (mean age 86.7 years) and all resided in facilities that provided nursing care. Based on a 10‐point mental status questionnaire (Khan 1960), 78.4% of the intervention group and 81.1% of the control group from the trial conducted by Tobin and Brocklehurst (1986) scored lower than 7. Using the Folstein Mini Mental Status Questionnaire (Folstein 1975), the average score for participants involved in the other trial was 7.0 for the intervention group and 8.5 for the control group (maximum total score ‐ 30) (Smith 1992). Both trials reported functional status on the basis of observations of the level of support required for mobility. Fifty‐five percent of the participants in one trial were able to mobilize easily with or without an aid; 25% mobilized with difficulty and 17% were chairfast (Tobin 1986). Six of the 10 intervention group participants and 5 of the 10 control group participants in the other trial, required the support of one person for assistance (Smith 1992). Data were also collected in both trials on the baseline incidence of incontinence and in one trial the volume of incontinence was additionally estimated (Tobin 1986). This involved the collection and weighing of pads.

Both trials reported a baseline assessment which involved a clinical examination and a diagnosis of the type of incontinence. The clinical examination included a rectal examination to exclude faecal impaction, collection of a clean specimen of urine to exclude urinary tract infection, and estimation of post‐void residual volume. One trial additionally included assessment procedures to identify women with vaginal atrophy (Tobin 1986) and found that 21% of 95 female participants had vaginal atrophy. Urodynamic investigations were undertaken in two of the participants in the trial conducted by Tobin and Brocklehurst (1986), whilst bedside cystometry was performed on each participant in the trial conducted by Smith and colleagues (1992). On the basis of these procedures, nearly all participants were diagnosed with detrusor overactivity. In both trials timed voiding was combined with other modalities and was compared with usual care. The approach taken in one trial involved 2 hourly toileting for participants who were assessed as having an unstable bladder. Timed voiding was combined with a medical assessment and an individualised medical intervention. Medical interventions included propantheline and flavoxate for participants with an "unstable bladder" and/or ethinyloestradiol for women with urodynamic stress incontinence combined with pelvic floor muscle training and/or antibiotic therapy for participants with a urinary tract infection. The intervention was delivered by nursing home staff. Participants were reviewed after two months (Tobin 1986). In the other trial, a schedule of set times to provide toileting assistance was developed in consultation with nursing staff, who were also involved in the delivery of the intervention. Participants were toileted five times per day at times that were consistent with other occasions of staff patient interactions. This was combined with the stepped use of continence products, placement of bedside commodes, education to staff on transfer techniques, feedback and encouragement to staff, praise to participants for "successful responses" and administration of oxybutynin in small doses (Smith 1992). This last phase was abandoned after only one week due to side effects and hence, there were no outcome data reported for that time period. The duration of the trial was three and a half months.

Risk of bias in included studies

Potential for bias at trial entry, at time of treatment or outcome assessment

A partially randomised approach to allocation of participants was used in one trial. Whilst some of the participants were randomly allocated, others were purposively selected on the basis of available numbers (Tobin 1986). Data were insufficient to assess the degree of concealment associated with the allocation. Blinding of the intervention was not possible and it was not clear whether or not outcome assessment had been 'blind'.

Smith and colleagues (Smith 1992) described a purposive selection process and group matching based on levels of incontinence. Further consultation with the main investigator of the study however suggested that participants were assigned numbers and that these were picked out of a hat. Whilst the extent to which participants and/or caregivers were blinded to allocation is not reported, education and performance feedback to caregivers were integral components of the intervention. As has been noted in the systematic reviews on bladder training and prompted voiding (Eustice 2000) blinding of participants and/or those involved in the delivery and/or assessment of interventions of this nature is not always possible.

Potential for bias in trial analysis

One trial with a very small sample size provided no data on attrition and the number of participants at outcome was not reported (Smith 1992). The other trial was characterised by a high attrition rate, missing data and a complete case analysis (Tobin 1986). The results therefore reflect a subset of the data, but whether this was because it was impossible to measure the others, is not made explicit. In the absence of an intention to treat analysis, the potential for underestimating or overestimating the effects of the intervention must be considered.

Effects of interventions

1. Timed voiding versus no timed voiding

No trials addressed this comparison

2. Timed voiding versus other other treatments

No trials addressed this comparison

3. Timed voiding combined with another intervention versus that intervention alone

No trials addressed this comparison

4. Timed voiding combined with another intervention versus timed voiding alone

No trials addressed this comparison

5. Timed voiding combined with another intervention versus usual care

Two trials addressed this comparison (Smith 1992; Tobin 1986).

Patient symptoms

No data were reported describing patient symptoms

Clinical outcomes

Number of incontinent episodes

This comparison was addressed by each trial. Comprising a total of 20 participants, between group outcome data reported by Smith and colleagues (Smith 1992) was based on a mean group percentage with a reduction in incontinence calculated from observation of each resident's continence status once a day. The intervention was reportedly associated with fewer wet checks at outcome (20% wet vs 80% wet). Further analysis of these data were limited by the absence of reporting of the standard deviation. Although fewer incontinence episodes were observed between baseline and outcome in the intervention group. These data were not collected for the control group, and hence no between group analysis was possible.

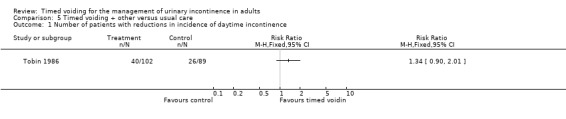

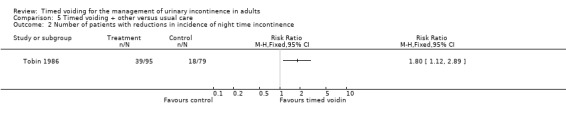

Tobin and Brocklehurst (Tobin 1986) reported a reduction in the number of participants with daytime incontinence in both the intervention and control group. Although this reduction was larger in the intervention group the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (RR 1.34; 95% CI 0.90 to 2.01) A similar pattern of results was seen in respect of night‐time wetting and for this outcome the between group difference was statistically significant (RR 1.80; 95% CI 1.12 to 2.89). This trial was not designed to assess the variable components of the intervention and the extent to which the results reflect timed voiding is unclear.

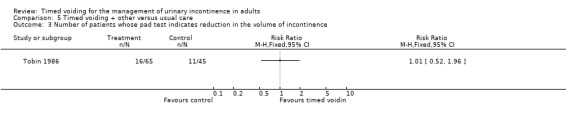

Pad weights

Tobin and Brocklehurst (1986) reported no significant differences in the volume of incontinence as determined by pad weights as a consequence of the intervention, however, the confidence intervals were wide.

Health status measures

No health status data were reported

Health economic measures

Information about the cost implications of the intervention has not been reported

Adherence to the research protocol

Monitoring the capacity of staff to adhere to the research protocol was an integral component of the trial conducted by Smith and colleagues (1992). All personnel involved in the intervention received training and feedback throughout the course of the study. The method by which adherence was calculated was by reference to a form which served the concurrent purpose of recording each participant's continence rate. It is of clinical interest that adherence to research recommendations was reported to be high after staff received training on the technique of transferring participants from bed to commode. This assumes that staff had been previously unaware or unskilled in this technique and suggests that pre‐intervention rates of toileting assistance may have been low. This may have affected the efficacy of the intervention.

Tobin and Brocklehurst (1986) reported a 72% adherence to the research protocol by those participants in the intervention group who were available at outcome. The method by which this was calculated was not reported. It is unclear if the researchers were reporting the adherence of staff to the delivery of the intervention or to the assessment procedures or if they were describing the levels of adherence demonstrated by the participants. Lower levels of adherence by the participants is suggested by the observation that a pad test had to be abandoned in 51 of 161 participants and that one of the reasons cited was the removal of pads by confused residents. Other reasons included faecal incontinence and death or admission to hospital.

Discussion

No trials were identified that addressed the effect of timed voiding alone. It should be noted, however, that there is considerable confusion in the literature over the terms "timed voiding", "habit retraining', "prompted voiding" and "bladder training". The review was based on an a priori definition of timed voiding which was developed after an extensive review of the literature, nevertheless we struggled to categorize the interventions used from the descriptions given. Overlap between interventions was found with some interventions having features of more than one approach. The trial by Smith (Smith 1992) for example, described a fixed schedule of toileting that was combined with the features of staff education and feedback as well as contingent feedback (Smith 1992). The addition of contingent feedback to the fixed schedule raised questions about whether the intervention was therefore consistent with prompted voiding or whether it represented a protocol of timed voiding combined with other features. As the predominant feature was the fixed interval of toileting, we chose the latter interpretation. Conceptual dilemmas such as these highlight the need for a review of current definitions for toileting assistance programs.

Assuming the integrity of current definitions and the differentiation of timed voiding from toileting assistance approaches and/or from bladder training, two trials were identified that met the inclusion criteria. The methodological quality of these trials was not high. In interpreting the results, several issues need to be borne in mind. These include the fact that the sample size was small in one trial (n = 20) (Smith 1992), that both trials were characterised by ambiguity regarding the randomisation process, that blinding associated with allocation, intervention and outcome assessment was unclear and that there were missing data and an absence of intention to treat analyses. These issues raise the possibility that the findings were an overestimation or underestimation.

Timed voiding was identified as just one of a number of strategies in the intervention groups described in the selected trials. It was not possible to conduct sensitivity analyses to evaluate the effect of each of these strategies, hence the extent to which the results reflect the contribution of timed voiding is unknown. It is possible for example that the results obtained in the trial conducted by Smith and colleagues (1992), could reflect the education provided to staff on the technique of transferring participants from bed to bedside commode. Similarly, as participants of the trial conducted by Tobin and Brocklehurst (Tobin 1986) were exposed to a medical assessment and to variable forms of medical treatment in addition to a two‐hourly toileting regimen, the extent to which the two‐hourly toileting contributed to the outcomes is unknown.

In interpreting the results of this review, a number of further limitations should be considered. Cognizant of a previous systematic review having been undertaken on prompted voiding (Eustice 2000), this review applied a narrow interpretation to the concept of timed voiding. Hence, the retrieval and selection of trials reflected this interpretation. Furthermore, as with any review, the quality of the data is determined by the quality of the trials that contribute to it. As noted in the critique of the quality of included trials, the reports were characterised by missing or incomplete data and efforts to contact authors to obtain clarification or further data were only partially successful. This review was primarily drawn from publications in English‐speaking language journals although one major database of non‐English speaking language journals was searched. This yielded one potentially relevant publication (Kunikata 1993). This was subsequently translated, reviewed and relegated to the Table of Excluded Studies. Whilst the search was designed to be as comprehensive and inclusive as possible, nevertheless the potential exists for studies to have been overlooked by virtue of publication bias.

Bearing in mind these limitations, data were insufficient to enable a quantitative estimate of treatment effect and the number of trials was insufficient to examine the effect of differing levels of quality on outcomes. The data were too few and of insufficient quality to provide empirical support for the intervention of timed voiding.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in an adult population.

Implications for research.

This review makes explicit the gaps in research on toileting assistance programs and confirms observations of a high level of confusion over definitions. The point of differentiation between timed voiding and prompted voiding in particular is ambiguous. There is a critical need for a review of current definitions and of the theoretical assumptions that underpin toileting assistance programs.

Assuming that timed voiding and other toileting assistance programs are mutually exclusive however, there is a need for more comparative studies which use explicit methods of reporting, which recruit larger sample sizes and which aim to minimize bias. These should address the intervention as it applies to variable populations and settings and with variable types of incontinence. Predictors of response need to be identified as does a set of criteria that enables discrimination between those individuals who would best respond to timed voiding from those whose incontinence is best addressed with other approaches, including checking and changing procedures. Finally, further research on toileting assistance programs such as timed voiding should identify the optimal method of delivery and include the range of outcomes sought in this review.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2000 Review first published: Issue 1, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 February 2007 | New search has been performed | Second update Issue 3, 2007 ‐ an updated search for potentially relevant trials was undertaken ‐ no new trial reports were found. The existing synopsis was replaced by a Plain Language Summary in accordance with Cochrane guidelines. |

| 1 April 2005 | New search has been performed | minor update: one study excluded (Schnelle 2002) |

| 26 November 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge foremost the contribution of colleagues, Karen Quinn, Susan Hunt, Keren Day, Leigh Pretty, Michelle Macvean and Phil Maude in relation to the data extraction and critical appraisal phase of the review. Our thanks also to all members of the Editorial team in the Incontinence Review Group who have been extremely patient and supportive. Particular thanks to June Cody, Sheila Wallace and Cathryn Glazener for their generous hospitality and to Peter Herbison for statistical support. We also thank the Australasian Cochrane Centre for their involvement in progressing the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods and terms used for this specific review

Electronic Databases The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched:

Search strategy for MEDLINE (on OVID) (January 1966 to November 2003). The search was performed on 15 November 2003 using the following search terms: 1 exp behavior therapy 2 (behav$ adj25 therapy).mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 3 exp cognitive therapy/ 4 (cognit$ adj25 therapy).mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 5 (conservat$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 6 toilet training.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 7 (habit training or habit retraining).mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading 8 timed void$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 9 prompted void$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 10 (nursing homes and urinary incontinence).mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 11 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 12 exp Urinary Incontinence/ or urinary incontinence.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 13 11 and 12 14 13 not child.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 15 exp randomized controlled trials/ 16 randomized controlled trial.pt. 17 exp random allocation/ 18 exp double blind method/ 19 exp single blind method/ 20 exp clinical trials/ 21 clinical trial.pt. 22 (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 23 ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 24 placebo$.ti,ab. (62844) 25 random$.ti,ab. 26 research design/ 27 placebos.mp. [mp=title, abstract, registry number word, mesh subject heading] 28 or/15‐27 29 14 and 28

Search strategy for EMBASE (on OVID) was searched from 1980 to 2002 Week 18. The search was performed on 9 May 2002 using the following search terms: 1 Randomized Controlled Trial/ 2 controlled study/ 3 clinical study/ 4 major clinical study/ 5 prospective study/ 6 meta analysis/ 7 exp clinical trial/ 8 randomization/ 9 crossover procedure/ or double blind procedure/ or parallel design/ or single blind procedure/ 10 Placebo/ 11 latin square design/ 12 exp comparative study/ 13 follow up/ 14 pilot study/ 15 family study/ or feasibility study/ or pilot study/ or study/ 16 placebo$.tw. 17 random$.tw. 18 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 19 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 20 factorial.tw. 21 crossover.tw. 22 latin square.tw. 23 (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 24 or/1‐23 25 (nonhuman not human).sh. 26 24 not 25 27 behavior modification/ or behavior therapy/ 28 (conservat$ adj25 (intervention$ or therap$)).tw. 29 conservative treatment/ 30 (behav$ adj25 (therap$ or train$ or treatment$ or intervention$)).tw. 31 (habit adj2 (train$ or retrain$)).tw. 32 (void$ adj2 (time$ or prompt$ or schedul$)).tw. 33 toilet$.tw. 34 or/27‐33 35 bladder disease/ or bladder dysfunction/ or detrusor dyssynergia/ or neurogenic bladder/ 36 (continen$ or incontinen$).tw. 37 exp Incontinence/ 38 37 or 35 or 36 39 26 and 34 and 38 40 limit 39 to (embryo <first trimester> or infant <to one year> or child <unspecified age> or preschool child <1 to 6 years> or school child <7 to 12 years> or adolescent <13 to 17 years>) 41 limit 39 to (adult <18 to 64 years> or aged <65+ years>) 42 40 not 41 43 39 not 42

Search strategy for PsycINFO (January 1972 to August 2002). The search was performed in August 2002 using the following search terms: 1 urinary incontinence 2 Behavio* 3 1 and 2

Search strategy for CINAHL (January 1982 to February 2001). The search was performed in March 2001 using the following search terms: 1 behavio?r$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 2 (behav$ adj25 therapy).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 3 cognitive therapy.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 4 (cognit$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 5 (conservat$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 6 (timed void$ or schedule$ void$).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 7 (habit retraining or habit training).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 8 toilet training.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 9 (nurs$ adj25 care).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 10 nurs$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 11 nurs$ home$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 12 dementia$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 13 or/1‐12 14 urinary incontinence or Urinary Incontinence).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 15 13 and 14 16 random$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 17 randomized controlled trial$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 18 random allocation$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 19 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (blind$ or mask$)).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 20 placebo$ control$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation] 21 or/16‐20 22 15 and 21 23 22 not child$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject heading, abstract, instrumentation]

Search strategy for Biological Abstracts (January 1980 to December 2000). The search was performed in March 2001 using the following search terms: 1 behavio?r$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 2 (behav$ adj25 therapy).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 3 cognitive therapy.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 4 (cognit$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 5 (conservat$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 6 (timed void$ or schedule$ void$).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 7 (habit training or habit retraining).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 8 toilet training.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 9 (nurs$ adj care).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 10 nurs$ home$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 11 nurs$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 12 dementia$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 13 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14 (urinary incontinence or Urinary Incontinence).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 15 13 and 14 16 random$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 17 randomized controlled trial$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 18 random allocation$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 19 (clin$ adj25 trial$).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 20 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl) adj (blind$ or mask$)).mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 21 placebo$ control$.mp. [mp=title, keywords, heading words, registry words, abstract, biosystematic codes/super taxa, book title, original language book title, subject headings] 22 or/16‐21 23 15 and 22

Search strategy for Current Contents (January 1993 to 2001): 1 behavio?r$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 2 (behav$ adj25 therapy).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 3 cognitive therapy.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 4 cognitive therapy.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 5 (cognit$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 6 (conservat$ adj25 intervention$).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 7 (timed void$ or schedule$ void$).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 8 (habit retraining or habit training).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 9 toilet training.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 10 (nurs$ adj25 care).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 11 nurs$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 12 nurs$ home$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 13 dementia$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 14 or/1‐13 15 (urinary incontinence or Urinary Incontinence).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author words, keywords plus] 16 14 and 15 17 random$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] (188244) 18 randomized controlled trial$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 19 random allocation$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 20 (clin$ adj25 trial$).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 21 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (blind$ or mask$)).mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 22 placebo$ control$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus] 23 or/17‐22 24 not child$.mp. [mp=abstract, title, author keywords, keywords plus]

Search strategy for Evidence‐Based databases (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Best Evidence, DARE) (Issue 1, 2001) 1. (urinary incontinence not child).mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] Search for: from 1 [urinary incontinence.mp. [mp=title, short title, abstract, full text] urinary incontinence.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct]

Key: $ = wildcard; tw = textword; / = MeSH term or emtree term or other controlled language term with all subheadings; exp = explode; adj25 = within 25 words either side of this word.

Websites The following websites were searched for relevant studies:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW)

National Health and Medical Research Council (Aust)(NHMRC)

The NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Netting the Evidence (ScHARR)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)

Centre for Evidence‐based Nursing ‐ based at University of York

Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine, Oxford University

World Health Organization (WHO)

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

National Guidelines Clearing House

Handsearching The following sources were handsearched for this review:

Journals handsearched for relevant studies.

Evidence‐Based Nursing.

Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing.

Evidence‐Based Medicine.

Journal of Evidence‐Based‐Healthcare Policy and Management.

American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club.

Bandolier.

Effective Health Care.

Effectiveness Matters.

Controlled Clinical Trials.

Journal of Clinical Effectiveness.

Journal of Health Services Research and Policy.

Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice.

Conferences from which proceedings were searched.

The International Continence Society.

British Association of Urological Surgeons.

The Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (USA).

The Continence Foundation of Australia (AUST).

The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (USA).

The Association for Continence Advice (UK).

Contacting experts in the field Personal contact was made with trialists and other experts in the field.

Reference Lists of Relevant Articles The reference lists of relevant articles were searched for other possible relevant trials.

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on any of the searches.

Data and analyses

Comparison 5. Timed voiding + other versus usual care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of patients with reductions in incidence of daytime incontinence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Number of patients with reductions in incidence of night time incontinence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Number of patients whose pad test indicates reduction in the volume of incontinence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Timed voiding + other versus usual care, Outcome 1 Number of patients with reductions in incidence of daytime incontinence.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Timed voiding + other versus usual care, Outcome 2 Number of patients with reductions in incidence of night time incontinence.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Timed voiding + other versus usual care, Outcome 3 Number of patients whose pad test indicates reduction in the volume of incontinence.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Smith 1992.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with unclear allocation concealment. No data on blinding of concealment to outcome assessment. No data on follow‐up. No data on drop‐outs. Outcome data based on between Group data for Group frequency of UI. Outcome data on individual rates of UI based on within group data. | |

| Participants | 20 residents of a skilled nursing section of a "life care community" Mean age 91.3 yrs ‐ "primarily demented and frail elders". | |

| Interventions | 3 & 1/2 mths duration. Gp 1: (10) TV delivered by usual care staff with education, feedback & encouragement from research staff Phase 1: 4 wks usual care & assessment Phase 2: 4 wks A/A + pad/pant + commode + feedback Phase 3: 4 wks A/A + education re transfers + TV 5 times per day with verbal reinforcement Phase 4: 1 wk A/A + oxybutynin (ceased >1wk). Gp 2: (10) usual care. | |

| Outcomes | Group frequency of UI based on a wet/dry check on each resident between 1.30‐2pm daily. Gp 1: (number not reported) ‐ 21% Gp 2: (number not reported) ‐ 85%. Individual rates of UI derived from 24 hr bladder charts. Gp 1: (number not reported) 38% Gp 2: (number not reported) missing data Adherence: 90.6% after adjustment of schedule in phase 3 | |

| Notes | Protocol deviations in relation to education on transfer techniques and adjustment of toileting schedule Unable to evaluate relative contribution of TV. Author contacted for additional information ‐ reported a random allocation approach | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Tobin 1986.

| Methods | Quasi randomised controlled trial. Concealed allocation: not clear Outcome assessment blinded: not stated Adequate follow‐up: no data Drop outs accounted for: yes Between group analysis: yes Intention to treat analysis: no | |

| Participants | 278 residents (48 males, 230 females) from 30 residential homes for the elderly. Majority with chronic brain failure. Mean age 82.2 yrs. 40% impaired mobility. 93% of women & 97% of men had UI due to unstable bladder contractions | |

| Interventions | 2 mths duration. Gp 1: (174) TV for residents with unstable bladder + propanetheline 15mg + flavoxate 200mg QID + pelvic floor muscle exercises for females with genuine stress incontinence + antibiotics for residents with urinary tract infections + ethinyloestradiol 30mg daily for 3/52 females with atrophic vaginitis Gp 2 (104) no advice | |

| Outcomes | Number of residents with improvement in frequency of UI during daytime

Gp 1: (102) 40

Gp 2: (89) 26 Number of residents with improvement in frequency of UI during night Gp 1: (95) 39 Gp 2: (79) 18 Number of patients whose pad test showed improvement Gp 1 (65) 16 Gp 2 (45) 11 Adherence Gp 1: (112) 79% full compliance Gp 2 : no data |

|

| Notes | No data on method of measuring adherence. No data on eligibility. No a priori power calculation. Baseline freq of UI not reported. Method of measuring frequency of UI not reported. Intensity & delivery of TV not reported. Unable to evaluate relative contribution of TV | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Gp = group; UI = urinary incontinence; TV = timed voiding; QID = 4 x day;

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bear 1997 | RCT of 24 older rural women randomised to either behavioural management for continence (BMC) or control. BMC involved self monitoring, a scheduling regimen of either bladder training or prompted voiding and PME with biofeedback. |

| Burgio 1985 | Non RCT ‐ 48 volunteers aged 60 ‐86 yrs who received biofeedback assisted exercises plus relaxation training plus an intervention that was termed 'habit retraining'. Participants were instructed to void 2 hourly for 4‐week baseline period as well as during treatment however those with detrusor motor instability were taught deferrment techniques. Pre and post evaluation. |

| Burgio 1989 | Non RCT ‐ 20 men with persistent post‐prostatectomy incontinence purposively selected for 2 weeks of 2 hourly voiding followed by biofeedback |

| Burgio 1994 | Non RCT ‐ 41 incontinent residents of a skilled nursing care facility who were purposively selected for one of four groups with exposure to varying schedules of prompted voiding |

| Burgio 1998 | RCT ‐ 91 women aged 55‐92 with urge incontinence or mixed symptoms randomised to biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle exercises with bladder training or drug treatment |

| Carpenter 1960 | Non RCT ‐ 94 hospitalised patients with long term psychiatric disorders and urinary or fecal incontinence ‐ purposively allocated to a fixed schedule of toileting with the addition of varying degrees of positive feedback/reward |

| Castleden 1986 | Double‐blind placebo controlled trial of 33 volunteers attending an outpatient continence clinic. Intervention referred to as 'habit retraining' ‐ description is consistent with bladder training |

| Chanfreau‐Rona 1984 | 24 elderly female residents of a psychogeriatric ward purposively allocated to either usual care or to habit retraining combined with environmental modifications, pad and pant system and verbal and material reinforcement |

| Chanfreau‐Rona 1986 | 30 elderly residents of a psychogeriatric ward purposively allocated to either usual care or to habit retraining combined with environmental modifications, pad and pant system and verbal and material reinforcement |

| Colling 1992 | Cluster randomised controlled trial of 113 elderly nursing home residents allocated to 12 weeks of either patterned urge‐response toileting (PURT) or usual care |

| Colling 2002 | RCT of 106 home‐bound dependent elders with or without caregivers allocated to 6 weeks of either patterned urge‐response toileting (PURT) or usual deferred PURT |

| Colombo 1995 | RCT ‐ 81 women with detrusor instability allocated to 6 weeks of either bladder training or medication |

| Engberg 1997 | RCT ‐ 124 homebound older adults ‐ cognitively intact patients received 8 weeks of bladder training with biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle exercises and deferment techniques/cognitively impaired patients received 8 weeks of either prompted voiding or usual care |

| Engberg 2002 | RCT of 29 cognitively impaired and housebound elders randomised to either prompted voiding or delayed prompted voiding |

| Engel 1990 | Non RCT of 62 elderly men and women admitted to a Geriatric Continence Research Unit who received prompted voiding and were then allocated to different forms of feedback from staff |

| Fantl 1991 | RCT ‐ 123 non institutionalised women 55 years or older allocated to 6 weeks of either bladder training or deferred bladder training |

| Fonda 1994 | RCT ‐ 78 community dwelling older adults attending an outpatient continence clinic allocated to either immediate or deferred conservative management |

| Gaitsgori 1998 | Non RCT ‐ 35 demented patients from 2 nursing homes. Pre and post evaluation of an intervention which was referred to as "timed voiding". Description of the intervention is consistent with review definition of habit retraining. Excluded on basis of methodological design |

| Grosicki 1968 | Non RCT ‐ 17 "geriatric" patients of a neuropsychiatric hospital purposively selected for a toileting program based on principles of operant conditioning |

| Hu 1988 | RCT ‐ 133 women with urinary incontinence from 7 nursing homes. Intervention consisted of prompted voiding with hourly checks and prompts, verbal reinforcement, and contingent reinforcement |

| Jarvis 1980 | RCT ‐ 60 women with detrusor instability treated with 'bladder drill'. |

| Jarvis 1981 | RCT ‐ 50 women with detrusor instability treated with in‐patient bladder drill compared to out‐patient drug therapy. |

| Jarvis 1982 | Non RCT of 33 women with primary vesical sensory urgency treated with 'bladder drill'. |

| Jilek 1993 | Non RCT ‐ 28 residents of a nursing home purposively selected for 8 weeks of 2 hourly toileting followed by 8 weeks of 4 hourly toileting. |

| Jirovec 2001 | RCT ‐ 118 community dwelling elders with cognitive impairment allocated to 6 months of either individualised scheduled toileting or social contact |

| King 1980 | Non RCT ‐ 15 women with urinary and/or faecal incontinence ‐ residing in psychogeriatric and long‐stay wards ‐ purposively selected for habit retraining |

| Kirkpatrick 1987 | Non RCT ‐ 6 women with urinary incontinence from an intermediate‐care‐unit of a long‐term care facility ‐ purposively selected for habit retraining |

| Kunikata 1993 | Not an RCT. |

| Lagro‐Janssen 1992 | RCT ‐ 110 women attending their GP for incontinence. Women with stress incontinence allocated to either pelvic floor muscle exercises or deferred treatment. Women with urge incontinence allocated to either bladder training or deferred treatment |

| Lekan‐Rutledge 1992 | Non RCT ‐ 9 nursing home residents with urinary incontinence ‐ pre and post evaluation of prompted voiding |

| McCormick 1990 | Non RCT ‐ 10 women with urinary incontinence attending a Geriatric Continence Research Unit ‐ purposively selected for pre and post evaluation of prompted voiding ‐ enhanced with use of a mechanical lifting machine |

| McCormick 1992 | Non RCT ‐ 11 residents of a long‐term care facility ‐ purposively selected for pre and post evaluation of prompted voiding ‐ enhanced with use of a buzzer which sounds in response to wetness |

| McDowell 1992 | Non RCT ‐ 7 individuals with Alzheimer's dementia and their caregivers in a pilot trial of pre and post evaluation of habit retraining |

| O'Brien 1991 | RCT ‐ 378 adults involved in a prevalence study on urinary incontinence allocated to 4 sessions of pelvic floor muscle exercises and bladder training or deferred treatment delivered by a nurse |

| Ouslander 1988 | Double‐blind placebo controlled trial of 15 aged residents from a long‐term care facility who received 2 weeks of no timed voiding, followed by 2 weeks of timed voiding alone, followed by 2 weeks of timed voiding plus placebo, followed by 2 weeks of timed voiding plus anticholinergic medication. Intervention referred to as 'habit retraining' by trialist |

| Ouslander 1995 | A randomized placebo controlled, double‐blinded dose‐adjusted, crossover trial of oxybutynin with prompted voiding to 75 nursing home residents who had failed a prompted voiding alone program |

| Proctor 1999 | RCT ‐ 120 nursing home residents with behavioural problems allocated to either a behavioural training programme and education or control. Change in continence status was not an outcome |

| Ramsay 1996 | RCT ‐ 74 women with mixed symptoms allocated to either inpatient or outpatient bladder training, physiotherapy, fluid manipulation, dietary advice and general support and advice |

| Saltmarche 1991 | RCT ‐ 40 elderly males from 2 nursing homes allocated to 12 weeks of either habit retraining or control |

| Schnelle 1983 | RCT ‐ 21 residents from two nursing homes, randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. Intervention involved 1 hourly wet/dry checks and prompted toileting and contingent reinforcement |

| Schnelle 1988 | Non RCT ‐ 92 residents from 3 nursing homes purposively selected for pre and post evaluation of cost of hourly wet/dry checks with prompted toileting and contingent reinforcement. 36 participants who were responsive were changed to a 2 hourly protocol |

| Schnelle 1989 | RCT of 126 residents from 6 nursing homes purposively selected but randomly assigned to intervention or delayed intervention groups for hourly wet/dry checks, prompted toileting and contingent reinforcement |

| Schnelle 1990 | Follow‐up study in which 91 responsive individuals out of 126 participants who had been involved in a one hour prompted toileting intervention or delayed intervention were moved to a two hour prompted voiding protocol |

| Schnelle 1991 | A descriptive analysis of the implementation of a set of procedures for a 2 hourly prompted toileting program and a 2 hourly changing schedule ‐ based on 81 purposively selected residents from 4 nursing homes |

| Schnelle 1993 | A descriptive analysis of the 6 month outcomes of 76 out of 198 nursing home residents who were responsive to a two hourly prompted toileting protocol |

| Schnelle 1995 | RCT ‐ 76 nursing home residents allocated to either 2‐hourly prompted voiding or 2‐hourly prompted voiding combined with an exercise program |

| Schnelle 2002 | RCT‐ Scheduled voiding programme combined with other components. Did not report change in incontinence. Primary outcomes were cost, appetite and constipation, functional mobility and skin health outcomes |

| Sogbein 1982 | Non RCT ‐ 161 men in a geriatric hospital who were assigned treatment on the basis of clinical symptoms. Twenty of these were diagnosed with detrusor hyperreflexia and were placed on a 2 hourly voiding protocol for 4 Weeks followed by 4 weeks of Dicyclomine hydrochloride (Bentylol) 20mg t.d.s. for another 4 weeks for those who were incontinent 20% or more of the time. |

| Sowell 1987 | Non RCT ‐ 24 purposively selected nursing home residents (ie had reverted to incontinence following a program of prompted voiding) ‐ allocated to receive 1 of 5 different methods of continence management ‐ either one of two different disposable products, one of two different washable products or a toileting procedure. No data on the nature of the toileting program. Primary outcome was cost difference |

| Spangler 1984 | Non RCT ‐ Multiphase cross‐over study of 16 purposively selected non ambulant nursing home residents matched according to levels of incontinence and dehydration and assigned to either regular receipt of offers of fluid and toileting assistance or random offers |

| Subak 2002 | RCT ‐ 12 nursing home residents allocated to either prompted voiding or control |

| Surdy 1992 | RCT ‐ 12 nursing home residents randomly assigned to either prompted voiding or control |

| Szonyi 1995 | RCT ‐ 57 elderly adults with detrusor instability allocated to either bladder training or medication |

| Wilder 1997 | Case study involving 1 male adult with profound 'mental retardation' ‐ received 30 minute toileting plus contingent reinforcement (i.e. prompted voiding) |

| Wiseman 1991 | RCT ‐ 37 elderly frail adults with detrusor instability allocated to either bladder training with medication or bladder training with placebo |

| Wyman 1997 | RCT ‐ 123 older community‐dwelling women allocated to 6 weeks of either bladder training or control |

| Wyman 1998 | RCT ‐ 204 women with genuine stress incontinence and/or detrusor instability allocated to 12 weeks of bladder training, pelvic floor muscle exercises with biofeedback or combination therapy |

Contributions of authors

The review protocol was written by one reviewer (J. Ostaszkiewicz). Two reviewers (J. Ostaszkiewicz, L. Johnston) independently screened all retrieved publications and selected those which met the inclusion criteria. Data extraction and critical appraisal of selected trials was undertaken by external colleagues working independently of each other. One reviewer (J. Ostaszkiewicz) wrote the review and both co‐reviewers contributed to the writing of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Victorian Centre for Nursing Practice Research, School of Nursing, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

External sources

None, Australia.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Smith 1992 {published data only}

- Smith DA, Newman DK, McDowell BJ, Burgio LD. Reduction of incontinence among elderly in a nursing home setting. In: Funk SG, Tornquist EM, Champagne MT, Wiese RA editor(s). Key Aspects of Elder care: Managing Falls, Incontinence and Cognitive impairement. New York: Springer Publishing Co, 1992:196‐204. [Google Scholar]

Tobin 1986 {published data only}

- Tobin GW, Brocklehurst JC. The management of urinary incontinence in local authority residential homes for the elderly. Age & Ageing 1986;15(5):292‐8. [585] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bear 1997 {published data only}

- Bear M, Dwyer JW, Benveneste D, Jett K, Dougherty M. Home‐based management of urinary incontinence: A pilot study with both frail and independent elders. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, & Continence Nursing 1997;24(3):163‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgio 1985 {published data only}

- Burgio KL, Whitehead WE, Engel BT. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. Bladder‐sphincter biofeedback and toileting skills training. Annals of Internal Medicine 1985;103(4):507‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgio 1989 {published data only}

- Burgio KL, Stutzman RE, Engel BT. Behavioral training for post‐prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Journal of Urology 1989;141:303‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgio 1994 {published data only}

- Burgio KL, McCormick KA, Scheve AS, Engel BT, Hawkins A, Leahy E. The effects of changing prompted voiding schedules in the treatment of incontinence in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1994;42(3):315‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgio 1998 {published data only}

- Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, Hardin JM, McDowell BJ, Dobrowski M, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 1998;280(23):1995‐2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carpenter 1960 {published data only}

- Carpenter HA, Simon R. The effect of several methods of training on long‐term incontinent, behaviorally regressed hospitalised psychiatric patients. Nursing Research 1960;9(1):17‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Castleden 1986 {published data only}

- Castleden CM, Duffin HM, Gulati RS. Double‐blind study of imipramine and placebo for incontinence due to bladder instability. Age and Ageing 1986;15(5):299‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chanfreau‐Rona 1984 {published data only}

- Chanfreau‐Rona D, Bellwood S, Wylie B. Assessment of a behavioural programme to treat incontinent patients in psychogeriatric wards. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1984;23(4):273‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chanfreau‐Rona 1986 {published data only}

- Chanfreau‐Rona D, Wylie B, Bellwood S. Behaviour treatment of daytime incontinence in elderly male and female patients. Behavioural Psychotherapy 1986;14(1):13‐20. [Google Scholar]

Colling 1992 {published data only}

- Colling J, Ouslander J, Hadley BJ, Eische J, Campbell EB. The effects of patterned urge‐response toileting (PURT) on urinary incontinence among nursing home patients. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 1992;40:135‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colling 2002 {unpublished data only}

- Colling J, Owen TR, McMcreedy M, Newman D. The effects of a continence program on frail community dwelling elderly persons. Urologic Nursing 2002;23(2):117‐22, 127‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colombo 1995 {published data only}

- Colombo M, Zanetta G, Scalambrino S, Milani R. Oxybutynin and bladder training in the management of female urinary urge incontinence: A randomised study. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 1995;6:63‐7. [Google Scholar]

Engberg 1997 {published data only}

- Engberg S, McDowell BJ, Donovan N, Brodak I, Weber E. Treatment of urinary incontinence in homebound older adults: Interface between research and practice. Ostomy, Wound Management 1997;43(10):18‐22, 24‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg S, McDowell BJ, Weber E, Brodak I, Donovan N, Engberg R. Assessment and management of urinary incontinence amongst homebound older adults: A clinical trial protocol. Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly 1997;3(2):48‐56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engberg 2002 {published data only}

- Engberg S, Sereika SM, McDowell J, Weber E, Brodak I. Effectiveness of prompted voiding in treating urinary incontinence in cognitively impaired homebound older adults. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing 2002;29(5):252‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engel 1990 {published data only}

- Engel, BT, Burgio LD, McCormick KA, Hawkins AM, Scheve AAS, Leahy E. Behavioral treatment of incontinence in the long‐term care setting. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1990;38:361‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fantl 1991 {published data only}

- Fantl JA, Wyman JF, McClish DK, Harkins SW, Elswick RK, Taylor JR, et al. Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. Journal of the American Medical Association 1991;265(5):609‐13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fonda 1994 {published data only}

- Fonda D, Woodward M, D'Astoli M, Chin WF. The continued success of conservative management for established urinary incontinence in older people. Australian Journal on Ageing 1994;13(1):12‐6. [Google Scholar]

Gaitsgori 1998 {published data only}

- Gaitsgori Y, Gruenwald I, Zatmi S, Michalak R. Individual timed voiding as a long‐term treatment modaility for demented patients in nursing homes. Neurourology and Urodynamics. Wiley‐Liss, The International Continence Society (ICS), 28th Annual Meeting, Jerusalem, Israel, 1998.

Grosicki 1968 {published data only}

- Grosicki JP. Effect of operant conditioning on incontinence in neuropsychiatric geriatic patients. Nursing Research 1968;17:304‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hu 1988 {published data only}

- Hu TW, Igou JF, Kaltreider DL, Yu LC, Rohner TJ, Dennis PJ, et al. A clinical trial of a behavioral therapy to reduce urinary incontinence in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Association 261;18:2656‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu TW, Igou JF, Kaltreider DL, Yu LC, Rohner TJ, Dennis PJ, et al. A clinical trial of a behavioural therapy to reduce urinary incontinence in nursing homes. Neurourology & Urodynamics 1988;7(3):279‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu TW, Igou JF, Kaltreider DL, Yu LY, Rohner TJ, Dennis PJ, et al. Behavioral therapy for urinary incontinence in nursing homes. Advances, Institute for the advancement of health 1989;6(3):11‐14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu TW, Kaltreider DL, Igou JF, Yu LC, Rohner TJ. Cost effectiveness of training incontinent elderly in nursing homes: A randomized clinical trial. Health Services Research 1990;25(3):455‐7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jarvis 1980 {published data only}

- Jarvis GJ, Millar DR. The treatment of incontinence due to detrusor instability by bladder drill. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research 1981;78:341‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, GJ. Controlled trial of bladder drill for detrusor instability. British Medical Journal 1980;281:1322‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jarvis 1981 {published data only}

- Jarvis GJ. A controlled trial of bladder drill and drug therapy in the management of detrusor instability. British Journal of Urology 1981;53(6):565‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jarvis 1982 {published data only}

- Jarvis GJ. The management of urinary incontinence due to primary vesical sensory urgency by bladder drill. British Journal of Urology 1981;54:374‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jilek 1993 {published data only}

- Jilek R. Elderly toileting: is two hourly too often?. Nursing Standard 1993;7(47):25‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jirovec 2001 {published data only}

- Jirovec MM, Templin T. Predicting success using individualised scheduled toileting for memory‐impaired elders at home. Research in Nursing and Health 2001;24(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

King 1980 {published data only}

- King MR. Treatment of incontinence. Nursing Times 1980;June:100‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kirkpatrick 1987 {published data only}

- Kirkpatrick MK, Davis C. A bladder retraining program in a long‐term care facility. Nursing Homes 1987;July/Aug:29‐31. [Google Scholar]

Kunikata 1993 {published data only}

- Kunikata S, Park YC, Kurita T, Hishimoto K, Uchida A, Esa A. Clinical study of the timed voiding schedule for urinary incontinence in demented elders. Acta Urologica Japonica 1993;39(7):625‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lagro‐Janssen 1992 {published data only}

- Lagro‐Janssen ALM, Deyruyne FMJ, Smits AJA, Weel C. The effects of treatment of urinary incontinence in general practice. Family Practice 1992;9(3):284‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lekan‐Rutledge 1992 {published data only}

- Lekan Rutledge D, Hogue CC, Miller J. Prompted voiding in the nursing home: effect of clinical and staff management protocols. The Gerontologist 1992;32:162‐3. [Google Scholar]

McCormick 1990 {published data only}

- McCormick KA, Cella M, Scheve A, Engel BT. Cost‐effectiveness of treating incontinence in severly mobility‐impaired long‐term care residents. Quality Review Bulletin 1990;16(2):439‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCormick 1992 {published data only}

- McCormick KA, Burgio LD, Engel BT, Scheve, A, Leahy E. Urinary incontinence: an augmented prompted void approach. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 1992;18(3):3‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDowell 1992 {published data only}

- McDowell BJ, Dombrowski M, Vaccari KM, Craig RL, Rodriguez E, Burgio KL. Behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence in patients with demential of the Alzheimer's type. Gerontologist. 1992; Vol. 32:163.

O'Brien 1991 {published data only}

- O'Brien J, Austin M, Sethi P, O'Boyle P. Urinary incontinence: prevalence, need for treatment and effectiveness of intervention by nurse. British Medical Journal 1991;303(6813):1308‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ouslander 1988 {published data only}

- Ouslander JG, Blaustein J, Connor A, Pitt A. Habit training and oxybutinin for incontinence in functionally disabled nursing home patients with detrusor hyperreflexia: a placebo controlled trial. Proceedings of the International Continence Society (ICS), 17th Annual Meeting, 2‐5 Sept, Bristol, UK. 1987:153‐4. [9036]

- Ouslander JG, Blaustein J, Connor A, Pitt A. Habit training and oxybutynin for incontinence in nursing home patients: a placebo‐controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36(1):40‐6. [509] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ouslander 1995 {published data only}

- Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, Fingold S, Nigam JG, Tuico E, et al. Does oxybutynin add to the effectiveness of prompted voiding for urinary incontinence among nursing home residents? A placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1995;43(6):610‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Proctor 1999 {published data only}

- Proctor R, Burns A, Powell HS, Tarrier N, Faragher B, Richardson G, et al. Behavioural management in nursing and residential homes: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 1999;354(9172):26‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramsay 1996 {published data only}

- Ramsay IN, Ali HM, Hunter M, Stark D, McKenzie S, Donaldson K, et al. A prospective randomised controlled trial of in‐patient versus outpatient continence programs in the treatment of urinary incontinence in the female. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 1996;7(5):260‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saltmarche 1991 {published data only}

- Saltmarche A, Pringle DM, Reid DW, Zorzitto M. Habit retraining: An incontinence study that leaked. Neurourology and Urodynamics 1991;10(4):413‐4. [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1983 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, Traughber B, Morgan DB, Embry JE, Binion AF, Coleman A. Management of geriatric incontinence in nursing homes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 1983;16(2):235‐41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1988 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, Sowell VA, Hu TW, Traughber B. Reduction of urinary incontinence in nursing homes: does it reduce or increase costs?. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1988;36:34‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1989 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF. Treatment of urinary incontinence in nursing homes patients by prompted voiding. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1990;38:356‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Traughber B, Sowell VA, Newman DR, Petrilli CO, Ory M. Prompted voiding treatment of urinary incontinence in nursing home patients: A behavior management approach for nursing homes staff. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1989;37(11):1051‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1990 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, Newman DR, Fogarty T. Management of patient continence in long‐term care facilities. The Gerontologist 1990;30(3):373‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1991 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, Newman DR, Fogarty TE, Wallston K, Ory M. Assessment and quality control of incontinence care in long‐term nursing facilities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1991;39:165‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1993 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, Newman D, White M, Abbey J, Wallston KA, Fogarty R, et al. Maintaining continence in nursing home residents through the application of industrial quality control. The Gerontologist 1993;33(1):114‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 1995 {published data only}

- Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Ouslander JG, Simmons SF, Nitta M. Functional incidental training, mobility performance, and incontinence care with nursing home residents. Journal of The American Geriatrics Society 1995;43(12):1356‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schnelle 2002 {published data only}

- Bates‐Jensen BM, Alessi CA, Al Samarrai NR, Schnelle JF. The effects of an exercise and incontinence intervention on skin health outcomes in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2003;51(3):348‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, Al Samarrai NR, Beck JC, Ouslander JG. Translating clinical research into practice: a randomized controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2002;50(9):1476‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Kapur K, Alessi C, Osterweil D, Beck JG, Al Samarrai NR, et al. Does an exercise and incontinence intervention save healthcare costs in a nursing home population?. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2003;51(2):161‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Schnelle JF. Effects of an exercise and scheduled‐toileting intervention on appetite and constipation in nursing home residents. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 2004;8(2):116‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sogbein 1982 {published data only}