Abstract

Background

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent and disabling disorder. Evidence that PTSD is characterised by specific psychobiological dysfunctions has contributed to a growing interest in the use of medication in its treatment.

Objectives

To assess the effects of medication for post traumatic stress disorder.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group specialised register (CCDANCTR‐Studies) on 18 August 2005, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library issue 4, 2004), MEDLINE (January 1966 to December 2004), PsycINFO (1966 to 2004), and the National PTSD Center Pilots database. Reference lists of retrieved articles were searched for additional studies.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacotherapy for PTSD.

Data collection and analysis

Two raters independently assessed RCTs for inclusion in the review, collated trial data, and assessed trial quality. Investigators were contacted to obtain missing data. Summary statistics were stratified by medication class, and by medication agent for the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Dichotomous and continuous measures were calculated using a random effects model, heterogeneity was assessed, and subgroup/sensitivity analyses were undertaken.

Main results

35 short‐term (14 weeks or less) RCTs were included in the analysis (4597 participants). Symptom severity for 17 trials was significantly reduced in the medication groups, relative to placebo (weighted mean difference ‐5.76, 95% confidence intervals (CI) ‐8.16 to ‐3.36, number of participants (N) = 2507). Similarly, summary statistics for responder status from 13 trials demonstrated overall superiority of a variety of medication agents to placebo (relative risk 1.49, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.73, number needed to treat = 4.85, 95% CI 3.85 to 6.25, N = 1272). Medication and placebo response occurred in 59.1% (N = 644) and 38.5% (628) of patients, respectively. Of the medication classes, evidence of treatment efficacy was most convincing for the SSRIs.

Medication was superior to placebo in reducing the severity of PTSD symptom clusters, comorbid depression and disability. Medication was also less well tolerated than placebo. A narrative review of 3 maintenance trials suggested that long term medication may be required in treating PTSD.

Authors' conclusions

Medication treatments can be effective in treating PTSD, acting to reduce its core symptoms, as well as associated depression and disability. The findings of this review support the status of SSRIs as first line agents in the pharmacotherapy of PTSD, as well as their value in long‐term treatment. However, there remain important gaps in the evidence base, and a continued need for more effective agents in the management of PTSD.

Plain language summary

Medication for post traumatic stress disorder

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occurs after exposure to significant trauma and results in enormous personal and societal costs. Although traditionally treated with psychotherapy, there is increasing recognition of a theoretical basis for medication treatments. This was a systematic review of 35 short‐term randomised controlled trials of pharmacotherapy for PTSD (4597 participants). A significantly larger proportion of patients responded to medication (59.1%) than to placebo (38.5%) (13 trials, 1272 participants). Symptom severity was significantly reduced in 17 trials (2507 participants). The largest trials showing efficacy were of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, with long‐term efficacy also observed for these medications.

Background

Although the phenomenon of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has long been recognised (for example as "shell shock" or "combat neurosis"), it is only relatively recently that this disorder has been officially recognised in the psychiatric nomenclature (APA 1980). Diagnostic criteria for PTSD provided by the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III) encouraged research on the epidemiology, psychobiology, and treatment of PTSD. Subsequent epidemiological research determined that the disorder is highly prevalent in a wide range of settings, particularly in those subjects who have been exposed to significant traumas (Breslau 1991; Davidson 1991; Kessler 1995). In addition, there is growing evidence that PTSD results in enormous personal and societal costs; this is based on chronicity of symptoms, high comorbidity of psychiatric and medical disorders, marked functional impairment, and estimations of economic costs (Solomon 1997; Brunello 2001).

By definition prior psychological trauma plays a causal role in PTSD, and psychotherapy has been widely employed in its management. Although psychodynamic psychotherapy has long been the mainstay of treatment, there have been few controlled studies of this modality (Brom 1989; Gersons 2000). Furthermore, the value of so‐called psychological debriefing in the immediate aftermath of trauma remains to be proven (Rose 1998; Rose 2002). Nevertheless, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that cognitive‐behavioural and similar psychotherapies are indeed effective in the treatment of PTSD (Keane 1989; Solomon 1992; Glynn 1995; Sherman 1998; van Etten 1998; Harvey 2003; Bisson 2005; Bradley 2005; NICE 2005).

There has also been increasing recognition, however, that PTSD is characterised by specific psychobiological dysfunctions (Yehuda 1995; Bonne 2004; Charney 2004), so providing a rationale for the use of medication treatments. PTSD is characterised by different symptom clusters, including intrusive/re‐experiencing, avoidant/numbing, and hyperarousal symptoms, and it is possible that each is mediated by different neurobiological mechanisms (Charney 1993), which may be normalised by specific pharmacological interventions. Certainly, there is growing evidence for rather specific dysregulations of neurotransmitter systems (including the serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine systems) and neuroendocrine systems (including the hypothalamus‐pituitary‐adrenal axis), as well as for structural and functional neuranatomical abnormalities in PTSD (Charney 1993; Yehuda 1995; Canive 1997; Connor 1998; Hull 2002; Bremner 2004).

Thus, whereas an older model was that medications might be valuable primarily as an adjunct to psychotherapy techniques in post‐traumatic reactions (Sargent 1940), contemporary psychobiological theory speculates that comorbid substance use in PTSD may represent an attempt at "self‐medication" and that prescribed medication may be able to play a primary role in preventing or reversing the dysfunctions of PTSD (Charney 1993; Charney 2004). Furthermore, several psychiatric disorders are often found comorbid with PTSD disorders (Kessler 1995), and certain of these are known to respond to medication. Indeed, the position that medication treatment may be useful in PTSD seems to have gained gradually increasing acceptance (van der Kolk 1983; Wise 1983; Friedman 1988; Friedman 1991; Faustman 1989; Walker 1989; Silver 1990; Allodi 1991; Davidson 1992; Davidson 1997a; Davidson 2000; Marshall 1996; Marshall 1998a; Shalev 1996; Connor 1998; Foa 1999; Cyr 2000; Marshall 2000; Asnis 2004; Ursano 2004).

Early reports of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD focused on the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (Hogben 1981; White 1983; Burstein 1984; Milanes 1984; Falcon 1985; Bleich 1986; Davidson 1987; Lerer 1987; Frank 1988; Shestatzky 1988; Davidson 1989; Irwin 1989; Reist 1989; Olivera 1990; Chen 1991; Kosten 1991; Basoglu 1992; Rubin 1993; Demartino 1995). More recent work has focused on the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Davidson 1990;Burdon 1991; McDougle 1991; De Boer 1992; Dominiak 1992; Shay 1992; Nagy 1993; Fichtner 1994; Kline 1994; van der Kolk 1994; Brady 1995; Marmar 1996; Nagy 1996; Rothbaum 1996; Connor 1998; Davidson 1998a; Marshall 1998b; Marshall 2001; Brady 2000; Hertzberg 2000; Smajkic 2001; Tucker 2001; Martenyi 2002a; Zohar 2002; Tucker 2003; Brady 2004), and the serotonin antagonists and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs) (Liebowitz 1989; Hertzberg 1996; Hertzberg 1998; Hidalgo 1999).

Several other newly introduced antidepressants have also been studied (Katz 1994; Baker 1995 a; Neal 1997; Canive 1998; Davidson 1998a; Hamner 1998; Connor 1999; Davis 2000; Davis 2001; Davidson 2003). In addition, benzodiazepines (Dunner 1985; Lowenstein 1988; Braun 1990), beta‐blockers (Kolb 1984; Famularo 1988), buspirone (Simpson 1991; Wells 1991; Duffy 1992; Duffy 1994; LaPorta 1992; Fichtner 1994), clonidine (Kolb 1984; Kinzie 1989; Harmon 1996) and guanfacine (Horrigan 1996), cyproheptadine (Brophy 1991; Gupta 1998), d‐cycloserine (Heresco‐Levy 2002), inositol (Kaplan 1996), mood‐stabilizers (Kitchner 1985; Lipper 1986; Stewart 1986; van der Kolk 1987; Wolf 1988; Irwin 1989; Fichtner 1990; Fesler 1991; Szymanski 1991; Keck 1992; Forster 1994; Looff 1995; Ford 1996; Hertzberg 1999); typical (Bleich 1986; Dillard 1993) and atypical neuroleptics (Hamner 1996; Leyba 1998; Izrayelit 1998; Burton 1999; Butterfield 2001; Hamner 2003); and opioids (Glover 1993) have also received attention.

A systematic review of studies of pharmacotherapy for PTSD may be useful in tackling several questions for the field. Firstly, is pharmacotherapy in fact an effective form of treatment in PTSD? Given the preponderance of psychological models and evidence for the efficacy of certain forms of psychotherapy in PTSD (Bisson 2005), the role of pharmacotherapy remains debatable for many. In a recently published guideline for the treatment of PTSD, the National Institute of Clinical Evidence (NICE) recommended that preference be given to trauma‐focused psychological therapy over pharmacotherapy as a routine first line treatment for this disorder (NICE 2005). For those who accept a more dominant role for pharmacotherapy, questions about appropriate dose and duration arise, with current clinical recommendations suggesting that the SSRIs, for example, are prescribed at doses that increase to maximally effective/tolerated levels over a period of at least eight weeks (Foa 1999; Ballenger 2000; Ballenger 2004).

Secondly, are particular medication classes more effective in the treatment of symptoms and/or more acceptable to the patient in terms of adverse events than others? The use of novel agents (such as the serotonergic antidepressants) for PTSD in recent years raises the question of how these compare with older agents. Some recommendations, such as the expert consensus guideline series for the treatment of post traumatic stress disorder (Foa 1999), have suggested that the SSRIs, nefazodone, and venlafaxine are first‐line medications for the treatment of PTSD , with benzodiazepines and mood‐stabilisers having a role in patients with certain kinds of symptoms. Other recommendations have highlighted paroxetine and mirtazapine (NICE 2005). Support for such recommendations requires ongoing assessment of the literature on RCTs.

Thirdly, can a systematic review of RCTs provide information about the most important factors affecting pharmacotherapy response? Clinical factors, such as the kind of pre‐existing trauma (e.g. combat‐related or not), the duration of symptoms, and the presence of comorbid depression, early childhood trauma, and "secondary gain" for symptoms (for example, patients in ongoing litigation or receiving financial compensation) have all been suggested to play a role (Davidson 1993; van der Kolk 1994; Marshall 1998b; Davidson 2000). Methodological factors such as the duration of the trial or inclusion of patients with a minimal degree of symptom severity, may also affect treatment response. It is possible that the database of RCTs in PTSD may include information about some of these variables.

A number of reviews of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD have indeed been published in recent years (van der Kolk 1983; Friedman 1988; Friedman 1991; Davidson 1992; Davidson 1997a; Marshall 1996; Marshall 1998a; Solomon 1992; Shalev 1996; Otto 1996; Connor 1998; Albucher 2002; Asnis 2004). These reviews have been useful in summarising the existing research, pointing to methodological flaws, and outlining areas for future research. Nevertheless, few of these reviews have employed a systematic search strategy. It has recently been determined that even MEDLINE searches may miss over half of all RCTs in specialised health care journals (Hopewell 2002). Furthermore, few studies have estimated the effects of medication (Penava 1996; Davidson 1997a; van Etten 1998). Interestingly, in their meta‐analysis, Penava (Penava 1996) noted that effect size correlated with increased serotonergic specificity of the antidepressant. Further reviews in this area need to adhere to Cochrane Collaboration (Mulrow 1997) or similar (Moher 1999) guidelines for systematic identification of trials, investigation of sources of heterogeneity, measurement of methodological quality, and estimation of the effects of intervention.

The authors aimed to undertake a systematic review of randomised controlled (RCTs) of the pharmacotherapy of post traumatic stress disorder, following the guidelines and using the software of the Cochrane Collaboration.

Objectives

1. To identify and review all RCTs, including placebo controlled and comparative trials, of the pharmacotherapy of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), whether published or unpublished.

2. To provide an estimate of the effects of medication in reducing PTSD symptoms.

3. To determine whether particular classes of medication are more effective and/or acceptable than others in the treatment of PTSD.

4. To identify which factors (clinical, methodological) predict response to pharmacotherapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (placebo controlled and comparative trials) completed prior to the end of 2004 were considered for inclusion. Publication is not necessarily related to study quality and indeed publication may imply certain biases (Easterbrook 1991; Dickersin 1992; Scherer 1994), so unpublished abstracts and reports were also considered. Studies were not limited to any particular language. Differences between trials (for example, sample size, trial duration) were not used to exclude studies.

Types of participants

All studies of subjects with PTSD (as determined by the study authors) were included. There was no restriction on the basis of different diagnostic criteria for PTSD, duration and severity of PTSD symptoms, presence of comorbid disorders, or age and gender of subjects. However, these descriptors were tabulated in order to address the question of their possible impact on the effects of medication.

Types of interventions

The review focused only on medication treatments, in which the comparator was a placebo (active or non‐active) or other medication. A parallel review of the psychotherapy of PTSD has recently been completed by members of the Cochrane Collaboration (Bisson 2005). Trials in which ongoing pharmacotherapy is supplemented with augmentation medication (Hamner 1997;Heresco‐Levy 2002;Stein 2002; Hamner 2003;Monnelly 2003;Raskind 2003) will be included in a separate review of pharmacotherapy for treatment‐resistant anxiety disorders (Dhansay 2005). RCTs of medication prophylaxis for PTSD (Gelpin 1996;Pitman 2002; Schelling 2004) have also been reserved for a future Cochrane protocol.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes PTSD symptom and symptom cluster response was determined from the total score on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake 1990), a symptom severity measure that is increasingly used in RCTs of PTSD.

Treatment response (responders versus non‐responders) was determined from the Clinical Global Impressions scale ‐ improvement item (CGI‐I), or closely related measure such as the Duke Global Rating for PTSD scale (Davidson 1998b), or a closely related definition (Brady 2000). Responders are defined on the CGI‐I as those with a score of 1 = "very much" or 2 = "much" improved (Guy 1976); this is a widely used global outcome measure in RCTs of PTSD, where it appears robust (Davidson 1997b).

Secondary outcomes

PTSD symptom response was assessed for those trials which used other continuous measures of symptom severity besides the CAPS, as well as from summary statistics from self‐rated scales such as the Impact of Events Scale (IES) (Horowitz 1979), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (Davidson 1997c). Self‐rated scales were frequently the only outcome measures used in older trials, and may continue to have a role in clinical practice. The efficacy of medication in alleviating symptoms within the three symptom clusters characteristic of PTSD (re‐experiencing/intrusion, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal) was determined using the CAPS‐B, CAPS‐C, and CAPS‐D subscales of the CAPS, as well as the relevant subscales of the self‐rated outcome measures.

The response of comorbid symptoms was measured by (a) depression scales, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961), the Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1959), and the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), and (b) anxiety scales, such as the Covi Anxiety Scale (CAS) (Covi 1984) and the Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAM‐A) (Hamilton 1960).

Quality of life measures, as well as measures of functional disability, such as the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), which includes subscales to assess work, social and family related impairment (Sheehan 1996), were also included when provided, to address the question of medication effectiveness.

The total proportion of participants who withdrew from the RCTs due to treatment emergent adverse events was included in the analysis as a surrogate measure of medication acceptability, in the absence of other more direct indicators of acceptability.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic Searches 1. The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR‐Studies) was searched using the following search strategy on 18 August 2005:

Diagnosis = Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorders

and

"Antidepressive Agents" OR "Monoamine Oxidase InhibitORs" OR "Selective Serotonin Reuptake InhibitORs" OR "Tricyclic Drugs" OR Acetylcarnitine OR Alaproclate OR Amersergide OR Amiflamine OR Amineptine OR Amitriptyline OR Amoxapine OR Befloxatone OR Benactyzine OR Brofaromine OR Bupropion OR Butriptyline OR Caroxazone OR ChlORpoxiten OR Cilosamine OR Cimoxatone OR Citalopram OR Clomipramine OR ClORgyline OR ClORimipramine OR Clovoxamine OR Deanol OR Demexiptiline OR Deprenyl OR Desipramine OR Dibenzipin OR Diclofensine OR Dothiepin OR Doxepin OR Duloxetine OR Escitalopram OR Etoperidone OR Femoxetine OR Fluotracen OR Fluoxetine OR Fluparoxan OR Fluvoxamine OR Idazoxan OR Imipramine OR Iprindole OR Iproniazid OR isocarboxazid OR Litoxetine OR Lofepramine OR Maprotiline OR Medifoxamine OR Melitracen OR Metapramine OR Mianserin OR Milnacipran OR Minaprine OR Mirtazapine OR Moclobemide OR Nefazodone OR Nialamide OR Nomifensine OR NORtriptyline OR Noxiptiline OR Opipramol OR Oxaflozane OR Oxaprotiline OR Pargyline OR Paroxetine OR Phenelzine OR Piribedil OR Pirlindole OR Pivagabine OR Prosulpride OR Protriptyline OR Quinupramine OR Reboxetine OR Rolipram OR Sertraline OR Setiptiline OR Teniloxine OR Tetrindole OR Thiazesim OR Thozalinone OR Tianeptine OR Toloxatone OR Tomoxetine OR Tranylcypromine OR Trazodone OR Trimipramine OR Venlafaxine OR Viloxazine OR Viqualine OR Zimeldine.

2. Additional searches were carried out on MEDLINE (via PubMed), PsycINFO, and The National PTSD Center Pilots database.

The MEDLINE search query, as derived from a highly sensitive search strategy developed by Robinson and Dickersin (Robinson 2002), was the following:

(randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR ("latin square" [tw]) OR placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR cross‐over studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animal [mh] NOT human [mh]) AND (Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic [mh:noexp] OR "posttraumatic stress disorder" [tw] OR "post traumatic stress disorder" [tw] OR PTSD [tw]) AND (pharmacother* [tw] OR medicat* [tw] OR drug* [tw] OR Drug Therapy [mh]). The PsycINFO search used the following search query: ("randomisation" OR "randomization") OR "controlled" AND ("post‐traumatic" OR posttraumatic) AND (medication OR pharmacotherapy OR treatment). PsycINFO includes the Dissertation Abstracts International database ‐ a database of unpublished dissertations.

The National PTSD Center Pilots database contains published and unpublished articles on PTSD. It was searched using the following search query: (randomisation or randomization) or controlled AND (post‐traumatic OR posttraumatic) AND (medication OR pharmacotherapy).

3. Unpublished trials were retrieved via the metaRegister module [mRCT] of the Controlled Trials database (http://www.controlled‐trials.com). The search terms used were "PTSD", "posttraumatic stress disorder", and "post traumatic stress disorder".

An initial broad strategy was undertaken to find not only RCTs, but also open‐label trials, as well as journal and chapter reviews of the pharmacotherapy of PTSD.

Reference Lists Additional RCTs were sought in reference lists of the retrieved articles and included studies in any language.

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection RCTs identified from the search were independently assessed for inclusion by two raters, based on information included in the abstract and/or main body of the trial report. RCTs which both raters regarded as satisfying the inclusion criteria specified in the "criteria for considering studies" section were collated. Studies for which additional information is required in order to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review have been listed in the "studies awaiting assessment" table in the Review Manager (RevMan) software, pending the availability of this information. Any disagreements in assessment and collation were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction Spreadsheet forms were designed for the purpose of recording descriptive information, summary statistics of the outcome measures, the quality scale ratings, and associated commentary. The data was subsequently exported to the RevMan software, which was used to conduct the meta‐analysis. Where information was missing, the reviewers contacted investigators by email in an attempt to obtain this information. In the case of one trial for which it was not possible to obtain exact treatment response figures (Marshall 2001), one of the reviewers used a ruler to estimate the mean number of responders within the comparison groups from a graph contained within the original trial report.

Data synthesis The following information was collated from each trial (additional information can be found in the "Characteristics of Included Studies" table):

(a) Description of the trials, including the primary researcher, the year of publication, and the source of funding.

(b) Characteristics of the interventions, including the number of participants randomised to the treatment and control groups, the number of total drop‐outs per group as well as the number that dropped out due to adverse effects, the dose of medication and the period over which it was administered, and the name and class of the medication (SSRIs, TCAs, MAOIs and "other medication").

(c) Characteristics of trial methodology, including the diagnostic (eg. DSM‐IV (APA 1994)) and exclusionary criteria employed, the screening instrument used (eg. the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV (SCID) (Spitzer 1996)) for both the primary and comorbid diagnoses, the presence of comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD), the use of a placebo run‐in or of a minimal severity criterion, the number of centres involved, and the trial's methodological quality (see below).

(d) Characteristics of participants, including gender distribution and mean and range of ages, mean length of time with PTSD symptoms, whether they have been treated with the medication in the past (treatment naivety), the number of participants in the sample with MDD, the number who experienced combat trauma, and the baseline severity of PTSD, as assessed by the trial's primary outcome measure or another commonly employed scale.

(e) Outcome measures employed (primary and secondary), and summary continuous (means and standard deviations (SD)) and dichotomous (number of responders) data. Additional information included whether data reflected the intent‐to‐treat (ITT) with last observation carried forward (LOCF) or mixed methods (MM) sample, or whether a completer/observed cases (OC) sample was reported.

Data analysis

Summary statistics for categorical and continuous measures were obtained from a random effects model (the random effects model includes both within‐study sampling error and between‐studies variation in determining the precision of the confidence interval (CI) around the overall effect size, whereas the fixed effects model takes only within‐study variation into account). The summary statistics were expressed in terms of an average effect size for each subgroup, as well as by means of 95% CIs.

Cross‐over trials were only included in the calculation of summary statistics when it was (a) possible to extract medication and placebo/comparator data from the first treatment period, or (b) when the inclusion of data from both treatment periods was justified through a wash‐out period of sufficient duration as to minimise the risk of carry‐over effects (a minimum of two weeks or longer in the case of trials assessing the efficacy of agents with extended half‐lives, such as the SSRI, fluoxetine (Gury 1999)). In the latter case, data from both periods were only included when it was possible to determine the correlation between participants' responses to the interventions in the different phases (Elbourne 2002).

In recognition of the possibility of differential effects for different types of medication, all of the comparisons were stratified by medication class. Medications which could not be classified as either SSRIs, TCAs or MAOIs were placed in a separate category, labelled "other medication". In addition, in the case of the SSRIs, in view of the large number of SSRI trials, comparisons between medication and placebo on the primary outcome measures and on the number of drop‐outs due to drug‐related adverse events were stratified by individual agents. Categorical data Relative risk (RR) of failure to respond to treatment was used as the summary statistic for the dichotomous outcome of interest (CGI‐I or related measure). RR was used instead of odds ratios, as odd ratios tend to underestimate the size of the treatment effect when the occurrence of the adverse outcome of interest is common (as was the case in this review, with an anticipated non‐response greater than 20%) (Deeks 2003), and because of the greater ease with which this statistic can be interpreted. Number needed to treat (NNT) was also included. The NNT is calculated as the inverse of the absolute risk reduction between the medication and control groups (McQuay 1997). It provides an indication of the number of patients who require treatment with medication before a single additional patient in the medication group responds to treatment, relative to the control group. The confidence intervals for the NNT were only calculated for significant treatment effects, given the difficulty of interpreting CIs which contain infinity (Altman 1998).

Continuous data Weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated for continuous summary data obtained from studies that employed the CAPS. Alternatively, in cases in which a range of scales were employed, such as in the assessment of symptom severity on the self‐rated IES and DTS scales, or in the assessment of comorbid depression on the MADRS and HAM‐D, the standardised mean difference (SMD) was determined. This method of analysis standardises the differences between the means of the treatment and control groups in terms of the variability observed in the trial.

In the case of data from trials employing multiple fixed doses of medication, the bias introduced through comparing the summary statistics for multiple groups against the same placebo control was avoided by pooling the means and standard deviations across all of the treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm. For the same reason, outcome comparisons were limited to those between only one medication and placebo in trials which compared several different medications with placebo. Selection of medication for analysis was done (prior to analysis, to avoid introducing bias) on the basis of which of the three major medication classes (TCAs, MAOIs, SSRIs) was least well represented. In addition, when including summary statistics from the self‐rated scales, preference was given to data from the DTS over the IES in trials which used both scales, given the late inclusion in the former of a subscale assessing the hyperarousal symptom cluster (Weiss 1997), and concerns regarding the psychometric properties of the IES subscales (Creamer 2003).

Quality assessment There has been some debate about how best to measure the quality of trials, and further work in this area remains necessary (Berlin 1999). In this review, one of the reviewers assessed the quality of the trials by means of the CCDAN Quality of Research Scale (CCDAN‐QRS) (Moncrieff 1999) (http://www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/IoP/ccdan/qrs.htm). This 23 item scale assesses a range of features such as sample size, the duration of the intervention, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and whether or not the power of the trial to detect a treatment effect was calculated. In addition, data for other trial characteristics which have been recognised as a potential sources of bias, such as the method used in generating the allocation sequence, the concealment of allocation, whether outcome assessment was blinded, and the number of participants lost to follow up, were also collated. This was regarded as necessary given doubts concerning the usefulness of an overall quality score from a scale composed of multiple items (Alderson 2003).

Heterogeneity Heterogeneity of treatment response, that is whether the differences between the results of trials were greater than would be expected by chance alone, was assessed visually from the forest plot of RR. It was also determined by means of the chi‐square test of heterogeneity, with a significance level of less than 0.10 interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity, given the low power of the chi squared statistic when the number of trials is small (Deeks 2003). In addition, the I‐square heterogeneity statistic reported by RevMan was used to test the robustness of the chi squared statistic to differences in the number of trials included in the groups being compared within each subgroup analysis (Higgins 2003). Differences on continuous measures in medication efficacy between these groups were assessed by means of Deeks' stratified test of heterogeneity (Deeks 2001). This method subtracts the sum of the chi squared statistics for each of the groups from the total chi squared for the subgroup analysis, to provide a measure (Qb) of heterogeneity between groups. Differences in treatment response on the CGI‐I was determined by whether the confidence intervals for the effect sizes of the subgroups overlap. This method was chosen in preference to the stratified test, due to inaccuracies in the calculation in RevMan of the chi squared statistic for dichotomous measures (Deeks 2003).

Subgroup analyses Subgroup analyses (Thomson 1994) were undertaken in order to assess the degree to which methodological differences between trials might have systematically influenced differences observed in the primary treatment outcomes.

The trials were grouped according to the following methodological sources of heterogeneity:

The involvement of participants from a single centre or multiple centres. Single‐centre trials are more likely to be associated with lower sample size but less variability in clinician ratings.

Whether or not trials were industry funded. In general, published trials which are sponsored by pharmaceutical companies appear more likely to report positive findings than trials which are not supported by for‐profit companies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Baker 2003).

In addition, the following criteria were used to assess the extent of clinical sources of heterogeneity:

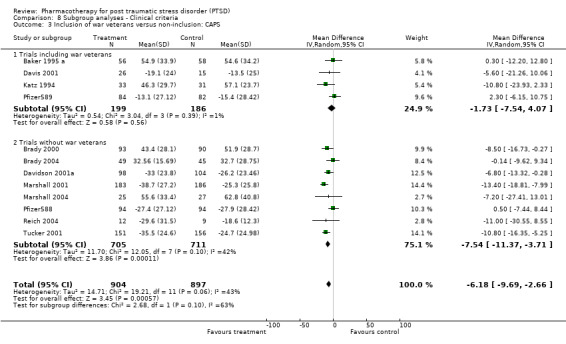

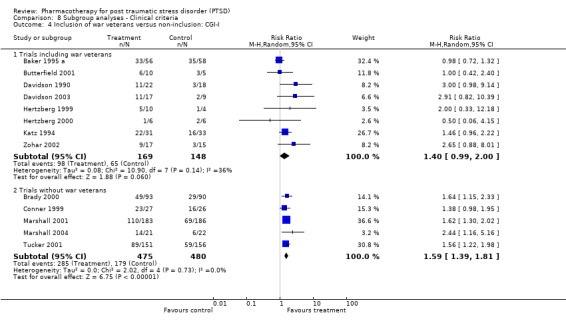

Whether or not the sample included combat veterans (this subgroup has been regarded as more resistant to treatment, and is arguably more likely to have more chronic and severe symptoms, to have comorbid depression, and to be male). For the purpose of this review, those trials for which 10 percent or fewer of the sample consisted of war veterans were classified as non‐combat veteran RCTs.

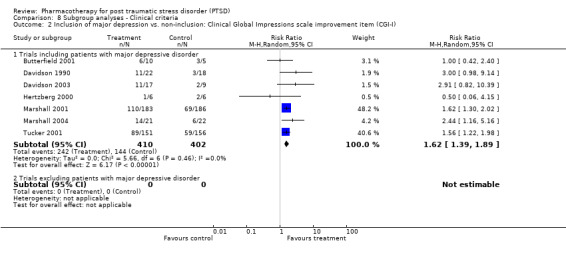

Whether or not the sample included patients diagnosed with major depression. Such an analysis might assist in determining the extent to which the efficacy of a medication agent in treating PTSD is independent of its ability to reduce symptoms of depression, an important consideration given the classification of many of these medications as antidepressants.

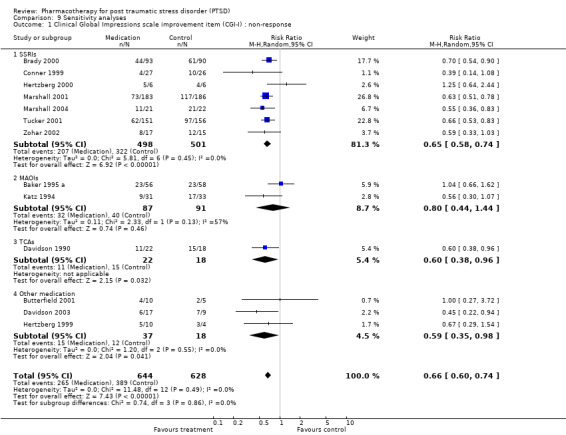

Sensitivity analysis Sensitivity analyses, which determine the robustness of the reviewers' conclusion to methodological assumptions made in conducting the meta‐analysis, were also performed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether treatment response on the CGI‐I differed as a result of:

Treatment response versus non‐response as the unit of comparison in determining medication efficacy. This comparison is regarded as necessary given concerns that the former may result in less consistent summary statistics than the latter (Deeks 2002).

The exclusion of participants who were lost to follow up (LTF). This was determined through a "worst case/best case" scenario (Deeks 2003). In the worst case, all the missing data for the treatment group were recorded as non‐responders, whereas in the best case, all missing data in the control group were treated as non‐responders. (In the case of the one SSRI (Marshall 2004) and MAOI trial (Baker 1995 a) which only reported total LTF, the ratio of participants who dropped out in the medication and placebo group was determined from the average ratio between these groups for those RCTs in the respective classes which did provide this information). Should the conclusions regarding treatment efficacy not differ between these two comparisons, it can be assumed that missing data in trial reports do not have a significant influence on outcome.

Publication bias Publication bias was determined by visual inspection of a funnel plot of treatment response.

Results

Description of studies

The review included 35 short term RCTs of PTSD (4597 participants), three of which contained a maintenance component (Davidson 2001a, Marshall 2004, Martenyi 2002a)(see Comparison 06). Of the 35 trials, 30 were published, and all of these publications were in English. A placebo comparison group was employed in all but four of the trials (McRae 2004 and Saygin 2002 compared nefazodone with the SSRI sertraline, while Smajkic 2001 compared the efficacy of the SSRIs sertraline, paroxetine and the serotonin ‐ noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine. Chung 2004 assessed the efficacy and tolerability of mirtrazapine against that of sertraline). Of the remaining 31 short term RCTs, 17 of the trials included a SSRI treatment arm (one citalopramine, six fluoxetine, four paroxetine, seven sertraline), two trials a TCA intervention (one amitriptyline, one desipramine), four a MAOI intervention (two brofaromine, two phenelzine), and seven studies employed an intervention classified as "other medication". This last category included one benzodiazepine (alprazolam), two antipsychotics (olanzapine and risperidone), one anticonvulsant (lamotrigine), one second messenger system precursor (inositol), one SNRI (venlafaxine) and two novel antidepressants (mirtazapine and nefazodone). The SSRI trials can be distinguished from the non‐SSRI trials on a number of different study characteristics. The SSRI trials were significantly larger (mean = 184 participants) on average than the non‐SSRI trials (mean = 41 participants) (one‐sided Wilcoxon Mann‐Whitney test: W = 208, P = < 0.01), even when adjusting for the smaller number of participants in the non‐SSRI crossover trials (through doubling the sample size). The majority of the 17 placebo controlled short term trials published since 2000 have included SSRIs (N = 13), with only two SSRI trials being published prior to 2000 (Conner 1999; van der Kolk 1994).

None of the four acute RCTs which employed a cross‐over design (Braun 1990; Kaplan 1996; Reist 1989; Shestatzky 1988) provided sufficient information for inclusion in the calculation of summary statistics. These trials were all small and of poor quality (mean CCDAN‐QRS score of 12), however, so their exclusion is unlikely to have had a significant effect on the primary outcomes of the meta‐analysis. (In brief: Braun 1990 compared an intervention of alprazolam with placebo using a sample of 16 outpatients over a period of 12 weeks. Kaplan 1996 investigated the efficacy of inositol for a sample of 13 patients from two different outpatient clinics. Reist 1989 conducted a crossover trial of the TCA, desipramine, in treating 27 combat veterans over a period of 10 weeks. Shestatzky 1988 assessed the efficacy of the MAOI phenelzine in a 12 week trial of 13 PTSD outpatients).

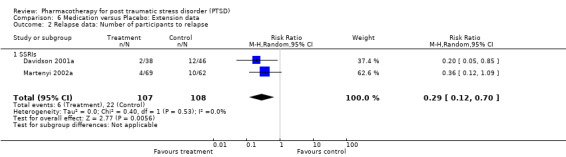

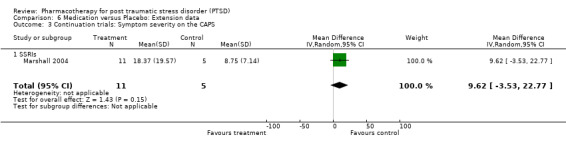

In determining the long‐term effects of medication, Marshall (2004) assessed whether 17 responders in the medication arm of a 10 week trial of paroxetine continued to respond after an additional maintenance period of 12 weeks. In a relapse‐prevention trial of sertraline, Davidson (2001) set out to determine whether 50 patients who were randomised to a placebo control for 28 weeks were more likely to experience clinical deterioration or relapse than those 46 patients randomised to a sertraline intervention for the same period. Participants in the relapse prevention phase of this trial had completed a 12 week acute RCT of sertraline, and had also met responder criteria following the subsequent open‐label administration of this medication for a period of six months. In another relapse‐prevention trial, Martenyi (2002) re‐randomised 131 responders to a 12 week short‐term RCT of fluoxetine to an additional 24 weeks of placebo or medication.

A great deal of clinical heterogeneity was observed across patients in the RCTs included this review. Of the 34 acute trials that provided information on the nature of the index trauma for PTSD, six were composed exclusively of war veterans (Chung 2004; Davidson 1990; Hertzberg 2000; Kosten 1991; Pfizer589; Reist 1989), 9 contained individuals exposed to "civilian" traumas, such as earthquakes and child molestation (Brady 2000; Brady 2004; Conner 1999; Marshall 2004; McRae 2004; Pfizer588; Reich 2004; Saygin 2002; Smajkic 2001) and 19 contained patients exposed to both combat‐related and civilian traumas (Baker 1995 a; Braun 1990; Butterfield 2001; Davidson 2001a; Davidson 2003; Davidson 2004; Davis 2001; Eli Lilly 2006; Hertzberg 1999; Kaplan 1996; Katz 1994; Marshall 2001; Martenyi 2002a; Shestatzky 1988; Tucker 2001; Tucker 2003; van der Kolk 1994; van der Kolk 2004; Zohar 2002).Of the 24 short‐term RCTs that providing information on comorbid psychopathology, 18 reported that the patients in the trials were diagnosed with other anxiety disorders besides PTSD, as classified according to DSM III, DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR criteria (Brady 2000; Brady 2004; Braun 1990; Butterfield 2001; Davidson 1990; Davidson 2001a; Davidson 2003; Davis 2001; Hertzberg 2000; Kaplan 1996; Marshall 2001; Marshall 2004; Pfizer589; Reich 2004; Saygin 2002; Shestatzky 1988; Tucker 2001; Tucker 2003).The most commonly reported comorbid anxiety was panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, which was reported for 8 of the 12 studies that distinguished between individual anxiety disorder diagnostic categories (Braun 1990; Butterfield 2001; Davidson 1990; Davis 2001; Marshall 2001; Marshall 2004; Saygin 2002; Tucker 2003),

Summary statistics for the sertraline arm of the Tucker 2003 trial were excluded from the analysis, in favour of including the data from the less well represented citalopram arm. Data from the venlafaxine group in the unpublished Davidson trial (Davidson 2004) was given preference to that from the sertraline arm, for the same reason. Summary statistics from the phenelzine arm of the Kosten 1991 trial were chosen above those from the imipramine arm in order to equalise the number of MAOI and TCA trials.

Risk of bias in included studies

Generation of Allocation Sequence The randomisation procedure employed was described in four trials. Computer generated random codes were employed in three of these trials (Conner 1999; Davidson 2001a; Martenyi 2002a), while an urn randomisation procedure was followed in Brady 2004.

Allocation Concealment Of the 35 short term RCTs, only five described the allocation sequence which was used in assigning participants to the treatment and comparison groups. Adequate allocation concealment (randomisation log kept by each trial's pharmacy division) was practised in three of these trials (Conner 1999; Davis 2001; McRae 2004). The remaining two trials did not provide sufficient information to determine the adequacy of the concealment used (Kaplan 1996; Martenyi 2002a).

Blinding of Outcome Assessment Although the majority of the trials were described as "double‐blinded", only six of the short term trials explicitly described the assessment of outcome as blinded (Braun 1990; Davidson 1990; Davis 2001; Marshall 2004; Shestatzky 1988; van der Kolk 2004). The extent to which blinding was preserved in those flexible dose trials which adjusted dosage on the basis of tolerability is unclear, however. Indeed, outcome was assessed independently of medication administration and side‐effect evaluation in only one RCT (Marshall 2004). Two comparative RCTs did not employ any form of blinding (Smajkic 2001; Chung 2004), whereas it is not clear whether blinding was undertaken in another (Saygin 2002).

Loss to follow up On average, about 31.3 percent (718 out of 2291) of the participants in the 24 short term RCTs that provided drop‐out data did not reach study endpoint, with the majority (N = 13) of these trials excluding over a quarter of the sample. Of the 13 trials, six did not attempt to include the withdrawals in the summary statistics through estimating outcomes by means of either LOCF or MM analyses (Braun 1990;Chung 2004;Davidson 1990;Eli Lilly 2006;Saygin 2002;Smajkic 2001).

Quality Score The average quality score on the CCDAN‐QRS for the published short term trials was 22.8 points (range: 11 to 31) out of a maximum of 46 points. On this scale, 19 trials failed either to provide a record of the exclusion criteria used, or to report the number of people excluded by these criteria, 16 provided inadequate details of the side effects experienced by group, six RCTs did not provide information about funding, and three RCTs (excluding crossover trials) did not provide information about the comparability of the medication and control groups. Quality ratings were not calculated for the unpublished trials, due to the lack of sufficient descriptive data for these studies.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome measures

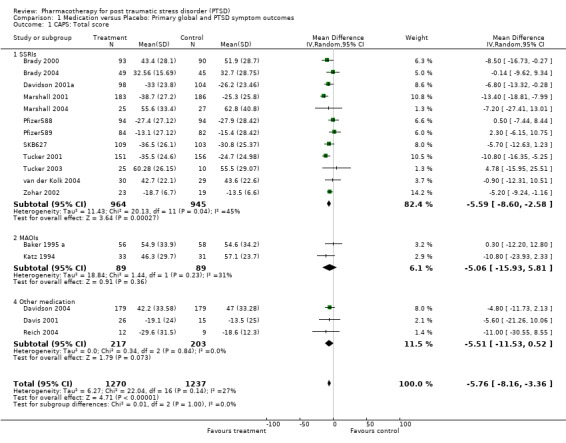

Significant reductions in symptom severity were observed for patients who received medication in 17 short term trials from which it was possible to retrieve data for this outcome. The mean total CAPS score for the medication group was 5.76 points lower (95% CI ‐8.16 to ‐3.36, N = 2507) than that for the placebo group. Evidence for the efficacy of the SSRIs (N = 12) was once again observed (WMD = ‐5.95, 95% CI ‐8.9 to ‐3, N = 1907), with this class of medication making the largest contribution to the overall effect size observed (weight = 82.4%).

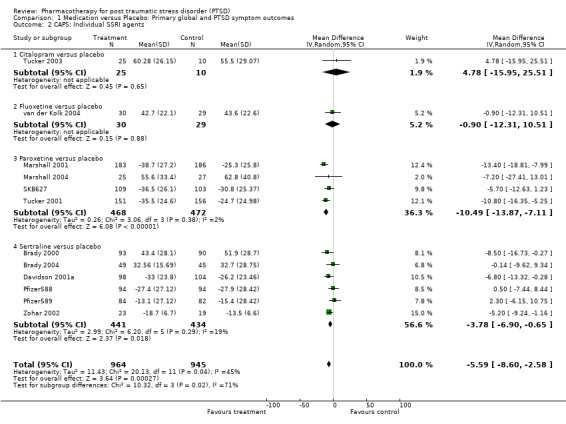

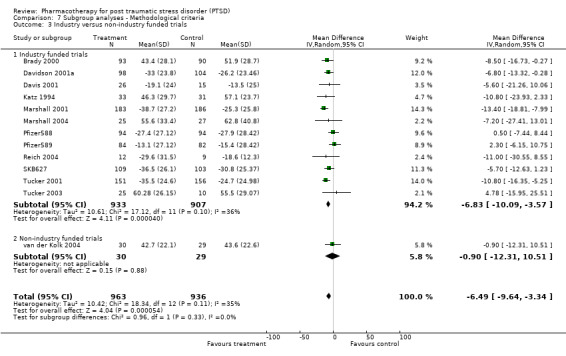

The comparison of the efficacy of particular SSRIs in reducing PTSD symptom severity provided evidence for the efficacy of both paroxetine (N = 4, WMD ‐10.49, 95% CI ‐13.87 to ‐7.11, N = 940) and to a lesser extent, sertraline (N = 6, WMD ‐3.78, 95% CI ‐6.9 to ‐0.65, N = 875), but not citalopram (N = 1, WMD ‐13.41, 95% CI ‐35 to 8.18, N = 33) or fluoxetine (N = 1, WMD ‐0.9, 95% CI ‐12.31 to 10.51, N = 59). The failure to detect a treatment effect for citalopram or fluoxetine presumably reflects the small samples, and hence low power, of these comparisons. There was no indication that brofaromine was more effective than placebo (N = 2, WMD ‐5.06, 95% CI ‐15.93 to 5.81, N = 178). Neither the single trials of the novel antidepressant nefazodone or the antipsychotic risperidone provided evidence of efficacy in reducing symptom severity (WMD ‐5.6, 95% CI ‐21.26 to 10.06, N = 41 and WMD ‐11, 95% CI ‐30.55 to 8.55, N = 21, respectively). This was also true of the single SNRI trial of venlafaxine (N = 1, WMD ‐4.8, 95% CI ‐11.73 to 2.13, N = 358).

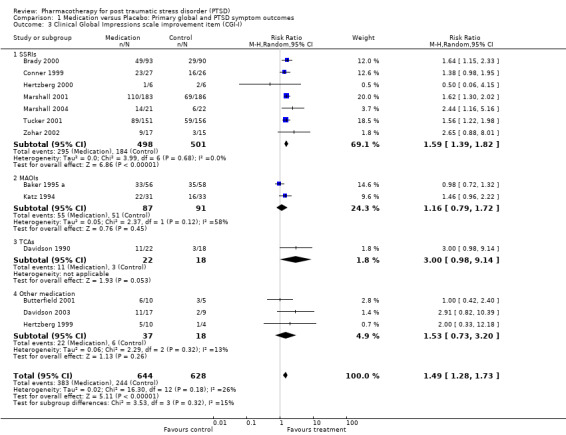

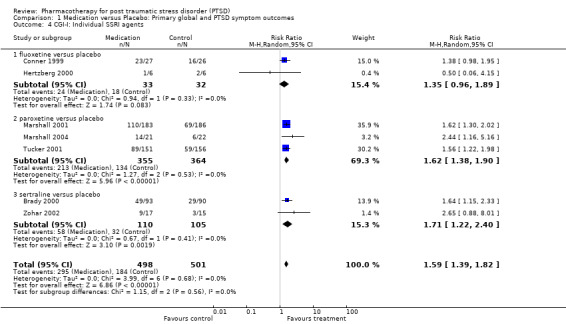

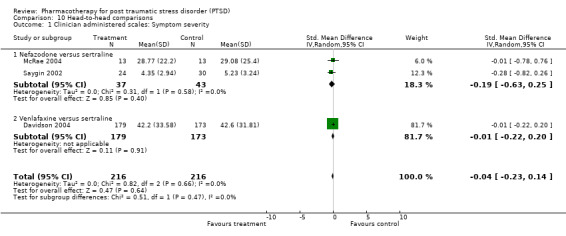

With regards to direct comparisons, no difference in the reduction of symptom severity was observed in the two head‐to‐head comparisons of nefazodone and sertraline (SMD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.25, N = 80), or in the single unpublished comparison of venlafaxine and sertraline (SMD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.20, N = 352). Although the only trial to directly compare mirtazapine and sertraline (Chung 2004) reported that treatment with mirtazapine resulted in a larger number of responders on the CAPS than sertraline after six weeks of treatment (treatment response was defined as a reduction of over 30% on the total score of this scale), the authors were unable to detect a difference in efficacy when comparing these groups on the total CAPS score. Patients who received medication were significantly more likely to be responders than those who received placebo in the 13 trials that provided data on this outcome (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.73; random effects model, N = 1272), as determined by response rates on the Clinical Global Impressions scale change item (or close equivalent). Response to medication occurred in 59.1% of subjects (N = 644), while response to placebo was seen in 38.5% of subjects (N = 628). The short term efficacy of medication treatment was observed for the SSRIs as a group (N = 7, RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.82, N = 999), to which the significant overall effect of medication on treatment response can once again primarily be attributed (weight = 69.1%).

The pattern of treatment response on the CGI‐I for the separate SSRI medications was similar to that observed for symptom severity, with both paroxetine (N = 3, RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.9, N = 719) and sertraline (N = 2, RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.4, N = 215) demonstrating efficacy. There was once again insufficient evidence to determine whether fluoxetine was effective in increasing the number of responders, relative to placebo (N = 2, RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.89, N =65). None of the individual trials of the TCA amitryptyline (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.98 to 9.14, N = 40), the novel antidepressant mirtazapine (RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.82 to 10.39, N = 26), the antipsychotic olanzapine (N = 1, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.4, N = 15), the anticonvulsant lamotrigine (N = 1, RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.33 to 12.18, N = 14), or the two trials of MAOI brofaromine (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.72, N = 178) was significantly more effective than placebo in increasing treatment response.

The NNT analysis revealed that each patient who was treated with medication was approximately 21% more likely to become a responder as a result of being treated with medication over an average of 11 weeks than if they had been given placebo (NNT = 4.85, 95% CI 3.85 to 6.25). The equivalent percentages for the individual SSRIs was 23% for paroxetine (NNT = 4.31, 95% CI 3.33 to 6.25), 22% for sertraline (NNT = 4.49, 95% CI 2.86 to 10), and 16.5% for fluoxetine (NNT = 6.07). By way of comparison, a person diagnosed with PTSD was only 7% more likely to respond to treatment with brofaromine than with placebo (NNT = 13.94, 95% CI 4.76 to 14.29).

Continued reduction of symptom severity on the CAPS was observed in the 10 week extension phase of the 12 week placebo‐controlled RCT of paroxetine (Marshall 2004). An increased rate of relapse (defined as a >= 40% increase on the eight item Treatment Outcome PTSD scale (TOP‐8) and an increase in CGI‐S score of >= 2) was observed in those patients who were randomised to placebo after responding to a 12 week trial of fluoxetine (Martenyi 2002a). Davidson (2001) additionally found that over half of the 96 outpatients who had initially responded to six months of treatment with sertraline experienced worsening of symptoms once switched over to placebo, with patients in this group being 6.35 times more likely to relapse than those participants who remained on medication. A patient was considered to have relapsed in this trial if they met all of the following criteria: an increase in CGI‐I score of at least three points, an increase in CAPS score of at least 30% and 15 points, and if the patient experienced significant clinical deterioration (as determined by the clinician).

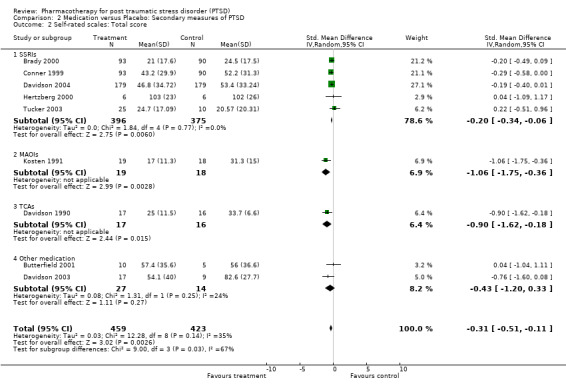

Secondary outcome measures

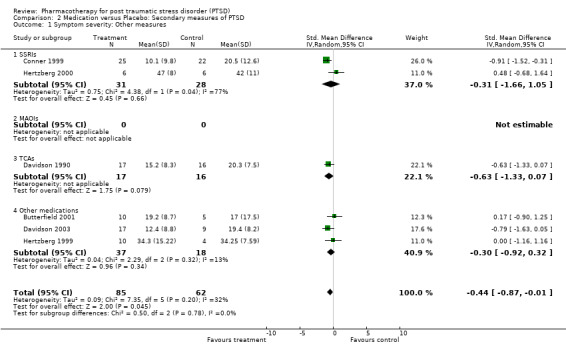

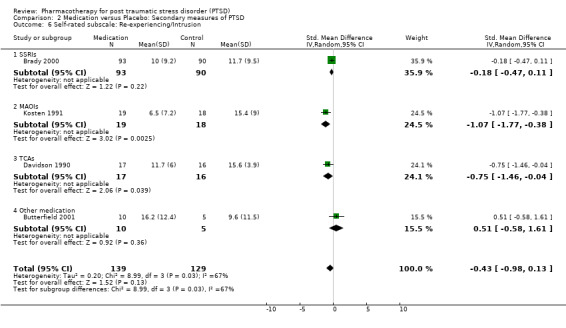

The overall symptom severity effect size for trials which did not employ the CAPS confirmed the presence of a treatment effect of medication relative to placebo (N =6, SMD ‐0.44, 95% CI ‐0.87 to ‐0.01, N = 147). Consistent results were also observed for the total scores of the self‐rated scales (IES and DTS), in which medication reduced symptom severity by ‐0.31 standard deviation units compared to placebo (N = 9, 95% CI ‐0.51 to ‐0.11, N = 882). A significant effect of medication treatment was observed for the SSRIs (SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.34 to ‐0.06, N = 769), the RCT of the MAOI phenelzine (SMD ‐1.06, 95% CI ‐1.75 to ‐0.36, N = 37), as well as for the TCA amitryptiline (SMD ‐0.9, 95% CI ‐1.62 to ‐0.18, N = 33), while no such effect was found for either of the single olanzapine and nefazodone trials.

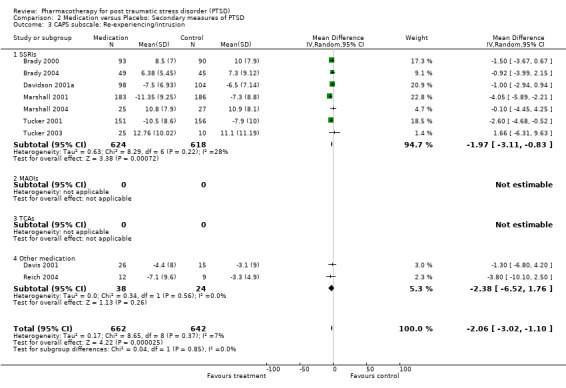

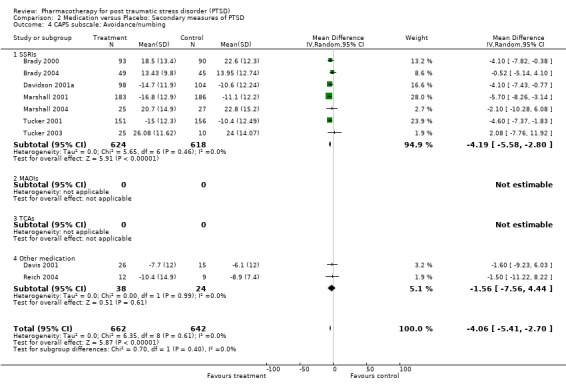

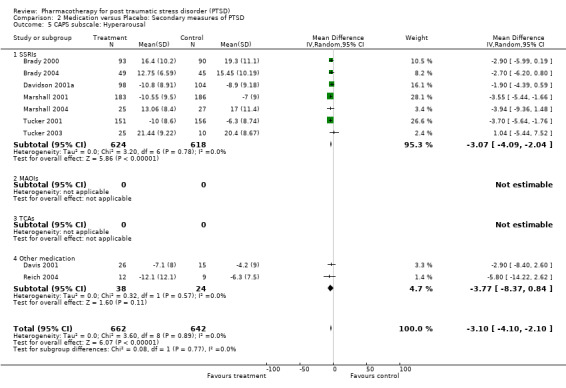

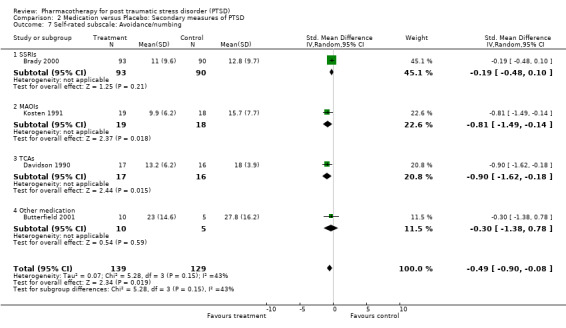

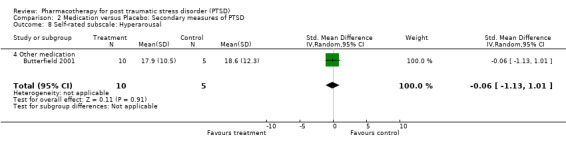

The significantly reduced scores on the re‐experiencing/intrusion (N = 9, WMD ‐2.06, 95% CI ‐3.02 to ‐1.1, N = 1304), avoidance/numbing (N = 9, WMD ‐4.06, 95% CI ‐5.41 to ‐2.7, N = 1304), and hyperarousal (N = 9, WMD ‐3.1, 95% CI ‐4.1 to ‐2.1, N = 1304) subscales of the CAPS indicates that the efficacy of medication is not limited to particular symptom clusters. The positive findings for the nine trials which provided summary statistics on these subscales was primarily attributable to the seven SSRI trials, which together contributed an average of 95% to the magnitude of the overall effect sizes on these subscales. The remaining trials of nefazodone and risperidone provided no evidence of efficacy on any of the symptom clusters measured by the CAPS. Symptoms of avoidance/numbing (N = 4, SMD ‐0.49, 95% CI ‐0.9 to ‐0.08, N = 268) but not re‐experiencing/intrusion (N = 4, SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.98 to 0.13, N = 268) were reduced after treatment according to the subscales of the self‐rated scales.

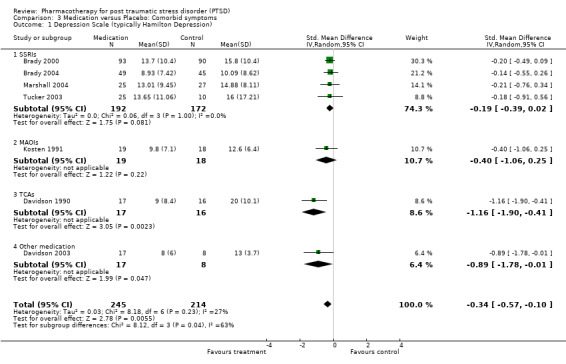

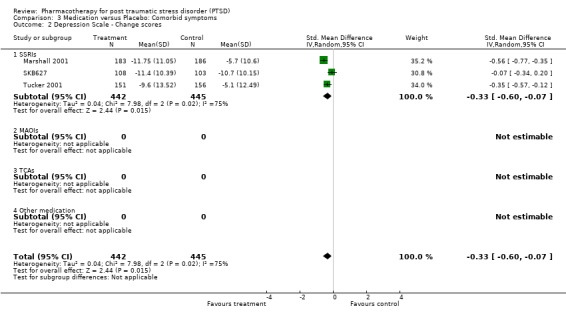

With regards to comorbidity, medication demonstrated greater efficacy in alleviating the symptoms of depression than placebo, as assessed by a range of depression scales. This was true for both trials which reported mean endpoint scale ratings (N = 7, SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.57 to ‐0.10, N = 459), as well as for the RCTs which only reported change scores (N= 3, SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.6 tp ‐0.07, N = 887). The finding that SSRIs were more effective than placebo in the trials reporting change scores, but not in those which provided endpoint summary scores (N = 4, SMD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.02, N = 364) could be attributed to less variability in the former comparison, as it only included a single medication agent (paroxetine). The increased precision of effect size estimates when change scores are used, and the greater sample size and associated power of this comparison are also likely causes of this discrepancy.

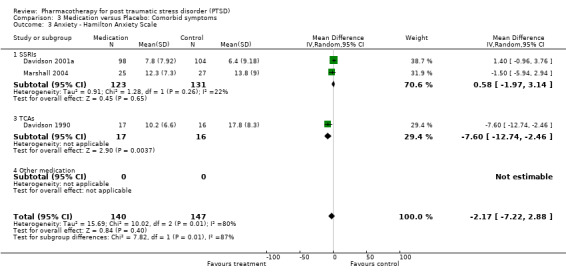

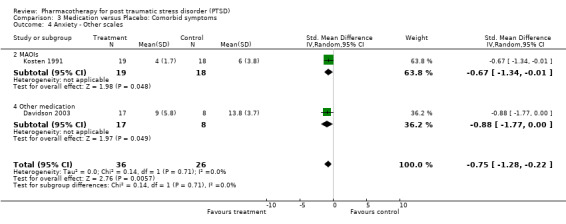

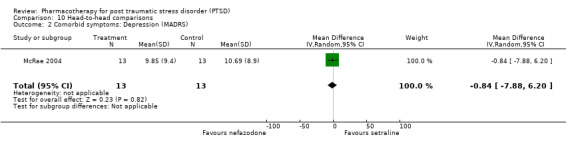

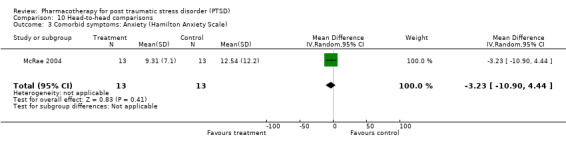

The observation that anxiety symptoms were not noticeably reduced by medication interventions, as assessed by the HAM‐A (N =3, WMD ‐2.17, 95% CI ‐7.22 to 2.88, N = 287), is largely a reflection of the lack of evidence for the efficacy of the SSRIs (N = 2, WMD 0.58, 95% CI ‐1.97 to 3.14, N = 254), with single trials of other medications demonstrating efficacy on the HAM‐A (amitryptiline) and on other anxiety scales (phenelzine). The only head‐to‐head comparison of nefazodone with sertraline for which comorbidity summary statistics were available demonstrated that these medications were equally effective in reducing symptoms of depression (WMD ‐0.84, 95% CI ‐7.88 to 6.20, N = 26) and of anxiety (WMD ‐3.23, 95% CI ‐10.9 to 4.44, N =26). No difference in the efficacy of mirtazapine and sertraline in reducing symptoms of depression on the HAM‐D was reported for the one trial which compared these medications.

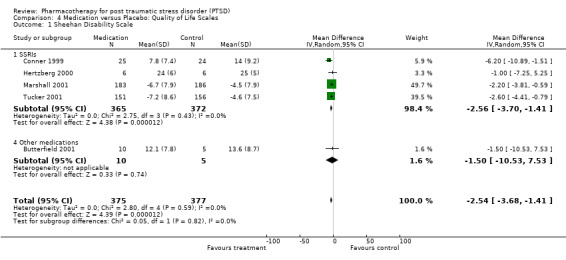

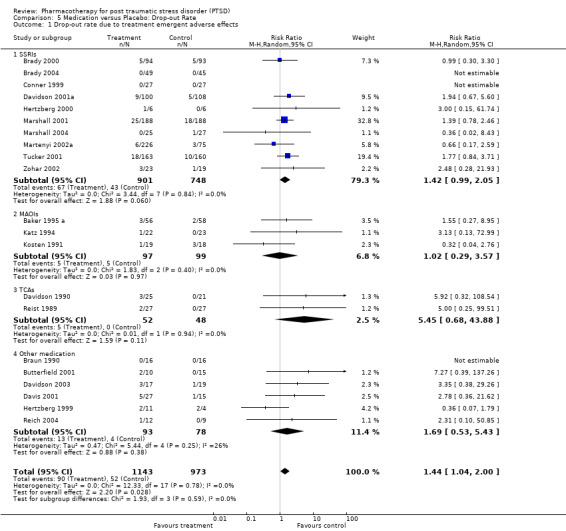

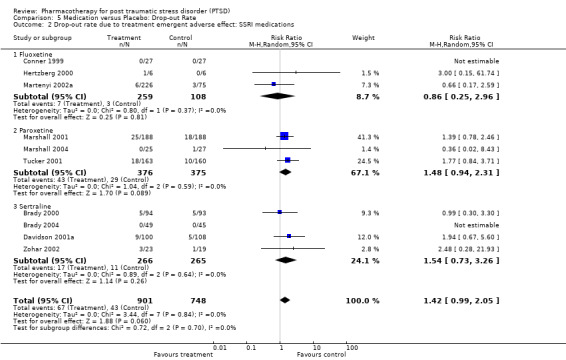

Quality of life was significantly improved by pharmacotherapy (N = 5, WMD ‐2.54, 95% CI ‐3.68 to ‐1.41, N = 752), according to summary statistics on the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). This was primarily due to the SSRI interventions (WMD ‐2.56, 95% CI ‐3.7 to ‐1.41, N = 737), with only one of the four trials in this class not demonstrably superior to placebo in improving functioning according to this measure of social, work and family‐related functioning. Patients receiving medication were more likely to withdraw from treatment due to side‐effects experienced than those who received placebo (N = 21, RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.04 to 2, N = 2116). Nevertheless, the overall effect sizes for each of the medication classes reveals that the administration of medication in the 10 SSRI (N = 1649), three MAOI (N = 196) and two TCA (N = 100) trials did not result in a significantly greater number of withdrawals due to side effects than administering placebo (although the SSRIs come close (RR = 1.42, 95%CI = 0.99, 2.05 )). The same observation was made with respect to the individual SSRI agents. In addition, the overlap between confidence intervals reveals no differences in tolerability for either the medication classes or the SSRIs. Although Saygin (2002) found that nefazodone resulted in significantly higher side‐effect scores than sertraline on the CGI, no differences in tolerability between these medications was observed by McRae (2004). A significantly larger proportion of patients (8 out of 13) who were randomised to the venlafaxine arm of a small unblinded multi‐arm RCT dropped out due to adverse events (Smajkic 2001) than those patients randomised to either the sertraline or paroxetine arms of this trial.

Heterogeneity With regards to the overall heterogeneity of trial results, the chi squared test revealed a similar degree of variation between the outcomes of trials for both treatment response and symptom severity (Chi = 16.3, P = 0.18, df = 12 and Chi = 22.04, P = 0.14, df = 16, respectively). The same finding was made across all of the secondary outcome measures employed, with the exception of the scores on the HAM‐A (Chi = 10, P = 0.007), where amitryptiline demonstrated superiority over the two SSRI trials in reducing anxiety on this scale, relative to placebo. No differences were observed in the reduction of symptom severity between the SSRI and MAOIs trials (Qb = 0.06, P =0.81, df = 14), while extensive overlap between the confidence intervals for all of the medication classes on the CGI‐I indicated little difference in terms of the proportion of non‐responders in these groups. The separation of the effects of the SSRIs by agent revealed that paroxetine was more effective in reducing symptom severity than sertraline (Qb = 8.86, P < 0.01). Indeed, the reduction of symptom severity was nearly twice as large for paroxetine as for all the medications combined (WMD ‐10.49 versus ‐5.76). Nevertheless, no such differences in the efficacy of any of the SSRI medications was observed for treatment response. There were too few trials on the secondary outcomes to determine relative efficacy of different medication classes.

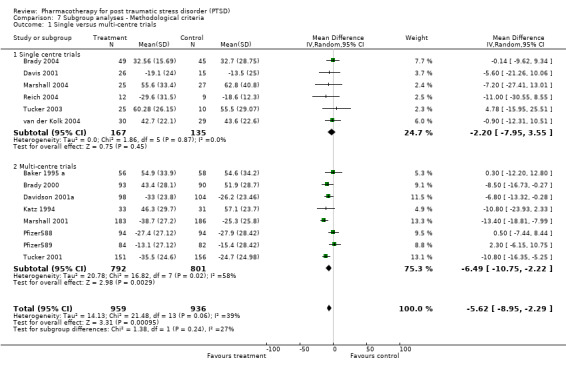

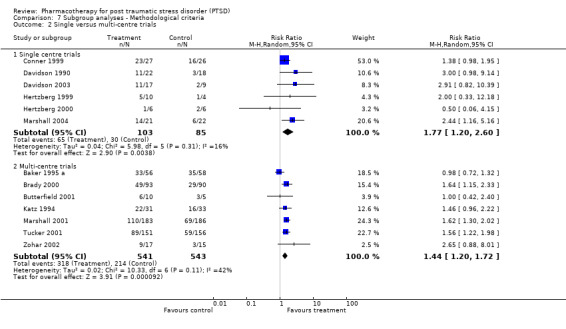

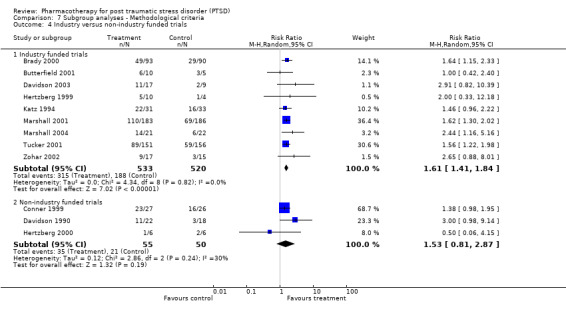

Subgroup analyses Symptom severity in the six trials which took place across multiple centres for which the CAPS total score was available was reduced to a greater extent than the eight trials conducted within single centres (Qb = 2.8, P = 0.09, df = 13). However, this effect was not observed in the analysis of treatment response (N = 13; 95% CI for single centre trials 1.2 to 2.6, N =188; 95% CI for multi‐centre trials 1.2 to 1.72, N = 1084). No difference in treatment response was evident in the comparison of industry funded trials versus non‐industry funded trials either, as the confidence interval of the effect size for the former (N = 9, 95% CI 1.41 to 1.84, N = 1053) was contained within the confidence interval of the latter (N = 3, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.87, N = 105).

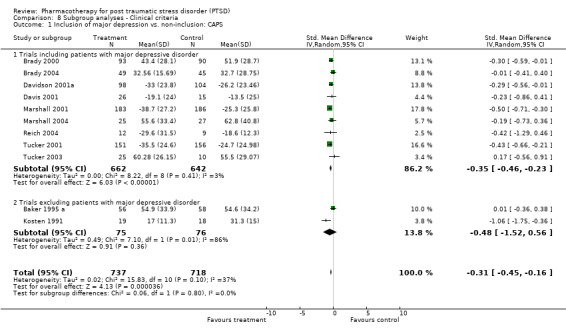

Symptom severity decreased to an equivalent extent (Qb = 0.5, P = 0.48) in trials which included depressed participants (N = 9, SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.23, N = 1304) as in those which did not (N = 2, SMD ‐0.48, 95% CI ‐1.52 to 0.56, N = 151). RCTs which contained few combat veterans (N = 8, average proportion of war veterans = 3%) demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in symptom severity following medication treatment (Qb = 4.12, P = 0.04) than trials with a large percentage of participants with combat‐related trauma (N = 4, average proportion = 61.1%). The difference between these groups was not detected with respect to treatment response, however, as evidenced by the inclusion of the confidence interval for the latter group (N = 5, average proportion = 3.8%) within the confidence interval of the former (N = 8, average proportion = 56%).

The finding of a difference in the reduction of symptom severity between trials with few war veterans versus those with many was not surprising, given the general characterisation of the war trauma subgroup of PTSD sufferers as more treatment resistant than other subgroups. War veteran samples are typically predominantly male (86.7% versus 32.8% in the groups compared in this review), and have more severe (84.9 versus 74.6 points on the CAPS) and chronic (21.1 years versus 10.9 years) PTSD than those trials composed of patients with other types of trauma. In addition, although it was not possible to observe differences in treatment response for these two group, four of the five trials with fewer war veterans demonstrated superior treatment response amongst participants given medication, as compared to none of the eight trials with a substantial proportion of veterans.

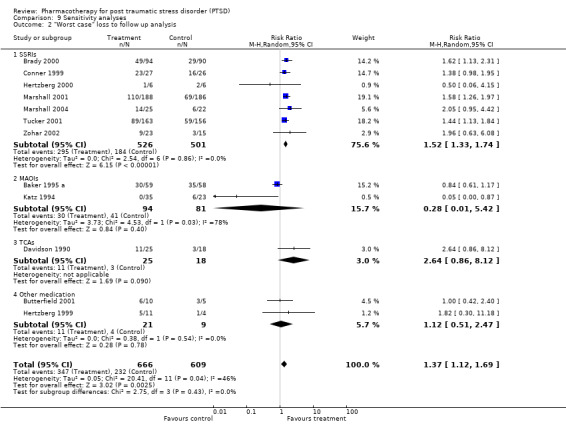

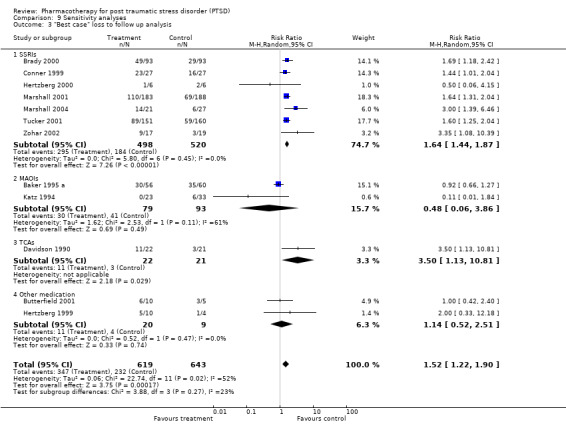

Sensitivity analyses

The comparison of the analysis of treatment efficacy in terms of treatment non‐response as opposed to response on the CGI‐I (or equivalent) revealed similar outcomes for both the overall short‐term efficacy of medication (N = 13, RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.74, N = 1272), as well as the efficacy of the SSRIs in treating PTSD (N = 7, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.74, N = 999). However, whereas the use of treatment response as a summary statistic indicated that both the TCA amitryptyline and the novel antidepressant mirtazapine were no more effective than placebo, relative risk of non‐response to treatment provides evidence that both of these medications are more effective over the short‐term than placebo (mirtazapine: RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.94, N = 26; amitryptyline: RR 0.6, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.96, N = 40). It seems probable that the failure to find a significant effect for these two agents on treatment response reflects the lack of sensitivity of the relative risk of benefit for therapeutic trials to the effects of interventions when the placebo response rate is low (Deeks 2002), as was the case for these two trials. The number of participants responding to medication was significantly higher relative to the placebo control in both the worst case scenario (N = 12, RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.69, N = 1275), where those participants from the medication group who were not included in the analysis were regarded as non‐responders, and in the best case scenario (N = 12, RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.9, N = 1262), in which those participants excluded from the placebo control were regarded as non‐responders. The overlap in the confidence intervals for these two outcomes indicates that loss to follow up is unlikely to have influenced assumptions made about the overall efficacy of medication.

Publication bias

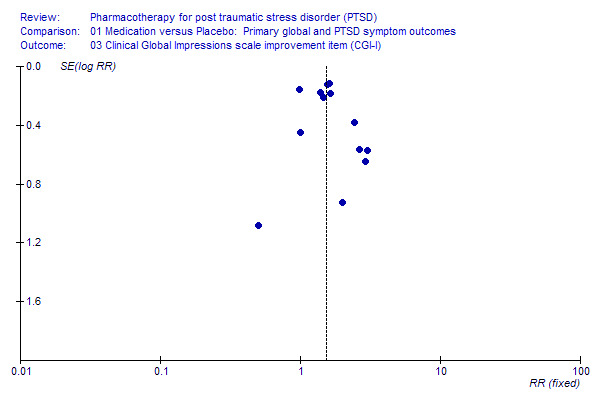

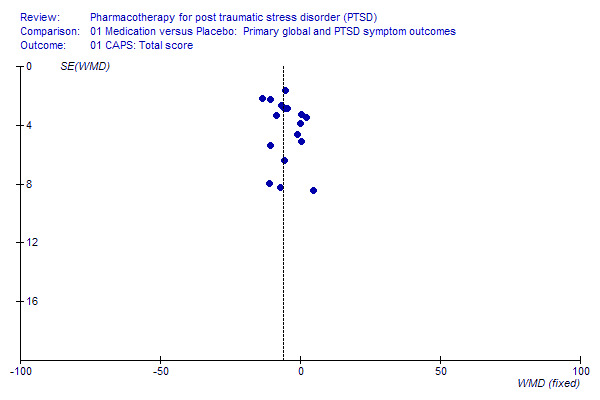

The distribution of trials on a funnel plot for treatment response (see Additional Figures: Figure 1) provides no evidence of substantial publication bias. A slight skewness in the distribution of trials on the funnel plot for the CAPS (see Additional Figures: Figure 2) could be interpreted as evidence of a tendency for trials with larger standard errors and smaller effect sizes to go unreported.

1.

Publication Bias 2.

Funnel plot of publication bias on Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ Improvement item (CGI‐S)

2.

Publication Bias 1.

Funnel Plot of publication bias on Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

Discussion

This review provides evidence of the efficacy of medication in the short‐term treatment of PTSD, as assessed on the primary outcome measures of responder status and symptom severity. Medication was significantly more effective than placebo across the three symptom clusters which characterize PTSD (re‐experiencing/intrusion, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal) as assessed by the CAPS subscales. Scores on the self‐rated symptom severity scales confirmed medications' effectiveness in reducing overall symptom severity, as well as PTSD avoidance symptoms. In addition, the administration of medication resulted in a reduction in comorbid symptoms, and the improvement in quality of life measures. These findings hold despite the clinical heterogeneity of PTSD subjects included in the reviewed trials (see Table 1 ‐ Characteristics of Included Studies). Although a recent guideline noted that, with few exceptions, the overall effect size for medication trials of PTSD failed to exceed the limit of 0.5 defined as indicative of clinical effectiveness (NICE 2005), we would caution that there is no direct translation between the effect size statistic and assessments of clinical effectiveness. The findings here that the CGI‐I response rate was 59.1% on medication and 38.5% on placebo, and of a relatively low NNT of 4.85, support the growing clinical consensus that medication does have an important role in the treatment of PTSD.

The current evidence base of RCTs is unable to demonstrate superior efficacy or acceptability for any particular medication class. Although some have suggested that the SSRIs are more effective than older antidepressants (Dow 1997; Penava 1996), class membership did not contribute significantly to the variation observed in symptom severity outcomes between trials, while the confidence intervals for the summary statistic of responder status on the seven SSRI trials overlapped with that of the MAOI and TCA trials. Similarly, direct comparisons of sertraline and nefazodone demonstrated that these medications were equally effective in reducing PTSD symptom severity. Although the SSRIs have often been said to have superior tolerability in comparison to older medication classes, this was not readily apparent on analysis of drop‐out rates due to treatment emergent side‐effects in medication versus placebo groups. However, it should be emphasized that drop‐out rates due to adverse events may not always provide an accurate measure of medication tolerability (Loke 2005). In addition, it is important to be aware of the need for careful monitoring after initiation of SSRIs (CSM 2004). Nevertheless, the SSRI trials constitute the bulk of the evidence for the efficacy of medication in treating PTSD, both in terms of the number of studies and their size. The finding of the effectiveness of the SSRIs were also more robust to differences in the particular summary statistic employed than was the case for either the amitryptiline or mirtazapine trials. It is therefore reasonable to support the expert consensus (Foa 1999; Ballenger 2000; Ballenger 2004) that SSRIs constitute the first line medication choice in PTSD.

Nevertheless, the efficacy of medication in PTSD is unlikely to extend to all medications. While there is preliminary evidence that paroxetine is more effective than sertraline in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms, and although the two mirtazapine trials provide some support for the efficacy of this agent, neither of the brofaromine, olanzapine and lamotrigine trials demonstrated efficacy with regards to treatment response or symptom reduction. Given the lack of a placebo control in two of the RCTs of nefazadone, and the negative finding with regards to symptom reduction in the third, evidence of the efficacy of this medication must be regarded as inconclusive. The failure to detect an effect of medication in the olanzapine and lamotrigine trials, despite other open‐label evidence that olanzapine is effective in combating PTSD (Petty 2001;Pivac 2004), may, however, be attributable to the small samples employed (average number = 15). Similarly, the failure of amitriptyline to alleviate the symptoms of PTSD in the only trial of this medication can perhaps be explained by the short duration of the trial (four weeks). Methodological limitations in the form of small sample size and short duration might also account for the negative findings of the crossover trials of alprazolam, inositol, desipramine, and phenelzine. This possibility is supported by the finding of reduced symptom severity in the only other controlled trial of phenelzine (Kosten 1991). Nevertheless, the lack of efficacy of desipramine could arguably support the (at this stage speculative) hypothesis that more noradrenergic agents (such as desipramine) are less useful than more serotonergic agents in PTSD (Dow 1997; Penava 1996). The question of whether benzodiazepines are useful immediately after trauma (Gelpin 1996; Mellman 1998) or in PTSD remains debated, although recent expert consensus panels have suggested caution (Foa 1999; Ballenger 2000; Ballenger 2004) in the use of these agents. Neither the potential clinical (presence of combat trauma, comorbid depression) or methodological (single versus multi‐centre trials, industry versus non‐industry funding) predictors of medication response tested in this review can account for the substantial proportion (41%) of patients who do not appear to respond to medication. The finding that symptom severity is reduced to a greater extent in the multi‐centre than the single centre trials should be interpreted with caution, not only due to the marginal significance of this finding, but also because it was not possible to replicate this finding with regards to treatment response. The failure to detect an association between the presence of participants with comorbid major depression and treatment efficacy indicates that medications are unlikely to exert their effects in PTSD indirectly via a reduction in depressive symptoms.

This review found some evidence that war veterans are more resistant to pharmacotherapy than other patient groups, at least with regards to the reduction of symptom severity. This was despite the fact that a number of RCTs with war veteran samples were excluded from this review (Hamner 1997; Hamner 2003; Stein 2002; Monnelly 2003; Raskind 2003; Bartzokis 2005) (see Table 2 ‐ Characteristics of Excluded Studies), and that it was not possible to classify certain large‐scale unpublished trials according to trauma type (Davidson 2004; Eli Lilly 2006; SKB627). Further research is therefore required to determine conclusively whether being a war veteran is a significant predictor of treatment response, and to distinguish the effects of this trauma subtype from other potential predictors of treatment response with which it is associated (such as being male, and having more chronic and severe PTSD). It is possible that the crucial factor is not so much being a war veteran, but rather being a veteran of particular wars (Zohar 2002). Given the heterogeneous phenomenology of PTSD, it remains crucial to determine the factors which do predict response to medication, and also to delineate whether certain medications are more effective for particular symptom sets (including symptoms such as psychosis (Hamner 1996), dissociation (Fichtner 1990; Marshall 1998b) and vulnerability to stress (Connor 1999)). Future RCTs and meta‐analyses should attempt to address such questions in greater detail.

The importance of long‐term treatment of PTSD is indicated by the observation of a continued improvement of PTSD symptoms following acute treatment with paroxetine but not placebo (Marshall 2004). The conclusion that a short‐term course of treatment with SSRIs may be inadequate is supported by increased relapse rates in trials of both fluoxetine (Martenyi 2002b) and sertraline (Davidson 2001b). The findings of these trials are consistent with consensus recommendations of six to twelve months medication treatment for acute PTSD (Foa 1999), and interventions of at least 12 months to prevent relapse in the treatment of chronic PTSD (Foa 1999; Ballenger 2000; Ballenger 2004). Although the current review does not directly address the question of whether medication or psychotherapy exerts a larger effect in PTSD (van Etten 1998), combined treatment is often used in clinical settings, and this may contribute to the effects of psychotherapy in published studies. Conversely, it has been speculated that the high placebo response rate observed in some of the trials included in this review (Brady 2000; van der Kolk 2004) might be the consequence of psychological support provided to the patients as an inadvertent consequence of participating in the rigorous assessment procedures implemented within the trials (Krakow 2000; van der Kolk 2004). Nevertheless, in one of the trials for which this suggestion was made (van der Kolk 2004), the authors still discovered psychotherapy (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)) to be more effective than fluoxetine in maintaining the complete remission of PTSD symptoms six months after the end of a eight week placebo‐controlled RCT. There are, however, few direct comparisons of the efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for PTSD, and given that few psychotherapy RCTs have masked treatment assignment (NICE 2005) indirect comparisons of effect sizes may also have limited utility. Theoretically, modern understanding of PTSD as involving psychobiological dysfunctions would indicate that it is unnecessary to institute false dichotomies between brain and mind, and that both kinds of intervention might be useful (Southwick 1993; Khouzam 1997). Certain medications (e.g. benzodiazepines) have, however, been argued to diminish the effects of psychotherapy, so rigorous comparative studies are needed.

Additional questions for future pharmacological research in the area of PTSD include the effectiveness of medication in clinical settings, and the precise effects of medication on quality of life measures (Fossey 1994; Rapaport 2002). Further research on medication in PTSD in different age samples (Famularo 1988; Looff 1995; Harmon 1996; Horrigan 1996; Seedat 2001), on patients with comorbid substance use disorders (Liebowitz 1989; Brady 1995; Brady 2004), and on more treatment‐refractory (Braun 1990; Demartino 1995; Hamner 1997; Hamner 1998; Hidalgo 1999; Stein 2002; Raskind 2003; Bartzokis 2005) or non‐compliant (Kroll 1990) patients is also needed. In addition, randomised controlled trials are needed to determine the efficacy of promising medications, such as tiagabine (Taylor 2003), tianeptine (Onder 2005) and topirimate (Berlant 2002; Berlant 2004), for which only open‐label trials have been conducted thus far.

Given the high prevalence and enormous personal and societal costs of PTSD, there are still relatively few RCTs of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. No controlled trials were found in paediatric or geriatric subjects. With few exceptions (Baker 1995 a; Reist 1989; Braun 1990; Davidson 1990; Hertzberg 1999; Hertzberg 2000; Brady 2004), trials have excluded patients with comorbid substance use. One such exception to be included in this review was a RCT of sertraline in treating concurrent PTSD and alcoholism (Brady 2004), in which little difference was found in the efficacy of medication versus placebo in reducing symptom severity. Also, although outside the scope of the current review, there seem to be few RCTS of the treatment of traumatised patients prior to their meeting criteria for PTSD (Robert 1999; Pitman 2002; Mellman 2002; Schelling 2004), a potentially important clinical area.

Finally, the inherent problems of meta‐analysis should also be borne in mind (Bailar 1997); certainly these are by no means a substitute for clinical research. This is especially the case when there is evidence of the possibility that smaller trials with negative outcomes are not being published. Furthermore, the context of clinical practice differs from controlled trials in many respects, not the least being the inclusion of more complex patients (including patients with possible "secondary gain" from symptoms, a group that has been specifically excluded from more recent RCTs (Brady 2000)) and the possible need for polypharmacy in a subgroup of PTSD patients (Kolb 1984; Kinzie 1989; Burdon 1991; Hargrave 1993; Leyba 1998). Moreover, methodological shortcomings, such as failure to employ independent outcome assessors in trials which adjust medication dosage on the basis of side‐effect severity, and inadequate statistical methods of compensating for patient withdrawals, risk undermining the best efforts to minimise bias in the findings of systematic reviews of health care interventions. However, an advantage of the Cochrane Collaboration is that it encourages regular updating of reviews in the light of new data, and hopefully additional data from new randomised controlled trials of medication in PTSD will become available for inclusion in a revised systematic review in the future. Given the high prevalence of PTSD, its chronicity and morbidity, and its enormous personal and societal costs, additional prospective research on the pharmacological prevention and treatment of this disorder is clearly required, and systematic reviews and retrospective analyses may be useful in integrating the findings of such work as well as in suggesting areas for further investigation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Medication treatments can be effective in PTSD, acting to reduce its core symptoms, and should be considered as part of the treatment of this disorder. The existing evidence base of RCTs includes a heterogenous sample of participants with a range of different traumas, trauma duration and severity, and comorbidity. Although there is also no clear evidence to show that any particular class of medication is more effective or better tolerated than any other, the greatest number of trials showing efficacy to date, as well as the largest, have been with the SSRIs. In contrast, there have been negative studies of benzodiazepines, MAOIs, anti‐psychotics, lamotrigine and inositol. In addition, although there was only one RCT in which psychotherapy was compared with pharmacotherapy, from a clinical perspective it is as well to remember the possible value of this modality alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy. The findings of maintenance trials support the value of long‐term interventions in increasing the efficacy of medication and preventing relapse.

Implications for research.

Given the prevalence and costs of PTSD, there is a need for further controlled clinical trials in the treatment of this disorder. The differential efficacy and acceptability of different classes of medication, including newer agents potentially useful in this disorder (e.g. escitalopram, tiagabine, tianeptine, tropirimate), requires study. Questions for future research also include the precise effects of medication on quality of life measures, appropriate dose and duration of medication, and determining factors which predict response to medication. Further research on the value of medication in PTSD in different trauma groups, in paediatric and geriatric subjects, in patients with comorbid substance use, and in treatment‐refractory patients is needed. Clinical trials to determine the possible benefits of early (prophylactic), combined (with psychotherapy), and long‐term (maintenance) intervention in PTSD may also be valuable.

Feedback

Comments submitted by Danielle Stacey, 8 December 2015

Summary

In 2009, Stein DJ et al. published a Cochrane review which provided us with a very thorough explanation of the literature surrounding pharmacotherapy for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1 After a thorough review of the publication, we have a few enquiries regarding the patient population represented in the meta‐analysis and the statistical analysis conducted. In addition, we have provided some potential recommendations for future updates.

Clinical heterogeneity