Climate change and malnutrition in all its forms, including obesity and undernutrition, constitute two of the greatest threats to planetary and human health. As recently described (1), obesity and undernutrition each affect approximately 2 billion people worldwide, and in 2017, over 150 million children were stunted. The costs of obesity account for almost 3% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), and the costs of undernutrition in Asia and Africa range from 4% to 11% of GDP (1). The costs of unmitigated climate change, which will disproportionately affect low-income countries, may exceed 7% of the world and 10% of the US GDP by 2100 (2).

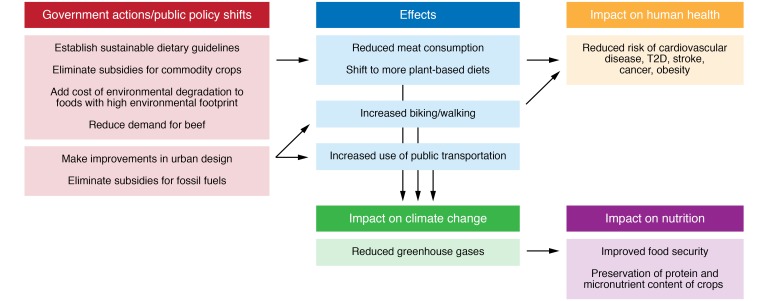

The future of our health and that of our planet depend on our ability to massively reduce our contribution to climate change, and we have a limited amount of time in which to do so. No single solution will suffice. Nonetheless, changes in the food, agriculture, and transport systems can mitigate climate change and reduce obesity, undernutrition, cardiovascular disease, and colon cancer (Figure 1). We know some steps that can be taken, but how to overcome policy resistance and inertia is the challenge.

Figure 1. Strategies to mitigate the global syndemic.

There are several triple-duty solutions to the global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change. Solutions include elimination of subsidies for commodity crops, which will increase the price of beef, reduce demand, decrease beef production, and prevent obesity, colon cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Reduced beef production will also reduce the generation of greenhouse gases (GHGs), which will preserve the nutrient content of crops and reduce food insecurity. Changes in urban design to reduce car use and increase physical and public transport will increase physical activity, prevent obesity, and reduce GHGs. However, these scenarios are disruptive and have already encountered political inertia and strenuous resistance by powerful vested industries. The foundation for federal policy change must begin locally with awareness of the links between our current dietary and activity practices and build from individual behavioral change to changes in our hospitals, schools, and municipal governments. Urgent action is required now to preserve human and planetary health.

Interacting pandemics

The pandemics of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change constitute a syndemic (3): they interact in time and place, have synergistic adverse effects on each other, and importantly, share common underlying social or economic determinants and policy drivers. These three pandemics are driven by the underlying systems of agriculture and food production, urban design, land use, and transport. For example, methane is a particularly potent GHG. The methane produced by cattle to meet the demands for meat consumption is associated with environmental degradation and generates approximately 9% of increased GHGs in the United States (4), and beef consumption is associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, and colon cancer. Additionally, urban design and land use patterns foster reliance on car use, which leads to obesity by displacing physical transport, like biking and walking, and generates approximately 29% of GHGs in the United States (4). Food waste in the United States has been estimated to account for almost 1 pound of food per day and to generate 8% of global GHG emissions (5). Also of note, the global warming caused by increased GHG production increases catastrophic weather events and reduces protein and micronutrients in crops (6, 7), all of which contribute to food insecurity and undernutrition in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In turn, low birthweight in LMICs may be associated with later obesity, and over 10% of children in LMICs are stunted and have obesity (8). The advantage of the syndemic perspective is that it offers triple-duty solutions. For example, reduced meat consumption will improve human health, reduce GHG emissions, and in the longer term, reduce food insecurity in LMICs.

Dietary recommendations addressing health and climate change

The United States bears a major obligation to address climate change. We rank second in the world in CO2 emissions and fourth behind mainland China, India, and Brazil in terms of our per capita diet-related GHG footprint (9). Therefore, the changes we make in our food, agriculture, and transport systems can play a significant role in the reduction of our GHG generation and its contribution to climate change. Because the effects of these changes are context specific (10), I will focus on their impact in the United States.

Meat production as practiced today is the single largest contributor to GHGs from agriculture. Compared with the average US diet, diets lower in meat, such as the Mediterranean diet, have been estimated to decrease GHGs by 72%, land use by 58%, and energy consumption by 52% (11, 12). These and other observations were incorporated into the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Advisory Committee (DGAC) report, which concluded that “Consistent evidence indicates that, in general, a dietary pattern that is higher in plant-based foods, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, and lower in animal-based foods is more health promoting and is associated with lesser environmental impact (GHG and energy, land, and water use) than is the current average US diet” (13, 14).

Similar recommendations for sustainable diets were made by the EAT–Lancet Commission (15). Diets with reduced meat intake, such as the Mediterranean and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diets, not only are better for the planet but also improve health. The Mediterranean diet was associated with decreased severe cardiovascular events among individuals with significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease (16), and the DASH diet was associated with decreased all-cause mortality in adults with hypertension (17). Estimates suggest that plant-based diets could reduce mortality from the diet-related diseases of stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and cancer by 6%–10% and reduce diet-related GHGs by 29%–70% by 2050 compared with a reference diet (18).

Reductions in GHGs and cost savings from reductions from the four diet-related diseases increase as diets are increasingly plant based. The majority of these benefits are attributable to reductions in meat intake. Shifts from cars to public transport, biking, and walking will have a similar impact on reducing chronic diseases like obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, as well as reducing GHG emissions.

Adoption of the DGAC’s recommendation that sustainability be incorporated into the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) would have instituted sustainable dietary practices in federal policy. However, the recommendation was met with vigorous opposition from the beef industry, and that opposition led the secretaries of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture to announce that sustainability was outside the scope of the DGAs (19). As a result, the recommendation was stripped from the final version of the DGAs. Given the need for behavioral and policy change to mitigate the production of GHGs from the food and agriculture systems and improve human and planetary health, the secretaries’ decision was the modern equivalent of Nero fiddling as Rome burned, only in this case, it will be the planet that suffers.

Now is the time for action

Because we have a limited amount of time in which to mitigate climate change, radical strategies are required. For example, elimination of subsidies for commodity crops and fossil fuels, along with adding the costs of environmental degradation to the price of beef, other GHG-intensive foods, and fossil fuels will reflect their true costs. Increased costs will reduce beef intake, move consumption to more plant-based diets, and increase public transport, walking, and biking. In many places, the shifts in transport will need to be accompanied by long overdue shifts in community infrastructure. However, the lack of political will to make the necessary radical changes is reflected in the federal response to the dietary guidelines, the policy resistance of the meat and fossil fuel industries, and the denial of the US responsibility for climate change at the highest levels of our government.

The absence of widespread public awareness and outrage in response to the secretaries’ decision emphasizes the need to build a greater base of grassroots support for policies that promote sustainable dietary practices and changes in physical transport. To generate political will, we must empower individuals to recognize that they can make a difference. That difference should begin with changes in our own diets and transportation patterns, and then we should extend these efforts to our families, institutions, and communities.

In addition to individual efforts, the health care sector is a logical target for the promotion of plant-based diets and efforts to reduce the sector’s contribution to climate change. The health care sector contributes an estimated 4%–8% of our country’s GHGs (20, 21). In 2019, the American Medical Association and over 100 other organizations signed a call to action (CTA) to address climate change and health (22). More than half of the health sector’s emissions are attributable to energy use. The incorporation of climate solutions into health care and all public health systems was one of 10 priority actions the CTA recommended.

Strategies that improve the health of the planet and the health of our employees include subsidizing employees for the use of mass transit, using procurement policies to provide sustainably produced foods in our cafeterias, and increasing the price of foods with high environmental footprints to discourage their consumption. Model programs include Kaiser Permanente’s 2016 pledge to remove more carbon than their organization emits by 2025 by utilizing clean energy, purchasing sustainably produced foods, moving zero food waste to landfills, and recycling, reusing, or composting 100% of their nonhazardous waste (23).

A 2018 Gallup poll showed that 70% of respondents aged 18–34 are worried “a great deal/fair amount about global warming” compared to 56% of those 55 years or older (24). Millennials and Gen Z members should mobilize and advocate in their colleges, universities, and work sites for changes in procurement policies, for labeling sustainably produced foods, and for food waste recycling. Many of these strategies are already being employed at the municipal level through programs such as the American Cities Climate Challenge (ACCC) funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies (25). The 25 ACCC cities’ goals are to reduce emissions from buildings, transportation, and food waste.

Concluding remarks

One of the more sobering conclusions is that multiple interventions directed at the food system will not likely achieve the goal of reducing the rise in mean surface temperature by 2°C by 2050 (18). Furthermore, dietary interventions will reduce but not eliminate increases in GHGs. A relevant analogy is that of a bathtub filling with CO2. The bathtub of CO2 is nearly full, and unless the drainage from the bathtub increases, it will overflow (26). One of the most important agricultural sinks is sustainable land use. Regenerating and reforesting the land freed by the reduced demand for beef will contribute to carbon sequestration, but unless we also replace our reliance on fossil fuels by changing the energy use of buildings and transportation systems, the outlook is grim. Hopeful developments include growing interest in vegetarian diets, meat alternatives, the rapid growth in sales of sustainably produced and better-for-you products, and the participation by youth in demonstrations to protest climate change. Will these unconnected efforts transform to a unified social movement? Only time will tell.

Version 1. 01/06/2020

Electronic publication

Version 2. 02/03/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author declares grant support from Novo Nordisk and the Kresge Foundation and consulting work for the National Academy of Medicine Roundtable on Obesity Solutions and the Weight Watchers Adolescent Advisory Group and is on the board of directors for the Partnership for a Healthier America and the JPB Foundation.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):556–558. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI135004.

References

- 1.Swinburn BA, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kahn ME, Mohaddes K, Ng RNC, Pasaran MH, Raissi M, Yang J-C. Long-Term Macroeconomic Effects of Climate Change: A Cross-Country Analysis. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26167 August 2019. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 3.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Environmental Protection Agency. Sources of Green House Emissions. Environmental Protection Agency Website. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 5. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Wastage Footprint and Climate Change. Food and Agriculture Organization Website. http://www.fao.org/3/a-bb144e.pdf Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 6.Loladze I. Hidden shift of the ionome of plants exposed to elevated CO2 depletes minerals at the base of human nutrition. Elife. 2014;3:e02245. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers SS, et al. Increasing CO2 threatens human nutrition. Nature. 2014;510(7503):139–142. doi: 10.1038/nature13179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzioumis E, Kay MC, Bentley ME, Adair LS. Prevalence and trends in the childhood dual burden of malnutrition in low- and middle-income countries, 1990-2012. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(8):1375–1388. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016000276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim BF, et al. , Nachman KE. Country-specific dietary shifts to mitigate climate water crises. Glob Environ Change. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.010. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.010. [published online ahead of print August 7, 2019]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(10):e451–e461. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sáez-Almendros S, Obrador B, Bach-Faig A, Serra-Majem L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environ Health. 2013;12:118. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJ, Smith P, Haines A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0165797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/ February 2015. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 14.Nelson ME, Hamm MW, Hu FB, Abrams SA, Griffin TS. Alignment of healthy dietary patterns and environmental sustainability: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(6):1005–1025. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willett W, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estruch R, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh A, Lipsitz SR, Natarajan S. Association between a DASH-like diet and mortality in adults with hypertension: findings from a population-based follow-up study. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(4):409–416. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springmann M, Godfray HC, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(15):4146–4151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523119113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vilsack T, Burwell S. 2015 Dietary Guidelines: Giving You the Tools You Need to Make Healthy Choices. US Department of Agriculture. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2015/10/06/2015-dietary-guidelines-giving-you-tools-you-need-make-healthy-choices Posted February 21, 2017. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 20. Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, Ashby B, Steele K. Health Care’s Climate Footprint: How the Health Sector Contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action. Health Care Without Harm Website. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf September 2019. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 21.Chung JW, Meltzer DO. Estimate of the carbon footprint of the US health care sector. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1970–1972. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Climate Health Action. U.S. Call to Action on Climate, Health, and Equity: A Policy Action Agenda. Climate Health Action Website. https://climatehealthaction.org/cta/climate-health-equity-policy/ Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 23. Kaiser Permanente. Pledging Bold Envionmental Performance by 2025. Kaiser Permanente Website. https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/community-health/news/kaiser-permanente-pledges-bold-2025-environmental-performance-to Published May 17, 2016. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 24. Reinhart RJ. Global Warming Age Gap: Younger Americans Most Worried. Gallup Website. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234314/global-warming-age-gap-younger-americans-worried.aspx Published May 11, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 25. Bloomberg Philanthropies. American Cities Climate Challenge. Bloomberg Philanthropies Website. https://www.bloomberg.org/program/environment/climatechallenge/ Accessed November 20, 2019.

- 26.Sterman JD. Economics. Risk communication on climate: mental models and mass balance. Science. 2008;322(5901):532–533. doi: 10.1126/science.1162574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]