Abstract

Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 is a ubiquitously expressed kinase inhibited by insulin-dependent Akt/PKB/SGK. Mice expressing Akt/PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3α/GSK3β (gsk3KI) exhibit enhanced sympathetic nervous activity and phosphaturia with decreased bone density. Hormones participating in phosphate homeostasis include fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23, a bone-derived hormone that inhibits 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3; calcitriol) formation and phosphate reabsorption in the kidney and counteracts vascular calcification and aging. FGF23 secretion is stimulated by the sympathetic nervous system. We studied the role of GSK3-controlled sympathetic activity in FGF23 production and phosphate metabolism. Serum FGF23, 1,25(OH)2D3, and urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) were measured by ELISA, and serum and urinary phosphate and calcium were measured by photometry in gsk3KI and gsk3WT mice, before and after 1 wk of oral treatment with the β-blocker propranolol. Urinary VMA excretion, serum FGF23, and renal phosphate and calcium excretion were significantly higher, and serum 1,25(OH)2D3 and phosphate concentrations were lower in gsk3KI mice than in gsk3WT mice. Propranolol treatment decreased serum FGF23 and loss of renal calcium and phosphate and increased serum phosphate concentration in gsk3KI mice. We conclude that Akt/PKB/SGK-sensitive GSK3 inhibition participates in the regulation of FGF23 release, 1,25(OH)2D3 formation, and thus mineral metabolism, by controlling the activity of the sympathetic nervous system.—Fajol, A., Chen, H., Umbach, A. T., Quarles, L. D., Lang, F., Föller, M. Enhanced FGF23 production in mice expressing PI3K-insensitive GSK3 is normalized by β-blocker treatment.

Keywords: protein kinase B, calcitriol, propranolol, sympathetic activity

Insulin mainly regulates glucose homeostasis, but also affects renal phosphate handling (1, 2). Cellular insulin’s effects are in large part mediated by activation of PI3K resulting in the stimulation of Akt/PKB and serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) isoforms (3, 4). Upon activation, Akt/PKB (5) and SGK (6, 7) isoforms can phosphorylate numerous cellular targets, including glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3, thereby rendering this kinase inactive. Loss of Akt2 or of SGK3 activity in mouse models results in decreased renal phosphate reabsorption and, hence, phosphate loss (8, 9). Moreover, transgenic mice expressing Akt/PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3α/β [gsk-3 knockin (gsk-3KI)] have hypophosphatemia, phosphaturia, and decreased bone density, illustrating the significance of PI3K signaling for renal phosphate handling (10). A direct inhibitory effect of GSK3 on renal sodium-dependent phosphate transporter IIa (NaPiIIa) (10) is likely to contribute to the phosphaturia of gsk-3KI mice, but may not fully explain it. Gsk-3KI mice also have hypertension and a faster heart rate caused by enhanced sympathetic activity (11).

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 is a bone-derived hormone that controls phosphate and calcium metabolism (12–14). Its main target is the kidney, where FGF23 inhibits tubular phosphate but fosters tubular calcium reabsorption (14–21). Renal expression of FGF23 is observed in polycystic kidneys (22). Moreover, FGF23 has been shown to inhibit renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1α-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) and to stimulate 25-hydroxyvitamin D 24-hydroxylase (Cyp24a1) thereby suppressing the formation and favoring the catabolism of the biologically active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3; calcitriol) (20, 23–25). Therefore, FGF23 lowers the plasma level of both 1,25(OH)2D3 and phosphate.

FGF23 requires αKlotho as a coreceptor to mediate its renal effects (26, 27). In contrast, FGF23 induces hypertrophy of the left ventricle without αKlotho (28, 29). FGF23- or αKlotho-deficient mouse models exhibit rapid aging and age-related diseases that replicate human aging (24, 27). In humans, a high FGF23 plasma level can be caused by FGF23-producing tumors and result in osteomalacia (30). Inactivating mutations in the SIBLING (small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoprotein) dentin matrix protein (Dmp1) gene [autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR)] or the endopeptidase PHEX gene [X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH)] result in excessive FGF23 formation by osteoblasts/osteocytes and subsequent phosphaturia, hypophosphatemia, and low serum level of 1,25(OH)2D3 (25, 31–35).

The regulation of FGF23 production in the bone is only partly understood. 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances FGF23 expression via activation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) (36, 37). Parathyroid hormone (PTH) also stimulates FGF23 release (38–40). Dietary interventions affect FGF23, in that increased phosphorus uptake moderately enhances FGF23 secretion, whereas a low-phosphate diet decreases FGF23 serum concentration (41–43). Iron appears to be another regulator; however, its exact role has remained ill defined (44–48). It has been shown recently that the autonomous nervous system is also involved in the regulation of FGF23 formation, as sympathetic activation triggers FGF23 expression (49).

In this study, we explored whether GSK3 is involved in the regulation of FGF23 synthesis by investigating FGF23 formation in gsk-3KI and gsk-3WT (WT; wild-type) mice. Moreover, we studied the underlying mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All animal experiments were conducted according to the German law for the welfare of animals and were approved by the authorities of the state of Baden–Württemberg. We used gene-targeted mice carrying a mutant GSK3α,β, in which the codon encoding Ser9 of GSK3β gene was changed to encode nonphosphorylable alanine (GSK3β9A/9A), and the codon encoding Ser21 of GSK3α was changed simultaneously to encode the nonphosphorylable GSK3α21A/21A, thus yielding the GSK3α/β21A/21A/9A/9A double-knockin mouse (gsk3KI) (50). The mice were compared to age- and sex-matched WT mice (gsk3WT). The mice were studied at the age of 2–5 mo and had free access to water and standard chow (Ssniff, Soest, Germany). Where indicated, the mice were treated with the β-blocker propranolol (500 mg/L in drinking water; Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) for 1 wk.

Serum and plasma parameters

With the mice under light anesthesia, blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus into heparinized or EDTA-coated (in case of PTH analysis) capillaries on the day before the mice were placed in metabolic cages and on the last day of propranolol treatment. The following parameters were determined in serum or plasma. Intact FGF23 was measured with an ELISA kit from Kainos Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan), C-terminal FGF23 and PTH (1–84) by ELISAs from Immutopics (San Clemente, CA, USA), and 1,25(OH)2D3 by an ELISA from IDS (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Inorganic phosphate was measured by a photometric method (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and total calcium by flame photometry. Serum creatinine was assessed by enzymatic colorimetry (Labor & Technik, Berlin, Germany).

Urinary parameters

To obtain 24 h urine, the mice were placed in metabolic cages (Tecniplast, Hohenpeissenberg, Germany) individually and allowed to adapt to the new environment on the first 2 d. Then, 24 h urine was collected on the following 3 d in siliconized metabolic cages under water-saturated oil. The mice were again housed in metabolic cages from d 2–5 of propranolol treatment. The following urinary parameters were determined: phosphate by a photometric method (Roche), calcium by flame photometry, epinephrine by ELISA (Labor Diagnostika Nord, Nordhorn, Germany), and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) by ELISA (IBL, Frankfurt, Germany) in acidified urine. Urinary creatinine was assessed by the Jaffé method (Labor & Technik). All measurements were performed according to the manual provided by the manufacturer.

Renal Klotho abundance

Anesthetized mice were euthanized, and the kidneys were removed and immediately shock frozen in liquid nitrogen. The kidneys were then lysed in lysis buffer [54.6 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2.69 mM Na4P2O7, 360 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40] or RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Frankfurt, Germany), containing phosphatase and a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Complete mini; Roche), and the samples were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm and 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was removed and used for Western blot analysis. Tissue lysate (40 µg) was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blocked in 5% nonfat milk with Tris-buffered saline-Tween-20 (TBST) at room temperature for 1 h. After the membrane was probed overnight at 4°C with polyclonal rat anti-Klotho antibody (1:1000 in 5% fat-free milk in TBST; kindly provided by A. Saito, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Japan), it was washed several times and again incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rat secondary antibody (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed again, and the bands were visualized with ECL reagent (GE Healthcare-Amersham, Freiburg, Germany). For a loading control, the membrane was probed with GAPDH antibody (1:2000 in 5% bovine serum albumin in TBST; Cell Signaling Technology). Densitometric analysis was performed with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, München, Germany).

Blood pressure

Mean arterial blood pressure was determined with a noninvasive tail cuff system (IITC Life Science, Woodlands Hills, CA, USA). Several days of readings were averaged to obtain the systolic blood pressure for the respective mouse. All recordings and data analyses were obtained with a computerized data-acquisition system and software (PowerLab 4/26 and chart5; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA).

Cell culture

UMR106 rat osteosarcoma cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in standard culture conditions. The cells were treated with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 (Sigma-Aldrich) with or without 150 µM propranolol (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. Total RNA was isolated from the cells with Trifast reagent (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription of 2 µg RNA was performed with a random hexamer and SuperScriptIII Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific-Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) and the cDNA samples were treated with RnaseH (Thermo Scientific-Invitrogen).

qRT-PCR

For qRT-PCR analysis, the final volume of the RT-PCR reaction mixture was 20 µl and contained 2 µl cDNA, 1 µM of each primer, 10 µl GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), and sterile water up to 20 µl. PCR conditions were 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s. qRT-PCR was performed on a BioRad iCycler iQTM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad).

The following primers were used: rat Tbp (TATA box-binding protein), forward (5′–3′), ACTCCTGCCACACCAGCC, reverse (5′–3′), GGTCAAGTTTACAGCCAAGATTCA; and rat Fgf23, forward (5′–3′), TGGCCATGTAGACGGAACAC, reverse (5′–3′), GGCCCCTATTATCACTACGGAG. Calculated mRNA expression levels were normalized to the expression levels of Tbp of the same cDNA sample as internal reference. All PCRs were performed in duplicate. Relative quantification of gene expression was performed by the ΔΔCt method.

Statistics

Data are provided as means ± sem, with n indicating the number of independent experiments. All data were tested for significance with Student’s t test. Only results reaching P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

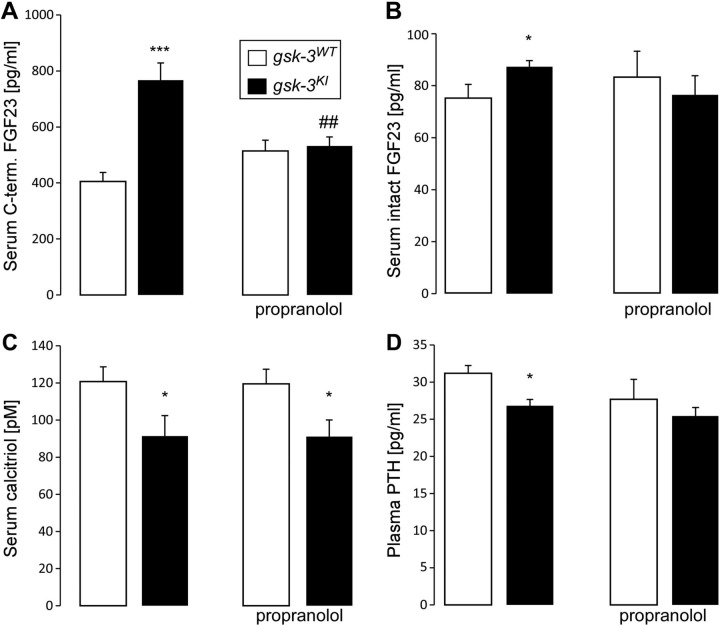

Gsk-3KI mice have been reported to have low serum phosphate (hypophosphatemia) and 1,25(OH)2D3 levels and loss of renal phosphate (phosphaturia) (10). The bone-derived hormone FGF23 induces all those effects. We therefore determined the serum C-terminal and intact FGF23 concentration. The serum concentration of C-terminal FGF23 was significantly (P < 0.05) higher in gsk-3KI mice (967 ± 229 pg/ml; n = 5) than in gsk-3WT mice (341 ± 37 pg/ml; n = 5). Also, the serum level of intact FGF23 was significantly (P < 0.01) higher in gsk-3KI mice (119 ± 21 pg/ml; n = 6) than in gsk-3WT mice (89 ± 8 pg/ml; n = 6).

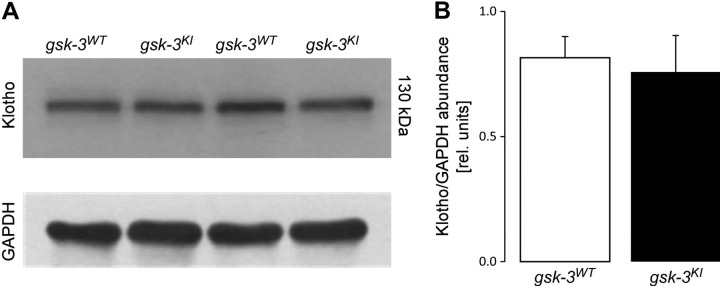

The renal effects of FGF23 are mediated by a receptor that requires αKlotho as a coreceptor (26, 27). As has been shown in Klotho-deficient mice, insufficient renal expression of αKlotho is associated with a high serum concentration of FGF23 (51). We therefore analyzed renal αKlotho expression by Western blot analysis. However, we did not find a difference in αKlotho expression between the genotypes (Fig. 1). Hence, altered αKlotho expression is not relevant to the elevated serum FGF23 level in gsk-3KI mice.

Figure 1.

Renal αKlotho expression is similar in gsk-3KI and gsk-3WT mice. A) Original Western blot demonstrating renal Klotho and GAPDH abundance. B) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot from (A). Data are arithmetic means ± sem (n = 6).

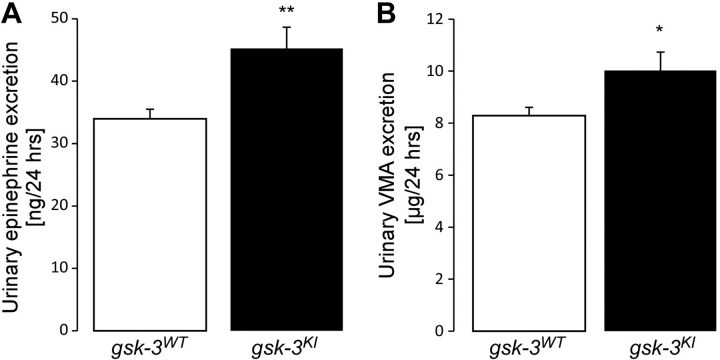

In an earlier study, the β-receptor agonist isoproterenol was shown to induce Fgf23 transcription in UMR106 osteoblast-like cells, suggesting that sympathetic activation is a known trigger of FGF23 release (49). Sympathetic activation can be estimated from the renal excretion of epinephrine, a major neurotransmitter of the sympathetic nervous system. The main metabolite of epinephrine is VMA. Urinary VMA is therefore another indicator of sympathetic activation. In line with another study (11), we found a significantly higher level of urinary epinephrine (Fig. 2A) and VMA excretion (Fig. 2B) in gsk-3KI mice than in gsk-3WT mice, pointing to enhanced activity of the sympathetic nervous system in gsk-3KI mice. As a consequence of the enhanced sympathetic activity, blood pressure was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in gsk-3KI mice (106 ± 2 mm Hg; n = 12) than in gsk-3WT mice (93 ± 2 mm Hg; n = 12). Treatment with propranolol abrogated the difference between the genotypes (gsk-3KI mice: 83 ± 2 mm Hg, n = 12; gsk-3WT mice: 84 ± 3 mm Hg, n = 12). As blood pressure may affect the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of the kidney, we determined creatinine clearance as a measure of GFR. Before propranolol treatment, GFR was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in gsk-3KI mice [8.4 ± 1.6 µl/min/g body weight (bw), n = 19] than in gsk-3WT mice (3.8 ± 0.5 µl/min/g bw; n = 19). Propranolol again abrogated the difference between the genotypes (gsk-3KI mice: 5.7 ± 0.7 µl/min/g bw, n = 19; gsk-3WT mice: 4.4 ± 0.7 µl/min/g bw, n = 19).

Figure 2.

Urinary excretion of epinephrine and VMA is enhanced in gsk-3KI mice vs. gsk-3WT mice. Data are arithmetic means ± sem (n = 7) of urinary 24 h epinephrine (A) and 24 h-VMA (B) excretion of gsk-3WT and gsk-3KI mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Next, we explored whether sympathetic activation accounts for enhanced FGF23 production and contributes to the phosphaturia in gsk-3KI mice. To this end, we treated gsk-3KI mice and gsk-3WT mice with propranolol for 1 wk. Before treatment, the serum FGF23 concentration was significantly higher in gsk-3KI mice than in gsk-3WT mice (Fig. 3A). Propranolol significantly reduced the elevated serum C-terminal FGF23 level, and, to a lesser extent, the intact FGF23 serum concentration (Fig. 3B) in gsk-3KI mice and abrogated the difference in serum FGF23 levels between the genotypes (Fig. 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Propranolol decreases the serum FGF23 level in gsk-3KI mice. (A–D) Serum C-terminal FGF23 (A; n = 20), intact FGF23 (B; n = 12), 1,25(OH)2D3 (C; n = 11–12), and PTH (D; n = 12) concentrations in gsk-3WT and gsk-3KI mice determined before and after 1 wk of treatment with propranolol. Data are arithmetic means ± sem. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, significant difference between the genotypes; ##P < 0.01, significant difference vs. no propranolol.

As a next step, we exposed UMR106 cells to propranolol to test whether β-blockade directly interferes with Fgf23 transcription in osteoblast-like cells. As a result, a 14 h incubation with 150 µM propranolol significantly (P < 0.05) down-regulated Fgf23 transcripts to 0.0021 ± 0.0001 arbitrary units (AU) (n = 15) compared to control cells (0.0027 ± 0.0002 AU; n = 15). Thus, propranolol inhibits FGF23 formation in vivo and in vitro.

As FGF23 suppresses the key enzyme for the generation of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the kidney, 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1α-hydroxylase, we also measured serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in gsk-3WT and gsk-3KI mice. The high serum FGF23 was paralleled by low 1,25(OH)2D3 in gsk-3KI mice, with or without propranolol (Fig. 3C). Another important regulator of 1,25(OH)2D3 is PTH. In line with low serum 1,25(OH)2D3, the serum PTH level was significantly reduced in gsk-3KI mice compared with the level in gsk-3WT mice (Fig. 3D).

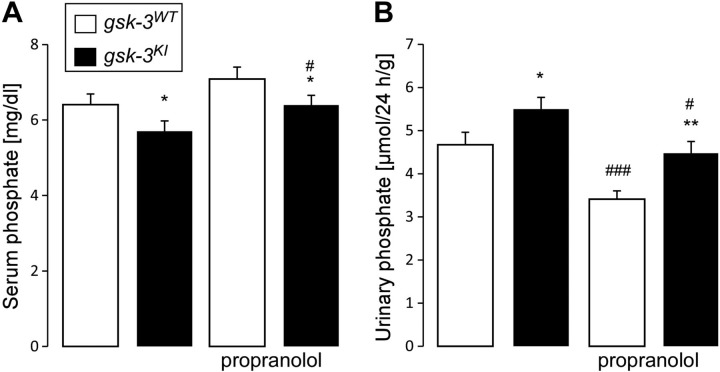

A high serum level of FGF23 is expected to induce phosphaturia, an effect already described in gsk-3KI mice (10). Therefore, we measured serum phosphate and renal phosphate excretion before and after treatment with propranolol. In line with the earlier report, we found a low serum phosphate concentration (hypophosphatemia) in gsk-3KI mice before treatment with propranolol (Fig. 4A). Despite hypophosphatemia, gsk-3KI mice had significantly higher renal phosphate excretion than did gsk-3WT mice (Fig. 4B). Treatment with propranolol significantly ameliorated the hypophosphatemia of gsk-3KI mice (Fig. 4A) and reduced their phosphaturia (Fig. 4B). We noted that β-blocker treatment also increased the serum phosphate level and decreased renal phosphate loss in gsk-3WT mice.

Figure 4.

Propranolol lowers the renal phosphate loss in gsk-3KI mice. Serum phosphate concentration (A; n = 19) and renal phosphate excretion (B; n = 19) in gsk-3WT and gsk-3KI mice determined before and after 1 wk of treatment with propranolol. Data are arithmetic means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, gsk-3KI mice vs. gsk-3WT mice; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, vs. no propranolol.

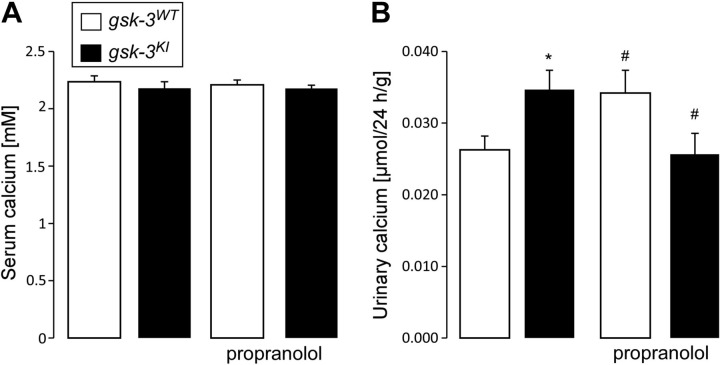

As reported earlier, gsk-3KI mice also have calciuria. We therefore studied whether propranolol influences the serum level and renal handling of calcium. Before treatment, gsk-3KI mice did not differ from gsk-3WT mice in serum calcium concentration (Fig. 5A), but had higher renal calcium excretion (Fig. 5B). Treatment with propranolol did not affect the serum calcium level but moderately blunted the calciuria in gsk-3KI mice.

Figure 5.

Propranolol lowers the renal calcium loss in gsk-3KI mice. Serum calcium concentration (A; n = 16–17) and renal calcium excretion (B; n = 19) in gsk-3WT and gsk-3KI mice determined before and after 1 wk of treatment with propranolol. Data are arithmetic means ± sem. *P < 0.05, gsk-3KI mice vs. gsk-3WT mice; #P < 0.05, vs. no propranolol.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that PKB/Akt/SGK-sensitive GSK3 influences the release of FGF23 by regulating the activity of the sympathetic nervous system.

We analyzed mice carrying a GSK3α/β mutation that renders the kinase insensitive to the inhibitory effect of PKB/Akt/SGK (gsk-3KI mice). Although normal insulin action requires inactivation of GSK3 through a PI3K/PKB/Akt/SGK-dependent mechanism, gsk-3KI mice are viable and do not have insulin resistance (50). However, gsk-3KI mice have been shown to have phosphaturia, calciuria, and demineralized bone. These effects were in part attributed to a direct inhibitory effect of GSK3 on the main phosphate transporter of the kidney, NaPiIIa (10). Our present study suggests that the renal phosphate loss of gsk-3KI mice is also caused by the high serum FGF23 level in these mice.

Commercially available ELISA kits allow measurement of either C-terminal plus full length (intact) FGF23 or intact FGF23 only. Inactive C-terminal FGF23 results from furin-dependent degradation of the biologically active intact FGF23 (52). In this study, we confirmed by using both types of FGF23 ELISA kit that the serum level of the active form of FGF23, intact FGF23, is indeed elevated in gsk-3KI mice.

The renal effects of FGF23 depend on sufficient expression of αKlotho in the cell membrane (51), and deficiency of this protein is associated with a dramatically elevated serum concentration of FGF23, suggesting that αKlotho is a regulator of serum FGF23. The expression of renal αKlotho, however, was not different between the genotypes.

The activity of the sympathetic nervous system is higher in gsk-3KI mice than in gsk-3WT mice. Hence, gsk-3KI mice have higher blood pressure and heart rate than do gsk-3WT mice (11). In the present study, we confirmed enhanced sympathetic activation of gsk-3KI mice by detecting significantly higher 24 h urinary excretion of epinephrine and of VMA, the main metabolite of epinephrine and norepinephrine. The hypertension of gsk-3KI mice was indeed caused by higher sympathetic activity, as propranolol abrogated the difference in blood pressure between the genotypes. As sympathetic activation has been shown to induce FGF23 release, we sought to define the role of the higher sympathetic activity for enhanced FGF23 formation in gsk-3KI mice. To this end, we treated gsk-3KI and gsk-3WT mice with the widely used β-blocker propranolol and analyzed the consequence for serum FGF23 and phosphate metabolism. As was obvious, enhanced sympathetic activation accounted for the excess FGF23 formation in gsk-3KI mice to a large extent: a 1 wk propranolol treatment greatly reduced the FGF23 level in gsk-3KI mice to the level in gsk-3WT mice. In vitro, β-blocker treatment similarly reduced Fgf23 formation in osteoblast-like cells.

As a result, hypophosphatemia and phosphaturia of gsk-3KI mice were also ameliorated by β-blocker treatment. This result emphasizes that the renal phosphate loss of gsk-3KI mice was at least in part the direct consequence of the high serum FGF23 concentration. Treatment with propranolol did not affect the low serum 1,25(OH)2D3 level in gsk-3KI mice, despite its profound effect on FGF23, 1 of the 2 main regulators of 1,25(OH)2D3 production. However, the other main regulator, PTH, which stimulates 1,25(OH)2D3 formation, was also low in gsk-3KI mice and was not significantly affected by propranolol, an effect that presumably contributes to the low serum 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration. In addition, it is possible that GSK3 signaling directly affects vitamin D metabolism or VDR signaling. In another study, treatment of mice with the GSK3 inhibitor lithium elevated the serum FGF23 level while lowering the serum calcitriol concentration (53). More research is needed to study the putative direct effects of GSK3 on vitamin D metabolism.

In line with findings in another study (54), GFR was significantly higher in gsk-3KI mice than in gsk-3WT mice. The profound blood pressure–lowering effect of β-blocker treatment in gsk-3KI mice was also associated with a lowering of GFR. Thus, the mild reduction of phosphaturia and calciuria in gsk-3KI mice after propranolol treatment could, at least in part, be caused by the decrease in GFR.

β-Blockers such as propranolol are widely prescribed for the treatment of hypertension, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation (55–57). It is tempting to speculate that the FGF23-lowering effect of β-blockers observed in gsk-3KI mice has an implication for millions of patients treated with β-blockers. These drugs clearly reduce the cardiovascular mortality of high-risk patients. In fact, a high FGF23 level correlates positively with cardiovascular mortality (28, 58, 59) and atrial fibrillation (60). Therefore, it appears possible that the benefit of β-blocker therapy is at least partially related to its ability to lower blood FGF23 concentration. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

We conclude that PKB/Akt/SGK-sensitive GSK3 signaling controls the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which is an important regulator of FGF23 production and phosphate metabolism. Hence, gsk-3KI mice expressing PKB/Akt-insensitive GSK3 exhibit a high serum FGF23 level, phosphaturia, and hypophosphatemia, effects that are all reversed by treatment with the β-blocker propranolol.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank E. Faber for technical assistance and L. Subasic for meticulous preparation of the manuscript. This study was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants Fo 695/1-1 (to M.F.), Fo 695/1-2 (to M.F.), and La 315/15-1 (to F.L.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol)

- AU

arbitrary units

- bw

body weight

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- KI

knockin

- NaPiIIa

sodium-dependent phosphate transporter IIa

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- SGK

serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase

- Tbp

TATA box-binding protein

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline–Tween-20

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- VMA

vanillylmandelic acid

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Allon M. (1992) Effects of insulin and glucose on renal phosphate reabsorption: interactions with dietary phosphate. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2, 1593–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFronzo R. A., Goldberg M., Agus Z. S. (1976) The effects of glucose and insulin on renal electrolyte transport. J. Clin. Invest. 58, 83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins P. T., Anderson K. E., Davidson K., Stephens L. R. (2006) Signalling through class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 647–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang F., Böhmer C., Palmada M., Seebohm G., Strutz-Seebohm N., Vallon V. (2006) (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1151–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw M., Cohen P., Alessi D. R. (1997) Further evidence that the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta by IGF-1 is mediated by PDK1/PKB-induced phosphorylation of Ser-9 and not by dephosphorylation of Tyr-216. FEBS Lett. 416, 307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakoda H., Gotoh Y., Katagiri H., Kurokawa M., Ono H., Onishi Y., Anai M., Ogihara T., Fujishiro M., Fukushima Y., Abe M., Shojima N., Kikuchi M., Oka Y., Hirai H., Asano T. (2003) Differing roles of Akt and serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase in glucose metabolism, DNA synthesis, and oncogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25802–25807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyatt A. W., Hussain A., Amann K., Klingel K., Kandolf R., Artunc F., Grahammer F., Huang D. Y., Vallon V., Kuhl D., Lang F.(2006) DOCA-induced phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 17, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhandaru M., Kempe D. S., Rotte A., Capuano P., Pathare G., Sopjani M., Alesutan I., Tyan L., Huang D. Y., Siraskar B., Judenhofer M. S., Stange G., Pichler B. J., Biber J., Quintanilla-Martinez L., Wagner C. A., Pearce D., Föller M., Lang F. (2011) Decreased bone density and increased phosphaturia in gene-targeted mice lacking functional serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 3. Kidney Int. 80, 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempe D. S., Ackermann T. F., Boini K. M., Klaus F., Umbach A. T., Dërmaku-Sopjani M., Judenhofer M. S., Pichler B. J., Capuano P., Stange G., Wagner C. A., Birnbaum M. J., Pearce D., Föller M., Lang F. (2010) Akt2/PKBbeta-sensitive regulation of renal phosphate transport. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 200, 75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Föller M., Kempe D. S., Boini K. M., Pathare G., Siraskar B., Capuano P., Alesutan I., Sopjani M., Stange G., Mohebbi N., Bhandaru M., Ackermann T. F., Judenhofer M. S., Pichler B. J., Biber J., Wagner C. A., Lang F. (2011) PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3 enhances phosphaturia and calciuria. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 873–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siraskar B., Völkl J., Ahmed M. S., Hierlmeier M., Gu S., Schmid E., Leibrock C., Föller M., Lang U. E., Lang F. (2011) Enhanced catecholamine release in mice expressing PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3. Pflugers Arch. 462, 811–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Y., Feng J. Q. (2011) FGF23 in skeletal modeling and remodeling. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 9, 103–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori M., Shimizu Y., Fukumoto S. (2011) Minireview: fibroblast growth factor 23 in phosphate homeostasis and bone metabolism. Endocrinology 152, 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsell R., Jonsson K. B. (2010) The phosphate regulating hormone fibroblast growth factor-23. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 200, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai X. Y., Miao D., Goltzman D., Karaplis A. C. (2003) The autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets R176Q mutation in fibroblast growth factor 23 resists proteolytic cleavage and enhances in vivo biological potency. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9843–9849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson T., Marsell R., Schipani E., Ohlsson C., Ljunggren O., Tenenhouse H. S., Jüppner H., Jonsson K. B. (2004) Transgenic mice expressing fibroblast growth factor 23 under the control of the alpha1(I) collagen promoter exhibit growth retardation, osteomalacia, and disturbed phosphate homeostasis. Endocrinology 145, 3087–3094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segawa H., Kawakami E., Kaneko I., Kuwahata M., Ito M., Kusano K., Saito H., Fukushima N., Miyamoto K. (2003) Effect of hydrolysis-resistant FGF23-R179Q on dietary phosphate regulation of the renal type-II Na/Pi transporter. Pflugers Arch. 446, 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada T., Mizutani S., Muto T., Yoneya T., Hino R., Takeda S., Takeuchi Y., Fujita T., Fukumoto S., Yamashita T. (2001) Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6500–6505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada T., Hasegawa H., Yamazaki Y., Muto T., Hino R., Takeuchi Y., Fujita T., Nakahara K., Fukumoto S., Yamashita T. (2004) FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimada T., Yamazaki Y., Takahashi M., Hasegawa H., Urakawa I., Oshima T., Ono K., Kakitani M., Tomizuka K., Fujita T., Fukumoto S., Yamashita T. (2005) Vitamin D receptor-independent FGF23 actions in regulating phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289, F1088–F1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrukhova O., Slavic S., Smorodchenko A., Zeitz U., Shalhoub V., Lanske B., Pohl E. E., Erben R. G. (2014) FGF23 regulates renal sodium handling and blood pressure. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 744–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spichtig D., Zhang H., Mohebbi N., Pavik I., Petzold K., Stange G., Saleh L., Edenhofer I., Segerer S., Biber J., Jaeger P., Serra A. L., Wagner C. A. (2014) Renal expression of FGF23 and peripheral resistance to elevated FGF23 in rodent models of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 85, 1340–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gattineni J., Twombley K., Goetz R., Mohammadi M., Baum M. (2011) Regulation of serum 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 levels by fibroblast growth factor 23 is mediated by FGF receptors 3 and 4. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F371–F377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada T., Kakitani M., Yamazaki Y., Hasegawa H., Takeuchi Y., Fujita T., Fukumoto S., Tomizuka K., Yamashita T. (2004) Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 561–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue Y., Segawa H., Kaneko I., Yamanaka S., Kusano K., Kawakami E., Furutani J., Ito M., Kuwahata M., Saito H., Fukushima N., Kato S., Kanayama H. O., Miyamoto K. (2005) Role of the vitamin D receptor in FGF23 action on phosphate metabolism. Biochem. J. 390, 325–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu M. C., Shiizaki K., Kuro-o M., Moe O. W. (2013) Fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho: physiology and pathophysiology of an endocrine network of mineral metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75, 503–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuro-o M. (2010) Overview of the FGF23-Klotho axis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 25, 583–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faul C., Amaral A. P., Oskouei B., Hu M. C., Sloan A., Isakova T., Gutiérrez O. M., Aguillon-Prada R., Lincoln J., Hare J. M., Mundel P., Morales A., Scialla J., Fischer M., Soliman E. Z., Chen J., Go A. S., Rosas S. E., Nessel L., Townsend R. R., Feldman H. I., St John Sutton M., Ojo A., Gadegbeku C., Di Marco G. S., Reuter S., Kentrup D., Tiemann K., Brand M., Hill J. A., Moe O. W., Kuro-O M., Kusek J. W., Keane M. G., Wolf M. (2011) FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4393–4408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seifert M. E., de Las Fuentes L., Ginsberg C., Rothstein M., Dietzen D. J., Cheng S. C., Ross W., Windus D., Dávila-Román V. G., Hruska K. A. (2014) Left ventricular mass progression despite stable blood pressure and kidney function in stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 39, 392–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jongh R. T., Vervloet M. G., Bravenboer N., Heijboer A. C., den Heijer M., Lips P. (2013) [Chronic bone pain due to raised FGF23 production? The importance of determining phosphate levels]. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 157, A5908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin A., Liu S., David V., Li H., Karydis A., Feng J. Q., Quarles L. D. (2011) Bone proteins PHEX and DMP1 regulate fibroblastic growth factor Fgf23 expression in osteocytes through a common pathway involving FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling. FASEB J. 25, 2551–2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quarles L. D. (2003) FGF23, PHEX, and MEPE regulation of phosphate homeostasis and skeletal mineralization. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 285, E1–E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenenhouse H. S., Sabbagh Y. (2002) Novel phosphate-regulating genes in the pathogenesis of renal phosphate wasting disorders. Pflugers Arch. 444, 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ADHR Consortium (2000) Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat. Genet. 26, 345–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White K. E., Jonsson K. B., Carn G., Hampson G., Spector T. D., Mannstadt M., Lorenz-Depiereux B., Miyauchi A., Yang I. M., Ljunggren O., Meitinger T., Strom T. M., Jüppner H., Econs M. J. (2001) The autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) gene is a secreted polypeptide overexpressed by tumors that cause phosphate wasting. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saini R. K., Kaneko I., Jurutka P. W., Forster R., Hsieh A., Hsieh J. C., Haussler M. R., Whitfield G. K. (2013) 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 expression in bone cells: evidence for primary and secondary mechanisms modulated by leptin and interleukin-6. Calcif. Tissue Int. 92, 339–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masuyama R., Stockmans I., Torrekens S., Van Looveren R., Maes C., Carmeliet P., Bouillon R., Carmeliet G. (2006) Vitamin D receptor in chondrocytes promotes osteoclastogenesis and regulates FGF23 production in osteoblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3150–3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavi-Moshayoff V., Wasserman G., Meir T., Silver J., Naveh-Many T. (2010) PTH increases FGF23 gene expression and mediates the high-FGF23 levels of experimental kidney failure: a bone parathyroid feedback loop. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 299, F882–F889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee Y., Bivi N., Farrow E., Lezcano V., Plotkin L. I., White K. E., Bellido T. (2011) Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in osteocytes increases the expression of fibroblast growth factor-23 in vitro and in vivo. Bone 49, 636–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee Y., Allen M. R., Condon K., Lezcano V., Ronda A. C., Galli C., Olivos N., Passeri G., O’Brien C. A., Bivi N., Plotkin L. I., Bellido T. (2011) PTH receptor signaling in osteocytes governs periosteal bone formation and intracortical remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 1035–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrari S. L., Bonjour J. P., Rizzoli R. (2005) Fibroblast growth factor-23 relationship to dietary phosphate and renal phosphate handling in healthy young men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 1519–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perwad F., Azam N., Zhang M. Y., Yamashita T., Tenenhouse H. S., Portale A. A. (2005) Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology 146, 5358–5364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fournier C., Rizzoli R., Ammann P. (2014) Low calcium-phosphate intakes modulate the low-protein diet-related effect on peak bone mass acquisition: a hormonal and bone strength determinants study in female growing rats. Endocrinology 155, 4305–4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takashi Y., Fukumoto S. (2015) Bone and nutrition: the relationship between iron and phosphate metabolism (in Japanese). Clin. Calcium 25, 1037–1042 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clinkenbeard E. L., Farrow E. G., Summers L. J., Cass T. A., Roberts J. L., Bayt C. A., Lahm T., Albrecht M., Allen M. R., Peacock M., White K. E. (2014) Neonatal iron deficiency causes abnormal phosphate metabolism by elevating FGF23 in normal and ADHR mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 361–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf M., Koch T. A., Bregman D. B. (2013) Effects of iron deficiency anemia and its treatment on fibroblast growth factor 23 and phosphate homeostasis in women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 1793–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imel E. A., Peacock M., Gray A. K., Padgett L. R., Hui S. L., Econs M. J. (2011) Iron modifies plasma FGF23 differently in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets and healthy humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 3541–3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farrow E. G., Yu X., Summers L. J., Davis S. I., Fleet J. C., Allen M. R., Robling A. G., Stayrook K. R., Jideonwo V., Magers M. J., Garringer H. J., Vidal R., Chan R. J., Goodwin C. B., Hui S. L., Peacock M., White K. E. (2011) Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1146–E1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawai M., Kinoshita S., Shimba S., Ozono K., Michigami T. (2014) Sympathetic activation induces skeletal Fgf23 expression in a circadian rhythm-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1457–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McManus E. J., Sakamoto K., Armit L. J., Ronaldson L., Shpiro N., Marquez R., Alessi D. R. (2005) Role that phosphorylation of GSK3 plays in insulin and Wnt signalling defined by knockin analysis. EMBO J. 24, 1571–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voelkl J., Alesutan I., Leibrock C. B., Quintanilla-Martinez L., Kuhn V., Feger M., Mia S., Ahmed M. S., Rosenblatt K. P., Kuro-O M., Lang F. (2013) Spironolactone ameliorates PIT1-dependent vascular osteoinduction in klotho-hypomorphic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 812–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhattacharyya N., Wiench M., Dumitrescu C., Connolly B. M., Bugge T. H., Patel H. V., Gafni R. I., Cherman N., Cho M., Hager G. L., Collins M. T. (2012) Mechanism of FGF23 processing in fibrous dysplasia. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1132–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fakhri H., Pathare G., Fajol A., Zhang B., Bock T., Kandolf R., Schleicher E., Biber J., Föller M., Lang U. E., Lang F. (2014) Regulation of mineral metabolism by lithium. Pflugers Arch. 466, 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boini K. M., Amann K., Kempe D., Alessi D. R., Lang F. (2009) Proteinuria in mice expressing PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F153–F159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mancia G., Fagard R., Narkiewicz K., Redón J., Zanchetti A., Böhm M., Christiaens T., Cifkova R., De Backer G., Dominiczak A., Galderisi M., Grobbee D. E., Jaarsma T., Kirchhof P., Kjeldsen S. E., Laurent S., Manolis A. J., Nilsson P. M., Ruilope L. M., Schmieder R. E., Sirnes P. A., Sleight P., Viigimaa M., Waeber B., Zannad F.; Task Force Members (2013) 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J. Hypertens. 31, 1281–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto K. (2015) β-Blocker therapy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: importance of dose and duration. J. Cardiol. 66, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camm A. J., Lip G. Y., De Caterina R., Savelieva I., Atar D., Hohnloser S. H., Hindricks G., Kirchhof P.; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) (2012) 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur. Heart J. 33, 2719–2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parker B. D., Schurgers L. J., Brandenburg V. M., Christenson R. H., Vermeer C., Ketteler M., Shlipak M. G., Whooley M. A., Ix J. H. (2010) The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 640–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gutiérrez O. M., Januzzi J. L., Isakova T., Laliberte K., Smith K., Collerone G., Sarwar A., Hoffmann U., Coglianese E., Christenson R., Wang T. J., deFilippi C., Wolf M. (2009) Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 119, 2545–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathew J. S., Sachs M. C., Katz R., Patton K. K., Heckbert S. R., Hoofnagle A. N., Alonso A., Chonchol M., Deo R., Ix J. H., Siscovick D. S., Kestenbaum B., de Boer I. H. (2014) Fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident atrial fibrillation: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). Circulation 130, 298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]