INTRODUCTION

Cancer survivors spend more out of pocket (OOP) for medical care than their counterparts without a cancer history, a pattern that persists many years after cancer diagnosis and completion of treatment.1 This excess financial burden for patients with cancer, survivors, and their families has continued to grow as the costs of cancer care have increased dramatically in the past decades,2,3 with many new cancer drugs priced at $100,000 or higher annually.4 Furthermore, health insurers are increasingly shifting costs of care to patients through higher deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance.5 Compounding matters is the negative impact of cancer on employment,1,6 resulting in forgone income and loss of employment-sponsored health insurance for some patients. Consequently, patients with cancer and their families experience financial hardship associated with cancer, including problems paying medical bills, distress and worry about medical bills, and delaying or forgoing of medical care because of costs.7

In 2009, the Cost of Care Task Force at ASCO identified patient-physician cost communication as a critical component of high-quality care8; in 2013, the Institute of Medicine echoed this sentiment,9 and in 2018, the President’s Cancer Panel recognized the need to address high cancer drug prices as a national priority.10 In this article, we provide an overview of medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States and associated outcomes. We then present a conceptual framework to elucidate the conditions that lead to or worsen hardship and use the framework to guide discussion of potential interventions and strategies at the patient, provider, practice, employer, insurer, and state and national policy levels to prevent and mitigate financial hardship.

OVERVIEW OF FINANCIAL HARDSHIP AMONG CANCER SURVIVORS

Definition, Measurement, and Prevalence of Financial Hardship

Several terms are used in the literature to describe financial hardship, including financial toxicity, financial distress, financial burden, and financial problems.7 Measures of medical financial hardship encompass 3 domains: material conditions, psychological response, and coping behaviors.7 Material conditions comprise OOP expenses for medical costs as a percentage of household income; productivity losses resulting from limited ability to work; reduction in income, assets, and net worth; and medical debt, trouble paying medical and other household bills, and bankruptcy.7 Psychological response is the stress, distress, and worry about affording care or paying medical bills or concerns about work impairment associated with cancer. Coping behaviors that survivors adopt when facing growing OOP expenses and distress include delaying or forgoing medical care because of cost and nonadherence to medications for cancer and other conditions.

Although study populations and measures of financial hardship vary, more than half of cancer survivors in the United States report at least one domain of hardship, and nearly one third report multiple hardship domains.11 Much of the research to date has evaluated the material financial hardship domain,7 in part because information on OOP expenses has been collected in publicly available secondary data sources, such as the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). A growing body of research is addressing psychological hardship, although heterogeneity in measurement limits comparisons across studies. Within the behavioral domain of financial hardship, research has primarily focused on delaying or forgoing prescription drugs because of cost or inability to pay. Especially in the case of oral anticancer drugs, patients may experience so-called sticker shock at the pharmacy and abandon treatment altogether before initiation.12-14

Health Outcomes of Financial Hardship

Research suggests that financial hardship leads to worse health outcomes, even after adjusting for traditional measures of socioeconomic status (SES). Several cross-sectional and cohort studies have reported that financial hardship is associated with worse health-related quality of life (QOL)15 and less satisfaction with care.16 In a cohort study of colorectal and lung cancer survivors, those with less than 12 months of financial reserves to maintain their current living standard (68% and 64%, respectively) reported lower QOL and increased symptom burden than survivors with at least 12 months of financial reserves.17 In a longitudinal study, cancer survivors in Washington state who filed for bankruptcy were at significantly increased risk of mortality compared with similar cancer survivors who did not file for bankruptcy.18 This study did not evaluate the effects of less extreme forms of the material domain of financial hardship other than bankruptcy or measures within psychological or behavioral financial hardship domains. Other longitudinal studies conducted in the general adult population in the United States have demonstrated adverse consequences of financial hardship for all-cause mortality.19 Disentangling these complex associations is an important area for future research.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH FINANCIAL HARDSHIP AND POTENTIAL INTERVENTIONS

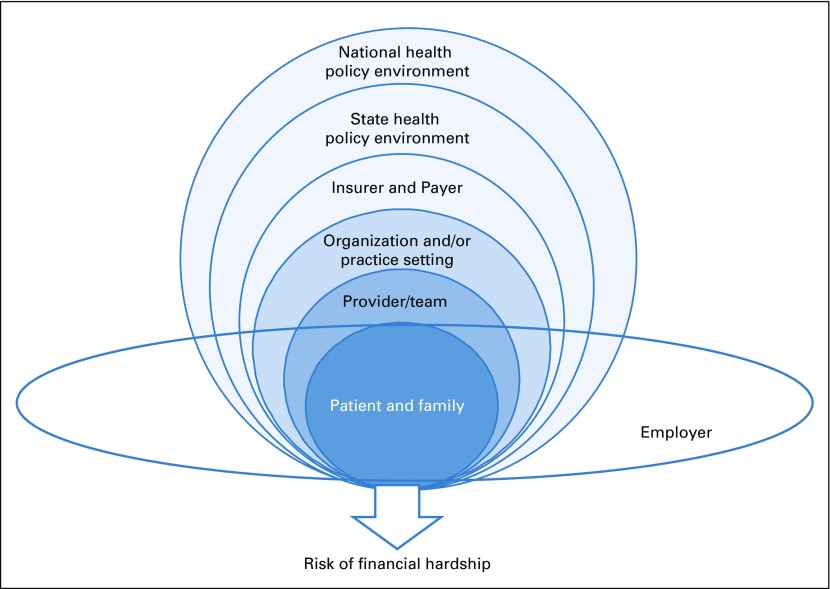

The conceptual framework depicted in Figure 1 illustrates that factors influencing the risk of financial hardship are multilevel.20 At the center of the framework are patients with cancer, survivors, and their families, surrounded by concentric circles representing the influences of providers and provider care teams, health care systems, and state and national policies. The framework includes an employer level because health insurance and other benefits are mainly employer based for the working-age population and their spouses and dependents. National policies, such as the Americans With Disabilities Act and the Family Medical Leave Act, differentially apply to large and small employers, and states often have additional policies that may apply. Benefits, such as paid and unpaid sick leave, vacation policies, and retiree benefits, also vary by employer.20

FIG 1.

Factors at multiple levels associated with medical financial hardship. Conceptual framework with multiple hierarchic levels starting with cancer survivors and their families in the center, surrounded by provider and provider care teams, insurer and payer, and state and national policy levels. An employer level is also in the framework and intersects with all other levels. Figure adapted.20

Patient Level

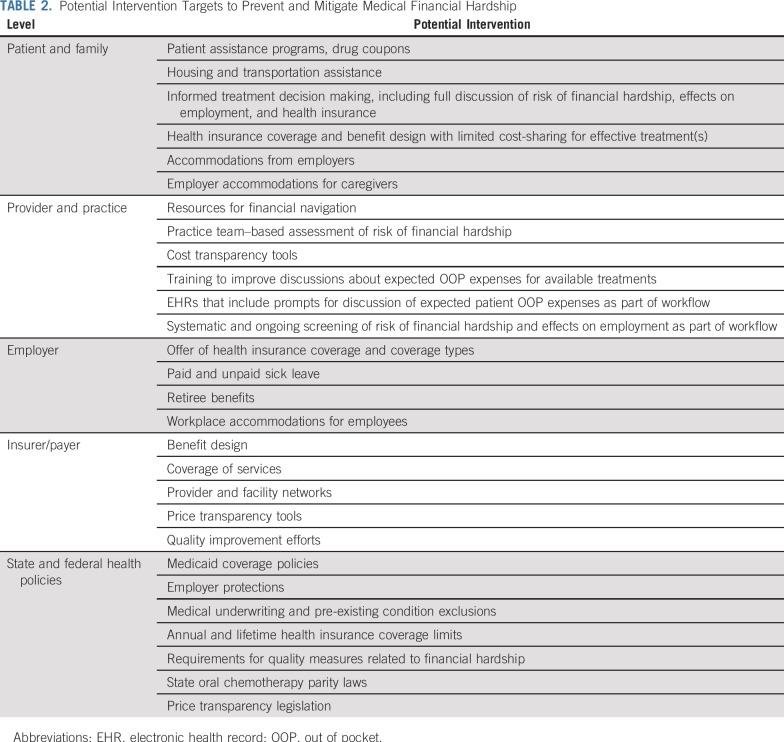

Socioeconomic and clinical characteristics of patients with cancer and survivors are associated with multiple domains of medical financial hardship in cross-sectional studies (Table 1).20 Lower household income and/or educational attainment,15,21,22 minority race/ethnicity,21-24 rural residence,25 and being unmarried are positively associated with financial hardship.21,23,26 Clinical characteristics, including cancer site,18,23 stage,18,22 and type of treatment and/or treatment intensity22,23 or duration, are associated with hardship, as is comorbidity.11 National data show that working-age cancer survivors are more likely to report all domains of financial hardship than their counterparts without a cancer history, even after adjusting for SES and comorbidity. Reductions in employment or hours worked as a result of cancer are associated with hardship,27 and because most health insurance for the working-age population is employer based, changes in employment can reduce income and affect access to health insurance coverage as well.

TABLE 1.

Patient Factors Associated With Medical Financial Hardship

The absence of health insurance coverage is one of the strongest correlates of medical financial hardship.28 Among those age 18 to 64 years, uninsured cancer survivors report substantially greater levels of financial hardship than their counterparts with private or public health insurance coverage.21,22,26 Material and behavioral financial hardship are nearly twice as common in the uninsured than in those with private health insurance coverage.27 Mounting evidence further elucidates the relationship between benefit design in private health insurance and the prevalence of medical financial hardship. Cancer survivors with high-deductible private insurance without health savings accounts are more likely to report material, psychological, or behavioral hardship than survivors without high-deductible plans.29 Patient cost sharing can also vary by care setting (eg, inpatient v outpatient) and by whether cancer treatment is administered orally (covered by pharmacy benefit or Medicare Part D) or intravenously (covered by medical benefit or Medicare Part B). Among insured patients who initiate cancer treatment, higher cost sharing is associated with treatment nonadherence and discontinuation.30 Higher cost sharing is also associated with nonadherence to treatments for other chronic conditions among patients with cancer. Financial hardship seems to be greatest in younger (ie, age ≤ 45 years) working-age cancer survivors,31,32 suggesting disruptions in education and employment as a result of cancer and its treatment early in career and professional development may more negatively affect asset accumulation for younger cancer survivors. Risk of bankruptcy and higher levels of debt are also reported in this younger adult group who may lack alternatives to employer-based coverage and are often responsible for dependent children.31,32

Financial hardship is less common among cancer survivors age 65 years or older, who are age eligible for Medicare coverage, than survivors age 18 to 64 years.21,26,31 Age-related differences likely reflect the protective effects of Medicare coverage, despite higher prevalence of comorbidity33 and greater health care use in the older age group.33 Although those age 65 years or older have nearly universal Medicare insurance, financial hardship varies by type of supplemental coverage. Among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with cancer, those without supplemental coverage are much more likely to report higher OOP expenses than beneficiaries with private supplemental insurance.34,12-14

Informal caregivers of patients with cancer, including spouses, children, parents, and friends, also experience financial hardship, but little research has focused on them. Productivity losses are common among caregivers, especially those who accompany patients to medical care appointments and treatments.35,36 Employment disruptions and resulting income loss during informal caregiving37 may further lead to caregiver psychological distress and a decision to delay or forgo their own care. Extended employment disruptions and caregiver financial hardship are especially relevant for families of pediatric and young adult patients with cancer.38 In a small single-institution study, one quarter of parents of pediatric patients with cancer reported a loss of 40% of household income within 6 months of their child’s cancer diagnosis and treatment with chemotherapy.39

At the patient level, efforts to address financial hardship include connections to patient assistance programs and improvement in access to prescription drugs, drug coupons, and savings card programs.40 Other programs provide assistance with transportation and housing for patients traveling for specialized cancer treatment.41 Patients with cancer and their families are not systematically screened for risk of financial hardship, and data about the use of patient assistance programs are scarce. Therefore, little is known about the effectiveness of patient assistance programs in reducing financial hardship or improving health outcomes.

Provider and Practice Levels

At the provider and practice levels, several pilot studies have explored the feasibility of introducing financial navigators to address financial barriers to care,42,43 although the effectiveness of these programs has not been formally evaluated. Providers are especially important in addressing financial hardship, because they play a central role in discussing expected benefits and harms of treatment, ideally including the cost of care and risk of financial hardship, to help patients make informed treatment decisions. Because of the cumulative effects of OOP expenses and income loss during cancer treatment and survivorship care, risk of financial hardship varies in severity over the course of care. Therefore, ongoing communication about financial hardship, rather than a single discussion at diagnosis or treatment initiation, is critical. Although oncologists generally agree about their responsibility for these discussions,44 such discussions are rare,44 and many oncologists feel uncomfortable engaging in them.44 Insufficient physician time, lack of cost transparency, and provider financial knowledge may be additional barriers to cost communication. Patients’ and their families’ response to these discussions is unknown. When asked about their attitudes regarding cost communication, more than 50% of patients desired discussions about OOP expenses, but only approximately 33% actually had them.44 It is unknown whether such communication included potential effects of treatment on employment and health insurance eligibility.

Price transparency tools45 and provider training materials and practice guides are increasingly available.46 Some training materials also address spending for transportation to and from medical care, childcare and eldercare, housing, and food.46 Because patients may not work during treatment, minimizing lost wages and maintaining access to employer-sponsored health insurance are additional topics that are increasingly recommended for informed decision making.46,47 Little research has addressed the uptake of tools and training materials or their effectiveness in improving provider-patient communication, mitigating financial hardship, and improving patient outcomes.

Employer Level

Employer-level factors, including availability of health insurance and types of coverage options, paid and unpaid sick leave, and workplace accommodations, likely play a large role in medical financial hardship for employed cancer survivors. These formal and informal benefits will also affect employed informal caregivers in their ability to support cancer survivors while securing insurance and income for the family. Generosity of retirement benefits, including supplemental health insurance and pensions from former employers, can affect the risk of financial hardship among retired cancer survivors. Trends toward less generous retiree benefits may exacerbate financial hardship in the future. Although there is considerable research on how cancer diagnosis and treatment limit employment, less is known about how employers and their benefit offerings alter the risk of financial hardship among patients and their families.

Insurer and Payer Levels

Increasingly, private insurers and state Medicaid programs have implemented value-based payment models focusing on improving patient outcomes and quality of care, including medical homes in oncology and oncology pathways.48,49 Other system-level factors, such as breadth and depth of provider networks, benefit design, use of electronic health records (EHRs) in quality improvement, participation in alternative payment programs, and infrastructure for financial assistance, are likely associated with patient financial hardship, but little research has been conducted in these areas. Payers have detailed information on the cost of care and patients’ OOP expenses. These data, coupled with surveys of beneficiaries, may provide a better understanding of financial hardship and its consequences across benefit design and cancer care delivery approaches.

State and National Policy Levels

State and national policies are especially relevant for research evaluating medical financial hardship because many health insurance and employment regulations are enacted at these levels. The Medicaid and Medicare programs provide care for millions of cancer survivors. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010 enacted several provisions that affect health insurance coverage nationally, including introduction of the marketplace coverage and essential health benefit standards, elimination of pre-existing condition exclusions and lifetime and annual coverage limits, dependent coverage for young adults to remain covered under their parents’ private health insurance until age 26 years, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility. Many ACA provisions are associated with improved coverage, access to preventive services, and earlier stage at diagnosis.50 Little research has addressed the effects of these provisions on financial hardship in patients with cancer and survivors. Several trends and policies that increase the risk of underinsurance and uninsurance have emerged, including private short-term insurance plans, which are not required to cover pre-existing conditions and frequently do not cover prescription drugs,51 as well as Medicaid work requirements in some states.52

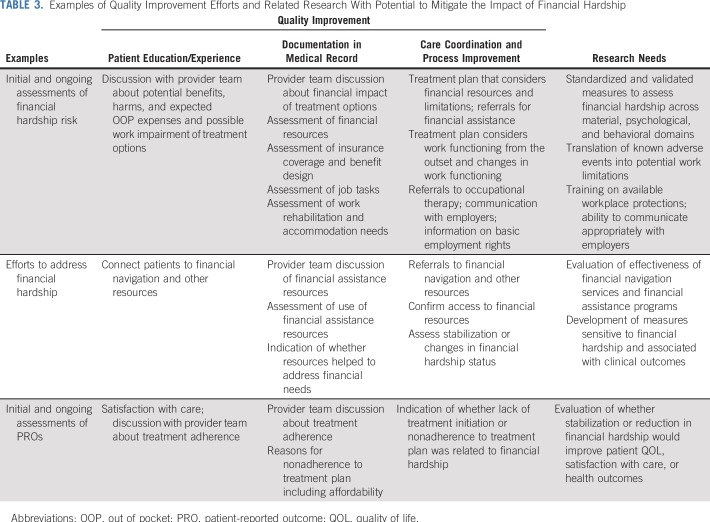

This section explains how factors at each level of our conceptual framework affect medical financial hardship. In-depth understanding of these factors is helpful in identifying intervention targets at each level for preventing and mitigating medical financial hardship, as discussed here and summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Potential Intervention Targets to Prevent and Mitigate Medical Financial Hardship

PROPOSED STRATEGIES TO PREVENT AND MITIGATE FINANCIAL HARDSHIP

Despite the growing interest in cancer-related financial hardship and the recognition of detrimental consequences for the physical and economic well-being of patients and families, the data to study financial hardship at a population level and across patients and treatments are limited. Data are needed to better characterize risk factors for financial hardship, trajectories over the course of cancer treatment and survivorship care, and patient outcomes. These data are necessary for developing and assessing the effectiveness of interventions at multiple levels to prevent and mitigate financial hardship across the cancer continuum. Few validated measures of financial hardship that address material, psychological, and behavioral domains exist. Among the few validated measures are the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale53 and the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity measure.54 Although nationally representative household surveys such as the National Health Interview Survey and the MEPS contain items on medical financial hardship within material, psychological, and behavioral domains that can be used in comparisons of individuals with and without a cancer history, sample sizes are generally insufficient to draw conclusions regarding particular insurance plans and specific cancer sites or treatment. Standardized measures and/or items from the publicly available surveys can be used in studies with primary data collection for cross-sectional, cohort, and other studies to allow meaningful comparisons with nationally representative populations.

Interventions to prevent or reduce financial hardship should yield better physical, emotional, and financial well-being among cancer survivors and their families. Although not specific to patients with cancer, one patient-level strategy is to promote financial planning to improve economic well-being and financial solvency; currently, 40% of Americans cannot cover an unexpected expense over $400.55 However, strategies to boost patients’ financial well-being may not be sufficient, because the high cost of cancer treatments and adverse effects on employment can still push some wealthier patients into financial hardship.

One possible provider-level strategy is improving the frequency and content of patient-provider communication about expected OOP expenses. Normalizing these conversations in all patients will minimize stigmatization and underidentification of those who are at risk for hardship, despite apparent material resources. A hindrance to cost communication is the lack of readily available information about expected OOP expenses. Although many states have mandated that health care providers make price information available to consumers56 in an effort to promote price transparency, some argue that state legislation has limited relevance to cancer because they target commonly used, clearly defined procedures and services.57 Efforts specifically targeted at improving price transparency in cancer care have produced Web-based tools such as eviti ADVISOR58 or DrugAbacus.59 However, the former can only be accessed by registered health care providers with a tax ID and National Provider Identifier number, and neither tool generates estimates on OOP expenses.57 Acknowledging the importance of cost communication, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) identified measuring, understanding, and addressing financial hardship as one of its top priorities.60 The lack of information on OOP expenses for cancer treatment has also prompted the NCI to solicit development of digital platforms to streamline the calculation of OOP expenses for patients with cancer.

Whether cost communication alone can be effective in preventing and mitigating financial hardship is uncertain. The literature to date provides little evidence on the association between cost communication and outcomes. A review article on cost communication discussed 3 outcome measures (patient satisfaction, medication adherence, and OOP expenses)44 and reported that cost communication was associated higher patient satisfaction61 and lower OOP expenses62 but higher odds of medication nonadherence. Nevertheless, cost communication offers an opportunity to identify patients who are at highest risk of financial hardship and to intervene by modifying treatment regimens and/or connecting patients to financial assistance programs. From this perspective, policy efforts to battle tobacco use offer a possible path forward to tackle financial hardship through raising provider awareness to prompt action when necessary. Under the ACA, health care providers are required to adopt meaningful use of a certified EHR. By including the recording of smoking status for patients age 13 years or older as a core measure and requiring documentation of smoking status for more than 80% of these patients to meet the stage 3 meaningful use objective,63 research has found that the rate of coding smoking behavior in claims data more than doubled between 2009 and 2014.64 Similar to the inquiry into patients’ smoking status, a policy requiring systematic documentation of patients’ financial hardship status at initial clinical encounters could trigger additional actions to identify and help patients at greatest risk of financial hardship. A 3-step approach modeled from the Ask Advise Refer approach, recommended by the US Department of Health and Human Services for tobacco control, offers a promising cancer care delivery model to systematically address financial hardship.57 This approach would emphasize the importance of asking about financial hardship, advising patients who are at risk of hardship, and then referring patients to financial assistance and other resources.

The evolving nature of patients’ financial standing through the journey of their treatment makes it challenging to capture information throughout the disease trajectory. A baseline assessment of financial hardship is necessary but insufficient. We recommend collecting measures of financial hardship and economic outcomes frequently, preferably at the same intervals when other patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures are collected. This will not only allow researchers to correlate financial outcomes with PRO measures, but also offer more complete data capture of financial consequences longitudinally, reflecting how patients’ experiences change over their treatment and survivorship trajectory.

Payers are a potential source of data for better understanding financial hardship. Insurers have information on billed charges, paid amounts, and patient cost-sharing responsibility. Although lacking patient-specific data on hardship, insurer-level data nonetheless allow researchers to address important questions about accumulating costs and treatment nonadherence. Although such studies are correlational and not causal, relationships about the amount expended from payers and patients for treatments received at a nonefficacious dose can be discovered and mitigated. Moreover, combined with EHRs, insight into other types of toxicities and symptoms can be gained in relation to rising OOP expenses. As more PRO data are collected in EHRs, it is possible to add measures of financial hardship, leading to a more comprehensive view of its prevalence, trajectory, and effects on health outcomes. Such studies can be conducted within large health systems, providing a model for future, larger-scale studies.

Employers, like payers, have an important role in recognizing and limiting the consequences of financial hardship. In the absence of national and state policies to protect ill workers from loss of income and/or benefits, employers are key to developing and implementing strategies that reduce the consequences of cancer in the workplace,47 which ultimately cushion many patients from the full brunt of financial hardship.

Employers can reduce financial hardship by providing a steady source of income and access to health insurance and other benefits. Job retention can be enhanced through formal means (sick leave policies, work accommodations, flexibility) and informal means (effective communication about expectations, supportive work environment). Paid sick leave and affordable health insurance are critical needs shared by all workers, regardless of their health status. However, when employees become ill, they are faced with tradeoffs between caring for themselves and maintaining their jobs and health insurance. More than 90% of employed breast cancer survivors who had health insurance through their job stated that they were working to maintain health insurance, highlighting the critical role employers play in the lives of cancer survivors.65 Extended absences put employees at risk for losing their jobs. Moreover, a reduction in hours worked can put employees at risk for losing benefits, such as health insurance and paid sick leave, even if they maintain their jobs. Many employers have a threshold of hours worked for employees to qualify for health insurance and leave accumulation. Once an employee drops below these thresholds, benefits may cease. Formal policies and procedures to address these issues include relaxing thresholds for hours worked, providing clear communication about benefits and requirements, and having alternatives for employees who cannot work (eg, short-term disability).

Informal methods that facilitate job retention and allow flexible work schedules are also effective. Evidence suggests that many employers want to create a supportive work environment for survivors, but there is limited understanding of what needs to be done and of the feasibility, cost, effectiveness, and sustainability of accommodation policies and strategies.47 A compassionate worksite with empathetic supervisors and coworkers can make job retention easier.66 In contrast, survivors who experienced cancer-related discrimination were less likely to return to work after cancer treatment.67 Willingness to provide simple accommodations, such as laptop computers to facilitate working from home68 or a return-to-work plan that makes expectations explicit, can improve work retention.69 All of these measures are important in an era of long-term or lifetime cancer treatments.

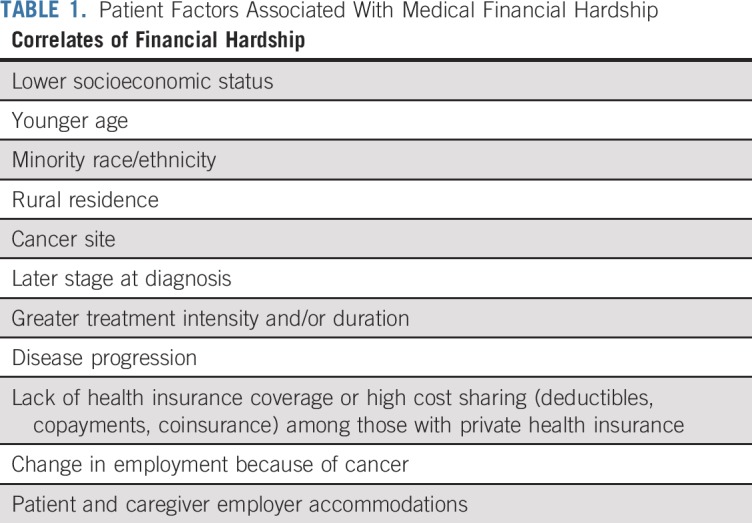

As the patient, provider, payer, employer, and policy communities consider financial hardship and its impact on many levels, one way to frame, and perhaps mitigate, financial hardship associated with cancer is within the quality improvement (QI) context. QI is frequently conceptualized as symptom management, guideline concordance, treatment timeliness, and physical and mental health preservation.70 Measures that screen, detect, and reduce financial hardship could also be encompassed under the QI umbrella. As summarized in Table 3, standardized and systematic screening of patients with cancer and survivors for financial hardship, including health insurance coverage benefits, employment characteristics, and sick leave and other benefits, documentation of provider discussions of the expected OOP expenses and actions to address financial hardship, and use of endorsed and validated measures of financial hardship would incentivize the actions recommended by professional societies and other organizations.9

TABLE 3.

Examples of Quality Improvement Efforts and Related Research With Potential to Mitigate the Impact of Financial Hardship

In summary, in this article, we provided an overview of research on medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. We identified numerous research gaps and discussed strategies to prevent and mitigate financial hardship at the patient, provider, practice, payer, health system, employer, and state and national policy levels. With trends toward rising costs of treatment,2,3 greater treatment intensity, and higher patient cost sharing, especially for oral medications,2,71 the cumulative risk of financial hardship will likely increase in the future. The increasing prevalence of cancer survivorship in the United States underscores the need to address measurement and data infrastructure gaps that may hinder development of effective interventions necessary for these efforts.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA207216, R01CA225647, and CCSG P30 CA016672).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Understanding Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors in the United States: Strategies for Prevention and Mitigation

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jco/site/ifc.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Ya-Chen Tina Shih

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guy GP, Jr, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3749–3757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shih YT, Xu Y, Liu L, et al. Rising prices of targeted oral anticancer medications and associated financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2482–2489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JA, Roehrig CS, Butto ED. Cancer care cost trends in the United States: 1998 to 2012. Cancer. 2016;122:1078–1084. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Specialty drug pricing and out-of-pocket spending on orally administered anticancer drugs in Medicare Part D, 2010 to 2019. JAMA. 2019;321:2025–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation Payments for cost sharing increasing rapidly over time. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/payments-for-cost-sharing-increasing-rapidly-over-time/

- 6.Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(suppl 11):2151–2159. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109:djw205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine . Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. President’s Cancer Panel: Promoting value, affordability, and innovation in cancer drug treatment: A report to the President of the United States from the President’s Cancer Panel. https://prescancerpanel.cancer.gov/report/drugvalue/

- 11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31913. Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al: Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer 125:1737-1747, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, et al. Association of patient out-of-pocket costs with prescription abandonment and delay in fills of novel oral anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:476–482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, et al. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(suppl):46s–51s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB. Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4323–4328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, et al. Determinants and consequences of financial hardship among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst . 2019;111:189–200. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:414–420. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker-Seeley RD, Li Y, Subramanian SV, et al. Financial hardship and mortality among older adults using the 1996-2004 Health and Retirement Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: What do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:1389–1397. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rim SH, Guy GP, Jr, Yabroff KR, et al. The impact of chronic conditions on the economic burden of cancer survivorship: A systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16:579–589. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2016.1239533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, et al. Financial impact of breast cancer in black versus white women. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1695–1701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: Experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1269–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer NR, Geiger AM, Lu L, et al. Impact of rural residence on forgoing healthcare after cancer because of cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1668–1676. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banegas MP, Guy GP, Jr, de Moor JS, et al. For working-age cancer survivors, medical debt and bankruptcy create financial hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:54–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Han X, et al. Prevalence and correlates of medical financial hardship in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1494–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05002-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125:1737–1747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Doroudi M, Coughlan D, Banegas MP, et al: Is cancer history associated with assets, debt, and net worth in the United States? JNCI Cancer Spectr 2:pky004, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Guy GP, Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Economic burden of chronic conditions among survivors of cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2053–2061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:757–765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, et al. Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15:883–893. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(suppl):4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal O. The impact of cancer on spouses’ labor earnings: A population-based study. Cancer. 2009;115(suppl):4350–4361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Z, Yabroff KR. The long shadow of childhood cancer: Lasting risk of medical financial hardship. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:105–106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bona K, London WB, Guo D, et al. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:105–111. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zullig LL, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, et al. The role of patient financial assistance programs in reducing costs for cancer patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:407–411. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Cancer Society Programs and resources to help with cancer-related expenses. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/finding-and-paying-for-treatment/understanding-health-insurance/if-you-have-trouble-paying-a-bill/programs-and-resources-to-help-with-cancer-related-expenses.html

- 42.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122–e129. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3958-3. Spencer JC, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, et al: Oncology navigators’ perceptions of cancer-related financial burden and financial assistance resources. Support Care Cancer 26:1315-1321, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shih YT, Chien CR. A review of cost communication in oncology: Patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcome assessment. Cancer. 2017;123:928–939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mayo Clinic: Cost estimator. https://costestimator.mayoclinic.org/

- 46. America’s Essential Hospitals: Cost of care conversations resources. https://essentialhospitals.org/cost-of-care/provider-tools/

- 47.Bradley CJ, Brown KL, Haan M, et al. Cancer survivorship and employment: Intersection of oral agents, changing workforce dynamics, and employers’ perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newcomer LN, Malin JL. Payer view of high-quality clinical pathways for cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:148–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.020503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:114–116. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, et al. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3906–3915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pollitz K, Long M, Semanskee A, et al: Understanding short-term limited duration health insurance. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/understanding-short-term-limited-duration-health-insurance/

- 52. Kaiser Family Foundation: What are states proposing for work requirements in Medicaid? https://www.kff.org/medicaid/press-release/what-are-states-proposing-for-work-requirements-in-medicaid/

- 53.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, et al. The Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Establishing validity and reliability. Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer. 2017;123:476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2017. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2017-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201805.pdf.

- 56.de Brantes F, Delbanco S. Report Card on State Price Transparency Laws—July 2016. Newtown, CT: Connecticut Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shih YT, Nasso SF, Zafar SY. Price transparency for whom? In search of out-of-pocket cost estimates to facilitate cost communication in cancer care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:259–261. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. NantHealth|Eviti: eviti Advisor. https://connect.eviti.com/evitiAdvisor/

- 59. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Drug Pricing Lab: Drug Abacus. https://drugpricinglab.org/tools/drug-abacus.

- 60.National Cancer Institute Research priorities. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/hardship/research.html

- 61.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, et al. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:308–312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Stage 2 Overview Tipsheet. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2Overview_Tipsheet.pdf.

- 64. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.002. Huo J, Yang M, Tina Shih YC: Sensitivity of claims-based algorithms to ascertain smoking status more than doubled with meaningful use. Value Health 21:334-340, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Barkowski S. Does employer-provided health insurance constrain labor supply adjustments to health shocks? New evidence on women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Health Econ. 2013;32:833–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dorland HF, Abma FI, Roelen CAM, et al. Work-specific cognitive symptoms and the role of work characteristics, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in cancer patients during 18 months post return to work. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2229–2236. doi: 10.1002/pon.4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:345–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neumark D, Bradley CJ, Henry M, et al. Work continuation while treated for breast cancer: The role of workplace accommodations. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2015;68:916–954. doi: 10.1177/0019793915586974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stergiou-Kita M, Pritlove C, van Eerd D, et al. The provision of workplace accommodations following cancer: Survivor, provider, and employer perspectives. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:489–504. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. ASCO Practice Central: Quality improvement library. https://practice.asco.org/quality-improvement/quality-programs/quality-training-program/quality-improvement-library.

- 71.Dusetzina SB. Drug pricing trends for orally administered anticancer medications reimbursed by commercial health plans, 2000-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:960–961. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]