INTRODUCTION

Payment for cancer care in the United States occurs in the context of a complex system of private and public health insurance coverage. As of 2017, approximately one half of Americans had employer-sponsored private health insurance, 7% were insured under private individual health plans, 21% under Medicaid, and 14% under Medicare.1 Another 9% of patients were uninsured, with substantial geographic variation, ranging from 3% in Massachusetts to 17% in Texas.1

These diverse health care payors are under substantial pressure to control spending on health care. The health care industry now constitutes approximately 18% of gross domestic product2 in the United States, representing $3.5 trillion in expenditures in 2017.3 Health care spending per capita in the United States is approximately twice as high as in comparable high-income countries.4 The cost of cancer care, which has been projected to reach up to $173 billion annually by 2020 (approximately 5% of total health costs),5 represents an important component of health spending.

Requiring that patients seek care from contracted providers within a network of providers offering negotiated rates is one strategy used by insurers to control costs.6-8 This practice may be one of few available in the context of an Affordable Care Act (ACA) requirement that qualified health plans be issued and priced equivalently for all individuals without regard to preexisting medical conditions.9 However, concerns have been raised about the narrow provider networks that can result from this strategy. Narrow networks offer a limited selection of providers in a given geographic area, sometimes defined as 25% or less of all area providers.10 Up to one half of the plans available on the marketplaces established by the ACA and more than one third of Medicare Advantage plans offer narrow networks.9,11 Narrow provider networks may in some cases promote coordinated care delivery, particularly if they include providers who are affiliated with well-integrated health systems12,13; however, even well-integrated health systems may not consistently outperform more traditional practice arrangements with respect to either care quality14,15 or cost.16

Since access to tertiary and specialty care is not an explicit component of the definition of essential health benefits within qualified health plans under the ACA,17 narrow provider networks could potentially discourage enrollment and limit access for patients who are in need of complex specialty care, including those with cancer.14 The objective of this report was to review the structure of provider networks, the regulations governing them, and the implications for patients with cancer who must navigate them.

PROVIDER NETWORK STRUCTURES

Payors commonly offer access to health care providers in the context of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) or preferred provider organizations (PPOs).18 Patients who are enrolled in an HMO are incentivized to obtain all covered care, other than emergency care, from an in-network provider. Such providers may either be independent practitioners or employed by a managed care plan.19 Patients who seek care outside the HMO’s network of providers may be responsible for the entirety of the costs of this out-of-network care. Patients with HMO plans generally require referrals from their primary care physicians to see specialists, which confers a gatekeeping role on primary care providers. HMOs constitute a common structure across private employer-sponsored plans, representing 16% of covered workers in 2018.20 Currently, approximately one third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in private Medicare Advantage plans, and 62% of Medicare Advantage enrollees had an HMO plan in 2019.21 Up to 82% of Medicaid enrollees are enrolled in state-managed care organizations,22 which generally use an HMO or similar primary care case management model.23,24

Plans with PPO networks generally charge higher premiums than those with HMOs but provide enrollees with greater flexibility with respect to providers. Within a PPO, patients may seek care from both in-network (preferred) and out-of-network (nonpreferred) providers, but they typically face additional out-of-pocket costs if they seek care out of network.25 In particular, when patients with PPO plans seek care out of network, this care does not necessarily count toward the statutory annual out-of-pocket maximums for private health plans established by the ACA. These maximums—$7,900 per individual and $15,800 per family in 2019—provide some protection against catastrophic costs incurred through treatment of unexpected serious illness. PPO plans may choose to offer out-of-pocket maximum limits for out-of-network care, but an increasing proportion do not,26 which potentially leaves patients exposed to large out-of-pocket expenses for out-of-network care, particularly if providers engage in balance billing—charging patients for any portion of fees not covered by the health plan.

In 2018, 49% of covered workers in employer-sponsored plans were enrolled in PPOs.20 Other provider network structures include point-of-service plans, which are similar to PPOs but may require referrals for specialist visits, and exclusive provider organizations, which are similar to HMOs in that out-of-network care may not be covered but which may not require referrals for specialist visits.25

Over the last decade, there has been a substantial increase in the prevalence of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs).27 As of 2019, these constitute any insurance plan that requires that individuals pay at least $1,350 for an individual or $2,700 for a family before the plan begins to provide financial coverage.28,29 HDHPs may be combined with tax-advantaged health savings accounts; the combination of an HDHP and a health savings account is often termed a consumer-directed health plan.30 The goal of HDHPs is to encourage cost-conscious consumer behavior in health care. Nevertheless, plans with this payment structure have been associated with significant financial burdens for patients.27 HDHPs are not synonymous with any particular provider network structure.

REGULATIONS GOVERNING PROVIDER NETWORKS

Historically, regulation of private health insurance plans was largely a matter of state law. Some states required only that provider networks be qualitatively “adequate,” without defining “adequate.” Others defined quantitative standards with respect to distance to providers, patient-to-provider ratios, and wait times for services.9 Similarly, Medicaid managed care programs were regulated at the state level, and Medicaid provider network standards were highly variable.31 The national Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) strengthened its oversight of state Medicaid provider networks in 2016, requiring that states define standards with respect to travel time and distance to care32; however, alterations to these requirements, including returning more oversight to states, are now under consideration.33 CMS also regulates Medicare Advantage network adequacy, defining minimum standards with respect to the number of in-network providers, ratios of providers to patients, and travel time and distance.34

For private health plans, the ACA codified federal requirements that qualified plans offer networks that ensure sufficient choice of providers to facilitate access without unreasonable delays, as well as provide publicly available provider directories.17,35,36 At the federal level, there are no quantitative definitions of sufficient choice or unreasonable delay. For patients with cancer—and particularly for those with rare or complex cases—these regulations are particularly salient; ready access to specialists with relevant expertise is not necessarily guaranteed. States retain an important role in regulating private plan networks, and requirements around provider-to-enrollee ratios, frequency of network directory updates, and travel time and distance still vary by state.35

Simultaneously, short-term health plans are becoming more prominent. Historically, these plans have offered coverage for, at most, 3 months at a time. They do not necessarily cover the essential health benefits required by the ACA, such as prescription drugs or maternity and mental health care,17 and as such do not fulfill the ACA’s individual mandate for coverage to avoid a tax penalty. Unlike qualified health plans, short-term plans can exclude coverage of preexisting conditions and set premiums on the basis of on a patient’s medical history. Given these restrictions, short-term plans frequently have lower premiums than qualified health plans.37 However, short-term plans are not subject to the ACA’s network adequacy requirements. Some may not even offer specific provider networks at all. Among those plans without specific networks, coverage for services can be variable, leading to high out-of-pocket costs for patients.38 Patients who are diagnosed with a serious illness while insured by a short-term plan may therefore confront major challenges in accessing necessary care. Recent federal policy shifts, including eliminating the tax penalty for foregoing qualified health plan coverage and allowing short-term plans to be purchased for up to 12 months,39 seem to be intended to encourage enrollment in these plans. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that up to 5 million more individuals will enroll in this type of plan over the next decade as a result of these policy changes, approximately 80% of whom would otherwise have enrolled in conventional plans.40

Given the increasing prevalence of narrow networks and short-term plans, patients increasingly may encounter out-of-network providers without realizing that those providers are not in network. This issue of resulting surprise billing for out-of-network care has become more prominent over the last decade. In 2011, 8% of individuals with private insurance used out-of-network care, and 40% of such care involved a surprise bill.41 In 2014, up to 20% of hospital admissions that originated in emergency departments led to an unexpected bill for out-of-network care.42 The impact of surprise bills can be substantial enough to lead patients to switch hospitals for subsequent care.43 Surprise bills may also be a particular challenge in light of the increasing prevalence of HDHPs.20 Patients with HDHPs may be responsible for the entire cost of their care until a deductible is met, and for patients with plans that cover some out-of-network care, their in-network and out-of-network deductibles may be different. As of 2018, nine states had adopted laws that provide protection from surprise billing, although these laws do not apply to self-insured employer plans that are regulated by the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act or to Medicare or Medicaid.44 At the time of this writing, the US Congress is actively considering federal legislation to address the surprise billing issue.45

PROVIDER NETWORKS AND CANCER CARE DELIVERY

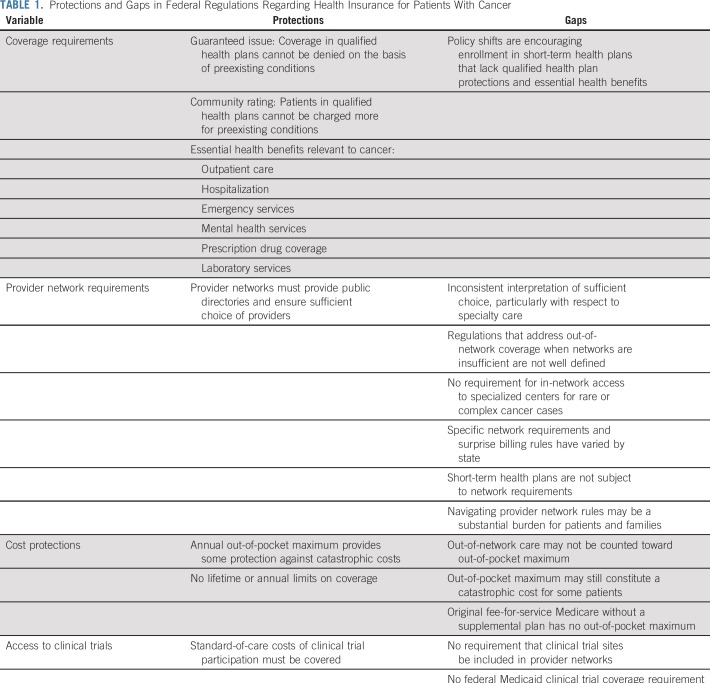

Key federal regulations, protections, and gaps regarding health insurance plans for patients with cancer are summarized in Table 1. For insured patients with cancer who have qualified health plans or public insurance, provider network requirements should, at minimum, enable in-network access to oncologic care. Still, a cancer diagnosis confers specific challenges with respect to insurance network adequacy, including access to specialized centers and investigational clinical trials.46

TABLE 1.

Protections and Gaps in Federal Regulations Regarding Health Insurance for Patients With Cancer

Access to Specialized Centers

Depending on diagnosis, geography, and individual preference, patients may wish to seek care at specialized cancer centers or from hospitals with specific expertise in their diseases. Some evidence suggests that care at specialized centers, such as those designated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), may be associated with improved outcomes for certain types of cancer.47-51 However, care provided at such centers, some of which are exempt from the prospective payment system used by CMS to determine reimbursement for hospitalizations by diagnosis and may therefore have less incentive to control costs,52 can be more expensive than care provided in local communities. This may create incentives for insurers to exclude specialized cancer centers from their networks.46 Indeed, only 41% of provider networks that were initially available on federal marketplace plans included NCI-designated cancer centers,53 and narrow networks seem to be more likely to exclude oncologists who are affiliated with centers designated by NCI or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.14

Access to Clinical Trials

Before the Affordable Care Act, requirements for insurance coverage for standard-of-care, or routine, costs of clinical trial participation varied by state. Medicare instituted a requirement for coverage of these costs in 2000,54 and from 2000 to 2010 many states followed suit.55 The ACA then instituted the first federal requirement for coverage of these costs within private insurance plans.56 There is currently no federal requirement for clinical trials coverage under Medicaid, though some states require such coverage.

Despite these requirements, provider network structure may constitute a barrier to enrollment in clinical trials. Although insurance plans may be required to cover routine care costs for clinical trial participants, there is no specific requirement that plans provide in-network access to centers or practices that maintain clinical trial programs. As described above, obtaining care out of network can be expensive. If covered at all, such care may require substantial additional cost sharing,57 and it may not count toward a catastrophic annual limit on out-of-pocket costs. Even if a patient’s insurance plan provides for out-of-network access to clinical trials in the absence of an equivalent in-network option, the additional logistical requirements to obtain approval for care at an out-of-network site could constitute an important barrier.

Patient Understanding of Provider Network Rules

The complexity of regulations described above may pose a particular challenge for patients with cancer, who must navigate the health care system while dealing with a life-threatening illness. Even in the absence of a cancer diagnosis, choosing insurance plans and understanding the implications of these choices can be an important challenge. Individuals shopping for insurance may focus predominantly on premium and overall cost rather than on provider networks,58-60 and narrow network structures may be associated with lower premiums. In this context, patients who are subsequently diagnosed with cancer—rarely an event that a patient would have expected when choosing an insurance plan—may be surprised to learn that their insurance plans do not cover access to preferred oncologists or cancer centers.

OPTIMIZING ACCESS TO AFFORDABLE CANCER CARE

If narrow provider networks may restrict access to specialized care that could improve outcomes, an important policy question is whether insurers should be required to provide access to tertiary care if a network contains an insufficient number or type of specialists. This may be difficult to implement, as such centers may be geographically distant and because such a requirement would likely diminish leverage for payors in contract negotiations with specialized, expensive centers, driving up the costs of care. Requiring payors to include such centers might be a disincentive for payors to participate in individual insurance marketplaces,61 potentially encouraging the spread of even more limited short-term plans that would not be subject to such requirements. Furthermore, patients who are in need of routine treatment of common cancers may not require access to highly specialized centers. Narrow network plans might reasonably limit providers for common cancers when the network includes multiple highly qualified specialists, but policy efforts may be needed to define the clinical criteria for treatment at specialized centers for which coverage mandates for payors might be proposed. Development of guidelines that define the qualifications for access to specialty care for rare or complex conditions would obviate the prevailing system of case-by-case adjudication and appeals, which are onerous for patients with cancer and their families to navigate. When the care required is highly specialized, as in the case of rare cancers that require complex surgical care, stem-cell transplantation, or novel cellular therapies, narrow network plans should have policies in place for exceptions that allow for coverage of otherwise out-of-network care.

Increasing awareness of health insurance plan structures among patients who are at risk for or diagnosed with cancer and their clinicians could assist patients in navigating a complex provider network landscape. As a cancer trajectory evolves, patients may become eligible for changes in insurance plans, either at their next open enrollment period or because of changes in life circumstances as a result of medical or financial toxicities. Financial and oncology nurse navigators play an important role in assisting patients with financial navigation, including navigating health insurance barriers to care.62 Particularly in settings in which navigation resources are not readily available, it is incumbent on oncologists to have a basic understanding of the regulations governing insurance networks so that they may advise patients appropriately. Clinicians should recognize and acknowledge the considerable burden that falls on patients and their families, who may spend a great deal of time negotiating with insurers on the extent to which services will be covered.

In conclusion, in an effort to control health care costs, insurers contract with in-network providers to deliver care at negotiated rates, restricting access to out-of-network providers by denying or reducing coverage. Patients with cancer and their caregivers already cope with anxiety and uncertainty surrounding a cancer diagnosis, symptoms of disease, and medical and financial toxicities63 of therapy. The need to navigate a complex health care system at the same time is likely a substantial challenge for many patients, who may not fully understand the implications of their health coverage choices with respect to options for care for serious illness—or who may not be able to afford the higher premiums charged by plans that offer more choice in providers. Policy efforts should focus on developing regulations that govern insurance plans that balance the dual goals of keeping health care affordable and optimizing access to cancer and other specialty care. In the meantime, patients and providers need access to clear information about the implications of their health insurance choices for access to cancer care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kenneth L. Kehl, Deborah Schrag

Financial support: Deborah Schrag

Administrative support: Deborah Schrag

Collection and assembly of data: Kenneth L. Kehl

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Insurance Networks and Access to Affordable Cancer Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jco/site/ifc.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Kenneth Kehl

Consulting or advisory role: Aetion

Deborah Schrag

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Merck (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Journal of the American Medical Association

Research Funding: Pfizer, American Association for Cancer Research (Inst), Grail (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: PRISSMM model is trademarked and curation tools are available to academic medical centers and government under creative commons license

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Imedex, Precision Medicine World Conference

Other Relationship: Journal of the American Medical Association

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation Health insurance coverage of the total population. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/

- 2.Moses H, III, Matheson DHM, Dorsey ER, et al. The anatomy of health care in the United States. JAMA. 2013;310:1947–1963. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, et al. National health care spending in 2017: Growth slows to post-Great Recession rates; share of GDP stabilizes. Health Aff (Millwood) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05085. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05085 [epub ahead of print on December 6, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer B, Cox C. How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries? Kaiser Family Foundation; https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinaiko AD, Landrum MB, Chernew ME. Enrollment in a health plan with a tiered provider network decreased medical spending by 5 percent. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:870–875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polsky D, Cidav Z, Swanson A. Marketplace plans with narrow physician networks feature lower monthly premiums than plans with larger networks. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1842–1848. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillen EM, Hassmiller Lich K, Trantham LC, et al. The effect of narrow network plans on out-of-pocket cost. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:540–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannelli J, Lucia K, Corlette S. Regulation of health plan provider networks. Health Aff (Millwood) https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20160728.898461/full/ 10.1377/hpb20160728.898461 .

- 10.Polsky D, Weiner J. The skinny on narrow networks in health insurance marketplace plans. The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics; http://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/skinny-narrow-networks-health-insurance-marketplace-plans [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson G, Rae M, Neuman T, et al. Medicare Advantage: How robust are plans’ physician networks? Kaiser Family Foundation; https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-advantage-how-robust-are-plans-physician-networks-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. Narrow networks and the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314:669–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasaitis L, Bekelman JE, Polsky D. Relation between narrow networks and providers of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3131–3135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JI, Huang BZ, Wu BU. Impact of integrated health care delivery on racial and ethnic disparities in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2018;47:221–226. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Check DK, Albers KB, Uppal KM, et al. Examining the role of access to care: Racial/ethnic differences in receipt of resection for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer among integrated system members and non-members. Lung Cancer. 2018;125:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaye DR, Min HS, Norton EC, et al. System-level health-care integration and the costs of cancer care across the disease continuum. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e149–e157. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.027730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. 111th US Congress. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010. https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- 18.Weiner JP, de Lissovoy G. Razing a Tower of Babel: A taxonomy for managed care and health insurance plans. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1993;18:75–103, discussion 105-112. doi: 10.1215/03616878-18-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold MR, Hurley R, Lake T, et al. A national survey of the arrangements managed-care plans make with physicians. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1678–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser Family Foundation 2018 employer health benefits survey. https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-summary-of-findings/

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation Medicare Advantage. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/

- 22.Kaiser Family Foundation Total Medicaid managed care enrollment. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mc-enrollment

- 23.National Council on Disability An overview of Medicaid managed care. https://www.ncd.gov/policy/chapter-1-overview-medicaid-managed-care

- 24.Kaiser Family Foundation Medicaid managed care market tracker. https://www.kff.org/data-collection/medicaid-managed-care-market-tracker/

- 25.Andrews M. HMO, PPO, EPO: How’s a consumer to know what health plan is best? Kaiser Health News; https://khn.org/news/hows-a-consumer-to-know-what-health-plan-is-best/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hempstead K. This year’s model: PPOs in 2016 offer less out-of-network coverage. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/12/2016-ppos-offer-less-out-of-network-coverage.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdus S, Selden TM, Keenan P. The financial burdens of high-deductible plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:2297–2301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Internal Revenue Service Health savings accounts and other tax-favored health plans. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p969

- 29.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services High-deductible health plans. https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/high-deductible-health-plan/

- 30.Fowles JB, Kind EA, Braun BL, et al. Early experience with employee choice of consumer-directed health plans and satisfaction with enrollment. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1141–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murrin S: State standards for access to care in Medicaid managed care. Department of Health and Human Services; https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-11-00320.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) programs; Medicaid managed care, CHIP delivered in managed care, and revisions related to third party liability. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/05/06/2016-09581/medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-programs-medicaid-managed-care-chip-delivered [PubMed]

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicaid program; Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) managed care. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/11/14/2018-24626/medicaid-program-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-plan-chip-managed-care

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Advantage network adequacy criteria guidance. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Advantage/MedicareAdvantageApps/Downloads/MA_Network_Adequacy_Criteria_Guidance_Document_1-10-17.pdf

- 35.Giovannelli J, Lucia K, Corlette S. Implementing the Affordable Care Act state regulation of marketplace plan provider networks. The Commonwealth Fund; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/may/state-regulation-of-marketplace-plan-provider-networks [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Department of Health and Human Services: 45 CFR Parts 155, 156, and 157 [CMS-9989-F] RIN 0938-AQ67 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Establishment of Exchanges and Qualified Health Plans; Exchange Standards for Employers. Federal Register, Volume 77, No. 59, Tuesday, March 27, 2012. [PubMed]

- 37.Pollitz K, Long M, Semanskee A, et al. Understanding short-term limited duration health insurance. Kaiser Family Foundation; https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/understanding-short-term-limited-duration-health-insurance/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goe C. Short-term plans: No provider networks lead to large bills for consumers. The Commonwealth Fund; https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/short-term-plans-large-bills-consumers [Google Scholar]

- 39.Internal Revenue Service Short-term, limited-duration insurance. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/03/2018-16568/short-term-limited-duration-insurance

- 40.Congressional Budget Office How CBO and JCT analyzed coverage effects of new rules for association health plans and short-term plans. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54915

- 41.Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. Out-of-network physicians: How prevalent are involuntary use and cost transparency? Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1154–1172. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garmon C, Chartock B. One in five inpatient emergency department cases may lead to surprise bills. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:177–181. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chartock B, Garmon C, Schutz S. Consumers’ responses to surprise medical bills in elective situations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:425–430. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker C. Counteracting surprise medical billing. National Conference of State Legislatures; http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/counteracting-surprise-medical-billing.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulman KA, Milstein A, Richman BD. Resolving surprise medical bills. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019 doi: 10.1377/hblog20190628.873493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schleicher SM, Mullangi S, Feeley TW. Effects of narrow networks on access to high-quality cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:427–428. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfson JA, Sun C-L, Wyatt LP, et al. Impact of care at comprehensive cancer centers on outcome: Results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2015;121:3885–3893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutierrez JC, Perez EA, Moffat FL, et al. Should soft tissue sarcomas be treated at high-volume centers? An analysis of 4205 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:952–958. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250438.04393.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung MC, Koniaris LG, Perez EA, et al. Impact of hospital volume on surgical outcome for head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1001–1009. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheung MC, Hamilton K, Sherman R, et al. Impact of teaching facility status and high-volume centers on outcomes for lung cancer resection: An examination of 13,469 surgical patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, et al. Impact of National Cancer Institute comprehensive cancer centers on ovarian cancer treatment and survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:940–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.US Government Accountability Office Payment methods for certain cancer hospitals should be revised to promote efficiency. https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/668605.pdf

- 53.Kehl KL, Liao KP, Krause TM, et al. Access to accredited cancer hospitals within federal exchange plans under the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:645–651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Coverage Determination (NCD) for routine costs in clinical trials (310.1) http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=1 [PubMed]

- 55.Mandated clinical trial coverage varies across states. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:31–32. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0714003. [No authors] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Society of Clinical Oncology Affordable Care Act and coverage of clinical trials: Frequently asked questions. http://www.asco.org/sites/default/files/faq_clinical_trials_coverage_statute.pdf

- 57.American Society of Clinical Oncology Summary of the Affordable Care Act statute regarding insurance coverage for individuals participating in approved clinical trials. http://www.asco.org/sites/default/files/aca_summary_clinical_trials.pdf

- 58.Arora V, Moriates C, Shah N. The challenge of understanding health care costs and charges. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:1046–1052. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.11.stas1-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blavin F, Karpman M, Zuckerman S. Understanding characteristics of likely marketplace enrollees and how they choose plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:535–539. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinaiko AD, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, et al. The experience of Massachusetts shows that consumers will need help in navigating insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:78–86. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schleicher SM, Aviki EM, Feeley TW. Helping patients with cancer navigate narrow networks. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3095–3096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spencer JC, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, et al. Oncology navigators’ perceptions of cancer-related financial burden and financial assistance resources. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1315–1321. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]