Highlights

-

•

Glittre-ADL test minimal important difference (MID) is −0.38 min in COPD patients.

-

•

Glittre-ADL test's MID reflects the changes in functional capacity.

-

•

Two tests are necessary for interpretation of changes induced by pulmonary rehabilitation.

Keywords: Pulmonary disease, Chronic obstructive, Rehabilitation, Activities of daily living, Exercise test, Outcome assessment

Abstract

Objective

To determine Glittre-ADL test minimal important difference in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Methods

This is quasi-experimental study. Sixty patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (age 64.1, SD = 9.09 years; forced expiratory volume in the first second 37.9, SD = 13.0% predicted participated in a pulmonary rehabilitation program based on physical training, conducted over 24 sessions supervised, three times a week, including aerobic training in treadmill and resistance training for upper limbs and lower limbs. The main outcomes were the Glittre-ADL test and six-minute walk test, before and after 24 sessions of pulmonary rehabilitation. The minimal important difference was established using the distribution and anchor-based methods.

Results

Patients improved their functional capacity after the pulmonary rehabilitation. The effect sizes of Glittre-ADL test and six-minute walk test improvement were similar (0.45 vs 0.44, respectively). The established minimal important differences ranged from −0.38 to −1.05. The reduction of 0.38 min (23 s) corresponded to a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 69% with an area under the curve of 0.66 (95%CI 0.51–0.81; p = 0.04). Subjects who achieved the minimal important difference of −0.38 min for the Glittre-ADL test had a superior improvement of approximately 42 m in the six-minute walk test when compared to patients who did not.

Conclusions

The present findings suggest −0.38 min as the minimal important difference in the time spent in the Glittre-ADL test after 24 sessions of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Trial registration: NCT03251781 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03251781)

Introduction

Functional limitation is a common and important finding in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)1 which is directly related to a reduction in quality of life,2 a higher frequency of exacerbations and hospitalizations3 and increased mortality.4 Therefore, it is an essential aspect of the evaluation routine of pulmonary rehabilitation programs (PRP).5

Field tests are functional status assessment tools capable of objectively assessing patient performance in common daily tasks.5 There are numerous valid tests for patients with COPD, and it is recommended to choose those with well-established measurement properties.6 When the objective is to verify the effect of an intervention, besides the choice of a responsive test, it is necessary to know its minimal important difference (MID), which allows a better interpretation of the results obtained after the intervention.7 The MID is defined as “a meaningful change or effect that might be considered important, beneficial or harmful, either by patients or informed proxies (including clinicians) and which would lead the patient/clinician to consider a change in management”.8 Among the most common functional capacity tests that present MID after PRP, may be highlighted: the six-minute walk test (6MWT),6 the Incremental Shuttle Walking Test6 and the five-repetition sit-to-stand test.9

However, although other tests have well-established measurement properties and are gaining space regarding the functional capacity assessment of patients with COPD, their MID has not been studied yet. In this context, there is the Glittre ADL-test (TGlittre), which is composed by multiple tasks common in daily life, developed, and validated specifically for patients with COPD.10, 11 It is valid10 and reliable for assessing the functional capacity of clinically stable patients10, 12, 13 and hospitalized patients.14 TGlittre is responsive to PRP10 and it is able to differentiate the functional capacity of patients with COPD from healthy individuals.15 Also, it correlates with several other instruments for assessing functional status10, 16, 17, 18, 19 and health status20 of patients with COPD.

Nevertheless, the minimal change required in the TGlittre after an intervention to determine clinically important improvement is still not known. Dechman and Scherer2 suggest that it is approximately 1 min, but it has not been formally tested and established. Therefore, the investigation of this response is relevant in order to evidence whether an intervention is capable of individually generating important changes in patient's capacity to perform multiple activities of daily living (ADL).21 This would facilitate the interpretation of the test results after a PRP.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to determine TGlittre MID in patients with COPD. Secondarily, we aimed to analyze the reliability and to compare the learn effect of the time spent in TGlittre pre and post PRP, as well as to investigate its responsivity after a PRP.

Methods

Subjects

Patients with COPD (GOLD II-IV)1 were referred to PRP of the Center for Assistance, Teaching and Research in Pulmonary Rehabilitation from the Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (NuReab-UDESC) and of the Research Group on Cardiopulmonary Interaction from the Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre (GPIC-UFCSPA). The inclusion criteria were: clinical diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry; age of 40 years or more and clinical stability in the four weeks prior to the protocol. Were excluded: active smokers, patients with any change in symptoms during the assessment protocol, PRP interruption for any reason, and patients with other respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, musculoskeletal and/or rheumatologic diseases that could compromise the performance of the evaluations, as well as the physical training established by the PRP.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research at UDESC (Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil), UFCSPA (Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), and Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre (Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) (CAAE 80831117.5.0000.0118, 1.413.342 and 836.248, respectively) and all participants signed the consent form. This study was registered and published in the Clinical Trials (NCT03251781).

Study protocol

Patients underwent pulmonary function assessment and, on two separate days, 6MWT and TGlittre. Both functional capacity tests were performed before and after 24 training sessions.

The pulmonary function test was performed according to the recommendations and criteria of acceptability and reproducibility proposed by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society.22 Spirometric measurements were obtained before and 15 min after the inhalation of 400 μg of salbutamol. The predicted values were calculated from the equation proposed for the Brazilian population.23

The TGlittre was executed according to the protocol validated by Skumlien et al.,10 which consists of performing five laps in the shortest possible time in a standardized circuit arranged in a 10-m corridor, carrying a backpack (2.5 kg for women and 5.0 kg for men). From the seated position, the subject stands up and walks along a flat corridor, in the middle of which there is a 3-step staircase (each step 17 cm high × 27 cm deep) to be climbed. At the end of the corridor, the subject moves three 1-kg objects, positioned on a shelf (shoulders’ height), one by one, to another shelf (waist's height) and then to the floor. Then the objects are placed back on the lower shelf, and finally returned to the upper shelf. The subject returns, in the reverse course, to the initial sitting position. Immediately after sitting down, another lap must be started, following the same circuit.10 Two tests were performed, with a minimum interval of 30 min or until the vital signs and symptoms returned to baseline. The test performed in the shortest time was used for the analysis.

The 6MWT was used as an anchor and performed as recommended by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society.24 Two tests were performed, with a minimum interval of 30 min or until the signs and symptoms returned to baseline. Before the test, patients were instructed to travel as far as possible, with standardized verbal encouragement every minute. The best performance was considered for the analysis. The MID of 30 m was considered as an anchor to determine the TGlittre's MID since it was established based on numerous studies.6

Pulmonary rehabilitation program

The PRP was designed according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.5 The supervised physical training was conducted over 24 sessions, three times a week. The program included continuous aerobic training on treadmill (30 min with training intensity determined by dyspnea sensation between 4 and 6 on the modified Borg scale)25 and resistance training for upper limbs with free weights or elastic bands (movements performed based on the modified diagonals of the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation method, performed in two sets, lasting 2 min each) and lower limbs training (quadriceps and triceps sural) with free weights and/or in the extensor chair (2 sets of 10–15 repetitions). Initially, lower limbs were exercised with 2-kg and upper limbs were exercised without any external workload. The localized training intensity was increased according to patient's perception of effort and difficulty (easy or difficult). If the exercise was “easy”, the load was increased by 1 kg for lower and 0.5 kg for upper limbs.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0 and GraphPad Prism 5. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to verify the distribution of the data. The Student's T for paired samples and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the time spent in TGlittre and the distance in 6MWT before and after PRP. The effect sizes of the change in TGlittre and 6MWT were calculated using Cohen's d statistics. The following classification was considered: small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5) or large (d ≥ 0.8) effect size.26 Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to analyze the reliability of TGlittre (ICC model: “two-way random”; ICC type: “absolute agreement”) and Student's T for paired samples or Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the learn effect of the time spent in TGlittre pre and post PRP. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation between the change in TGlittre and the change in 6MWT and, if there was a correlation ≥0.3,7 the MID of 30 meters for the 6MWT6 would be used as an anchor to determine the TGlittre's MID, using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The distribution-based methods used to calculate TGlittre's MID are listed in Table 1.26, 27, 28, 29 The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the change in distance walked in 6MWT between patients who achieved or not TGlittre's MID. The association between achieve the TGlittre's MID (yes/no) and achieve the 6MTWT's MID (yes/no) was tested with Chi-square test followed by Cramer's V to demonstrate the magnitude of the association. The significance level was 5%.

Table 1.

Distribution-based estimates of the minimal important difference (MID) and results.

| Method | MID calculation | MID (min) | MID (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM | SDbaseline * sqrt (1 − ICC) | −0.38 | 22.8 |

| Empirical rule effect size | 0.08 * 6 * SDΔ | −0.41 | 24.6 |

| Cohen's effect size | 0.5 * SDΔ | −0.43 | 25.8 |

| 0.5 times SD | 0.5 * SDbaseline | −0.84 | 50.4 |

| MDC | 1.96 * sqrt (2) * SEM | −1.05 | 63.2 |

MID, minimal important difference; SEM, standard error of measurement; SD, standard deviation; sqrt, square root; ICC, intraclass correlation coeficiente; Δ, difference in Glittre ADL-test (end − baseline rehabilitation); baseline, time in Glittre ADL-test at baseline; MDC, minimal detectable change.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated in MedCalc 17.1, aiming to achieve an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70.30 With a bidirectional α = 0.05 and β = 0.20, the estimated sample size was 60.

Results

From a total of 81 patients that engaged the study, 60 (37 men) completed the PRP. The reasons why 21 patients did not complete the PRP were: death (03); started smoking (01); withdrawal (07); severe COPD exacerbation (07); cataract surgery (02); diverticulitis (01). Table 2 shows patients’ baseline characteristics. Subjects improved their functional capacity after the PRP (Table 3), although 25 patients did not achieve the MID for the 6MWT (improvement ≥30 m). The effect sizes of TGlittre and 6MWT improvement were similar (Table 3). Patients who achieved the MID of 6MWT improved −0.33 min (95%CI −0.76 to −0.08 min; p = 0.038) more in TGlittre when compared to those that did not achieve.

Table 2.

Anthropometric characteristics and pulmonary function of the sample.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.1 ± 9.09 | 61.8–66.5 |

| Smoking history, pack-yearsa | 43.0 (37.5) | 43.3–59.2 |

| Body weight, kg | 70.2 ± 15.1 | 66.4–74.1 |

| Height, m | 1.65 ± 0.09 | 1.62–1.67 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 5.10 | 24.5–27.2 |

| FEV1/FVC, L | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 0.44–0.49 |

| FEV1, La | 1.01 (1) | 0.95–1.61 |

| FEV1, %pred | 37.9 ± 13.0 | 34.5–41.2 |

| FVC, L | 2.37 ± 0.77 | 2.17–2.57 |

| FVC, %preda | 70.1 (24) | 57.0–83.3 |

| GOLD II, n (%) | 12 (20%) | |

| GOLD III, n (%) | 31 (51.7%) | |

| GOLD IV, n (%) | 17 (28.3%) |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; kg, kilograms; m, meters; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; L, liter; %pred, percentage of predicted value. GOLD, spirometric classification of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Median (IQR).

Table 3.

Functional capacity improvement.

| Functional capacity improvement |

Effect size |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre rehabilitation (mean ± SD) |

Post rehabilitation (mean ± SD) |

Δ | p | Cohen's d | Mean difference/baseline SD | |

| TGlittre, min | 4.42 ± 1.69 | 3.67 ± 1.03 | −0.76 ± 0.86 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.45 |

| 6MWT, m | 443 ± 97.3 | 485 ± 101 | 42.4 ± .7 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.44 |

SD, standard deviation; Δ, post rehabilitation − pre-rehabilitation; TGlittre, Glittre-ADL test (Wilcoxon test); 6MWT, six-minute walk test (Student t test for paired samples); min, minute; m, meter.

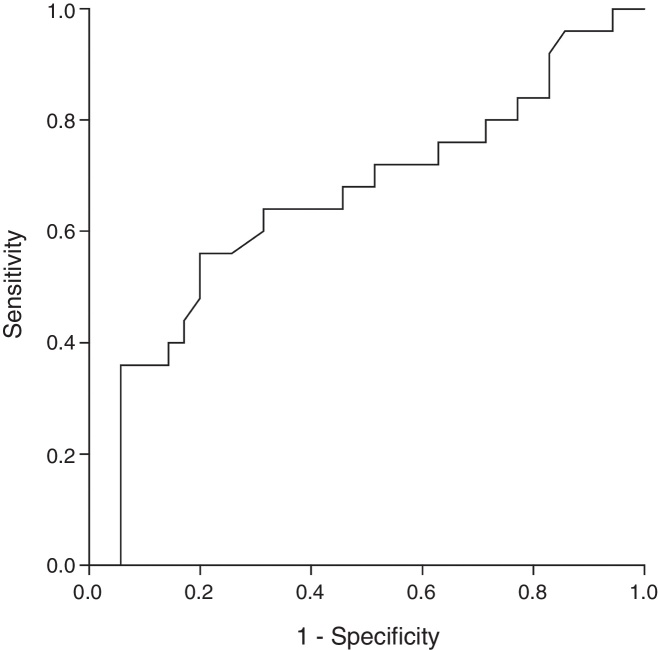

The baseline TGlittre and 6MWT presented a negative correlation (r = −0.78; p < 0.001), and the change in the TGlittre correlated with the change in the 6MWT (r = −0.31; p = 0.015); therefore, it was used as the reliable anchor.7 The ROC curve indicated a cutoff value for a clinically significant change in the TGlittre of −0.38 min, which is equivalent to 23 s (Fig. 1). This corresponded to a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 69% with an AUC of 0.66 (95%CI 0.51–0.81; p = 0.037).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for change in Glittre-ADL test using the improvement of 30 m in the six-minute walk test: AUC of 0.66 (95%CI 0.51–0.81; p = 0.037), sensitivity of 64% and specificity of 69%.

The different MID estimations using distribution-based techniques are summarized in Table 1. The MID ranged between a reduction of 0.38 and 1.05 min in the time spent during the TGlittre.

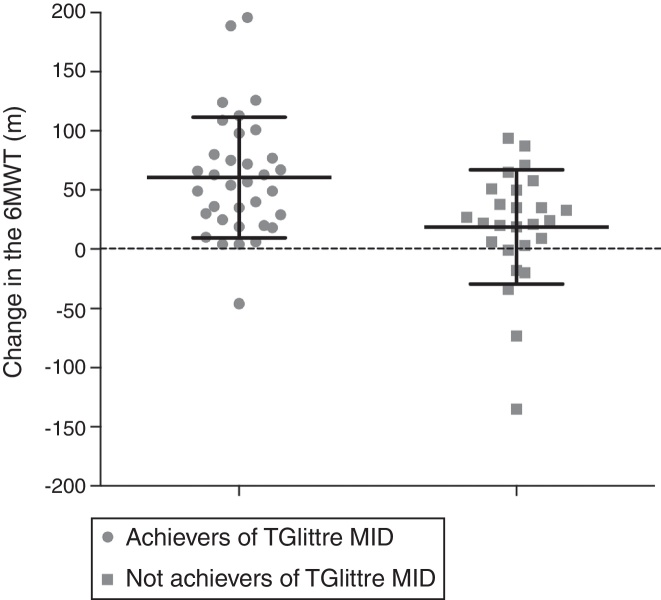

Subjects who achieved the MID of −0.38 min for the TGlittre had a superior improvement of approximately 42 meters in the 6MWT when compared to patients who did not (Fig. 2). Furthermore, there was an association between achieving the MID in 6MWT and in TGlittre (Cramer's V = 0.28; p = 0.028).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the change in six-minute walk test (6MWT) between subjects who did and did not achieve minimal important difference (MID) for Glittre-ADL test (TGlittre).

At baseline, the ICC between the first and the second TGlittre was 0.95 (95%CI 0.92–0.97), with a learning effect of 7.6%. This learning effect reduced to 4.6% after the pulmonary rehabilitation, with an ICC of 0.98 (95%CI 0.96–0.99). The mean difference between Δ pre-rehabilitation and Δ post-rehabilitation was −0.20 ± 0.70 min (p = 0.04).

Discussion

The present study established a MID of −0.38 min (−0.38 to −1.05 min) for the time spent in the TGlittre in patients with COPD after 24 sessions of pulmonary rehabilitation. Also, this MID proved to be able to differentiate patients regarding the 6MWT improvement.

The variation of the MID values found by the different distribution methods is expected since the patients may present different magnitudes of improvement after a PRP. The MID is considered the minimum value necessary for clinical changes.8 Therefore, it is recommended the use of the cut-off point of −0.38 min, obtained by the standard error of measurement (SEM) method and the ROC curve. However, since more severe patients tend to show greater improvement after PRP,31 the TGlittre's MID for them might be closer to −1.05 min. The simultaneous use of distribution and anchor-based methods were used in the present study.32 While distribution-based methods, such as the SEM, consider the psychometric and statistical properties of the instrument in the population of interest, the anchor-based method considers the change in other clinical relevant outcomes7, 32 and recognizes the importance of improving the patient's clinical status, which should be considered when evaluating the effect of an intervention.7

The results of this study, as in previous studies,10, 16 showed a strong negative correlation between time spent on TGlittre and distance walked in 6MWT in patients with COPD (r = −0.78 to −0.87; p < 0.05). It was expected to find similar results between the changes in the two tests after PRP. A possible explanation for the weak correlation found is that, despite evaluating the same functional status construct, TGlittre involves activities other than walking, that have not been specifically trained in PRP and that may induce limiting symptoms in different levels. A recent study from our group demonstrated that physiological responses differed among TGlittre's multiple tasks, and despite walking and moving objects on the shelf induced similar physiological responses, 63% of patients reported greater difficulty in performing the task of the shelf.33 This task may involve squatting or bending over, that are not specifically trained in the PRP, beyond elevation of unsupported upper limbs. Although the upper limbs training included in our PRP protocol has been shown to be effective in improving their endurance,34 its effect on the performance of ADLs are still contradictory.35, 36 Therefore, although they measure the same construct of functional status and both instruments show responsiveness to pulmonary rehabilitation with similar effect sizes, TGlittre may be more specific than 6MWT to identify an improvement in the ability to perform ADLs other than walking. It may also explain why the AUC, sensitivity and specificity of the ROC curve were relatively low. Although there is no consensus in the literature regarding ideal sensitivity and specificity values, an AUC above 0.7 is considered acceptable.30 In our study, we found an AUC slightly smaller. Thus, the cut-off point determined by the ROC curve may have low accuracy. However, it does not invalidate the MID found, since −0.38 min was also the lowest value found by the distribution methods.

Skumlien et al.10 reported that TGlittre is responsive to PRP because the mean difference in the test after an intervention was higher than the learning effect found in the study (−0.89 95%CI −0.48 to −1.30 vs. −0.33 min 95%CI −0.20 to −0.54). However, so far, no study had investigated the effect size of the TGlittre and whether the change in it after PRP was associated with a difference in similar outcomes. The present study demonstrated that TGlittre had an effect size similar to the 6MWT and that the value based on Cohen's d was high.26 The reliability and learning effect of TGlittre had also been investigated in previous studies, which demonstrated results similar to ours (ICC 0.95–0.97; learning effect: 6.3–7.6%).10, 12, 13 Meanwhile, our study was the first to demonstrate that the learning effect of TGlittre after PRP was about 40% lower than the baseline learning effect. In other words, to perform only one test can overestimate the effects of PRP. Therefore, it is recommended to use the MID of −0.38 min only in situations where TGlittre is applied twice.

As far as we know, this is the first study to identify the MID for TGlittre in patients with COPD. The MID of TGlittre will allow the interpretation of the results after a PRP, supporting its use in clinical practice. Improving functional status is one of the main goals of pulmonary rehabilitation.5 So, knowing the MID of TGlittre may help to identify whether or not the patients improved the ability to perform multiple ADLs after a PRP. In addition, the TGlittre MID may be used to determine the ‘number needed to treat’ in future intervention studies. Some limitations may be mentioned in this study. The use of an instrument that evaluates the perception of improvement by the patient as an anchor, which is widely recommended in the literature, could provide a MID that reflects changes in the patient's daily life. However, this perception is subjective and is not always associated with a change in objective measures. Thus, we have chosen an accurate, widely used and recommended functional capacity assessment tool. Another possible limitation is that the present study included patients with COPD from only two pulmonary rehabilitation centers, which may prevent the generalization of the results. However, we included patients with different degrees of disease severity (GOLD II-IV), which reflects the profile of patients normally included in studies from other centers.5 Finally, although the MID of −0.38 min was able to differentiate the change in functional capacity assessed by the 6MWT in the present sample, further studies are suggested to demonstrate the validity of this cutoff point in an independent sample.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the TGlittre is responsible for a PRP and its minimal important difference is −0.38 min (−0.38 to −1.05 min). It is recommended to use this minimal important difference only in situations where TGlittre is applied twice, since the learning effect of TGlittre after PRP was about 40% lower than the baseline learning effect. It is suggested that further studies are conducted to determine a TGlittre's minimal important difference for functional worsening.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior – CAPES/Brazil and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq/Brazil (Chamada Universal – MCTI/CNPq No. 14/2014) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina – FAPESC/Brazil (PAP UDESC Chamada Publica No. 01/2016. Grant number 2017TR645).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those who supported the data acquisition, to the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina – FAPESC/Brazil and to all the pulmonologists who referred their patients to the study protocol.

References

- 1.GOLD . 2018. From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Available from: http://goldcopd.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dechman G., Scherer S.A. Outcome measures in cardiopulmonary physical therapy: focus on the Glittre ADL-test for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2008;19(4):115–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitta F., Troosters T., Probst V., Spruit M., Decramer M., Gosselink R. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2006;129(3):536–544. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Aymerich J., Lange P., Benet M., Schnohr P., Anto J.M. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–778. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spruit M.A., Singh S.J., Garvey C. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S.J., Puhan M.A., Andrianopoulos V. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1447–1478. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revicki D., Hays R.D., Cella D., Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brozek J.L., Guyatt G.H., Schunemann H.J. How a well-grounded minimal important difference can enhance transparency of labelling claims and improve interpretation of a patient reported outcome measure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:69. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones S.E., Kon S.S., Canavan J.L. The five-repetition sit-to-stand test as a functional outcome measure in COPD. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1015–1020. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skumlien S., Hagelund T., Bjortuft O., Ryg M.S. A field test of functional status as performance of activities of daily living in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2006;100(2):316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes-Andrade A.A., Britto R.R., Soares D.C.M., Velloso M., Pereira D.A.G. Evaluation of the Glittre-ADL test as an instrument for classifying functional capacity of individuals with cardiovascular diseases. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(5):321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos K., Gulart A.A., Munari A.B., Cani K.C., Mayer A.F. Reproducibility of ventilatory parameters, dynamic hyperinflation, and performance in the Glittre-ADL test in COPD patients. COPD. 2016;13(6):700–705. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1177007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tufanin A., Souza G.F., Tisi G.R. Cardiac, ventilatory, and metabolic adjustments in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients during the performance of Glittre activities of daily living test. Chron Respir Dis. 2014;11(4):247–255. doi: 10.1177/1479972314552805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.José A., Dal Corso S. Reproducibility of the six-minute walk test and Glittre ADL-test in patients hospitalized for acute and exacerbated chronic lung disease. Braz J Phys Ther. 2015;19(3):235–242. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrêa K.S., Karloh M., Martins L.Q., dos Santos K., Mayer A.F. Can the Glittre ADL test differentiate the functional capacity of COPD patients from that of healthy subjects? Braz J Phys Ther. 2011;15(6):467–473. doi: 10.1590/s1413-35552011005000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karloh M., Karsten M., Pissaia F.V., de Araujo C.L., Mayer A.F. Physiological responses to the Glittre-ADL test in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(1):88–94. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulart A., Santos K., Munari A., Karloh M., Cani K., Mayer A. Relationship between the functional capacity and perception of limitation on activities of daily life of patients with COPD. Fisioter Pesq. 2015;22(2) [Google Scholar]

- 18.dos Santos K., Karloh M., de Araujo C., D’Aquino A., Mayer A. Relationship between the functional status constructs and quality of life in COPD. Fisioter Mov. 2014;27(3):361–369. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karloh M., Araujo C.L., Gulart A.A., Reis C.M., Steidle L.J., Mayer A.F. The Glittre-ADL test reflects functional performance measured by physical activities of daily living in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(3):223–230. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulart A.A., Munari A.B., Queiroz A.P.A.D., Cani K.C., Matte D.L., Mayer A.F. Does the COPD assessment test reflect functional status in patients with COPD? Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(1):37–44. doi: 10.1177/1479972316661924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holland A., Hill C., Rasekaba T., Lee A., Naughton M., McDonald C. Updating the minimal important difference for six-minute walk distance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M.R., Hankinson J., Brusasco V. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira C.A., Sato T., Rodrigues S.C. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(4):397–406. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132007000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland A.E., Spruit M.A., Troosters T. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1428–1446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nici L., Donner C., Wouters E. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(12):1390–1413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1211ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyrwich K.W., Tierney W.M., Wolinsky F.D. Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(9):861–873. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyrwich K.W., Nienaber N.A., Tierney W.M., Wolinsky F.D. Linking clinical relevance and statistical significance in evaluating intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Med Care. 1999;37(5):469–478. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norman G.R., Sloan J.A., Wyrwich K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hajian-Tilaki K. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for medical diagnostic test evaluation. Caspian J Intern Med. 2013;4(2):627–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spruit M.A., Augustin I.M., Vanfleteren L.E. Differential response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: multidimensional profiling. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(6):1625–1635. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00350-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaton D.E., Boers M., Wells G.A. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14(2):109–114. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulart A.A., Munari A.B., Tressoldi C., Santos Kd, Karloh M., Mayer A.F. Glittre-ADL multiple tasks induce similar dynamic hyperinflation with different metabolic and ventilatory demands in patients with COPD. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2017;37:450–453. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKeough Z.J., Velloso M., Lima V.P., Alison J.A. Upper limb exercise training for COPD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD011434. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011434.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janaudis-Ferreira T., Hill K., Goldstein R.S. Resistance arm training in patients with COPD: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. 2011;139(1):151–158. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calik-Kutukcu E., Arikan H., Saglam M. Arm strength training improves activities of daily living and occupational performance in patients with COPD. Clin Respir J. 2015 doi: 10.1111/crj.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]