Summary

Background:

The variability in bleeding patterns among individuals with hemophilia A, who have similar FVIII levels, is significant and the origins are unknown.

Objective:

To use a previously validated mathematical model of flow-mediated coagulation as a screening tool to identify parameters that are most likely to enhance thrombin generation in the context of FVIII deficiency.

Methods:

We performed a global sensitivity analysis (GSA) on our mathematical model to identify potential modifiers of thrombin generation. Candidates from the GSA were confirmed by calibrated automated thrombography (CAT) and flow assays on collagen-TF surfaces at 100 s−1.

Results:

Simulations identified low-normal FV (50%) as the strongest modifier, with additional thrombin enhancement when combined with high-normal prothrombin (150%). Low-normal FV levels or partial FV inhibition (60% activity) augmented thrombin generation in FVIII-inhibited or FVIII-deficient plasma in CAT. Partial FV inhibition (60%) boosted fibrin deposition in flow assays performed with whole blood from individuals with mild and moderate FVIII deficiencies. These effects were amplified by high-normal prothrombin levels in both experimental models.

Conclusions:

These results show that low-normal FV levels can enhance thrombin generation in hemophilia A. Further explorations with the mathematical model suggest a potential mechanism: lowering FV reduces competition between FV and FVIII for FXa on activated platelet surfaces (APS), which enhances FVIII activation and rescues thrombin generation in FVIII-deficient blood.

Keywords: hemophilia A, factor V, factor VIII, hemostasis, hemorheology

Introduction

Hemophilia A is a genetic bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency in coagulation FVIII. Clinical categories are defined by FVIII plasma concentrations as mild (> 5%), moderate (1–5%), or severe (<1%). Within these categories, individuals with similar plasma protein levels can have different bleeding phenotypes [1]. Some variations in bleeding phenotype can be assigned to the mutations in the F8 gene, or thrombophilic mutations, but a large portion of them remain unexplained [2–4]. Plasma protein levels are potential modifiers of bleeding; the variability in coagulation factor levels is large, with the normal range regarded as 50–150% of the mean of the healthy population. We hypothesize that certain combinations of coagulation factor levels within this normal range enhance thrombin generation in the context of FVIII deficiencies. Identifying such combinations using a reductionist approach is unlikely to succeed since clot formation is a complex, nonlinear process. Here we use a mechanistic mathematical model of flow-mediated coagulation as a screening tool to predict modifiers of thrombin generation in FVIII deficiency and verify these predictions with experimental models. The model includes flow because it is intended to approximate the situation in which blood flows over a damaged vessel. Coagulation dynamics under flow are different from those in static experiments because of continual delivery of additional zymogens and platelets to the injury and the wash-out of fluid-phase proteins.

The coagulation reaction network shares many features with gene, metabolic, and protein networks, for which mathematical approaches are essential to predict system responses [5–7]. First, complex networks display nonlinear responses due to positive and negative feedback loops. In the coagulation network, thrombin enhances and inhibits its production through different pathways. Second, the interactions between components of complex networks must be fully described to mechanistically explain emergent properties of the network itself. For example, our models of coagulation under flow showed that thrombin generation had a threshold dependence on surface tissue factor (TF) concentration and this behavior was explained by the race between inhibition of TF activity due to physical coverage by adhering platelets and formation of the tenase complex on activated platelet surfaces [8–10]; the prediction of a threshold behavior under flow was later validated in experiments [11]. Other experimental studies under flow have shown threshold behavior in the initiation of coagulation that is dependent on injury size and flow rate, both being attributable to a physical mechanism based on the competition between reaction and transport of activated coagulation factors [12–15]. Finally, complex networks are robust in that they maintain phenotypic stability in the face of perturbations. Even with the variability in coagulation factor levels, the hemostatic response is robust, forming clots that prevent bleeding while maintaining vessel patency.

A powerful tool for analyzing the variability of a model network’s output is sensitivity analysis (SA); here, model inputs are altered one-at-a-time (local SA, LSA) or in combination (global SA, GSA), and the resulting influence on model outputs is studied [16]. One SA approach is to vary model input parameters to identify those to which the model output is the most sensitive. There are LSA studies that use this approach on models of coagulation in the absence of flow [17,18]. Another approach is to use the model to make predictions about potential outcomes given variations in the input, e.g., the inputs may represent variability in a disease state with the model predicting therapeutic outcomes [19,20]. We previously conducted a LSA and GSA to determine how normal variation (±50%) in plasma protein levels affected thrombin generation in a model of flow-mediated coagulation under healthy conditions [21]. This variation led to thrombin concentrations greater than 1 nM over 2–5 minutes, substantiating results from Danforth et al. [20] showing that normal variations in plasma proteins led to a normal range of thrombin output. These results underscore the robustness of thrombin generation under healthy conditions.

In this study, we are interested in identifying modifiers of thrombin generation when FVIII is deficient. Our approach was to first examine thrombin generation in a mathematical model to generate potential hypotheses that could be tested experimentally. We performed thousands of simulations in which FVIII was fixed at a low level but all other plasma proteins were allowed to vary. We then used the GSA as a screening tool to search for combinations of these levels that either enhanced or reduced thrombin generation. The combinations identified with the GSA to have the greatest effect were verified in whole blood flow assays and calibrated automated thrombography (CAT). This approach identified a potential mechanism where variations in FV levels within the normal range dramatically alter thrombin generation and fibrin formation in FVIII deficiencies.

Methods

Mathematical Model and Sensitivity Analysis

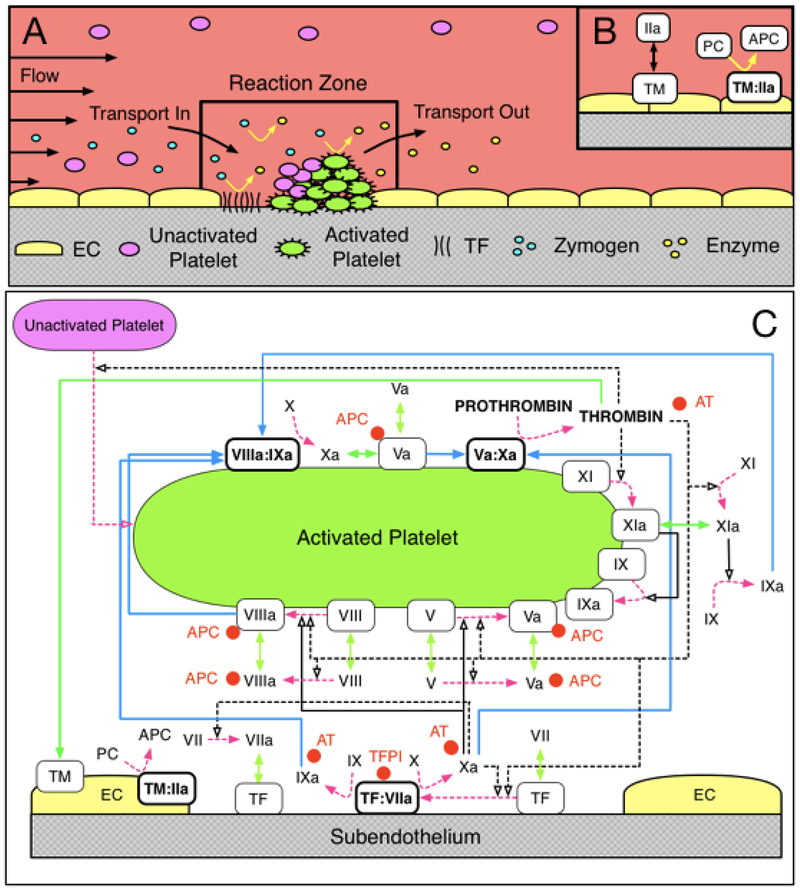

The mathematical model used in this work, and described in detail in our previous studies [8,9,22], simulates the clotting response under flow in a reaction zone (RZ) above a small vascular injury (≈100 μm2) where tissue factor (TF) in the subendothelium (SE) is exposed to flowing blood (Figure 1A,B). The height of the RZ as well as the rate of platelet and protein transport into and out of it depends on the shear rate and on the species’ diffusivities. Each species in the RZ is assumed to be uniformly distributed (well-mixed) and is described by its concentration, whose dynamics are tracked through an ordinary differential equation. The coagulation reactions (binding/unbinding from cellular surfaces, enzymatic activation, and inhibition) and platelet function are monitored in the RZ (Figure 1C). All reactions occurring in the plasma and on cellular surfaces (SE and activated platelet surfaces (APS)) are modeled using mass-action kinetics. Platelet activation occurs by contact with the SE and by exposure to soluble agonists (predominantly thrombin). Specifically, 1 nM of thrombin (concentration at which PAR1 mediates platelet activation [23]) activates platelets, leading to continued increases in thrombin [8–10,21]. In this model, platelet activation results in the release of platelet derived FV and exposure of binding sites for coagulation proteins involved in surface-bound reactions. Proteins bound to the SE or APS are stationary and not susceptible to removal by flow. The accumulation of activated platelets results in the harboring of surface-bound enzyme-cofactor complexes (FVIIIa:FIXa and FVa:FXa), and amplifying thrombin generation. Simultaneously, platelet deposition on the SE reduces the activity of SE-bound TF:VIIa, attenuating thrombin production by physically blocking TF:FVIIa activity. The inputs to this model are TF density, plasma protein levels (FII, FV, FVII, FVIIa, FVIII, FIX, FX, FXI, TFPI, AT), platelet count, kinetic rate constants, binding site numbers on APS, and flow rate; the available outputs are protein concentrations and platelet populations as a function of time [10,21]. All simulations in this study are performed at a TF density of 5 fmol/cm2, determined as a critical TF level, where thrombin sharply transitioned between an attenuated and amplified response and a shear rate of 100 s−1 based on previous flow assay studies with FVIII deficient blood at a similar TF density [24]. A GSA was performed by varying plasma protein levels between ±50% of normal. The analysis considers the impact of varying parameters simultaneously and uniformly over their full range of values and quantifies the sensitivity of the model output by its variance. Monte-Carlo sampling was used to explore parameter space and Sobol indices were used to attribute fractions of output variance to plasma proteins as previously described [21].

Figure 1. Schematic of coagulation reactions included in our model.

Schematic (A) of the reaction zone where platelet deposition and coagulation reactions are tracked, and (B) of the endothelial zone into which thrombin can diffuse from the reaction zone, and in which thrombin binds to thrombomodulin and produces activated protein C (APC) which can diffuse into the reaction zone. (C) Dashed magenta arrows show cellular or chemical activation processes. Blue arrows show chemical transport in the fluid or on a surface. Green segments with two arrowheads depict binding and unbinding from a surface. Rectangular boxes denote surface-bound species. Solid black lines with open arrows show enzyme action in a forward direction, while dashed black lines with open arrows show feedback action of enzymes. Red disks show chemical inhibitors.

Materials

Recombinant human tissue factor (RTF-0300), anti-human FV (AHV-5101, mouse, monoclonal, IgG1), human prothrombin (HCP-0010), human FV (HCV-0100), plasma immunodepleted of FV (FV-ID), and prothrombin (FII-ID) were from HTI (Essex Junction, VT). L-α-Phosphatidylserine (PS, brain, porcine) and L-α-phosphatidylchoine (PC, egg, chicken) were from Avanti (Alabaster, AL). Bio-Beads SM-2 (152–3920) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). TF ELISA (ab220653) and anti-human factor VIII (ab61370) was obtained from Abcam Inc (Cambridge, MA). Sodium deoxycholate was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). DiOC6, HEPES-NaOH, NaCl, NaN3, and methanol were from Sigma Aldridge (St. Louis, MO). Equine type I collagen was from Chrono-log (Chrono-Par Collagen, Havertown, PA). Human fibrinogen was from Enzyme Research Laboratory (South Bend, IN). FVIII deficient (<1%) plasma was from George King Biomedical (Overland Park, KS). Normal pooled plasma was made in-house from 22 unique donors ages 18–50. Alexa Fluor 555 protein labeling kit was from Thermo-Fisher (A20174, Waltham, MA). HEPES buffered saline (HBS, pH 7.4) contained 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl. Recalcification buffer was HBS with 75 mM CaCl2 and 37.5 mM MgCl2. Calibrated Automated Thrombogram (CAT) reagents were obtained from Diagnostica Stago.

Subject recruitment and blood collection

Subjects were recruited at the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Human whole blood was collected by venipuncture into 3.2% sodium citrate. Blood from three individuals with FVIII deficiency are referred to as Sample 1, 2, and 3 in Table S1. FVIII levels were determined the day of collection using a one stage clotting assay. At the time of diagnosis, these individuals had baseline FVIII levels of 3.0%, 7.5%, and 8.5% and bleeding scores [25] of 12, 12, and 7, respectively. The study and consent process received Institutional Review Board approval from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Tissue factor vesicles

TF was reconstituted in 20:80 PS:PC vesicles [26]. Vesicles were ±0.44 nm as measured by dynamic light scattering (Brookhaven Instruments, ZetaPALS). The concentration of TF was determined by ELISA to be 280 nM, giving a molar ratio for phospholipid:TF of 9285:1.

Whole blood flow assays

Type I collagen and TF vesicles were co-patterned in four spots (4 mm) on glass slides (25 mm × 75 mm) using PDMS microwells [24]. The microwells were filled with 10 μL of collagen (1 mg/mL) and incubated overnight at 4◦C. Wells were rinsed in triplicate and then 10 μL of TF vesicle suspension (2.8 nM) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature followed by a triplicate rinse of HBS. TF surface concentration was measured as 1.09 ± 0.2 fmol/cm2 [27]. Before perfusion, blood was incubated for 15 min at 37◦C with 1 μM DiOC6 and 60 μg/mL Alexa 555-fibrinogen (1:50 labeled:plasma fibrinogen) and as indicated with an anti-human FV function blocking antibody (100 μg/mL), prothrombin (50 μg/mL), or vehicle (Table S1). Recalcified (7.5 mM CaCl2, 3.75 mM MgCl2) whole blood was perfused at a wall shear rate of 100 s−1 through microfluidic channels (50 μm H × 500 μm W × 10 mm L) with a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, PhD Ultra). Platelet and fibrin(ogen) fluorescence were measured in each channel (IX83 Olympus, 40X, NA=0.6). The maximum fluorescence intensity and velocity were determined from custom Python scripts and normalized by the maximum for each donor (Figure S1).

Calibrated automated thrombography

Thrombin generation was measured with by Calibrated Automated Thrombogram (CAT, Thrombinoscope BV) using 5 pM TF, phospholipids, and calcium ions. Plasma samples with varying FV and prothrombin levels were prepared using plasma immunodepleted for FV or prothrombin. To achieve FV or prothrombin concentrations above 100% of normal, purified zymogens of interest were added. An anti-human FVIII antibody was used to model hemophilia A.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis analysis of the variance [28], followed by Dunn post hoc test to determine differences between pairs [29].

Results

Mathematical Model

Tissue Factor Distributions

Our previous studies revealed a critical TF level, where thrombin sharply transitioned between an attenuated and amplified response [8–10]. Under FVIII-deficient conditions and high TF, our model produces more than 1 nM of thrombin by 10 min, albeit at a decreased rate compared to normal FVIII levels [8]. Individuals with FVIII deficiencies bleed in regions of the body with low TF levels [30–32]. Taken together, these previous studies show that the TF level has an important influence on whether above 1 nM thrombin is produced for multiple values of plasma protein levels.

To identify modifiers of thrombin generation in the model under hemophilia A conditions, we first determined a range of critical TF levels so that minor decreases in that level resulted in less than 1 nM of thrombin and minor increases resulted in above 1 nM thrombin. For normal zymogen levels, our model produces 1 nM thrombin in ≈4 min [21], but thrombin production is much slower with 1% FVIII. We define an “amplified thrombin response” as a 1 nM thrombin concentration by 40 min. As an initial screen, we varied the plasma protein levels between 50% and 150% of their normal levels for both normal and FVIII-deficient blood (FVIII fixed to 100% or 1% of normal) using 2,500 Latin Hypercube samples [33]. For each of these parameter-set samples, a bisection procedure was used to determine the minimum TF level required to achieve an amplified thrombin response. The distribution of these values determined a critical range of TF levels over which the thrombin response was most sensitive to variations in plasma protein levels.

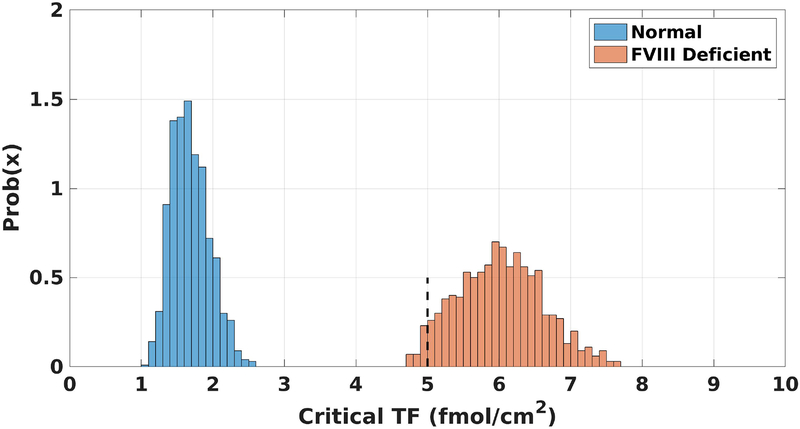

Figure 2 shows the TF distributions for normal and FVIII-deficient plasma where the other plasma protein levels were varied between 50–150%. No overlap between the two distributions is observed, with normal and FVIII-deficient plasma having a TF range of [1.07, 2.62] fmol/cm2 and [4.63, 7.78] fmol/cm2, respectively. These distributions suggest that a TF level of 5 fmol/cm2, near the left edge of the distribution for FVIII-deficient plasma, is a good choice for conducting further probes in a GSA because for the majority, but not all, of the plasma protein combinations that we tested, little thrombin was produced. All further simulations in this study were performed with TF at 5 fmol/cm2.

Figure 2. Critical TF distributions.

The probability density function for the necessary level of TF needed in the model for normal (blue) and FVIII deficient (orange) plasma to achieve an amplified thrombin response, i.e., 1 nM thrombin by 40 minutes. Dashed black line at 5 fmol/cm2 is the fixed TF level for all simulations in this work.

GSA identifies FV as a modifier of thrombin generation in hemophilia A

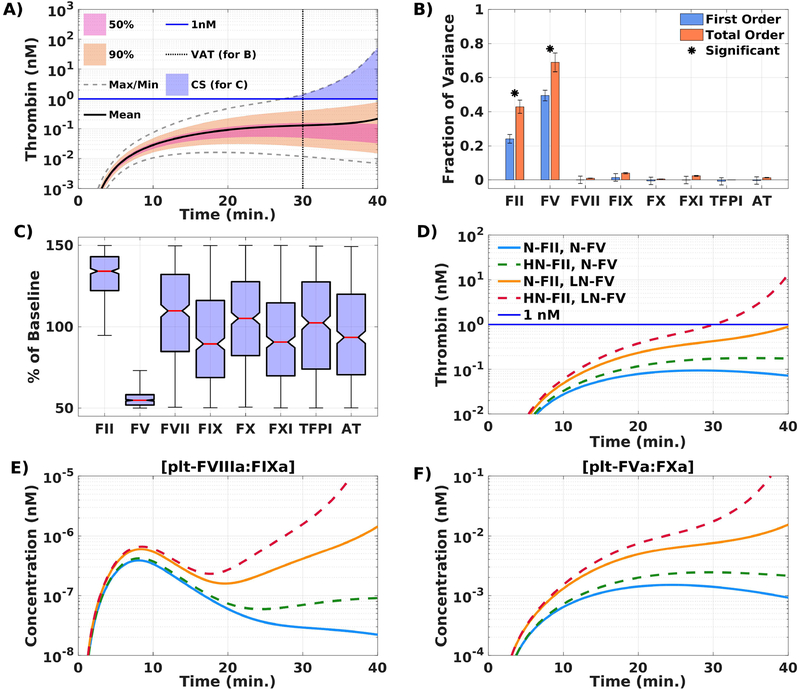

We performed a GSA of thrombin generation by varying plasma protein levels; we used 110,000 simulations; each plasma protein level (except FVIII, which was fixed to 1%), was sampled uniformly and independently between 50–150% of normal for each simulation. To characterize the thrombin concentrations that resulted from all of these simulations and the plasma level variations, we separated them into quantiles (Figure 3A). We distinguish simulations by those that led to 1 nM thrombin within 40 minutes and those that did not.

Figure 3. FV is a modifier of thrombin generation in a mathematical model of flow-mediated coagulation.

Global sensitivity analysis identifies FV as a modifier of thrombin generation. (A) Thrombin concentration time series generated by uniformly and independently varying plasma protein levels ± 50% from normal (110,000 total simulations); mean (solid black line), boundaries that encompass 50% (pink), and 90% of the data (orange), and the maximum/minimum of the computed solutions (gray-dashed); blue line drawn at 1nM. VAT = variance analysis time, CS = condition for samples. (B) First (blue) and total (orange) order Sobol indices are plotted as mean ± standard deviation computed with 5,000 bootstrap samples of the original 110,000 simulations. (C) Plasma protein levels distributions shown as box-and-whisker plots (mean in red, whiskers drawn at 3 times the interquartile range), conditioned on achieving more than 1nM of total thrombin by 40 min. Effects of specific variations in plasma levels of FII and FV on thrombin generation in the mathematical model. [“N” denotes normal (100%),“LN” denotes low-normal (50%), and “HN” denotes high-normal (150%) of the respective baseline plasma level; N-FII= 1400 nM, N-FV = 10 nM.] (D) Total thrombin; (E) platelet tenase (plt-FVIIIa:FIXa); (F) prothrombinase (plt-FVa:FXa); during a time course of 40 min. Description of labels are given in Table 1. All simulations performed at TF = 5 fmol/cm2.

To determine how each plasma level variation contributed to the variance in thrombin output, we performed a Sobol analysis [34]. Figure 3B shows the first order and total order Sobol sensitivity indices for the thrombin concentration at 30 min. A first order Sobol index assigned to a parameter represents the fraction of the variance attributable to that parameter alone while the total order index indicates the fraction due to that parameter plus its interactions with all other parameters. The plasma protein levels that had the most influence are FV and prothrombin (FII), which account for approximately 50% and 24% of the variance, respectively. In addition, approximately 19% of the model variance is explained by the interaction between prothrombin and FV, as indicated by their total order Sobol indices (69% and 43%) exceeding their first order indices.

The blue shaded region in Figure 3A shows the set of simulations that led to 1 nM thrombin within 40 min. We characterized this set of ≈5000 simulations by looking at their corresponding distributions of plasma protein levels (Figure 3C). Almost all of the plasma protein levels have medians close to 100% of normal with distributions that appear roughly uniform. This indicates that it is possible to achieve 1 nM thrombin by 40 min with many different combinations of these plasma levels within their prescribed ranges. The plasma FV and prothrombin levels are striking exceptions. Both have medians closer to the extreme values of their normal ranges and their distributions are much narrower than the other plasma protein levels. Although the prothrombin distribution is skewed toward higher levels, it does extend below 100%, indicating that higher than normal prothrombin is not strictly necessary to achieve 1 nM thrombin. Conversely, every sample that achieved 1 nM thrombin had plasma levels of FV that were strictly less than 75% of normal. Over 75% of these samples had a FV level less than 60% of normal. This indicates that low-normal FV levels enhances thrombin generation in FVIII-deficient plasma in this model of flow-mediated coagulation stimulated with low TF. As expected, sufficiently low FV levels (below 5% of normal) combined with low FVIII levels (1% of normal) produces little to no thrombin in the simulations (Figure S2).

Observation of low-normal FV leading to increased thrombin generation.

We used our mathematical model to isolate the effects of low-normal FV (50%) and/or high-normal prothrombin (150%) on thrombin production in FVIII-deficient plasma. Table 1 lists the cases of prothrombin and FV considered and Figure 3D shows their thrombin time-courses. In the two cases with low-normal FV, one with normal prothrombin and one with high-normal prothrombin, greater than 1 nM of thrombin is produced and thrombin generation occurs earlier with a high-normal prothrombin level. Less than 1 nM of thrombin is produced with normal levels of FV. These results support the idea that low-normal FV is key to enhancing thrombin production and suggest that high prothrombin levels alone are insufficient to significantly alter thrombin production. Figure 3E–F shows that lowering FV increases platelet-bound tenase and prothrombinase concentrations as early as 5 min, while there is little thrombin present.

Table 1.

Description of variations in FII and FV plasma levels.

| Label | Variation | |

|---|---|---|

| N-FII, N-FV | 100% FII (1400 nM), | 100% FV (10 nM) |

| N-FII, LN-FV | 100% FII (1400 nM), | 50% FV (5 nM) |

| HN-FII, N-FV | 150% FII (2100 nM), | 100% FV (10 nM) |

| HN-FII, LN-FV | 150% FII (2100 nM), | 50% FV (5 nM) |

Experimental Models

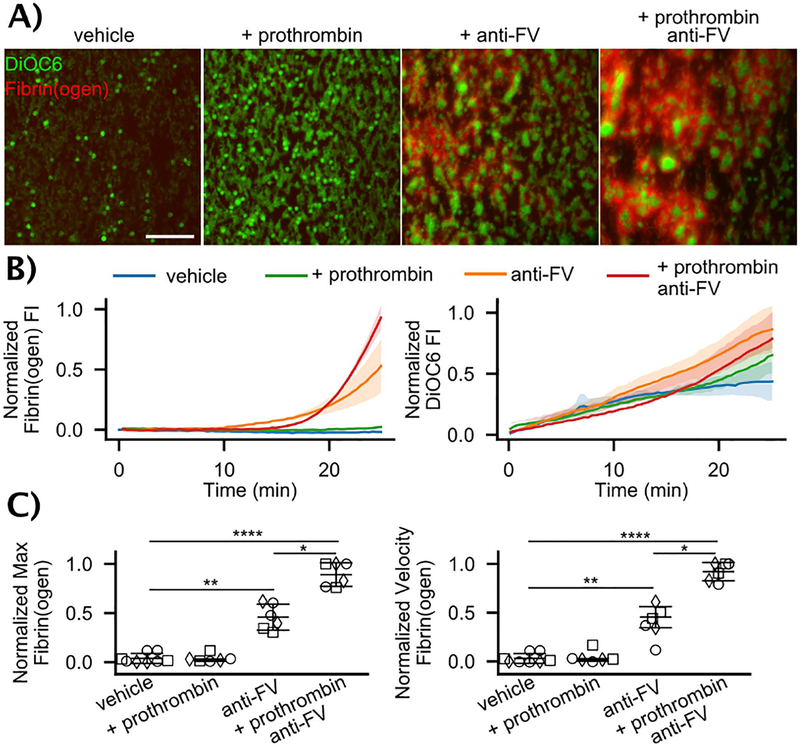

Partial inhibition of FV enhances fibrin deposition in FVIII-deficient blood under flow

Whole blood microfluidic assays were performed at 100 s−1 on type I collagen-TF. Blood from individuals with moderate and mild FVIII deficiencies (Table S1) was treated with exogenous prothrombin (50 μg/mL), an anti-FV antibody at a concentration that reduced FV activity to ~ 60% in normal pooled plasma (Figure S3), both exogenous prothrombin and anti-FV, or a vehicle control (Figures 4 and S4). In the vehicle and exogenous prothrombin cases, little to no fibrin was observed. Platelets adhered and nearly coated the surface over the 25 minute experiment, but there were no large, multilayer platelet aggregates. The anti-FV antibody alone supports fibrin formation in and around multilayer platelet aggregates, and when combined with prothrombin, the effect is even more pronounced with larger, platelet-fibrin thrombi. There was a significant increase in both the rate of and maximum accumulation of fibrin(ogen) with partial inhibition of FV (Figures 4B–C). There were no significant differences in total platelet accumulation despite the morphological differences (Figures 4B and S5). The FVIII levels in these samples were higher (3.0–8.5%) than those considered in the GSA analysis. Simulations predict that low normal FV boosts thrombin generation even at FVIII levels of 3–8% (Figure S6).

Figure 4. Flow assays with whole blood from FVIII deficient individuals.

(A) Representative images of DiOC6 labeled platelets and leukocytes and Alexa Fluor 555 labeled fibrin(ogen) on collagen-TF surfaces at 100 s−1 after 25 min for vehicle control, 50 μg/mL exogeneous prothrombin, 100 μg/mL anti-FV, and exogenous prothrombin and anti-FV. Scale bar = 50 μm. Individual fluorescent channels are found in Fig. S2. (B) Representative fibrin(ogen) and platelet/leukocyte accumulation dynamics in terms of normalized fluorescent intensity (FI). (C) Fibrin(ogen) normalized maximum fluorescence intensity and rate of deposition (normalized velocity) for FVIII levels of ○ = 3.0%, ☐= 7.5%, ◇ = 8.5%. See SI and Fig. S8 for calculation of metrics. P-values represented as *, **, and **** for 10−2,10−4, and 10−7, respectively. Images are from a Olympus IX81 microscope driven by cellSens software and equipped with 16-bit CCD camera (Orca-R2, Hamamatsu) and a 40X air objective (NA 0.6).

Low-normal FV and partial inhibition of FV enhances thrombin generation in FVIII-inhibited or FVIII-deficient plasma

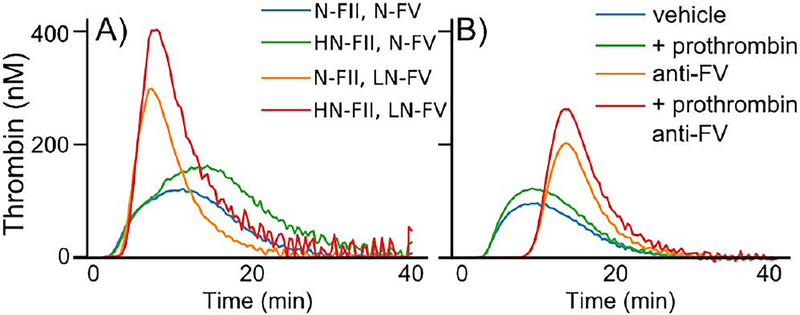

CAT was used to measure the effects of reducing FV levels or activity on thrombin generation [35]. We altered zymogen concentrations to approximate the four conditions in Table 1 using mixtures of FV and prothrombin depleted plasmas, purified FV and prothrombin, and an anti-FVIII function blocking antibody to yield FVIII activity of <1%. Note that thrombin concentration curves under static conditions have a peak because zymogens are depleted, but those under flow plateau because of continual replenishment of zymogens. With this in mind, Figure 5A and Table S2 show results consistent with the mathematical model’s predictions, low-normal FV (43%) increases the peak thrombin concentration and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP), which are both further enhanced when prothrombin (136%) is added. Similar trends were measured with FVIII deficient plasma using the same treatments as in the flow assay experiments (Table S2). Figure 5B shows results from FVIII deficient (<1%) plasma. Partial inhibition of FV increases thrombin peak concentration and ETP, with an even larger peak concentration when combined with high prothrombin (135%). The opposite trend in ETP was observed for pooled normal plasma where inhibition of FV reduced ETP in plasma with normal FVIII levels both with and without exogenous prothrombin, but the trend in peak value remained the same (Table S1). Notably, there is an increased lag time for treatments including the anti-FV antibody in FVIII-deficient plasma and pooled normal plasma. This observation could be due to the difference between inhibiting FV with an antibody compared to plasma deficient in FV.

Figure 5. Calibrated automated thrombography.

(A) FII and FV levels were varied using immunodepleted plasmas and purified FII and FV in the presence of an anti-FVIII function blocking antibody. ‘N’, ‘H’, and ‘L’ corresponds to normal, high, and low levels of the respective protein. (B) FVIII deficient (<10%) plasma treated with vehicle control, 50 μg/mL exogenous prothrombin, 100 μg/mL anti-FV, and exogenous prothrombin and anti-FV. All assays conducted with 5 pM TF and phospholipids. Tables S1 and S2 contain the measured prothrombin, FV, and FVIII levels corresponding to each curve.

A potential mechanism by which lowering FV enhances thrombin generation in FVIII-deficient blood

The mechanisms underlying enhanced thrombin generation with low FV in the mathematical model simulations are described in this section. Future study is needed to confirm these mechanisms experimentally.

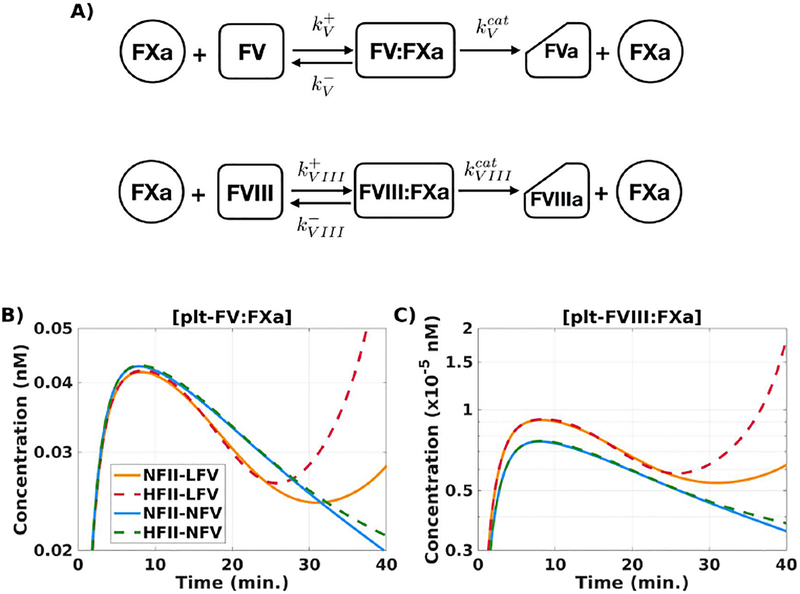

Substrate competition for FXa

Platelet-bound FV (plt-FV) and FVIII (plt-FVIII) are both substrates for platelet-bound FXa (plt-FXa) and thus they compete to form their respective substrate-enzyme complexes before their cleavage to FVa and FVIIIa (Figure 6A). To explore whether this competition helps explain the model results, we quantified how much FVIII and FV are activated by FXa, and how these amounts are changed when plasma levels of FV and prothrombin are altered. FVIII and FV are activated in the model both by FXa and by thrombin, and FVIIIa and FVa are “consumed” in the reactions forming plt-FVIIIa:FIXa and plt-FVa:FXa, respectively. Thus, we cannot measure FXa-mediated activation of FVIII and FV simply by looking at the concentrations of FVIIIa and FVa.

Figure 6. Substrate competition for FXa: a potential mechanism.

(A) Kinetic scheme of substrate competition of FV and FVIII for FXa. [“N” denotes normal (100%),“LN” denotes low-normal (50%), and “HN” denotes high-normal (150%) of the respective baseline plasma level; N-FII = 1400 nM, N-FV = 10 nM.] (B) plt-FVa:FXa, complex on platelet surface; (C) plt-FVIII:FXa, tenase complex on platelet surface; during a time course of 40 min. Description of labels are given in Table 1. All simulations performed at TF = 5 fmol/cm2.

The model provides direct measures of FXa-mediated cofactor activation. Michaelis-Menten kinetics are not appropriate for the complex coagulation reaction system which includes multiple instances of substrates competing for a particular enzyme and of enzymes competing for a particular substrate. Therefore, the model describes reactions using more fundamental mass-action kinetics. Thus, the model equations track all reactants, reaction intermediates, and products. The model expression kVIIIcat[plt-FVIII:FXa] is the rate at which FVIII is activated by FXa on APS. Similarly, kVcat[plt-FV:FXa] is the rate at which FVa is produced by FXa on APS. These formulas show that the rates of FVIII and FV activation by FXa change if the complex concentrations [plt-FVIII:FXa] and [plt-FV:FXa] change. Therefore, to compare FVIII and FV activation by FXa under various conditions, we look at how [plt-FVIII:FXa] and [plt-FV:FXa] change under those conditions. Figure S7 illustrates this concept for a simple system.

Figure 6B–C show how [plt-FV:FXa] and [plt-FVIII:FXa] change in time in the simulations that produced the thrombin curves in Figure 3D, using normal and low-normal levels of FV and normal and high-normal levels of prothrombin. For both complexes, there is a clear separation between the curves with low-normal FV and those with normal FV. Importantly, [plt-FVIII:FXa] is higher for both low-normal FV cases than for the normal FV cases. Further, changing prothrombin levels within each of the FV cases had a minimal effect for the first 25 minutes of the simulation. This means that reducing the plasma FV levels alone caused the increase in the concentration of plt-FVIII:Xa and thus increased activation of FVIII by FXa. Additional simulations show that with 1% normal FVIII, further decrease in FV levels (down to 3%) enhances thrombin generation and further increase in FV levels (up to 200%) inhibits thrombin generation (Figure S2).

In separate simulations, we isolated the competition between FV and FVIII for FXa by adjusting the kinetic rate constants that govern the formation of the substrate-enzyme complexes, while keeping the FV and prothrombin plasma concentrations at their normal levels (Table S3, Figure S8). We found that increasing the rate constant for association of plt-FVIII and plt-FXa by 50% leads to minimal additional thrombin production while increasing this rate and concurrently decreasing the rate constant for association of plt-FV and plt-FXa by 50% leads to a 30-fold higher thrombin concentration at 40 minutes. These results support the notion that, in the model, substrate competition between FV and FVIII for FXa is a mechanism to rescue thrombin generation under FVIII-deficient conditions.

The influence of thrombin and APC on thrombin generation with low-normal FV

Formation of tenase and prothrombinase complexes is regulated by both thrombin activation of FV and FVIII and APC inhibition of FVa and FVIIIa, via positive and negative feedback, respectively. To explore the influence of these feedbacks on thrombin generation when FV is lowered, we performed simulations in which we systematically turned one or both of them off. We then calculated the normalized concentrations of thrombin, generated after 5 and 40 minutes (initiation and propagation phases), and compared them across two cases: one with normal FII, normal FV and one with normal FII, low-normal FV (Figures S9A–B). We found that thrombin generation rescue by low normal FV is minimally affected by changes in the APC feedback. Thrombin-mediated activation of FV and FVIII, to reinforce the heightened activation of FV and FVIII by FXa earlier in the process, was necessary to produce a significant and sustained thrombin response whether or not APC-mediated inhibition is present.

Discussion

Motivated by the variability in bleeding among individuals with similar FVIII levels, we hypothesized that when FVIII is low, variations in other plasma protein levels within the normal range could modify thrombin generation. To test this hypothesis, we used a mechanistic mathematical model to suggest potential modifiers of thrombin generation under flow and FVIII deficiency. Using the mathematical model with a specified, critical TF level and 1% FVIII, we varied all other plasma protein levels to obtain model outputs on which we could apply a GSA. The GSA identified that a reduction in FV from a normal to low-normal level could push the coagulation system to generate more thrombin. When the low-normal level of FV was combined with a high-normal level of prothrombin, thrombin generation in the model was further enhanced. These observations were then verified in a microfluidic model of thrombus formation and CAT. Since the mathematical model was not constructed to model these experimental models, exact quantitative agreement is not expected. Further exploration with the model suggested a potential mechanism: a reduction in FV lessens the substrate competition between plt-FV and plt-FVIII for plt-FXa, leading to more activation of plt-FVIII, which leads to more tenase and thus more prothrombinase, and ultimately boosts thrombin generation.

In our simulations, plt-FXa is the dominant activator of FV and FVIII before significant amounts of thrombin have been produced. The assumption that FXa can activate FV on an APS is based on [36] and studies using tick saliva protein [37]. There is in vitro evidence that both thrombin and FXa can activate FVIII bound to an APS [38,39]. FVIII circulates in the plasma bound with von Willebrand factor (vWF) and may be protected from activation by FXa in this bound state [40,41]. However, this protection may be mitigated during clot formation when vWF binds to APS; the FVIII attached to the vWF may redistribute to the APS since FVIII has similar affinities for vWF and phospholipid surfaces [42,43]. Our results suggest that further biochemical studies of FXa and its role in activating FVIII are needed.

FV is contained in and secreted from platelet α-granules, a mechanism that is incorporated into our model [8,10]. Approximately 20% of the FV in blood is contained in platelets [44]. Platelet FV comes from plasma FV that is endocytosed by megakaryocytes [45–47], thus we assume in the model that a percent change in FV plasma levels correlates with an equal percent change in the platelet FV levels. However, the true correlation between the two FV pools is unknown. Platelet FV is distinct from plasma FV due to modifications in megakaryocytes [48] and some fraction of this pool may be more procoagulant than plasma FV [45,49]. In our model both platelet-derived and plasma FV pools have the same biochemical characteristics. A related limitation is that the mathematical model currently does not account for TFPIα blocking the assembly and activity of prothrombinase by binding to procoagulant, platelet-derived FV or to FXa-activated FV [50,51]. Recent studies showed that TFPIα and FV were negative determinants of thrombin generation using hemophilic plasma [52] and that TFPIα antagonism could enhance fibrin deposition in hemophilia blood under flow [53]. Thus, it will be important to include TFPIα and various forms of FV in future work. Nevertheless, the current version of our model suggests that low-normal FV would enhance thrombin generation under flow in FVIII deficient blood, and this hypothesis was confirmed with a microfluidic assay.

We are unaware of previous reports demonstrating a relationship between FVIII deficiencies, FV levels within the normal range, and thrombin generation. A mutation in a molecular chaperone that transports proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi results in a combined FV and FVIII deficiency [54]. This mutation causes low levels (5–30%) of both FV and FVIII. Model simulations with combined low FV-levels (below 5% of normal) and FVIII-levels (1% of normal) showed that thrombin was inhibited, which is in agreement with the combined FV and FVIII-deficiencies. This is different than our findings where thrombin generation for FVIII deficiencies is modulated by low-normal FV. There are reports of individuals with both a FVIII deficiency and FV Leiden [55] that have a milder bleeding phenotype [56], but this is distinct from the potential mechanism we propose here. Low FV is associated with an increased risk for venous thrombosis [57], suggesting elevated thrombin generation, however there is no current mechanistic explanation for this association.

A major implication of our findings is that FV levels could be an inherent modifier of bleeding risk in combination with FVIII deficiency in hemophilia A. ETP in thrombin generation assays has been associated with differences in bleeding patterns within clinical phenotypes of hemophilia A [58, 59], and we observed an increase in ETP when inhibiting FV in FVIII deficient plasma. However, studies of clinical bleeding in individuals with hemophilia A with different FV levels are needed to support this hypothesis. Our study also shows how a systems biology approach to coagulation can facilitate discovery of previously unrecognized interactions and may serve as a platform to study other highly complex clinical problems.

Supplementary Material

Essentials.

The sources of variability in bleeding in individuals with similar FVIII deficiencies are unknown.

A mathematical model identified the effect of coagulation protein levels on thrombin generation.

FV levels had the greatest influence on thrombin generation in FVIII-deficient blood.

Low-normal FV enhanced thrombin generation and fibrin formation in FVIII-deficient blood.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (R01HL120728) and National Science Foundation (CBET-1351672).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Blanchette VS, Key NS, Ljung LR, et al. Definitions in hemophilia: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1935–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carcao MD, Berg HM, Ljung R, Mancuso ME, PedNet, Rodin Study Group. Correlation between phenotype and genotype in a large unselected cohort of children with severe hemophilia A Blood. 2013;121:3946–52, S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nogami K, Shima M. Phenotypic heterogeneity of hemostasis in severe hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015; 41:826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Modifiers of clinical phenotype in severe congenital hemophilia. Thromb Res. 2017;156:60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlitt T, Brazma A. Current approaches to gene regulatory network modelling. BMC Bioinformatics.2007;8 Suppl 6:S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janes KA, Yaffe MB. Data-driven modelling of signal-transduction networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberhardt MA, Palsson BØ, Papin JA. Applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuharsky AL, Fogelson AL. Surface-mediated control of blood coagulation: The role of binding site densities and platelet deposition. Biophys J. 2001;80:1050–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogelson AL, Tania N. Coagulation under flow: The influence of flow-mediated transport on the initiation and inhibition of coagulation. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2005;34:91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leiderman K, Chang W, Ovanesov M, Fogelson AL. Synergy between tissue factor and factor XIa in initiating coagulation. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2334–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okorie U, Denney WS, Chatterjee MS, Neeves KB, Diamond SL. Determination of surface tissue factor thresholds that trigger coagulation at venous and arterial shear rates: Amplification of 100 fM circulating tissue factor by flow. Blood. 2008;111:3507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kastrup CJ, Runyon MK, Shen F, Ismagilov RF. Modular chemical mechanism predicts spatiotemporal dynamics of initiation in the complex network of hemostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:15747–15752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kastrup CJ, Shen F, Runyon MK, Ismagilov RF. Characterization of the threshold response of initiation of blood clotting to stimulus patch size. Biophys J. 2007;93:2969–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runyon MK, Johnson-Kerner BL, Kastrup CJ, Van Ha TG, Ismagilov RF. Propagation of blood clotting in the complex biochemical network of hemostasis is described by a simple mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7014–7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen F, Kastrup CJ, Liu Y, Ismagilov RF. Threshold response of initiation of blood coagulation by tissue factor in patterned microfluidic capillaries is controlled by shear rate. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2035–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saltelli A, Tarantola S, Campolongo F, Ratto. Sensitivity analysis in practice: a guide to assessing scientific models. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatterjee MS, Denney WS, Jing H, Diamond SL. Systems Biology of Coagulation Initiation: Kinetics of Thrombin Generation in Resting and Activated Human Blood. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danforth CM, Orfeo T, Mann KG, Brummel-Ziedins KE, Everse SJ. The impact of uncertainty in a blood coagulation model. Math Med Biol. 2009;26:323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luan D, Zai M, Varner JD. Computationally derived points of fragility of a human cascade are consistent with current therapeutic strategies. PLoS Comp Bio. 2007;3:e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danforth CM, Orfeo T, Everse SJ, Mann KG, Brummel-Ziedins KE. Defining the boundaries of normal thrombin generation: investigations into hemostasis. PloS One. 2012;7:e30385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link KG, Stobb MT, Di Paola J, et al. A local and global sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model of coagulation and platelet deposition under flow. PloS One. 2018;13:e0200917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogelson AL, Hussain YH, Leiderman K. Blood clot formation under flow: The importance of factor XI depends strongly on platelet count. Biophys J. 2012;102:10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn ML, Nakanishi-Matsui M, Shapiro MJ, Ishihara H, Coughlin SR. Protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 mediate activation of human platelets by thrombin. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onasoga-Jarvis AA., Leiderman K, Fogelson AL, et al. The effect of factor VIII deficiencies and replacement and bypass therapies on thrombus formation under venous flow conditions in microfluidic and computational models. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodeghiero F, Tosetto A, Abshire T, et al. ISTH/SSC Bleeding Assessment Tool: A Standardized Questionnaire and a Proposal for a New Bleeding Score for Inherited Bleeding Disorders J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2063–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Rapid and efficient incorporation of tissue factor into liposomes. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu S, Travers RJ, Morrissey JH, Diamond SL. FXIa and platelet polyphosphate as therapeutic targets during human blood clotting on collagen/tissue-factor surfaces under flow Blood. 2015;126:1494–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics. 1964;6:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:1087–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleck RA, Rao LVM, Rapaport SI, Varki N. Localization of human tissue factor antigen by immunostaining with monospecific, polyclonal anti-human tissue factor antibody. Thromb Res. 1990;59:421–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolton-Maggs PHB, Pasi KJ. Haemophilias A and B Lancet. 2003;361:1801–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helton JC, Davis FJ. Latin hypercube sampling and the propagation of uncertainty in analyses of complex systems. Reliab Eng Sys Safe. 2003;81:23–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobol IM. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math Comput Simulat. 2001;55:271–280. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemker HC, Giesen P, Al DR, et al. Calibrated Automated Thrombin Generation Measurement in Clotting Plasma. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monkovic DD, Tracy PB. Activation of human factor V by factor Xa and thrombin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuijt TJ, Bakhtiari K, Daffre S, et al. Factor Xa activation of factor V is of paramount importance in initiating the coagulation system: Lessons from a tick salivary protein. Circulation. 2013;128:254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furby FH, Berndt MC, Castaldi PA, Koutts J. Characterization of calcium-dependent binding of endogenous factor VIII/von Willebrand factor to surface activated platelets. Thromb Res. 1984;35:501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuenschwander P, Jesty J. A comparison of phospolipid and platelets in the activation of human Factor VIII by thrombin and Factor Xa, and in the activation of Factor X Blood. 1988;72:1761–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donath MJSH Lenting PJ, van Mourik JA, Mertens K. The role of cleavage of the light chain at positions Arg1669 or Arg1721 in subunit interaction and activation of human blood coagulation. Factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3648–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koedam JA, Hamer RJ, Beeser-Visser NH, Bouma BN, Sixma JJ. The effect of von Willebrand factor on the activation of factor VIII by factor Xa. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saenko EL, Shima M, Sarafanov AG. Role of activation of the coagulation FVIII in interaction with vWf, phospholipid, and functioning within the Factor Xase complex. Trends Cardiovas Med. 1999;9:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spaargaren J, Giesen PLA, Janssen MP, Voorberg J, WIllems GM, van Mourik JA. Binding of blood coagulation Factor VIII and its light chain to phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine bilayers as measured by ellipsometry. Biochem J. 1995;310:539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tracy PB, Eide LL, Bowie EJ, Mann KG. Radioimmunoassay of factor V in human plasma and platelets. Blood. 1982;60:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camire RM, Pollak ES, Kaushansky K, Tracy PB. Secretable human platelet-derived factor V originates from the plasma pool. Blood. 1998;92:3035–3041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouchard BA, Williams JL, Meisler NT, Long MW, Tracy PB. Endocytosis of plasma-derived factor V by megakaryocytes occurs via a clathrin-dependent, specific membrane binding event. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gould WR, Simioni P, Silveira JR, Tormene D, Kalafatis M, Tracy PB. Megakaryocytes endocytose and subsequently modify human factor V in vivo to form the entire pool of a unique platelet-derived cofactor. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayombil F, Abdalla S, Tracy PB, Bouchard BA. Proteolysis of plasma-derived factor V following its endocytosis by megakaryocytes forms the platelet-derived factor V/Va pool. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1532–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monkovic DD, Tracy PB. Functional Characterization of Human Platelet-released Factor V and its Activation by Factor Xa and Thrombin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17132–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood JP, Bunce MW, Maroney SA, Tracy PB, Camire RM, Mast AE. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-alpha inhibits prothrombinase during the initiation of blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:17838–17843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood JP, Petersen HH, Yu B, Wu X, Hilden I, Mast AE. TFPIα interacts with FVa and FXa to inhibit prothrombinase during the initiation of coagulation. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2692–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chelle P, Montmartin A, Damien P, et al. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor is the main determinant of thrombin generation in haemophilic patients. Haemophilia. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomassen S, Mastenbroek TG, Swieringa F, et al. Suppressive Role of Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor-α in Platelet-Dependent Fibrin Formation under Flow Is Restricted to Low Procoagulant Strength. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:502–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nichols WC, Seligsohn U, Zivelin A, et al. Mutations in the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment protein ERGIC-53 cause combined deficiency of coagulation factors V and VIII. Cell. 1998;93:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nichols WC, Amano K, Cacheris PM, et al. Moderation of hemophilia A phenotype by the factor V R506Q mutation. Blood. 1996;88:1183–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee DH, Walker IR, Teitel J, et al. Effect of the factor V Leiden mutation on the clinical expression of severe hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rietveld IM, Bos MHA, Lijfering WM, et al. Factor V levels and risk of venous thrombosis: The MEGA case-control study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2018;2:320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dargaud Y, Béguin S, Lienhart A et al. , Evaluation of thrombin generating capacity in plasma from patients with haemophilia A and B. Thromb Haemost 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tarandovskiy ID, Balandina AN, Kopylov KG et al. , Investigation of the phenotype heterogeneity in severe hemophilia A using thromboelastography, thrombin generation, and thrombodynamics. Thromb Res 2013;131(6):e274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.