Abstract

Objectives:

Experiencing an immigration-related arrest of a family member adversely impacts youth well-being, yet the role of parental documentation status for exacerbating adverse mentalhealth outcomes following these arrests has not been investigated.

Methods:

Using a general population sample of Latino 7th grade students in an urban public-school district in the South-Central U.S. (N = 611), we examined the relationship between an immigration-related arrest of a family member and depressive symptoms as well as the moderating associations of perceived parental documentation status.

Results:

Using ordinary least squares regression, findings indicate that experiencing or witnessing an immigration-related arrest of a family member is significantly associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms. Moreover, parental citizenship status has a moderating effect; depressive symptoms are magnified among youth who report that both of their parents have undocumented legal status.

Conclusions:

The study findings suggest that there are significant consequences for youth well-being when a family member is arrested for immigration-related violations. Further, among youth whose parents are both undocumented, there appears to be a compounding effect on mental health. Immigration policies, programs, and schools need to consider the emotional needs of youth who have undocumented parents, particularly in the context of elevated immigration enforcement.

Keywords: Immigration, Undocumented, Latino, Adolescence, Depression

More than 4.6 million undocumented immigrants (foreign-born individuals residing in the U.S. without the proper authorization) were apprehended by immigration officials from the U.S. between 2000 and 2014; a number that is nearly double the total number of individuals deported in the history of the U.S. prior to 2000 (Office of Immigration Statistics, 2014). Having family members removed from the home due to immigration enforcement—or merely fearing detention or deportation—is linked to adverse outcomes for children such as stress, poor physical and emotional health, and depression (Capps et al., 2015; Robjant, Hassan, & Katona, 2009). The effects of having family members detained or deported, however, are not only limited to those children who are themselves at risk of detention or deportation. Approximately 5.3 million children live with undocumented parents, 85% of whom are U.S.-born citizens (Passel, Cohn, Krogstad, & Gonzalez-Barrera, 2014). For these children, there is a persistent threat of arrest, detention, and possibly deportation of their parents (Rojas-Flores et al., 2017). Children who are U.S. citizens are therefore vulnerable to separation from their parents due to immigration enforcement, whereas children who have undocumented status are vulnerable to immigration-related arrests, detention, and deportation themselves. In this study, we utilize a population-based sample of Latino early adolescent youth in a new arrival state to examine how experiencing or witnessing the immigration-related arrest of a family member is associated with depressive symptoms. Further, we examine the moderating effect of perceived parental documentation status for youth depressive symptoms.

Family Stress and Early Adolescence

Although previous studies have chronicled the consequences of immigration-related arrests, detention, and the deportation of family members on children’s well-being, there are some gaps in the literature. In particular, there is a dearth of population-based data as well as a limited focus on adolescents as compared to younger children. Social, cognitive, and physical changes that occur during the transition from childhood to adolescence are associated with different vulnerabilities for early adolescents as compared to younger children (Kroger, 2007). In particular, early adolescence is a key developmental period where youth may become more aware of, and thus more vulnerable to, family stressors (Kiang, Andrews, Stein, Supple, & Gonzalez, 2013). This may cause adolescents to detrimentally manifest family stress, such as having increased depression, engaging in substance use, or other externalizing behavioral conduct problems (Hammack, Robinson, Crawford, & Li, 2004; Telzer, Gonzales, & Fuligni, 2014; White, Liu, Nair, & Tein, 2015). Although prior research has not examined the impact of immigration-related arrests/detention for early adolescent well-being per se, insights from research on early adolescents who are exposed to an arrest of a family member are informative for the current study. Roberts and colleagues (2014) found that among a sample which included early adolescents, arrest exposure was statistically associated with greater behavioral and emotional challenges beyond the control variables of age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, caregiver’s education, and parenting factors. They posited that because coping skills are still developing in late childhood and early adolescence, the deleterious outcomes following arrests of family members may be magnified.

Implications of Immigration-Related Arrests

Immigration policies and practices leading to family member detainment or deportation mark a potentially permanent change in the configuration of a family (Dreby, 2012). Many children with immigrant parents in the U.S. live in poverty, suffer discrimination, experience their parents’ stress and anxiety, and have poor physical and mental health (Gulbas et al., 2016). Experiencing the arrest of a family member due to immigration reasons can further compound the detrimental effects of these pre-existing stressors for the child’s mental health (Zayas & Cook Heffron, 2015). In a comprehensive review of the literature from 2009–2013, Capps and colleagues (2015) found that children experience psychological trauma, material hardship, residential instability, academic withdrawal, and family dissolution after the detention of a family member. For example, children whose parents were detained or deported exhibit increased crying, eating and sleeping disturbances, clingy behavior, increased fear and anxiety, anger and aggression, and generalized fear of law enforcement (Cervantes, Ullrich, & Matthews, 2018; Chaudry et al., 2010; Dreby, 2012). After immigration raids in the home, children report feeling abandoned, isolated, fearful, traumatized, and depressed (Capps, 2007). Consequences are more profound when children witness their parents being arrested (Chaudry et al., 2010). Moreover, the arrest of close family members has been linked to long-term emotional and behavioral issues, including substance abuse, unemployment and interpersonal problems (Gulbas et al., 2016).

Undocumented Parents and Fear of Immigration-Related Arrests

Having undocumented parents can cause adverse consequences for children in the U.S. (regardless of their own citizenship status) due to increased family stress, fear of family members being taken, poor employment conditions and reduced income and unsafe housing (Capps, 2016). Dreby (2012) found that while the majority of children in her study had not had a parent detained or deported by immigration, the threat of deportability and immigration raids affected them profoundly. According to Gulbas and colleagues (2016), perhaps the greatest stressor for a U.S.-born child of undocumented parents is fear of the discovery of their parents by U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials. The threat of a parent or other family member’s detention by ICE due to documentation status causes children to have constant anxiety and hyper-vigilance about family member’s safety (Gulbas et al., 2016). The rules that often govern families with undocumented parents are “be silent about your family, tell no one about us” and “be still, don’t draw attention by anything you do” (Zayas & Cook Heffron, 2015, p. 1). Concomitantly, research generally shows that children whose parents live in an acute state of deportability due to documentation concerns experience high levels of stress and anxiety (Dreby, 2012; Gulbas et al., 2016). Among children of Latino immigrants, stress levels are highest for those most vulnerable to having a parent apprehended by immigration (Brabeck & Xu, 2010).

Less attention in research has been given to mixed-status parents (that is, families where one parent is documented and the other is not) and consequences for adolescent adjustment, as studies more commonly feature families having both parents classified as undocumented (Delva et al., 2013). In an exception, Ortega and colleagues (2009) compared family documentation status differences among Latino families of Mexican origin (both parents documented, at least one parents documented, and neither parent documented) and found that children in families where one or both parents identified themselves as undocumented had greater odds of developmental risks (e.g., behavioral or developmental problems, such as decreased cognition) compared with families where both parents held legal documentation status. Although their study investigated each parent’s documentation status individually and found that both undocumented groups (one or both parents undocumented) had similar outcomes, it is unclear whether the pattern would be the same in the case of immigration enforcement; the risks associated with having one parent removed from the home—albeit a traumatic experience—may not be great as having both parents removed.

Situational Context

Demographic variables for gender, economic hardship, and age were included as controls due to previously identified linkages with adolescent mental health. Adolescent females, for example, are about twice as likely as males to report depressive symptoms (Wade, Cairney, & Pevalin, 2002). Economic hardship is associated with poor mental health, particularly with immigrant families (Alegría, Green, McLaughlin, & Loder, 2015). Additionally, prior research has found that mental health (including psychological distress) in adolescence is associated with pubertal hormones (Sisk & Zehr, 2005). Because our sample straddles the line between pre-pubescent and post-pubescent age groups, age was added as a variable to control for any potential confounding due to puberty.

Current Study

The current study extends the literature on the implications of an immigration-related arrest of a family member, perceived parental documentation status, and adolescent well-being in several ways. Using a general population sample of 7th grade Latino students in an urban school district in the South-Central U.S., we first explore the prevalence of the experience of the immigration-related arrest of a family member and compare self-reported depressive symptoms between youth who have and have not experienced this event. Further, we examine the relationships between experiencing an immigration-related arrest of a family member, parental documentation status, and depressive symptoms. Finally, we examine the interaction between an immigration-related arrest of a family member and parental documentation status to determine if depressive symptoms are highest among youth with both circumstances. It is expected that among Latino youth who experienced or witnessed an immigration-related arrest of a family member, having at least one parent with an undocumented status should serve as an additional risk factor for psychological distress. Because having two parents removed from the home would likely result in a change in guardianship and residence, we expect psychological distress to be greatest when both parents are undocumented. Therefore, we hypothesize that parental documentation status will moderate the link between an immigration-related arrest of a family member and depressive symptoms. We further expect that depressive symptoms will be highest among youth who both experienced an immigration-related arrest of a family member and report both parents to have undocumented status.

Method

Sample

The sample draws from a larger data set of 7th grade students enrolled in an urban school district in a state in the South-Central U.S. (N = 1,736). The sample for the current study was restricted to the 661 Latino youth, of which 50 had missing data, resulting in a sample size of 611 youth participating in the study, 180 (29%) of whom experienced an immigration-related arrest of a family member.

Procedures

The home institution’s Office of Research Compliance and Institutional Review Board, the school district’s Research and Evaluation Department, and the principal of each school examined the study procedures and granted authorization to conduct the study, which included the approved parent consent and adolescent assent forms. Parental consent forms were sent home to parents for review and copies of surveys were made available at both libraries and school offices (as well as an online option for parents to view). Because the study procedure was anonymous, a passive parental consent process was utilized, which required parents to return the consent form only if they wished to opt their child out of participating. All students were surveyed if: (1) their parents did not object to their involvement in the study, (2) they attended school the day of data collection, and (3) they gave assent to participate, resulting in a participation rate of 98% of students at school the day of data collection (a total response rate of 83% of all potential 7th grade student participants). Data were gathered using a standardized self-report questionnaire. Students were given the option to take the survey in English or Spanish; however, only 39 students (5.9%) opted for the Spanish version. The survey was translated into Spanish by a bilingual member of the research team, back translated to English by another bilingual research team member, and then the two worked together to resolve any discrepancies. Finally, we piloted the survey with a group of Latino students for its face validity before launching data collection. Students with learning disabilities severe enough to be exempt from year-end exams were excluded from the study. Students were verbally debriefed following completion of the survey and received $5 each for participating.

Measures

Depressive Symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were measured using a 10-item set of questions derived from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies — Depression Scale (CES-D; Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). The 10-item version of the CES-D has validity and reliability that is acceptable among adolescents and has been utilized with various community samples (see Bradley, Bagnell, & Brannen, 2010 and Cheung, Liu, & Yip, 2007 for examples). Participants were asked to identify how often they agreed with the statements in the past two weeks, including items such as: “My sleep was restless;” “I felt depressed;” and “I felt that everything I did took effort.” Responses were coded on a 4-point Likert scale with answers ranging from “0” (never/rarely) to “3” (most/all the time). Items were coded and recoded so that higher scores were indicative of more depressive symptoms. The scale items were summed to create a scale ranging from 0–30. Alpha reliability for the scale using this sample was α =.76.

Immigration-Related Arrests

The arrest of a family member for immigration reasons was assessed by the question, “Have you ever known of or seen a family member taken away by immigration officials?” Answers were coded as “0” for no and “1” for yes.

Perceived Parental Documentation Status

Youth were asked about their parental documentation status with the question, “What is your parents’ citizenship status in the U.S.?” with response options including “Both are U.S. citizens or legal residents,” “One is not a legal resident,” and “Both are not legal residents.” The original variable was then coded into three dummy variables (e.g., dichotomous variables coded as 0 or 1) representing one undocumented parent, two undocumented parents, and the reference variable indicating both parents are U.S. citizens/legal residents.

Demographic and Control Variables.

Female was coded as “1”, with “0” indicating male. Economic hardship was measured using three modified line-item questions derived from the 1990 survey of Work, Family, and Well-Being (WFW; Ross & Wu, 1995) and the 1995 Survey of Aging, Status, and Sense of Control (ASOC; Mirowsky & Ross, 2005). Questions included: “In the past year...Did you receive welfare or assistance from church or community organizations?” “Did your family go without meals?” and “Did you live outdoors, in a shelter, or a transitional housing facility?” Responses included “Yes” and “No.” Items were then summed to construct a scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more economic hardship experiences. Age was assessed by the question, “How old are you?” with response options ranging from 12–16

Analytic Strategy

Linear regression models were used to investigate the relationship between having a family member arrested for an immigration violation, documentation status, and depressive symptoms. Because of low levels of missing values (percentages missing range from 0.9 to 2.8) and because no systematic patterns were detected utilizing Bonferroni corrections, missing values were categorized as missing completely at random and treated using listwise deletion. Listwise deletion of missing data is regarded as an unbiased way of handling data when missing completely at random is a legitimate assumption (Allison, 2002). It is worthy to note that listwise deletion results in 50 cases excluded in the analyses. Mean difference tests were conducted on those 50 cases and the remaining 611 cases among all study variables. No significant group differences were found.

Table 1 presents mean differences by family member arrest status for the study variables using t-tests and chi-square tests. We then conducted a series of linear regression models in order to assess the association between the study variables and adolescents’ reports of depressive symptoms (see Table 2). Model 1 included only the immigration-related arrest variable. Model 2 included the parental documentation variables. Model 3 included the control variables of gender, economic hardship and age. Model 4 added the interaction moderators of parental documentation status, which was calculated by the product of the immigration-related arrest variable and each parental documentation status variable (one parent undocumented and both parents undocumented, with both parents documented as the reference category), respectively.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables by Immigration-Related Arrest (N=611).

| Variables | Sample | No Arrest (N=431) | Immigration-Related Arrest (N= 180) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M or% | SD | M or% | SD | M or% | SD |

t-test/χ2 statistic |

p | |

| Depressive symptoms | 9.15 | 5.22 | 8.42 | 4.82 | 10.87 | 5.73 | −5.196a | *** |

| Immigration-related arrest | 29% | |||||||

| Parental citizenship status | ||||||||

| Both US citizens/legal resident | 49% | 54% | 36% | 17.552b | *** | |||

| One parent US citizen/legal resident | 20% | 18% | 27% | 6.906b | ** | |||

| Neither parent US citizen/legal resident | 31% | 28% | 37% | 5.023b | * | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Female | 46% | 45% | 49% | .608b | ||||

| Economic hardship | .22 | .50 | .21 | .50 | .26 | .49 | −.924a | |

| Age | 13.14 | .66 | 13.09 | .65 | 13.24 | .67 | −2.220a | * |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

= t-test statistic,

= Chi-square test statistic.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression of Psychological Distress by Immigration-Related Arrest, Parental Citizenship Status, and Demographics among Early Adolescent Latinos (N=611).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |||||

| Immigration-related arrest | 2.44 | *** | .45 | 2.35 | *** | .46 | 2.14 | *** | .46 | .85 | .71 | |

| Parental citizenship status1 | ||||||||||||

| One parent US citizen/legal resident | .48 | .55 | .26 | .54 | −.18 | .66 | ||||||

| Neither parent US citizen/legal resident | .50 | .48 | .36 | .48 | −.35 | .56 | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1.49 | *** | .41 | 1.46 | *** | .41 | ||||||

| Economic hardship | .69 | .41 | .66 | .41 | ||||||||

| Age | .99 | ** | .31 | .99 | ** | .31 | ||||||

| Interactions2 | ||||||||||||

| Immigration-related arrest * One parent US citizen/legal resident | 1.71 | 1.16 | ||||||||||

| Immigration-related arrest * Neither parent US citizen/legal resident | 2.52 | * | 1.05 | |||||||||

| Intercept | 8.43 | *** | .25 | 8.20 | *** | .31 | −5.55 | 4.14 | −5.21 | 4.13 | ||

Reference group: Both parents US citizens/legal residents.

Reference group: Family member deported*Both parents US citizens/legal residents

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for study variables for the full sample and separately for adolescents who experienced an arrest of a family member for immigration violations and those who had not. Almost one-third (29%) of adolescents reported an arrest of a family member for an immigration violation. The average depressive symptom score among all adolescents in the sample was 9.15, and youth who reported arrest of a family member for immigration violations reported significantly higher depressive symptoms (M = 10.87 vs. M = 8.42; p < .001) than youth who did not. Applying the conservative cut-off of 10 indicating depression (Andresen et al., 1994) suggests that youth who experienced an immigration-related arrest of a family member are at risk for clinical depression. A total of 20% of participants identified as having one undocumented parent, 31% identified both parents as undocumented, and the remaining 49% reported that both parents were citizens/legal residents. Youth who reported an immigration-related arrest of a family member also reported a significantly higher proportions of only one (M = 27%; p < .01) or neither parent (37%; p < .05) as having legal status in the U.S., compared to youth who did not experience an arrest of a family member. Among participants in the sample, 46% reported being female, the mean age was 13.14 years, and the mean economic hardship score was .22 (ranging from 0 to 3).

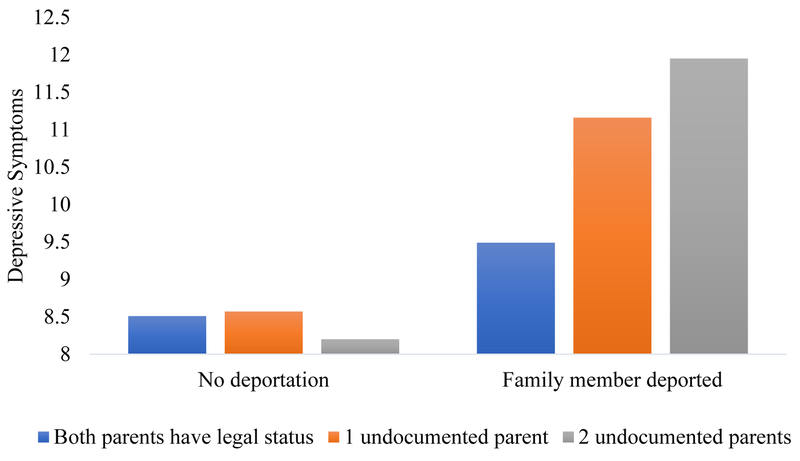

Table 2 presents results of linear regression models conducted to investigate the associations between an immigration-related arrest of a family member, parental documentation status, and youth depressive symptoms. Results of Model 1 indicate that experiencing the arrest of a family member for immigration violations was associated with significantly higher depressive symptoms (B = 2.44, p < .001). Model 2 included the parental documentation variables. Parental documentation status was not associated with youth depressive symptoms. In other words, neither undocumented parent combination (one or both parents being undocumented) was significantly different than having both parents as legal residents/U.S. citizens in terms of their associations with depressive symptoms. Model 3 added the control variables of female, economic hardship, and age. Both the female (B = 1.49, p < .001) and age (B = .99, p < .01) variables were statistically significant in predicting depressive symptoms, with being female and older associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Lastly, Model 4 added the variables indicating an interaction between an immigration-related arrest of a family member and parental documentation status. With the interaction included in the model, the interpretation of main effects differs. Depressive symptoms are not higher among youth who report an immigration-related arrest of a family member when both parents are U.S. citizens or legal residents. Depressive symptoms also are not significantly higher among youth who report one or both parents have undocumented legal status when they have not experienced the immigration-related arrest of a family member. Yet results indicate that when youth experience the immigration-related arrest of a family member, depressive symptoms are significantly higher among those with two undocumented parents. Figure 1 presents the interaction finding visually, which highlights that Latino youth who did not experience the immigration-related arrest of a family member reported depressive symptoms below the clinical cut-off for depression. Reported depressive symptoms were higher among those who experienced the immigration-related arrest of a family member, particularly among those with two undocumented parents.

Figure 1.

Immigration-Related Arrests and Youth Depressive Symptoms by Parental Documentation Status: Regression Interaction Results

Discussion

We examined the associations between youth reported the arrest of a family member for immigration-related reasons, parental documentation status, and depressive symptoms in an urban sample of Latino 7th grade students. While other studies have examined depression or depressive symptomology among children following a family member being detained by immigration (Allen, Cisneros, & Tellez, 2015; Brabeck, Lykes, & Hershberg, 2011; Dreby, 2012; Horner et al., 2014), none utilized a large population-based sample of adolescents (the largest to our knowledge examines 110 children, with only 20% of those children experiencing a family member being taken by immigration; Dreby, 2012). To date, our sample comprises the largest number of participating youth who reported experiencing the arrest of a family member for immigration-related violations (a total sample of 611 early adolescents, with 180 experiencing immigration-related arrest of a family member).

Results indicate that Latino youth who experienced an immigration-related arrest of a family member reported significantly higher depressive symptoms than youth who did not. Moreover, the average depression score for youth who experienced the arrest of a family member for immigration violations is above a conservative cut-off score (M = 10) indicating clinical levels of depression (Andresen et al., 1994). Although our measure is not specific to having a parent being arrested (our measure operationalized this as any family member), our findings mirror the results of a growing body of literature on psychological outcomes of immigration-related arrests, detention, and deportation for children such as depression, anxiety, social isolation, self-stigma, aggression, withdrawal and negative academic consequences, and substance abuse (Allen, Cisneros, & Tellez, 2013; Brabeck & Xu, 2010; Capps, 2007; Cervantes et al., 2018; Chavez et al., 2012; Chaudry et al., 2010; Delva et al., 2013; Dreby, 2012; Gonzales, Suárez-Orozco, & Dedios-Sanguineti, 2013; Zayas, 2015; Zayas & Gulbas, 2016).

Because demographic projections highlight that 88% of U.S. population growth over the next five decades will be due to immigrants and their descendants, of which the vast majority will be Latino (Pew Research Center, 2015), adversity experienced by immigrants during childhood has enormous implications for the future health of our nation. Beyond the immediate negative effects for children, a major finding of the past 20 years is the relationship between early life trauma or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and the onset of disease in adolescence and adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998). Moreover, growing evidence suggests that psychological trauma may impact health and life opportunities in a way that reverberates across generations (Garner et al., 2012; Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009; Metzler, Merrick, Klevens, Ports, & Ford, 2017).

Interestingly, our second finding suggests that parental documentation status is not associated with youth depressive symptoms. However, mean levels of depressive symptoms in this sample are quite high. Despite their parents not being in danger of being detained because of immigration reasons (i.e., both legal status), the youth in this sample report depressive symptoms close to the cutoff of 10, suggesting clinical depression. Therefore, rather than regarding citizenship status as unimportant, a more likely interpretation of our null finding is a sort of “spillover effect” such that a general feeling of psychological distress exists in the Latino community due to the stigma attached to being an immigrant or being from an immigrant family. Generalized psychological distress among Latinos of Mexican descent irrespective of documentation status has been found by others (Menjivar & Abrego, 2009; Szkupinski Quiroga, Medina, & Glick, 2014).

This generalized psychological distress is not unfounded. In 1975, United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that having a “Mexican appearance” “constituted a legitimate consideration under the Fourth Amendment for making an immigration stop” (Johnson, 2000, p. 676), a decision still being cited by U.S. courts when adjudicating cases involving immigration enforcement (Briggs, 2015). This has resulted in legalizing micro-aggressions (e.g., commenting on someone’s accent) and macro-aggressions (e.g., use of a blatant racist term) in law enforcement agents casting generalized suspicion over an entire group of people simply because of their supposed Mexican appearance (Briggs, 2015; Romero 2006). One report estimated that 93% of individuals arrested in immigration enforcement are Latino, even though they only comprise 77% of the undocumented population in the U.S. (Kohli, Markowitz, & Chavez, 2011).

Negative portrayals of Latino immigrants by politicians and the media accompanied by aggressive law enforcement that includes racial profiling have exacerbated prejudicial attitudes and anti-immigrant sentiment to a point that there is a heightened level of fear and psychological distress across the profiled group regardless of actual residency status or place of birth (Szkupinski Quiroga, et al., 2014). For example, Dreby (2012) reported that in two very different local contexts (i.e., urban and rural), the daily lives of children of Mexican descent were negatively impacted through state and federal immigration policies that criminalized their parents, relatives, and neighbors regardless of citizenship status and actual involvement with immigration enforcement. These children had begun to conflate being an immigrant with being a criminal, and were stigmatized to the point of actively concealing their immigrant heritage.

Our third finding highlights the additional psychological distress that Latino youth experience when they perceive both of their parents as undocumented and when these youth experience a family member arrested for immigration reasons. As shown in Figure 1, there is little difference in depression scores among youth who had not experienced the immigration-related arrest of a family member, regardless of parental documentation status. Among those who experienced an arrest, however, self-reported depression is highest for youth both parents undocumented when compared to youth for whom both parents have legal status. It may be the case that having undocumented parents creates a level of uncertainty and helplessness about the future that manifests in depressive symptoms, which are magnified if the child has previously experienced an arrest of a family member for immigration reasons. This aligns well with helplessness models of depression (Seligman, 1975) that emphasize uncertain and uncontrollable stressful events as a precipitating and maintaining factor in depression (Alloy, Kelly, Mineka, & Clements, 1990). This interpretation of our findings is further bolstered by others who have found that nearly 75% of Latino youth from immigrant families report living in persistent fear of either being taken by immigration, the fear of others they know being taken, or having someone they know being taken by immigration (Yoshikawa, Suárez-Orozco, & Gonzales, 2017). Latino youth for whom one or both parents are undocumented and have direct knowledge of a family member who has been taken by immigration may live under the constant fear of their family being separated (Arbona et al., 2010), an unambiguous negative event which they cannot predict, nor over which they have any control, and which leads to increased depressive symptoms.

It is important to note that much of the extant research on Latino families and immigration issues to date investigated outcomes associated with adults (e.g., Torres et al., 2018) or children (e.g., Capps et al., 2015), leaving adolescents understudied in the literature. Our study fills some of that gap. In particular, understanding how immigration policies are associated with adolescent mental health is critical. The prevalence of depressive symptoms increases significantly across adolescents (Mojtabai, Olfson, & Han, 2016 ), and high levels of depression in adolescence are associated with a host of adverse risks including school dropout, internalizing and externalizing antisocial behaviors, and suicide risk (Reynolds & Johnston, 2013). Although we cannot solely attribute the gradient of adolescent depressive symptoms to their parents’ documentation status and experiences with immigration, previous investigations on Latino families have found that adolescents are well aware of the immigration challenges both they and their families face, and as a result, may be more vulnerable to family stressors associated with immigration issues (Gurrola, Ayón, & Moya Salas, 2016). Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that family stress during adolescence is associated with longitudinal detrimental outcomes as adults (Walper, 2009). Although younger children are certainly not immune to the effects of immigration, adolescents may feel supplementary pressure to adopt additional family responsibilities as a result, such as assuming the role of interpreter or working to earn money for the family; both of which may compete with other socio-cognitive tasks such as schooling and peer involvement (Jurkovic, 2004).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that immigration policy that results in the arrest and detention of family members is negatively associated with the mental health of Latino adolescents. This is particularly true among youth whose parents both lack legal documentation status in the U.S. Our results converge with a small but growing number of studies suggesting that the impact of immigration policy is not limited to those individuals who are not authorized to reside in the U.S., but extends to create a general sense of psychological distress among much of the Latino community including children and adolescents who are U.S. citizens. When children are continuously concerned and anxious about the stability of their families, it can have long-term and severe negative consequences for their mental health (Brown, 2010; Garner et al., 2012). These findings have implications for school officials, medical practitioners, and others who interact with Latino youth. For example, similar to negative consequences of other types of adverse childhood experiences (Garner et al., 2012; Lupien et al., 2009), it may be that a significant proportion of behavior problems at school can be traced back to the trauma of having a family member arrested for immigration reasons, living under the constant threat of family separation, or simply bearing the burden of the stigma associated with being from an immigrant family. This suggests the potential utility of considering these immigration-related experiences and fears as traumatic events and screening Latino youth before applying punitive actions such as detentions and suspensions. There is an urgent need for educators and others engaging with immigrant youth to be aware of the chronic stress and trauma that these youth frequently experience and how this can affect their emotional development and well-being.

Limitations

Several limitations to the study should be noted. First, data were collected from youth in a single urban South-Central school district and should not be generalized to all Latinos. Because a majority of Latinos in the U.S. reside in areas including California, Florida, and Texas (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017), the findings might vary due to factors such as access to resources, state immigration policies and/or procedures, and social networks. The state where data collection occurred had stricter immigration policies in place during the several years preceding data collection that resulted in a large-scale deportation effort.

Second, there are several study limitations due to survey measures, but all are likely to yield conservative results. For example, although the CED-10 is a widely used short-form measure of depression, it may not adequately capture culturally-nuanced aspects of depressive symptoms more indicative of Latino immigrant youth (Crockett, Randall, Shen, Russell, & Driscoll, 2005). Additionally, the parental documentation status variable was based on youth report as opposed to parent reported documentation status. Although other studies have shown that adolescents are typically aware of their family’s immigration status (Dreby, 2012), parent reports of their own documentation status would likely be more accurate. However, because we are interested in the implications of parental documentation status for their children’s mental health, we argue that even if youth are incorrect in their assessments of their parents’ documentation status, these perceptions play a significant role in youth well-being. Finally, there are limitations to the primary independent variable: the immigration-related arrest of a family member. From the question wording, we cannot ascertain which family member was arrested, nor can we tease out youth who were merely aware about the immigration-related arrest from youth who witnessed the arrest. Additionally, we cannot ascertain what resulted from the arrest; were the family members released shortly, detained or imprisoned, or deported? Moreover, due to survey wording, the variable of interest likely includes both extended family members as well as parents. Yet these limitations due to survey wording are likely to result in conservative estimates for youth depressive symptoms. For example, youth who witnessed the arrest of their parents who were then deported and remain absent from the home would be expected to have more substantial implications for mental health. Yet our sample also would include youth who may merely be aware of an arrest of a family member such as a cousin as well as those whose family members were arrested erroneously and quickly released.

Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes inferring causality. Although it does not seem probable that youth depressive symptoms cause a family member to be arrested due to immigration enforcement, it is possible that unmeasured external factors are responsible for both. Still, this study is among the first to study the association between the immigration-related arrest of a family member, parental documentation status, and Latino early adolescent depressive symptoms in a large population-based sample residing in a non-traditional settlement area for Latinos.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the College of Human Sciences at Oklahoma State University and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM109097; Jennifer Hays-Grudo, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Zachary Giano, Oklahoma State University

Machele Anderson, Oklahoma State University

Karina M. Shreffler, Oklahoma State University

Ronald B. Cox, Jr., Oklahoma State University

Michael J. Merten, Oklahoma State University

Kami L. Gallus, Oklahoma State University

References

- Alegría M, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, & Loder S (2015). Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the US. New York, NY: William T. Grant Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Allison P (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Allen B, Cisneros EM, & Tellez A (2015). The children left behind: The impact of parental deportation on mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Kelly KA, Mineka S, & Clements CM (1990). Comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders: A helplessness-hopelessness perspective In Maser JD & Cloninger CR (Eds.), Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders (pp. 499–543). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, & Wiesner M (2010). Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(3), 362–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck KM, Lykes MB, & Hershberg R (2011). Framing immigration to and deportation from the United States: Guatemalan and Salvadoran families make meaning of their experiences. Community, Work & Family, 14(3), 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck K, & Xu Q (2010). The impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children and families: A quantitative exploration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(3), 341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, & Brannen CL (2010). Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10 in adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 408–412. doi: 10.3109/01612840903484105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs C (2015). The reasonableness of a race-based suspicion: The Fourth Amendment and the costs and benefits of racial profiling in immigration enforcement. Southern California Law Review, 88, 379–412. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL (2010). Marriage and child well-being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1059–1077.doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00750.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R (2007). Paying the price: The impact of immigration raids on America’s children.Washington, DC: The Urban Institute [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Fix M, & Zong J (2016). A profile of US children with unauthorized immigrant parents. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Koball H, Campetella A, Perreira K, Hooker S, & Pedroza JM (2015). Implications of immigration enforcement activities for the well-being of children in immigrant families: A review of the literature Research Report, Sept. 2015. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes W, Ullrich R, & Matthews H (2018). Our children’s fear: Immigration policy’s effects on young children. Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP). [Google Scholar]

- Chaudry A, Capps R, Pedroza JM, Castaneda RM, Santos R, & Scott M (2010). Facing our future: Children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez JM, Lopez A, Englebrecht CM, & Viramontez Anguiano RP (2012). Sufren Los Niños: Exploring the impact of unauthorized immigration status on children’s well-being. Family Court Review, 50(4), 638–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YB, Liu KY, & Yip PSF (2007). Performance of the CES-D and its short forms in screening suicidality and hopelessness in the community. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 79–88. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen Y, Russell ST, & Driscoll AK, (2005). Measurement equivalence of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: A national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Horner P, Sanders L, Martinez R, Lopez WD, & Doering-White J (2013). Mental health problems of children of undocumented parents in the United States: A hidden crisis. Journal of Community Positive Practices, 13, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J (2012). The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 829–845. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, … &Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care. (2012). Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics, 129(1), e224–e231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RG, Suárez-Orozco C, & Dedios-Sanguineti MC (2013). No place to belong contextualizing concepts of mental health among undocumented immigrant youth in the United States. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1174–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas LE, Zayas LH, Yoon H, Szlyk H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, & Natera G (2016). Deportation experiences and depression among US citizen children with undocumented Mexican parents. Child: care, Health and Development, 42(2), 220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Robinson WL, Crawford I, & Li ST (2004). Poverty and depressed mood among urban African-American adolescents: A family stress perspective. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(3), 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Horner P, Sanders L, Martinez R, Doering-White J, Lopez W, & Delva J (2014). “I put a mask on” The human side of deportation effects on Latino youth. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, 2(2), 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Kuperminc G, Perilla J, Murphy A, Ibañez G, & Casey S (2004). Ecological and ethical perspectives on filial responsibility: Implications for primary prevention with immigrant Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(1), 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR (2000). The case against race profiling in immigration enforcement. Washington University Law Quarterly 78(3), 676–736. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Andrews K, Stein GL, Supple AJ, & Gonzalez LM (2013). Socioeconomic stress and academic adjustment among Asian American adolescents: The protective role of family obligation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(6), 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli A, Markowitz PL, & Chavez L (2011). Secure communities by the numbers: An analysis of demographics and due process. The Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J (2007). Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, & Heim C (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar C, & Abrego L (2009). Parents and children across borders: Legal instability and intergenerational relations in Guatemalan and Salvadoran families In Foner N (Ed.), Across generations (pp. 160 – 189). New York, NY: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler M, Merrick MT, Klevens J, Ports KA, & Ford DC (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, & Han B (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6), 1–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, & Ross CE (2005). Education, cumulative advantage, and health. Ageing International, 30(1), 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Immigration Statistics. (2014). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2014. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Homeland Security; Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2014 [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Horwitz SM, Fang H, Kuo AA, Wallace SP, & Inkelas M (2009). Documentation status and parental concerns about development in young US children of Mexican origin. Academic Pediatrics, 9(4), 278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JD, Cohn D, Krogstad JM, & Gonzalez-Barrera A (2014). As growth stalls, unauthorized immigrant population becomes more settled. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; Retrieved from https://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/09/03/as-growth-stalls-unauthorized-immigrant-population-becomes-more-settled/. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center, 2015. “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065: Views of Immigration’s Impact on U.S. Society Mixed.” Washington, D.C: September. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, & Johnston HF. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York City, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts YH, Snyder FJ, Kaufman JS, Finley MK, Griffin A, Anderson J, … & Crusto CA (2014). Children exposed to the arrest of a family member: Associations with mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 214–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robjant K, Hassan R, & Katona C (2009). Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(4), 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Flores L, Clements ML, Hwang Koo J, & London J (2017). Trauma and psychological distress in Latino citizen children following parental detention and deportation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(3), 352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero M (2006). Racial profiling and immigration law enforcement: Rounding up of usual suspects in the Latino community. Critical Sociology, 32(2–3), 447–473. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, & Wu CL (1995). The links between education and health. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, & Zehr JL (2005). Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 26(3–4), 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkupinski Quiroga S, Medina DM, & Glick J (2014). In the belly of the beast: Effects of anti-immigration policy on Latino community members. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(13), 1723–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Gonzales N, & Fuligni AJ (2014). Family obligation values and family assistance behaviors: Protective and risk factors for Mexican–American adolescents’ substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(2), 270–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Deardorff J, Gunier RB, Harley KG, Alkon A, Kogut K, & Eskenazi B (2018). Worry about deportation and cardiovascular disease risk factors among adult women: The center for the health assessment of mothers and children of Salinas study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(2), 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Profile American Facts for Features. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff17.pdf

- Wade TJ, Cairney J, & Pevalin DJ (2002). Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 190–198. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walper S (2009). Links of perceived economic deprivation to adolescents’ well-being six years later. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung, 21(2), 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- White R, Liu Y, Nair RL, & Tein JY (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 649–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Suárez Orozco C, & Gonzales RG (2017). Unauthorized status and youth development in the United States: Consensus statement of the society for research on adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27(1), 4–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, & Cook Heffron L (2016). Disrupting young lives: How detention and deportation affect US-born children of immigrants. American Psychological Association: CYF News. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2016/11/detention-deportation.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, (2015). Forgotten citizens: Deportation, children, and the making of American exiles and orphans. New York, NY: Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, & Gulbas LE (2017). Processes of belonging for citizen-children of undocumented Mexican immigrants. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2463–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]