Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether the ‘Surgilig’ technique is safe and effective for the treatment of patients suffering from acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) dislocations graded as Rockwood's type III or higher.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

The failure rate of the “Surgilig” implant was very low (3.5%), while patients’ satisfaction was high (88.3%). However, the quality of most studies was low.

Conclusions

There is low evidence to show that the reconstruction of ACJ dislocations with the ‘Surgilig’ technique could be a safe and effective treatment.

Keywords: Acromioclavicular joint dislocation, Braided polyester synthetic ligament, Surgilig technique, LockDown technique, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint and coracoclavicular (CC) ligament injuries are common in active individuals and commonly occur with a fall on the affected acromion with the shoulder in an adducted position.26 The treatment is divided into conservative and operative, depending on the type and severity of injury, acute or chronic form, age, initial level of activity and comorbidities. Conservative treatment generally involves immobilization of the arm with a sling, a brace or strapping.20 After a short period of immobilization, lasting around two weeks, gradual mobilization is started.20

Most surgical procedures regarding the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) primarily involve fixation of the joint and reconstruction of the CC ligament.7 The acromioclavicular joint can be re-approximated using one of three stabilization techniques: (1) primary fixation across the acromioclavicular joint, (2) secondary stabilization of the joint by recreating the anatomic linkage between the distal clavicle and the coracoid process, or (3) dynamic stabilization of the joint by creating an inferiorly directed force on the distal clavicle.11 The hook plate, the ACJ transfixion with K-wires (Phemister technique) and the coracoclavicular (CC) fixation with a screw (Bosworth technique) are recognized as non-anatomic procedures related to high rates of fixation failures and complications.23 An increasing number of studies have revealed that subacromial portion of the hook, when using hook plate as method of treatment, may induce acromial bony erosion, shoulder impingement, or even rotator cuff damage.14,17 Another drawback of the rigid fixation methods is that a second operation is required in order to remove the hardware.

Biomechanical studies have demonstrated the importance of anatomical reconstruction of the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments in cases of unstable ACJ injuries.12 This importance lies in the fact that the conoid and trapezoid ligaments have different functions, which depend on their anatomical location and orientation.18The clinical evidence, although limited, suggests that anatomical ligament reconstruction with autograft or certain synthetic grafts may have better outcomes than non-anatomical transfer of the coracoacromial ligament.15 It has been suggested that this is due to better restoration of the horizontal and vertical stability of the joint.15

A synthetic ligament device called Surgilig™ (Surgicraft LTD, Nottingham, UK) has become available and been successfully used since 2001.21 This prosthetic ligament is a double braided polyester mesh with loops at either end.25 The soft loop is initially passed through the hard loop and then anchored into the clavicle with a bone screw, reducing the clavicle to its normal alignment.27

A number of clinical trials have depicted promising results for the treatment of patients with Rockwood grade≥3, mainly chronic ACJ dislocations with the use of this device. Although the “Surgilig” was initially used in revision ACJ stabilization operations, more recently this method has gained popularity as the primary operation, where it appears to have a lower failure rate than other augments.24 According to a recent national survey in UK about the current practice in the management of Rockwood type III acromioclavicular joint dislocations, the “Surgilig” technique (or more recently called as “LockDown” technique; Lockdown Medical, Reddich, UK) was the most widely used operative technique in all groups of patients.5 However, there are still concerns about the use of an artificial ligament, which are related to the biotolerability of the foreign material.4

The purposes of this systematic review were twofold: 1) To summarize failure rates, complications' rates, patients’ satisfaction, clinical, functional and radiographic outcomes associated with the use of “Surgilig”, and 2) To characterize the methodological quality of the relevant, available literature. Our hypothesis was that “Surgilig” implantation would be proven a safe and effective treatment for the aforementioned patients.

2. Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Two reviewers independently conducted the search using the MEDLINE/PubMed, Google Scholar and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. These databases were queried with the terms “acromioclavicular” AND “joint” AND “dislocation” AND “operative”. To maximize the search, backward chaining of reference lists from retrieved papers was also undertaken. A preliminary assessment of only the titles and abstracts of the search results was initially performed. The second stage involved a careful review of the full-text publications.

Inclusion criteria were: 1) prospective or retrospective clinical studies, 2) recorded follow-up: clinical and/or functional and/or radiographic outcomes, 3) international publication in English, 4) published by June 7th, 2018 (end of our search), 5) use of the ‘Surgilig’ technique for the reconstruction of chronic or acute ACJ dislocation, Rockwood type: III or higher, 6) full-text articles. Exclusion criteria included 1) full text was not available, 2) animal and preclinical studies, 3) studies not written in English, 4) studies without any follow-up assessment, 5) clinical studies not dealing with the ‘Surgilig’ technique, but with other means of treatment (conservative, hook plate, other loop suspensory devices, tightrope, single or double endobutton, absorbable sutures, K-wires, coracoclavicular or acromioclavicular screw fixation, tendon grafts etc.), 6) editorial comments, 7) technical notes, 8) use of the ‘Surgilig’ technique in other anatomic regions (elbow), and 9) papers published before 2001 (year when the “Surgilig” implant was available) and after June 7th, 2018.

Differences between reviewers were discussed until agreement was achieved. In case of disagreement, the senior author would be responsible for the final determination. The reviewers independently extracted data from each study and assessed variable reporting of outcome data. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each study and parameters analyzed. The methodological quality of each study and the different types of detected bias were assessed independently by each reviewer with the use of modified Coleman methodology score and a mean value was calculated per study.19 In addition, the overall quality of the studies was graded according to the GRADE Working Group guidelines.1 Selective reporting bias like publication bias was not included in the assessment. The primary outcome measure was the survival rate of the implant, complications' rates and patients’ satisfaction with their treatment. Secondary outcome variables were the improvement in the clinical and functional subjective scores and the postoperative radiographic persistence of the ACJ stabilization with the synthetic ligament.

3. Results

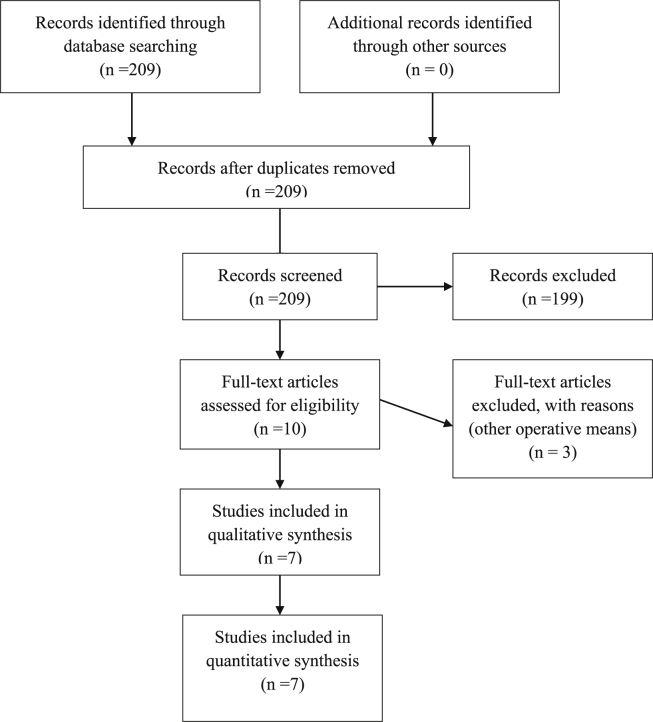

From the 209 initial studies we finally selected and assessed seven clinical studies which were eligible to our inclusion-exclusion criteria.2,3,8,10,24,25,27 We excluded all trials which were dealing with therapeutic means other than the “Surgilig” (49), studies published before 2001 (83), literature reviews (25), articles written in Chinese (9) or German (6) or Czech (1) or Polish (1) or Russian (1) language, case reports (8), irrelevant studies (8), preclinical studies (4), articles without any clinical/functional/radiographic outcome (4), technical notes (2), and editorial comments (1). A summary flowchart of our literature search according to PRISMA guidelines can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow chart.

The vast majority of the studies were classified as level of evidence IV (85.7%),2,3,8,24,25,27 while one study was level II (14.3%).10 Two out of the seven papers (28.6%) of the present review were comparative,10,27 whereas most studies (71.4%) were not controlled.2,3,8,24,25 No one of the studies (0%) was randomized (Table 1).

Table 1.

Type of study, level of evidence, modified Coleman methodology score, and type of potential bias.

| Author(s) | Type of study | Level of Evidence | Modified Coleman Score (0–100) | Type of possible bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al.10 | Prospective Comparative study | II | 72 (Part A: 47 Part B: 25) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Wright et al.25 | Retrospective Case Series | IV | 46 (Part A: 30 Part B: 16) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Jeon et al.8 | Retrospective Case Series | IV | 41 (Part A: 21 Part B: 20) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Bhattacharya et al.2 | Prospective Cohort Study | IV | 56 (Part A: 40 Part B: 16) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Carlos et al.3 | Prospective Cohort Study | IV | 58 (Part A: 42 Part B: 16) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Wood et al.24 | Prospective Cohort Study | IV | 53 (Part A: 40 Part B: 13) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

| Younis et al.27 | ‘Surgilig’ subgroup cohort as part of a case-control study | IV | 43 (Part A: 30 Part B: 13) |

Selection, Performance, Detection, Attrition |

The modified Coleman methodology score ranged from 41/10015 to 72/100.10 The quality of the studies, as it was graded according to the GRADE Working group guidelines,1 ranged between low2,3,8,24,25,27 and moderate.10 All seven studies (100%) were suspicious for selection, detection, performance and attrition bias.2,3,8,10,24,25,27 (Table 1).

The aforementioned studies included 178 patients in total. The mean age was 39.8 years (range: from 35.1 years2 to 43 years25), whereas the vast majority (84.5%) of the patients were males. The mean follow-up was 29.5 months (range: from six months24 to 55 months8). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Number of patients, sex, mean age, mean follow-up, type of lesion, and type of surgery.

| Author(s) | Number of patients | Sex | Mean age (years) | Mean Follow-up (months) | Type of Lesion | Type of operation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al.10 | Group A:31 (Modified Weaver-Dunn) Group B:24 (Surgilig) |

N/A | 42.0 | Group A: 47 Group B: 30 |

Chronic acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Modified Weaver-Dunn Vs Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament |

| Rockwood grade III: 38 (Group A: 25 Group B: 13) | ||||||

| Rockwood grade IV: 8 (Group A: 4 Group B: 4) | ||||||

| Rockwood grade V: 9 (Group A: 2 Group B: 7) | ||||||

| Wright et al.25 | 21 | Male | 43 | 30 | Acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament + Distal Clavicle Excision |

| Rockwood grade III: 12 | ||||||

| Rockwood grade IV: 1 | ||||||

| Rockwood grade V: 8 | ||||||

| Jeon et al.8 | 11 | Male | 39 | 55 | Chronic Acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament |

| Rockwood grade III: 9 (3 had undergone a failed previous Weaver-Dunn procedure) | ||||||

| Rockwood grade IV: 1 | ||||||

| Rockwood grade V: 1 | ||||||

| Bhattacharya et al.2 | 11 | Male | 35.1 | 24 | Chronic Acromioclavicular joint dislocation Rockwood grade III |

Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament + Distal Clavicle Excision |

| 10 | ||||||

| Female | ||||||

| 1 | ||||||

| Carlos et al.3 | 45 | Male | 37.6 | 26.9 | Acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament + Distal Clavicle Excision |

| 32 | Rockwood grade III:16 | |||||

| Female | Rockwood grade IV: 4 | |||||

| 13 | Rockwood grade V: 25 | |||||

| Wood et al.24 | 10 | N/A | N/A | 6 | Chronic Acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Modified Weaver-Dunn augmented with the use of synthetic ligament |

| Younis et al.27 | 22 | Male | 41.4 | 32.6 | Acute and Chronic Acromioclavicular joint dislocation | Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction with the use of synthetic ligament |

| 19 | ||||||

| Female | ||||||

| 3 |

3.1. Type of ACJ injury

Four out of the seven studies (57.1%) which were included in this review dealt with patients suffering from chronic ACJ instability.2,8,10,24 One study (14.3%)27 assessed both acute and chronic ACJ dislocations and two studies (28.6%) did not mention whether they investigated chronic and/or acute ACJ injuries.3,25 The most common type of ACJ injury was Rockwood type III (56.8% of the patients), while a little bit less than one third (32.6%) of the patients were graded as Rockwood type V and 10.6% of the patients as Rockwood type IV.3,8,10,25 (Table 2).

3.2. Type of surgery

Three studies of this review (42.9%) evaluated patients who were treated with ACJ reconstruction with synthetic ligament and distal clavicle excision,2,3,12 whereas three other studies (42.9%) illustrated the outcomes of ACJ reconstruction without distal clavicle excision.8,10,24,25 One study (14.3%) compared the outcome of the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure with that of the “Surgilig” technique,10 while another study (14.3%) assessed the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure as it was augmented with the use of “Surgilig”.24 (Table 2).

3.3. Clinical and functional outcome variables

While all studies of this review reported mean final postoperative clinical/functional subjective scores, only one study documented the respective mean preoperative values.10 The mean final postoperative Oxford Shoulder Score, which was utilized in four studies (57.1%), ranged between 83.1 and 92.3.3,10,25,27 The mean final postoperative Constant score, as deployed in three studies (42.9%), ranged between 39.6 and 45.3.2,8,25 The mean Imatami score, was utilized in two studies (28.6%).2,8 Jeon et al. graded the outcome of seven patients as excellent, three patients were graded as good and one patient as poor.8 Bhattacharya et al. used the quantitative version of the Imatami score and found that the final mean score was 81.2 (ranged between 51 and 98).2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean preoperative and postoperative clinical/functional scores, imaging and other outcome variables, and “take-home-message”.

| Author(s) | Preoperative Mean Scores | Postoperative Mean Scores | Statistical Improvement from pre- to post-operative scores | Imaging Variables | Other Variables | Complications | “Take home message” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al.10 | Group A | Group A | Yes (for all scores) Statistically significant difference between the 2 groups for both scores |

N/A | Return to work Group A vs Group B 14weeks vs 6 weeks (p < 0.001) Return to sports Group A vs Group B 25 weeks vs 12 weeks (p < 0.001) |

1 patient (Surgilig Group): mid-substance rupture of the synthetic ligament after a fall 3 patients (Modified Weaver-Dunn Group): Persistent pain and ACJ re-dislocation |

Better clinical scores and earlier return to work and sports were achieved with the use of the synthetic ligament for acromioclavicular joint reconstruction, compared with the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure. |

| Oxford Shoulder Score | Oxford Shoulder Score | ||||||

| 28 ± 11 | 42 ± 10 (p:0.009) | ||||||

| Nottingham Clavicle Score | Nottingham Clavicle Score | ||||||

| 53 ± 12 | 81 ± 23 (p:0.047) | ||||||

| Group B | Group B | ||||||

| Oxford Shoulder Score | Oxford Shoulder Score | ||||||

| 26 ± 9 | 45 ± 7 (p:0.007) | ||||||

| Nottingham Clavicle Score | Nottingham Clavicle Score | ||||||

| 51 ± 11 | 93 ± 13 (p:0.023) | ||||||

| Wright et al.25 | N/A | Constant Score | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | N/A | 20 patients were satisfied with the procedure Abduction Power 82% of the normal side |

1 patient: developed scapulothoracic bursitis 1 patient: sustained ACJ re-dislocation after a fall |

The synthetic ligament achieved good outcome for patients undergoing stabilization for the disrupted ACJ |

| 86.8 (62–100) | |||||||

| Oxford Shoulder Score | |||||||

| 43.1 (28–48) | |||||||

| Jeon et al.8 | N/A | Constant Score | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | Postoperative radiographs at latest follow-up showed minor subluxation of the clavicle in 10 patients | 9 patients were satisfied with the procedure Return to work 5 weeks (range, 2–10) |

1 patient: had a coracoid base fracture after heavy lifting in the early postoperative period | The synthetic ligament is a useful alternative for the treatment of chronic acromioclavicular separation, especially in revision reconstruction where the coracoacromial ligament is no longer available |

| 92.3 (64–100) | |||||||

| Imatani Score | |||||||

| Excellent: 7 patients | |||||||

| Good: 3 patients | |||||||

| Poor: 1 patient | |||||||

| Bhattacharya et al.2 | N/A | Constant Score | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | Postoperative radiographs showed lucency around the clavicular screw in 4 patients | 9 patients were satisfied with the procedure | 1 patient sustained a mid-substance rupture of the synthetic ligament 1 patient complained of discomfort around the clavicular screw |

The synthetic ligament achieved good outcome for patients undergoing stabilization for chronic ACJ dislocation |

| 83.1 (61–100) | |||||||

| Imatani Score | |||||||

| 81.2 (51–98) | |||||||

| Walsh Score | |||||||

| 14.1 (8–20) | |||||||

| Carlos et al.3 | N/A | Oxford Score | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | Postoperative radiographs at latest follow-up showed migration of the clavicle in 13 patients | 91% of patients were satisfied with the procedure | 1 patient: displacement of the synthetic ligament 6 patients: clavicular screw removal because of skin irritation |

The synthetic ligament appears to be successful for treating both acute and chronic injuries of the ACJ with high patient satisfaction and minor complications |

| 45.31 (35–48) | |||||||

| UCLA Score | |||||||

| 31.38 (11–35) | |||||||

| Simple Shoulder Score | |||||||

| 10.92 (6–12) | |||||||

| Wood et al.24 | N/A | N/A | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | There was no incidence of radiological failure of the graft | All patients returned to their pre-injury level of activities | There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications | The synthetic ligament can be used to augment a Modified Weaver-Dunn procedure without any postoperative complications |

| Younis et al.27 | N/A | Oxford Shoulder Score | There was no assessment of the preoperative function | N/A | 17 patients were happy with their outcome | 2 patients required removal of the clavicular screw due to discomfort and irritation of the overlying skin | The synthetic ligament appears to be effective in treating both acute and chronic acromioclavicular joint dislocations |

| 39.6 (18–48) | 2 patients developed osteolysis of the posterior end of the clavicle |

The mean final postoperative Nottingham Clavicle score, was reported in one study (14.3%).10 The mean final postoperative University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Shoulder Score and the Simple Shoulder Score, as they were documented in one study (14.3%), were 31.4 (range: 11–35) and 10.9 (range: 6–12), respectively.3 The Walsh score was also used in one study (14.3%).2 Bhattacharya et al. found that the mean final postoperative Walsh score was 14.1 (range: 8–20).2 (Table 3).

3.4. Imaging outcome variables

Four out of seven studies of this review reported imaging outcome variables (57.1%).2,3,8,24 Minor subluxation or migration of the clavicle was observed in 29.9% of the patients who were included in the just abovementioned studies2,3,8,24 at their final postoperative follow-up. One study reported four cases (5.2% of the patients who were radiographically assessed) with radiolucency around the clavicle screw.2 (Table 3).

3.5. “Surgilig” technique versus modified Weaver-Dunn

One study (14.3%) investigated the clinical outcomes of two different operative techniques: the “Surgilig” and the modified Weaver-Dunn.10 Regarding the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure, from mean preoperative Oxford Shoulder Score and Nottingham Clavicle Score, 28 (standard deviation: SD:±11) and 53 (SD:±12), respectively, Kumar et al. documented final postoperative mean values of 42 (SD:±10; p:0.009) and 81 (SD:±23; p:0.047), respectively.10 As for the “Surgilig” treated group, the mean preoperative Oxford Shoulder Score and Nottingham Clavicle Score were found 26 (SD:±9) and 51 (SD:±11), respectively, while the mean postoperative Oxford Shoulder Score (45 ± 7) and Nottingham Clavicle Score (93 ± 13) were found significantly improved (Oxford Shoulder Score: p:0.007; Nottingham Clavicle Score: p:0.023).10 The “Surgilig” technique depicted significantly superior clinical outcomes than the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure.10 Even more, the “Surgilig” technique led to significantly faster return to work (6 weeks versus 14 weeks; p < 0.001) and return to sports (12 weeks versus 25 weeks; p < 0.001) in comparison with the modified Weaver-Dunn technique.10

3.6. “Surgilig” technique versus conservative treatment

There was one study (14.3%) which compared the different outcomes of conservative treatment and the “Surgilig” technique in patients with acute or chronic Rockwood type III ACJ injuries.27 The conservatively-treated group illustrated significantly better Oxford Shoulder Scores than the “Surgilig”-treated group, whereas no significant differences were found in regard to patient's satisfaction and pain27.

3.7. Patients’ satisfaction

Five out of the seven studies (71.4%) reported postoperative patients' satisfaction.2,3,8,25,27 Regarding the ‘Surgilig’-treated patients, 88.3% of the patients reported fully or almost fully satisfied.

3.8. Failure rate and complications

The failure rate of the “Surgilig” implant was found very low (3.5%). The most commonly reported postoperative complication was the irritation of the overlying skin by the screw (6.3%).

4. Discussion

Key finding of this review was that the “Surgilig” technique resulted in satisfactory short-to mid-term clinical and functional outcomes in all studies included. This operative technique might be used instead of rigid fixation methods, like the hook plate, acromioclavicular screws or K-wires, techniques with tendon autografts which are related to donor site morbidity, or methods which make use of the native coracoacromial ligament. Although various methods of stabilizing the disruption of the ACJ have been described using the coracoacromial ligament,6,9,22 the need to preserve this ligament where possible has also been acknowledged in the literature.13 Therefore, the “Surgilig” seems advantageous in comparison with techniques which transfer the coracoacromial ligament like the modified Weaver-Dunn.

As expected, the vast majority of the patients included in this review were young males. These dislocations are much more common in men than in women,16 perhaps because men are more likely to practice contact sports than women.20

Most clinical researchers dealing with the “Surgilig” technique used it for chronic ACJ dissociations or revision cases.2,8,10,24 Acute primary cases of Rockwood type > III ACJ disruption were mostly treated with other operative means, like direct repair of the disrupted ligaments and open reduction – internal fixation (ORIF) of the dislocated ACJ, while the treatment of acute Rockwood type III is controversial and, therefore, usually nonoperative at the initial stage. Notwithstanding, Younis et al. reported satisfactory outcomes with the “Surgilig”, both in acute and chronic ACJ injuries.27

The distal clavicle excision as an additional procedure for the reduction of the dislocated clavicle was deployed in combination with the “Surgilig” technique in three studies of this review,2,3,25 whereas another three studies did not use it.8,10,24 So, there is still no consensus amongst specialists regarding the necessity of this additional procedure.

The survival rate of this implant was very high, while the overall complications’ rate was very low. Overlying skin irrigation as a result of a prominent clavicle screw was reported as the most common complication and physicians should always be aware of this risk. However, the mean follow-up of the studies was only short-to mid-term and no conclusions can be extracted regarding the long-term outcomes of the “Surgilig” technique. Hence, future clinical studies are required to evaluate the long-term survival rates of this artificial device for the treatment of ACJ dislocations.

The overall patients’ satisfaction with the use of the “Surgilig” technique was found very high. All mean clinical and functional outcomes, which were postoperatively used to assess the therapeutic value of the “Surgilig”, were also high. Nevertheless, all apart from one study10 did not document preoperative mean values, so that no statistical significance could be estimated.

In comparison with the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure, there were limited data illustrating significantly better clinical and functional outcomes with the use of “Surgilig” in chronic, Rockwood type≥3 ACJ dislocations.10 Despite that, we support that future randomized controlled trials are required to confirm these results.

Another possible use of the “Surgilig” implant which resulted in satisfactory clinical/functional outcomes was as an augmentation to the modified Weaver-Dunn procedure.24 However, we do not see the reason why these two well-established techniques should be used in combination when the clinical results of each one separately have been satisfactory.

When compared with conservative treatment for patients suffering by Rockwood type III ACJ injuries, the “Surgilig” technique was not proven superior.27 Nevertheless, while the “Surgilig” is mainly indicated for chronic ACJ dislocations or revision cases, Younis et al. included both acute and chronic injuries, without distinguishing them.13 Even more, the number of patients who consisted the two groups in the study of Younis et al. was rather small and the study might be underpowered.27

Regarding the imaging variable outcomes, there was a relatively high ratio of postoperative minor subluxation or migration of the clavicle. However, the clinical relevance of these radiographic findings remains controversial. Also, no definite conclusions can be made regarding the role of distal clavicle excision as a possible factor that might influence the ACJ stabilization postoperatively, since the results were conflicting.3,8

The total number of patients who were treated with the “Surgilig” technique was small in order to extract definite conclusions regarding the therapeutic value of this treatment. The level of evidence of all studies2,3,8,24,25,27 apart from the one conducted by Kumar et al.,10 was IV. There was not only a complete lack of level I trials, but also no studies were found to be randomized. If we exclude the trial of Kumar et al.,10 the quality assessment, as it was quantified by the modified Coleman methodology score for methodological deficiencies of studies and the GRADE Working Group guidelines, showed that most studies of this review were of low quality. Even more, all trials were submitted to a high risk of possible performance, selection, detection and attrition bias, which could have compromised their results.

5. Conclusions

There is low evidence to show that the reconstruction of ACJ dislocations with the ‘Surgilig’ technique could be a safe and effective treatment, which might combine high rates of patients' satisfaction with low failure rate. Further clinical trials of higher quality are required for the assessment of this type of treatment.

Conflicts of interest

MM, TS, EB, DG, GA and EA declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2019.09.011.

Contributor Information

Michael-Alexander Malahias, Email: malachiasm@hss.edu.

Thomas Sarlikiotis, Email: tsarliki@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Atkins D., Best D., Briss P.A., GRADE Working Group Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharya R., Goodchild L., Rangan A. Acromioclavicular joint reconstruction using the Nottingham Surgilig: a preliminary report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(2):167–172. Apr. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlos A.J., Richards A.M., Corbett S.A. Stabilization of acromioclavicular joint dislocation using the ‘Surgilig’ technique. Shoulder Elb. 2011;3(3) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chouhan D.K., Saini U.C., Dhillon M.S. Reconstruction of chronic acromioclavicular joint disruption with artificial ligament prosthesis. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(4):216–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domos P., Sim F., Dunne M., White A. Current practice in the management of Rockwood type III acromioclavicular joint dislocations-National survey. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017;25(2) doi: 10.1177/2309499017717868. May-Aug. 2309499017717868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumontier C., Sautet A., Man M., Apoil A. Acromioclavicular dislocations: treatment by coracoacromial ligamentoplasty. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1995;4:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geaney L.E., Miller M.D., Ticker J.B. Management of the failed AC joint reconstruction causation and treatment. Sport. Med. Arthrosc. 2010;18:167–172. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181eaf6f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon I.H., Dewnany G., Hartley R., Neumann L., Wallace W.A. Chronic acromioclavicular separation: the medium term results of coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction using braided polyester prosthetic ligament. Injury. 2007;38(11):1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.05.019. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S., Sethi A., Jain A.K. Surgical treatment of complete acromioclavicular dislocation using the coracoacromial ligament and coracoclavicular fixation : report of a technique in 14 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9:507–510. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199509060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar V., Garg S., Elzein I., Lawrence T., Manning P., Wallace W.A. Modified Weaver-Dunn procedure versus the use of a synthetic ligament for acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2014;22(2):199–203. doi: 10.1177/230949901402200217. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon Y.W., Iannotti J.P. Operative treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries and results. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(03)00005-x. Apr. (vi) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.J., Nicholas S.J., Akizuki K.H., McHugh M.P., Kremenic I.J., Ben- Avi S. Reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments with tendon grafts: a comparative biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:648–654. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee T.Q., Black A.D., Tibone J.E., McMahon P.J. Release of coracoacromial ligament can lead to glenohumeral laxity : a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2001;10:68–72. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.111138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin H.Y., Wong P.K., Ho W.P., Chuang T.Y., Liao Y.S., Wong C.C. Clavicular hook plate may induce subacromial shoulder impingement and rotator cuff lesion--dynamic sonographic evaluation. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;6(9):6. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-9-6. Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modi C.S., Beazley J., Zywiel M.G., Lawrence T.M., Veillette C.J. Controversies relating to the management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Bone Joint Lett J. 2013;95-B(12):1595–1602. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.31802. Dec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pallis M., Cameron K.L., Svoboda S.J., Owens B.D. Epidemiology of acromioclavicular joint injury in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2072–2077. doi: 10.1177/0363546512450162. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renger R.J., Roukema G.R., Reurings J.C., Raams P.M., Font J., Verleisdonk E.J. The clavicle hook plate for Neer type II lateral clavicle fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(8):570–574. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318193d878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rios C.G., Arciero R.A., Mazzocca A.D. Anatomy of the clavicle and coracoid process for reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:811–817. doi: 10.1177/0363546506297536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambandam S.N., Gul A., Priyanka P. Analysis of methodological deficiencies of studies reporting surgical outcome following cemented total-joint arthroplasty of trapezio-metacarpal joint of the thumb. Int Orthop. 2007;31(5):639–645. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0240-6. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamaoki M.J.S., Belloti J.C., Lenza M. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8:CD007429. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007429.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taranu R., Rushton P.R., Serrano-Pedraza I., Holder L., Wallace W.A., Candal-Couto J.J. Acromioclavicular joint reconstruction using the LockDown synthetic implant: a study with cadavers. Bone Joint Lett J. 2015;97-B(12):1657–1661. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B12.35257. Dec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tienan T.G., Oyen J.F., Eggen P.J. A modified technique of reconstruction for complete acromioclavicular dislocation : a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:655–659. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warth R.J., Martetschläger F., Gaskill T.R., Millett P.J. Acromioclavicular joint separations. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;6:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood T.A., Rosell P.A., Clasper J.C. Preliminary results of the 'Surgilig' synthetic ligament in the management of chronic acromioclavicular joint disruption. J R Army Med Corps. 2009;155(3):191–193. doi: 10.1136/jramc-155-03-03. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright J., Osarumwense D., Ismail F., Umebuani Y., Orakwe S. Stabilisation for the disrupted acromioclavicular joint using a braided polyester prosthetic ligament. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2015;23(2):223–228. doi: 10.1177/230949901502300223. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wylie J.D., Johnson J.D., DiVenere J., Mazzocca A.D. Shoulder acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligament injuries: common problems and solutions. Clin Sports Med. 2018;37(2):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.12.002. Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Younis F., Ajwani S., Bibi A., Riley E., Hughes P.J. Operative versus non-operative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint dislocations and the use of SurgiLig: a retrospective review. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2017;19(6):523–530. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.8043. Dec 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.