Introduction

Management of life threatening hematuria can pose a therapeutic challenge especially if it affects a child. This challenge escalates manifold when the child is suffering from Klippel-Tre‘naunay syndrome (KTS); which is characterised by capillary, venous and lymphatic malformations, varicose veins and unilateral soft and skeletal tissue hypertrophy. The hematuria in such a patient is usually due to infiltration of the bladder by the vascular malformations which in turn are found to be communicating with the extensive extravesical lesions, thereby posing a surgical challenge. We, herein, report such a rare case managed successfully at our centre.

Case report

A 14 year old female patient, a diagnosed case of KTS since two months of age was admitted with gross total painless hematuria of 05 days duration. This was associated with giddiness and easy fatigability. In the past she had been treated for bleeding rectal varicosities, but the problem, although reduced, continued to trouble her intermittently. Physical examination revealed extreme pallor with a palpable bladder. Her Haemoglobin was 4.9 g%. Other biochemical and haematological parameters were normal. Packed cells transfusion was started and an emergency clot evacuation was done cystoscopically. After complete clot evacuation, cystoscopy revealed a large venous malformation infiltrating the dome and right lateral wall of the bladder. There was a diffuse ooze but no active pin point bleeder could be identified.

After stabilisation, MRI and MR Angiogram of the abdomen, pelvis and the right lower limb was done which revealed a large multi-compartmental lympho-venous malformation involving the retroperitoneum on the right side and the pelvis. The malformation was also seen involving the dome of the urinary bladder with extension into the peri-vesical region (Fig. 1) and was also seen to be communicating with those of the right lower limb.

Fig. 1.

MRI picture showing the presence of the infiltrating vascular malformation at the dome of the urinary bladder.

Faced with a management dilemma, embolisation of the bleeding malformation was our first choice. But embolisation was not possible due to lack of specific arterial feeder as revealed by the MR Angiogram. These malformations being lympho-venous in character also precluded the bilateral internal iliac artery ligation, hence radiotherapy was considered. But owing to slower onset of action and prolonged duration of radiotherapy this option was also not considered optimal in this acute setting. Surgery would have been challenging due to the presence of the infiltrating malformations which were intercommunicating. But with the patient bleeding continuously it was decided to go ahead with the surgical management. The Vascular and the reconstructive surgeons were on standby for possible management difficulties and blood was arranged for anticipated loss.

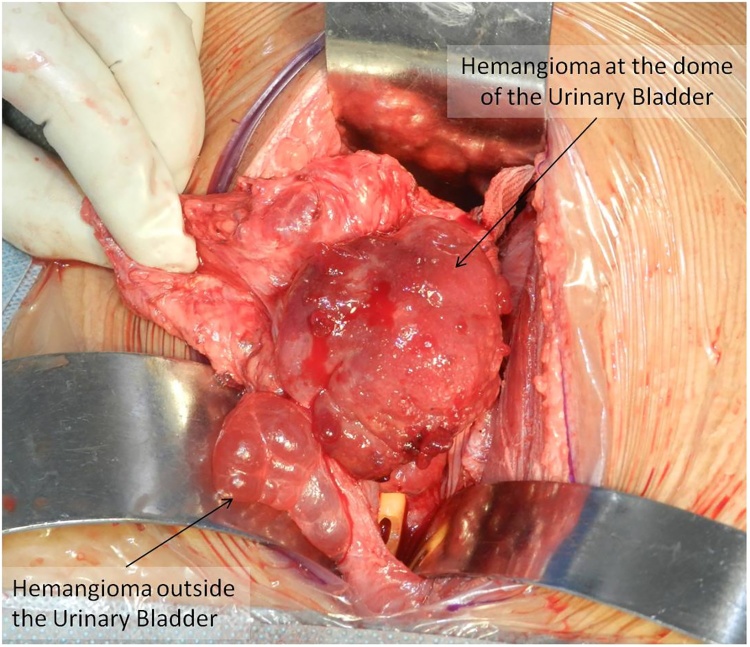

She was taken up for a partial cystectomy through an infraumbilical midline extraperitoneal approach. The malformation on the dome of the bladder was dissected free from all around. An uneventful partial cystectomy was done with a total blood loss of less than 50 ml (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The retroperitoneal malformation was sclerosed with boiling hot saline intra-operatively. The post operative period was uneventful and the patient has remained symptom free on follow up. She is now being worked up for excision of the right lower limb malformation by the reconstructive surgery team.

Fig. 2.

The bladder, after opening, revealing the vascular malformation at the dome.

Fig. 3.

The bladder after the uneventful partial cystectomy.

Discussion

KTS, a rare congenital disorder with an incidence of 3–5/100,0001 is characterised by a combination of vascular malformations, varicose veins and soft and skeletal tissue hypertrophy.2 Of the various genitourinary afflictions, involvement of urinary bladder in KTS is unusual, affecting only 2–6%3 of patients. It can manifest either as occult or gross hematuria which can be life threatening as it happened in present case.3

A CT scan or MRI delineates the lesion best and helps in planning further management. Besides the location, imaging also maps out the extent of the lesions, associated vascular malformations, and infiltration of deeper tissues. Cystopanendoscopy can confirm the bladder and urethral involvement. Bladder lesions are usually located at the anterior wall or dome as was seen in the present case.3

Selective arterial embolisation, Cystoscopic ablations/cauterizations, radiotherapy ablation and open surgical excision are the various treatment options available. Initial management of hematuria, however, remains conservative; with thorough bladder wash.4 A bilateral internal iliac artery embolisation can be attempted, but frequent development of collaterals leading to recurrence, and infarcts in bladder have been described in literature.5 Radiotherapy, also a modality to deal with the vascular malformations, is not favoured due to its temporary benefit in addition to causing massive morbidity.6 In our case open surgical excision was performed because of unsuitability of other less invasive procedures.

Patients with KTS should be monitored at least annually and more frequently if symptoms are present. If there is a progression of disease, imaging studies should be repeated, and proper intervention carried out if indicated.7

Conclusion

KTS is a rare congenital vascular condition which may occasionally involve the urogenital tract and manifest as life threatening hematuria. A multi-speciality cohesive approach may be required to tackle this condition. Surgery for bladder lesions, in the form of a partial cystectomy, may be challenging, but offers a chance to cure and should be performed when other modalities are either not suitable or have failed.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Oduber C.E., van der Horst C.M., Hennekam R.C. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: diagnostic criteria and hypothesis on etiology. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:217–223. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318062abc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob A.G., Driscoll D.J., Shaughnessy W.J., Stanson A.W., Clay R.P., Gloviczki P. Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome: spectrum and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:28–36. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63615-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furness P.D., 3rd, Barqawi A.Z., Bisignani G., Decter R.M. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: 2 case reports and a review of genitourinary manifestations. J Urol. 2001;166:1418–1420. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsaros D., Grundfest-Broniatowski S. Successful management of visceral Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome with the antifibrinolytic agent tranexamic acid (cyclocapron): a case report. Am Surg. 1998;64:302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato M., Chiba Y., Sakai K., Orikasa S. Endoscopic neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser irradiation of a bladder hemangioma associated with Klippel-Weber syndrome. Int J Urol. 2000;7:145–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2000.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicente J., Salvador J. Neodymium:YAG laser treatment of bladder hemangiomas. Urology. 1990;36:305–308. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(90)80234-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharat A.T., Bhargava R., Bakshi V., Goyal A. Klippel–trenaunay syndrome: a case report with radiological review. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2016;9:522–526. [Google Scholar]