Abstract

Insulin is a potent anabolic hormone, and binding to its receptor activates downstream intracellular signaling pathways that regulate the nutrient metabolism, fluid homeostasis, growth, ionic transport, maintenance of vascular tone, and other functions. Insulin resistance (IR) is a condition characterized by subnormal cellular response to physiological levels of insulin. The IR is divided into three types (prereceptor, receptor, and postreceptor) based on the site of pathology. Beta cells attempt to overcome the IR by increasing the release of insulin, leading to hyperinsulinemia. IR is the predisposing factor for many metabolic and cardiovascular disorders. From the evolutionary perspective, the presence of IR offers a survival advantage in the face of starvation or stress. In this brief review, we discuss the different facets of insulin resistance and appraise the readers about the hitherto neglected beneficial advantages.

Keywords: Polycystic ovarian disease, Diabetes, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Insulin resistance, Lifestyle disease

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) is characterized by the suboptimal physiological response to the normal insulin concentration in various tissues. Metabolic and mitogenic pathways are the two major intracellular pathways that mediate the intracellular action of insulin.1 There is a dissociation between these two pathways in IR, the former being affected in most tissues. IR is a common abnormality and provides the basis for subsequent development of the metabolic, cardiovascular, and endocrine disorders.2 The syndromic forms of IR have the typical manifestations of the acanthosis nigricans, hyperandrogenism, and lipodystrophy.3 During caloric excess states, the cells dampen the insulin receptor signaling to resist the anabolic effects of glucose. This impaired signaling is the key mediator for the lack of suppression of fatty acid release from the adipocytes and deficient nitric oxide (NO) release. A number of internal organs and physiological systems are affected by IR and the consequent hyperinsulinemia.

The ugly face

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the commonest non-communicable disease that is prevalent in both developed and developing regions with similar frequency. Genetic risk and IR are the two key risk factors implicated for the T2DM pandemic.4 In the presence of IR, the pancreatic beta cells enhance their insulin secretion to address the fuel load. This high rate of beta cell metabolism leads to intracellular stress and mitochondrial damage. The exposure to high levels of fatty acids and inflammatory mediators in the background of stress induced by hyperfunctioning eventually leads to exhaustion of the beta cells and T2DM. The studies from the Pima Indians have shown that IR coupled with beta cell dysfunction is the key pathogenic mechanisms leading to T2DM.5 A large number of adipocytokines act as proinflammatory mediators of IR, leading to T2DM.6 The rise in obesity, sedentary lifestyle, westernization of diet, and low birth weight lead to increase in IR in children and also occurrence of early-onset T2DM in India.7 There are a number of polymorphisms described in the genes involved in the beta cell growth and differentiation. The genetic factors increase the susceptibility of the beta cells from the damage in the backdrop of IR culminating into T2DM.

The bad face

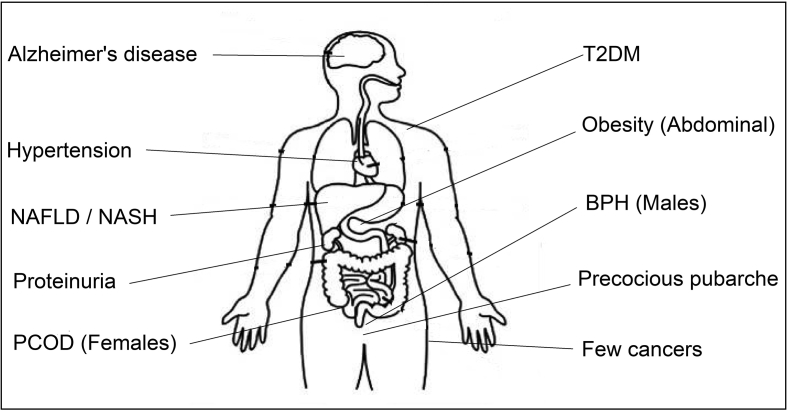

The spectrum and organ involvement of IR extends way beyond T2DM, as shown in Fig. 1. The disorders that have direct links with IR extend from the pediatric to geriatric population. Premature pubarche (PP) is defined as the appearance of pubic hair in girls younger than 8 years and in boys younger than 9 years. Recent data suggest that PP is a forerunner of ovarian hyperandrogenism of adolescence and polycystic ovarian disease (PCOD) in adults. Insulin directly stimulates androgen production from ovarian theca cells and also amplifies the luteinizing hormone response of granulosa cells, leading to abnormal differentiation and early maturation arrest of the follicles.8 Insulin also inhibits the production of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) from the hepatocytes. PCOD is a common metabolic disorder in the women of reproductive age, and the affected women have marked IR, independent of body weight. PCOD is a complex genetic disease, and the male equivalent of PCOD is early-onset (younger than 35 years) androgenetic alopecia.9

Fig. 1.

Spectrum of insulin resistance. PCOD, polycystic ovarian disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is another common accompaniment of IR. Insulin facilitates the storage of glucose as glycogen in the liver and also the lipids as triglycerides in adipose tissue. IR leads to the elevation of free fatty acids (FFAs) and lipid deposition in hepatocytes.10 The associated inflammatory cytokines lead to steatohepatitis and liver failure. The cardiac involvement of the IR is complex and multifactorial. Fatty acids are the primary energy substrate for cardiac tissue. IR-induced excess FFA delivery to the heart results in cardiomyocyte dysfunction and oxidative stress. Advanced glycation end products also damage the cardiac insulin signaling pathway and contribute to myocardial dysfunction.11 IR impairs NO-mediated vasorelaxation and also accelerates atherosclerosis by macrophage accumulation.

Diabetic nephropathy is the commonest cause of end-stage kidney disease, and syndromic forms of IR result in a different type of renal disease. The renal pathology includes proteinuric disorders such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and a variant similar to lupus nephritis.12 IR has been implicated as one of the risk factors for many solid organ cancers. The growth-promoting actions of insulin are mediated through insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). Hyperinsulinemia leads to increase in IGF-1 and reduction in the SHBG, thereby increasing the levels of the circulating sex steroids. IR has been implicated as an independent risk factor for the hormone-responsive breast and endometrial cancer.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterized by neuronal IR, impaired synaptic plasticity, and loss of synapse.13 Type 3 diabetes is the proposed term for AD, which results from IR in brain tissue. Recent research has suggested that migraineurs have increased cardiovascular risk that is contributed by the underlying IR.14 Insulin receptors are widely present in neuronal tissues, including the brain, and the pathophysiological links are maintained through the release of NO, leptin, and other neurotransmitters. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and the associated lower urinary tract symptoms are common in elderly men. Multiple mechanisms link IR with BPH and include sympathetic overactivity, increased IGF-1, altered sex steroids, and associated inflammation.15 In addition to the aforementioned described structural changes, IR contributes to the hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia. The classical lipid abnormalities include elevated triglycerides, low high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and increase in the number of the small dense low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol particles.

The good face

Human survival was dependent on efficient energy storage to withstand starvation and the ability to tackle infection and stress by mounting an immune response. Energy storage in fats is mediated by insulin, and mobilization of the stored energy during stress is mediated by inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting the action of insulin in these tissues. The human brain is the major glucose consumer, whereas the peripheral organs may use fatty acids and amino acids also in addition to glucose. In conditions of increased metabolic demands, various hormones and cytokines produce a state of IR in the liver (increased glycolysis) and fat (increased release of the FFAs). This selective peripheral insulin resistance helps in diverting glucose to the brain, and FFAs cover the peripheral energy requirements. IR confers survival benefit in states of starvation to spare glucose for production of nucleotides and NADPH. IR ensures that the vital organs use fatty acids and spare glucose for the brain and other important defense mechanisms.16 Thus, IR is a necessary evil historically when mankind was faced with challenges of famine, undernutrition, and prolonged starvation. However, in the current century, we are saddled with energy surplus situation, and the in-built mechanisms of energy diversion lead to obesity and T2DM. Insulin is a potent anabolic hormone and regulates erythropoiesis. Hyperinsulinemia due to IR could lead to stimulation of erythroid progenitor cells and increase in red blood cell (RBC) mass.17 This is a double-edged benefit as the increase in RBC mass could lead to hemoconcentration, which is an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disorders. Erythropoietin has a synergistic effect with insulin in promoting the survival and differentiation of erythropoietic progenitors.

Conclusion

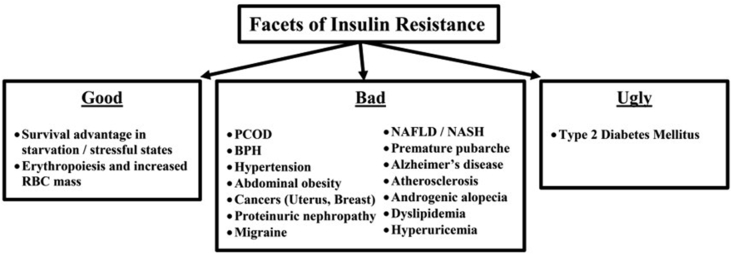

The T2DM pandemic (the ugly) and a host of other metabolic and endocrine disorders (the bad) bear the testimony to the fact the modern human being is living in a chronic stressful environment characterized by the high-energy food intake and low physical activity, as shown in Fig. 2. The evolutionary perspective (the good) helps us to identify the targets in tackling IR by addressing the ectopic lipid deposition and use of irisin that helps in the browning of adipocytes after exercise. The demographic transformation with a nutrient surplus situation is a key factor that needs to be addressed at the community level. Public health measures that have been suggested include a ban on the sale of fast foods in school canteens and the encouragement of the bicycle instead of motor vehicles. IR remains an unconquered evil in the present day, and the battle is fast assuming a one-sided one, with very little pharmacological options available to tackle the same. IR could be protective or damaging depending on the underlying situation and may thus be termed as the equivalent of the “Sword of Damocles.”

Fig. 2.

Facets of insulin resistance. PCOD, polycystic ovarian disease; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Moller D.E., Flier J.S. Insulin resistance – mechanisms, syndromes, and implications. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:938–948. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFronzo R.A., Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991 Mar;14(3):173–194. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semple R.K., Savage D.B., Cochran E.K., Gorden P., O'Rahilly S. Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:498–514. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn S.E., Hull R.L., Utzschneider K.M. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444(7121):840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeRoith D. Beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: role of metabolic and genetic abnormalities. Am J Med. 2002 Oct 28;113(Suppl 6A):3S–11S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esser N., Legrand-Poels S., Piette J., Scheen A.J., Paquot N. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014 Aug;105(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ighbariya A., Weiss R. Insulin resistance, prediabetes, metabolic syndrome: what should every pediatrician know? J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;9(suppl 2):49–57. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.2017.S005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibáñez L., Díaz R., López-Bermejo A., Marcos M.V. Clinical spectrum of premature pubarche: links to metabolic syndrome and ovarian hyperandrogenism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009 Mar;10(1):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11154-008-9096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamanti-Kandarakis E., Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(6):981–1030. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitade H., Chen G., Ni Y., Ota T. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance: new insights and potential new treatments. Nutrients. 2017 Apr 14;9(4) doi: 10.3390/nu9040387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abel E.D., O'Shea K.M., Ramasamy R. Insulin resistance: metabolic mechanisms and consequences in the heart. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012 Sep;32(9):2068–2076. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musso C., Javor E., Cochran E., Balow J.E., Gorden P. Spectrum of renal diseases associated with extreme forms of insulin resistance. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Jul;1(4):616–622. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01271005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neth B.J., Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer's disease: bioenergetic linkages. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017 Oct 31;9:345. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rainero I., Govone F., Gai A., Vacca A., Rubino E. Is migraine primarily a metaboloendocrine disorder? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018 Apr 4;22(5):36. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breyer B.N., Sarma A.V. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance and the risk of BPH/LUTS: an update of recent literature. Curr Urol Rep. 2014 Dec;15(12):462. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0462-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soeters M.R., Soeters P.B. The evolutionary benefit of insulin resistance. Clin Nutr. 2012 Dec;31(6):1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbieri M., Ragno E., Benvenuti E. New aspects of the insulin resistance syndrome: impact on haematological parameters. Diabetologia. 2001 Oct;44(10):1232–1237. doi: 10.1007/s001250100634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]