We read with great interest the recent paper of Zhou et al. (1) which describes a promising low-input protocol for measuring secreted RNA in blood. Zhou et al. (1) apply this technology to 96 samples of serum from cancer patients (28 with recurrence, 68 without) and 32 samples of serum from healthy controls. In the face of high noise (r2 ∼ 0.5 over 12 log-orders), the cohorts can be distinguished with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of >0.95 on the basis of extracellular RNA. This classification performance is stronger than what has been observed in circulating tumor cells (2), so we sought to understand the nature of the extracellular cancer signal.

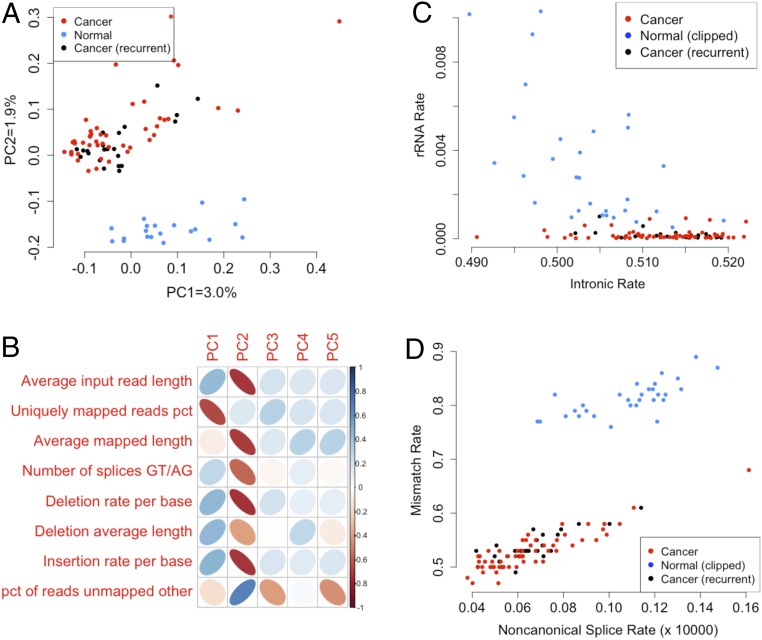

Reanalysis of the raw data demonstrated a perfect confound between read length and cancer status (50 base pairs [bp] for both cancer cohorts, 75 bp for normal). Raw expression principal components PC1 and PC2, which separate cancer from normal samples, highly correlate to alignment metrics (Fig. 1 A and B). Following in silico read-length trimming, normal samples still exhibited perfect or near-perfect separation along a number of purely technical variables: mismatch rate, intronic rate, exonic rate, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) rate, and others (Fig. 1 C and D). Based on these observations, it seems that serum from individuals with cancer was processed separately from serum from individuals without cancer, creating a perfect confound between library batch, sequencing batch, and status. Since many standard RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technical metrics also stratify by batch, correcting for these technical covariates [which is standard for differential expression analysis (3–6)] results in an inability to predict cancer status.

Fig. 1.

Perfect confounding in extracellular RNA-seq. (A) Kallisto-quantified, uncorrected RNA-seq expression principal components. Serum samples from cancer patients cluster separately from serum drawn from healthy controls. (B) Correlation of the raw expression principal components with standard RNA-seq quality control (QC) metrics, demonstrating very high correlations with input read length and indel rates. (C and D) Example plots of sample-level RNA QC metrics, after clipping to matched read sizes, on which normal and cancer serum samples separate. rRNA depletion appears to have performed significantly better on the batch consisting of serum samples from cancer patients.

Library and sequencing batch are well-known drivers of RNA-seq expression variance (7, 8) that in some studies have been observed to explain the majority of raw expression variance (9, 10). It should be regarded as a very likely case, if not the most likely case, that batch rather than cancer status is the primary driver of the differences observed by the authors.

We do not dispute that Small Input Liquid Volume Extracellular RNA Sequencing reproducibly profiles serum extracellular RNA, nor do we dispute that it has diagnostic potential. However, the perfect confound between status and batch significantly weakens the stated results of the paper. Because of the well-established relationship between both library and sequencing batch and RNA-seq expression, we recommend the experiment be repeated with a careful eye to controlling serum and blood storage conditions and randomization across library and sequencing batch. Furthermore, it should be made clear both in the published paper and in its supplement that the primary outcome was not randomized across either library construction or sequencing batch.

Footnotes

The authors declare a competing interest. Y.G. is a cofounder of Singlera Genomics and Med Data Quest.

References

- 1.Zhou Z., et al. , Extracellular RNA in a single droplet of human serum reflects physiologic and disease states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19200–19208 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan T. T., et al. , A digital RNA signature of circulating tumor cells predicting early therapeutic response in localized and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 8, 1286–1299 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostafavi S., et al. , Normalizing RNA-sequencing data by modeling hidden covariates with prior knowledge. PLoS One 8, e68141 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen Y., Nettleton D., Liu H., Tuggle C. K., Detecting differentially expressed genes with RNA-seq data using backward selection to account for the effects of relevant covariates. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 20, 577–597 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finotello F., Di Camillo B., Measuring differential gene expression with RNA-seq: Challenges and strategies for data analysis. Brief. Funct. Genomics 14, 130–142 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe A. E., et al. , qSVA framework for RNA quality correction in differential expression analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 7130–7135 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman G. E., Schadt E. E., variancePartition: Interpreting drivers of variation in complex gene expression studies. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 483 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oytam Y., et al. , Risk-conscious correction of batch effects: Maximising information extraction from high-throughput genomic datasets. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 332 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leek J. T., et al. , Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 733–739 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papiez A., Marczyk M., Polanska J., Polanski A., BatchI: Batch effect identification in high-throughput screening data using a dynamic programming algorithm. Bioinformatics 35, 1885–1892 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]