Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to explore the association between perceived organizational support (POS) and depressive symptoms, and to further explore whether self-efficacy can act as a moderator between POS and depressive symptoms among Chinese petroleum workers.

Methods

There was a cross-sectional study conducted at a petrochemical enterprise in Liaoning Province, China, from July to August 2018. A series of questionnaires were accomplished by 1836 petroleum workers, including the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS), and the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES). Hierarchical regression analysis was used to examine the relationship of SPOS score, GSES score, and SPOS score×GSES score interaction with CES-D score. A simple slope analysis will be carried out if the interaction has statistical significance.

Results

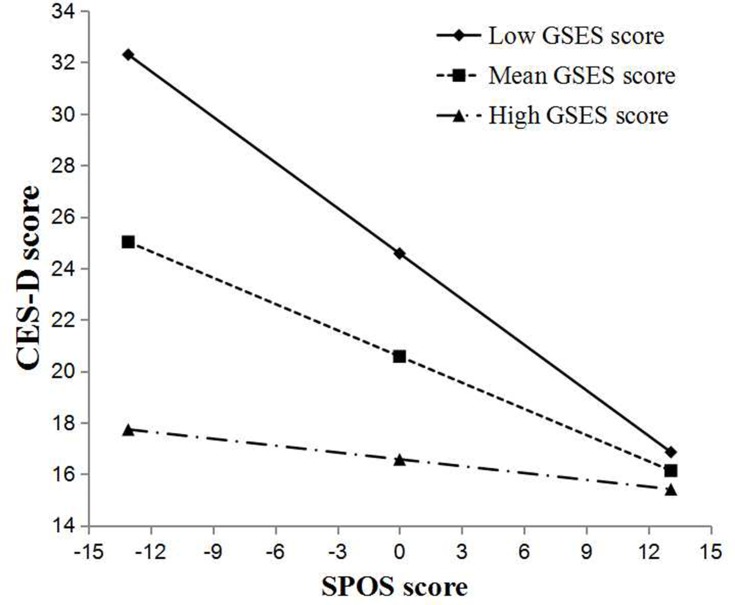

Hierarchical regression analysis showed that SPOS score (β=−0.538, P<0.01) and GSES score (β=−0.313, P<0.01) played a main influence on CES-D score. The SPOS score×GSES score interaction term significantly explained an extra 9.7% of the variance (F=253.932, adjusted R2=0.582, ΔR2=0.097, P<0.01). The interaction term was positively correlated with CES-D score (β=0.334, P<0.01). The relationship between SPOS score and CES-D score gradually decreased in the low (1 SD below the mean, β=−0.589, P<0.01), mean (β=−0.338, P<0.01), and high (1 SD above the mean, β=−0.087, P<0.01) groups of GSES score.

Conclusion

This study showed that POS and self-efficacy played a main influence on depressive symptoms, and the interaction term was positively correlated with depressive symptoms. Self-efficacy could attenuate the association between POS and depressive symptoms. It suggests that appropriate POS and self-efficacy enhancement measures ought to be supplied to relieve depressive symptoms.

Keywords: moderating role, depressive symptoms, perceived organizational support, self-efficacy, petroleum workers

Introduction

Depression is one of the main mental diseases affecting human health.1 The World Health Organization reported an annual prevalence of depression of 9.5% in women and 5.8% in men.2 Depression is also prevalent in the labor force, and the research reports from different countries show that depressive symptoms are common in the workplace.3–5 In recent years, the investigation found that almost half of the occupational groups have depressive symptoms in China,6 including teachers, traffic police, administrators, community health workers, employees of foreign enterprises, and researchers.7 In addition to the high prevalence of depression, it also influences the productivity and overall job performance of workers in the workplace.8 Workers with depression may have higher rates of absenteeism, turnover willingness, and even stoppage.9,10

At present, there are many investigations on depressive symptoms and their psychological factors in different groups in China.11,12 However, few studies have reported the prevalence of depressive symptoms among petroleum workers in China, especially the relationship between coping resources and depressive symptoms. The petrochemical industry has been a high-risk industry, which involves exploration, oil recovery, transportation, processing, deep processing, and other links. Petroleum workers have been exposed to special working conditions for a long time, including kinds of physical stressors, such as bad weather conditions, shifts, night shifts, long working hours, noise, vibration, and poor ventilation.13 These conditions are considered to present a significant effect on physical and mental health.14 Work conditions, including occupational category, shift work, night duty, long working hours, and occupational mental factors, including working pressure, self-efficacy, and perceived social support, have been identified as predictors of depression.15 Therefore, the study of depressive symptoms and related factors in petroleum workers will help to formulate effective intervention measures for the population.

Perceived organizational support (POS) means that employees form a generalized perception concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being.16 POS also fulfills socioemotional needs, resulting in greater identification and commitment to the organization, greater psychological well-being, and workers may be happier in their jobs when they see the organization as dispositionally supportive.17 POS is considered an efficient organizational resource that can produce positive work attitudes and results, and also has a positive impact on people’s mental health.18,19 It has been identified as a positive resource for alleviating depressive symptoms.20,21 It can be concluded that when employees feel high organizational support, they will be more enthusiastic and happy, and the probability of depression will be reduced. At the same time, self-efficacy also has this function. Self-efficacy refers to the belief in one’s competence to cope with a broad range of stressful or challenging demands.22 Self-efficacy can affect a person’s behavior choice and determines the extent and duration of their efforts when a person has to face obstacles or suffering, and self-efficacy also can affect people’s thinking and emotional response patterns.23 Many research studies have shown that self-efficacy has a direct positive impact on depression.24,25 With higher self-efficacy, depressive symptoms became lighter. Also, the mediating role of self-efficacy has been confirmed widely in various groups, including nurses26 and medical students.27 Moreover, self-efficacy can also be used as a “moderator” to enhance or attenuate the impact of stressors or coping resources on psychosocial factors. Zou Tao et al.’s study mentioned that self-efficacy may moderate the relationship between sense of security and depression among the armed soldier population.28 Through Marta Makara-Studzińska et al.’s research, we know that self-efficacy moderated the association between pressure and professional burnout among firefighters.29 Through Gabriele Prati et al.’s research, we know that self-efficacy moderated the relationship between stress appraisal and quality of life among rescue workers.30 In summary, self-efficacy seems to be a related moderator of the relationship between POS and depressive symptoms in petroleum workers.

In conclusion, the aim of the study is firstly to explore the association between POS and depressive symptoms. Secondly, we will further explore whether self-efficacy can attenuate the relationship of POS with depressive symptoms. Finally, we investigated the prevalence of depressive symptoms among petroleum workers in China and propose intervention strategies to relieve depressive symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects and Data Collection

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in a petrochemical industry in northeastern China during the period from July to August 2018. Finally, 2200 workers were randomly selected. After briefly describing the study, we distributed a self-administered questionnaire directly to these workers. Trained investigators helped them complete the questionnaire anonymously. Investigators did not interfere in filling out the questionnaire. In this study, effective responses were received from 1836 (83.5%) workers.

Measurement of Depressive Symptoms

The Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure depressive symptoms.31,32 The 20-item Chinese version of the questionnaire was widely used in Chinese populations and had good reliability and validity.33 The CES-D measured the symptoms 1 week before the questionnaire. Every item has 4 responses with categories ranging from 0 “never” to 3 “always”, and the total score ranged from 0 to 60. Higher average score represents a higher depression level. A standard CES-D score ≥16 presents depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D was 0.895 in this study.

Measurement of Self-Efficacy

The Chinese version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) was used to measure self-efficacy.22 The GSES was widely used in Chinese populations.34,35 The scale consists of 10 items, and according to the personal feelings of the respondents, every item was answered with a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “completely incorrect” to 4 “completely correct”. The total score of the scale ranges from 10 to 40, and a higher average score represents higher self-efficacy. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α alpha for the GSES was 0.76

Measurement of Perceived Organizational Support

The Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS) scale was used to measure perceived organizational support.16 The SPOS scale includes 9 items and focuses on the evaluation and welfare of employees. Every item was answered with a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”. The total score of the scale ranges from 10 to 70, and a higher average score represents higher POS levels. It has been widely used and validated in Chinese professional groups.36 Cronbach’s alpha for the SPOS scale was 0.85 in the present study.

Demographic and Working Factors

In our research, demographic factors comprised age, gender, marital status, educational level, and monthly income. Age was divided into four groups: ≤30, 31–40, 41–50, and ≥51. Educational level was categorized as “senior high school or below” and “technical secondary school or above”. Marital status was classified as “married/cohabited” and “single/divorced/widowed/separated”. Monthly income (RMB) was classified as “<4000” and “≥4000”. Working characteristics including occupational category, night duty, and shift work were collected in our study. The occupational category was categorized as “refinery workers”, “chemical workers”, “transportation workers”, and “other workers”. Night duty and shift work are classified as “no” or “yes”.

Statistical Analysis

Mean, standard deviation (SD), number (n) and percentage (%) were used to describe the demographic, working characteristics, and psychological factors as appropriate. In our study: the independent variable was SPOS score; the dependent variable was CES-D score; the moderator variable was GSES score. The normality of these variables was proved by the Shapiro–Wilk test before statistical analysis. An independent-sample t-test or one-way ANOVA was applied to examine group differences of CES-D score, and Tukey’s test was used for the post-hoc test. Correlations among SPOS score, CES-D score, and GSES score were examined by Pearson’s correlation. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to prove the relationship of SPOS score and GSES score with CES-D score and to examine the moderating role of GSES score on the association of SPOS score with CES-D score. Besides age and gender, the working characteristics associated with CES-D score in univariate analysis (P<0.05) were adjusted. Age, gender, and potential control variables were added in the first step. In the second step, SPOS score and GSES score were added. Finally, the product of SPOS score and GSES score was added in the last step. If the interaction effect had statistical significance, we will conduct simple slope analysis to visualize the interaction term.37 Before the regression analysis, the variables in the models were centralized. All statistical analyses were conducted by IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM, Asia Analytics Shanghai, People's Republic of China), and a two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to have statistical significance.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Demographic and working traits of study variables are presented in Table 1. In our research, 85.4% (1568) workers were married or cohabited. 51.6% (948) of workers had a senior high school or below education level, and there were 59.1% (1085) workers with a monthly income level of <4000 yuan. In all, the difference is statistically significant between occupational categories (F=10.751, P<0.001). 40.6% (746) were refinery workers, and they reported a higher CES-D score than transportation workers (P<0.05). 15.4% (283) were chemical workers, and they reported a higher CES-D score than other workers (P<0.05). 60.5% (1111) of workers had night duty and they reported higher CES-D score (t=16.956, P<0.001) than those who did not have night duty. 53.6% (985) workers had shift work, and they presented a higher CES-D score (t=16.130, P<0.001) compared with workers who did not have shift work.

Table 1.

Demographic and Working Variables of Participants in Relation to CES-D Score

| Variables | n | % | CES-D Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | F/t | P-value | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤30 | 203 | 11.1 | 19.32 | 10.61 | 1.957 | 0.119 |

| 31–40 | 416 | 22.7 | 20.47 | 11.17 | ||

| 41–50 | 863 | 47.0 | 19.29 | 10.32 | ||

| ≥51 | 354 | 19.3 | 18.73 | 10.01 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 1409 | 76.7 | 19.55 | 10.48 | 0.532 | 0.466 |

| Women | 427 | 23.3 | 19.13 | 10.57 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1568 | 85.4 | 19.41 | 10.46 | 0.176 | 0.675 |

| Single/divorced/widowed/separated | 268 | 14.6 | 19.70 | 10.77 | ||

| Education level | ||||||

| Senior high school or below Technical secondary school or above |

948 888 |

51.6 48.4 |

19.40 | 10.25 | 0.043 | 0.836 |

| 19.50 | 10.77 | |||||

| Monthly income (RMB) | ||||||

| <4000 | 1085 | 59.1 | 19.56 | 10.72 | 0.311 | 0.577 |

| ≥4000 | 751 | 40.9 | 19.29 | 10.18 | ||

| Occupational category | ||||||

| Refinery workers | 746 | 40.6 | 20.88a | 10.96 | 10.751 | <0.001 |

| Chemical workers | 283 | 15.4 | 19.75b | 10.28 | ||

| Transportation workers | 355 | 19.3 | 18.72a | 10.13 | ||

| Other workers | 452 | 24.6 | 17.48b | 9.80 | ||

| Night duty | ||||||

| Yes | 1111 | 60.5 | 20.26 | 10.92 | 16.956 | <0.001 |

| No | 725 | 39.5 | 18.21 | 9.690 | ||

| Shift work | ||||||

| Yes | 985 | 53.6 | 20.36 | 10.86 | 16.130 | <0.001 |

| No | 851 | 46.4 | 18.40 | 9.97 | ||

Notes: abTukey’s test was used for post-hoc test, and the groups marked with different letters represent the statistical differences between the two comparisons. p<0.05.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CES-D score, score of depressive symptoms.

Correlations Among Continuous Variables

Table 2 reports the correlations of SPOS score and GSES score with CES-D score. The mean scores of CES-D score, SPOS score, and GSES score were 19.45±10.50, 41.36±13.09, and 25.35±9.30 respectively. Both SPOS score and GSES score were negatively correlated with CES-D score. Also, SPOS score was positively correlated with GSES score.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Continuous Variables

| Variables | Mean | SD | CES-D Score | SPOS Score | GSES Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D score | 19.45 | 10.50 | 1 | ||

| SPOS score | 41.36 | 13.09 | −0.624** | 1 | |

| GSES score | 25.35 | 9.30 | −0.459 ** | 0.267** | 1 |

Notes: **p<0.01 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CES-D score, score of depressive symptoms; SPOS score, score of perceived organizational support; GSES score, score of self-efficacy.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression analysis results of the factors correlated with CES-D score are displayed in Table 3. In step 1, the demographic and working factors (age, gender, shift work, night shift, occupational category) explained CES-D score (F=6.484, adjusted R2=0.024, P<0.01). In step 2, SPOS score and GSES score were added and they ameliorated the model fitting of CES-D score (F=190.888, adjusted R2=0.485, ΔR2=0.461, P<0.01). SPOS score showed a significant main influence on CES-D score (β=−0.538, P<0.01), and GSES score showed a significant main influence on CES-D score (β=−0.313, P<0.01). The SPOS score×GSES score interaction term significantly explained an extra 9.7% of the variance (F=253.932, adjusted R2=0.582, ΔR2=0.097, P<0.01) in step 3. The interaction term was positively correlated with CES-D score (β=0.334, P<0.01). Simple slope analysis showed that when GSES score increases, the relationship between SPOS score and CES-D score reduces. It will be seen from this that the associations between SPOS score and CES-D score were gradually decreased in the low (1 SD below the mean, β=−0.589, P<0.01), mean (β=−0.338, P<0.01), and high (1 SD above the mean, β=−0.087, P<0.01) groups of GSES score. The interaction term is presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Results of CES-D Score

| Variables | Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.010 | −0.018 | −0.010 |

| Gender | −0.008 | −0.012 | −0.010 |

| Shift work | 0.038 | −0.014 | −0.017 |

| Night duty | −0.059* | 0.012 | −0.006 |

| Occupational category | |||

| Dummy_1 | −0.039 | −0.020 | −0.014 |

| Dummy_2 | −0.076** | −0.041* | −0.032 |

| Dummy_3 | −0.115** | −0.056** | −0.035* |

| SPOS score | −0.538** | −0.422** | |

| GSES score | −0.313** | −0.379** | |

| Interaction | 0.334** | ||

| F | 6.484** | 190.888** | 253.932** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.024 | 0.485 | 0.582 |

| ΔR2 | 0.024 | 0.461 | 0.097 |

Notes: Gender, women versus men; shift work, no versus yes; night duty, no versus yes; Dummy_1, chemical workers versus refinery workers; Dummy_2, transportation workers versus refinery workers; Dummy_3, other workers versus refinery workers. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (two-tailed).

Abbreviations: CES-D score, score of depressive symptoms; SPOS score, score of perceived organizational support; GSES score, score of self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Simple slope plot of interaction between SPOS score and GSES score on CES-D score.

Notes: Low, 1 SD below the mean; high, 1 SD above the mean.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CES-D score, score of depressive symptoms; SPOS score, score of perceived organizational support; GSES score, score of self-efficacy.

Discussion

As far as we know, this research was the first to confirm the moderating role of self-efficacy on the relationship between POS and depressive symptoms among petroleum workers in China. In this research, POS had significantly negative correlation with depressive symptoms, and self-efficacy attenuate the association between POS and depressive symptoms. We also found that 63.2% of the petroleum workers investigated in our study had depressive symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese petroleum workers was higher than underground coal miners according to previous research.38 The mean score of depressive symptoms was higher than in other Chinese occupational populations.7,39 So, it is necessary to reduce the depressive symptoms of petroleum workers in China. Among demographic and working variables, occupational category, shift work, and night duty were associated with depressive symptoms. These correlations were already discussed in previous research.40–42 Understanding the working factors of depressive symptoms is helpful to promote a comprehensive model for interventions in petroleum workers.

The study showed that POS was negatively related to depressive symptoms, which was consistent with previous research.20 We found that workers with a high level of POS are less likely to experience depressive symptoms. This may be because when their organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions, they can feel an effective sense of organizational support that causes positive work attitudes and job satisfaction, and then has positive effects on their mental health.18,19,43 Through previous research, POS was found to be able to relieve depressive symptoms in different groups.20,21 This meant that POS was a positive coping resource for depressive symptoms among petroleum workers in China. Therefore, to relieve the depressive symptoms of petroleum workers, enterprise administrators should give more organizational support to their employees.

Furthermore, our study also found that self-efficacy was negatively related to depressive symptoms and can attenuate the association between POS and depressive symptoms. It showed that if petroleum workers feel more sense of self-efficacy, they can better reduce their depressive symptoms at a lower POS level. The result was concordant with our hypothesis. This relationship between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms has been widely discussed in workers of different genders and different countries.44,45 A high sense of self-efficacy can reduce the depressive symptoms of workers. One reason for this result may be that those with higher self-efficacy have more confidence, so they have better well-being and feel more like they belong.46 This showed that the belief in one’s competence to cope with a broad range of stressful or challenging demands is considered one of the most important coping resources for overcoming depressive symptoms of petroleum workers in China. According to our study, we can reduce depressive symptoms by improving self-efficacy of petroleum workers in China.

Therefore, we can improve POS or self-efficacy to alleviate depressive symptoms of petroleum workers. Petrochemical enterprises should ensure the fairness of salary, welfare, reward, and promotion of petroleum workers, pay attention to their emotional needs, provide help in case of difficulties, respect and value their contributions, provide training opportunities for them, and provide necessary information and material assistance for work. Previous studies have shown that these measures can improve the POS of workers.47 For improving self-efficacy, petroleum workers can regularly watch inspirational videos of successful people in the same field. They can also set a timer to stand and stretch several times a day, and adding 1 km to the total run distance each week is available. Petrochemical enterprises should encourage petroleum workers, implement bonus policies, and hold praise conferences and so on. These measures have been proven to improve self-efficacy of workers.48,49

However, there are still several limitations to this study. Firstly, although our data meet the four conditions of linear regression – linear trend, independence, normality, homogeneity of variance – it is hard to study the causality between the variables. Therefore, longitudinal studies should be conducted to confirm these findings. Secondly, the sample in our study only includes workers in one petrochemical industry. A large sample size and better response rate can well represent the petroleum workers, which is helpful to the promotion of our research results. Thirdly, the correlation between research variables may be influenced by the results of self-administered questionnaires. Although, we have taken many effective process control measures to reduce common methodological deviations, including using highly reliable and effective measurement tools, establishing measurement intervals between independent variables and dependent variables, guaranteeing anonymity of respondents, and ensuring the accuracy of the answers.

Conclusion

POS and self-efficacy were negatively correlated with depressive symptoms. Self-efficacy can weaken the relationship between POS and depressive symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese petroleum workers is high. In the prevention and treatment of depressive symptoms among petroleum workers, besides providing enough POS, self-efficacy intervention should also be considered.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was in accordance with the ethical standards, and was approved by the Committee on Human Experimentation of China Medical University.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all petroleum workers.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A, et al. Combined healthy lifestyle is inversely associated with psychological disorders among adults. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd, Bruce. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope, World Health Organization. Long Range Planning. 2002;35(5):558. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niedhammer I, David S, Degioanni S. Association between workplace bullying and depressive symptoms in the French working population. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fushimi M, Saito S, Shimizu T. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and related factors in Japanese employees as measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Community Ment Hlt J. 2013;49(2):236–242. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9542-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okechukwu CA, Ayadi AME, Tamers SL, et al. Household food insufficiency, financial strain, work-family spillover, and depressive symptoms in the working class: the work, family, and health network study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):126–133. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chunli D. More than half of occupational population are in a state of depression in China. Saf Health. 2012;1:34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai J, Yu H, Wu J, et al. Analysis on the association between job stress factors and depression symptoms. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2010;39(3):342–34. PMID: 20568467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler DA, McLaughlin TJ, Rogers WH, et al. Job performance deficits due to depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1569–1576. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:398–412. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. Unemployment, job retention, and productivity loss among employees with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1371–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao W-W, Xu D-D, Cao X-L, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu G, Yu S, Wu H, et al. The effect of occupational stress on depression symptoms among 244 policemen in a city. Chi J Prev Med. 2015;49(10):924–929.PMID: 26813728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen WQ, Wong TW, Yu TS. Mental health issues in Chinese offshore oil workers. Occup Med. 2009;59(8):545–549. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen MB, Tvedt SD, Matthiesen SB. Prevalence and occupational predictors of psychological distress in the offshore petroleum industry: a prospective study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(8):875–885. doi: 10.1007/s00420-012-0825-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Netterstr B, Conrad MN, Bech P, et al. The relationship between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):118–132. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, et al. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtessis JN, Eisenberger R, Ford MT, et al. Perceived organizational support: a meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory (article). J Manage. 2017;43(6):1854–1884. doi: 10.1177/0149206315575554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright PJ, Kim PY, Wilk JE, et al. The effects of mental health symptoms and organizational climate on intent to leave the military among combat veterans. Mil. Med. 2012;177:773–779. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu L, Hu S, Wang L, et al. Positive resources for combating depressive symptoms among Chinese male correctional officers: perceived organizational support and psychological capital. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma L, Hu S, Wang L. Study on relationship between effort-reward imbalance and depressive tendency among prison policemen: the mediation role of perceived organizational support. Pract Prevent Med. 2013;20:41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–457. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pu J, Hou HP, Ma RY. Direct and indirect effects of self-efficacy on depression: the mediating role of dispositional optimism. Curr Psychol. 2017;36(3):410–416. doi: 10.1007/s12144-016-9429-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sympa P, Vlachou E, Kazakos K, et al. Depression and self-efficacy in patients with type 2 diabetes in Northern Greece. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2018;18(4):371–378. doi: 10.2174/1871530317666171120154002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh Y-H, Wang H-H, Ma S-C. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between workplace bullying, mental health and an intention to leave among nurses in Taiwan. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2019;32(2):245–254. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang L, Liang Y-L, Hou -J-J, et al. General self-efficacy mediates the effect of family socioeconomic status on critical thinking in Chinese medical students. Front Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Z, Hua W, Wenquan T, et al. Moderating effect of self-efficacy on sense of security and depression among the armed soldier population. J Guiyang Med Coll. 2012;37(4):369–375. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makara-Studzińnska M, Golonka K, Izydorczyk B Self-efficacy as a moderator between stress and professional burnout in firefighters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16020183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prati G, Pietrantoni L, Cicognani E. Self-efficacy moderates the relationship between stress appraisal and quality of life among rescue workers. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2010;23(4):463–470. doi: 10.1080/10615800903431699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu XC, Tang MQ. The comparison of SDS and CES-D on college students’ depressive symptoms. Chin Ment Health J. 1995;9:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Chang Y, Fu J, et al. The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang ZY, Liu L, Shi M, Wang L. Exploring correlations between positive psychological resources and symptoms of psychological distress among hematological cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Psychology Health Med. 2016;21(5):571–582. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1127396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang YL, Liu L, Wang XX, et al. Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu J, Sun W, Wang Y, et al. Improving job satisfaction of Chinese doctors: the positive effects of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. Public Health. 2013;127(10):946–951. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolin JH.Hayes, Andrew F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: the Guilford Press.J EDUC MEAS 2014;51(3):335–337. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L, Wang L, Chen J. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among chinese underground coal miners. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:987305. doi: 10.1155/2014/987305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu L, Pang R, Sun W, et al. Functional social support, psychological capital, and depressive and anxiety symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS employed full-time. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:324. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavičić Žeželj S, Cvijanović Peloza O, Mika F, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms among gas and oil industry workers. Occup Med. 2019;69(1):22–27. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqy170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ljosa CH, Tyssen R, Lau B. Mental distress among shift workers in Norwegian offshore petroleum industry–relative influence of individual and psychosocial work factors. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(6):551–555. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthelsen M, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, et al. Shift schedules, work factors, and mental health among onshore and offshore workers in the Norwegian petroleum industry. Ind Health. 2015;53(3):280–292. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2014-0186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zumrah AR, Boyle S. The effects of perceived organizational support and job satisfaction on transfer of training. Personnel Rev. 2015;44(2):236–254. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2013-0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taneichi H, Asakura M, Sairenchi T, et al. Low self-efficacy is a risk factor for depression among male Japanese workers: a cohort study. Ind Health. 2013;51(4):452–458. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2013-0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hwang W, Kim J, Rankin S. Depressive symptom and related factors: a cross-sectional study of korean female workers working at traditional markets. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1465. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salles A. Self-efficacy as a measure of confidence. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(5):506. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu L. Fuzzy comprehensive model for evaluating degree of perceived organizational support of staffs. J Univ Shanghai Sci Technol. 2013;35(1):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buckworth J. Promoting self-efficacy for healthy behaviors. ACSMs Health Fit J. 2017;21(5):40–42. doi: 10.1249/FIT.0000000000000318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bingöl TY, Batik MV, Hosoglu R, Firinci KA. Psychological resilience and positivity as predictors of self-efficacy. Asian J Educ Training. 2019;5(1):63–69. doi: 10.20448/journal.522.2019.51.63.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]