Abstract

Objectives:

Ethnoracial disparities in sleep health across the lifecourse may underlie other disparities in health and well-being among adults in the United States. We evaluated if socioenvironmental stressors, which likely differ by the race/ethnicity of college students, may contribute to sleep disparities in this demographic group.

Design/Measurements:

National Health Interview Survey data pooled from 2004-2017 were used to test the hypothesis that ethnoracial disparities in sleep exist among college students residing in dormitories in the US.

Setting:

Nationally-representative survey data.

Participants:

2,119 college students residing in dormitories (71% White; 16% Black/African-American; 7% Hispanic/Latino; 6% Asian).

Results:

The prevalence of short sleep duration was higher among Black/African-American compared to White students, but not among Hispanics/Latinos and Asians, after adjusting for age, gender, region of residence. In fully-adjusted models, Black/African-Americans, while no longer statistically significant after adjustments, were more likely to report short sleep duration compared to White students (adjusted prevalence ratio; [aPR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.98-1.71]). The prevalence of separate insomnia symptoms did not differ by ethnoracial group in adjusted models. Only Asian students had a higher prevalence (aPR = 1.40, 95% CI:1.12-1.75) of non-restorative sleep compared to Whites.

Conclusion:

Black/African-American but not Hispanic/Latino or Asian college students were more likely than Whites to report short sleep duration. Insomnia symptoms did not differ between groups, while Asians experienced more non-restorative sleep. Future studies should investigate the socioenvironmental causes of disparities using longitudinal designs, larger sample sizes, better SES indicators, and objective sleep measures.

Keywords: College students, sleep, sleep health, disparities, ethnoracial

Introduction

Sleep is a complex physiological and behavioral process that is important for both physical and mental health. Optimal sleep duration, currently operationalized in consensus recommendations for adults as obtaining ≥7 hours of sleep on a regular basis, may contribute to racial/ ethnic health disparities.1,2 Work, school, social, and other intrapersonal activities impose constraints on time.3 Various types of mandatory activities like scheduled school or work may structurally contribute to ethnoracial differences in sleep.4,5 Whitehead defines differences in health that are avoidable, modifiable, and inequitable in nature as disparities6, and disparities in sleep health have been observed. For instance, a meta-analysis of data collected from over 3,156 White and 1,010 Black/African-American (hereafter, Black) adults found disparities in duration of sleep, the amount of time in bed spent sleeping, and the percentage of time spent in deeper stages of sleep, with Blacks having a lower likelihood of meeting criteria for optimal sleep health on multiple indices.7 Race and ethnicity are associated with dimensions of sleep health beyond sleep duration. These additional dimensions of sleep health include the higher prevalence of polysomnographically-measured sleep disordered breathing among Hispanic/Latino Americans, reports of poorer overall sleep quality among Chinese Americans,8 and among Blacks, shorter time in bed, and lower sleep efficiency.9

Obligations associated with life as a college student may disrupt circadian phase, contributing to irregular sleep patterns10 and hindering regulation of neural systems that underlie cognitive function.11 Some studies suggest that college students may forgo sleep, engage in alcohol and stimulant use,11 and experience poor sleep quality.12 The competing demands to complete coursework, study, and potentially maintain employment while allowing time for leisure may also serve as structural barriers to healthful sleep. Importantly, strategies commonly employed by college students such as “pulling all-nighters” to meet academic success may prevent adherence to recommended sleep behaviors and, ultimately, prove counterproductive to this goal.11 For example, in a sample of participants aged 18 to 25 years old, 30 hours of acute sleep deprivation decreased performance on a visual discrimination task, a test of the extent to which test-takers are able to organize and interpret information. Performance decrements following an all-nighter of sleep deprivation persisted even after two subsequent nights of recovery sleep.13 These findings warrant further exploration of sleep health among college students.

Epidemiologic investigations identify college students as a population at risk for insufficient sleep. A greater proportion of college students (50-60%) report weekday sleepiness compared to the general population and may engage in deleterious behaviors exacerbated by insufficient sleep, including driving while fatigued, and/or under the influence of alcohol.14-17 Academic performance is also negatively impacted by the insufficiency of sleep.9,11

Little extant literature has focused on sleep disparities due to racial and/or ethnic identity during the transition into young adulthood. Suboptimal sleep health among college students could hinder success in higher education and beyond as behaviors or coping strategies for time demands may persist further into adulthood. Furthermore, social determinants of sleep health across racial and ethnic groups in college have been relatively understudied, especially in large, nationally-representative samples. In a sample of 4714 former college students, shorter sleep duration among African-Americans, but not Whites or Asians, was associated with greater student loan burden and related debt.18 Sleep health disparities at this life stage may contribute to educational and health disparities. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to characterize ethnoracial disparities in sleep health in a nationally representative sample of US college-aged adults living in college dormitories. Specifically, we examined self-reported habitual sleep duration, insomnia symptoms (difficulties falling asleep and staying asleep), and nonrestorative sleep.

Methods

National Health Interview Survey

Data included in this analysis was collected in years 2004-2017 of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm).19 The NHIS collects self-reported data among individuals and their households across a broad selection of health conditions, including health behaviors and other health-related information, from non-institutionalized members of the US population. Households are sampled continuously over the course of the survey year. A multi-stage sampling methodology is employed to promote representativeness of the nation. To ensure quality, data are obtained by using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in which trained interviewers from the US Census Bureau elicit and enter data directly into the computer during the in-person home visit. The unconditional sample adult module response rate was 62% across the years studied (range 53%-72%).

From 2004 to 2017, 2,550 NHIS participants reported living in a college dormitory. Those who reported attaining less than a high school education (n=8) or were missing racial/ethnic data (n=64) were excluded. Due to small sample size, those identifying as “American Indian/Alaskan Native” (n=9) were not included in the final analytic sample. Participants were excluded if they had missing data for sleep duration (n=222), sleep data was not ascertained (n=36), sleep duration was unknown (n=4), or sleep duration was biologically implausible (≤2 hours of sleep/night; n=1). Participants over the age of 25 (n=87) were also excluded. The final sample consisted of 2,119 participants.

Assessment of Race/Ethnicity

Racial identification included response categories “White”, “Black/African-American”, “American Indian/Alaskan Native”, or “Asian”. Ethnic identification consisted of “Hispanic/Latino” or “Non-Hispanic/Latino”. We included Non-Hispanic Whites (hereafter, Whites), Non-Hispanic Blacks (hereafter, Blacks), Non-Hispanic Asians (hereafter, Asians), and Hispanics/Latinos in this analysis.

Assessment of Multiple Sleep Dimensions

Sleep Duration.

Participants’ estimates of overall time spent in sleep were assessed with the question “On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period?” with integer response categories or “Refused” or “Don’t know”. Interviewers were instructed to report hours of sleep in whole numbers, rounding values of 30 minutes or more up to the nearest hour and rounding values less than 30 minutes down to the nearest hour. Sleep duration was categorized as <7 hours, 7-8 hours, and >8 hours. Responses were recorded on a scale of 0-24 (integer values). Sleep duration was assessed in all participants between survey years 2004 and 2017 (n=2,119).

Trouble Staying Asleep.

Participants were asked, “In the past week, how many times did you have trouble falling asleep?” Responses were recorded on a scale of 0-7 (integer values). Scale values ranged from 0 to “6 times” and “7 or more times”. Other possible responses included “Unknown” and “Refused”. All sleep quality measurements were assessed among all participants between survey years 2013 and 2017 (n=1,174).

Non-restorative sleep.

Participants responded to, “In the past week, on how many days did you wake up feeling well rested?” Possible responses ranged from 0 to 7 or more days. Failure to obtain restful sleep was defined as waking unrested 4 or more days per week.

Trouble Falling Asleep.

Difficulty falling asleep was assessed through the question “In the past week, how many times did you have trouble falling asleep?” Responses were coded on a scale ranging from 0 to “6 times” and “7 or more times”. Alternative responses included “Unknown” and “Refused”.

Insomnia Symptoms.

A composite variable was calculated by summing numeric responses to the Trouble Falling Asleep and Trouble Staying Asleep items. Composite scores greater than three were considered indicative of sleep disturbances.

Potential confounders

Sex/gender.

Responses were categorized as “Male” or “Female”. Other possible responses included “Refused”, “Not Ascertained”, and “Don’t Know”.

Education Attainment.

Level of educational attainment was assessed with the question, “What is the highest level of school you have completed, or the highest degree you have received?” Only participants indicating having attained “Completed high school”, “some college” (defined as 1 to 4 years of college, 1 to 3 years of college, 1 to 2 years of college, or 3 to 4 years of college) or “College graduate or post-graduate” (defined as 4 years of college or Bachelor’s degree, or 5+ years of college) were included in the analysis.

Annual Household Income.

Annual pre-tax income was assessed with the question, “What is your best estimate of your total income/ the total income of all family members from all sources, before taxes, in 2016?” participants could have reported their parents’ income or only their own personal income if they were not, for instance, dependents. Annual household income was adjusted for in our statistical models despite the lack of clarity regarding how participants interpreted and answered the question. Responses were grouped into ranges between $0 and $100,000 and above.

Employment Status.

Participants provided self-reported work status. Possible responses ranged “Working for pay at job” and “Working without pay at job”, to “Unemployed: Have job to return to”, and “Not in labor force”. Responses were categorized according to content as “Employed”, “Employed without pay”, “Unemployed”, or “Not in labor force”.

Body Mass Index (BMI).

Body-Mass Index was based on the participant’s self-reported height and weight, which was calculated as height/weight (kg/m2).

Poverty.

Participants’ poverty status was assessed relative to current federal poverty levels for the survey year with the question “Was your total family income from all sources <250% of the poverty threshold or ≥250% of the poverty threshold?” Possible answers included “Less than”, “More than”, “Unknown”.

Region of Residence.

Residential location was categorized as “Northeast”, “North Central/Midwest”, “South”, “West”, or “Unknown”.

Smoking Status.

Current and lifetime smoking status were analyzed as “Never smoked”, “Current Smoker” (every day or some day smoker), and “Former Smoker”.

Alcohol consumption.

Current and lifetime alcohol consumption were analyzed as “Never drank” (0 drinks in lifetime), “Former drinker” (1+ drinks in lifetime but no drinks in past year), “Current Drinker” (1+ drink in the past year).

Physical Activity.

Moderate and vigorous physical activity were assessed with the question “How often do you do light or moderate/vigorous leisure-time physical activities for at least 10 minutes that cause only light/heavy sweating or a slight-to-moderate/large increase in breathing rate or heart rate?” Responses included two-digit numbers ranging from 0-30. Other possible responses included “Less than once per week”, “Never”, “Unable to do this type of activity”, “Refused”, “Not Ascertained” or “Don’t Know”. In accordance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines for physical activity, numerical responses were grouped into two categories: low physical activity (<15 times per week) and high physical activity (>15 times per week).

Self-reported General Health Status.

Participants’ perceptions of overall health were assessed with “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Other possible responses include “Refused” and “Don’t know”. Responses “Excellent” and “Very good” were combined to comprise an Excellent/Very good variable. Similarly, responses of “Fair” or “Poor” were combined into a Fair/Poor variable.

Statistical Analysis

Fourteen years (2004-2017) of NHIS survey data were pooled and merged by the Integrated Health Interview Series.20 While sleep duration data were available from 2004-2017, insomnia symptoms and non-restorative sleep were only measured from 2013-2017. For all analyses, we used sampling weights that account for the unequal probabilities of selection resulting from the sample design, nonresponse, and oversampling of certain subgroups (e.g., elderly, racial/ethnic minorities). Standard errors or variance estimates were calculated by using Taylor series linearization.21 Stata, version 15, software (StataCorp. LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses. Categorical variables are presented using raw (unweighted) frequencies accompanied by the corresponding weighted percentages.

Using separate Poisson regression models with robust variance, we estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) for short sleep duration, difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and perception of restorative sleep among Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian college students compared to their White counterparts.22 Models were adjusted for sex/gender, employment status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, self-reported health status, and region of residence. In a secondary analysis, we combined insomnia symptoms (difficulty falling asleep and difficulty staying asleep).

Results

Study Population Characteristics

Sociodemographic and sleep characteristics are presented in Table 1. The study population of 2,119 participants consisted of Whites (71%), Blacks (16%), Hispanics/Latinos (7%), and Asians (6%). Sixty-five percent of the sample reported unemployment. Among the employed 35%, self-reported occupational class included support services (59%), laborers (34%), and professional/ management positions (7%). Almost all (99%) participants reported income of <$35,000 per year, and 91% reported an income <100% Federal Poverty Line. Students most frequently reported geographical residence in the Midwest United States (32%), followed by the South (29%), Northeast (28%), and Western (11%) regions.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of College Students by Race, 2004-2017, National Health Interview Survey (N=2,119)

| White | Black/ African American |

Hispanic/Latino | Asian | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sample size | 1,424 | 71 | 340 | 16 | 173 | 7 | 182 | 6 | 2,119 | 100 |

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Age | 19.5 | 0.09 | 19.6 | 0.08 | 19.5 | 0.17 | 19.9 | 0.22 | 19.6 | 0.08 |

| Sociodemographics | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Female | 752 | 50 | 206 | 56 | 91 | 51 | 85 | 44 | 1,134 | 51 |

| Male | 672 | 50 | 134 | 44 | 82 | 49 | 97 | 56 | 985 | 49 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||||

| High school graduate | 257 | 18 | 66 | 22 | 29 | 18 | 26 | 19 | 378 | 19 |

| Some college | 1,145 | 80 | 268 | 76 | 137 | 78 | 126 | 69 | 1,676 | 79 |

| ≥ College | 22 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 30 | 12 | 65 | 2 |

| Unemployed (not in workforce) (yes) | 877 | 64 | 229 | 64 | 104 | 59 | 142 | 79 | 1,352 | 65 |

| Annual household income (<$35,000 per year) | 1,387 | 99 | 325 | 99 | 170 | 98 | 168 | 96 | 2,050 | 99 |

| Living in poverty (<100% Federal Poverty Level) | 1,231 | 92 | 288 | 91 | 152 | 92 | 147 | 88 | 1,818 | 91 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||

| Professional/management | 89 | 7 | 18 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 128 | 7 |

| Support Services | 730 | 57 | 176 | 67 | 72 | 55 | 79 | 71 | 1,057 | 59 |

| Laborers | 416 | 36 | 66 | 25 | 49 | 35 | 28 | 22 | 559 | 34 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 360 | 28 | 47 | 17 | 52 | 36 | 67 | 44 | 526 | 28 |

| Midwest | 551 | 39 | 47 | 14 | 36 | 22 | 19 | 10 | 653 | 32 |

| South | 304 | 20 | 241 | 68 | 48 | 23 | 69 | 33 | 662 | 29 |

| West | 209 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 37 | 18 | 27 | 13 | 278 | 11 |

| Sleep duration | ||||||||||

| <7 hours | 361 | 26 | 150 | 41 | 54 | 29 | 53 | 30 | 618 | 29 |

| 7-8 hours | 952 | 66 | 168 | 52 | 114 | 68 | 118 | 62 | 1,352 | 64 |

| >8 hours | 111 | 8 | 22 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 149 | 7 |

| Trouble falling asleep (≥3 days/week) | 145 | 18 | 39 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 222 | 19 |

| Trouble staying asleep (≥3 days/week) | 69 | 9 | 28 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 116 | 10 |

| Woke up feeling unrested most days (≥4 days/week) | 312 | 38 | 87 | 46 | 51 | 43 | 49 | 45 | 499 | 41 |

| Sleep medication (≥3 days/week) | 34 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 38 | 3 |

| Trouble falling & trouble staying asleep | 167 | 22 | 47 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 257 | 22 |

| Trouble falling & trouble staying asleep & not waking up rested | 370 | 46 | 95 | 50 | 55 | 47 | 53 | 48 | 573 | 47 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Never | 1,342 | 94 | 334 | 98 | 161 | 93 | 176 | 97 | 2,013 | 95 |

| Former | 20 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 31 | 1 |

| Current | 62 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 75 | 4 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||

| Never | 488 | 32 | 158 | 46 | 63 | 32 | 81 | 47 | 790 | 35 |

| Current | 911 | 67 | 171 | 52 | 108 | 67 | 99 | 52 | 1,289 | 64 |

| Former | 18 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Leisure-time physical activity | ||||||||||

| Never/unable | 110 | 8 | 51 | 14 | 28 | 17 | 30 | 19 | 219 | 10 |

| Low | 443 | 33 | 125 | 39 | 54 | 29 | 62 | 33 | 684 | 34 |

| High | 866 | 59 | 162 | 47 | 91 | 54 | 90 | 48 | 1,209 | 56 |

| Cardiometabolic health outcomes | ||||||||||

| Overweight a | 309 | 24 | 97 | 38 | 49 | 33 | 32 | 23 | 487 | 27 |

| Obesity b | 131 | 13 | 61 | 28 | 19 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 220 | 15 |

| Health status | ||||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 1,228 | 87 | 264 | 77 | 145 | 83 | 144 | 80 | 1,781 | 85 |

| Good | 168 | 11 | 56 | 19 | 23 | 13 | 33 | 17 | 280 | 13 |

| Fair/poor | 28 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 58 | 2 |

Overweight defined as body mass index (BMI) calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2), value of 25-<30 kg/m2

Obese defined as BMI value of 30 or higher

Although most (95%) participants reported never smoking, 1% reported being former smokers, and 4% were current smokers. Thirty-five percent of participants reported never having consumed alcohol, whereas 1% reported having ever consumed alcohol in their lifetime but not regularly, and 64% reported regularly consuming alcohol at the time of interview. Fifty-six percent of the sample reported high physical activity, whereas 34% indicated low physical activity, and 10% engaging in no physical activity by either choice or inability.

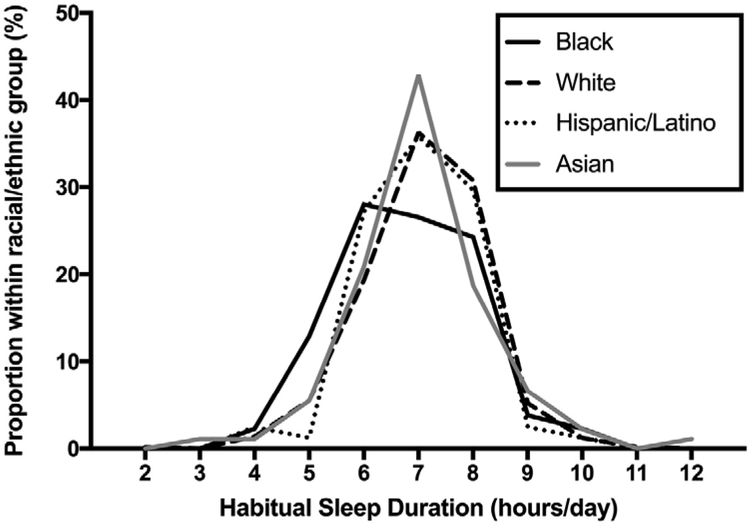

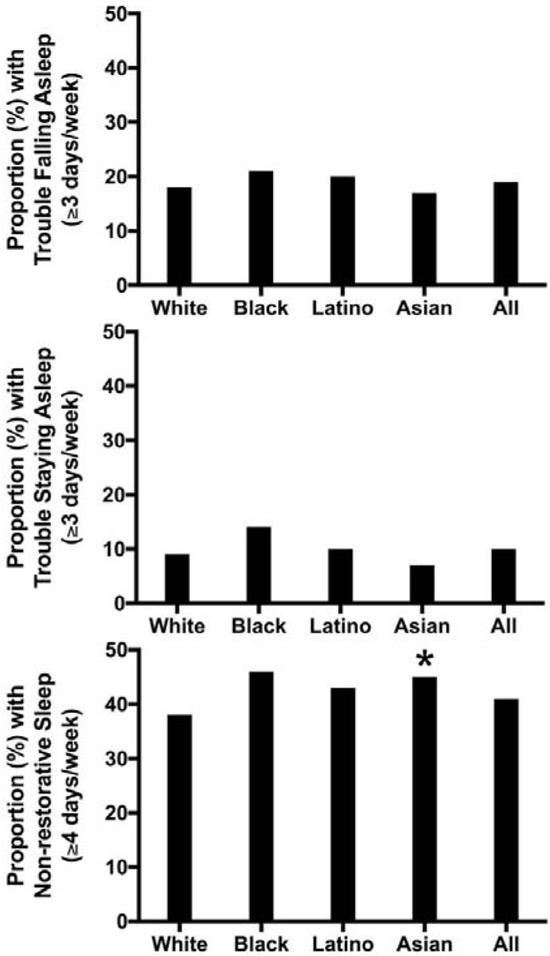

Of the total sample, 29% of students reported short sleep (<7 hours). Sixty-four percent of students reported obtaining 7-8 hours of sleep while 7% percent reported longer sleep (>8 hours). Twenty-two percent of students endorsed symptoms of chronic insomnia, defined as three or more instances of trouble falling or staying asleep within the past week, while 41% indicated experiencing non-restorative sleep. The distribution of mean sleep durations by racial and ethnic group are illustrated in Figure 1, and Figure 2 shows the prevalence of insomnia symptoms and sleep quality by race/ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Proportions of self-reported sleep duration by ethnoracial group in US college students (NHIS 2004-2017).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of insomnia symptoms and sleep quality among college students living in dormitories by ethnoracial group. Top panel: percentages of students self-reporting three or more nights of difficulty falling asleep by race and ethnicity. Middle panel: percentages of students reporting three or more nights of difficulty staying asleep by race and ethnicity. Bottom panel: percentages of students self-reporting three or more nights of experiencing restful sleep by race and ethnicity. For all panels, * denotes p <.05 compared to Whites.

Sleep among Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian College Students compared to White Counterparts

In minimally-adjusted models, comparisons of self-reported sleep characteristics across White, Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian ethnoracial groups revealed Blacks have shorter sleep duration than Whites (aPRBlacks = 1.35, 95% CI= 1.08-1.69). However, adjustment for sociodemographic and health behavior variables attenuated these associations (all ps > .05). See Table 2 for the distribution of sleep duration by ethnoracial group. The prevalence of short sleep among White students was 26% compared to 41% among Blacks, 30% Asian, and 29% Hispanic/Latino. Due to small sample sizes, prevalence ratios were not estimable for comparisons between ethnoracial minority groups and Whites regarding prevalence of long sleep (7–9 hours of sleep per night). No ethnoracial group reported more or less frequent symptoms of insomnia than Whites. In fully-adjusted models, Asians reported greater non-restorative sleep compared to Whites (aPR Asians=1.40, 95% CI=1.12-1.75; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence Ratios of Sleep Characteristics among Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian College Students Living in a Dormitory compared to White College Students, National Health Interview Survey, 2004-2017, (N=2,119)

| Blacks/African-Americans compared to Whites |

Hispanics/Latinos compared to Whites | Asians compared to Whites |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Sleep duration | |||||||||

| <7 hours vs. 7-8 hours |

1.36 (1.04-1.78) |

1.30 (0.99-1.69) |

1.30 (0.98-1.71) |

1.05 (0.80-1.37) |

1.01 (0.76-1.34) |

1.03 (0.76-1.39) |

1.06 (0.70-1.61) |

1.20 (0.82-1.76) |

1.24 (0.84-1.84) |

| ≥9 hours vs. 7-8 hours | 1.24 (0.72-2.13) |

NE* | NE* |

0.34 (0.13-0.90) |

NE* | NE* | 0.99 (0.45-2.18) |

NE* | NE* |

| Trouble falling asleep (≥3 days/week)a | 0.99 (0.73-1.36) |

0.95 (0.69-1.29) |

0.96 (0.70-1.31) |

1.10 (0.74-1.64) |

1.15 (0.78-1.71) |

1.20 (0.82-1.74) |

0.95 (0.59-1.54) |

1.06 (0.61-1.83) |

1.11 (0.66-1.88) |

| Trouble staying asleep (≥3 days/week)a | 1.18 (0.74-1.89) |

1.07 (0.63-1.82) |

1.04 (0.61-1.79) |

1.03 (0.50-2.14) |

1.05 (0.51-2.16) |

1.09 (0.54-2.20) |

0.75 (0.35-1.63) |

0.79 (0.31-1.99) |

0.72 (0.31-1.68) |

| Woke up feeling unrested most days (≥4 days/week)a | 1.15 (0.96-1.39) |

1.14 (0.92-1.40) |

1.15 (0.93-1.42) |

1.14 (0.87-1.48) |

1.13 (0.85-1.49) |

1.16 (0.88-1.52) |

1.21 (0.97-1.50) |

1.35 (1.08-1.69) |

1.40 (1.12-1.75) |

| Sleep medication (≥3 days/week)a | 0.25 (0.05-1.19) |

NE* | NE* | 0.38 (0.05-2.66) |

NE* | NE* | 0.34 (0.04-2.53) |

NE* | NE* |

| Trouble falling asleep or staying asleepa | 0.98 (0.72-1.35) |

0.92 (0.68-1.26) |

0.93 (0.67-1.27) |

1.04 (0.71-1.52) |

1.04 (0.72-1.51) |

1.07 (0.74-1.54) |

0.89 (0.54-1.45) |

1.00 (0.58-1.73) |

0.98 (0.57-1.68) |

| Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, /and/or not waking up resteda | 1.04 (0.88-1.23) |

1.01 (0.84-1.22) |

1.01 (0.84-1.23) |

1.02 (0.80-1.32) |

1.02 (0.79-1.33) |

1.04 (0.81-1.35) |

1.06 (0.88-1.29) |

1.17 (0.95-1.43) |

1.17 (0.96-1.44) |

Model-1 adjusted for age, gender, and region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West).

Model-2 adjusted for age, gender, employment status (yes vs. no), BMI (normal, overweight, obese), smoking status (current, former, never), alcohol use status (current, former, never), physical activity (never, low, high), general health status (excellent, very good, good vs. fair/poor) and region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West).

Model-3 adjusted for age gender, employment status (yes vs. no), BMI (normal, overweight, obese), smoking status (current, former, never), alcohol use status (current, former, never), physical activity (never, low, high), general health status (excellent, very good, good vs. fair/poor), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and living in poverty; <100% Federal Poverty Level (yes vs. no).

Note. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design.

Boldface indicates statistically significant results at the 0.05 level.

Survey years: 2013-2017; sample size from 2013-2017, n=1,174

NE=Not estimable

Discussion

Using a nationally-representative sample of US college students living in dormitories, we quantified ethnoracial disparities in self-reported sleep duration and sleep quality. Compared to 26% of Whites, the prevalence of short sleep among Black students was 41%, 29% among Hispanic/Latino students, and 30% among Asian students. In minimally-adjusted models, Black students were the most likely to report short sleep duration (< 7 hours; 7-8 hours is the current recommended amount for adults23) out of all racial and ethnic groups represented in the sample. Hispanic/Latino and Asian students did not differ from Whites in their self-reported sleep duration. After adjusting for the influence of several sociodemographic, health behavior, and clinical characteristics, the association among Black students being more likely than White students to report short sleep duration was no longer statistically significant. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed. Furthermore, the inclusion of some characteristics (e.g., by including self-reported ‘general health status,’ poverty status) in our models could be considered overcontrolling as they may contribute to the apparent disparities. The minimally-adjusted results are similar to other studies of US adults that observe disparities in sleep duration by racial and ethnic group.24-26 Reports of insomnia symptoms and sleep medication use had a low prevalence, and did not significantly differ by ethnoracial group. Additionally, in this sample, Asian students were more likely than Whites to report nonrestorative sleep in fully-adjusted models.

According to previous research, many pathways may contribute to disparities in sleep health across ethnoracial groups.27,28 A meta-analysis of racial identification as a source of sleep problems suggests shorter sleep duration is associated with several factors, including adiposity, age, and gender, where younger age was associated with greater racial and ethnic differences in subjective sleep duration.7 In this study, Black racial identification among young adult students (mean age of 19.6 years) was associated with shorter sleep duration in models adjusting for age, sex/gender, and region of residence but not after additional adjustment for health behaviors, clinical characteristics, and living in poverty. While the magnitude of the association was similar as the minimally-adjusted model, future studies with greater power or larger sample sizes are warranted. Systematic differences in sleep environments – both physical and social – across racial/ethnic groups may propagate disparities in sleep health. Future research studies seeking to replicate our findings are needed, and investigations of determinants, mediators, and consequences of the observed relationships between ethnoracial groups and poor sleep among college students are warranted.

Differential exposure to psychosocial and socioemotional stressors by ethnoracial group membership likely contribute to disparities in sleep health.27 Greater prevalence of exposure to adversity may contribute to racial and ethnic differences in sleep health.29 At later life stages, discrimination attributable to ethnoracial group membership (or racism at institutional, personally mediated, and internalized levels) may be a particularly salient source of stress impacting sleep.27 Although sparsely available in this age group, other studies have examined racial discrimination as a source30 or mediator31 of disparities in sleep quality and behavioral hygiene among Blacks. Furthermore, data derived from laboratory-based polysomnographic recordings have suggested greater experience with discrimination contributes to racial/ethnic disparities in the attainment of deeper sleep, where slow-wave sleep, a sleep stage important for physiological health, was lower in Blacks. The relationship between racial identification and spending a larger proportion of overall sleep time in less deep stages of sleep was partially mediated by greater prior experiences of racial discrimination.32 Linked to elevated stress among adolescents,33 discriminatory content originating from online media may degrade sleep health among young adults.

Comparable psychosocial mechanisms may work to degrade sleep health among minority American college students. Impostor syndrome, wherein the person consistently internalizes fear related to being exposed as fraudulent or undeserving and, therefore, misattributes or discounts past achievements in the domain of interest, such as work or school.34 This syndrome, experienced across all racial/ethnic groups, has been associated with higher levels of psychological distress among Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian college students studying at US institutions.35 Elevated stress attributable to impostor syndrome may affect both quality and duration of sleep disproportionately among ethnoracial minority groups, and future research is warranted.

Other studies have found differential treatment of Asians attributable to ethnoracial group membership on college campuses.36,37 In a sample of college students, Asian ethnoracial group membership was found to moderate the relationship between subjective social status and poor sleep quality.38 Analysis in a nationally representative US sample revealed that Asian-American adults reported the fewest sleep complaints (trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, or sleeping too much) compared to other US ethnoracial groups.39 Our contradictory finding, that Asian college students reported greater levels of non-restorative sleep when compared with Whites, may result from different population sociodemographic and health behavior characteristics among these cohorts. Patterns in sleep health among college students may also differ from those of the general US adult population. More extensive investigations of sleep problems among Asian college students should be conducted.

Results from minimally-adjusted models, which show short sleep duration in the absence of sleep complaints among Black college students, may mirror larger trends in the sleep of Blacks as a whole, with Blacks reporting fewer sleep complaints.39 Short sleep duration in the absence of sleep complaints among Black college students may mirror larger trends in the general population.39 Studies using objective sleep measures have found poorer sleep among Blacks relative to members of other US racial and ethnic population groups. 8,9 “John Henryism”, defined as persistent effortful coping by expending physical and mental effort without sufficient support/resources, may underlie the association of shorter sleep duration with increasing professional responsibilities among Black adults, which contrasts with the pattern among Whites, who generally have a lower prevalence of short sleep with increasing professional responsibilities.40 John Henryism may begin earlier than in the workplace by operating in a college context to impede academic success and wellbeing among minority students. Future work is necessary to identify and evaluate if these and other factors are potential sources.

In our sample, self-reported sleep duration did not differ between Hispanic/Latino and White students. However, analyses conducted among a community sample of Hispanic/Latino men and women in the United States associate differential treatment based on ethnoracial identity with poor sleep, including shortened sleep duration among this group.41 Indeed, Hispanics/Latinos in higher education have reported unique stressors related to their ethnic minority status and treatment.42 Discrepancies between our findings and those of previous studies may stem from key differences between dorm-dwelling undergraduates and communitydwelling adults as distinct demographic populations.

Our finding that Black students obtain less sleep than their White counterparts may offer guidance for future efforts intended to address inequities in post-secondary educational attainment and related consequences for social equity,43 where postsecondary graduation rates are lowest among Blacks. Disparities in higher education attainment is complex. College grades have been linked to sleep duration, with existing analyses showing both positive and negative associations.11 Specific sleep characteristics have been linked to academic success, including sleep onset and wake times44 and sleep regularity.10 More extensive characterizations of ethnoracial differences in the sleep health of college students may illustrate discrete pathways by which sleep may affect performance, which could help tailor specific educational and behavioral interventions. Limitations of this study include cross-sectional NHIS data precluding causal inferences. Due to survey item construction, it is possible that participants reported either family or individual income. It appears that most college students reported their individual income since >90% were below the poverty level. Therefore, this measure of SES may not adequately represent the participants’ variation in household income or wealth, which could be used as resources to support healthy sleep during college. Furthermore, self-reported sleep duration could not be categorized as occurring during nocturnal sleep or napping in this dataset. Although the proportion of sample participants currently smoking was less than estimated among 18-24 year-olds in the US,45 national representativeness among our cohort ensures generalizability to the current US population. All data were self-reported, which tends to overestimate sleep duration when compared with data derived from objective measures (e.g., actigraphy and PSG) regardless of ethnoracial group membership.46 Future studies may benefit from objective measurement of sleep health dimensions (e.g., actigraphy with daily reports). Although racial discrimination may contribute to observed differences in sleep duration,27 it was not assessed in our data source. Suboptimal mental health, considered a determinant and consequence of poor health that may vary by racial/ethnic groups in college, was also unavailable.

Future investigations could compare culture-specific preferences/attitudes towards sleep and related behaviors that may encourage ethnoracial disparities in sleep duration among college students. Other studies should also consider additional factors relevant to sleep health not captured in NHIS, such as bedtime screen use47 and nightlife activities. Assessments of the physical environments (e.g., noise, lighting, air quality) of college campuses could also be evaluated. Examining these and other factors, including behaviors, common among college students and young adults may help uncover potential determinants of the observed disparities between ethnoracial group membership and sleep outcomes.

Conclusion

In this nationally-representative sample of dormitory-dwelling college students, we observed that Black students obtained less sleep than White students. However, disparities in sleep duration reported between Blacks and Whites were found to have occurred independently of differences in sleep problems, including insomnia symptoms and non-restorative sleep, and attenuated upon adjustment. There were no apparent differences in sleep duration and sleep problems among Hispanics/Latinos and compared to Whites. In addition, Asian students were less likely to report restorative sleep upon waking compared to Whites. Future studies should examine sleep insufficiency among similar, larger samples. It has been estimated that 65% of US jobs will require a post-secondary degree by 2020.48 Efforts to evaluate and improve sleep health may increase the potential benefits of pursuing higher education. Greater understandings of how sleep health may promote physical and mental health or optimize neurocognitive function may allow for students to maximize their academic potential while studying at university, thereby maximizing the potential benefits of pursuing higher education by mitigating opportunity costs.11 Future studies should seek to inform clear and actionable public health and social policy initiatives that aim to eliminate sleep disparities and achieve social, environmental, and health equity.

Acknowledgements

Support for this manuscript was provided by the Pennsylvania State University Bunton-Waller Fellowship to RJ. This work was funded, in part, by the Intramural Program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, Z1AES103325-01). The authors thank June Jiao and Lindsay Master for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Outside the current work, OMB received subcontract grants to Penn State from Mobile Sleep Technologies (NSF/STTR #1622766, NIH/NIA SBIR R43AG056250), and receives an honorarium for his role as Editor in chief (designate) of Sleep Health. Other authors report no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Curtis DS, Fuller-Rowell TE, El-Sheikh M, Carnethon MR, Ryff CD. Habitual sleep as a contributor to racial differences in cardiometabolic risk. PNAS 2017; 114: 8889–8894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandner MA, Alfonso-Miller P, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Shetty S, Shenoy S, Combs D. Sleep: Important considerations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 2016; 31: 551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritz C, Crain T. Recovery from work and employee sleep: Understanding the role of experiences and activities outside of work In: Barling J, Barnes CM, Carleton EL, Wagner DT, eds. Work and sleep: Research Insights for the Workplace. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2016: 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S, Jackson CL, Robbins R, Buxton OM. The Work-Sleep Relationship. In: Grandner M, ed. Sleep Health: Academic Press (Elsevier); 2019: In production. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson CL, Lee S, Crain T, Buxton OM. Work Experiences and Sleep In: Kawachi I, Redline S, Duncan D, eds. The Social Epidemiology of Sleep: Oxford University Press; 2019: TBD. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead M The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int 1991; 6: 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiter M, Decoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Normal sleep in African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med 2011; 12: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in sleep disturbances: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep 2015; 38: 877–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, et al. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 164: 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips AJ, Clerx WM, O’Brien CS, et al. Irregular sleep/wake patterns are associated with poorer academic performance and delayed circadian and sleep/wake timing. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershner SD, Chervin RD. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat Sci Sleep 2014; 6: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting RD, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolescent Health 2010; 46: 124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stickgold R, James L, Hobson JA. Visual discrimination learning requires sleep after training. Nat Neurosci 2000; 3: 1237–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD. Patterns and consequences of inadequate sleep in college students: Substance use and motor vehicle accidents. J Adolescent Health 2010; 46: 610–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P-Y, Chen K-L, Yang S-Y, Lin P-H. Relationship of sleep quality, smartphone dependence, and health-related behaviors in female junior college students. PloS ONE 2019; 14: e0214769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, Roane BM. Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behav Ther 2013; 44: 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker SP, Jarrett MA, Luebbe AM, Garner AA, Burns GL, Kofler MJ. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health 2018;4:174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsemann KM, Ailshire JA, Gee GC. Student loans and racial disparities in self-reported sleep duration: Evidence from a nationally representative sample of US young adults. J Epidemiol Commun H 2016;70: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Health Interview Survey. 2013. at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.)

- 20.Blewett Lynn A., Drew JAR, Griffin R, King ML, Williams KCW. IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey. 6.3 ed. Minneapolis MN: IPUMS National Health Surveys; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolters KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer; New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barros AJD, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: Methodology and Discussion. Sleep 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hale L, Do DP. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 231–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE. Short sleep duration across income, education, and race/ethnic groups: Population prevalence and growing disparities during 34 years of follow-up. Ann Epidemiol 2007; 17: 948–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillai V, Steenburg LA, Ciesla JA, Roth T, Drake CL. A seven day actigraphy-based study of rumination and sleep disturbance among young adults with depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Res 2014; 77: 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hicken MT, Lee H, Ailshire J, Burgard SA, Williams DR. “Every shut eye, ain’t sleep”: The role of racism-related vigilance in racial/ethnic disparities in sleep difficulty. Race Soc Probl 2013; 5: 100–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrov ME, Lichstein KL. Differences in sleep between black and white adults: An update and future directions. Sleep Med 2016; 18: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajeepeta S, Gelaye B, Jackson CL, Williams MA. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med 2015; 16: 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoggard LS, Hill LK. Examining how racial discrimination impacts sleep quality in African Americans: Is perseveration the answer? Behav Sleep Med 2018; 16: 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller-Rowell TE, Curtis DS, El-Sheikh M, Duke AM, Ryff CD, Zgierska AE. Racial discrimination mediates race differences in sleep problems: A longitudinal analysis. Cult Divers Ethn Min 2017; 23: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomfohr L, Pung MA, Edwards KM, Dimsdale JE. Racial differences in sleep architecture: the role of ethnic discrimination. Biol Psychol 2012; 89: 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tynes BM, Rose CA, Hiss S, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Mitchell K, Williams D. Virtual environments, online racial discrimination, and adjustment among a diverse, school-based sample of adolescents. Int J Gaming Comput Mediat Simul 2016; 6: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clance PR, Innes S. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychol Psychother-T 1978; 1: 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cokley K, McClain S, Enciso A, Martinez M. An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. J Multicult Couns D 2013; 41: 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang W-C, Goto S. The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Cult Divers Ethn Min 2008; 14: 326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park IJ, Schwartz SJ, Lee RM, Kim M, Rodriguez L. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and antisocial behaviors among Asian American college students: Testing the moderating roles of ethnic and American identity. Cult Divers Ethn Min 2013; 19: 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodin BR, McGuire L, Smith MT. Ethnicity moderates the influence of perceived social status on subjective sleep quality. Behav Sleep Med 2010; 8: 194–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Med 2010; 11: 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson CL, Redline S, Kawachi I, Williams MA, Hu FB. Racial disparities in short sleep duration by occupation and industry. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178: 1442–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alcántara C, Patel SR, Carnethon M, et al. Stress and sleep: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. SSM-Popul Health 2017; 3: 713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Von Robertson R, Bravo A, Chaney C. Racism and the experiences of Latina/o college students at a PWI (predominantly White institution). Crit Sociol 2016; 42: 715–735. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J. Racial and ethnic achievement gap trends: Reversing the progress toward equity? Educ Research 2002; 31: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trockel MT, Barnes MD, Egget DL. Health-related variables and academic performance among first-year college students: implications for sleep and other behaviors. J Am Coll Health 2000; 49: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67: 1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson CL, Patel SR, Jackson WB 2nd, Lutsey PL, Redline S. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Sleep 2018; 41: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orzech KM, Grandner MA, Roane BM, Carskadon MA. Digital media use in the 2 h before bedtime is associated with sleep variables in university students. Comput Human Behav 2016; 55: 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carnevale AP, Smith N, Strohl J. Recovery: Job growth and education requirements through 2020: Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University; 2013. [Google Scholar]