Abstract

Fused filament fabrication “3-dimensional (3-D)” printing has expanded beyond the workplace to 3-D printers and pens for use by children as toys to create objects. Emissions from two brands of toy 3-D pens and one brand of toy 3-D printer were characterized in a 0.6 m3 chamber (particle number, size, elemental composition; concentrations of individual and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC)). The effects of print parameters on these emission metrics were evaluated using mixed-effects models. Emissions data were used to model particle lung deposition and TVOC exposure potential. Geometric mean particle yields (106–1010 particles/g printed) and sizes (30–300 nm) and TVOC yields (<detectable to 590 μg TVOC/g printed) for the toys were similar to those from 3-D printers used in workplaces. Metal emissions included manganese (1.6–92.3 ng/g printed) and lead (0.13–1.2 ng/g printed). Among toys, extruder nozzle conditions (diameter, temperature) and filament (type, color, and extrusion speed) significantly influenced particle and TVOC emissions. Dose modeling indicated that emitted particles would deposit in the lung alveoli of children. Exposure modeling indicated that TVOC concentration from use of a single toy would be 1–31 μg/m3 in a classroom and 3–154 μg/m3 in a residential living room. Potential exists for inhalation of organic vapors and metal-containing particles during use of these toys. If deemed appropriate, e.g., where multiple toys are used in a poorly ventilated area or a toy is positioned near a child’s breathing zone, control technologies should be implemented to reduce emissions and exposure risk.

Keywords: 3-D printing, toys, particles, volatile organic compounds, children, exposure

Introduction

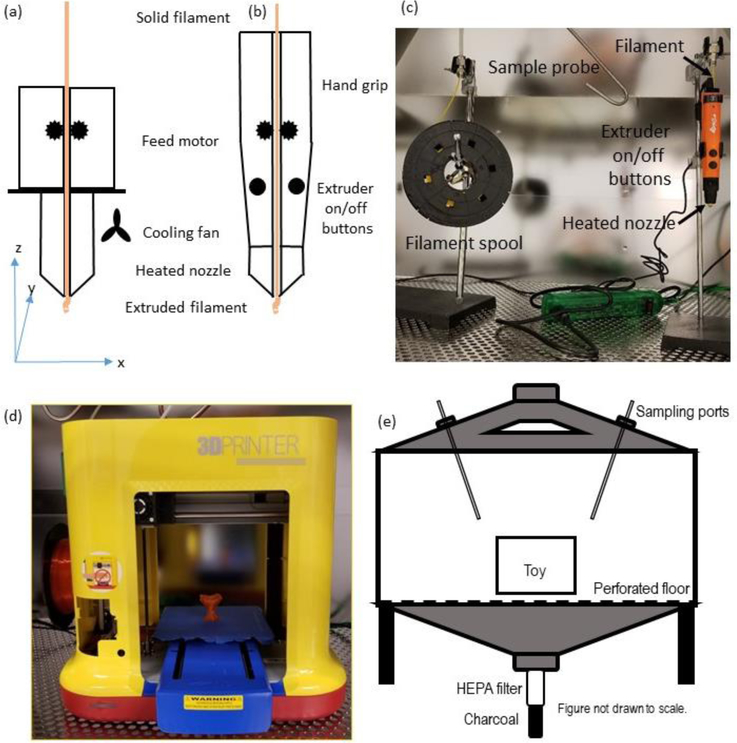

Fused filament fabrication (FFF) is a type of additive manufacturing technology that is rapidly expanding beyond industrial-scale machines used for prototyping and manufacturing to consumer markets. The availability of FFF technology to consumers includes desktop-scale “3-dimensional (3-D) printers,” smaller toy 3-D printers as well as hand-held pens for use by children to print objects. Industrial, consumer, and toy 3-D printers, and 3-D pens based on FFF technology operate on the common principle where a heated nozzle melts polymer filament to extrude it to build an object (Figure 1) (ISO/ASTM, 2015). Movement of the extruder nozzle in a toy 3-D pen is controlled manually by a child, whereas movement of the nozzle in a 3-D printer is automated. Therefore, with a 3-D pen, the distance between the extruder nozzle (emission source) and the operator is likely less than the length of the child’s arm. If a 3-D pen generates emissions, the emission source will likely be in the child’s breathing zone.

Figure 1.

Diagrams of extruders for (a) fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3-D printer and (b) toy 3-D pen. Both devices use a motor and gears to feed solid filament into a heated nozzle and extrude the melted plastic onto a surface to build a physical object. The extruder on a FFF 3-D printer is computer controlled and moves in the x, y, and z directions to build a shape. The extruder on a 3-D pen toy is hand-held and moved manually by a user to build a shape. Drawings are not to scale. (c) Photograph of experimental set-up for a toy 3-D pen. (d) Photograph of experimental set-up for a toy 3-D printer and printed rose flower stem object. (e) Schematic of experimental set-up.

Several studies have shown that industrial and desktop-scale FFF 3-D printers using polymer filaments may emit billions of particles per minute and numerous organic vapors during operation. Depending on the type of polymer and additives, particle emissions may include polymer particles (often with size below 100 nm) and/or polymer particles that contain metals, engineered nanomaterials, or surface-adsorbed chemicals (Azimi et al., 2016; Bharti et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2016; Floyd et al., 2017; Geiss et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2017; Mendes et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017; Stabile et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2017, 2018, 2019a; Stefaniak et al., 2019b; Steinle, 2016; Stephens et al., 2013; Vance et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2015; Zontek et al., 2017). Volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions also vary with the type of filament and may include styrene, methyl methacrylate, and carbonyl compounds (Azimi et al., 2016; Floyd et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2015; Mendes et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2017, 2019a, 2019b; Steinle, 2016; Vaisanen et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2017; Zontek et al., 2017). Results of these studies demonstrate that the potential for particle and vapor emissions could exist for FFF-based toy 3-D pens and printers used by children, which in turn, may lead to exposure to themselves or others when used in homes, schools, or other environments that lack appropriate control technologies to mitigate exposures to emissions. However, there is little understanding as to whether toy 3-D printers or pens emit particles and VOCs.

Reports are emerging to suggest that workplace exposure to emissions from FFF-based 3-D printers may not be without risk. For example, House et al. reported a case of work-related asthma in a worker exposed to emissions during operation of material extrusion 3-D printers using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) filament (House et al., 2017). In a survey of workers who primarily used material extrusion 3-D printers, 59% reported respiratory symptoms including nasal congestion, rhinitis, cough, and itchiness of the eyes, nose, and throat (Chan et al., 2018). In an animal toxicology study, rats who inhaled ABS emissions from a desktop-scale FFF 3-D printer developed acute hypertension after a single exposure (Stefaniak et al., 2017). It is unclear if these respiratory and cardiovascular effects are associated with inhalation of emitted particles, organic vapors, or both. However, health risks from intermittent consumer use of 3-D printers may not be the same as for workers. For example, healthy adult volunteers exposed to emissions from a 3-D printer using ABS or polylactic acid (PLA) filaments for one hour had no acute effect on inflammatory markers in nasal secretions and urine (Gumperlein et al., 2018).

Relative to adults, children inhale more air per unit of body weight at a given level of exertion and their internal air passageways are smaller, which means more lung tissue surface area is exposed per volume of air (ICRP, 1994). Because the internal diameter of the airways in a child is narrower, any inflammation or obstruction may cause more severe distress (Wyper et al., 2019). While not novel, the notion that children are more susceptible to air pollution inhalation exposure because of their underdeveloped cardiopulmonary and immune systems is understudied. This data gap has been generally agreed upon since 2010 (Brook et al., 2010) and currently the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency uses a series of air quality indices (AQI) to categorize exposure to particulate matter having an aerodynamic diameter smaller than 2.5 μm (PM2.5). The AQI for “Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups” concentrations extends from 35.5–55.4 μg/m3 and “Unhealthy” at concentrations 55.5–150.4 μg/m3 (U.S. EPA, 2012). Children exposed to PM2.5 concentration levels that exceeded this recommended unhealthy level display elevated pulmonary arterial blood pressure and an increased asthma prevalence (Calderon-Garciduenas et al., 2007; Keet et al., 2018). Given that FFF-based 3-D printing generates emissions that contain PM2.5 as well as organic vapors (Azimi et al., 2016; Bharti et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2016; Floyd et al., 2017; Geiss et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2017; Mendes et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017; Stabile et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2017, 2018; Steinle, 2016; Stephens et al., 2013; Vaisanen et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2015; Zontek et al., 2017), it is imperative to identify whether such emissions also emanate from similar products marketed as children’s toys. This issue is further relevant as children’s toy 3-D printers and pens operate under very different conditions than traditional desktop- and industrial-scale FFF-based 3-D printers.

This research sought to characterize the particle and vapor emissions from toy 3-D pens and a toy 3-D printer to model particle deposition in the lung and organic vapor exposure for children. It is necessary to understand the characteristics of emissions in order to evaluate exposure potential and develop informed decisions with regard to regulations, recommendations, guidelines, or instructions for use of these toys by children.

Materials and Methods

All toys were evaluated using an emission characterization system (Stefaniak et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2016). The system consisted of: 1) a 0.6 m3 stainless steel test chamber (TSE Systems, Chesterfield, MO); 2) a toy 3-D pen or printer; and, 3) air monitoring instrumentation. The chamber had a front glass door, an inlet on the bottom and an outlet on the top, and sampling ports located on the sloped top walls (see Figure 1). The chamber floor is made of a perforated stainless steel sheet and upward airflow through the sheet promotes mixing in the chamber. Stainless-steel sampling tubes extend from the sampling ports into the center of the chamber to sample air. A two-piece high efficiency particulate air filter and activated carbon filter (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) was attached to the chamber air inlet to remove particles and organic chemicals, respectively, prior to entering the chamber. Prior to testing, the chamber leak rate and air exchange rate were determined by dosing the chamber with sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and monitoring its concentration using an infrared spectrophotometer (Miran Sapphire, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The leak rate over an eight-hour period was found to be 0.8% under static conditions and the air exchange rate was 1.4 air changes per hour using an exhaust flow-rate equal to that of all sampling equipment combined (ASTM, 2013; ISO, 2007).

The concentration and size distribution profiles of emitted particles were measured using an electrical low-pressure impactor (ELPI) with a measurement size range of 24 nm to 9,380 nm (ELPI Classic, Dekati Ltd., Tampere, Finland) and a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS) with a measurement size range of 14 nm to 1,000 nm (model 3910, TSI Inc., Shoreview, MN). Personal sampling pumps (GilAir5, Sensidyne, LP, St. Petersburg, FL) calibrated at 4 L/min and connected to plastic cassette samplers containing filter media were used to collect particles for off-line characterization. These pumps were operated using their internal timers to turn on and off to avoid opening the chamber during sampling. Track-etched polycarbonate filters (3-μm pore size) in open-faced cassettes were used to collect particles for analysis using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, S-4800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an energy dispersive x-ray (EDX) analyzer (Quantax, Bruker Scientific Instruments, Berlin, Germany) to determine particle morphology and elemental composition, respectively. Separate pumps with mixed cellulose ester (MCE, 5-μm pore size) filters in closed-face cassettes were used to collect particles for quantification of elements by mass spectrometry.

The concentration of metals in unused bulk filament and in particles captured on MCE filters (during extrusion with the XYZ brand pens and printer only) was determined using microwave-assisted acid digestion and analysis by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Briefly, each sample was transferred to a Teflon® digestion vessel and 9- and 3-mL of TraceMetal™ Grade nitric and hydrochloric acid (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were added to the vessel, respectively. The samples were digested in a microwave (MARSXpress, CEM, Matthews, NC) following EPA method 3051A. Elemental composition and concentrations were determined by ICP-MS (Agilent 7900, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in accordance with EPA Method 6020. The instrument was tuned daily using a 10 ppb solution of Ce, Co, Li, Mg, Tl, and Y in 2% nitric acid from Agilent and a 1 ppm solution of 6-Li, Sc, Ge, Rh, In, Tb, Lu, and Bi in 2% nitric acid from Agilent was used as an internal standard. The glassware used consisted of 0.4 mL/min flow concentric glass MicroMist™ nebulizer, quartz Scott-style spray chamber, straight quartz connector, and quartz torch with 2.5 mm injector from Glass Expansion (Pocasset, MA). Instrument settings consisted of 1500 W RF power, 15.00 L/min plasma gas flow rate, 1.1 L/min carrier gas flow rate, 0.9 L/min auxiliary gas flow rate, and 2 °C spray chamber temperature. All results were background-corrected for the presence of any elements by identical treatment and analysis of unused MCE filters.

Total VOC (TVOC) concentration in the chamber was measured using a real-time photoionization detector with 10.6 eV ultraviolet discharge lamp (Model 3000 ppbRAE, RAE Systems, San Jose, CA). This instrument was factory calibrated using isobutylene and span checked with isobutylene prior to use and is capable of measuring down to 1 ppb (2.3 μg/m3 isobutylene equivalent). Measurement results in ppb were converted to μg/m3 isobutylene equivalents using the molecular weight of isobutylene. Samples of VOCs were collected using whole-air 6 L Silonite®-coated canisters (Entech Instruments, Inc., Simi Valley, CA) followed by off-line analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS, Model 7890–5975, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) to quantify 17 VOCs (NIOSH, 2018) plus acetaldehyde and styrene. Two canister samples were collected during replicate printing tests, one during the background phase and the other at the mid-point of the printing phase. Collection took a period of about 1 to 2 min per sample.

To evaluate emissions, one pen (clamped to a ring stand) or printer was placed in the center of the test chamber about 10 cm from the sample probe inlets (Figure 1). For the pens, a second ring stand was used to hold a spool that contained a known length of filament, which was fed into the pen. With a toy in the chamber but unplugged, levels of organic vapors and particles were monitored for 30 to 60 minutes to ensure a low stable background. After the background phase, the toy was plugged into an electrical receptacle located outside of the chamber to begin heating the extruder nozzle to the required temperature (dependent on filament and toy). For the pens, a rubber band was wrapped around the extruder buttons to depress them and when the extruder reached its set temperature the pen began to extrude filament without opening the chamber door. To stop extrusion, the pen was unplugged. The toy printer was connected via a USB cable to a laptop computer outside of the chamber and printing was started and stopped using the computer without opening the chamber door.

First, three of the same brand and model of 3-D pen having 0.7 mm diameter extrusion nozzle (Scribbler 3D pen, Gagarin LLC, China) were evaluated to test the influences of filament extrusion speed and pen on emissions. The extrusion speed for the Scribbler pens was operated at its highest and lowest settings to observe the range of potential emissions. Filament extrusion was performed using two common types of filament, ABS (natural color) and PLA (translucent blue color); both filaments are from MakerBot Industries, LLC (Brooklyn, NY) and from the same lot as used in our previous studies (Stefaniak et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2016). The extruder temperatures for the Scribbler pen were pre-programmed by the manufacturer; according to the digital display on the pen, it was approximately 230 °C for ABS and 210 °C for PLA. Each combination of filament extrusion speed and pen was tested in triplicate by extruding ABS or PLA filament for 40 minutes.

Next, three of the same brand and model of 3-D pen toy having 0.8 mm diameter extrusion nozzle (da Vinci 3D pen, XYZprinting, Inc., San Diego, CA) were evaluated to test the influence of filament color on emissions. The da Vinci 3-D pens have a single factory-default filament extrusion speed that is not adjustable by the user. Clear yellow PLA and clear orange PLA filaments (both 1.75 mm diameter, XYZprinting, Inc.) were extruded for 40 minutes each. The XYZ pen does not have a display for the extruder nozzle temperature but it is stated to be 190 °C by the manufacturer. Each combination of pen and filament color was tested in triplicate.

Finally, emissions were measured for one brand of toy 3-D printer (da Vinci miniMaker, XYZprinting, Inc.) that only uses PLA filament to test whether emissions differed from the 3-D pens. The same PLA filament colors that were used with the 3-D pens were evaluated in the toy printer. All filaments were extruded through a 0.4 mm diameter nozzle for about 42 minutes to print a rose flower stem (Figure 1). The temperature of the extruder nozzle ranged from 200 to 210 °C during printing. Each filament color was tested in triplicate.

Calculation of emission yields

Emission rates were calculated using the measurement data from each real-time monitoring instrument and the masses of individual elements on MCE filters for the XYZ brand pens and printer. To account for differences in extruded polymer mass, all emission rates were multiplied by the extrusion time to determine total number of particles, mass of element, or mass of TVOC emitted, and normalized to the mass of material extruded to express results as yields (Kim et al., 2015). All emission rates were calculated in accordance with the standard RAL-UZ-171 for determination of emissions from office equipment (BAM, 2017). As specified in this standard, each emission rate was calculated for the printing phase (from start to end of extrusion) until one air exchange had occurred in the post-operating phase (extrusion complete, toy pen or printer off).

Inhalation exposure modeling for VOCs

TVOC emission rates were used to model concentration values for a classroom and residential living room as prescribed in ANSI/CAN/UL 2904: Standard Method for Testing and Assessing Particle and Chemical Emissions from 3D Printers (UL, 2019):

| Equation (1) |

Where, CTVOC = estimated TVOC exposure concentration (μg/m3), ERTVOC = TVOC emission rate (μg/hour), A = number of 3-D pens or printers operating in the model room, Vm = volume of the model room (m3), and Nm = air exchange rate in the model room (per hour). For the classroom model, values of Vm = 231 m3 and Nm = 0.82/hr with occupancy of 27 students are default values for a typical classroom (UL, 2019). The number of 3-D pens was one or 27 to simulate one or all students using a toy and the number of 3-D printers was set to one. For the residential model, a value of Vm = 163.1 m3 (living room) and Nm = 0.23/hr are default values (UL, 2019). The number of emitting sources was varied from one to three to simulate one or multiple children simultaneously using their own 3-D pen and set to one for the 3-D printer.

Respiratory dose modeling for particles

The fraction of particles that could deposit in the respiratory tract were calculated using the Multiple-Path Particle Dosimetry model (MPPD, v3.04, ARA) for children of varying ages (Asgharian et al., 2001). Dose estimates were calculated using the SMPS measurements and age-specific five-lobe lung model for 3-, 8-, and 14-year old children who are oronasal normal augmenter breathers. This range of ages was chosen to represent children who may use a toy (8- and 14-year olds) or be near a child using a toy (3-year olds). Model parameters for 3 year old children were as follows: forced residual capacity (FRC) = 48.2 mL, upper respiratory tract (URT) volume = 9.47 mL, breaths per minute (bpm) = 24, and tidal volume = 121.3 mL. For 8+ year old children, values were: FRC = 501.32 mL, URT = 21.03 mL, bpm = 17, and tidal volume = 278.2 mL. For 14 year old children, the parameters were: FRC = 987.56 mL, URT volume = 30.63 mL, bpm = 14, and tidal volume = 388.1 mL. For all ages, the inspiratory fraction = 0.5.

Statistical analyses

Statistics were computed in JMP (version 13, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) as detailed in the results, using a significance level of α = 0.05 for all comparisons. All statistics were computed using log-transformed yield values and geometric mean particle size values. For the Scribbler pens, mixed-effects models using the default co-variance structure (variance components) were fit separately for particle yield values, particle size values, and TVOC yield values to determine the influence of extrusion speed (fixed effect) and pen (random effect) on emissions for each filament type. For the XYZ pens, mixed-effects models were fit separately for each outcome variable (particle yield, etc.) to determine the influence of filament color (fixed effect) and pen (random effect) on emissions. For the XYZ printer, linear regression models were used to determine the influence of filament color on emissions. Finally, mixed models were used to explore factors that could explain differences in emissions among brands of pens and printer. For all comparisons, Tukey’s multiple comparison was used to compare means across different levels of a variable.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the concentrations of aluminium (Al), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn), the three most abundant metals in the bulk filaments tested. Vanadium (V, up to 0.001 mg/kg), titanium (Ti, up to 0.002 mg/kg), copper (Cu, up to 0.004 mg/kg), and chromium (Cr, 0.008 mg/kg) and traces of antimony (Sb), cadmium (Cd), cobalt (Co), manganese (Mn), and nickel (Ni) were observed and measured in all filaments. Arsenic (As) was observed in PLA filaments only (up to 0.001 mg/kg). All filaments contained sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), and calcium (Ca).

Table 1.

Average (± standard deviation) levels of metals in bulk filaments (mg/kg)

| Metala | ABS/natural | PLA/translucent blue | PLA/clear yellow | PLA/clear orange |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | 0.036±0.002 | 0.047±0.003 | 0.032±0.013 | 0.035±0.006 |

| Iron | 0.023±0.005 | 0.042±0.041 | 0.037±0.023 | 0.034±0.011 |

| Zinc | 0.015±0.002 | 0.016±0.004 | 0.008±0.001 | 0.030±0.002 |

All results were obtained using helium gas collision mode

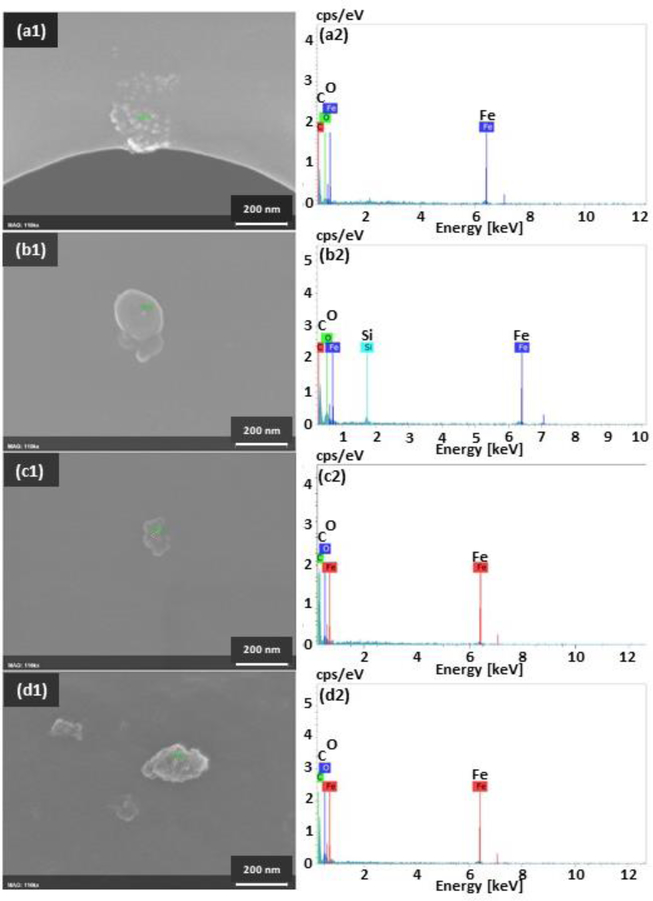

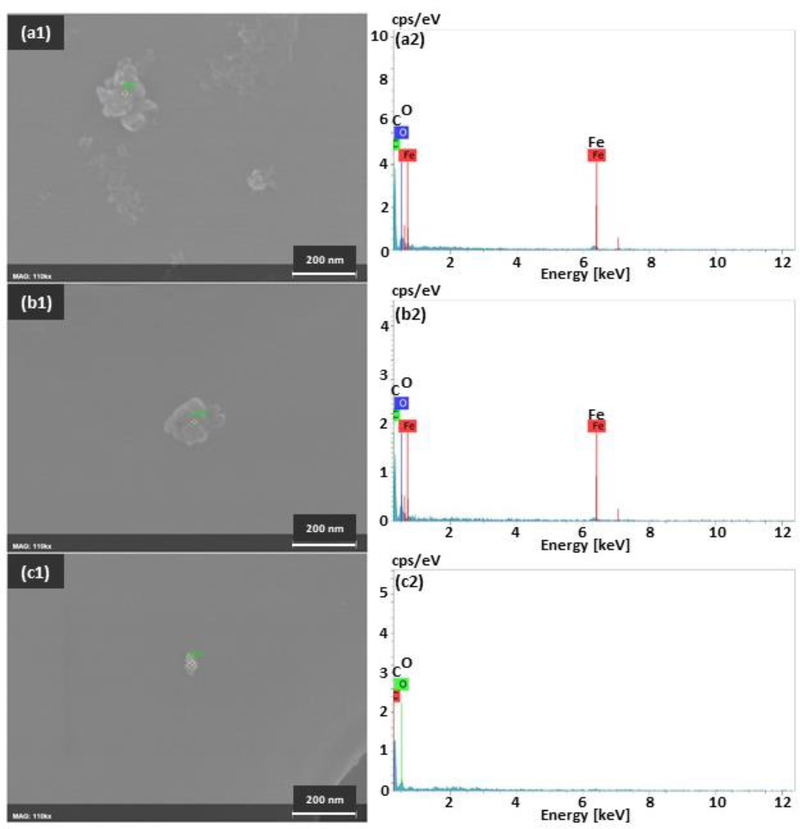

Figure 2 shows micrographs and EDX spectra for particles emitted during testing of the 3-D pens with ABS and PLA filaments. In general, particle sizes ranged from tens to a few hundred nanometers with occasional micron-scale particles observed in images. Carbon (C) and oxygen (O) were detected in all spectra. Some particles emitted during extrusion of natural ABS contained Fe (see Figure 2a), Mn, or silicon (Si) whereas for translucent blue PLA, Fe and Si, but not Mn were present in particles (Scribbler pens). Extrusion of clear yellow and orange PLA yielded some particles that contained Fe and a few particles that contained both Ni and Fe (XYZ pens). Figure 3 is representative micrographs and EDX spectra for particles emitted during extrusion of PLA filaments with the miniMaker toy 3-D printer. In general, printing with translucent blue and clear yellow and orange PLA filaments yielded particles with morphological and elemental characteristics similar to those from the 3-D pens.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs and energy dispersive x-ray spectra for particles emitted during testing of the 3-D pens with ABS and PLA filaments: (a1, a2) Scribbler pen natural ABS, (b1, b2) Scribbler pen translucent blue PLA, (c1, c2) XYZ pen clear yellow PLA, and (d1, d2) XYZ pen clear orange PLA. Note: colors of tags with elemental symbols are randomly assigned by computer software and do not imply differences in levels of elements.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrographs and energy dispersive x-ray spectra for particles emitted during testing of the XYZ miniMaker 3-D printer toy with PLA filaments: (a1, a2) translucent blue PLA, (b1, b2) clear yellow PLA, and (c1, c2) clear orange PLA. Note: colors of tags with elemental symbols are randomly assigned by computer software and do not imply differences in levels of elements.

Table 2 summarizes the calculated emission yields of elements quantified by ICP analysis of filter samples collected during extrusion of translucent blue, clear orange, and clear yellow PLA filaments with XYZ 3-D pens and a XYZ miniMaker 3-D printer. Sixteen elements were quantified on the filters and several of these were also quantified in the bulk filaments by ICP analysis and identified in the aerosol using EDX analysis of individual particles (i.e., Al, Ca, Co, Fe, Mg, Na, Ni, Si, and Zn). Emission yields varied by filament color and between individual pens extruding the same color. Silicon was present in eight of the nine filament color/toy combinations tested and yields ranged from 15 – 107 ng/g printed. Iron was present in three of the nine combinations tested (range: 127 – 3168 ng/g printed). Other emissions of health interest included Co (0.03 – 0.005 ng/g printed), Mn (1.6 – 92.3 ng/g printed), Mo (0.04 – 0.26 ng/g printed), Pb (0.13 – 1.2 ng/g printed), Sn (0.17 – 0.24 ng/g printed), and Sr (0.10 – 0.95 ng/g printed).

Table 2.

Elemental emission yields for aerosol released by PLA filaments extruded with XYZ brand pen and printer toys (elemental masses quantified by ICP analysis)

| Yield (ng/g printed)a |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear yellow | Clear orange | Translucent blue | |||||||

| Element | Pen A | Pen B | Pen C | Printer A | Pen A | Pen B | Pen C | Printer A | Printer A |

| Al | -- | -- | 372.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Be | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.13 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ca | -- | -- | 191.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 503.6 |

| Co | -- | -- | 0.03 | -- | 0.005 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Fe | -- | -- | 127.0 | -- | 439.5 | -- | -- | -- | 3168.0 |

| Mg | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 10.3 |

| Mn | -- | -- | 1.6 | -- | 13.8 | -- | -- | -- | 92.3 |

| Mo | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.22 | -- | -- | 0.04 | 0.26 |

| Na | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 11.9 | -- |

| Ni | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 3.0 | -- |

| P | -- | -- | -- | 5.6 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | 61.6 |

| Pb | 0.13 | 1.2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Si | 15.3 | -- | 22.5 | 106.6 | 41.7 | 16.0 | 22.5 | 92.6 | 25.2 |

| Sn | -- | 0.24 | 0.17 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Sr | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | 0.95 |

| Zn | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 42.8 |

Each reported yield value was calculated from a single composite filter sample collected over all three replicates of a toy/filament combination. Elemental symbols in bold font were detected in bulk filament and quantified in aerosol using ICP analysis. Yield values in italics indicate the element was also identified in aerosol using EDX analysis.

-- = Element not detected on sample

Factors influencing emissions from Scribbler toy 3-D pens

Table 3 summarizes the emissions from the Scribbler 3-D pens. Based on the mixed-effects modeling results, ELPI and SMPS particle yield values were significantly higher at the slow extrusion speed compared with the fast speed for both ABS and PLA filaments (p <0.05). Geometric mean (GM) particle sizes measured using the ELPI (189.4 versus 217.4 nm) and SMPS (139.5 versus 173.8 nm) instruments for ABS filament were significantly smaller at the slow extrusion speed compared with the fast speed (p <0.05). For PLA filament, there was no difference in GM particle sizes for the ELPI measurements, though the sizes measured using the SMPS instrument were significantly smaller at the slow extrusion speed compared with the fast speed (p <0.05). GM TVOC yield values were significantly higher for the slow extrusion speed for both types of filaments (p<0.05). For natural ABS, VOC concentrations were (background corrected values, μg/m3): acetaldehyde (<background – 393.6), acetone (3.1 – 18.2), benzene (1.1 – 1.5), ethanol (<background – 187.5), ethylbenzene (368.7 – 647.3), isopropyl alcohol (<background – 19.3), styrene (1318 – 2216), and toluene (2.4 – 4.4). For translucent blue PLA, concentrations were (background corrected values, μg/m3): acetone (<background – 22.4), benzene (<background – 1.4), ethanol (<background – 73.9), ethylbenzene (<background – 0.9), isopropyl alcohol (<background – 62.5), methyl methacrylate (<background – 1.7), styrene (<background – 3.2) and toluene (<background – 0.2).

Table 3.

Geometric mean (95% confidence interval) emission characteristics for Scribbler brand toy 3-D pens at two extrusion speeds for two common types of filaments (n = 9; 3 pens × 3 replicates/pen)

| ABS/natural |

PLA/translucent blue |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device extrusion speed setting |

Device extrusion speed setting |

|||

| Metrica | Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast |

| ELPI yield (#/g printed) | 3.2 × 1010 (1.7 – 6.0 × 1010)* | 4.1 × 109 (2.2 – 7.7 × 109) | 6.4 × 109 (0.4–1.1 × 1010)† | 1.4 × 109 (0.8 – 2.5 × 109) |

| SMPS yield (#/g printed) | 3.5 × 1010 (1.6 – 7.8 × 1010)* | 3.6 × 109 (1.6 – 7.9 × 109) | 5.3 × 1010 (0.2 – 1.3 × 1011) † | 9.4 × 108 (0.4 – 2.3 × 109) |

| ELPI size (nm) | 189.4 (150.3 – 238.5)* | 217.4 (172.6 – 273.8) | 70.7 (60.9 – 82.1) | 77.5 (66.7 – 99.0) |

| SMPS size (nm) | 139.5 (121.8 – 159.8)* | 173.8 (151.7 – 199.1) | 33.9 (30.8 – 37.3)† | 46.2 (41.9 – 50.8) |

| TVOC yield (μg/g printed) | 496.5 (328.6 – 750.7)* | 134.7 (88.4 – 205.2) | 35.5 (16.1 – 78.4)† | 9.9 (4.6 – 21.5) |

ELPI = electrical low pressure impactor; SMPS = scanning mobility particle sizer; TVOC = total volatile organic compound

= significantly different between slow and fast device extrusion speed settings for ABS filament (p < 0.05)

= significantly different between slow and fast device extrusion speed settings for PLA filament (p < 0.05)

Factors influencing emissions from XYZ toy 3-D pens

Table 4 summarizes the emission characteristics of the XYZ pens. From the mixed-effect modeling results, the GM particle and TVOC yields were significantly higher and particle sizes were significantly smaller for clear yellow PLA compared with clear orange PLA. Analysis of canister samples for individual VOCs suggest a possible difference by filament color for methyl methacrylate, which appeared higher for clear yellow PLA (158.4 – 234.7 μg/m3) compared with clear orange PLA (<background – 5.7 μg/m3).

Table 4.

Geometric mean (95% confidence interval) emission characteristics for XYZ brand toy 3-D pens extruding two colors of PLA filament at a constant extrusion speed (n = 9; 3 pens × 3 replicates/pen)

| Metrica | PLA/clear yellow | PLA/clear orange |

|---|---|---|

| ELPI yield (#/g printed)* | 5.2 × 109 (0.2 – 1.2 × 1010) | 1.8 × 108 (0.8 – 4.0 × 108) |

| SMPS yield (#/g printed)* | 2.1 × 1010 (0.8 – 5.2 × 1010) | 1.9 × 108 (0.8 – 4.9 × 108) |

| ELPI size (nm)* | 60.8 (55.8 – 66.3) | 103.1 (94.6 – 112.3) |

| SMPS size (nm)* | 32.3 (29.7 – 35.2) | 59.6 (54.7 – 64.8) |

| TVOC yield (μg/g printed)* | 31.8 (25.7 – 39.4) | 10.8 (8.7 – 13.4) |

ELPI = electrical low pressure impactor; SMPS = scanning mobility particle sizer; TVOC = total volatile organic compound

= significantly different between colors (p <0.05)

Factors influencing emissions from XYZ toy miniMaker 3-D printer

Table 5 summarizes the emissions characteristics of the miniMaker 3-D printer for three PLA filament colors. Based on the linear regression models, there was no difference in GM particle yield values calculated from ELPI data; however, the yield value for clear orange PLA from SMPS data was significantly lower than the other colors (p <0.05). There was no difference in GM sizes of emitted particles measured using the ELPI; however, sizes measured using the SMPS were significantly (p <0.05) smaller for clear yellow compared with the other colors. The mean TVOC yield value for clear yellow PLA appeared higher compared with clear orange PLA filament (p = 0.055). The TVOC levels in the chamber were near or below the photoionization instrument limit of detection while extruding translucent blue PLA filament, which precluded calculation of an emission yield value. Levels of acetone were below background for translucent blue PLA, up to 2.6 μg/m3 for clear orange PLA, and up to 6.4 μg/m3 for clear yellow PLA. Levels of benzene did not exceed 0.7 μg/m3 for all filament colors and isopropyl alcohol (4.7 μg/m3) was above background only for translucent blue PLA. Methyl methacrylate concentrations were highest for clear yellow PLA (64.6 – 69.1 μg/m3) followed by translucent blue PLA (<background – 2.8 μg/m3) and clear orange PLA (<background – 0.5 μg/m3).

Table 5.

Geometric mean (95% confidence interval) emission characteristics for XYZ brand toy miniMaker 3-D printer extruding three colors of PLA filament at a constant extrusion speed (n = 3; 1 printer × 3 replicates/printer)

| Metrica | PLA/translucent blue | PLA/clear yellow | PLA/clear orange |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELPI yield (#/g printed) | 3.8 × 107 (1.5 – 9.6 × 107) | 6.1 × 106 (0.2 – 1.6 ×107) | 8.5 × 106 (0.3 – 2.2 × 107) |

| SMPS yield (#/g printed)* | 3.5 × 107 (2.2 – 5.6 × 107) | 4.5 × 107 (2.8 – 7.2 × 107) | 3.5 × 106 (2.2 – 5.7 × 106) |

| ELPI size (nm) | 174.2 (138.6 – 218.9) | 147.9 (117.7 – 185.8) | 202.3 (161.0 – 254.3) |

| SMPS size (nm)† | 54.9 (50.8 – 59.3) | 39.9 (37.0 – 43.1) | 48.7 (45.1 – 52.6) |

| TVOC yield (μg/g printed)‡ | --b | 11.5 (6.9 – 19.0) | 4.4 (2.7 – 7.3) |

ELPI = electrical low pressure impactor; SMPS = scanning mobility particle sizer; TVOC = total volatile organic compound

TVOC levels near or below photoionization detector instrument detection limit which precluded calculation of yield value

= clear orange significantly different from translucent blue and clear yellow filaments (p < 0.05)

= clear yellow significantly different from translucent blue and clear orange filaments (p < 0.05)

= clear yellow borderline significantly different from clear orange filament (p = 0.055)

Factors influencing differences in emissions among toys

As summarized in Table 6, mixed models identified extruder nozzle diameter (Dnozzle), extruder nozzle temperature (Tnozzle), extrusion speed setting of the toy (slow, fast, constant), filament type (ABS or PLA), and filament color as factors that influenced the observed emissions among toys. Dnozzle was significant among all levels (0.4, 0.7, and 0.8 mm) for ELPI and SMPS particle number yields (p < 0.05), with the largest increases in yields when nozzle diameter increased from 0.4 to 0.7 mm. Dnozzle was borderline significant among all levels for GM particle size measured using an ELPI instrument (but not an SMPS), with size decreasing as nozzle diameter increased (p = 0.05). Tnozzle was significant (p <0.05) for all metrics, except particle number yield values calculated from SMPS data. ELPI particle number yield significantly increased when Tnozzle increased from 210 to 230 °C (p <0.05) and TVOC yield significantly increased as Tnozzle increased to 230 °C (p <0.05). Further, Tnozzle was significant for ELPI and SMPS GM particle sizes (p <0.05 for both instruments), with a three- to four-fold increase in particle diameters as Tnozzle increased from 190 to 230 °C. The device extrusion speed setting had a significant effect on particle number and TVOC yields between the constant and slow speed settings (all p <0.05); there was no effect on particle size. Filament type was significant for ELPI particle number yield and TVOC yield, with values being higher for ABS compared with PLA filament (p <0.05). Filament type also impacted particle size, with GM size being larger for ABS compared with PLA (p <0.05). Filament color was the only factor that was significant for all emission metrics. Particle number and TVOC yields were greater and GM particle sizes larger (all p <0.05) for natural color compared with the translucent and clear colors. Particle size measured using an SMPS instrument for transparent orange PLA was larger than for translucent blue or clear yellow.

Table 6.

Mixed model results of factors influencing particle and TVOC emissions among brands of 3-D pen and printera

| Yields | GM Particle size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | ELPI (#/g printed) | SMPS (#/g printed) | TVOC (μg/g printed) | ELPI (nm) | SMPS (nm) |

| Dnozzle (mm) | |||||

| 0.4 | A1.3 × 107 (0.2 – 6.8 × 107) | A1.8 × 107 (0.2 – 20.4 × 107) | 7.1 (1.0 – 48.3) | 173.4 (101.6 – 295.7) | 47.4 (23.6 – 95.3) |

| 0.7 | B5.9 × 109 (2.5 – 11.4 × 109) | B8.9 × 109 (2.6 – 30.3 × 109) | 70.6 (32.3 – 154.3) | 122.5 (93.8 – 160.1) | 78.5 (55.4 – 111.2) |

| 0.8 | C1.0 × 109 (0.3 – 3.2 × 109) | B2.0 × 109 (0.4 – 11.4 × 109) | 18.5 (6.1 – 56.0) | 79.2 (54.3 – 115.5) | 43.9 (26.8 – 71.9) |

| Tnozzle (°C) | |||||

| 190 | 9.7 × 108 (1.5 – 62.0 × 108) | 2.0 × 109 (0.2 – 21.7 × 109) | A18.5 (9.5 – 36.3) | A79.2 (59.3 – 105.7) | A43.9 (36.2 – 53.2) |

| 210 | A4.8 × 108 (1.1 – 22.0 × 108) | 9.6 × 108 (1.4 – 66.5 × 108) | A14.7 (8.2 – 26.4) | A98.3 (77.7 – 124.4) | A42.0 (35.9 – 49.2) |

| 230 | B1.1 × 1010 (0.2 – 7.3 × 1010) | 1.1 × 1010 (0.1 – 12.1 × 1010) | B265.9 (135.6 – 521.1) | B202.9 (152.0 – 270.8) | B155.7 (128.5 – 188.7) |

| Device speed setting | |||||

| Constant | A2.3 × 108 (0.6 – 8.2 × 108) | A4.2 × 108 (0.9 – 19.4 × 108) | A14.6 (5.9 – 36.0) | 102.8 (72.3 – 146.3) | 45.0 (30.3 – 67.0) |

| Fast | 2.4 × 109 (0.5 – 11.6 × 109) | 1.8 × 109 (0.3 – 12.0 × 109) | 37.5 (13.2 – 106.5) | 129.8 (84.3 – 199.9) | 89.6 (55.1 – 145.6) |

| Slow | B1.4 × 1010 (0.3 – 6.9 × 1010) | B4.3 × 1010 (0.7 – 28.5 × 1010) | B132.8 (46.8 – 376.9) | 115.7 (75.1 – 178.2) | 68.8 (42.3 – 111.7) |

| Filament type | |||||

| ABS | A1.1 × 1010 (0.2 – 7.1 × 1010) | 1.1 × 1010 (0.1 – 11.5 × 1010) | A265.9 (137.5 – 514.1) | A202.9 (151.6 – 271.5) | A155.7 (127.0 – 187.9) |

| PLA | B6.4 × 108 (2.0 – 20.2 × 107) | 1.3 × 109 (0.3 – 5.6 × 109) | B16.2 (10.6 – 25.0) | B90.2 (75.0 – 108.4) | B42.8 (38.0 – 48.1) |

| Filament color | |||||

| Natural | A1.1 × 1010 (0.2 – 6.1 × 1010) | A1.1 × 1010 (0.1 – 8.8 × 1010) | A265.9 (142.6 – 495.6) | A202.9 (151.8 – 271.1) | A155.7 (135.8 – 178.5) |

| Translucent blue | 1.6 × 109 (0.3 – 7.6 × 109) | 3.3 × 109 (0.5 – 22.2 × 109) | B18.8 (10.1 – 34.9) | B83.6 (63.9 – 109.4) | B41.5 (36.5 – 47.0) |

| Clear orange | B8.4 × 107 (1.1 – 65.9 × 107) | B7.1 × 107 (0.6 – 88.8 × 107) | B8.6 (4.0 – 18.5) | 112.8 (79.1 – 160.9) | C56.6 (47.9 – 67.0) |

| Clear yellow | 9.6 × 108 (1.2 – 74.9 × 108) | 4.5 × 109 (0.4 – 56.1 × 109) | B24.7 (11.5 – 52.8) | B82.2 (57.6 – 117.2) | B34.1 (28.8 – 40.3) |

Values are means (95% confidence intervals); bold = statistically significant (p <0.05)

= different letters indicate significant difference between levels; Same or no letter indicates no difference between levels

TVOC exposure modeling

Table 7 summarizes the measured TVOC emission rates and modeled exposure concentrations for a toy 3-D pen or 3-D printer if used in a school classroom or residential living room. For one 3-D pen (Scribbler or XYZ brand), the estimated TVOC concentrations in a classroom ranged from 1 – 3 μg/m3 (PLA) and from 23 – 31 μg/m3 (natural ABS). For the miniMaker 3-D printer using clear yellow and orange PLA filaments, the exposure concentrations were lower than the 3-D pens. In a residential living room, the estimated TVOC exposure concentrations from use of a single 3-D pen ranged from 6 – 16 μg/m3 (PLA) and from 117 – 154 μg/m3 (ABS) and for the miniMaker toy 3-D printer using clear yellow and orange PLA filaments it ranged from 3 – 7 μg/m3.

Table 7.

Modeled TVOC exposure concentrations (CTVOC) from use of one toy 3-D pen or printer

| CTVOC (μg/m3) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toy | Model | Filament | ER (μg/hr)a | Classroom | Living room |

| Pen | Scribbler | PLA/translucent blue/slow | 231 | 2 | 11 |

| PLA/translucent blue/fast | 511 | 3 | 14 | ||

| ABS/natural/slow | 4393 | 23 | 117 | ||

| ABS/natural/fast | 5793 | 31 | 154 | ||

| Pen | XYZ | PLA/clear yellow | 617 | 3 | 16 |

| PLA/clear orange | 231 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Printer | miniMaker | PLA/translucent blue | --b | NA | NA |

| PLA/clear yellow | 111 | 0.6 | 3 | ||

| PLA/clear orange | 273 | 1 | 7 | ||

Average TVOC emission rate from real-time photoionization instrument

TVOC levels at or below real-time photoionization instrument limit of detection which precluded calculation of an emission rate

Particle lung deposition modeling

Table 8 summarizes the particle deposition estimates for the head region (anterior nasal passages and extrathoracic region), bronchiolar (trachea and large bronchi and bronchioles), and pulmonary (alveolar interstitial) regions of the respiratory tract for 3-, 8- and 14-year old children. Depositions estimates were calculated using the size distributions from the SMPS measurement data. Data from the Scribbler pens indicated that extrusion speed influenced regional particle lung deposition estimates. In the head region, because of their larger size, deposition fractions of ABS and PLA particles were higher at the fast filament extrusion speed compared with the slow speed. For the bronchiolar and pulmonary regions, deposition fractions for ABS particles were higher at the fast extrusion speed compared with the slow speed; the opposite was true for the PLA filament. Filament type also had an influence on particle lung deposition estimates. ABS particle deposition fractions in the head region were higher than PLA particles at equal extrusion speed. In contrast, deposition fractions for the bronchiolar and pulmonary regions were higher for PLA particles compared with ABS particles at the same extrusion speed.

Table 8.

Particle deposition fractions in the head, bronchiolar (B), and pulmonary (P) lung regions for children using toy3-D pens and printer

| 3-year old |

8-year old |

14-year old |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toy | Model | Filament | GM (GSD)a | Head | B | P | Head | B | P | Head | B | P |

| Pen | Scribbler | PLA/trans blue/slow | 33.9 (1.51) | 0.104 | 0.110 | 0.378 | 0.087 | 0.109 | 0.497 | 0.072 | 0.112 | 0.413 |

| PLA/trans blue/fast | 46.2 (1.64) | 0.132 | 0.078 | 0.314 | 0.123 | 0.079 | 0.405 | 0.087 | 0.085 | 0.329 | ||

| ABS/natural/slow | 139.5 (2.10) | 0.233 | 0.039 | 0.171 | 0.235 | 0.042 | 0.231 | 0.179 | 0.045 | 0.192 | ||

| ABS/natural/fast | 173.8 (2.26) | 0.264 | 0.051 | 0.201 | 0.262 | 0.058 | 0.275 | 0.222 | 0.057 | 0.239 | ||

| Pen | XYZ | PLA/clear yellow | 32.4 (1.45) | 0.107 | 0.120 | 0.388 | 0.088 | 0.119 | 0.513 | 0.076 | 0.127 | 0.430 |

| PLA/clear orange | 60.4 (1.64) | 0.134 | 0.067 | 0.283 | 0.128 | 0.068 | 0.361 | 0.088 | 0.073 | 0.289 | ||

| Printer | miniMaker | PLA/trans blue | 55.0 (1.79) | 0.139 | 0.061 | 0.261 | 0.135 | 0.064 | 0.332 | 0.091 | 0.068 | 0.264 |

| PLA/clear yellow | 40.0 (1.88) | 0.138 | 0.067 | 0.277 | 0.132 | 0.069 | 0.354 | 0.091 | 0.074 | 0.284 | ||

| PLA/clear orange | 48.8 (1.82) | 0.138 | 0.064 | 0.268 | 0.134 | 0.066 | 0.342 | 0.091 | 0.071 | 0.273 | ||

Size data from scanning mobility particle sizer and is the mean geometric mean (GM) and mean geometric standard deviation (GSD) for combination of variables

For the XYZ 3-D pen toys, in the head region, deposition of clear orange PLA particles was higher than clear yellow PLA particles and fractions varied by age. The opposite effect of color was observed in the bronchiolar and pulmonary regions, where deposition fractions were higher for clear yellow PLA particles compared with clear orange PLA particles.

The average GM size of particles emitted by the miniMaker toy 3-D printer using translucent blue and clear yellow PLA filaments were larger compared with the 3-D pens, which translated into lower pulmonary deposition fractions. For example, the calculated pulmonary deposition for a 3-year old child using the toy 3-D printer with translucent blue PLA was 26.1% compared with 31 – 38% for the same filament used in the Scribbler 3-D pen. The average GM size of particles emitted from the 3-D printer using clear orange PLA was slightly smaller compared with the XYZ pens, though deposition estimates were similar for all lung regions and ages.

Supplemental data

Supplemental Figures S1 – S9 are box plots of particle yield, particle GM size, and TVOC yield by toy. Tables S1 – S3 give the tabulated values by toy.

Discussion

Characterization of the bulk filament materials using ICP analysis quantified several metals of health significance, including Fe, Zn, V, and Cr as well as traces of Sb, Cd, Co, Mn, and Ni. Exposure to these metals is associated with a range of adverse health effects in adults, including cough, dyspnea, metal fume fever, and asthma (NIOSH, 2018). In children, exposure to Cr, Cd, and Mn is associated with adverse neurological effects and exposure to V and Fe among children with asthma is associated with changes in exhaled nitric oxide (Caparros-Gonzalez et al., 2019; Godri Pollitt et al., 2016; Hessabi et al., 2019). EDX analysis of individual particles released during extrusion of ABS and PLA filaments using the toy 3-D pens and printer identified Fe and occasionally Ni. ICP analysis of particles aerosolized and collected onto MCE filters during extrusion of PLA filaments with the XYZ brand pens and printer identified many of the same elements. These data indicate that some, but not all bulk filament constituents were aerosolized during extrusion with these toys.

Factors influencing particle emissions from toys

For the Scribbler pens, particle yields were generally higher and GM particle sizes were smaller at the slow extrusion speed (~ 1 mm/s) compared with the fast speed (~ 5 mm/s). Given that the extruder nozzle diameter was constant (0.7 mm), the higher yields at the slow extrusion speed is attributed to longer residence time of the filament in the extruder nozzle, which permitted more thermal breakdown of the polymer. Previously, Deng et al. (2016) evaluated the influence of extrusion speed on particle concentrations from ABS and PLA using a desktop-scale 3-D printer and reported that particle number concentration varied with extrusion speed.

For the XYZ pens, particle yields were higher and GM particle sizes were smaller for clear yellow PLA filament compared with clear orange PLA. In contrast, the particle emissions from the XYZ miniMaker toy printer were generally not influenced by PLA filament color. Hence, the influence of filament color on particle emission characteristics remain inconsistent in the literature, with some studies suggesting an influence and others studies indicating it has less of an impact compared with factors such as filament brand (Davis et al., 2019; Stefaniak et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017).

Direct comparison of particle yield data in Tables 3 – 5 to desktop-scale 3-D printers that use FFF technology is limited because different measurement methods and equations are used among investigators to calculate yield values (Byrley et al., 2019). With this limitation in mind, yield values for the Scribbler pens extruding ABS ranged from 109 to 1010 particles/g printed, which is within the range reported for desktop-scale 3-D printers, i.e., from 107 particles/g ABS printed to 1012 particles/g ABS printed (Floyd et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2018). For PLA, among all toys, emission yield values ranged from 106 particles/g printed to 1010 particles/g printed. For comparison, emission yields reported for desktop-scale 3-D printers using PLA filaments range from 107 particles/g printed to 1012 particles/g printed (Floyd et al., 2017; Stabile et al., 2017).

Factors influencing organic vapor emissions from toys

The higher TVOC yield for the Scribbler 3-D pens operated at the slow extrusion speed compared with the fast speed may be an effect of longer filament residence time in the heated extruder nozzle. However, there was no clear and consistent relationship between concentrations of individual VOCs and extrusion speed. The styrene emissions from extruding ABS are notable as this chemical has been implicated as a risk factor for asthma and other non-malignant respiratory diseases in adults and is present in homes of children with asthma (Chin et al., 2014; Moscato et al., 1987; Nett et al., 2017).

TVOC yield values were also influenced by filament color (XYZ pens, and to a minor extent, miniMaker printer). The influence of color on TVOC emission yields may be an effect of the dyes or plasticizers used to impart color. Comparison of TVOC emission yields from the toys to desktop-scale 3-D printers indicates that values are similar. For example, extrusion of natural ABS using the Scribbler pens had yields of about 70 to 590 μg TVOC/g printed compared with values for desktop-scale 3-D printers using ABS that range from about 60 μg to 780 μg TVOC/g printed (Floyd et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2017). Among all toys, TVOC emission yields for PLA filaments ranged from below the instrument limit of detection to 90 μg TVOC/g printed, compared with values for desktop-scale 3-D printers of less than detectable to 545 μg TVOC/g printed (Floyd et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2015; Stefaniak et al., 2017).

Concentrations of specific VOCs did not appear to be influenced by PLA filament color, with the exception of methyl methacrylate. Methyl methacrylate is considered a respiratory irritant, but its capacity as a respiratory sensitizer and asthmagen is unclear (Borak et al., 2011). For the XYZ pens, concentrations of methyl methacrylate emitted from clear yellow PLA ranged from about 160 to 230 μg/m3 compared with less than 6 μg/m3 for clear orange PLA. For the miniMaker toy 3-D printer, concentrations of methyl methacrylate for clear yellow PLA were about 65 to 69 μg/m3 compared with less than 3 μg/m3 for translucent blue and clear orange PLA filaments.

Factors explaining differences in emissions among toys

Five factors related to the toys and feedstock materials significantly influenced emissions among toys (Table 6). For particle number yield, Dnozzle had the most influence. For a given filament passing through a nozzle at the same speed, the larger the nozzle diameter the more filament surface area heated, and in turn, the greater the breakdown of the polymer and the higher the emissions. The largest change in particle number emission yield was observed when nozzle diameter increased from 0.4 to 0.7 mm (470- and 500-fold increase for the ELPI and SMPS values, respectively). The next most influential factor on particle number yield was toy extrusion speed setting, with values increasing 60- to 100-fold between the constant and slow settings. Previously, Deng et al. reported that extrusion speed may influence the concentration of released particles (Deng et al., 2016). Increasing Tnozzle from 210 to 230 °C resulted in 24-fold higher particle emission yield (ELPI only) which is consistent with prior reports that particle yield can increase as extruder nozzle temperature increases (Davis et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017). Filament type had relatively less influence on particle number yield (18-fold increase for ABS compared with PLA).

TVOC yield values were most influenced by Tnozzle (18-fold increase from 190 °C or 210 to 230 °C) and filament type (16-fold increase for ABS compared with PLA) and to a lesser extent, by Dnozzle (10-fold increase going from 0.4 to 0.7 mm) and device speed setting (9-fold increase from constant to slow). In a recent study, Davis et al. also observed an influence of nozzle temperature on TVOC emissions (Davis et al., 2019). All are factors related to the amount and extent of heating of the filament, which in turn releases organic vapors.

The GM size of emitted particles was most influenced by Tnozzle, i.e., increased three- to four-fold as temperature increase from 190 or 201 °C to 230 °C. To a lesser extent, GM size was influenced by filament type (two- to four-fold larger for ABS compared with PLA).

Organic vapor exposure potential from use of FFF-based toys

As shown in Table 7, TVOC emission rates ranged from about 4,400 to 5,800 μg/hr for ABS filament and from about 100 to 600 μg/hr for PLA filaments (excluding translucent blue). ANSI/CAN/UL 2904: Standard Method for Testing and Assessing Particle and Chemical Emissions from 3D Printers cites a maximum allowable TVOC emission rate of 94,700 μg/hr for occupants (adult and children) of a classroom and 3,250 μg/hr for occupants of a residential room (UL, 2019). The emission rate for extruding natural ABS filament with a single Scribbler pen would exceed this rate for a residential room, but not for a classroom.

Estimates of TVOC concentrations were calculated using Equation (1) for a classroom and residential living room. For both spaces, extruding PLA filaments with the toys resulted in TVOC concentrations that were an order of magnitude lower than when extruding natural ABS filament. From Equation (1), exposure concentration scales with the number of emitting units in a room. Hence, for the model default value of 27 students in a typical classroom, if all were using a toy 3-D pen simultaneously, the maximum estimated TVOC exposures would be 840 μg/m3 for the natural ABS filament. If three children were playing with their own toy 3-D pen simultaneously in a living room, TVOC exposure concentrations would be at most 460 μg/m3 for the ABS filament. Note that the concentration will likely be higher in the breathing zone of a child using a pen or printer if their head is in close proximity to the extruder nozzle.

Particle deposition in children’s lungs from use of FFF-based toys

Occupational exposure to FFF emissions from desktop- or larger-scale 3-D printers is associated with adverse respiratory symptoms (House et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2018). Non-occupationally exposed healthy adult volunteers who breathed in emissions from a desktop-scale 3-D printer using ABS or PLA filaments for one hour did not experience acute pulmonary inflammation (Gumperlein et al., 2018). Because no information exists on the impact of FFF-based emissions from 3-D pen and printer toys on child health, we can only speculate on such outcomes in relation to similar mixed inhalation exposures, such as air pollution. Exposure to elevated levels of ambient ultrafine PM has been associated with elevated systolic blood pressure in children (Pieters et al., 2015). Children that live closer to major roadways display smaller retinal arteriolar diameters (Provost et al., 2017), and it is attractive to speculate that microvascular dysfunction alters peripheral resistance and therefore may contribute to these elevated blood pressures. We have reported that inhalation exposure to 3-D printer emissions is associated with acute hypertension and systemic microvascular dysfunction in adult rats (Stefaniak et al., 2017). Further, we have also reported that endothelium-dependent arteriolar dilation is not fully established in juvenile rats (Nurkiewicz et al., 2004). Particle deposition modeling in the current study indicates the potential for particles emitted during use of FFF-based toys to deposit throughout the respiratory tract of children, with fractional values highest in the pulmonary region. Considered together, it is reasonable to postulate that inhalation of 3-D printer emissions impacts children to a greater extent compared with adults, because their microvascular control mechanisms are either underdeveloped and/or more sensitive to pulmonary insults. Further, effects of 3-D printer emissions may be exacerbated for children living in areas with elevated levels of ambient ultrafine PM. Future studies must directly explore these possibilities in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusions

Children are more susceptible to the effects of exposure to chemicals because their immune, pulmonary, cardiovascular and nervous systems are not fully developed. In this study, toys based on FFF technology emitted particles and organic vapors at rates comparable to those for desktop-scale 3-D printers available for use in workplaces and for home recreation. Chemicals of health interest included particles containing transition metals as well as organic vapors that are irritants (e.g., methyl methacrylate) or possible asthmagens (e.g., styrene) in adults. The metal-containing particles have sufficiently small size to permit their deposition in the alveolar region of the lung, where mechanical clearance is slow. Exposure Modeling suggests that TVOC concentrations could exceed 800 μg/m3 depending on the type of filament, number of toys in use, and room characteristics. Several factors related to the toys and consumables significantly influenced emissions. Overall, these data indicate exposure potential from use of FFF-based toys; however, future research should measure actual exposure from their use. If deemed appropriate, e.g., where multiple toys are used in a poorly ventilated area or a toy is positioned near a child’s breathing zone, control technologies should be implemented to reduce emissions and exposure risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. J. du Plessis (North-West University, South Africa) and Dr. Michael Gonzalez (U.S. EPA) for critical review of this manuscript before submission to the journal. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Government, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control, or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This research was supported by NIOSH intramural funds. This research was supported in part by an appointment of Derek Peloquin to the Post-Doctoral Research Program at the National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through Interagency Agreement No. DW-89- 92433001 between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. EPA.

Declaration of interest statement

TRN acknowledges the support of grants NIH R01 ES015022 and CPSC 1007890R. All other authors declare they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise.

References

- Asgharian B, Hofmann W, Bergmann R. 2001. Particle deposition in a multiple-path model of the human lung. Aerosol Sci Technol 34:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Azimi P, Zhao D, Pouzet C, Crain NE, Stephens B. 2016. Emissions of Ultrafine Particles and Volatile Organic Compounds from Commercially Available Desktop Three-Dimensional Printers with Multiple Filaments. Environ Sci Technol 50:1260–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAM. 2017. Test Method for the Determination of Emissions from Hardcopy Devices. St. Augustin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti N, Singh S. 2017. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printers in Libraries: Perspective and Preliminary Safety Analysis. J Chem Ed 94:879–885. [Google Scholar]

- Borak J, Fields C, Andrews LS, Pemberton MA. 2011. Methyl methacrylate and respiratory sensitization: a critical review. Crit Rev Toxicol 41:230–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC Jr., Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. 2010. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121:2331–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrley P, George BJ, Boyes WK, Rogers K. 2019. Particle emissions from fused deposition modeling 3D printers: Evaluation and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 655:395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Garciduenas L, Vincent R, Mora-Tiscareno A, Franco-Lira M, Henriquez-Roldan C, Barragan-Mejia G, Garrido-Garcia L, Camacho-Reyes L, Valencia-Salazar G, Paredes R, Romero L, Osnaya H, Villarreal-Calderon R, Torres-Jardon R, Hazucha MJ, Reed W. 2007. Elevated plasma endothelin-1 and pulmonary arterial pressure in children exposed to air pollution. Environ Health Perspect 115:1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Gimenez-Asensio MJ, Gonzalez-Alzaga B, Aguilar-Carduno C, Lorca-Marin JA, Alguacil J, Gomez-Becerra I, Gomez-Ariza JL, Garcia-Barrera T, Hernandez AF, Lopez-Flores I, Rohlman DS, Romero-Molina D, Ruiz-Perez I, Lacasana M. 2019. Childhood chromium exposure and neuropsychological development in children living in two polluted areas in southern Spain. Environ Pollut 252:1550–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan FL, House R, Kudla I, Lipszyc JC, Rajaram N, Tarlo SM. 2018. Health survey of employees regularly using 3D printers. Occup Med (Lond) 68:211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JY, Godwin C, Parker E, Robins T, Lewis T, Harbin P, Batterman S. 2014. Levels and sources of volatile organic compounds in homes of children with asthma. Indoor Air 24:403–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AY, Zhang Q, Wong JPS, Weber RJ, Black MS. 2019. Characterization of volatile organic compound emissions from consumer level material extrusion 3D printers. Build Environ 160: Article number 106209. [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Cao SJ, Chen A, Guo Y. 2016. The impact of manufacturing parameters on submicron particle emissions from a desktop 3D printer in the perspective of emission reduction. Build Environ 104:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Ng BF, Shang X, Liu H, Lu X, Wan MP. 2019. The characteristics and formation mechanisms of emissions from thermal decomposition of 3D printer polymer filaments. Sci Total Environ 692:984–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd EL, Wang J, Regens JL. 2017. Fume emissions from a low-cost 3-D printer with various filaments. J Occup Environ Hyg 14:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss O, Bianchi I, Barrero-Moreno J. 2016. Lung-deposited surface area concentration measurements in selected occupational and non-occupational environments. J Aerosol Sci 96:24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Godri Pollitt KJ, Maikawa CL, Wheeler AJ, Weichenthal S, Dobbin NA, Liu L, Goldberg MS. 2016. Trace metal exposure is associated with increased exhaled nitric oxide in asthmatic children. Environ Health 15:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumperlein I, Fischer E, Dietrich-Gumperlein G, Karrasch S, Nowak D, Jorres RA, Schierl R. 2018. Acute health effects of desktop 3D printing (fused deposition modeling) using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene and polylactic acid materials: An experimental exposure study in human volunteers. Indoor Air 28:611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessabi M, Rahbar MH, Dobrescu I, Bach MA, Kobylinska L, Bressler J, Grove ML, Loveland KA, Mihailescu I, Nedelcu MC, Moisescu MG, Matei BM, Matei CO, Rad F. 2019. Concentrations of Lead, Mercury, Arsenic, Cadmium, Manganese, and Aluminum in Blood of Romanian Children Suspected of Having Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Environ Res Pub Health 16: Article Number 2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House R, Rajaram N, Tarlo SM. 2017. Case report of asthma associated with 3D printing. Occup Med (Lond) 67:652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP. 1994. International Commission on Radiological Protection Publication 66: Human respiratory tract model for radiological protection Oxford, UK: Pergamon. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO/ASTM. 2015. ISO/ASTM 52900 Additive manufacturing — General principles — Terminology

- Keet CA, Keller JP, Peng RD. 2018. Long-Term Coarse Particulate Matter Exposure Is Associated with Asthma among Children in Medicaid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Yoon C, Ham S, Park J, Kim S, Kwon O, Tsai PJ. 2015. Emissions of Nanoparticles and Gaseous Material from 3D Printer Operation. Environ Sci Technol 49:12044–12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon O, Yoon C, Ham S, Park J, Lee J, Yoo D, Kim Y. 2017. Characterization and Control of Nanoparticle Emission during 3D Printing. Environ Sci Technol 51:10357–10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes L, Kangas A, Kukko K, Mølgaard B, Säämänen A, Kanerva T, Flores Ituarte I, Huhtiniemi M, Stockmann-Juvala H, Partanen J, Hämeri K, Eleftheriadis K, Viitanen AK. 2017. Characterization of Emissions from a Desktop 3D Printer. J Indust Ecol 21:S94–S106. [Google Scholar]

- Moscato G, Biscaldi G, Cottica D, Pugliese F, Candura S, Candura F. 1987. Occupational asthma due to styrene: two case reports. J Occup Med 29:957–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett RJ, Cox-Ganser JM, Hubbs AF, Ruder AM, Cummings KJ, Huang YT, Kreiss K. 2017. Non-malignant respiratory disease among workers in industries using styrene-A review of the evidence. Am J Ind Med 60:163–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. 2018. Volatile Organic Compounds, C1 to C10, Canister Method In: Andrews R and O’Connor PF, ed. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM) 5th Edition. Cincinnati, OH: DHHS/CDC/NIOSH. [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz TR, Boegehold MA. 2004. Calcium-independent release of endothelial nitric oxide in the arteriolar network: onset during rapid juvenile growth. Microcirculation 11:453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters N, Koppen G, Van Poppel M, De Prins S, Cox B, Dons E, Nelen V, Panis LI, Plusquin M, Schoeters G, Nawrot TS. 2015. Blood Pressure and Same-Day Exposure to Air Pollution at School: Associations with Nano-Sized to Coarse PM in Children. Environ Health Perspect 123:737–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost EB, Int Panis L, Saenen ND, Kicinski M, Louwies T, Vrijens K, De Boever P, Nawrot TS. 2017. Recent versus chronic fine particulate air pollution exposure as determinant of the retinal microvasculature in school children. Environ Res 159:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C, Gu F, Zhao P, Sharmin N, Gu H, Fu J. 2017. Capturing PM2.5 Emissions from 3D Printing via Nanofiber-based Air Filter. Sci Reports 7: Article Number 10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabile L, Scungio M, Buonanno G, Arpino F, Ficco G. 2017. Airborne particle emission of a commercial 3D printer: the effect of filament material and printing temperature. Indoor Air 27:398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, Johnson AR, du Preez S, Hammond DR, Wells JR, Ham JE, LeBouf RF, Martin SB J, Duling MG, Bowers LN, Knepp AK, de Beer DJ, dP JL. 2019. Insights into emissions and exposures from use of industrial-scale additive manufacturing machines. Safety Health Work 10:229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, Johnson AR, du Preez S, Hammond DR, Wells JR, Ham JE, LeBouf RF, Menchaca KW, Martin SB J, Duling MG, Bowers LN, Knepp AK, Su FC, de Beer DJ, dP JL. E-print. Evaluation of emissions and exposures at workplaces using desktop 3-dimensional printers. J Chem Health Safety 26:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, Bowers LN, Knepp AK, Virji MA, Birch EM, Ham JE, Wells JR, Qi C, Schwegler-Berry D, Friend S, Johnson AR, Martin SB Jr., Qian Y, LeBouf RF, Birch Q, Hammond D. 2018. Three-dimensional printing with nano-enabled filaments releases polymer particles containing carbon nanotubes into air. Indoor Air 28:840–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, LeBouf RF, Duling MG, Yi J, Abukabda AB, McBride CR, Nurkiewicz TR. 2017. Inhalation exposure to three-dimensional printer emissions stimulates acute hypertension and microvascular dysfunction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 335:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak AB, LeBouf RF, Yi J, Ham JE, Nurkewicz TR, Schwegler-Berry DE, Chen BT, Wells JR, Duling MG, Lawrence RB, Martin SB Jr, Johnson AR, Virji MA. 2017. Characterization of Chemical Contaminants Generated by a Desktop Fused Deposition Modeling 3-Dimensional Printer. J Occup Environ Hyg 14:540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinle P 2016. Characterization of emissions from a desktop 3D printer and indoor air measurements in office settings. J Occup Environ Hyg 13:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens B, Azimi P, El Orch Z, Ramos T. 2013. Ultrafine particle emissions from desktop 3D printers. Atmos Environ 79:334–339. [Google Scholar]

- UL. 2019. ANSI/CAN/UL 2904: Standard Method for Testing and Assessing Particle and Chemical Emissions from 3D Printers.

- Revised Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution and Updates to the Air Quality Index (AQI). December 14, 2012 [cited February 14, 2019]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-04/documents/2012_aqi_factsheet.pdf

- Vaisanen AJK, Hyttinen M, Ylonen S, Alonen L. 2018. Occupational exposure to gaseous and particulate contaminants originating from additive manufacturing of liquid, powdered and filament plastic materials and related post-processes. J Occup Environ Hyg 16:258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance ME, Pegues V, Van Montfrans S, Leng W, Marr LC. 2017. Aerosol Emissions from Fuse-Deposition Modeling 3D Printers in a Chamber and in Real Indoor Environments. Environ Sci Technol 51:9516–9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyper GMA, Grant I, Fletcher E, McCartney G, Stockton DL. 2019. The impact of worldwide, national and sub-national severity distributions in Burden of Disease studies: A case study of cancers in Scotland. PLoS ONE 14:e0221026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J, LeBouf RF, Duling MG, Nurkiewicz TR, Chen BT, Schwegler-Berry D, Virji MA, Stefaniak AB. 2016. Emission of particulate matter from a desktop three-dimensional (3-D) printer. J Toxicol Environ Health A 79:453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wong JPS, Davis AY, Black MS, Weber RJ. 2017. Characterization of particle emissions from consumer fused deposition modeling 3D printers. Aerosol Sci Technol 51:1275–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Zontek TL, Ogle BR, Jankovic JT, Hollenbeck SM. 2017. An exposure assessment of desktop 3D printing. J Chem Health Safety 24:15–25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.