Abstract

Objective:

To test the feasibility of a university health center-delivered smoking cessation intervention that adds a 6–week course of text messaging to brief advice and nicotine patch therapy.

Participants:

Young adult cigarette smokers (n=40) from 2 universities from January 2015-May 2016.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trial comparing brief advice, nicotine patch therapy and: 1) a 6-week text messaging intervention (n=20); or 2) no text messaging (n=20). Primary outcomes included enrollment, retention and satisfaction.

Results:

Forty participants enrolled (38% of those screened). Retention rates were 98% and 92.5% at 6- and 12-weeks. Of those who completed the text intervention (n=16), 64.3% felt the texts were “helpful”, however they reported desire for tailoring and concern that texts triggered smoking. Biochemically-confirmed abstinence rates did not significantly differ between text and control arms.

Conclusions:

These feasibility data suggest that text messaging may need to be modified to better engage and motivate college-age smokers.

Keywords: Young Adult, Smoking Cessation, Mobile health

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is a pervasive public health problem and is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States.1 Despite great advances in tobacco control, about 11% of young adults ages 18 to 24 are current smokers.2,3 Most young adult smokers want to quit (62%−90%),4,5 however cessation rates in this population are approximately 10%.5 Young adults, and college students in particular, have been challenging to engage in traditional smoking cessation treatments, suggesting the need for new smoking cessation delivery systems.6

Text messaging is a highly preferred form of communication among young adults, and has an established and robust body of evidence supporting its efficacy in smoking cessation.7–9 For example, a 2016 meta-analysis of 22 interventions across 10 countries (n=15,593 participants) found that smokers who received text messaging interventions were more likely to abstain from smoking and reduce cigarette consumption.7 Additionally, several studies have applied texting for smoking cessation in young adults.10,11 The 3-month Text2Quit program (with tailored text messages and emails) has been found to be acceptable and utilized by college students.10 A randomized controlled trial of 1,589 young adult college and university students in Sweden found that a 12-week text messaging intervention, compared to twice monthly texts thanking participants for study participation, increased the odds of self-reported abstinence of at least 8 weeks at the four-month follow-up (OR 2.05; 95% CI 1.57–2.67).12 Ybarra et al. also demonstrated that young adult smokers in the Stop My Smoking USA text messaging program, compared to the attention-matched control group, had increased the odds of self-reported abstinence at 4-weeks (OR 3.33; 95% CI 1.58–7.45).11

Although these studies have demonstrated the efficacy of text messaging for smoking cessation in young adult college students, and studies have established the efficacy of text messaging as an adjunct to health advice or the Quitline for smoking cessation in adults,13 the current study adds to the scientific evidence by testing whether, among college students, text messaging can boost the treatment effect of brief advice by a healthcare provider and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) as recommended by the 2008 Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical practice Guideline.14 Importantly, the American College Health Association recommends that colleges offer non-cost-prohibitive smoking cessation interventions, including medications, for the treatment of all student smokers.15 Meta-analyses of clinical trials have shown that all forms of nicotine replacement therapy increase the rate of smoking cessation over unaided quitting by 50%–60%.16 Brief advice (less than 10 minutes) alone by a medical provider increases 12-month abstinence from a baseline of 2–3% to about 5%.17

Thus, this pilot study aims to test the feasibility of a cigarette smoking cessation intervention delivered in university health centers that combines brief advice, NRT (i.e. nicotine patch therapy), and a 6-week course of text messaging for young adult college students. We report initial feasibility of this intervention and provide preliminary descriptions of biochemically confirmed cigarette smoking abstinence at 6- and 12-week follow-up. This pilot study adds to the literature by exploring whether text messaging programs are acceptable to college students when paired with brief advice and NRT, and whether text messaging potentially boosts the effect of smoking cessation treatment.

METHODS

We conducted a randomized controlled pilot trial of 40 cigarette smokers between January 2015 and May 2016. Participants were randomized to either 1) A 6-week text messaging smoking cessation intervention, brief physician advice and a 6-week course of nicotine patch therapy (n=20); or 2) brief physician advice and a 6-week course of nicotine patch therapy alone (Standard of care; n=20) (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02191033). Study procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment Procedures

College students were recruited from 1 private and 1 public university in the Northeast. Recruitment efforts included flyers and paid Facebook advertisement campaigns conducted between from January 2015-May 2016 targeting students at the two universities, advertisements in the school newspapers, online postings on the study website, and e-mails to student groups that were sent by the research partners at each school. Study advertisements stated: “Do you want to quit smoking? Play an important role in research by volunteering for this free and confidential study.” Research assistants also conducted in-person recruitment events on campus and kept detailed logs of the number of people they screened for eligibility during the in-person recruitment events. Advertisements and flyers allowed students to either call a phone number to complete screening activities, complete the screening via text message, or complete a secure, confidential online survey to assess eligibility. A research assistant contacted eligible students via phone to further describe the study and to set up in in-person intake interview.

Participants

Potentially eligible students met the research assistant at the university health center for an intake interview. We focused this intervention on current smokers (defined as smokers who have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and now smoke every day or some days every week), rather than daily smokers, as these smokers are more representative of the population of young adult cigarette smokers.18,19 Eligibility criteria included: age 18 through 24 years, self-report of being a current cigarette smoker (as defined above), enrolled as a full/part time student at the university, English-speaking, interested in quitting smoking, having a cell phone for personal use with an unlimited text messaging plan, and able to attend follow-up appointments at 6- and 12-weeks at a public location on/near campus. Exclusion criteria included: self-report history of hypersensitivity/allergy to nicotine patch, serious arrhythmias, or history of heart disease (confirmed by medical provider during study visit), or current pregnancy/breastfeeding/plan for pregnancy (by self-report and confirmed by pregnancy test and medical provider during study visit). After providing written consent, participants were assigned by block randomization to one of two groups, text or control. Block size was 10 and random sequence was generated via an online randomization software (randomization.com). Once the randomization sequence was generated, it was contained in sealed opaque envelopes, which were opened by the research assistant after enrollment. Participants were then assigned to the treatment group contained within the envelope. Participants were compensated for their time with $20 cash for the baseline, 6-, and 12-week follow-up visits, for a total possible remuneration of $60/participant.

Intervention Components

Brief Advice:

After enrolling, participants immediately met with a medical provider in the university health center to receive brief smoking cessation advice consistent with the Public Health Service 5A paradigm of Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist and Arrange for follow-up.14 This guideline is a widely endorsed framework for medical provider brief advice and is the standard of care for brief treatment of smokers seen in primary care. The 5A method encourages providers to Ask all patients about tobacco use, Advise them to quit smoking, Assess their willingness to quit, Assist them in their quit effort (by prescribing evidence-based pharmacotherapies such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) when indicated) and Arrange for follow-up services.

The brief advice intervention was delivered by the university health center’s physician or nurse. These providers were trained by the principal investigator with a 1-hour role play and didactic session to ensure standardization of the 5A counseling. Providers used a standardized checklist to deliver the 5A and nicotine patch counseling to participants and ensure fidelity of the counseling intervention. For the purpose of the study intervention, the providers instructed participants to set a quit date within the next 3 days.

Nicotine Patch:

Only those participants who smoked ≥5 cigarettes per day received nicotine patch counseling (information about how to use NRT, potential adverse events, how to respond to events), and a 6-week open-label supply of 14 mg (for those smoking 5–9 cigarettes/day) or 21 mg (for those smoking ≥10 cigarettes/day) nicotine patch therapy during the visit to minimize economic barriers.

Text messaging intervention:

Participants randomized to the text messaging arm then enrolled in the National Cancer Institute’s SmokeFreeTXT program via the public website www.smokefree.gov.20 During the study visit, the research assistant had the participant enter his/her mobile phone number, gender, smoking frequency and quit day into the online enrollment form and confirmed that the participant received the welcome message prior to the end of the in-person study visit. In brief, SmokeFreeTXT text messaging program is a free, fully-automated text message-based program designed to deliver 6-weeks of motivational and fact-based information via unidirectional and interactive bidirectional text messages after a smoker sets a quit date.20,21 Launched in 2011, the SmokeFreeTXT text messaging library uses over 35 behavior change techniques to enhance motivation and self-regulation.20

Text messages assessing mood, craving, and smoking status were sent to participants up to five times a day, and the user received messages back based on the responses they submitted. In addition, users could send the system one of three programmed keywords (CRAVE, MOOD, and SLIP) and the system sent one of 10 unique, automated responses based on the texted keyword. Users were instructed that they could text STOP to discontinue the service.

Measures

Measures for this study were collected during the baseline, 6- and 12-week follow-up visits. The primary feasibility outcomes included enrollment and retention in the intervention at 6- and 12-weeks and satisfaction with the text messaging intervention at 6-week follow-up. We also assessed treatment outcomes of 6- and 12-week 7-day point prevalence of biochemically- verified tobacco abstinence rates.

Baseline assessments included demographics, 28-day Time Line Follow Back interview to assess cigarettes smoked/day and number of days smoked in past month, the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence,22 The Ladder of Contemplation,23 The Smoking Self Efficacy Questionnaire24 and the Wisconsin Predicting Patients’ Relapse Questionnaire (WI-PREPARE).25 We also measured participants’ reports of mobile phone and social media use at baseline.

Acceptability and Feasibility

Participants assigned to the intervention arm completed a semi-structured in-depth individual in-person interview at the 6-week follow-up visit to assess satisfaction. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Using questions modified from previous studies of text messaging,10 these participants also completed a survey to rate via a 5-point Likert Scale (‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’); how much they liked the frequency and content of the text messages, how helpful they found the messages in supporting a quit attempt, and whether they would recommend the program to a friend. Program engagement was also measured by asking participants how many of the texts they read (none, some, most, all), and by asking participants to quantify how often they replied to the texts (never, sometimes, most of the time, always).

Cigarette Smoking-Related Secondary Outcomes

Smoking was measured by assessing 7-day biochemically confirmed point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at the 6- and 12-week follow-up, defined as a self-report of no smoking in the past 7 days and a breath CO level of <10 ppm. Other outcomes assessed at 6- and 12-week follow-up included cigarettes smoked per day measured via 28-day time-line follow back. The study staff were not blinded to group assignment when assessing study outcomes. To assess for use of other tobacco products to assist with smoking reduction/cessation, at the 6- and 12-week follow-up we asked “Did you use any of the following tobacco products to help you quit smoking during the past 6 weeks?” with yes/no response options: [E-cigarettes, snus, dissolvable, some other new tobacco product]. The 12-week follow-up survey also asked participants which additional cessation aids/supports they had used since their quit attempt with yes/no response options: [‘Text messaging program other than SmokeFreeTXT’, ‘Smoking cessation app’, ‘Telephone Quitline’, ‘One on one counseling’, ‘A stop smoking clinic, class or support group’, ‘Help or support from family/friends’, ‘Another internet/web-based program’, ‘Books, pamphlets, videos, other materials’, ‘Acupuncture’, ‘Hypnosis’, ‘Other’).

Analysis

For the primary outcomes of enrollment and retention, study staff monitored the number of students 1) asked to participate; 2) who consented; 3) who were retained at the 6- and 12-week follow-up visits. Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics and smoking behaviors were calculated. The primary outcome of participant satisfaction was assessed via Likert scales and qualitative data analysis of transcribed interviews. Transcribed interviews were deidentified and entered into NVIVO (version 11) software. Data were analyzed via directed content analysis by two study investigators to identify emergent themes.

For the exploratory smoking-related secondary outcomes, differences between smoking outcomes at 6- and 12-weeks were compared with an intention to treat analysis with chi-square tests. Smokers lost to follow-up were imputed to be smoking. Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). Alpha was set at 0.05. Given the small sample size, multivariable modeling was not performed.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Retention:

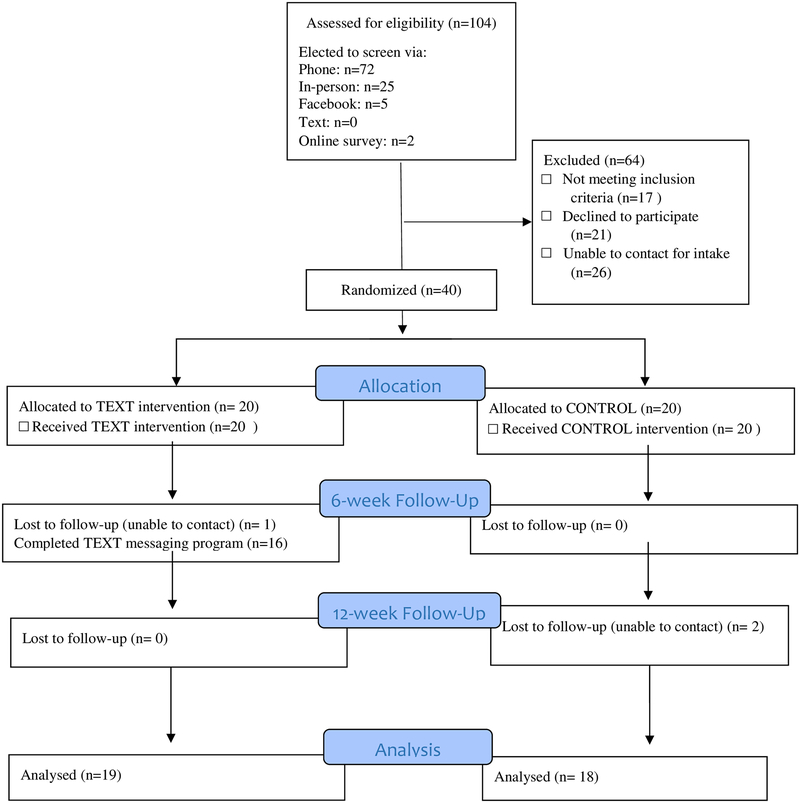

Through in-person recruitment events, flyers, online advertisements and emails, we screened 104 smokers for eligibility (n=72 via phone, n=25 in-person, n=5 via Facebook advertisements linked to online surveys, n=2 via online surveys), of whom 44 were eligible (Figure 1). Of those eligible, 40 participants enrolled in the study [38% (40/104)], and we randomized 20 participants to the intervention group and 20 participants to the control group. Retention rates at 6- and 12-weeks post-enrollment were 98% (39/40) and 92.5% (37/40) respectively; retention rates were not statistically different between groups. Of participants randomized to the text messaging arm, 75% (16/20) completed the 6-week course of text messages (vs. stopping the texts).

Figure 1:

Consort Diagram

Participant Characteristics

Most participants were female, white, and non-Hispanic students with full-time status and a mean age of 20.2 years (Table1). The majority of the sample had private health insurance. At baseline, participants smoked a mean of 8.3 cigarettes per day; 82.5% were daily smokers. A majority of the participants reported ≥ 5 cigarettes/day and received the open-label supply of NRT. Most participants reported using an e-cigarette at least once in the past 30 days at baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in breath carbon monoxide levels or WI-PREPARE scores between groups, however participants in the control arm reported higher smoking self-efficacy score. At baseline, participants reported sending a median of 50 text messages per day.

Table 1:

Sample Characteristics and Demographics (n=40)

| Characteristics | Treatment Arm | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text (n=20) | Control (n=20) | (N=40) | |

| Age, mean [SD], years | 19.9 [1.7] | 20.5 [1.5] | 20.2 [1.6] |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (65) | 9 (45) | 22 (55) |

| Male | 7 (35) | 11 (55) | 18 (45) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (10) | 0 | 2 (5) |

| Missing | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Asian | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (2.5) |

| Black or African American | 2 (10) | 0 | 2 (5) |

| White or Caucasian | 17(85) | 19 (95) | 36 (90) |

| College Year, n (%) | |||

| Freshman | 7(35) | 1(5) | 8 (20) |

| Sophomore | 5(25) | 8(40) | 13 (32.5) |

| Junior | 3(15) | 5(25) | 8 (20) |

| Senior | 5(25) | 6(30) | 11 (27.5) |

| Status, n (%) | |||

| Full Time | 18(90) | 20(100) | 38 (95) |

| Part Time | 2(10) | 0 | 2 (5) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |||

| Military/CHAMPUS/VA | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Private insurance from your parent | 15 (75) | 17 (85) | 32 (80) |

| Public insurance (Medicaid) | 5 (25) | 2 (10) | 7 (17.5) |

| Tobacco Use Behaviors | |||

| Daily Smoker, n (%) | 18 (90) | 15 (75) | 33 (82.5) |

| Cigarettes smoked/day, mean [SD] | 7.1 [4.6] | 7.5 [4.3] | 7.3 [4.4] |

| Smoked ≥ 5 cigarettes/day, n (%)a | 14 (70) | 15 (75) | 29 (72.5) |

| Age Started Smoking cigarettes daily mean [SD] | 16.1 [1.6] | 17 [1.8] | 16.5 [1.7] |

| FTND Score, mean [SD] | 2.9 [1.7] | 3.1 [1.9] | 2.9 [1.7] |

| Breath Carbon Monoxide Level, parts per million, mean [SD] | 9.4 [7.9] | 7.3 [5.3] | 8.3 [6.7] |

| Used E-cigarette in past month, n (%) | 14 (70) | 15 (75) | 29 (72.5) |

| Used Cigar/Cigarillo in past month, n (%) | 5 (25) | 9 (45) | 14 (35) |

| Used Hookah in past month, n (%) | 10 (50) | 6 (30) | 16 (40) |

| Used Marijuana in past month, n (%) | 13 (65) | 14 (70) | 27 (67.5) |

| Smoking Cessation Behaviors | |||

| Number of Previous Quit Attempts, median [range] | 2 [0–10] | 2 [0–10] | 2 [0–10] |

| Level of Motivation to Quit, median [range]b | 8 [3–10] | 8.5 [6–10] | 8 [3–10] |

| Smoking Self Efficacy Score, mean [SD]c. | 2.1 [0.7] | 2.4 [0.8] | 2.2 [0.5] |

| WI-PREPARE score, mean [SD] | 5.2 [1.5] | 4.6 [1.4] | 4.8 [1.5] |

These participants received an open-label supply of NRT during the study.

As measured by the Contemplation Ladder,23 a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation with 10 indicating a high and 0 indicating a low level of readiness to quit..

As measured by the Smoking Self Efficacy Questionnaire,24 a measure of self-efficacy for resisting the urge to smoke.

Satisfaction with text messaging

Findings from the satisfaction surveys demonstrated that almost two-thirds of the 16 participants who completed the text messaging program felt it was helpful, while just over half felt that the messages were tailored to college students (Table 2). More participants felt that the texts helped with preparing to quit, and their quit day, than with the first week after their quit date. Fifty percent of participants felt that the number of texts was just right, however 38% felt there were too many.

Table 2:

Satisfaction with text messaging program (n=16)a

| %b | |

|---|---|

| Agree/Strongly Agree: | |

| The texts came at the right time of day | 50 |

| I liked the content of the text messages | 57 |

| All of the texts were written specifically for college students | 57 |

| The text messages were helpful in getting me to TRY to quit | 64 |

| I would recommend the texts to a friend | 64 |

| Texts were helpful/very helpful: | |

| For getting ready to quit | 50 |

| On your quit date | 57 |

| For getting through the first week after your quit date | 50 |

| Not at all concerned about privacy? | 86 |

| Proportion of texts read | |

| All | 31 |

| ~75% | 44 |

| < 50%% | 25 |

| Self-report of proportion of texts replied to | |

| Often | 6 |

| Sometimes | 44 |

| Rarely | 44 |

| Never | 6 |

| Satisfaction with volume of texts | |

| Just Right | 50 |

| Too Many | 38 |

| Too Few | 12 |

Among participants randomized to the text messaging arm who completed 6-weeks of text messaging.

Percentages rounded to nearest whole number

Findings from the in-depth individual interviews demonstrated that participants were satisfied with several aspects of the text messages: Reminders of Intrinsic Motivation, Supportive content, and the Frequency (See Table 3). Participants felt that the text messages helped bolster their internal motivation to quit and reminded them that they had set a quit day: “It was just like a constant reminder of like I could do it…It was just a constant reminder of why you wanted to and why it would be good to” (#148). Many participants shared how their friends and coworkers continued to smoke as they were making a quit attempt. They found the text messages that gave tips about how to overcome the social triggers to smoke to be particularly salient and helpful: “They kind of gave me advice as to how, um to deal with the social aspect of quitting, even if you have friends that still smoke social, friends and family smoking were the most helpful. (#128) Participants also reported that the distraction techniques, such as reminders to breathe or exercise during cravings helped get their “mind off of it”.

Table 3:

Satisfaction with Text Messaging: Qualitative Data

| Overall Theme | Participant Quotations | |

|---|---|---|

| Helpful aspects of Program | ||

| Reminder of Intrinsic Motivation | It just like reminds you that you’re kind of like already committed to it. Smoker (#144) They reminded me that at one point I, I said I wanted to quit. (#128) |

|

| Support with social triggers | So I don’t have like a huge network of people to talk to. Well I think it’s safe to say like all but one or two of my friends are smokers. Um, so what it did for me is, kind of help me think twice about it. So instead of just saying yes every time, like I’ll be like, ‘no I’ll pass this time. (120) Um, because the program is like on your side to quit. And it’s harder to talk to your friends about it sometimes when one, they smoke or they’re just not supportive or as supportive So it was like someone that understood (132) |

|

| Distraction techniques during cravings | Well one idea was like exercising. And I started doing that and it did get my mind off of it. And then another one was, just waiting until the craving like, what was it? It was like, ‘try to find something to do,’ so you can like wait instead of going outside, I don’t know. (148) I mean before I like stopped them I remember it was just like ‘oh do some,’ like, ‘chew gum.’ ‘Do some kind of breathing exercises.’ Like remember, remind yourself like why you made, why am I doing this, I don’t need to do this. All that stuff. So I mean I guess the ideas were good …(146) I should like ‘to take like a breather,’ if I get stressed. Or ‘go outside and just um, just calm down a little bit,’ and try to ‘do something small and go back inside,’ and then retackle the situation and stuff like that. That was a good one. (116) |

|

| Not helpful | ||

| Lack of relevance to college students | I, I don’t read them and say like ‘alright these are aimed at college kids,’ but…Um, just texts about being active and ‘stay strong, positive attitude.’ That’s a younger type of thing. Then there’s other ones that say ‘Been putting off a home improvement project.’ (120) | |

| Texts as trigger to smoke | They remind me, they remind me more of smoking than of not smoking. (122) | |

| Recommendations | ||

| Focus on age-relevant motivators | But it didn’t, um, like the main reason I wanted to and most teenagers isn’t because of health. Um, either because of money or the whole feeling of being addicted to something or needing something. (147) | |

| Tailoring | Timing: It depends on the person’s schedule. Maybe find out what the students’ schedule is, you know? Like if they have early classes then the seven, nine am texts would be fine. (120) | |

Participants also discussed aspects of the text messaging program that they felt were not helpful. They felt the text messages were generic and some of the messages not relevant to college students: “But I didn’t like that they weren’t specific to someone my age. I mean they talked about going on a hike or something like that and someone my age doesn’t want to go on a hike ya know, they just want to hang out with their friends or something” (#122). Some participants also discussed how receiving the texts bolstered their cravings and served as a reminder to smoke. The most common recommendations for improvement therefore included altering the content of the text messages so they focused on age-relevant motivators and tailoring the timing so it fit with the college student schedule.

Cigarette Smoking-Related Secondary Outcomes

At the 6-week follow-up, 15% of the participants in the text messaging arm and 25% of those in the control arm demonstrated biochemically confirmed cigarette smoking abstinence (Table 4). At 12-week follow-up, abstinence rates in both groups fell to 5%. Data from the 28-day timeline follow-back demonstrated that the total number of cigarettes smoked in the past 28 days dropped significantly from baseline at the 6-week and 12-week follow-up visits. However, there were no statistically significant differences between text and control arms in total number of cigarettes smoked/day from baseline to 6- week or baseline to 12-week follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Smoking-related outcomes

| 6-weeks | 12-weeks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text, n=20 | Control, n=20 | p-value | Text, n=20 | Control, n=20 | p-value | |

| Biochemically confirmed 7-day PPA, n (%)a | 3 (15) | 5 (25) | 0.6 | 5 (25) | 6 (30) | 0.7 |

| Cigarettes smoked/day, mean [SD] | 2.5 [2.4] | 2.0 [3.6] | 0.09 | 2.7 [2.9] | 2.6 [3.7] | 0.3 |

| Change in cigarette per day from baseline, mean [SD] | −4.8 [0.7] | −5.2 [0.7] | 0.7 | −4.7[0.8] | −4.6 [0.8] | 0.9 |

PPA= point prevalence abstinence; missing data were imputed to indicate smoking

Of the participants who completed the 6-week follow-up, 3/19 (16%) in the text arm, and 9/20 (45%) in the control arm reported using an e-cigarette to help them quit smoking during the past 6-weeks. At the 12-week follow-up 5/19 (26.3%) in the text arm and 7/18 (38.8%) in the control arm reported using an e-cigarette to help them quit smoking. Participants who completed the 12-week follow-up most commonly reported speaking with family/friends as a smoking cessation support (10/19 text and 8/18 control). A small proportion reported using other cessation aids/supports, such as applications, web-based programs, or books (2/19 text vs. 4/18 control).

DISCUSSION

This pilot study suggests that it is feasible to combine text messaging with college health physician-delivered brief advice and nicotine patch therapy in young adult college students, as evidenced by the high retention rate in the study, reports of text messaging engagement (i.e. 75% of participants reading 75% or more of the texts) and that many participants would recommend text messaging for a friend. However, there is evidence that the intervention could be improved for this population, as many young adult smokers also felt the content of the text messaging could be improved, reported low levels of responding to texts, and preliminary examination of smoking-related outcomes revealed no significant differences between groups. Whereas previous studies examining young adult smokers have focused on stand-alone text messaging programs this study is unique in that it tests whether text messaging may supplement in-person evidence-based smoking cessation treatment delivered within university health centers.

The qualitative findings suggest several mechanisms by which text messages may help support a brief intervention and NRT-supported quit attempt. Most participants reported that the quantity of messages sent was appropriate and that they were able to read the text messages. The in-depth interviews demonstrated that participants found that the text messages helped provide reminders of their internal motivation to quit smoking. This finding suggests that text messaging may help sustain the effects of assessing one’s motivation to quit during the brief advice session. It also builds upon previous research that has shown that improving self-efficacy is a key component of text messaging smoking cessation interventions.26,27 Participants also found that the text messaging content that focused on distraction techniques for cravings was helpful, and felt that the content provided support around social triggers to smoke.

Nonetheless, although this preliminary evidence demonstrates that it is feasible to enroll college students in an intervention that combines guideline-based brief advice and NRT with text messaging, it also suggests that there may not be significant benefit to adding text messaging to standard of care smoking cessation treatments offered in university health centers. Although this pilot study was not sufficiently powered to formally test differences in smoking-related outcomes, there were no significant differences between groups on smoking-related outcomes. There are several factors which may explain the lack of difference in the randomized groups. First, the text messaging participants suggested a desire for increased tailoring of the text messages, specifically stating that the content felt that it was not written for college students specifically. A randomized controlled trial of tailored vs. non-tailored emails found greater tailored content was associated with greater abstinence rates and greater use of non-medication cessation aids, therefore suggesting that a greater treatment effect might have been found if the text messaging program was highly tailored for college students.28 Further, participants also felt that the frequent text messages may have served as a trigger to smoke, which may have explained why the abstinence rates were lower in the text messaging arm than the control arm. Future studies are needed to determine whether text messages do, in fact, serve as a trigger to smoke, and whether timing and frequency may mitigate this potential effect. Second, similar to previous text messaging studies, a substantial proportion of those randomized to the text messaging arm were unable to receive text messages (25%) via the automated system, despite being enrolled in the presence of the research assistant, suggesting that technical difficulties may have resulted in an underestimation of treatment effect. Future studies may need to include this potential for technical difficulties with text messaging in their research design in order to ensure adequate power. Third, given previous work that has shown that text messages do not confer additional benefit to multi-modal Quitline services,29 it is possible that text messaging treatments do not add benefit to standardized medical advice, and instead may be better targeted towards the majority of young adult smokers who do not access evidence-based medical treatments for smoking cessation. It is also possible that greater use of e-cigarettes in the control arm than the text arm may have contributed to the lack of difference in smoking cessation rates between groups, however it is currently unknown whether e-cigarettes serve as an effective smoking cessation aid. Lastly, it is also plausible that, despite young adults’ preference to not receive more text messages, that the dosage of text messages was not optimal to see a treatment benefit above and beyond medical advice. Nonetheless, this pilot study was not powered to detect differences in smoking-related outcomes, and future research is needed to fully test these hypotheses.

This study has several limitations. The findings may not generalize to all college smokers as we only recruited from two universities in one geographic area. Given that this was a pilot study, the outcome assessors were not blinded to group assignment. We used self-report measures of text messaging engagements, and cannot accurately estimate whether the level of interaction with the text messaging program was associated with study outcomes. Lastly, as noted above, the text messaging program experienced technical problems during the study period, which may have minimized the effect of the intervention.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that that it is feasible to combine a text messaging program with college health physician-delivered brief advice and nicotine patch therapy in young adult students, as evidenced by the high retention rate in the study, and the general acceptability of text messaging content acceptability. However, these data also suggest that text messaging programs may need to be modified to better engage and motivate college-age smokers who participate in evidence-based smoking cessation treatments, such as brief advice and NRT. Future research is needed to continue to refine text messaging interventions to meet the needs of college-age smokers, and to determine how they may help augment existing evidence-based tobacco use disorder treatment practices.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the staff of the university health centers who participated in this study, Lindsey Behlman for her assistance with data collection, and the Yale Center for Analytical Sciences for data analysis support.

This study was supported by K12DA033012, CTSA grants UL1 TR000142, and KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. The funders had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2014;17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225–1232. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53–59. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watkins SL, Thrul J, Max W, et al. Cold Turkey and Hot Vapes? A national study of young adult cigarette cessation strategies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018; 10.1093/ntr/nty270. 10.1093/ntr/nty270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, et al. Quitting Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–1464. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler KM, Fallin A, Ridner SL. Evidence-based smoking cessation for college students. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(1):21–30. 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott-Sheldon LA, Lantini R, Jennings EG, et al. Text Messaging-Based Interventions for Smoking Cessation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e49. 10.2196/mhealth.5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, et al. Efficacy of SMS Text Message Interventions for Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1–10. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do HP, Tran BX, Le Pham Q, et al. Which eHealth interventions are most effective for smoking cessation? A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2065–2084. 10.2147/PPA.S169397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abroms LC, Ahuja M, Kodl Y, et al. Text2Quit: Results from a pilot test of a personalized, interactive mobile health smoking cessation program. J Health Commun. 2012;17(SUPPL. 1):44–53. 10.1080/10810730.2011.649159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ybarra ML, Holtrop JS, Prescott TL, et al. Pilot RCT results of stop my smoking USA: a text messaging-based smoking cessation program for young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1388–1399. 10.1093/ntr/nts339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mussener U, Bendtsen M, Karlsson N, et al. Effectiveness of Short Message Service Text-Based Smoking Cessation Intervention Among University Students: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(3):321–328. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobos-Campos R, Apinaniz Fernandez de Larrinoa A, Saez de Lafuente Morinigo A, et al. Effectiveness of Text Messaging as an Adjuvant to Health Advice in Smoking Cessation Programs in Primary Care. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(8):901–907. 10.1093/ntr/ntw300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Services; May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College Health Association. Position statement on tobacco on college and university campuses. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(3):266–267. 10.1080/07448481.2012.660440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD000146. 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4(5):CD000165. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Sung HY, Yao T, et al. Infrequent and Frequent Nondaily Smokers and Daily Smokers: Their Characteristics and Other Tobacco Use Patterns. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(6):741–748. 10.1093/ntr/ntx038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinsker EA, Berg CJ, Nehl EJ, et al. Intent to quit among daily and non-daily college student smokers. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(2):313–325. 10.1093/her/cys116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Augustson E, Cole-Lewis H, Sanders A, et al. Analysing user-reported data for enhancement of SmokefreeTXT: a national text message smoking cessation intervention. Tob Control. 2017;26(6):683–689. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Text4Health Projects. 2014; http://www.hhs.gov/open/initiatives/mhealth/projects.html. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- 22.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10(5):360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colletti G, Supnick JA, Payne TJ. The Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (Sseq) - Preliminary Scale Development and Validation. Behavioral Assessment. 1985;7(3):249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolt DM, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, et al. The Wisconsin Predicting Patients’ Relapse questionnaire. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):481–492. 10.1093/ntr/ntp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Abroms LC. How do text-messaging smoking cessation interventions confer benefit? A multiple mediation analysis of Text2Quit. Addiction. 2017;112(4):673–682. 10.1111/add.13685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham AL, Papandonatos GD, Cobb CO, et al. Internet and Telephone Treatment for smoking cessation: mediators and moderators of short-term abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(3):299–308. 10.1093/ntr/ntu144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westmaas JL, Bontemps-Jones J, Hendricks PS, et al. Randomised controlled trial of stand-alone tailored emails for smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):136–146. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boal AL, Abroms LC, Simmens S, et al. Combined Quitline Counseling and Text Messaging for Smoking Cessation: A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1046–1053. 10.1093/ntr/ntv249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]