Abstract

Objectives:

Research has enhanced our understanding of opioid misuse prevalence and consequences, but few studies have examined recovery from opioid problems. Estimating national recovery prevalence and characterizing individuals who have resolved opioid problems can inform policy and clinical approaches to address opioid misuse.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional investigation of a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults who reported opioid problem resolution (OPI). For reference, OPI were compared to an alcohol problem resolution group (ALC). Analyses estimated OPI/ALC prevalence, differences in treatment/recovery service use and psychological well-being, within two recovery windows: <1 year (early-recovery) and 1–5 years (mid-recovery) since OPI/ALC problem resolution.

Results:

Of those who reported AOD problem resolution, weighted problem resolution prevalence was 5.3% for opioids (early-recovery=1.2%, mid-recovery=2.2%) and 51.2% for alcohol (early-recovery=7.0%, mid-recovery=11.5%). In mid-recovery, lifetime use of formal treatment, pharmacotherapy, recovery support services, mutual-help, and current pharmacotherapy were more prevalent in OPI than ALC. Service utilization did not differ between early-recovery OPI and ALC. Common services used by OPI included inpatient treatment (37.8%) and state/local recovery organizations (24.4%) in mid-recovery; outpatient treatment (25.7%) and recovery community centers (27.2%) in early-recovery; Narcotics Anonymous (40.2―57.8%) and buprenorphine-naloxone (15.3―26.7%) in both recovery cohorts. Regarding well-being, OPI reported higher self-esteem than ALC in early-recovery, and lower self-esteem than ALC in mid-recovery.

Conclusions:

An estimated 1.2 million American adults report resolving an opioid problem. Given the service use outcomes and longer-term problem resolution of mid-recovery OPI, early-recovery OPI may require encouragement to utilize additional or more intensive services to achieve longer-term recovery. OPI beyond recovery-year one may need enhanced support to address deficient self-esteem and promote well-being.

Keywords: Recovery, Opioids, Prevalence, Pathways, Well-Being

Introduction

Opioid misuse and related problems constitute one of the most devastating public health crises in modern times. In 2017, approximately 11.4 million Americans reported past-year heroin or prescription pain reliever misuse (SAMHSA, 2018). Although less than 20% of these individuals meet formal criteria for a past-year opioid use disorder (SAMHSA, 2018), opioid misuse itself poses life-threatening risk to individuals (e.g., compromised mental/physical health, transmission of infectious disease) and substantial economic burden to society (loss of productivity, increased crime). Most notably, opioid-attributable overdose deaths have reached epidemic proportions. Over 42,000 overdose deaths occurred in 2016, rates five times higher than those reported in 1999 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). The gravity of the consequences of opioid misuse emphasize the import of better understanding its nature in order to help individuals reduce and cease their use, and prevent others from initiating use.

While investigative efforts to-date have largely focused on characterizing the prevalence of opioid misuse, its harmful consequences, and its burden to individuals and society at large, there is a dearth of literature addressing recovery from opioid use problems. Despite a general lack of data concerning the ways in which individuals resolve substance use problems, investigations conducted to-date have largely focused on alcohol (e.g., Dawson et al., 2006, 2007; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). Moreover, a substantial proportion of this literature has examined problem resolution in the context of a treatment setting (Gossop et al., 2002; Dobkin et al., 2002; Adamson et al., 2009). Though treatment-focused research offers important insight to recovery pathways, only 7.5% of American adults with a past-year substance use disorder receive treatment (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017). Epidemiological studies suggest that a significant number of people can achieve remission (12 months symptoms free) of DSM-IV alcohol dependence without the use of clinical treatment or recovery services (Dawson et al., 2006, 2007; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). Substantially fewer publications address other drug use disorders, but those that have report smaller proportions of individuals achieving remission without some kind of service utilization (McCabe et al., 2016). Most notably, the best evidence there is currently for treating opioid use problems is with pharmacological approaches such as buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone (Mattick et al., 2014; Scott et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2018). Still, national probability-based estimates of problem resolution that pertain specifically to opioids are lacking. Greater characterization of individuals who have resolved problematic opioid use, particularly non-treatment seeking individuals, is necessary to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the U.S. opioid epidemic and how it can best be addressed. Characterizing these individuals and their problem resolution pathways can provide insight into the types of clinical and psychosocial resources contributing to problem resolution, guide our understanding of recovery trajectories, and inform approaches to effectively and efficiently address opioid misuse problems.

The current study aims to address this gap in the literature. Using data from the first national probability-based sample of U.S. adults who have resolved a significant alcohol or drug (AOD) use problem, we estimated the national prevalence of opioid problem resolution and examined service utilization and indices of psychological well-being in individuals who resolved a primary opioid use problem (OPI). To contextualize our findings, we compared OPI to those who have resolved a primary alcohol use problem (ALC), as ALC have been characterized more extensively and comprehensively. Importantly, it may take up to five years of continuous remission before the risk of becoming symptomatic for a substance use disorder (SUD) in the following year drops to the same level as the general population (<15%; White, 2012). Thus, recovery durations of five years or less are critical time horizons associated with continued vulnerability that have particular clinical and public health significance (White, 2008; Kelly et al., 2018). The first year of recovery is an especially critical period, with less than 35% of individuals with a primary opioid or alcohol problem achieving successful outcomes one year following a recovery attempt (Sinha, 2011). Therefore, we focused investigation on these two time horizons: 1) < 1 year since AOD problem resolution and 2) 1–5 years since AOD problem resolution. Within these recovery periods, we investigated group differences between OPI and ALC on measures of treatment/recovery service utilization and indices of psychological well-being.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The National Recovery Survey (NRS; Kelly et al., 2017) is an online survey that targeted a US population of noninstitutionalized adults (age ≥ 18) who resolved a significant AOD problem, indicated via affirmative response to the screener question: “Did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?”.

As described in Kelly et al. (2017), the research team contracted with an internationally-recognized survey company, GfK (2013). Participants were recruited from GfK’s “KnowledgePanel”, which uses address-based sampling to randomly select individuals from 97% of all U.S. households per the Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File. GfK’s patented (U.S. Patent No. 7,269,570) probability proportional to size sampling strategy assures subsamples remain a reliable approximation of the U.S. population (for more information see: http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/knpanel/docs/knowledgepanel(R)-design-summary-description.pdf). Estimates derived via KnowledgePanel are comparable to national survey estimates obtained via non-internet-based recruitment and data collection methods (Bethell et al., 2004; Chang and Krosnick, 2009; Heeren et al., 2008; Novak et al., 2007; Yeager et al., 2011). For example, research demonstrate comparable estimates of current drinking obtained via a GfK KnowledgePanel sample and via NESARC (Heeren et al., 2008). Participants were screened between July and August 2016. Median time to survey completion was 24 minutes. From the initial sampling frame (N=39,809), 25,229 individuals successfully responded to the screener question (63.4% response rate). The final NRS study sample consisted of 2,002 individuals (i.e. unweighted N=2,002; final weighted N=1,980 after applying survey sampling weights) who answered ‘yes’ to the screener question. To obtain unbiased estimates and accurately represent the civilian population, data were weighted using the method of iterative proportional fitting (Battaglia et al., 2009). Base weights were computed and poststratification adjustments were made according to the Current Population Survey (United States Census Bureau, 2015) along eight dimensions: 1) gender, 2) age, 3) race/ Hispanic ethnicity, 4) education, 5) census geographical region, 6) household income, 7) home ownership status, and 8) metropolitan area. See Kelly et al. (2017) for a detailed description of weighting procedures. All study procedures were approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board.

For the current study, the final NRS weighted study sample was used to obtain prevalence estimates of opioid problem resolution and alcohol problem resolution among individuals with any AOD problem resolution. These estimates were then translated to national prevalence estimates (prevalence of ALC and OPI in the U.S. adult population), using the U.S. Census Bureau population estimate of American adults and the estimated prevalence of any AOD problem resolution in the U.S. (i.e. 9.1%; Kelly et al., 2017). To investigate OPI and ALC, within recovery durations of interest, the final NRS study sample was then subset into 4 groups based on primary substance (i.e. ALC, OPI) and problem resolution duration (i.e. less than 1 year since AOD problem resolution (<1 year), between 1 and 5 years since AOD problem resolution (1–5 years)). These four groups (unweighted N=357; weighted N=431) therefore included: 1) ALC reporting less than 1 year since problem resolution (weighted n=138; i.e. ALCE), 2) OPI reporting less than 1 year since problem resolution (weighted n=23; i.e. OPIE), 3) ALC reporting between 1 and 5 years since problem resolution (weighted n=227; i.e. ALCM), 4) OPI reporting between 1 and 5 years since problem resolution(weighted n=43; i.e. OPIM). Estimates for demographics, substance use histories, service utilization, and well-being were obtained among each of these four groups.

Measures

Substance Use and Problem Resolution.

Substance use histories were obtained with items from the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (Dennis, et al., 2002). Participants were shown a list of 15 substances (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, narcotics other than heroin, methadone, Suboxone/Subutex/buprenorphine, amphetamine/methamphetamine, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, hallucinogens, synthetic marijuana/synthetic drugs, inhalants, steroids, other substance), and were asked to indicate which substances they have used (not as prescribed, when applicable) 10 or more times in their lifetime. For each substance endorsed, the participant was then asked ‘was (substance) ever a problem for you?’. Of the substances endorsed as problematic, participants were then asked to indicate which one was their primary substance (i.e. drug of choice). Participants could only endorse a single substance as their primary problem substance and this measure was used to identify our primary substance groups of interest. Reported age at first use of their primary substance and age at cessation of primary substance use were used to derive measures of chronicity. Participants also reported how long it had been since they resolved their AOD problem, which was used to derive our resolution duration groups of interest.

Service Utilization.

Lifetime treatment/recovery service use was grouped into four dichotomous categories: 1) formal treatment (i.e. detoxification, outpatient, residential treatment), 2) mutual-help organizations (MHOs; i.e. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), other 12-step-based services, SMART Recovery, LifeRing Secular Recovery, Moderation Management, Celebrate Recovery, Women for Sobriety, Secular Organizations for Sobriety, “other”), 3) recovery support services (RSS; i.e. sober living, recovery high schools, college recovery programs/communities, recovery community centers, faith-based recovery services, state/local recovery community organizations), and 4) anti-relapse/craving pharmacotherapy (i.e. acamprosate, nalmefene, topiramate, disulfiram, baclofen, oral naltrexone, long-acting injectable naltrexone, methadone, levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, buprenorphine-naloxone, “other”). Additional questions addressed current anti-relapse/craving pharmacotherapy and past 90-days MHO attendance.

Psychological Well-Being.

Participants indicated whether they had ever received a diagnosis of alcohol or other drug use disorders (SUD), and 16 other psychiatric disorders (Non-SUD; Dennis et al., 2002). Psychological distress was measured with the Kessler-6, for which participants rated six symptoms on their frequency of occurrence (0=“none of the time” to 4=“all of the time”) over the past 30 days (Kessler et al., 2003). Single-item measures assessed current happiness (1=“completely unhappy” to 5=“completely happy”; Meyers and Smith, 1995) and self-esteem (i.e. “I have high self-esteem”, rated as 1=“not very true” to 5=“very true”; Robins et al., 2001). Current employment was evaluated dichotomously (yes/no).

Statistical Analyses

Weighted frequencies were used to obtain OPI and ALC prevalence estimates from the final NRS weighted sample (weighted N=1980), across resolution periods. Subsequent analyses targeted: 1) OPI and ALC in early recovery (i.e. OPIE and ALCE; <1 year since problem resolution) and 2) OPI and ALC in mid recovery (i.e. OPIM and ALCM; 1–5 years since problem resolution). Prevalence estimates were obtained for OPI and ALC within these two resolution periods, again using the final NRS weighted sample. Using survey-weighted estimation methods, including cross tabulations (via SAS procedure ‘proc surveyfreq’) and analysis of variance (ANOVA via SAS procedure ‘proc surveyreg’ for weighted sample survey data) , we compared demographics and substance use histories, service utilization, and indices of well-being as a function of primary problem substance, within each resolution period (i.e. OPIE vs. ALCE and OPIM vs. ALCM). We calculated descriptive measures detailing the use of specific service sub-types and conducted significance tests whenever feasible. Given group differences in age, this variable was introduced as a covariate in post-hoc analyses to assess its influence whenever possible; outcomes were unchanged when controlling for age. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4. Significance was defined as p≤0.05.

Results

Prevalence Estimates

Of those who resolved any AOD problem, 5.30% (SE=0.77%; n=105) reported opioids as their primary substance. This number translates to 1.18 million U.S. adults who have resolved a primary opioid problem. Regarding specific time-periods of resolution, 1.16% (SE=0.41%; n=23) reported less than one year since opioid problem resolution and 2.19% (SE=0.56%; n=43) reported one to five years since opioid problem resolution. These numbers translate to approximately 259,260 and 489,465 U.S. adults, respectively. 51.15% (SE=1.61; n=1013) reported resolving a primary alcohol problem, translating to 11.43 million U.S. adults who have resolved a primary alcohol problem. 6.99% (SE=0.86%; n=138) had less than one year since alcohol problem resolution (~1.56 million U.S. adults) and 11.46% (SE=1.06%; n=227) had one to five years since alcohol problem resolution (~2.56 million U.S. adults).

The early-recovery cohort consisted of 161 individuals with alcohol (85.75%, SE=4.67%, n=138; i.e. ALCE) or opioid (14.25%, SE=4.67%; n=23; i.e. OPIE) problem resolution. The mid-recovery cohort consisted of 270 participants with alcohol (83.95%, SE=3.75%, n=227; i.e. ALCM) or opioid (16.05%, SE=3.75%, n=43; i.e. OPIM) problem resolution. OPI and ALC comparisons, conducted within early- and mid- recovery cohorts, are reported below.

Demographics and Substance Use Histories

Demographic and substance use variables are presented in Table 1. OPIE were younger than ALCE (F1,356=16.20, p<0.0001) and more likely to identify as white (χ2=7.54, p=0.006). Groups did not differ with regard to male/female sex. Although ALCM and OPIM did not significantly differ with regard to age, sex, or race, the data showed trends similar to those observed in the early-recovery cohort (age: F1,356=2.70, p=0.10; race: χ2=2.56, p=0.10).

Table 1.

Demographics, Substance Use Histories, and Well-Being (Within Drug Group & Recovery Cohort)

| 0–1 Years | 1–5 Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPI | ALC | p | OPI | ALC | p | |

| Age, M(SE) | 27.53 (2.46) | 39.59 (1.70) | ** | 35.38 (2.68) | 40.27 (1.28) | NS |

| Sex, % male (SE) | 60.05 (15.91) | 59.21 (6.13) | NS | 46.63 (13.27) | 57.75 (4.75) | NS |

| Race, % white (SE) | 94.29 (5.76) | 61.37 (6.72) | ** | 76.16 (11.05) | 54.48 (5.07) | NS |

| Number of Problem Substances (lifetime), M(SE) | 2.45 (0.49) | 1.38 (0.09) | * | 3.20 (0.30) | 1.23 (0.05) | ** |

| Age of Onset (first use of primary substance), M(SE) | 18.27 (1.27) | 15.10 (0.46) | * | 22.39 (2.15) | 15.32 (0.54) | ** |

| Duration of Primary Substance Use Prior to Cessation (years), M(SE) | 8.36 (2.22) | 21.89 (2.34) | ** | 9.08 (1.37) | 23.04 (1.44) | ** |

| Time Since Problem Resolution (years), M(SE) | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.50 (0.05) | NS | 2.67 (0.28) | 3.18 (0.12) | NS |

| Opioid of Choice, % narcotics other than heroin (SE) | 77.47 (12.64) | — | — | 57.66 (13.70) | — | — |

| Substance Use Disorder Diagnosis (lifetime), % yes (SE) | 31.54 (19.23) | 25.40 (5.64) | NS | 34.59 (15.58) | 29.15 (4.58) | NS |

| Non-SUD psychiatric Diagnosis (lifetime), % yes (SE) | 51.83 (19.69) | 43.40 (6.40) | NS | 43.89 (14.33) | 37.96 (4.83) | NS |

| Psychological Distress (past 30 days), M(SE) | 9.31 (1.96) | 7.62 (0.73) | NS | 6.56 (1.00) | 5.73 (0.53) | NS |

| Happiness (current), M(SE) | 3.08 (0.32) | 3.25 (0.11) | NS | 3.54 (0.21) | 3.60 (0.10) | NS |

| Employed (current), % yes (SE) | 77.58 (10.97) | 62.69 (6.16) | NS | 59.32 (12.30) | 61.99 (4.78) | NS |

OPI=individuals who resolved a primary opioid problem; ALC=individuals who resolved a primary alcohol problem; Non-SUD psychiatric diagnosis includes agoraphobia, anorexia, bulimia, bipolar disorder (I or II), delusional disorder, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia; Psychological Distress: scores range from 0 (no distress) to 24 (high distress); Happiness: scores range from 1=“completely unhappy” to 5=“completely happy”; Significant difference between OPI and ALC, within recovery cohort:

P≤0.05,

P≤0.01;

NS=not significant; ‘—’=significance testing not applicable; see text for more detail.

Relative to ALC, OPIE and OPIM reported problematic use of more substances (early-recovery: F1,356=4.61, p=0.03; mid-recovery: F1,356=42.24, p<0.0001), older age at first use of their primary substance (early-recovery: F1,356=2.34, p=0.02; mid-recovery: F1,356=10.14, p=0.002), and shorter duration of primary substance use prior to cessation (early-recovery: F1,224=17.48, p<0.0001; mid-recovery: F1,224=48.99, p<0.0001). The majority of OPIE and OPIM endorsed non-heroin narcotics as their primary substance.

Service Utilization

Lifetime.

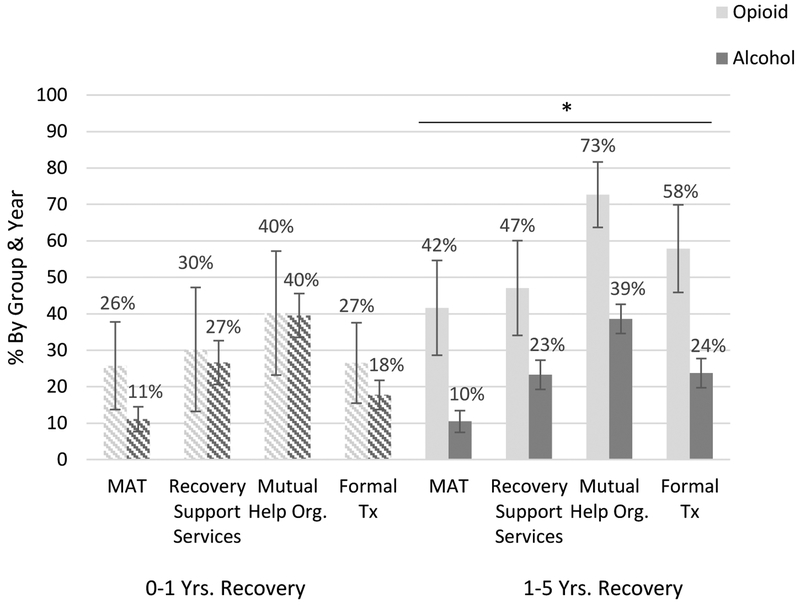

Lifetime utilization of formal treatment, MHOs, RSS, and pharmacotherapy did not differ between OPIE and ALCE. Conversely, OPIM exhibited significantly greater utilization of all services than ALCM (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lifetime Use of Treatment & Recovery Services.

Among individuals with 1–5 years of recovery, OPI were more likely to endorse lifetime utilization of formal treatment services (χ2=8.60, p=0.0034), mutual-help services (χ2=8.99, p=0.0027), recovery support services (χ2=3.84, p=0.05), and pharmacotherapy (i.e. MAT; χ2=10.09, p=0.0015), relative to ALC (horizontal bar and asterisk reflect P≤0.05 across all services). Lifetime use of these services did not significantly differ between OPI and ALC in the first year of recovery (all p’s > 0.05). Error bars depict standard error.

Current.

Current use of pharmacotherapy (Table 2) was more prevalent among OPIM than ALCM (χ2=3.72, p=0.05). OPIE and ALCE comparisons did not reach statistical significance (χ2=2.43, p=0.12). Current use of any MHO did not differ between OPI and ALC in either recovery cohort. 12-step MHOs were much more common than non-12-step MHOs across all groups. Further examination of 12-step service use revealed more prevalent NA attendance in OPIE than ALCE (χ2=19.08, p<0.0001) and in OPIM compared to ALCM (χ2=10.37, p=0.001). Current AA attendance did not differ between OPI and ALC in either recovery cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Current Service Utilization (Within Drug Group & Recovery Cohort)

| 0–1 Years | 1–5 Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | p | % (SE) | p | |||

| OPI | ALC | OPI | ALC | |||

| Any Mutual-Help Service (current) | 26.76 (18.04) | 16.06 (4.90) | NS | 12.76 (9.65) | 16.05 (3.50) | NS |

| Any Non-12-Step Service | 2.38 (2.48) | 2.88 (1.33) | NS | 1.08 (1.11) | 2.60 (1.44) | NS |

| Any 12-Step Service | 26.76 (18.04) | 14.60 (4.86) | NS | 12.76 (9.65) | 13.73 (3.28) | NS |

| Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) | 22.11 (18.34) | 14.60 (4.86) | NS | 11.43 (9.62) | 11.22 (2.61) | NS |

| Narcotics Anonymous (NA) | 26.76 (18.04) | 1.66 (0.97) | ** | 12.76 (9.65) | 1.17 (0.61) | ** |

| Other 12-Step Services (MA, CA, or CMA) | 0 (0) | 0.54 (0.54) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 2.53 (2.22) | NS |

| Any Pharmacotherapy (current) | 14.45 (8.40) | 4.42 (2.22) | NS | 20.12 (10.48) | 5.07 (2.02) | * |

| Methadone | 2.09 (2.18) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 1.00 (0.99) | — |

| Levomethadyl acetate (Orlaam) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 2.24 (2.20) | — |

| Buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) | 12.36 (7.92) | 1.74 (1.73) | NS | 8.77 (5.44) | 0 (0) | — |

| Buprenorphine (Subutex) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0.32 (0.32) | — |

| Oral Naltrexone (Revia) | 0 (0) | 0.87 (0.62) | — | 0 (0) | 0.18 (0.13) | — |

| Long-acting injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 1.33 (1.32) | — |

| Acamprosate (Campral) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Nalmefene (Selincro) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 2.24 (2.20) | NS |

| Topiramate (Topamax) | 0 (0) | 0.96 (0.96) | — | 1.00 (1.03) | 0 (0) | — |

| Disulfiram (Antabuse) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Baclofen (Lioresal) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Other Pharmacotherapy | 0 (0) | 0.85 (0.85) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

OPI=individuals who resolved a primary opioid problem; ALC=individuals who resolved a primary alcohol problem; MA=Marijuana Anonymous; CA=Cocaine Anonymous; CMA=Crystal Methamphetamine Anonymous; Values depict the distribution of individuals reporting mutual help service use in the past 90 days and current ongoing pharmacotherapy; Significant difference between OPI and ALC, within recovery cohort:

P≤0.05,

P≤0.01;

NS=not significant; ‘—’=significance testing not applicable; see text for more detail.

Psychological Well-Being

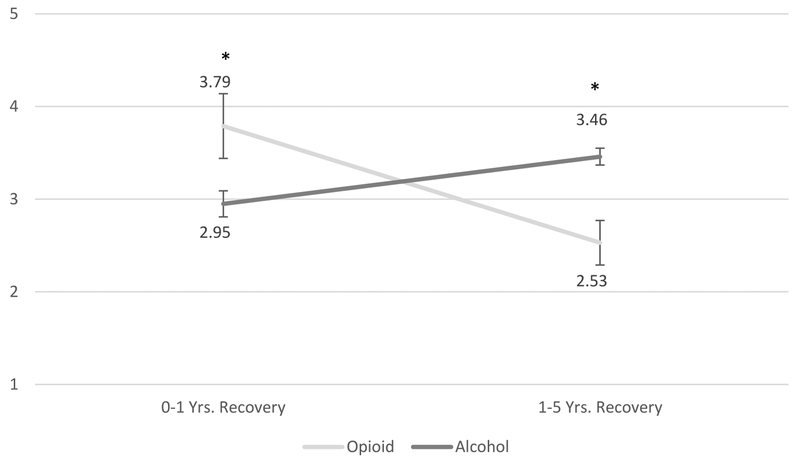

OPIE (M=3.79, SE=0.36) reported higher self-esteem than ALCE (M=2.95, SE=0.15), whereas the opposite pattern was observed among the mid-recovery cohort (MOPI=2.53, SE=0.25; MALC=3.46, SE=0.10; Figure 2). Lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, past 30-days psychological distress, current happiness, and employment did not differ significantly between OPI and ALC in either recovery cohort (Table 1).

Figure 2. Current Self-Esteem.

Relative to ALC, current level of self-esteem was higher in OPI with 0–1 years of recovery (F1, 354=4.79, p=0.03), but lower in OPI with 1–5 years of recovery (F1, 354=11.91, p<0.001). Values shown are mean scores, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of self-esteem. Error bars depict standard error. *P<0.05.

Detailed Descriptives: Service Sub-Types

Lifetime.

Lifetime use of specific service sub-types is depicted in Table 3. Outpatient treatment was the most common formal treatment used among OPIE. Outpatient and inpatient treatment were equally common among OPIM and among both ALC cohorts. 12-step-based organizations (AA/NA) were the most common MHOs used among all groups. Regarding RSS, OPIE primarily used recovery community centers, whereas ALCE exhibited a relatively more distributed service use pattern. OPIM and ALCM endorsed an even wider variety of RSS; ~1/4 of OPIM used recovery community centers and state/local recovery community organizations, and ~1/7 used sober living and faith-based services. Less than 10% of ALCM used any individual RSS, but reports spanned all RSS sub-types. Buprenorphine was the most common pharmacotherapy ever used among OPIE and OPIM. Lifetime use of individual pharmacotherapies among ALC was low across the board (< 4% for any given medication).

Table 3.

Lifetime Service Utilization (Within Drug Group & Recovery Cohort)

| 0–1 Years | 1–5 Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | p | % (SE) | p | |||

| OPI | ALC | OPI | ALC | |||

| Any Formal Treatment | 26.53 (11.84) | 17.78 (4.45) | NS | 57.90 (12.39) | 23.72 (4.08) | ** |

| Inpatient / Residential | 11.72 (6.57) | 11.44 (3.95) | NS | 37.83 (12.96) | 13.39 (3.22) | * |

| Outpatient | 25.69 (11.66) | 11.90 (3.24) | NS | 35.59 (13.17) | 12.68 (2.65) | * |

| Detoxification | 13.40 (7.73) | 10.53 (3.82) | NS | 18.54 (11.16) | 8.52 (2.84) | NS |

| Any Mutual-Help Service | 40.19 (17.82) | 39.54 (6.18) | NS | 72.70 (9.98) | 38.62 (4.61) | ** |

| Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) | 37.93 (17.85) | 36.91 (6.15) | NS | 36.99 (12.55) | 31.60 (4.17) | NS |

| Narcotics Anonymous (NA) | 40.19 (17.82) | 6.38 (2.47) | ** | 57.79 (12.48) | 8.96 (2.41) | ** |

| Other 12-Step Services (MA, CA, or CMA) | 0 (0) | 2.64 (1.84) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 3.32 (2.27) | NS |

| SMART Recovery | 2.38 (2.48) | 0.55 (0.55) | NS | 0 (0) | 3.39 (1.66) | — |

| LifeRing Secular Recovery | 0.84 (0.88) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0.14 (0.14) | — |

| Moderation Management | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Celebrate Recovery | 0 (0) | 1.53 (1.03) | — | 1.00 (1.03) | 2.30 (1.11) | NS |

| Women for Sobriety | 0 (0) | 0.60 (0.60) | — | 1.08 (1.11) | 4.16 (2.31) | NS |

| Secular Organizations for Sobriety | 0 (0) | 1.45 (1.04) | — | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Other Mutual-Help Service | 0 (0) | 2.92 (1.41) | — | 1.08 (1.11) | 2.69 (1.03) | NS |

| Any Recovery Service | 30.20 (17.87) | 26.66 (5.94) | NS | 47.08 (13.18) | 23.26 (4.29) | * |

| Sober living environment | 0 (0) | 12.16 (4.94) | — | 16.71 (10.93) | 8.67 (3.12) | NS |

| Recovery High Schools | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 5.44 (2.75) | — |

| College Recovery Programs/Communities | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 4.00 (3.98) | 5.18 (2.58) | NS |

| Recovery Community Centers | 27.23 (17.99) | 9.70 (3.98) | NS | 23.15 (12.98) | 4.51 (1.73) | ** |

| Faith-Based Recovery Services | 3.62 (3.21) | 10.63 (4.03) | NS | 12.57 (9.68) | 8.60 (2.82) | NS |

| State or Local Recovery Community Organization | 0 (0) | 4.98 (2.32) | — | 24.44 (13.47) | 1.83 (1.00) | ** |

| Any Pharmacotherapy | 25.75 (13.00) | 11.13 (3.49) | NS | 41.64 (12.95) | 10.49 (3.10) | ** |

| Methadone | 2.09 (2.18) | 0 (0) | — | 3.61 (3.61) | 1.00 (0.99) | NS |

| Levomethadyl acetate (Orlaam) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 2.89 (2.29) | — |

| Buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) | 15.29 (8.56) | 1.74 (1.73) | * | 26.67 (11.52) | 1.65 (1.36) | ** |

| Buprenorphine (Subutex) | 14.45 (8.40) | 1.74 (1.73) | * | 3.09 (3.10) | 0.75 (0.54) | NS |

| Oral Naltrexone (Revia) | 12.85 (10.35) | 3.26 (1.50) | NS | 11.36 (9.62) | 1.15 (0.67) | ** |

| Long-acting injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol) | 10.47 (10.05) | 0 (0) | — | 0 (0) | 1.33 (1.32) | — |

| Acamprosate (Campral) | 2.38 (2.48) | 0.55 (0.55) | NS | 0 (0) | 0.97 (0.67) | — |

| Nalmefene (Selincro) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 2.89 (2.28) | NS |

| Topiramate (Topamax) | 0 (0) | 0.96 (0.96) | — | 1.00 (1.03) | 0 (0) | — |

| Disulfiram (Antabuse) | 0 (0) | 3.73 (1.62) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 2.53 (1.05) | NS |

| Baclofen (Lioresal) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | 10.35 (9.62) | 0 (0) | — |

| Other Pharmacotherapy | 2.38 (2.48) | 3.11 (2.37) | NS | 0 (0) | 1.16 (0.99) | — |

OPI=individuals who resolved a primary opioid problem; ALC=individuals who resolved a primary alcohol problem; Values depict the distribution of specific treatment and recovery services used across the lifetime. Percentages were calculated for each drug-group, within recovery-duration cohort; Significant difference between OPI and ALC, within recovery cohort:

P≤0.05,

P≤0.01;

NS=not significant; ‘—’=significance testing not applicable; see text for more detail.

Current.

Current pharmacotherapy among ALC was uncommon (< 3% for any given medication). ~1/8 of OPIE and ~1/11 of OPIM reported ongoing buprenorphine treatment. The opioid antagonist, nalmafene, was also endorsed by ~10% of OPIM (Table 2).

Discussion

This study provides the first national estimate of opioid problem recovery prevalence, and characterizes service utilization patterns and psychological well-being in a national probability-based sample of U.S. adults with opioid problem resolution. By comparing OPI to ALC within specific and critical recovery windows, this investigation lends insight into the ways in which individuals might achieve longer durations of recovery from opioid use problems. Given the emphasis of prior research on treatment seeking populations, investigating problem resolution outside the context of addiction treatment settings also provides a unique perspective on recovery pathways.

An estimated 9.1%, or 22.35 million, American adults report having resolved a significant AOD problem (Kelly et al., 2017). Accordingly, the current study’s prevalence estimate of 5.30% translates to 1.18 million U.S. adults who have resolved a primary opioid problem (i.e. 0.48% of the US adult population). Regarding specific windows of recovery, our prevalence estimate of 1.16% in the first year of problem resolution and 2.19% with 1 to 5 years since problem resolution translates to approximately 259,260 and 489,465 U.S. adults, respectively. Given that an estimated 10.6 million American adults have misused opioids in the past year and ~2 million adults meet DSM criteria for a past-year opioid use disorder (SAMHSA, 2018), the relatively small estimates observed in this study speak to the potential gap between problem use and problem resolution prevalence.

Compared to ALC, OPI were younger and more likely to identify as white. However, this difference only reached statistical significance among the early-recovery cohort, suggesting a slight narrowing of this demographic differentiation in mid-recovery. Several OPI-ALC differences emerged for substance use histories within both recovery cohorts. OPI reported problematic use of more substances, reflecting potentially more severe substance use careers than ALC. Consistent with prior reports (Shmulewitz et al., 2015; Mendelson et al., 2008), OPI were older upon first use of their primary substance. Furthermore, OPI had less time between first use and cessation of primary substance use than ALC, suggesting opioid-related telescoping (i.e. faster progression through substance use/recovery milestones). Relative to alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine, opioids are shown to be associated with the most rapid transition from initial use to regular use, problem use, and dependence (Ridenour et al., 2006). Our outcomes suggest this telescoping effect extends to problem resolution milestones, perhaps due to more rapid progression to problematic opioid use and related consequences.

Service Utilization

Regarding past 90-day MHO use, both early- and mid-recovery OPI exhibited higher rates of NA attendance and similar rates of AA attendance, relative to ALC. Outcomes suggest essentially all 12-step-attending OPI utilized both NA and AA, potentially reflecting NA’s reduced availability. Alternatively, stigma surrounding OUD pharmacotherapy in the context of NA meetings might encourage OPI to attend AA meetings, as some report AA to be more accepting of medication treatment (White, 2011). Some OUD pharmacotherapy patients might prefer AA due to its perceived ability to provide more structure and a stronger spiritual framework than NA (White et al., 2013). Nonetheless, NA and AA are shown to equally benefit individuals recovering from SUD (Kelly et al., 2014). Therefore, OPI’s use of both services is likely not cause for concern. It may even enrich the recovery of individuals with opioid problems and have a conferred additive effect independent of pharmacotherapy (Weiss et al., 2019).

More importantly, OPI and ALC differed on several other indices of service utilization, which were only observed in the mid-recovery cohort. Specifically, lifetime use of formal treatment, pharmacotherapy, RSS, and MHOs were all more prevalent among OPI than ALC. Mid-recovery OPI were 4X as likely to have used pharmacotherapy, 2.5X more likely to have used formal treatment, and about 2X more likely to have used RSS and MHOs, relative to ALC. In early recovery, OPI rates of service utilization were substantially lower and did not significantly differ from ALC. Mid-recovery OPI also had higher rates of ongoing pharmacotherapy, which might reflect the differential duration of medication treatment necessary to maintain longer-term recovery from opioid versus alcohol problems, or the relative efficacy of medications for treating opioid versus alcohol problems.

OPI-ALC differences suggest specificity according to recovery duration and speak to potential avenues for facilitating longer-term recovery in OPI. OUD is a persisting and relapsing disorder for which recovery is particularly difficult (Smyth et al., 2010). OPI who reached recovery beyond one year reported substantially greater service use. Furthermore, detailed descriptive measures concerning the use of specific sub-types of formal treatment, pharmacotherapy, MHOs, and RSS, suggest this cohort has used multiple services within these categories. Together, these outcomes suggest that individuals with opioid problems might require additional treatment attempts and/or more clinical resources to achieve longer recovery durations. Indeed, prior work shows that past-year remission, without service utilization, is less probable for drug use disorders (McCabe et al., 2016) and somewhat more probable for alcohol use disorders (Dawson et al., 2006, 2007; Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). While opioid cessation at relatively early stages of one’s substance use career is possible without intervention, stable cessation is often not achieved until a few years following an initial recovery attempt. Though multiple treatment episodes are common with opioid problems, longer cumulative treatment durations are associated with better outcomes (Hser et al., 2015). Therefore, attainment of problem resolution with less probable use of clinical/recovery resources, at least in the early stages of recovery, may constitute an important marker of vulnerability. With only about one-quarter reporting use of formal treatment and pharmacotherapy, and 30–40% using RSS and MHOs, early-recovery OPI may be taking a ‘DIY’ approach to problem resolution, placing them in a more vulnerable position. Continued care and support appear more important for OPI than what is typically advised and provided for ALC. Encouraging additional, prolonged clinical care and recovery support may be warranted to help OPI patients maintain problem resolution beyond the first year.

Psychological Well-Being

Regardless of resolution duration, OPI and ALC were similar with respect to psychiatric diagnoses, psychological distress, happiness and employment. Interestingly, self-esteem was higher in OPI than ALC in early recovery, whereas the opposite effect was observed among the mid-recovery cohort.

Service use has the potential to play a role in these self-esteem outcomes. The current political climate and societal beliefs surrounding opioids might perpetuate negative attitudes toward one’s ability to achieve successful treatment and recovery. Upon initially resolving an opioid use problem, individuals may feel a particular sense of self-worth, knowing they achieved the ‘unachievable’. However, lapses in recovery may result in the need for more clinical and recovery services, such as a first attempt at formal treatment or multiple treatment episodes. Individuals may realize that they need more intensive care, medication, and recovery support to avoid such lapses and maintain recovery. Evidence suggests that ‘hitting bottom’, (i.e. greater drug-related consequences and compromised well-being) predicts attainment of sustained longer-term remission (Laudet et al., 2002; Matzger et al., 2005). This, coupled with fluctuating periods of resolution and return to problem use, may have the potential to bring about feelings of failure or shame, and subsequently deflate self-esteem. Indeed, OPI are a more vulnerable recovery cohort in general; they are less likely to disclose their recovery status (Earnshaw et al., 2019) and report less recovery capital (i.e. availability, accessibility, and attainment of recovery resources, such as social support and financial resources) than ALC (Kelly et al., 2018). Although recovery capital is substantially lower in OPI upon resolving a problem, it typically reaches levels equivalent to ALC by recovery year three (Kelly et al, 2018). Given an average of about three years since problem resolution among our mid-recovery sample, recovery capital may not constitute a specific problem for this cohort. However, our findings suggest that another measure of well-being (i.e. self-esteem) could be compromised and warrants additional attention. Self-esteem outcomes are not likely to be due to variability in descriptive characteristics or other indices of well-being studied here, given that observed differences between OPI and ALC were largely comparable between the early- and mid-recovery cohorts. Additional research will help clarify whether recurrent recovery attempts and service utilization play a direct role in self-esteem throughout the course of OPI recovery. Nonetheless, negative affect often plays a role in relapse (Larimer et al., 1999) and addressing deficiencies in self-esteem could therefore promote well-being and aid recovery maintenance. Continued MHO participation may help address this issue by providing opportunities to celebrate recovery and promote positive self-perceptions.

Limitations

The study’s findings should be considered in light of important limitations. (1) Individuals self-identified AOD problem resolution, which includes but does not necessarily indicate a diagnostic disorder or remission. Still, studying this nationally-representative group of individuals is of particular public health significance, because it captures a broader population of individuals suffering from substance use problems that include but is not limited to meeting diagnostic thresholds (Kelly et al., 2017). In 2017, 11.1 million individuals reported past-year pain reliever misuse, but only 1.7 million met DSM criteria for a prescription opioid use disorder (Office of the Surgeon General, 2018). Accordingly, understanding this population with problem use and resolution can ultimately provide important public health information. (2) This is a cross-sectional study and caution is warranted when making inferences about prospective changes and causal connections between problem resolution durations. These data provide a foundation for future longitudinal research, which is necessary to inform dynamic changes across recovery trajectories. (3) Low rates of sober living service utilization were observed among the early-recovery cohort. Although lifetime service use was assessed and GfK offered participant resources for survey completion (web-enabled computer and free Internet service), sober living environments may limit opportunity for online survey participation, creating the potential for underrepresentation. GfK’s address-based sampling excludes institutionalized, incarcerated, and homeless individuals. Excluding these individuals has the potential to underestimate opioid and/or alcohol problem resolution prevalence, given the psychosocial disruptions associated with AOD, particularly opioid, problems. Furthermore, unexpectedly high estimates were observed for certain pharmacotherapy response items (e.g., nalmafene). Although participants can typically recall the purpose of their current medications, our clinical and recruiting experience has revealed that about one-half cannot recall their medications’ names. Therefore, pharmacotherapy outcomes should be interpreted with self-report limitations in mind. (4) This sample represents individuals with any self-reported problem use history of any type of opioid. We are unable to test moderator effects by type of opioid (e.g., prescription opioids vs heroin) given the size of the sample. This is an area for future research to help determine whether findings herein are more representative of those with prescription opioid vs heroin misuse. (5) Confidence in the current study’s estimates is moderate, given that relatively small OPI sample sizes and enhanced variability in these groups has the potential to increasing type II error. However, it is important to consider that although opioid use disorder is a major public health problem, rates of alcohol use disorder are far greater. Funneling this population further, even fewer would be expected to resolve their substance use problem and our sample sizes reflect that. Despite its limitations, this study provides a first glimpse at a nationally representative sample of individuals who have resolved an opioid problem, offering important national prevalence and other benchmarks for future research and addressing a drastically understudied population, at a time when their characterization is vital.

Conclusions

Given the scope of opioid misuse and the multitude of consequences resulting from it in recent years, preliminary data regarding the ways in which individuals resolve opioid use problems can ultimately help inform approaches to effectively address it. The current study provides the first national estimates of opioid problem resolution and compares treatment/recovery service utilization and psychological well-being in individuals with opioid (OPI) VS alcohol (ALC) problem resolution, across critical recovery time horizons. Our findings suggest that ~1.2 million U.S. adults have resolved a primary opioid problem (~259,000 with <1 year [early-recovery] and ~489,000 with 1–5 years [mid-recovery] since problem resolution). Whereas the use of treatment/recovery services was more prevalent among OPI than ALC in mid-recovery, service use histories did not differ in the early-recovery cohort. Furthermore, OPI exhibited higher self-esteem in early-recovery and lower self-esteem in mid-recovery, relative to ALC within equivalent recovery periods. Outcomes suggest service use, on average, may be more important for OPI than what is typically advised for ALC. Prolonged clinical care and additional recovery support may be needed to help OPI patients maintain longer-term problem resolution. Self-esteem outcomes also suggest OPI-specific vulnerabilities that warrant attention beyond recovery year one to promote well-being and resolution maintenance. With opioid misuse constituting a major public health problem, longitudinal research is needed to confirm the outcomes of this cross-sectional preliminary investigation. Further investigation will help to characterize the influence of other potentially relevant factors (e.g., number of recovery episodes), and identify which continued care approaches best predict prolonged opioid problem resolution and enhanced well-being during recovery.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Recovery Research Institute at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. The authors declare no financial or other conflict of interests that could affect the integrity or veracity of this work.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

This research was supported by the Recovery Research Institute at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Dr. Hoffman was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32 DA047741. Dr. Vilsaint and Dr. Kelly were supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers F32AA025823 and K24AA022136, respectively. The authors declare no financial or other conflict of interests that could affect the integrity or veracity of this work.

References

- Adamson SJ, Sellman JD, Frampton CM. Patient predictors of alcohol treatment outcome: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009; 36(1):75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia MP, Hoaglin DC, Frankel MR. Practical considerations in raking survey data. Surv Pract 2009; 2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C, Fiorillo J, Lansky D, Hendryx M, Knickman J. Online consumer surveys as a methodology for assessing the quality of the United States health care system. J Med Internet Res 2004; 2(e2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Krosnick JA. National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opin Q 2009; 73(4):641–678. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A 3-year follow-up. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007; 31:2036–2045. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson, FS, Chou, PS. Estimating the effect of help-seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction 2006; 101:824–834. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White MK, Unsicker JI, Hodgkins D. Global appraisal of individual needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, Civita MD, Paraherakis A, Gill K. The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction 2002; 97(3):347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V, Bergman BG, Kelly JF. Whether, when, and to whom?: An investigation of comfort with disclosing alcohol and other drug histories in a nationally representative sample of recovering persons. J Subst Abuse Treat 2019; 101:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GfK. KnowledgePanel design summary. Available at: http://images.politico.com/global/2014/09/12/knowledgepanelr-design-summary-description.pdf; 2013.

- Gossop M, Stewart D, Browne N, Marsden J. Factors associated with abstinence, lapse or relapse to heroin use after residential treatment: Protective effect of coping responses. Addiction 2002; 97(10):1259–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren T, Edwards EM, Dennis JM, Rodkin S, Hingson RW, Rosenbloom DL. A comparison of results from an alcohol survey of a prerecruited Internet panel and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2008; 32(2):222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Grella C, Ling W, Anglin D Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2015; 23(2):76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JK, Bergman B, Hoeppner BB, Vilsaint C, White WL. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: Implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017; 181:162–169. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG. Do drug-dependent patients attending alcoholics anonymous rather than narcotics anonymous do as well? A prospective, lagged, matching analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 2014; 49(6):645–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG. Beyond abstinence: Changes in indices of quality of life with time in recovery in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2018; 42(4):770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention an overview of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health 1999; 23(2):151–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A, Savage R, Mahmood D. Pathways to long-term recovery: A preliminary investigation. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002; 34:305–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, Van Horn SL. Trends in substance use disorders among adults aged 18 or older: The CBHSQ report. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Hasin DS, Cabos JP, et al. Probability and predictors of remission from life-time nicotine, alcohol, cannabis or cocaine dependence: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Addiction 2011; 106:657–669. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2014; (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzger H, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C Reasons for drinking less and their relationship to sustained remission from problem drinking. Addiction 2005; 100(11):1637–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. Stressful events and other predictors of remission from drug dependence in the United States: Longitudinal results from a national survey. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016; 71:41–47. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson J, Flower K, Pletcher MJ, Galloway GP. Addiction to prescription opioids: Characteristics of the emerging epidemic and treatment with buprenorphine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2008; 16(5):435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Smith J. Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The community reinforcement approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, Linas BP, Walley AY. Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018; 85:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak SP, Kroutil LA, Williams RL, Van Brunt DL. The nonmedical use of prescription ADHD medications: results from a national Internet panel. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2007; 2(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in america: the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour TA, Lanza ST, Donny EC, Clark DB. Different lengths of times for progressions in adolescent substance involvement. Addict Behav, 2006; 31(6):962–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH. Measuring global self esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2001; 27:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Scott TM, Mindt MR, Cunningham CO, et al. Neuropsychological function is improved among opioid dependent adults who adhere to opiate agonist treatment with buprenorphine-naloxone: a preliminary study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2017; 12(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Greene ER, Hasin D. Commonalities and differences across substance use disorders: Phenomenological and epidemiological aspects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015; 39(10):1878–1900. doi: 10.1111/acer.12838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R New findings on biological factors predicting addiction relapse vulnerability. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011; 13(5):398–405. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth BP, Barry J, Keenan E, Ducray K. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J 2010; 103(6):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuse Substance and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 national survey on drug use and health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18–5068, NSDUH Series H-53). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Current Population Survey (CPS). Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/about.html; 2015.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General,

- Facing addiction in America: the surgeon general’s spotlight on opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Marcovitz DE, Hilton BT, Fitzmaurice GM, McHugh RK, Carroll KM. Correlates of opioid abstinence in a 42-month posttreatment naturalistic follow-up study of prescription opioid dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 2019; 80(2). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W Recovery management and recovery-oriented systems of care (Vol. 6). Chicago: Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Northeast Addiction Technology Transfer Center and Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Mental Retardation Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- White WL. Narcotics Anonymous and the pharmacotherapeutic treatment of opioid addiction in the United States. Chicago: Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services & Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- White WL. Recovery/remission from substance use disorders: An analysis of reported outcomes in 415 scientific reports, 1868–2011. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Campbell MD, Shea C, Hoffman HA, Crissman B, DuPont RL. Coparticipation in 12-step mutual aid groups and methadone maintenance treatment: A survey of 322 patients. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery 2013; 8(4):294–308. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Krosnick JA, Chang L, et al. Comparing the accuracy of RDD telephone surveys and internet surveys conducted with probability and non-probability samples. Public Opin Q 2011; 75(4):709–747. [Google Scholar]