Abstract

Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) are found in 6% of AML patients. Mutant IDH produces R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R2HG), which induces histone- and DNA-hypermethylation through inhibition of epigenetic regulators, thus linking metabolism to tumorigenesis. Here we report the biochemical characterization, in vivo antileukemic effects, structural binding and molecular mechanism of the inhibitor HMS-101, which inhibits the enzymatic activity of mutant IDH1 (IDH1mut). Treatment of IDH1mut primary AML cells reduced 2-hydroxyglutarate levels (2HG) and induced myeloid differentiation in vitro. Co-crystallization of HMS-101 and mutant IDH1 revealed that HMS-101 binds to the active site of IDH1mut in close proximity to the regulatory segment of the enzyme in contrast to other IDH1 inhibitors. HMS-101 also suppressed 2HG production, induced cellular differentiation and prolonged survival in a syngeneic mutant IDH1 mouse model and a patient-derived human AML xenograft model in vivo. Cells treated with HMS-101 showed a marked upregulation of the differentiation-associated transcription factors CEBPA and PU.1, and a decrease in cell cycle regulator cyclin A2. In addition, the compound attenuated histone hypermethylation. Together, HMS-101 is a unique inhibitor that binds to the active site of IDH1mut directly and is active in IDH1mut preclinical models.

Introduction

Mutations in the active site arginine residue (R132) of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) have been found in about 6-10% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients,1, 2 which confer a neomorphic function to the mutant enzyme and result in elevated levels of R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG).3, 4 IDH1 mutations lead to a block in cellular differentiation and promote tumorigenesis partly due to global DNA and histone hypermethylation by disruption of α-ketoglutarate dependent enzymes through R-2HG.5–7 Thus, the inhibition of oncogenic mutant IDH1 represents an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. The crystal structures reported from X-ray crystallographic studies are currently being used as protein models of choice to screen inhibitors which specifically target mutant IDH1, while sparing wildtype IDH1.3 Human cytosolic IDH1 consists of asymmetric subunits forming a dimer. The crystal structure of wildtype IDH1 consists of a large domain, a small domain and a clasp domain.8 A deep cleft is formed by the large domain, the small domain and a second small domain from a different subunit, which together form the active site of the enzyme.8 The hydrophilic active site has pockets for isocitrate, a metal ion, and NADP binding sites.8 An amino acid change at arginine 132 in the active site to histidine or cysteine induces a conformational change leading to increased affinity to α-ketoglutarate, which is then catalyzed to R-2HG.9 Thus, altered substrate binding affinity confers a neomorphic function to the mutant IDH1 enzyme.

Several IDH1 inhibitors have been designed that can target the conformational change induced by a single mutated amino acid, and some of the IDH1 inhibitors like AG-120, IDH-305, FT-2102 and BAY1436032 have entered clinical trials or even have been approved (AG120/ivosidenib).10–16 Crystal structures of several IDH1 inhibitors (chemically related BAY1436032, AG-881, IDH1-305, IDH1-125 and IDH1-146) in complex with mutant IDH1 have shown that they bind to allosteric pockets, inducing a conformational change and consequently inhibit the catalytic activity.12, 17–19 Until now there is no approved or clinically active inhibitor, which binds to the active site of mutant IDH1. By computational screening of approximately 500,000 compounds, we have previously identified the IDH1 mutant-specific inhibitor HMS-101, which has shown efficacy towards IDH1 mutant cells in vitro.20

In this study, we evaluated the antileukemic effect of HMS-101 in a syngeneic mutant IDH1 mouse model and a patient-derived human AML xenograft model as well as performed biochemical and structural studies to evaluate the molecular mechanism of this compound. From this study, we conclude that HMS-101 binds to the active site of mutant IDH1, which is different from other IDH1 inhibitors, inhibits cellular proliferation and induces differentiation in IDH1 mutant leukemia cells.

Materials and methods

IDH activity assay

The enzymatic activity of pure IDH proteins was assessed by measuring the rate of consumption or production of NADPH spectrophotometrically at 340 nm wavelength. A reaction mixture was prepared with 100 mM Tris, pH-7.4, 1% BSA and 5 mM of MnCl2 along with 250 μM NADPH as the co-factor for IDH1 and IDH2 mutants and 50 mM HEPES, pH-7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM of MgCl2 along with 1 mM NADP for IDH1 and IDH2 wt enzyme catalysis. Reactions containing 500 nM of mutant IDH1 or mutant IDH2 proteins were initiated by adding 250μM α-ketoglutarate as a substrate, whereas reactions containing 3 nM of wt IDH1 or wt IDH2 proteins were initiated upon addition of 4 mM isocitrate. All chemicals for the activity assays were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). Efficacy of the drug was tested by incubating IDH1 proteins with increasing concentrations of HMS-101 or PBS (control) for 30 minutes prior to the experiment. Assays were performed with Multiskan FC (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and the specific activity was calculated from the slope value obtained from kinetic reactions.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

Crystals of the IDH1mut-HMS-101 complex were obtained by co-crystallization of the purified IDH1mut protein with a concentration of 10 mg/ml in the presence of 2 mM HMS-101 by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C. The mixture was incubated for 30 minutes on ice and subsequently mixed with an equal volume of the reservoir solution (0.2 M di-ammonium citrate, 20% (w/v) PEG 3350) without the addition of NADP or α-ketoglutarate. The crystals were transferred to a cryoprotection solution containing reservoir solution mixed with 2 mM HMS-101 and additional 25% ethylene glycol, and subsequently flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at beamline PROXIMA-1, Synchrotron SOLEIL, Gif-sur-Yvette, France. The dataset was processed using XDS,21 and the structure was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser22 of Phenix23 and the structure of IDH1wt (pdb: 1T09)8 as the search model. Structure refinement was carried out with Phenix and a random 5% of the data was excluded for cross-validation. Model building and validation was done using Coot.24 The final coordinates were stored in the protein database25 with the identification code 6Q6F.

In silico screening of IDH1mut inhibitors, compound preparation, retroviral vectors and infection of primary bone marrow cells, cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant IDH1 mutant proteins, microscale thermophoresis, 2-hydroxyglutarate quantification, patient samples, clonogenic progenitor assay, antibodies for immunophenotyping and morphologic analysis, cell culture and treatment, cell viability and cell counts, pharmacokinetic and toxicity analysis of HMS-101, bone marrow transplantation, treatment and monitoring of mice, quantitative RT-PCR, immunoblotting and statistical methods are described in detail in Supplementary Materials.

Results

Validation of candidate inhibitors of mutant IDH1

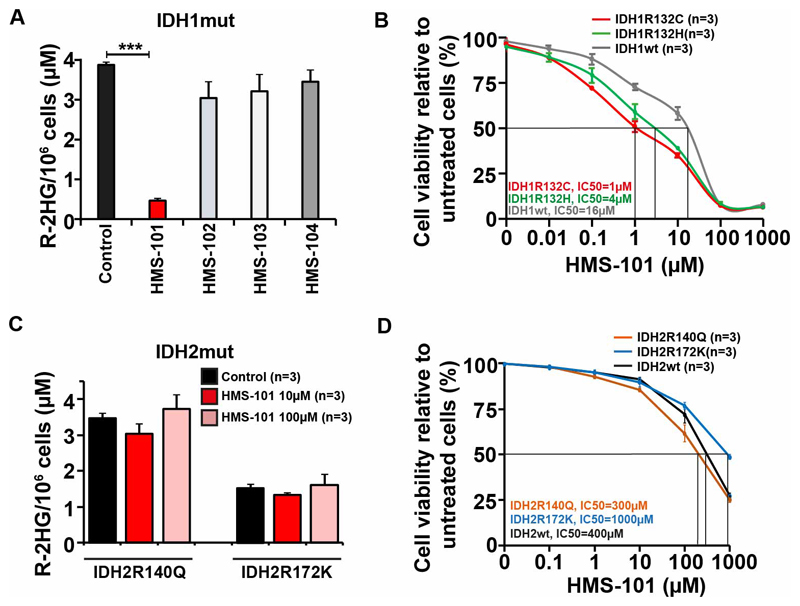

A parallelized, high-throughput computational screening approach of ~1 million compounds from the Zinc database26 against mutant IDH1, allowed us to identify four promising candidates for the specific inhibition of IDH1mut (Supplementary Table S1). These compounds showed high binding energies against the high-resolution IDH1mut crystal structure (pdb: 3INM)3 and a marked preference towards mutant IDH1 over wildtype, when re-docked against an IDH1wt crystal structure (pdb: 1T0L)8. We used a subset of the lead-like library of the Zinc database to ensure preferable pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds. Both, limiting the search area during computational docking to the isocitrate binding site, as well as covering both the isocitrate and NADP binding sites, suggested favorable binding of these ligands to the isocitrate binding pocket on IDH1mut with predicted binding energies in the range of -12 kcal/mol, giving computed ligand efficiencies (LE) of 0.5 to 0.8. In contrast, a second population was found for the larger search area with smaller parts of the ligands overlapping with the NADPH binding site, featuring slightly lower predicted overall binding energies. For both identified binding sites and all four compounds, the computed affinities towards IDH1mut were markedly higher than those obtained with IDH1wt. The on-target efficacy of these candidate inhibitors was evaluated by their effect on R-2HG levels, which is specifically produced by mutant IDH1. Murine hematopoietic bone marrow cells were transformed with HoxA9 and the IDH1R132C mutant as described previously,20 and were treated with the four candidate IDH1 inhibitors for 72 hours. The concentration of R-2HG was significantly reduced by HMS-101 and only slightly decreased by HMS-102, HMS-103 and HMS-104 (Figure 1A and Supplementary figure S1A). We further evaluated their effect on cell viability in murine HoxA9+IDH1mut cells expressing either the IDH1R132C or the IDH1R132H mutation. HMS-101 reduced the IC50 for both mutation types compared to IDH1 wildtype overexpressing cells, suggesting broad activity against different types of IDH1 mutations (Figure 1B). However, HMS-101 did not inhibit R-2HG production in HoxA9 immortalized mouse bone marrow cells expressing IDH2 R140Q and R172K mutants (Figure 1C and Supplementary figure S1B) and the cellular IC50 of HMS-101 was 300 to 1000 fold higher in IDH2 R140Q (300μM), IDH2 R172K (1000μM) and IDH2wt (400 μM) cells compared to IDH1mut cells, indicating the specificity of HMS-101 towards mutant IDH1 (Figure 1D). In order to determine the binding affinity of HMS-101 to IDH1mut, we used microscale thermophoresis measurements (Supplementary Figure S1C). The binding affinity of HMS-101 toward IDH1mut in the absence of substrate and cofactor is in the low micromolar range (Kd: IDH1R132H 14.1 μM). In the presence of NADPH and αKG, the Kd of HMS-101 is shifted to higher values (Kd: IDH1R132H 445.9 μM and IDH1R132C 191.9 μM), indicating that HMS-101 competes with either NADPH or α-KG for binding to mutant IDH1. The other candidate inhibitors showed no differential cytotoxic effect in IDH1mut compared to IDH1wt cells (Supplementary Figure S2A-C). We, therefore, selected HMS-101 for further characterization.

Figure 1. Validation of candidate inhibitors of mutant IDH1.

A) Concentration of R-2HG per million cells in mouse HoxA9+IDH1mut transduced mouse bone marrow cells incubated with 10 μM of HMS-101, HMS-102, HMS-103 and 100 μM of HMS-104 or DMSO for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n=3).

B) IC50 of HMS-101 in HoxA9+IDH1wt, HoxA9+IDHmut R132C and HoxA9+IDH1mut R132H cells treated for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n=3).

C) Concentration of R-2HG per million cells in mouse HoxA9+IDH2mut transduced mouse bone marrow cells incubated with 10 μM and 100 μM of HMS-101 or DMSO for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n=3).

D) IC50 of HMS-101 in HoxA9+IDH2wt, HoxA9+IDH2 R140Q and HoxA9+IDH2 R172K cells treated for 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n=3).

***P<0.001

HMS-101 inhibits the enzymatic activity of mutant IDH1

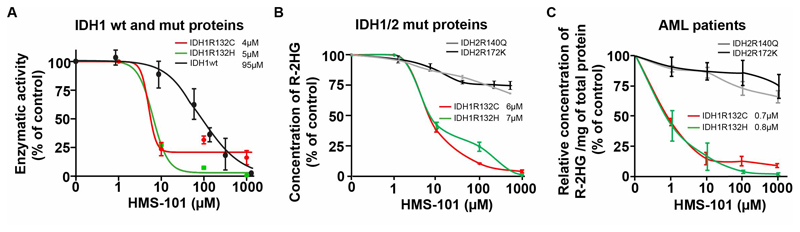

We purified His-tagged wildtype and mutant IDH1 proteins (IDH1mutR132C and IDH1mutR132H) from the BL21DE3 bacterial strain (Supplementary Figure S3). The preferential reactivity of the wildtype IDH1 protein with isocitrate and of the mutant IDH1 protein with αKG was confirmed in activity assays in vitro (Supplementary Figure S4). While IDH1wt and IDH2wt enzymatic activities were only affected at higher compound concentrations (IC50: IDH1wt 95 μM, Figure 2A, and IDH2wt 110 μM, Supplementary Figure S5), HMS-101 selectively inhibited the enzymatic activity of both IDH1 mutation types in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 4 μM (IDH1mutR132C) and 5μM (IDH1mutR132H), accounting for a 19 and 24-fold selectivity over IDH1wt, respectively. The conversion from αKG to R-2HG by the IDH1mut pure protein in a cell free solution was also efficiently inhibited by HMS-101 (IC50: IDH1mutR132C 6μM, IDH1mutR132H 7 μM), however, the IC50 of HMS-101 was not reached until a concentration of 1mM for the IDH2 mutant protein (Figure 2B). We validated the specificity towards mutant IDH1 by treating primary AML cells from IDH1 and IDH2 mutated patients. R-2HG was reduced in a dose dependent manner in IDH1 mutant but not in IDH2 mutant AML patients (IC50: IDH1mut R132C 0.7 μM, IDH1mut-R132H 0.8 μM, Figure 2C). While R-2HG production was efficiently inhibited within 24 hours, viability and cell counts of primary AML cells were hardly affected within this short time frame (Supplementary Figure S6A-B). Thus, HMS-101 preferentially interferes with the enzymatic activity of mutant IDH1.

Figure 2. HMS-101 inhibits the enzymatic activity of mutant IDH1.

(A) Inhibition of IDH1mut R132C or IDH1mut R132H enzymatic activity measured by the rate of consumption of NADPH and IDH1wt activity by the rate of production of NADPH in the presence of increasing concentrations of HMS-101 compared to the PBS treated control (mean ± SEM, n=3).

(B) Inhibition of R-2HG production by IDH1mut-R132C, IDH1mut-R132H, IDH2mut-R140Q and IDH2mut-R172K proteins in the presence of increasing concentrations of HMS-101 compared to PBS treated control (mean ± SEM, n=3)

(C) Concentration of R-2HG/mg protein in primary human AML cells harboring different IDH1 and IDH2 mutations 24 hours after HMS-101 treatment, calculated as percentage of PBS control treated cells. IC50 values for mutant IDH1 are provided in the graph (mean ± SEM, n=3).

X-ray diffraction revealed binding of HMS-101 in the active site of mutant IDH1

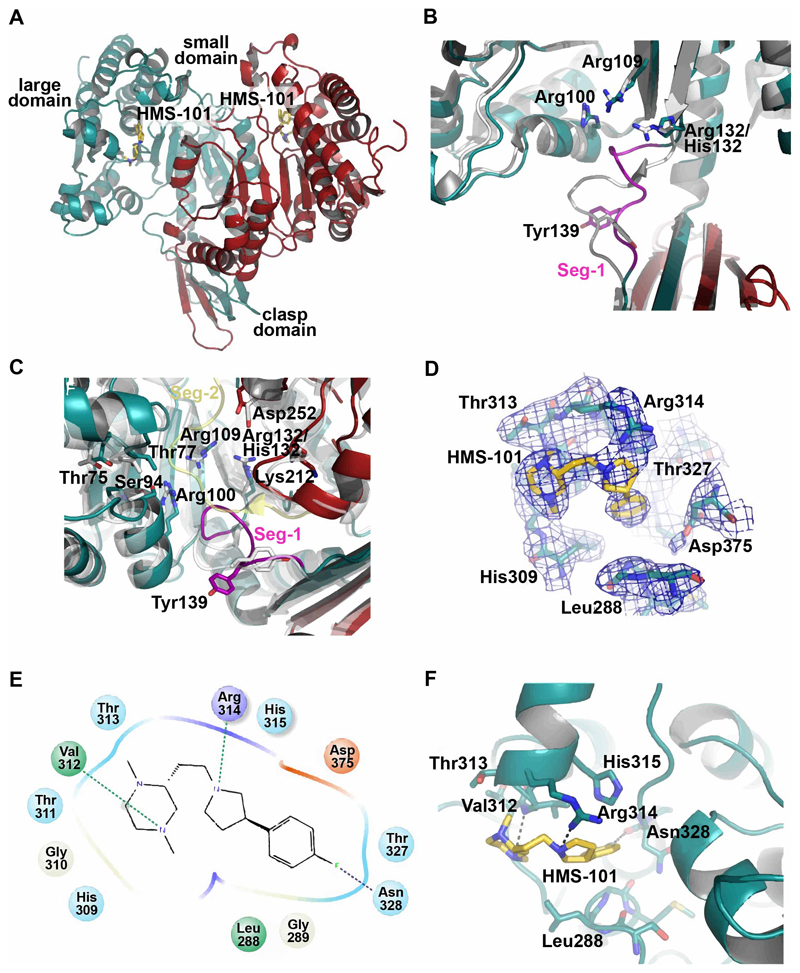

To verify the predicted binding of HMS-101 to the active site and to determine the detailed binding mode of the inhibitor, we co-crystallized IDH1mutR132H with HMS-101 in the absence of substrate or co-factor, and solved the structure by molecular replacement to a resolution of 3.3 Å (Fig. 3A). Statistics for diffraction data and structure refinement are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The overall fold of the IDH1mut-HMS-101 complex resembles the reported IDH1mut crystal structures, featuring a mutated homodimeric structure with an open/quasi-open active site conformation in the subunits and a width of the active site entrance of 19.7 Å and 17.0 Å (measured between residues 76 and 250 of the second subunit), respectively. Accordingly, the back clefts are closed with widths of 11.1 Å and 11.3 Å (measured between residues 199 and 342). The large domains of the subunits show the typical Rossmann fold, while the small domains fold in an α/β sandwich, and the clasp domains of the two subunits form together two four-stranded β-sheets. As has been seen before in crystal structures of IDH1mut in the open/quasi-open conformation (pdb: 3MAP and 3MAR)9, the regulatory segment (seg-2, residues 271 to 286) in the active site is disordered and was not observable in the obtained HMS-101 complex crystal structure. This important structural segment, together with the hinge segment (seg-1, residues 134 to 141) undergoes substantial conformational rearrangements during the transition from the open conformation to the catalytically competent closed conformation8. Seg-1 could be resolved in our structure and adopts a slightly different conformation as compared to IDH1wt in the open or closed state, with changes in the Tyr139 conformation (pdb: 1T09 and 1T0L, Figure 3B)8.

Figure 3. Crystal structure of HMS-101 bound to the active site of mutant IDH1.

(A) Overview of the co-crystallized structure of mutated IDH1 in complex with HMS-101 in a cartoon representation. The subunits of mutated IDH1 are depicted in cyan and red, and the inhibitor was found in both subunits.

(B) Close-up view of segment-1 (seg-1, purple), featuring a slightly different conformation with rearrangements of the catalytically important residue Tyr139, as compared to the IDH1wt crystal structure (pdb: 1T09, transparent grey structure).

(C) Close-up view on the active site showing rearrangements of the active site residues that are involved in the enzymatic activity. Note the slightly more open active site due to conformational changes of the large domain (cyan). The subdomains are colored cyan and red, seg-1 and seg-2 (of IDH1wt crystal structure, pdb: 1T09) are shown in purple and yellow, respectively. For comparison, the IDH1wt crystal structure is depicted as transparent grey structure.

(D) The 2Fo-Fc density map of HMS-101 and surrounding residues of the binding site. The map was contoured at 1.0 σ.

(E) Interaction diagram, showing the HMS-101 binding site and contact residues. Green dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds and purple dashed lines show halogen bonds. Color code: green: unpolar residues, red: negatively charged residues, purple: positively charged residues, cyan: polar residues, beige: glycine residues.

(F) Close-up view of the HMS-101 binding site with contact residues shown as sticks. Dashed lines indicate favourable interactions with the protein.

Compared to the known IDH1mut crystal structure in the presence of α-KG and NADPH (pdb: 3MAP), the large domains in the HMS-101-bound structure of both subunits are moved slightly outwards with root mean square deviations (RMSD) of 1.94 and 2.19 Å to adopt a slightly more open active site. Several rearrangements of active site residues were observed upon ligand binding, including residues Ser94, Arg100, Arg109, and Lys212 (Figure 3C). The ligand HMS-101 binds to both subunits in a compact, bent conformation, and is nestled to a site that partially overlaps with the NADPH binding site in other known IDH1 crystal structures (Fig 3A and 3D). Favorable interactions with protein residues are formed between the piperazine ring of HMS-101 and the main chain nitrogen of Val312, as well as the pyrrolidin ring and the side chain of Arg314 (Fig. 3E and 3F). In addition, a halogen bond between the fluorophenyl and Asn328 is found, and a number of hydrophobic interactions with residues Leu288, Gly310, and Val312 stabilize the binding. The total protein surface interaction area in contact with HMS-101 comprises approximately 419 Å. Thus, our data support binding of HMS-101 to the active site of mutant IDH1.

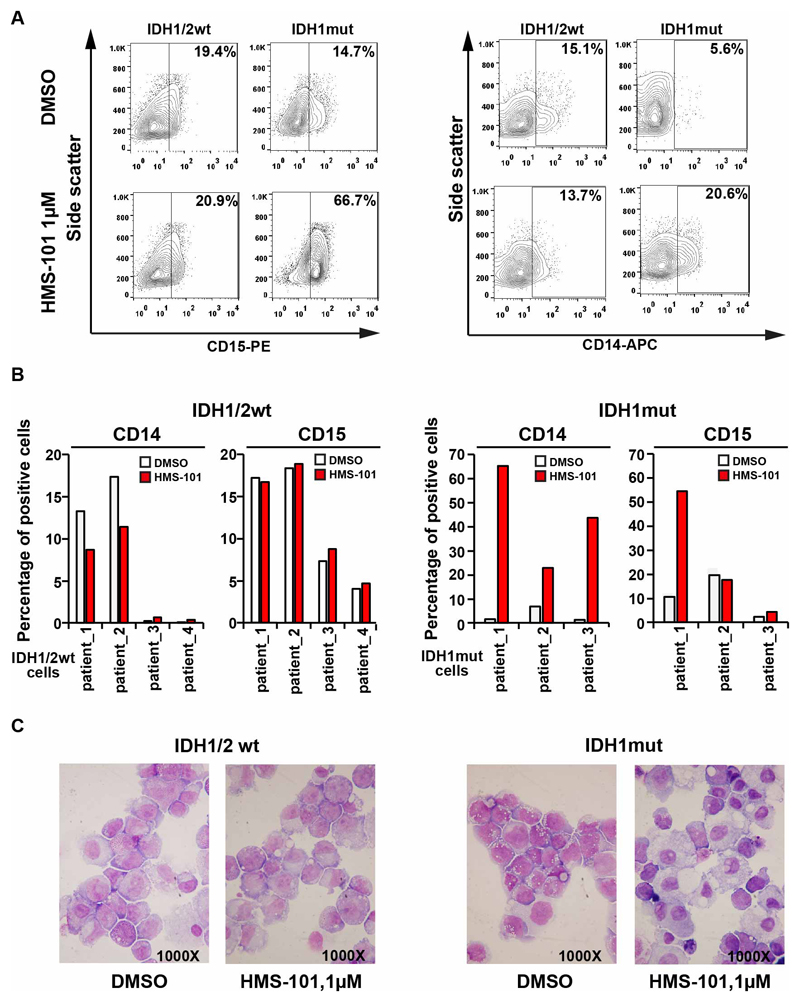

HMS-101 inhibits proliferation and induces differentiation in primary human AML

We determined the effects of treatment with HMS-101 in primary human AML cells with wildtype or mutant IDH1 on cellular differentiation. IDH1mut human AML cells that were cultured in suspension medium ex vivo showed marked upregulation of the myeloid differentiation markers CD15 and/or CD14 (Figure 4A and 4B). Viability and cell counts of human AML cells were more efficiently inhibited by HMS-101 than by control treatment in IDH1mut cells (Supplementary Figure S7A-B). In HMS-101 treated IDH1mut AML we observed morphologic changes consistent with monocytic differentiation (Figure 4C), demonstrating that HMS-101 induces myeloid differentiation in AML cells. No morphological changes suggestive of granulocytic or monocytic differentiation were observed in wildtype IDH1 AML cells treated with DMSO or HMS-101 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. HMS-101 inhibits proliferation and induces differentiation in primary human AML.

(A) Representative FACS plots from IDH1/2wt and IDH1mut AML patient cells showing proportions of CD14+ and CD15+ cells after treatment with either 1μM HMS-101 or DMSO for 14 days ex vivo.

(B) Percentages of CD14+ or CD15+ cells in four IDH1wt human AML patients cells (left) and three IDH1mut human AML patients cells (right) after treatment with either 1 μM HMS-101 or DMSO for 14 days ex vivo. Two IDH1mut patients carry R132C and one an R132H mutation.

(C) Morphology of bone marrow cells from IDH1wt and IDH1mut AML patients treated with either 1 μM HMS-101 or DMSO for 14 days ex vivo (1000x magnification).

HMS-101 inhibits proliferation, induces myeloid differentiation and prolongs survival in leukemic mice in vivo

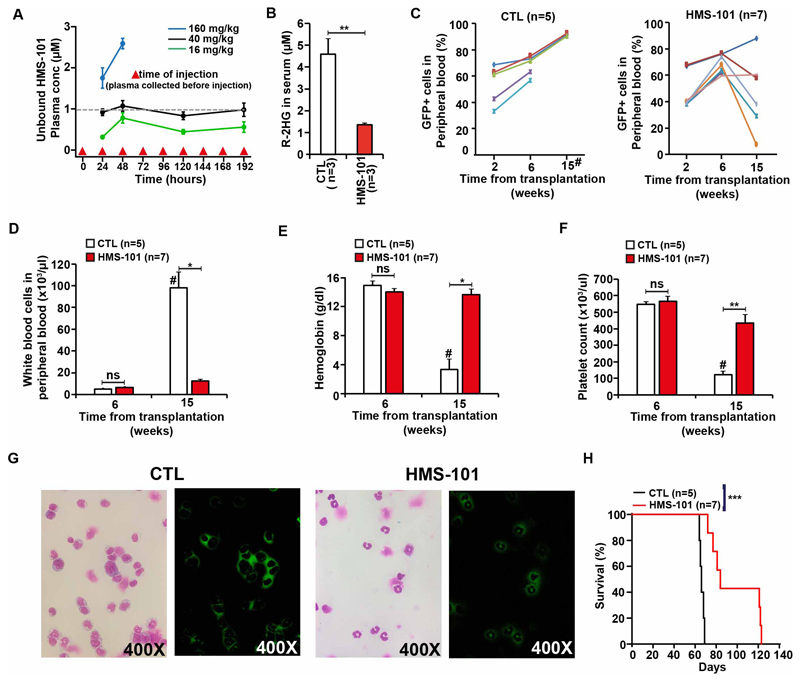

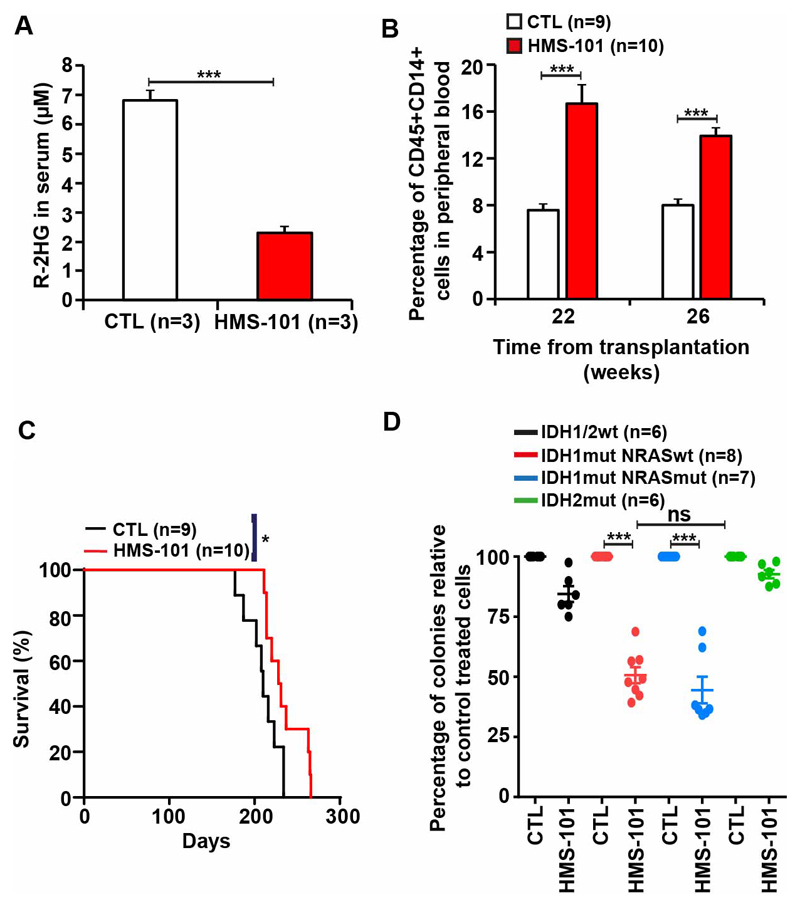

The maximum tolerated dose of HMS-101 was identified by treating C57BLJ/6 mice with varying doses of HMS-101. A dose of 40mg/kg HMS-101 intraperitoneally once daily produced plasma levels equivalent to the in vitro IC50 in HoxA9 IDH1mut cells 20 (Figure 5A) and was well tolerated in mice with no visible signs of toxicity on body weight, complete blood counts, spleen weight and serum chemistry (Supplementary Figure S8A-I and Supplementary Table S3). HMS-101 was further evaluated for its antileukemic effects in vivo in a previously described mouse model induced by co-expression of HoxA9 and IDH1mutR132C.20 HMS-101 was applied intraperitoneally once daily starting on day 5 after transplantation and continued until death at a dose of 40 mg/kg. After eight weeks of treatment, R-2HG was significantly reduced in the serum of HMS-101 treated compared to solvent treated mice (Figure 5B). While leukemic engraftment in peripheral blood continuously increased in solvent treated mice, it decreased in 5 of 7 mice after week 6 of transplantation (Figure 5C). At 15 weeks or at death of the mice that had died before week 15 WBC count was significantly lower, and hemoglobin and platelet count were significantly higher in HMS-101 treated mice compared to control mice (Figure 5D-F). Fifteen weeks after transplantation HMS-101 treated mice showed mostly differentiated GFP-positive/IDH1mut-transduced cells (neutrophils) in peripheral blood, while control treated mice had mostly undifferentiated GFP-positive/IDH1mut-transduced myeloid progenitor cells in peripheral blood (Figure 5G). Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood cells at 15 weeks after transplantation confirmed that HMS-101 shifted the myeloid cells from the more immature phenotype CD11b+Gr1- to the more mature phenotype CD11b+Gr1+ (Supplementary Figure S9). Importantly, these effects of HMS-101 attributed to differentiation induced a significant survival benefit with a median survival of 66 days for control treated and of 84 days in HMS-101 treated mice (Figure 5H and Supplementary Figure S10). HMS-101 was also evaluated in a PDX model of an IDH1 mutated AML patient. This patient had IDH1 p.R132C, NRAS p.Q61R, ETV6 p.R103SfsTer9, PTPN11 p.S502P, ASXL1 p.E947Ter, RUNX1 p.R169KfsTer44, and EZH2 p.P527S mutations. Treatment was started with HMS-101 or solvent intraperitoneally once daily starting on day 45 after transplantation and continued until death at a dose of 40 mg/kg body weight. At 18 weeks, the R-2HG concentration in serum declined by 2.9-fold in HMS-101 treated mice (Figure 6A) and at 22 and 26 weeks after transplantation, the proportion of CD14, a marker of monocytic differentiation, on human cells was significantly higher in HMS-101 treated mice compared to controls (Figure 6B). Median survival was significantly prolonged by 20 days in HMS-101 treated mice (median survival 210 vs 230 days, Figure 6C). In an independent, second PDX model, which harbored IDH1 p.R132H, DNMT3A p.R882H, PTPN11 p.A72T, and NPM1 p.T288CfsTer12 mutations, the percentage of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood of mice increased in vehicle-treated animals but was essentially absent in HMS-101 treated mice (Supplementary Figure S11A). In an independent third PDX model, NSG mice were transplanted with primary IDH1/IDH2 wt, NPM1 p.W288CfsTer12 and TET2 p.G1931D mutant AML cells. Both HMS-101 and vehicle-treated mice had similar percentages of human CD45+ cells in peripheral blood of mice (Supplementary Figure S11B). There was no significant difference between the number of colonies formed by IDH1mut/NRASwt and IDH1mut/NRASmut primary AML cells in the presence of HMS-101 compared to control treated cells, suggesting that NRASmut is not predictive of response to HMS-101. Further, HMS-101 did not inhibit the colony formation of IDH2 mutant AML patient cells indicating specificity towards mutant IDH1 (Figure 6D).

Figure 5. HMS-101 inhibits proliferation, induces myeloid differentiation and prolongs survival in leukemic mice in vivo.

(A) Unbound HMS-101 plasma concentrations in C57BL6/J mice treated with a daily dose of 16, 40 and 160 mg/kg HMS-101 for 9 days. Plasma was collected before the next injection on day 1, day 2, day 7 and day 8 (mean ± SEM of 5 animals/dose). The dashed line indicates the in vitro IC50 in HoxA9 IDH1mut cells.

(B) Absolute concentration of R-2HG in the serum of mice transplanted with HoxA9 IDH1mut cells and treated with HMS-101 at a dose of 40mg/kg for 8 weeks (mean ± SEM).

(C) Engraftment of HoxA9 IDH1mut cells in peripheral blood of mice treated with either vehicle (left) or HMS-101 at a dose of 40mg/kg at the indicated time points (mean± SEM).

(D) White blood cell count, (E) hemoglobin level, and (F) platelet count in peripheral blood at different time points after the start of treatment with vehicle or HMS-101 at a dose of 40mg/kg (mean ± SEM).

(G) Morphology and fluorescence of peripheral blood cells from HoxA9+IDH1mut transplanted mice treated with vehicle (left) or HMS-101 (right) at 15 weeks after treatment (400X original magnification). Mutant IDH1 was expressed from a retroviral vector that co-expresses GFP. Thus, GFP positive cells indicate IDH1 mutant leukemic cells.

(H) Survival of HoxA9+IDH1mut transplanted mice treated with either vehicle or HMS-101.

* P<0.05, **P<0.01, *** P<.001

# week 15 after transplantation or at death if the mouse died before week 15 due to leukemia

Figure 6. HMS-101 induces differentiation in primary IDH1 mutant AML cells.

(A) Absolute concentration of R-2HG in the serum of PDX-IDH1R132C mice treated with HMS-101 at a dose of 40mg/kg or vehicle for 18 weeks (mean± SEM).

(B) Percentage of human CD14+ cells in peripheral blood of PDX-IDH1R132C mice at different time points with either vehicle or HMS-101 at dose of 40mg/kg (mean ± SEM).

(C) Survival of PDX-IDH1R132C transplanted mice treated with either vehicle or HMS-101.

(D) Colony forming cell assay of IDH1/2 wt, IDH1mut/NRASwt, IDH1mut/NRASmut and IDH2mut primary cells from AML patients treated with HMS-101 relative to DMSO-treated cells (mean ± SEM).

* indicates P<.05, *** indicates P<.001

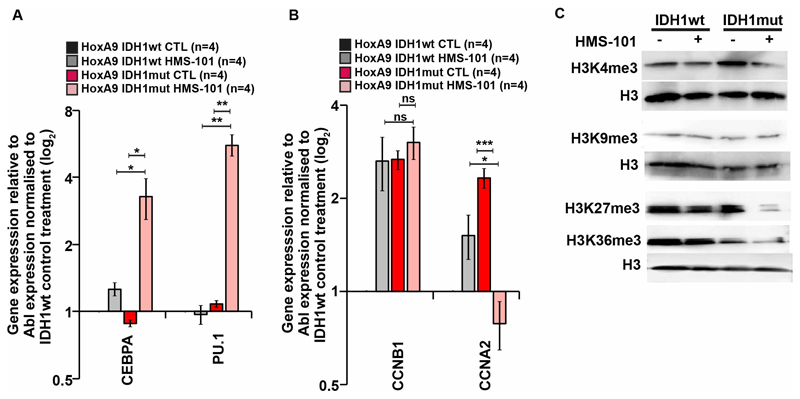

HMS-101 induces expression of differentiation genes, inhibits cell cycle associated genes and restores histone methylation in HoxA9+IDH1mut cells

Murine HoxA9+IDH1mut cells were treated with HMS-101 or solvent for 9 days to evaluate the impact of HMS-101 on gene expression. CEBPA and PU.1 are critical transcription factors for granulocytic and monocytic differentiation, respectively. Both genes were strongly upregulated upon HMS-101 treatment in IDH1mut but not IDH1wt cells (Figure 7A). The cell cycle regulator CCNA2, but not CCNB1 was significantly downregulated in HMS-101 treated IDH1mut cells (Figure 7B), suggesting that the inhibitor induces differentiation and inhibits cell cycle, as reported for other IDH1 inhibitors before.12, 13, 27 As R-2HG inhibits several histone demethylases like the H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 histone demethylases KDM4A, KDM4C,5, 27–29 we evaluated the effect of HMS-101 on histone methylation. H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 were increased in IDH1mut cells compared to IDH1wt cells. This increase in H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 methylation was efficiently reduced by HMS-101 in IDH1mut cells with no effect in IDH1wt cells (Figure 7C). Additionally, H3K36me3 methylation, which is reported to be increased in IDH1mut knock-in mice,28 also declined after treatment with HMS-101 in IDH1mut cells but not in IDH1wt cells (Figure 7C). These changes in gene expression and histone methylation were accompanied by a marked reduction in cell viability and absolute cell counts in IDH1mut cells treated with HMS-101 (Supplementary Figure S12 A-B). In summary, HMS-101 induces differentiation, inhibits cell cycle and reverses aberrant histone methylation in IDH1mut leukemias.

Figure 7. HMS-101 induces expression of differentiation genes, inhibits cell cycle associated genes and restores histone methylation in HoxA9+IDH1mut cells.

(A) Gene expression levels of differentiation-inducing genes CEBPA and PU.1 in in vitro cultured HoxA9 cells transduced with IDH1wt or IDH1mut and treated with either vehicle (CTL) or 1 μM HMS-101 for 9 days. Gene expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR relative to the housekeeping gene Abl1 and was normalized to gene expression in IDH1wt vehicle treated cells (mean ± SEM).

(B) Gene expression levels of cell cycle genes genes CCNB1 (Cyclin B1) and CCNA2 (Cyclin A2) as described above (mean ± SEM).

(C) Western blot of histone H3 trimethylation levels at residues H3K4, H3K9, H3K27 and H3K36 in HoxA9 IDH1wt and HoxA9 IDH1mut cells treated with 1 μM HMS-101 for 9 days.

* indicates P<.05, ** indicates P<.01, *** indicates P<.001, ns, non significant

Discussion

We characterized the unique properties of the IDH1 inhibitor HMS-101, which competitively inhibits mutant IDH1 and binds in proximity of the NADPH binding site in the active site of the enzyme, thereby inhibiting the conversion of α-ketoglutarate (KG) to R-2HG. HMS-101 is active in vivo, supresses R-2HG production, induces myeloid differentiation and prolonges survival in syngeneic and IDH1mut xenograft mouse models.

IDH1 is one of the few enzymes, which is capable of a novel enzymatic catalysis as a consequence of a single amino acid mutation in the active center, resulting in incomplete catalytic product formation of R-2HG3. Elevated levels of R-2HG in the cells result in disruption of α-ketoglutarate dependent enzymatic functions because of structural similarity resulting in epigenetic changes leading to IDH1 induced tumors.5, 10, 30 Several allosteric IDH1 inhibitors are in the pipeline to deliver a targeted therapy including a pan IDH1/IDH2 mutant inhibitor (AG-881).12, 17–19

By computational screening of around 0.5 million compounds, we identified IDH1mut inhibitor HMS-101, which has a marked preference towards mutant IDH1 over wildtype IDH1 and either mutant or wildtype IDH2. We observed inhibition of IDH1/2 wildtype enzymatic activity at higher concentrations of HMS-101. Jiang and colleagues showed that IDH1 and IDH2 proteins are required to generate NADPH in the mitochondria, enabling cells to mitigate mitochondrial ROS and maximize growth.31 High concentrations of HMS-101 may interfere with the oxidative function of IDH1/2 thus reducing NADPH and increasing reactive oxygen species in the mitochondria, which inhibits cell growth. The co-crystallization of IDH1mut-R132H in the presence of HMS-101 showed that the inhibitor occupied in part the NADPH binding site within both subunits of the enzyme. Both, polar and hydrophobic interactions were found to stabilize the binding of HMS-101. In our crystal structure, the inhibitor is bound to the enzyme in a open/quasi-open active site conformation with the regulatory segments disordered, a characteristic that has been reported to be specific for mutated IDH1.9 Both, the regulatory and hinge segments experience substantial conformational transition to transfer IDH1 to the catalytically competent state. Binding of HMS-101 to the IDH1mut-specific open/quasi-open conformation might contribute to the preferred behaviour of HMS-101. The identified binding mode of HMS-101 is clearly different to other known, mostly allosteric IDH1 inhibitors, providing opportunity to explore its effect in cells with acquired resistance to clinical inhibitors. Inhibitors like IDH1-146, a BAY1436032-like inhibitor and GSK321A bind to the same allosteric pocket of the enzyme, leading to conformational changes in the enzyme.32 Of the three inhibitors mentioned, only BAY1436032 is bound to an allosteric region that is closer to the single amino acid mutation site His-132.32 Apart from allosteric inhibitors mentioned, IDH1 inhibitors like compound-1, ML-309, and Bis imidazole phenol were reported to bind to the metal ion binding site of IDH1mut-R132H.11, 33

In our study, we demonstrate that HMS-101 induces differentiation of HoxA9 immortalized IDH1mut cells in vivo in a syngeneic transplantation mouse model revealing the therapeutic perspective of the drug.20 Indeed, HMS-101 induced differentiation of primary IDH1 mutant AML cells, but not of cells from wildtype IDH1 patients. In addition, we found that treatment of xenografted NSG mice with the bioavailable HMS-101 resulted in reduced 2-HG levels in serum, decreased levels of leukemic blasts and prolonged survival of IDH1mut PDX mice in two different AML models. These results suggest the potential use of further optimized derivatives of HMS-101 in IDH1 mutant AML.

Previous studies have shown that IDH1 mutations result in global DNA and histone hypermethylation.5, 28, 30 We found that treatment with HMS-101 led to reduced levels of the H3K4me3, H3K27me3 and H3K36me3 methylation mark in HoxA9 immortalised IDH1 R132C expressing cells. Furthermore, HMS-101 induced the expression of CEBPA and PU.1. We have previously shown that the expression of several cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKNs) are downregulated in IDH1mut cells.20 CDKNs interact with a cyclin-CDK complex to block the kinase activity of cyclin dependent kinases (CDK). HMS-101 reduced the expression of cyclin A2, which activates CDK2 during S phase, and CDK1 during the transition from the G2 to the M phase, suggesting that HMS-101 interferes with cell cycle progression in IDH1mut cells.34

In summary, HMS-101 is a direct inhibitor of mutant IDH1 that is able to inhibit cellular proliferation and division and induce differentiation in IDH1mut cells. Structural studies validating the binding of HMS-101 to the active site of IDHmut imply that this compound can be further developed for therapeutic purposes with a distinct binding mechanism. Our study provides a rationale for the further development and investigation of competitive inhibitors of mutant IDH1 and the clinical evaluation of their therapeutic potential the treatment of patients with IDH1 mutant AML and other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the assistance of the Cell Sorting Core Facility of Hannover Medical School supported in part by the Braukmann-Wittenberg-Herz-Stiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. We would like to thank all participating patients and contributing doctors, the staff of the Central Animal Facility of Hannover Medical School, and Silke Glowotz, Nadine Kattre, Girish Rajendraprasad, Roopsee Anand, Martin Wichmann, Petra Baruch and Claudia Thiel for their support. This work was supported by an ERC grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (No. 638035), by grant 70112697 from Deutsche Krebshilfe; and DFG grants HE 5240/5-1, HE 5240/5-2, HE 5240/6-1 and HE5240/6-2.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.C., R.G, M.P., and M.H. conceived and designed the study. A.C., R.G., C.G., J.W.,T.K., M.M., A.K., K.G., R.S., B.O., E.S., H.B., D. GK., and K.B., collected the data. A.C., R.G., C.G., M.P., and M.H. analyzed and assembled the data. A.G. and M.H. collected patient samples and provided the patient data. A.C., M.P. and M.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the data and edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

A.C., M.P., and M.H. have filed an EP and US patent application for HMS-101 (based on PCT/EP2014/059898 with priority of 2013). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 9;374(23):2209–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner K, Damm F, Gohring G, Gorlich K, Heuser M, Schafer I, et al. Impact of IDH1 R132 mutations and an IDH1 single nucleotide polymorphism in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: SNP rs11554137 is an adverse prognostic factor. J Clin Oncol. 2010 May 10;28(14):2356–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009 Dec 10;462(7274):739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross S, Cairns RA, Minden MD, Driggers EM, Bittinger MA, Jang HG, et al. Cancer-associated metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate accumulates in acute myelogenous leukemia with isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations. J Exp Med. 2010 Feb 15;207(2):339–344. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012 Mar 22;483(7390):474–478. doi: 10.1038/nature10860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010 Dec 14;18(6):553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi A, Araujo Cruz MM, Jyotsana N, Sharma A, Goparaju R, Schwarzer A, et al. Enantiomer-specific and paracrine leukemogenicity of mutant IDH metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate. Leukemia. 2016 Aug;30(8):1708–1715. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X, Zhao J, Xu Z, Peng B, Huang Q, Arnold E, et al. Structures of human cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase reveal a novel self-regulatory mechanism of activity. J Biol Chem. 2004 Aug 6;279(32):33946–33957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang B, Zhong C, Peng Y, Lai Z, Ding J. Molecular mechanisms of "off-on switch" of activities of human IDH1 by tumor-associated mutation R132H. Cell Res. 2010 Nov;20(11):1188–1200. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C, et al. An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013 May 3;340(6132):626–630. doi: 10.1126/science.1236062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M, Pragani R, Popovici-Muller J, Gross S, Thorne N, Salituro F, et al. ML309: A potent inhibitor of R132H mutant IDH1 capable of reducing 2-hydroxyglutarate production in U87 MG glioblastoma cells. Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okoye-Okafor UC, Bartholdy B, Cartier J, Gao EN, Pietrak B, Rendina AR, et al. New IDH1 mutant inhibitors for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Chem Biol. 2015 Nov;11(11):878–886. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaturvedi A, Herbst L, Pusch S, Klett L, Goparaju R, Stichel D, et al. Pan-mutant-IDH1 inhibitor BAY1436032 is highly effective against human IDH1 mutant acute myeloid leukemia in vivo. Leukemia. 2017 Oct;31(10):2020–2028. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, Mims AS, et al. Durable Remissions with Ivosidenib in IDH1-Mutated Relapsed or Refractory AML. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 21;378(25):2386–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiNardo CD, Schimmer AD, Yee KWL, Hochhaus A, Kraemer A, Carvajal RD, et al. A Phase I Study of IDH305 in Patients with Advanced Malignancies Including Relapsed/Refractory AML and MDS That Harbor IDH1R132 Mutations. Blood. 2016;128(22):1073–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watts JM, Baer MR, Lee S, Yang J, Dinner SN, Prebet T, et al. A phase 1 dose escalation study of the IDH1m inhibitor, FT-2102, in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(15_suppl):7009–7009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pusch S, Krausert S, Fischer V, Balss J, Ott M, Schrimpf D, et al. Pan-mutant IDH1 inhibitor BAY 1436032 for effective treatment of IDH1 mutant astrocytoma in vivo. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 Apr;133(4):629–644. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1677-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma R, Yun CH. Crystal structures of pan-IDH inhibitor AG-881 in complex with mutant human IDH1 and IDH2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018 Sep 18;503(4):2912–2917. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie X, Baird D, Bowen K, Capka V, Chen J, Chenail G, et al. Allosteric Mutant IDH1 Inhibitors Reveal Mechanisms for IDH1 Mutant and Isoform Selectivity. Structure. 2017 Mar 7;25(3):506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaturvedi A, Araujo Cruz MM, Jyotsana N, Sharma A, Yun H, Gorlich K, et al. Mutant IDH1 promotes leukemogenesis in vivo and can be specifically targeted in human AML. Blood. 2013 Oct 17;122(16):2877–2887. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-491571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabsch W. Automatic Processing of Rotation Diffraction Data from Crystals of Initially Unknown Symmetry and Cell Constants. Journal of applied crystallography. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007 Aug 1;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010 Feb;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010 Apr;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. Journal of chemical information and modeling. 2012 Jul 23;52(7):1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urban DJ, Martinez NJ, Davis MI, Brimacombe KR, Cheff DM, Lee TD, et al. Assessing inhibitors of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase using a suite of pre-clinical discovery assays. Sci Rep. 2017 Oct 6;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12630-x. 12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki M, Knobbe CB, Munger JC, Lind EF, Brenner D, Brustle A, et al. IDH1(R132H) mutation increases murine haematopoietic progenitors and alters epigenetics. Nature. 2012 Aug 30;488(7413):656–659. doi: 10.1038/nature11323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011 Jan 18;19(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, Walsh LA, Fang F, Yilmaz E, et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 2012 Mar 22;483(7390):479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang L, Shestov AA, Swain P, Yang C, Parker SJ, Wang QA, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature. 2016 Apr 14;532(7598):255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature17393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dang L, Su SM. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutation and (R)-2-Hydroxyglutarate: From Basic Discovery to Therapeutics Development. Annual review of biochemistry. 2017 Jun 20;86:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng G, Shen J, Yin M, McManus J, Mathieu M, Gee P, et al. Selective inhibition of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) via disruption of a metal binding network by an allosteric small molecule. J Biol Chem. 2015 Jan 9;290(2):762–774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.608497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992 Mar;11(3):961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.