Abstract

Background and aims

Cirrhosis leads to considerable morbidity and mortality, compromises quality of life, and often necessitates assistance in activities of daily living. An informal caregiver bears the psychological burden of coping with the needs of the patient and the knowledge of morbid prognosis of a loved one. This aspect is rarely recognized and almost never addressed in a clinical practice.

Methods

This cross-sectional study assessed the factors influencing psychological burden of cirrhosis on the caregivers in a predominantly lower-middle socioeconomic class Indian population. Patients underwent psychometric tests [Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES)], and questionnaires for quantifying caregiver burden [Perceived Caregiver Burden (PCB) and Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI)] and assessing depression [Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)] and anxiety [Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)] were administered.

Results

One hundred patients with cirrhosis [70% male, 27% with past hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and 53% with minimal HE] and their caregivers (66% women, 81% spouse, 26.51 years of mean relationship) were evaluated. Caregiver burden scores were higher in patients with previous overt HE than in those without previous overt HE [PCB (74.63 vs. 66.15, P = 0.001), ZBI (27.93 vs. 21.11, P = 0.023), BDI (11.63 vs. 8.96, P = 0.082), and BAI (11.37 vs. 8.12, P = 0.027)]. Similarly, caregivers of patients with minimal HE had higher caregiver burden that those of patients who did not have minimal HE [PCB (70.74 vs. 65.85, P = 0.027), ZBI (26 vs. 19.51, P = 0.015)]. Burden scores correlated well with each other and with liver disease severity scores and negatively correlated with socioeconomic status. Repeated hospital admissions, alcohol as etiology, and lower socioeconomic status were the independent predictors of caregiver burden.

Conclusion

Higher perceived burden is common in caregivers of patients with cirrhosis. Repeated hospital admissions, alcoholism, and lower socioeconomic status influence caregiver burden.

Keywords: cirrhosis, minimal hepatic encephalopathy, caregiver burden

Abbreviations: ANOVA, Analysis of Variance; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CI, Confidence interval; HE, Hepatic Encephalopathy; PCB, Perceived Caregiver Burden; PHES, Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality across the globe.1 Patients with advanced cirrhosis have a poor quality of life, restricted activities of daily living, and limited survival in the absence of liver transplant.2, 3 Consequently, in addition to a vigilant medical oversight, they often need considerable assistance from their informal caregivers (usually the spouse or a close family member). Moreover, a robust caregiver support for motivation and medication adherence is desirable for patients listed for transplant.4

Most patients with cirrhosis are middle-aged males,5 often being the breadwinners of the family. In the Indian context, this is compounded by the lower mean age of cirrhosis at diagnosis,6, 7 predominantly uninsured population, and limited state-funded support. Caregiver burden is associated with depression, anxiety, and caregiver burnout8, 9 and may even affect patient mortality.10 Yet, this is an often-ignored aspect of clinical medicine.

Feeling overburdened, depressed, and anxious is common in caregivers of patients with cirrhosis. Previous episodes of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), poor cognitive function, severe disease, recurrent hospital admissions, ongoing alcoholism, lower income, and poor social support predicted increased caregiver burden.9, 11, 12, 13 We evaluated the burden on the informal caregivers of patients with cirrhosis and the factors responsible for this burden in our population.

Methods

We included the caregivers of 100 patients with cirrhosis of liver attending the liver clinic at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, a tertiary care referral center in Northern India. Due consent was taken from the patients and their caregivers, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the institute (9666/PG-2Trg/2013/21794/95 dated 29/10/2015).

The patients aged between 18 and 70 years. We excluded patients with uncontrolled neuropsychiatric symptoms, those on psychoactive medications, and those who used illicit drugs or alcohol in the preceding 3 months. Patients with a recent (preceding 6 weeks) history of overt HE, hospitalization, or gastrointestinal bleeding and/or who used drugs affecting psychometric performances such as benzodiazepines and antiepileptic or psychotropic drugs were also excluded. We also excluded patients with renal impairment (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other malignancies and severe medical problems such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, or psychiatric disorders that could influence performance of neuropsychiatric tests.

Patient Data

Demographic profile, etiology, duration and severity of cirrhosis, past decompensations (hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, upper gastrointestinal bleed), hospital admissions, and the comorbidities of patient were recorded. Patients underwent assessment for minimal HE by Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES).14 In Indian version, the number connection test B has been replaced with figure connection test (FCT) because some patients are not familiar with English alphabets. PHES ≤ −5 was considered abnormal and diagnostic of minimal HE.15 A prevalidated socioeconomic scale for the Indian population (Modified Kuppuswamy scale) was used to assess the socioeconomic status.16

Caregivers were interviewed, and their demographic data, relationship with patient, years of relation were recorded. The following questionnaires were administered.

Perceived Caregiver Burden

The Perceived Caregiver Burden (PCB) is a validated 31-item scale for measuring caregiver burden. It includes five factors: (a) impact on finances, (b) feelings of abandonment, (c) impact on work schedule, (d) impact on health of caregiver, and (e) sense of entrapment. Scores range from 31 to 124, with higher scores indicating higher burden.17

Zarit Burden Interview

The 22-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was developed to measure subjective burden among caregivers of patients with dementia. Total scores range from 0 (low burden) to 88 (high burden). A score of 0–20 indicates no or minimal burden; 21–40, mild to moderate burden; 41–60, moderate to severe burden; and 61–88, severe burden. The ZBI has good construct validity and excellent internal consistency.18, 19

Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a validated 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory. It is one of the most used instruments for measuring the severity of depression. Scores between 0 and 9 indicate minimal depression; 10–18, mild depression; 19–29, moderate depression; and 30–63, severe depression. Higher total scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.20

Beck Anxiety Inventory

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory used for measuring the severity of an individual's anxiety. This inventory has been translated into Hindi and revalidated in the Indian context for application on students where only 20 items of the original inventory has been used.21

The summed scale ranges from 0 to 60. The higher value indicates higher level of anxiety. A total score of 0–18 is interpreted as “low’ level of anxiety, 19–32 as “moderate” level of anxiety, and 33–60 as “high” level of anxiety.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean [95% confidence interval (CI)], and categorical data as frequency (%). Descriptive analysis was performed. Normality was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables with normal distribution were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or t-test; variables that were not normally distributed were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Normative data among various groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis by Bonferroni test. Discrete variables were analyzed using χ2 test. Pearson's correlation and Spearman correlation were used to check correlation. Linear regression was carried out for PCB and ZBI score as outcomes, and those with significant regression (<0.05) were analyzed using stepwise multiple linear regression. Comparisons were made between patients with/without previous HE and those with/without minimal HE at the time of the study. All statistical analyses were performed two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23 (IBM Corporation) was used for statistical computations.

Results

Demographic Profiles and Baseline Parameters of Patients

We evaluated 250 patients with liver cirrhosis during January 2015 to December 2015. One hundred fifty patients were excluded because of the following reasons: current hepatocellular carcinoma, 38; overt HE, 45; recent variceal bleed, 42; renal dysfunction, 75; ongoing/recent infection, 64; active alcoholism, 10; and other reasons, 30 (other malignancies, dyselectrolytemia, seizure disorder, stroke, heart disease, age > 70 years). A total of 100 patients and their caregivers were included in the analysis. Most of the patients (70%) were males, and majority caregivers were females (66%). The median age of patients was 50 years [interquartile range (IQR) 41–57], with most patients (75%) having had a decompensating event in the past. About a quarter of the patients (27%) had past HE. Majority of the patients (73%) were not educated beyond high-school level. The etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol in most patients (44%) followed by viral (20%). The duration of cirrhosis (from diagnosis to the time of the study) was more than one year in 74% patients. Seventy-five percent of patients experienced at least one decompensating event, and 27% had a previous episode of HE. Minimal HE was present in 53% of these patients. Forty-four (44%) of these patients were employed at the time of the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Profiles and Baseline Parameters of All Patients.

| Patients (N = 100) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50 (41–57) |

| Sex (M:F) | 70:30 |

| Education (years) | 10 (8–15) |

| Employed | 44 (44%) |

| Duration of illness (months) | 33 (12–51) |

| Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score | 7 (6–9) |

|

41 (41%) |

|

40 (40%) |

|

19 (19%) |

| MELD score | 12 (9–16.5) |

|

39 (39%) |

|

49 (49%) |

|

12 (12%) |

| PHES | −6 (−11.5 to −2) |

| Minimal HE present | 53 (53%) |

| Kuppuswamy class | |

| Lower | – |

| Lower middle | 27 |

| Upper lower | 19 |

| Upper middle | 48 |

| Upper class | 3 |

| Etiology | |

| Alcohol related | 44 (44%) |

| HCV/HBV related | 20 (20%) |

| NASH related | 10 (10%) |

| Others | 26 (26%) |

| Caregivers | |

|---|---|

| Age | 46.8 ± 11.9 |

| Gender (male %) | 34% |

| Years of relationship | 26.5 ± 9.7 |

| Years of education | 10 (8–15) |

Education status

|

10 12 31 11 36 |

Relationship with the patient

|

81 8 6 3 2 |

Data expressed as median (IQR) or mean ± SD; numbers are expressed in percentage (%).

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus, MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PHES Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score.

The mean age of the primary caregivers was 46.8 (95% CI, 44.44–49.16) years, and 66% were women. Mean years of education was 10.3 years (95% CI, 9.3–11.29), with 36% being educated beyond high school. Mean relationship duration between the patient and caregiver was 26.51 (95% CI, 24.58–28.44) years. Most of the caregivers (81%) were spouses (Table 1). Forty-three (43%) caregivers had comorbidities at the time of enrollment: 13% had hypertension, 9% had diabetes, 7% had hypothyroidism, 4% had anxiety, and 3% had depression and were on medications.

Cognitive Testing

Fifty-three (53%) patients had minimal hepatic encephalopathy at the time of the study. The median PHES score of included patients was −6 (IQR, −11.5 to −2). Median number connection test time was 45 (IQR, 30.5–63) seconds, figure connection test time was 76.5 (42–124) seconds, serial dotting test time was 64 (48.5–87) seconds, digit symbol test score was 22 (66.5––32), line tracing time was 107 (86–140) seconds, and line tracing error score was 34 (18.5–61).

Impact of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Caregivers of patients who experienced previous HE demonstrated a higher level of burden in the form of significantly higher median PCB (74 vs. 64, P < 0.001) and ZBI (25 vs. 20, P = 0.014) scores. Similar observation was made in terms of anxiety and depression levels (median BDI score 12 vs. 6, P = 0.01; median BAI score 11 vs. 7, P = 0.008) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Impact of (A) past hepatic encephalopathy and (B) minimal hepatic encephalopathy on caregiver burden, anxiety, and depression scores. HE, hepatic encephalopathy; PCB, Perceived Caregiver Burden; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

Presence of minimal HE at the time of presentation also showed higher burden on their caregivers (median PCB scores 70 vs. 64, P = 0.02; ZBI 25 vs. 16, P = 0.007). However, there was no significant difference on the scores measuring depression and anxiety (median BDI score 10 vs. 6, P=NS; median BAI score 9 vs. 7, P=NS) (Figure 1B).

Impact of Other Complications of Cirrhosis

Presence of ascites in the patients was associated with a higher PCB score (71.34 vs. 65.17, P = 0.005); however, there was no difference in the PCB score between the caregivers of those with/without previous variceal bleeding (70.54 vs. 67.63, P = 0.241) and kidney injury (70.25 vs. 68.19, P = 0.55).

There was no significant difference in the ZBI score between the caregivers of patients with/without previous variceal bleeding (23.75 vs. 22.64, P = 0.711), ascites (25.23 vs. 20.38, P = 0.070), and kidney injury (23.75 vs. 22.84, P = 0.826).

Severity of Liver Disease

The caregiver burden was highest in Child C group, followed by Child B and Child A group [PCB (73.11 vs. 70.80 vs. 63.98, P = 0.002) and ZBI (26.53 vs. 26.15 vs. 18.17, P = 0.01)].

CTP score correlated with PCB score (Spearman ρ = 0.38, P < 0.001) and ZBI score (ρ = 0.29, P = 0.003). Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score also correlated well with PCB (ρ = 0.24, P = 0.015) and ZBI (ρ = 0.27, P = 0.022). However, these scores did not correlate significantly with depression and anxiety scores.

Etiology of Cirrhosis

Majority (44%) had alcohol as the underlying etiology. The burden score was higher in alcohol-related cirrhosis than in nonalcoholic etiology [PCB score (71.98 vs. 65.66, P = 0.004), ZBI (26.23 vs. 20.37, P = 0.028)]. But there was no significant difference in the depression and anxiety score [BDI (10 vs. 9.43, P = 0.679), BAI (10.36 vs. 7.93, P = 0.064)].

Comorbidities

The presence of common comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypothyroidism in patients with cirrhosis had no effect over the caregiver burden [PCB (67.28 vs. 69.18, P = 0.407), ZBI (22.36 vs. 23.33, P = 0.746), BDI (9.54 vs. 9.77, P = 0.869), and BAI (9.54 vs. 8.66, P = 0.513)].

Socioeconomic Status

Almost all (97%) of our patients belonged to the lower or middle socioeconomic class. The median monthly income of the patients was Rs. 15,850 (US$ 220) (IQR, Rs. 8000–35000).

Only 44% of the patients were working at the time of the study, 36% were jobless, and 20% had never worked. Of the 36 jobless patients, 23 had left the job after the diagnosis.

The Kuppuswamy score negatively correlated with the burden score PCB (ρ = −0.47, P < 0.001) and ZBI(ρ = −0.531, P < 0.001). However, no significant correlation was found with depression and anxiety scores [BDI (ρ = −0.115, P = 0.256) and BAI (r = −0.051, P = 0.611)].

Effect on Caregivers

Caregiver burden was assessed with the PCB and ZBI score. The median PCB score was 67.5(IQR, 62–77), and the median ZBI score was 23.5 (IQR, 13–30). Based on the ZBI score, 43% of caregivers had mild to moderate burden and 8% had moderate to severe burden.

Depression and Anxiety in Caregivers

The median BDI score was 8 (5–14), and the median BAI score was 8.5 (4–12.5). Three of the caregivers were already diagnosed cases of depression and were on antidepressants. Four were known case of anxiety disorder and were on medications and were thus excluded from the analysis.

Based on the BDI score, 7% were found to have moderate to severe depression, 8% had borderline depression, and 25% had mild depression. Similarly, based on the BAI score, 4% were found to have moderate anxiety. The PCB score correlated well with the ZBI (spearman ρ = 0.73, P < 0.01), BDI (ρ = 0.59, P=<0.01), and BAI (ρ = 0.46, P=<0.01). The BDI also correlated strongly with the BAI (ρ = 0.63, P < 0.01).

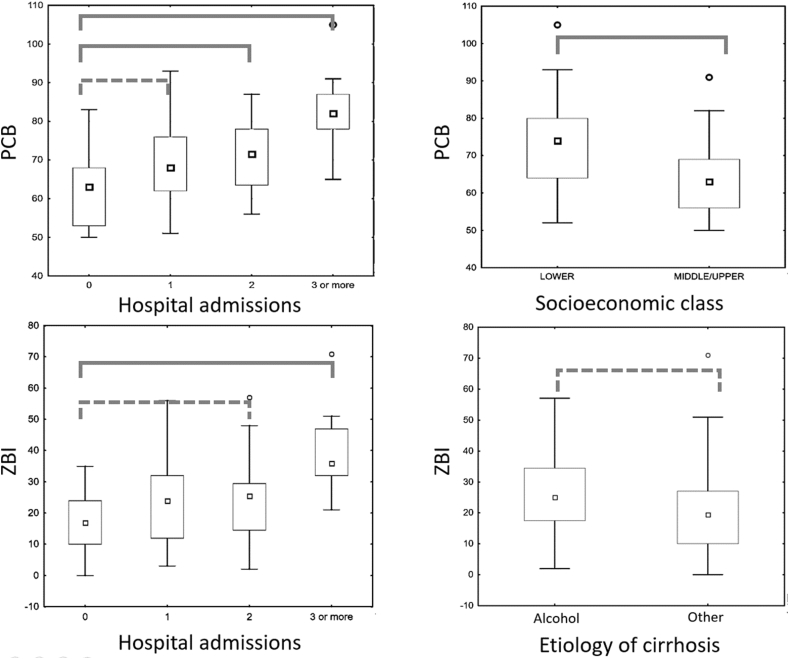

Factors Influencing Caregiver Burden Scores

Upon univariate analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with increased caregiver burden: lower patient education, high Child-Pugh and MELD scores, alcohol as etiology of cirrhosis, presence of minimal HE, previous episodes of HE, the number of previous hospital admissions, presence of ascites, lower family income, lower socioeconomic class, and lower caregiver education. On multivariable analysis, lower socioeconomic class and the number of hospital admissions were the only variables to significantly influence the PCB score. The ZBI score was significantly influenced by the number of hospital admissions and alcohol as etiology of cirrhosis (Figure-2).

Figure 2.

Impact of independent predictors of caregiver burden. Group comparison: Solid lines, statistically significant difference. Dotted lines, nonsignificant difference. PCB, Perceived Caregiver Burden; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

Factors Influencing Caregiver Depression and Anxiety Scores

Upon univariate analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with the BDI score: patient age and education, spouse as caregiver, caregiver gender and education, and presence of any comorbidity in the caregiver. However, none of these factors remained significant upon multivariable analysis.

For the BAI score, patient age, gender, education, past HE, and caregiver age, gender, and presence of any comorbidity were significant predictors on univariate analysis. However, none of these parameters significantly predicted the BAI score on multivariable analysis.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we elucidate the psychological burden faced by caregivers of patients suffering from liver cirrhosis and the factors influencing caregiver burden. Most of our patients were relatively young males (median age, 50 years; 70% males). Almost all patients belonged to the lower or middle socioeconomic class, and spouses were most often the primary caregivers. Presence of minimal HE or past episodes of overt HE predicted higher levels of caregiver burden and higher anxiety and depression scores. Ascites, higher Child class, and alcohol as etiology of cirrhosis too were associated with higher caregiver burden, but not higher anxiety or depression scores.

Patient factors such as severity of liver disease, alcohol as etiology, previous decompensations in the form of HE or ascites, and prior hospital admissions were associated with higher perceived burden. Patients from lower socioeconomic class and poor educational status of both patients and caregivers also led to higher burden. However, the most important factors influencing this perception were the number of prior hospital admissions, lower socioeconomic class, and alcohol as etiology of cirrhosis.

Chronic illnesses in family members cause considerable psychological burden on the caregivers. Therefore, it is our moral obligation as physicians to also care for the caregivers. It is important to understand which factors influence this perception of increased burden. Considering the median age of our patients was 50 years and most were males, the disease affected the primary earning members of the family. Moreover, most of our patients belonged to the lower socioeconomic strata, compounding the concern for financial stability. These patients are usually uninsured and have limited resources to achieve appropriate care. It is therefore not surprising that socioeconomic status is an independent predictor of caregiver burden.

Hospital admissions are a consequence and sometimes a cause of physiologically traumatizing event for the patients. However, they are also psychologically traumatizing events for the caregivers irrespective of the severity of the underlying disease of the patient. Repeated hospital admissions independently predicted increased caregiver burden in terms of both PCB and ZBI scores even when adjusted for the severity of liver disease and past decompensating events.

Ongoing alcohol abuse in patients with cirrhosis is a common cause of deterioration. It is also a common precipitating factor for acute decompensation of cirrhosis in our population.7,.22 Moreover, up to 35% of patients with cirrhosis on the transplant waiting list have ongoing alcohol use.23 We found that alcohol was also an independent factor increasing caregiver burden. Thus, aggressive counseling of patients as well as caregivers and appropriate deaddiction therapy to ensure complete alcohol abstinence are of paramount importance.

In a previous study on caregiver burden in patients with cirrhosis on liver transplant waitlist (all had medical insurance), Bajaj et al11 showed that patients with cirrhosis, especially those with past episodes of HE, perceived a high psychological burden. The psychometric performance and MELD score also correlated with caregiver burden. These findings are similar to our own inferences in this study. However, the psychometric scores and MELD independently predicted caregiver burden in the American population. In our study, hospital admissions and socioeconomic status were the strongest predictors of caregiver burden irrespective of severity of liver disease or cognitive function. As the majority of our study population was uninsured and had limited economic resources, it is understandable that financial concerns outweigh other stressors. Moreover, in the absence of transplant prospects due to economic constraints, repeated decompensating events leading to hospitalization could have led to a perception not unlike an incurable terminal disease.

An Italian study24 assessing caregiver burden in patients with varying degrees of HE showed that the objective caregiver burden increased as we move from the group with unimpaired cognition to that with minimal and then with overt encephalopathy. While we excluded those with overt encephalopathy, we did see a significant difference in burden between unimpaired cognition and minimal HE.

Another American study by Nguyen et al9 reported that caregivers of patients with cirrhosis had substantially low mental health scores than the standardized national norm. Similar to our experience, they also reported a history of HE, repeated hospital admissions, active alcoholism, and low household income as independent predictors of high caregiver burden. However, prospects of transplant and insurance details were not mentioned.

A Chinese study with partially state-insured care revealed economic concerns and presence of comorbidities in the caregiver predicted psychological burden.25 Caregiver comorbidity did not affect burden in our experience. This was probably because the most common comorbidity was hepatitis B, affecting nearly half of the patients, as opposed to hypertension in our population.

This was a cross-sectional study with outpatient subjects being a relatively stable group. We also excluded patients with recent acute decompensations and hepatocellular carcinoma, which accounted for a large subset of patients with cirrhosis. However, it was likely that the levels of perceived burden would be drastically higher. Furthermore, feelings of burden are not verbalized at times as providing care to a sick family member is an unquestioned duty in Indian culture. This factor might also have a role in underemphasizing the actual burden.

Although the physiological and psychological impact of cirrhosis on the patients have been studied in great detail, the humble informal caregiver remains an unrecognized, mostly ignored sufferer. In an economically constrained, predominantly uninsured population with little state-sponsored social support, the burden of the health of patients and well-being of the family may lead to depression, anxiety, and even caregiver burnout. It stands to reason that poor caregiver mental health is likely to affect the care of patient as well, and the same has been demonstrated in some studies on neurodegenerative diseases.26 It is important for physicians to address these concerns and keep a lookout for psychological deterioration of the caregiver as well. Even short sessions of counseling to address these concerns have resulted in improved patient outcomes.27 Thus, a multidimensional approach with regular counseling, support groups, and access to psychotherapy for caregivers in need should be incorporated as a part of comprehensive management of the patient.

In conclusion, the informal caregivers of patients with cirrhosis face a substantial psychological burden, which may adversely affect the caregiver and the patient. This is the first study on psychological burden of caregivers of patients with cirrhosis in the Indian setup. Repeated hospital admissions, alcoholism, and lower socioeconomic status are independent predictors of higher caregiver burden in our population. Acknowledgment and education of the caregiver may lead to better mental health of the caregivers and may even improve patient outcomes.

Author contributions

D.S. contributed to acquisition of data and manuscript drafting. S.R. contributed to data analysis and interpretation and manuscript drafting. R.K.D. and S.G. contributed to study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript. S.T., A.D., and Y.K.C. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Grant support

None.

Writing assistance

None.

References

- 1.Mokdad A.A., Lopez A.D., Shahraz S. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakoski M.O., McCammon R.J., Piette J.D. Burden of cirrhosis on older Americans and their families: analysis of the health and retirement study. Hepatology. 2012;55:184–191. doi: 10.1002/hep.24616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;5:138–147. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly M., Chick J., Gribble R. Predictors of relapse to harmful alcohol after orthotopic liver transplantation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:278–283. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Amico G., Garcia-Tsao G., Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A.S., Amarapurkar D.N. Natural history of cirrhosis of liver after first decompensation: a prospective study in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saraswat V., Singh S.P., Duseja A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in India: the Indian national association for study of the liver consortium experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1742–1749. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan A.B., Miller D. Who is taking care of the caregiver? J patient Exp. 2015;2:7–12. doi: 10.1177/237437431500200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen D.L., Chao D., Ma G., Morgan T. Quality of life and factors predictive of burden among primary caregivers of chronic liver disease patients. 2015;28:124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins M., Howard V.J., Wadley V.G. Caregiving strain and all-cause mortality: evidence from the REGARDS study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68:504–512. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj J.S., Wade J.B., Gibson D.P. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1646–1653. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki E.T., Santos R Dos, Miyazaki M.C. Patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation: caregiver burden and stress. Liver Transplant. 2010;16:1164–1168. doi: 10.1002/lt.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H.M., Shih F.J., Chang C.L., Lai I.H., Shih F.J., Hu R.H. Caring for overseas liver transplant recipients: taiwan primary family caregivers' experiences in mainland China. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3921–3923. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan M.Y., Amodio P., Cook N.A. Qualifying and quantifying minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:1217–1229. doi: 10.1007/s11011-015-9726-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhiman R.K., Saraswat V.A., Verma M., Naik S.R. Figure connection test: a universal test for assessment of mental state. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma R., Saini N.K. A critical appraisal of kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale in the present scenario. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2014;3:3–4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.130248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stommel M., Given C.W., Given B. Depression as an overriding variable explaining caregiver burdens. J Aging Health. 1990;2:81–102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarit S.H., Reever K.E., Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontol. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higginson I.J., Gao W., Jackson D., Murray J., Harding R. Short-form Zarit caregiver burden interviews were valid in advanced conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Ball R., Ranieri W.F. Comparison of beck depression inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. J Personal Assess. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajmany S., Nandi D.N. Adaptation of AT. Becket al.’s An inventory for measuring depression. Indian J Psychiatr. 1973;15:391. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhiman R.K., Agrawal S., Gupta T., Duseja A., Chawla Y. Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment is better than the asia-pacific association for the study of liver criteria for defining acute-on-chronic liver failure and predicting outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14934. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hempel J.-M., Greif-Higer G., Kaufmann T., Beutel M.E. Detection of alcohol consumption in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis during the evaluation process for liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2012;18:1310–1315. doi: 10.1002/lt.23468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montagnese S., Amato E., Schiff S., Facchini S. 2012. A Patients ’ and Caregivers ’ Perspective on Hepatic Encephalopathy; pp. 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei L., Li J., Cao Y., Xu J., Qin W., Lu H. Quality of life and care burden in primary caregivers of liver transplantation recipients in China. Medicine (Baltim) 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lwi S.J., Ford B.Q., Casey J.J., Miller B.L., Levenson R.W. Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2017;114:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701597114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajaj J.S., Ellwood M., Ainger T. Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy improves patient and caregiver-reported outcomes in cirrhosis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e108. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]