Abstract

Objective:

Augmentation with aripiprazole is an effective pharmacotherapy for treatment resistant late-life depression (TRLLD). However, aripirprazole can cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) such as akathisia and parkinsonism; these symptoms are distressing and can contribute to treatment discontinuation. We investigated the clinical trajectories and predictors of akathisia and parkinsonism in older patients receiving aripiprazole augmentation for TRLLD.

Methods:

Between 2009-2013, non-remitters to venlafaxine for the treatment of TRLLD were randomized to augmentation with aripiprazole or placebo in a 12-week trial. Participants were 60 years or older and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for major depressive episode with at least moderate symptoms. The presence of akathisia and parkisonism were measured at each visit using the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS) and Simpson Angus Scale (SAS) respectively. In an exploratory analysis, we examined a broad set of potential clinical predictors and correlates: age, sex, ethnicity, weight, medical co-morbidity, baseline anxiety severity, depression severity, concomitant medications including rescue medications, and aripiprazole dosage.

Results:

24/90 (26.7%) participants randomized to aripiprazole developed akathisia compared to 11/90 (12.2%) of those randomized to placebo. Greater depression severity was the main predictor of treatment emergent akathisia. Most participants who developed akathisia improved over time, especially with reductions in dosage. 15/91 (16.5%) of participants taking aripiprazole developed parkinsonism, but no clinical predictors or correlates were identified.

Conclusions:

Akathisia is a common side effect of aripiprazole, but it is typically mild and responds to dose reduction. Patients with greater baseline depression may warrant closer monitoring for akathisia. More research is needed to understand the course and predictors of treatment emergent EPS with antipsychotic augmentation TRLLD.

ClinicalTrials.gov Registration:

.

Keywords: geriatric depression, antidepressant, venlafaxine, aripiprazole augmentation, akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Aripiprazole augmentation is an evidence-based pharmacotherapeutic option for treatment-resistant depression with increasing evidence in late-life depression.1-3 Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) such as akathisia and parkinsonism are common adverse side effects from antipsychotic augmentation treatment of mood disorders.4,5 Both akathisia and parkinsonism may limit adequate dosing and lead to premature treatment discontinuation.6 Thus, it is important to understand the risk factors of developing these adverse effects. In general, there is a pauacity of data with regards to clinical predictors and trajectories of treatment emergent akathisia and parkinsonism with aripiprazole. There is even less data on on this topic when aripiprazole is used as an augmentation strategy in late life depresson (LLD).

Akathisia is characterized by a subjective feeling of restlessness and an objective movement component.7 In studies of adults treated with antipsychotics mainly for primary psychotic disorders, clinical correlates associated with akathisia include higher antipsychotic dosages, polypharmacy, depression, female gender, and older age. However, the clinical profiles have been inconsistent across studies,4,8-10 and studies investigating risk factors associated with antipsychotic-induced akathisia in late-life depression are limited.4

Parkinsonism is defined as the presence of coarse tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia.4 Risk factors have been clearly identified for the development of antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism in older adults receiving antipsychotics for the treatment of psychotic symptoms or agitation associated with dementia.4 They include older age, female gender, higher antipsychotic dosages, higher antipsychotic potency, and pre-existing EPS. Predictors of parkinsonism in depressed older adults receiving augmentation pharmacotherapy with an atypical antipsychotic, however, have not been described.

Given that parkinsonism may contribute to falls11, and akathisia may have a negative impact on treatment response9,12 and an association with treatment emergent suicidality,13 further investigation is necessary to elucidate the clinical correlates and course of these common and distressing adverse effects. Identifying patients at high risk of developing EPS may personalize care and minimize this potential negative effect on both tolerability and treatment outcomes.

We previously reported on the prevalence of EPS with aripiprazole augmentation in patients with LLD, finding that akathisia and parkinsonism were among the most common adverse effects in a randomized controlled trial.1 The present study is a comprehensive examination of these EPS syndromes, in order to provide clinicians with useful information regarding its course and predictors when used as augmentation strategy for incomplete response in LLD.

Methods

The data is from the Incomplete Response in Late-Life Depression: Getting to Remission (IRL-GRey) study; methods of this randomized controlled trial are described in detail elsewhere1. Participants were recruited in three academic medical centers (University of Pittsburgh; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health/University of Toronto; Washington University in St. Louis) between 2009 and 2013. Approval was obtained from the three institutional review boards and all participants provided written informed consent. Main eligibility criteria included age 60 years or older, diagnosis of a major depressive disorder, and a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)14 score ≥ 15 at recruitment. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number

Patients who did not achieve remission after approximately 12 weeks of open treatment with venlafaxine XR up to 300 mg per day continued it at the same dose and were randomized under double-blind conditions to the addition of either aripiprazole or placebo for 12 weeks. Remission was defined as a MADRS score of 10 or less at both of the final two study visits. Aripiprazole was started at 2 mg daily and titrated weekly based on clinical response and tolerability to a maximum of 15 mg/day. For management of treatment emergent EPS, there were no rescue medications as part of the study protocol; rather, a dose reduction strategy was employed. Participants were allowed lorazepam for anxiety or insomnia, or other non-benzodiazepine sedative medications such as zopiclone. In addition, trazodone up to 50mg was allowed fo insomnia. We tracked medications prescribed to the participants oustide of the study medications and report specifically on medications commonly used to manage EPS including beta-blockers, benzodiazepines and sedative/hypnotics.

The outcomes of interest for this analysis include the development of treatment-emergent akathisia or parkinsonism. Akathisia was assessed with the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS)7 and parkinsonism with the Simpson Angus Scale (SAS)15. For the SAS, item 7 related to “head dropping” was not assessed due to participant discomfort with the procedure.

Treatment-emergent akathisia was defined as a score of 2 (“mild akathisia”) or higher on the BAS global item (range 0–5)7. Treatment-emergent parkinsonism was defined liberally as an increase from baseline of the total SAS score by two points or more. Reliability was fair for both syndromes (intra-class correlation coefficient 0.57 for Simpson-Angus and 0.58 for Barnes Akathisia Scale). The calculated internal reliability of the BAS and SAS using the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.84 and 0.66, respectively in keeping with prevoius reports in other populations16.

We analyzed the following variables: age, sex, ethnicity, baseline depression severity as measured by MADRS, baseline anxiety as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)17, baseline EPS scores, weight, burden of co-morbid physical illness as measured by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale – Geriatrics (CIRS-G)18,19 where we report on the total score and number of categories endorsed, number of co-prescribed non-psychotropic medications, aripiprazole dosage, and treatment response as measured by a MADRS score of 10 or lower for two consecutive assessments. We also analyzed the use of common rescue medications such as beta-blockers, benzodiazepines and sedative/hypnotics prescribed outside of the study.

Among the participants randomized to aripiprazole (n = 91), we compared these variables between those with and without treatment-emergent EPS using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. We used logistic regression to identify potential correlates for each outcome. Initally, all variables were included followed by backward elimnation of the least significant predictors until only significant predictions remained in the model. The significance level was defined as 0.05 as this is primarily an exploratory analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using statistical software (R version 3.3.1).20

Finally, we performed a growth mixture model in the aripiprazole group to investigate the trajectories of developing akithisia. We used the global clinical assessment variable of the BAS at each time point. The model used a negative binomial model as the global scores assumed integer values from 0 to 4. Intercept, linear, and quadratic random slopes were specified since initial descriptive analysis showed that the trajectories were not well represented by a linear function. We selected the number of classes with Akaike information criterion21, Bayesian information criterion, and Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio tests.22,23 The analysis was conducted with statistical software (Mplus version 7.11).24

Results

In the IRL-GRey trial, 468 participants were recruited from July 20, 2009 to December 30, 2013. 181 (39%) did not achieve remission and were randomized to aripiprazole (n = 91) or placebo (n = 90). A greater proportion of participants achieved remission in the aripiprazole group compared to the placebo group (40 [44%] vs 26 [29%] participants; OR 2.0 [95% CI 1.1-3.7], p = 0.03). As reported, the most common adverse effects were akathisia and parkinsonism.

Akathisia

Of the 91 participants randomized to aripiprazole, one had missing akathisia scores; 24/90 (26.7%) developed akathisia compared to 11/90 (12.2%) of those randomized to placebo. In the aripiprazole group, 1/90 (1.1%) participant dropped out due to akathisia and 3/90 (3.3%) reported a temporary increase in suicidal thoughts due to akathisia. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants who developed akathisia versus those who did not. The only variable that differed significantly between those who developed akathisia and those who did not was baseline depression severity: participants who developed akathisia had higher depression severity with a mean (SD) MADRS score of 25.9 (6.1) vs 22.7 (6.4), Mann Whitney U Test, p = 0.03. Next, we conducted multivariate model including the identified variables4,10,25,26 that have been reported to be associated with the development of akathisia. Using logistic regression for predictive modelling where non significant variables were excluded with backward selection, only MADRS score remained significant (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.18). Of note, mean and maximum aripiprazole doses were not associated with the development of akathisia. We analyzed the effect of beta-blockers, benzodiazepines and sedative/hypnotics taken by participants before and after starting aripiprazole, and did not find any clinically meaningful associations with akathisia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants randomized to aripiprazole with and without treatment-emergent akathisia and parkinsonism

| No akathisia |

Akathisia | p-value* | No parkinsonism |

Parkinsonism | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 66 | 24 | 76 | 15 | ||

| Male, n(%) | 27(40.9) | 12(50.0) | 0.48 | 31(40.8) | 8(53.3) | 0.40 |

| Age, mean(SD) | 68.4(7.0) | 65.3(4.5) | 0.07 | 67.9(6.5) | 66.4(7.0) | 0.21 |

| White, n(%) | 60(90.9) | 20(83.3) | 0.45 | 66(86.8) | 14(93.3) | 0.68 |

| Remission, n(%) | 41(62.1) | 11(45.8) | 0.23 | 46(60.5) | 6(40) | 0.16 |

| CIRS-G total score, mean(SD) | 10.1(4.5) | 9.8(5.2) | 0.91 | 10.0(4.6) | 10.0(5.0) | 0.88 |

| CIRS-G count, mean (SD) | 6.2(2.4) | 5.8(2.7) | 0.55 | 6.2(2.4) | 5.8(2.9) | 0.51 |

| Number of prescribed nonpsychotropic medications, mean(SD) | 6.6(5.0) | 7.4(5.6) | 0.62 | 7.0(5.2) | 5.8(4.8) | 0.52 |

| BAS global item score at baseline mean(SD) | 0.38(0.7) | 0.38(0.49) | 0.53 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SAS at baseline, mean(SD) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.33(0.57) | 0.60(0.91) | 0.28 |

| MADRS at baseline mean(SD) | 22.7(6.4) | 25.9(6.1) | 0.03 | 23.1(6.4) | 25.7(6.4) | 0.24 |

| BSI at baseline, mean(SD) | 1.8(0.95) | 1.6(0.96) | 0.32 | 1.7(0.9) | 2.0(1.0) | 0.28 |

| Weight at baseline (lbs), mean(SD) | 183(43) | 193(50) | 0.49 | 186(45) | 188(41) | 0.62 |

| Highest aripiprazole dosage (mg/day), mean (SD) | 10.3 (3.8) | 10.29 (3.3) | 0.99 | 10.0(3.7) | 11.4(3.9) | 0.18 |

| Mean aripiprazole dosage (mg/day), mean (SD) | 7.6 (2.6) | 6.8 (2.8) | 0.25 | 7.1(2.6) | 8.3(3.0) | 0.12 |

Fisher test for categorical variables, Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables

SD: standard deviation, CIRS-G: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics, BAS : Barnes Akathisia Scale, SAS: Simpson Angus Scale, MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory

Akathisia Trajectories

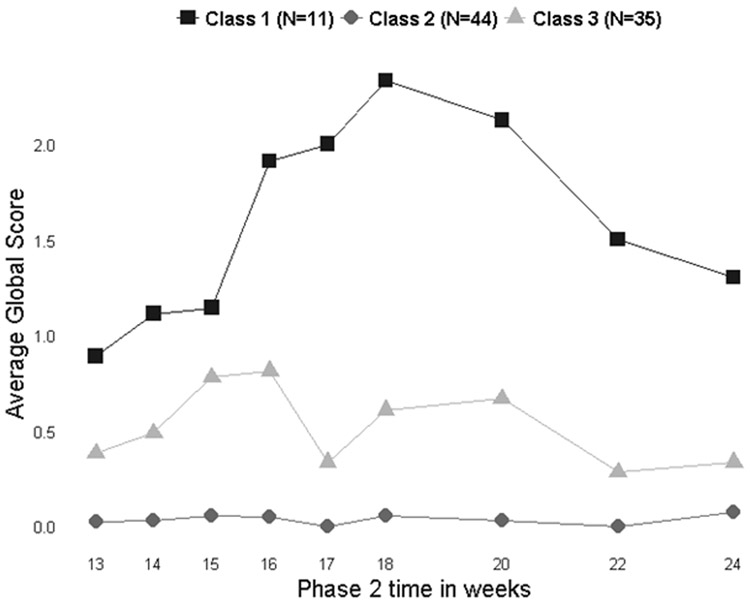

Clinical trajectories were modelled for akathisia only as there were insufficient data points to model parkinsonism (Figure 1). Based on fit indices from mixture models, a 3-class model showed a better fit as compared to 4 and 2 class models. In particular, the model did not improve significantly when going from 3 to 4 classes, and the 4-class model added a group with only 2 participants, which is too small for analysis. Class 1 (n=11) has participants with akathisia peaking and subsiding, defined by lower BAS global scores at the beginning and end of the study period, with peak scores associated with initial dosage titration. With time, akathisia seemed to resolve in this group. Class 2 (n=44) is the largest group and describes participants without akathisia having mostly BAS global scores of 0 throughout the study period. Class 3 (n=35) describes participants with time-varying akathisia and comprises participants who, in general, have some BAS global scores higher than zero occurring at various times during the study period but overall low global scores (mean BAS global score is below 1 at all time points). However, some participants in Class 3 met criteria for akathisia at certain study visits. We did not find any participant clinical characteristics associatd with the trajectories.

Figure 1:

Trajectory for the development of akathisia in participants randomized to aripiprazole

Parkinsonism

In the aripiprazole group, 15/91 (16.5%) developed parkinsonism compared to 2/90 (2.2%) in the placebo group, with 1/91 (1.1%) and 1/90 (1.1%) participants who dropped out due to worsening parkinsonism in these respective groups. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants who developed parkinsonism compared to those who did not. No statistically significant clinical predictors of the development of parkinsonism were identified in our bivariate comparison or multivariate logistic regression. There was no clinically meaningful association found with any rescue medication use.

Discussion

The IRL-GRey study showed that both akathisia and parkinsonism are relatively common adverse effects with aripiprazole augmentation in late-life depression. Consistent with previous literature, it was difficult to predict the development of treatment induced extrapyramidal symptoms. Our novel finding is that higher baseline depression severity was associated with a higher risk of akathisia. As this is an exploratory analsysis, further studies are needed to confirm this finding. We did not identify any characteristics associated with the development of parkinsonism.

These findings may help clinicians to identify some older depressed patients who are at higher risk of developing akathisia when treated with aripiprazole and to understand their clinical trajectory. Previous studies investigating the clinical correlates of antipsychotic-induced akathisia have focused on younger patients with psychotic disorders. A recent study27 of 372 patients (mean age: 32.9 years, SD 9.9) with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder investigated the clinical variables associated with antipsychotic-induced akathisia. They were unable to elucidate clear risk factors such as demographic characteristics such as age and sex. However, as in previous studies26,28, negative symptoms were significantly associated with an increased risk of akathisia. Similarly, in our sample of older adults with treatment-resistant depression, we could not identify demographic characteristics associated with akathisia, but more severe depression at baseline was identified as a risk factor. Thus, clinicians would be prudent to closely monitor depressed older patients with greater depression symptom severity for the development of akathisia when starting aripiparzole.

Finally, we identified three distinct akathisia trajectories: (1) akathisia peaking and subsiding; (2) no akathisia; (3) time-varying akathisia. The second and third trajectories correspond to more than 88% of patients (79/90) with no or low and transient akathisia, reflecting the overall good tolerability of aripiprazole augmentation in late-life depression. The first trajectory corresponds to akathisia likely associated with dose titration. As indicated by this trajectory, akathisia can be expected to improve with dosage reductions or the passing of time. It is congruent with several published reports of the occurrence of akathisia associated with increases in antipsychotic dosages followed by resolution of symptoms.8,10,25

A strength of our study was the rigor in which we measured extrapymaridal symptoms and our inclusion of inter-rater reliability, which has been rare among clinical trials in psychiatry.29 The analyses came from a prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial with frequent monitoring for akathisia and parkinsonism using validated scales. It is limited by the relatively small number of paticipants who developed EPS. In particular, there were few participants who developed parkinsonism, which may have limited our ability to identify its correlates. Given our sample of 90 participants and one significant association related to depression severity, there is 80% power to detect medium to large effect sizes, thus it is unlikely that there was a type 2 error. With regards to type 1 error, based on our number of predictors, a Bonferroni correction would yield a cut-off p-value for significance of 0.003. We did not use this cut off given that this is an exploratory analysis and would significantly impact the power of our investigation. Further study is warranted with larger sample sizes to elucidate clinical predictors of developing parkinsonism with aripiprazole augmentation. In addition, there may be an interaction with aripiprazole and venlafaxine as all participants were on 300 mg of the latter medication at randomization. This may impact the generlizability of the findings.

Nevertheless, our analysis addresses the limited data on EPS when aripiprazole is used as augmentation pharmacotherapy for late-life depression, an increasingly common treatment strategy in this population. In general, it is challenging for clinicians to predict which patients will develop extrapyramidal symptoms; we did not find any predictors for parkinsonism. The severity of depression may be an important risk factor when assessing and monitoring akathisia in these patients. The occurrence of suicidal ideation in association with akithisia is an important clinical phenomenon that clinicians must pay close attention to. Thus, clinicians may want to closely monitor patients with more severe depression using clinical measures such as the BAS. Fortunately, most older depressed patients who are prescribed aripiprazole will not develop akathisia, yet the emergence of these symptoms should be assessed carefully, particularly during initial dosage titration.

Clinical Points.

Akathisia and parkinsonism are common side effects with aripirazole augmentation in late life depression and are difficult to predict

Patients with more severe depressive symptoms may have a higher likelihood of developing akathisia, warranting close monitoring

In patients who develop treatment emergent akathisia, the clinical trajectories indicate that symtpoms are likely to resolve over time with dose reductions

Acknowledgments

Funding:

• Primary: National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH083660, P30 MH90333 and R34 to University of Pittsburgh, R01 MH083648 to Washington University, and R01 MH083643 and R34 MH101365 to University of Toronto)

• Additional: UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry, the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research and Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders (at Washington University), the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto

• Industry: Bristol-Myers Squibb contributed aripiprazole and placebo tablets, and Pfizer contributed venlafaxine extended release capsules for this study

• None of the funders were involved in the conduct of the study or in the writing of this manuscript

Footnotes

Previous presentation:

• Poster presented at the APA annual meeting, San Diego, California, May 20–24, 2017.

Declaration of Interests:

JHH reports no conflicts of interest.

BHM currently receives research funding from Brain Canada, the CAMH Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the US National Institute of Health (NIH). During the last five years, he also received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial), Eli-Lilly (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial), and Pfizer (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). He directly own stocks of General Electric (less than $5,000).

EJL reports research funding (current/past) from Janssen, Alkermes, Acadia, Takeda, Lundbeck,Barnes Jewish Foundation, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research.

MS reports no biomedical conflicts of interest.

JFK has received research support from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and medication supplies from Indivior and Pfizer for investigator initiated studies.

CFR has received research support from the NIH, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. BristolMeyerSquib and Pfizer have provided pharmaceutical supplies for his NIH sponsored research.

DMB has received research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), National Institute of Health (NIH), Brain Canada and the Temerty Family through the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Foundation and the Campbell Research Institute. He receives research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. and he is the site principal investigator for three sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He also receives in-kind equipment support from Magventure for an investigator-initiated study. He receives medication supplies for an investigator-initiated trial from Invidior. He has participated in advisory board for Janssen.

References

- 1.Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2404–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheffrin M, Driscoll H, Lenze E, et al. Pilot study of augmentation with aripiprazole for incomplete response in late-life depression: getting to remission. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2009;70(2):208–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffens DC, Nelson JC, Eudicone JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder in older patients: a pooled subpopulation analysis. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26(6):564–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caligiuri MR, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-Induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs & aging. 2000;17(5):363–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao K, Kemp DE, Fein E, et al. Number needed to treat to harm for discontinuation due to adverse events in the treatment of bipolar depression, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder with atypical antipsychotics. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haro JM, Novick D, Suarez D, Roca M. Antipsychotic treatment discontinuation in previously untreated patients with schizophrenia: 36-month results from the SOHO study. Journal of Psychiatric Research.43(3):265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154(5):672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller CH, Hummer M, Oberbauer H, Kurzthaler I, DeCol C, Fleischhacker WW. Risk factors for the development of neuroleptic induced akathisia. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;7(1):51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luthra V, Pinninti NR, Yoder K, Musthaq MS, Umapathy C, Levinson DF. Is akathisia associated with poor clinical response to antipsychotics during acute hospital treatment? General hospital psychiatry. 2000;22(4):276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachdev P, Kruk J. CLinical characteristics and predisposing factors in acute drug-induced akathisia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(12):963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams D, Watt H, Lees A. Predictors of falls and fractures in bradykinetic rigid syndromes: a retrospective study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2006;77(4):468–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levinson DF, Simpson GM, Singh H, et al. Fluphenazine dose, clinical response, and extrapyramidal symptoms during acute treatment. Archives of general psychiatry. 1990;47(8):761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen L A critical review of akathisia, and its possible association with suicidal behaviour. Human psychopharmacology. 2001;16(7):495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson J, Turnbull CD, Strickland R, Miller R, Graves K. The Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Scale: reliability and validity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1986;73(5):544–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson G, Angus J. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1970;45(S212):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janno S, Holi MM, Tuisku K, Wahlbeck K. Validity of Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS) in a naturalistic schizophrenia population. BMC neurology. 2005;5(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derogatis LR, Spencer P. Brief symptom inventory: BSI. Pearson Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA:; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linn BS, LINN MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16(5):622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry research. 1992;41(3):237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016; https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozdogan H Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):345–370. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuong QH. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 1989:307–333. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. 1998–2010 Mplus user’s guide. Muthén and Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braude WM, Barnes TR, Gore SM. Clinical characteristics of akathisia. A systematic investigation of acute psychiatric inpatient admissions. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1983;143:139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachdev P The epidemiology of drug-induced akathisia: II. Chronic, tardive, and withdrawal akathisias. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1995;21(3):451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berna F, Misdrahi D, Boyer L, et al. Akathisia: prevalence and risk factors in a community-dwelling sample of patients with schizophrenia. Results from the FACE-SZ dataset. Schizophrenia research. 2015;169(1–3):255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bratti IM, Kane JM, Marder SR. Chronic restlessness with antipsychotics. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulsant BH, Kastango KB, Rosen J, Stone RA, Mazumdar S, Pollock BG. Interrater reliability in clinical trials of depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1598–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]