Abstract

Background:

Ketamine is known to rapidly reduce depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (SI) in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), but evidence is limited for its acceptability and effectiveness in “real-world” settings. This case series examines serial ketamine infusions in reducing SI and depression scores in adults with MDD admitted to a tertiary care hospital.

Methods:

Five inpatients with MDD and SI admitted to hospital in Toronto, Canada received six infusions of 0.5 mg/kg intravenous (IV) ketamine (n = 5) over approximately 12 days, in addition to treatment-as-usual. Suicide and depression rating scores (Scale for Suicidal Ideation, SSI; Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, MADRS) were obtained at baseline, on treatment days, on days 14 and 42 (primary endpoint).

Results:

All patients experienced benefit with ketamine. SSI scores diminished by 84% from 14.0 ± 4.5 at baseline to 2.2 ± 2.5 at study endpoint. MADRS scores diminished by 47% from 42.2 ± 5.3 at baseline to 22.4 ± 8.0. Two patients withdrew from the study, one to initiate electroconvulsive therapy and one due to an adverse event (dissociative effects) during the ketamine infusion.

Limitations:

The major limitation of this study is the small sample size.

Discussion:

These preliminary pilot data are promising with a greater than two-fold reduction in SI following ketamine infusions. They demonstrate that six serial ketamine infusions may be safe and feasible. These findings support the need for large scale randomized controlled trials to confirm the efficacy of serial ketamine for treatment of SI in “real-world” settings.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, Suicide, Ketamine, Midazolam, Inpatients

1. Introduction

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that intravenous ketamine infusions can provide rapid relief of depressive symptoms in people suffering from treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) as well as bipolar depression with various studies showing rapid response to a single infusion which persists for at least 72 hours (Aan Het Rot et al., 2012; DiazGranados et al., 2010; George et al., 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2011; Mathew et al., 2012; Murrough et al., 2013a; Singh et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017; Zarate et al., 2006, 2012). A recent consensus statement by the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments states that ketamine infusion treatment may be considered for certain patients with MDD depending on severity, treatment-resistance and urgency (Sanacora et al., 2017). Similar conclusions have been drawn in the United Kingdom (Singh et al., 2017). Collectively, the literature indicates that ketamine infusions may be one of the most effective and rapid treatments for depression available, although optimism about these results must be tempered by the fact that the duration of response in single infusion studies with ketamine is often short-lived. Emerging evidence suggests that treatment response may be extended with repeated infusions (Singh et al., 2016; Murrough et al., 2013b). An open-label study of up to six ketamine infusions over 12 days and a follow-up period lasting up to 83 days thereafter found a 71% response rate in subjects with treatment resistant depression with median time to relapse being 18 days (Murrough et al., 2013b). A double-blind study of twice and three-times weekly ketamine infusions for up to four weeks with the possibility of two additional weeks of open-label treatment and a further three weeks of ketamine-free follow-up found that ketamine was superior to placebo in reducing depression scores at day 15 (Singh et al., 2016). In this second study, gains in the ketamine group appeared to persist throughout the double-blind phase and continued, albeit with partial regression of depression scores, through the open-label and ketamine-free phases of the trial (Singh et al., 2016). While these results show some promise, they also indicate that even repeated administration of ketamine infusions may not sustain initial gains.

Single ketamine infusions have also been shown to rapidly and dramatically reduce suicidal ideation (SI) in depressed patients (Bartoli et al., 2017; DiazGranados et al., 2010; Grunebaum et al., 2017; Ionescu et al., 2016; Murrough et al., 2015; Price et al., 2009; Vulser et al., 2018) with some evidence suggesting that this effect may be partially distinct from ketamine's impact on depressive symptoms (Ballard et al., 2014; Wilkinson et al., 2017). While this result is promising, there has been some concern that the rapid relief of depression or SI may be followed by a relapse of symptoms (Singh et al., 2017) with at least one case report describing the culmination of such a scenario in a suicide attempt (Grunebaum et al., 2017; López-Díaz et al., 2017; Vande Voort et al., 2016).

While most studies of ketamine have used single doses, had short follow-up periods, and focused on treatment-resistant MDD samples, ketamine has also been proposed as an adjunct to expedite response to standard antidepressant drugs in patients who are severely depressed but not necessarily treatment-resistant (Hu et al., 2016).

It follows that the most likely practical use of ketamine is as an adjunct to standard antidepressant treatment to rapidly relieve SI in depressed patients when time is of the essence such as during an acute care hospitalization. However, despite the growing body of literature described above, there are few published reports of its use under “real-world” conditions, for example, a busy, tertiary care hospital. One feasibility study did examine serial ketamine infusions for depressed patients with suicidal ideation (Vande Voort et al., 2016), however the treatment was open-label and single-arm (i.e. did not include a placebo comparator group). The data presented here emerge from a planned single-site, randomized, double-blind, midazolam-controlled pilot trial which had to be terminated early due to unexpected costs associated with regulatory changes and increased monitoring requirements in Canada. The study involves six serial ketamine infusions over approximately two weeks in reducing SI in subjects with MDD who were admitted to hospital for a major depressive episode. The original hypothesis of this study was that ketamine would be superior to midazolam in producing improvement in suicide and depression scores at two endpoints (14 and 42 days). While sample size constraints prevent useful between-group comparisons and limit generalizability of findings, case series data in subjects receiving the ketamine intervention can nevertheless be informative and may provide preliminary data to guide the design of future randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The pilot data presented here begin to address the research gap on the effectiveness of serial ketamine infusions together with standard care for inpatients in a real-world setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

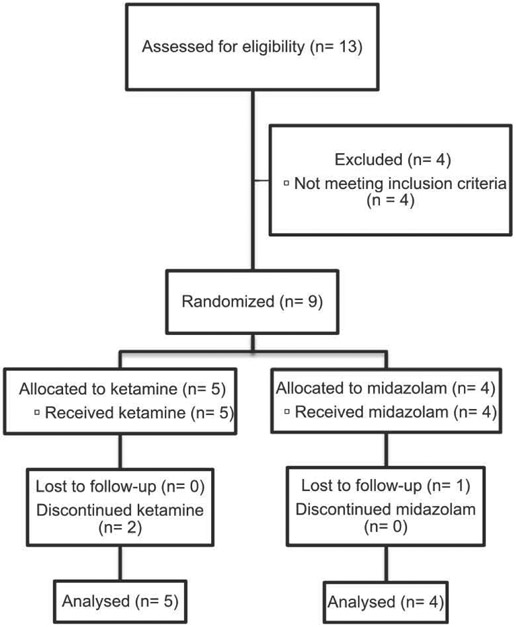

A single-site, double-blind, pilot RCT was planned to compare approximately 12 days of serial infusions of ketamine vs. midazolam (placebo) as an adjunct to treatment as usual with 13 adult inpatients with MDD and SI per group. However, the study terminated early due to unexpected costs associated with regulatory changes in Canada. The final sample included 9 patients with 5 randomized to ketamine and 4 randomized to midazolam.

The study was conducted at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, a large university-affiliated academic hospital in Toronto, Canada (see Fig. 1 for details of recruitment). Inclusion criteria were intentionally broad to mimic what would likely be used in a tertiary care clinical setting. These included: 1) age 18–65 years; 2) inpatient status at entry; 3) diagnosis of MDD and current major depressive episode confirmed by the MINI Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998); 4) SI at baseline as defined by a score of > 0 on either of the Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI, clinician administered; Beck et al., 1979) and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS) or both; 5) able to provide informed consent. MDD did not have to be treatment-resistant (defined as ≥ 2 failed lifetime antidepressant trials of adequate dose and duration). There was no minimum required depression score for entry although depression had to be severe enough to prompt admission to hospital. Comorbid psychiatric conditions were identified via the MINI and review of clinical notes and were confirmed by clinical assessment of the trial investigator (MS).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram indicating the number of patients screened, randomized, intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis.

Exclusion criteria included: 1) current or past manic symptoms; 2) current or past psychotic symptoms; 3) current substance or alcohol dependence or substance abuse within the past month; 4) pervasive developmental disorder or dementia; 5) unstable medical illness (as was judged by the trial investigator in consultation with the anesthesia team, and based on results of a physical examination, vital signs, routine bloodwork and electrocardiogram; 6) medical condition that would contraindicate the use of ketamine/midazolam or affect their metabolism; 7) current treatment with ketamine; 8) any treatment that might contraindicate the use of study medications (e.g., concomitant monoamine oxidase inhibitors); 9) concomitant electroconvulsive therapy; and 10) pregnancy.

In keeping with the notion of studying ketamine as an adjunct to standard/”real-world” inpatient care, study infusions were given as an add-on to treatment as usual (TAU), with subject medications initiated or changed at clinicians’ discretion. There were few restrictions on what TAU could entail except for concurrent ketamine or ECT. Subjects were only required to be inpatients during the first infusion. Subjects could be discharged and return to receive subsequent infusions at the discretion of their inpatient psychiatrist.

Participants were randomized in 1:1 fashion to receive either 0.5 mg/kg of ketamine or 0.045 mg/kg of midazolam, consistent with previous ketamine RCTs (Murrough et al., 2013a), in 100 ml normal saline infused over 40 minutes. Ketamine or midazolam was delivered on six separate occasions over approximately 12 days. Infusions could be slowed to 50 minutes at the discretion of the anaesthesia care provider, if subjects were experiencing side effects. Infusions were administered three times weekly on available treatment days until subjects had received six infusions. Vital signs including heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, ECG and arterial oxygen saturation were monitored throughout infusions and for at least one hour post-infusion. Anesthesiologists were present for the infusions of the earliest enrolled subjects and an anesthesia assistant (a professional who is trained to administer anesthetic drugs under the direct supervision of a physician anesthesiologist) was present to monitor all infusions thereafter. An anesthesiologist was immediately available to provide support, if necessary. Following the initial infusions, in-person anesthetist support was never requested and phone support was only sought in a single instance.

2.2. Visits and measures

Study visits occurred at baseline, on each infusion day (visits 1–6), on days 14 (i.e. 1–3 days after the end of acute treatment) and 42 (i.e. one month after the end of acute treatment). Subjects were assessed at baseline and at subsequent visits by the study investigator and a research coordinator both of whom were blinded to treatment allocation. Assessment of the primary hypothesis that ketamine would be superior to midazolam in reducing SI at days 14 and 42 was done via change in SSI and the CSSRS from baseline. The Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI) (Beck et al., 1979) is a 19-item scale that has been the historical gold standard for measuring suicidal ideation. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS) is the new gold standard for evaluating suicide risk in RCTs and involves a comprehensive set of questions designed for both baseline and subsequent visits (Posner et al., 2011). The SSI was used as it provides a continuous measure of suicidal ideation, plans and intent while the CSSRS was used to capture additional categorical information including recent suicide attempts and self-harm.

Secondary measures included the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; 17-items), Clinical Global Impression of Severity/Improvement scales (CGI-S, CGI-I), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR), and presence of adverse effect as reported by subjects or on inpatient clinical record. The MADRS is a clinician administered depression questionnaire composed of 10 items and uses a 6-point rating scale. It is the standard scale used in recent RCTs for depression (Montgomery et al., 1979). Changes from baseline to endpoint on MADRS item 10 which examines suicidal thoughts were reportedly separately in addition to total MADRS scores. The HRSD is a widely used clinician administered measure for assessing depression severity as it considers both physical and psychological aspects of depression (Hamilton, 1960). The 17-item HRSD is commonly used in RCTs to assess treatment efficacy/effectiveness. The CGI-S and CGI-I are designed to briefly assess and track severity of illness and response to treatment (Busner et al., 2007). The SDS is a complementary scale to the CGI that measures functional impairment rather than severity or improvement (Sheehan, 1983). The QIDS-SR is a 16-item patient self-report scale modeled after diagnostic symptom criteria for MDD (Trivedi et al., 2004).

The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (ID# 361–2013), written informed consent was obtained, and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02593643).

Because of the small sample size, outcome data are presented descriptively for both subjects receiving ketamine and midazolam. Study results use a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach for those in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as any subject who received at least one infusion/had one post-baseline measure. The Mann-Whitney U Test and χ2 tests were used for baseline between-group comparisons of continuous and categorical variables respectively using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) due to non-normally distributed data.

3. Results

3.1. Ketamine case series

Baseline demographics, measures and comorbidities are shown in Table 1. Two male and three female subjects aged 36.8 ± 7.5 yrs all of whom had treatment resistent depression received serial ketamine infusions. All subjects experienced a reduction in SSI and MADRS scores with ketamine (Fig. 2). SSI scores for the group diminished by 84% from 14.0 ± 4.5 at baseline to 2.2 ± 2.5 at study endpoint. MADRS scores in the ketamine group diminished by 47% from 42.2 ± 5.3 at baseline to 22.4 ± 8.0. Mean score on MADRS item 10 (suicidal ideation) diminished by 68% from 3.8 ± 0.45 at baseline to 1.2 ± 0.84 at study endpoint. Mean total MADRS scores after infusions 1–6 were 24.4 ± 14.4, 21.2 ± 12.7, 21.4 ± 13.8, 23.6 ± 12.4, 22.4 ± 13.1, and 22.4 ± 13.3 respectively. Two subjects withdrew from the study, one to initiate electroconvulsive therapy and one due to an adverse event (dissociative effects) during the infusion. Two of three completers correctly guessed that they had received ketamine at study endpoint.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics, measures, comorbid mental disorders and history of suicidal behaviour/self-harm for the nine study subjects.

| Total sample (n = 9) | Ketamine (n = 5) | Midazolam (n = 4) | Statistic | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.78 ± 7.48 | 36.80 ± 7.46 | 27.75 ± 3.77 | U = 2.00 | 0.048* |

| Female | 5 (56%) | 3 (60%) | 2 (50%) | χ2 = 0.09 | 0.800 |

| MADRS | 37.22 ± 8.90 | 42.20 ± 5.26 | 31.00 ± 9.02 | U = 2.00 | 0.05 |

| HAM-D | 28.67 ± 4.36 | 30.40 ± 3.78 | 26.50 ± 4.51 | U = 5.50 | 0.266 |

| Treatment resistant depression† | 7 (78%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (50%) | χ2 = 3.21 | 0.07 |

| SSI | 16.56 ± 7.26 | 14.00 ± 4.47 | 19.75 ± 9.46 | U = 5.50 | 0.268 |

| CGI-S | 5.44 ± 0.53 | 5.40 ± 0.55 | 5.50 ± 0.58 | U = 9.00 | 0.777 |

| QIDS-SR | 26.56 ± 4.95 | 25.00 ± 4.47 | 28.50 ± 5.45 | U = 5.00 | 0.221 |

| SDS | 26.78 ± 2.68 | 28.40 ± 1.67 | 24.75 ± 2.36 | U = 2.00 | 0.044* |

| SDS days lost past week | 5.67 ± 1.94 | 6.40 ± 0.89 | 4.75 ± 2.63 | U = 7.00 | 0.421 |

| SDS days unproductive past week | 6.44 ± 1.67 | 7.00 ± 0.00 | 5.75 ± 2.50 | U = 7.50 | 0.264 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Anxiety disorders GAD | 5 (56%) | 3 (60%) | 2 (50%) | ||

| Social phobia | 4 (44%) | 2 (40%) | 2 (50%) | ||

| Panic disorder | 1 (11%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | ||

| Agoraphobia | 1 (11%) | 0 | 1 (25%) | ||

| OCD | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | ||

| PTSD | 3 (33%) | 2 (40%) | 1 (25%) | ||

| Substance abuse (Past) | 2 (22%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (25%) | ||

| BPD | 2 (22%) | 0 | 2 (50%) | ||

| Self-harm without suicidal intent** | 6 (67%) | 3 (60%) | 3 (75%) | ||

| Suicide attempt** | 7 (78%) | 3 (60%) | 4 (100%) |

p < 0.05; Values indicate mean ± SD or count (%).

prior to study enrollment.

Defined as ≥ 2 failed antidepressant trials of adequate dose and duration.

MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; HAM-D, The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SSI, Scale of Suicidal Ideation; CGI-S, The Clinical Global Impression – Severity scale; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report.; MDD, major depressive disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; χ2, Chi-Squared; U, Mann-Whitney U Test.

Fig. 2.

Scale of suicidal ideation (A) and Montgomery–Åsberg depression rating scale (B) Scores at baseline, after the first infusion, at day 14 and 42 in subjects receiving ketamine (K1-5).

In terms of conventional antidepressant drug treatment, two subjects were started on a new antidepressant during their admission/concurrent with the trial. One subject had an antidepressant dose increase. One subject continued previously prescribed antidepressants while one subject was on no medication throughout. One subject received lurasidone, one subject received lisdexamfetamine and one subject received temazepam. Of the three subjects who received all six infusions, two were hospitalized throughout and received standard treatment while one was discharged prior to receiving all infusions and returned as an outpatient to complete them.

All subjects reported at least one non-serious adverse event. These included dissociation, headache and dry skin/mouth/lips (each reported by two subjects) and diarrhea, constipation, chest pain, dizziness on standing, emotional detachment, drowsiness, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, pain/numbness at site of IV/saline lock, metallic taste, general pain and a feeling of being “high” or intoxicated (each reported by one subject). Two subjects experienced hypertension (systolic BP > 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP > 100 mmHg) during and after some infusions.

3.2. Midazolam case series

Baseline demographics, measures and comorbidities for four subjects receiving midazolam, two of whom were treatment-resistant, are also shown in Table 1 and SSI/MADRS scores in Fig. 3. SSI scores for the group diminished by 37% from 19.8 ± 9.5 to 12.5 ± 15.0 at study endpoint. MADRS scores diminished by 34% from 31.0 ± 9.0 to 20.5 ± 15.7. Mean score on MADRS 10 (suicidal ideation) diminished by 29% from 3.5 ± 1.7 at baseline to 2.5 ± 3.0 at study endpoint. Mean total MADRS scores after infusions 1–6 were 22.0 ± 15.9, 12.5 ± 10.0, 11.5 ± 8.3, 17.5 ± 13.1, 18.3 ± 8.8, and 15.5 ± 13.6 respectively. There were no dropouts in the midazolam group. Three of the four completers correctly guessed that they had received midazolam at study endpoint.

Fig. 3.

Scale of suicidal ideation (A) and Montgomery–Åsberg depression rating scale (B) Scores at baseline, after the first infusion, at day 14 and 42 in subjects receiving midazolam (M1-4).

There was one serious adverse event, a non-fatal suicide attempt, which occurred in a subject receiving midazolam. One subject was started on a new antidepressant during their admission/concurrent with the trial. One subject had an antidepressant dose increase. Two subjects continued previously prescribed antidepressants. One subject received liothyronine and one subject received lorazepam. Three of four subjects reported at least one non-serious adverse event including nausea/vomiting, headache and dizziness on standing (each reported by two subjects) and chest pain, dissociation, fatigue, drowsiness, sound sensitivity, strange (vivid and unpleasant) dreams, visual disturbances, shaking and worsening of an eating disorder (each reported by one subject).

4. Discussion

This case series presents data indicating that six serial ketamine infusions may be safe and feasible and, thus, may be an acceptable adjunct to standard antidepressant therapies under “real-world” conditions for rapid relief of SI in patients admitted to hospital with MDD. This study begins to address an important gap in the research literature which has, as yet, focused on efficacy rather than pragmatic designs. Although the small sample size limits firm conclusions, it is evident that, while subjects in both the ketamine and midazolam groups experienced a rapid reduction in SI, the reduction in the ketamine group appeared to be somewhat larger, more robust, and longer-lasting (up to 42 days) with SSI scores increasing in the midazolam group after the second infusion. While the sample size is a limitation, the endpoint measure at 42 days is an important strength of the study as most previous research has focused on much shorter timescales. These findings support a growing literature indicating that ketamine infusions can be an effective treatment for SI (Ballard et al., 2014; Bartoli et al., 2017; DiazGranados et al., 2010; Grunebaum et al., 2017; Ionescu et al., 2016; Murrough et al., 2015; Price et al., 2009; Wilkinson et al., 2017). The greater improvement in SI scores compared to depression scores is compatible with the hypothesis that ketamine may have anti-suicidal effects above and beyond the effect on depression (Wilkinson et al., 2017). Furthermore, although the trial did not require subjects to have treatment-resistant depression, all ketamine subjects and seven of nine total subjects had demonstrated treatment resistance. This has two important implications. First, it is notable that ketamine appeared to outperform midazolam in spite of the fact that it was delivered to a more treatment-resistant sample. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it suggests that most subjects eligible and willing to receive ketamine in a real world, tertiary care setting may have treatment-resistance, a finding that supports the generalizability of the existing literature focusing exclusively on this population.

Given the relative novelty of ketamine for treatment for suicidality and the complex ethical issues surrounding an emerging treatment (Singh et al., 2017), the question of how to position ketamine as a treatment in MDD and SI remains open to debate. Most previous studies of ketamine infusions for mental disorders have focused on treatment-resistant depression (Aan Het Rot et al., 2012; DiazGranados et al., 2010; George et al., 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2011; Mathew et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017; Zarate et al., 2006, 2012; Murrough et al., 2013b). One could argue that this is inherently problematic since ketamine response is often short-lived and may not address the need for a long-term effective treatment in this population. In contrast, given that suicidal crises are often fleeting (Daigle et al., 2005), typically subside after response to standard antidepressants, and the fact that antidepressant response usually occurs after several weeks (Undurraga et al., 2012), a treatment that rapidly alleviates SI during the waiting period for standard treatment to take effect is clinically meaningful. The fact that ketamine infusion appears to be effective for reducing SI is especially important given the dearth of effective biological treatments that specifically targets suicidal ideation and behaviors (Mann et al., 2005a, 2005b; Zalsman et al., 2016). Although the sample size is too low to draw conclusions about suicidal behavior, it is noteworthy that the one suicide attempt observed occurred in the midazolam control group. Larger studies are needed to corroborate this finding. Nevertheless, one possible model for viewing the relationship between ketamine and standard antidepressants is akin to that of an analgesic given for acute fracture pain and a cast used to promote longer term healing. Even if ketamine is not a panacea, this study contributes to evidence suggesting that it may have a place in acute care. It is hard to overstate the potential impact of giving severely ill, suicidal patients hope that relief may be available in the moment.

This study has several limitations. The most important limitation is the small sample size which resulted from the study's premature terminations due to budgetary constraints that were incompatible with increased regulatory monitoring requirements in Canada. Chance variations may have magnified or obscured ketamine's anti-suicidal impact. Assuming that the change and standard deviation in SSI scores observed here was maintained in a larger study, a sample of 30 subjects in each group would be needed to detect a difference between ketamine and midazolam infusions at day 42 assuming α = 0.05 and β = 0.80. Allowing subjects to have multiple comorbid disorders in addition to MDD as well as treatment as usual, was pragmatic/generalizable to many inpatient units, however these factors also introduce the potential for confounding. Furthermore, psychotropic medications were not controlled for. While ketamine itself is a relatively inexpensive medication, the higher level of care required for infusions increases its costs substantially. Thus, expenses associated with repeated ketamine infusions are an important factor and need to be addressed as a part of the feasibility and cost benefit assessment for large scale use. Future studies will need to establish the optimal number of infusions to assess the efficacy of ketamine for extended depressive symptom relief by comparing the number of ketamine infusions within the same study. The use of midazolam as an active-placebo comparator, the current standard in the literature (Murrough et al., 2013a; Murrough et al., 2013b; Murrough et al., 2015; Grunebaum et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2017), was important because its central nervous system effects, including sedation and amnestic effects, make it more difficult for subjects to guess whether they are receiving ketamine treatment. Nevertheless, 5 out of 7 participants correctly guessed group assignment in the current study. Whether this reflected unblinding based on side-effect profile versus an inference based on improvement in mood symptoms is unclear. Given this study's focus on the ketamine case series, the choice of adequate control is less relevant here but remains an important, unresolved issue for the field. Finally, while this study examined changes in suicide and depression scores, it did not explore underlying mechanisms of improvement or improvement in specific domains of depression such as cognitive dysfunction which has been identified as an understudied aspect of MDD (Gonda et al., 2015). Future studies of ketamine could include neuropsychological measures of executive function which plays a role in regulation of emotion.

In conclusion, this case series provides initial support for the notion that serial ketamine may be an acceptable and effective treatment for rapid relief of SI in inpatients with MDD under “real-world” conditions. The early termination of this study limited the sample size and thus the ability to arrive at definitive conclusions. Nevertheless, our findings support the need for large, adequately-powered RCTs to determine both the efficacy and safety of serial ketamine infusions as an adjunct to usual treatment in real world settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elihu Henry, Robert Chong, and Teresa Przybyszewski for administering ketamine and midazolam and monitoring patients. We are grateful to the support from John Iazzetta and Katrina Hatzifilalithis for assisting with study oversight and randomization as well as Ms. Catherine Reis and Mr. Yas Nishikawa for providing study monitoring.

Funding/Support

This work was funded by the Dr. Brenda Smith Bipolar Fund (Toronto, Canada). The funder had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures

Dr. Zarate is listed as a coinventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression and suicidal ideation. Dr. Zarate is listed as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, (S)-dehydronorketamine and other stereoisomeric dehydro and hydroxylated metabolites of (R,S)-ketamine metabolites in the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain. Dr. Zarate is listed as co-inventor on a patent application for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine in the treatment of depression, anxiety, anhedonia, suicidal ideation and post-traumatic stress disorders. Dr. Zarate has assigned his patent rights to the U.S. government but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government. The other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre research ethics board (ID# 361–2013).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.073.

References

- Aan Het Rot M, Zarate CA Jr, Charney DS, Mathew SJ, 2012. Ketamine for depression: where do we go from here? Biol. Psychiatry 72, 537–547. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard ED, Ionescu DF, Vande Voort JL, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, Luckenbaugh DA, Brutsché NE, Ameli R, Furey ML, Zarate CA Jr, 2014. Improvement in suicidal ideation after ketamine infusion: relationship to reductions in depression and anxiety. J Psychiatr. Res 58, 161–166. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli F, Riboldi I, Crocamo C, Di Brita C, Clerici M, Carrà G, 2017. Ketamine as a rapid-acting agent for suicidal ideation: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 77, 232–236. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A, 1979. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 47 (2), 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle MS, 2005. Suicide prevention through means restriction: assessing the risk of substitution. A critical review and synthesis. Accid. Anal. Prev 37, 625–632. 10.1016/j.aap.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busner J, Targum SD, 2007. The clinical global impressions scale. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 4, 28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiazGranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Henter ID, Luckenbaugh DA, Machado-Vieira R, Zarate CA Jr, 2010. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 1605–1611. 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Yang H, Sun Y, Zhang J, Li G, Zheng Y, Liu Y, 2017. Ketamine rapidly relieves acute suicidal ideation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Oncotarget 8, 2356–2360. 10.18632/oncotarget. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George D, Gálve V, Martin D, Kumar D, Leyden J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Harper S, Brodaty H, Glue P, Taylor R, Mitchell PB, Loo CK, 2017. Pilot randomized controlled trial of titrated subcutaneous ketamine in older patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry S 1064-7481, 30351–30352. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda X, Pompili M, Serafini G, Carvalho AF, Rihmer Z, Dome P, 2015. The role of cognitive dysfunction in the symptoms and remission from depression. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 14, 27 10.1186/s12991-015-0068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Keilp JG, Moitra VK, Cooper TB, Marver JE, Burke AK, Milak MS, Sublette ME, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, 2017. Ketamine versus midazolam in bipolar depression with suicidal thoughts: A pilot midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 19, 176–183. 10.1111/bdi.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, 1960. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23, 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YD, Xiang YT, Fang JX, Zu S, Sha S, Shi H, Ungvari GS, Correll CU, Chiu HF, Xue Y, Tian TF, Wu AS, Ma X, Wang G, 2016. Single I.V. ketamine augmentation of newly initiated escitalopram for major depression: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled 4-week study. Psychol. Med 46, 623–635. 10.1017/S0033291715002159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim L, DiazGranados N, Luckenbaugh DA, Machado-Vieira R, Baumann J, Mallinger AG, Zarate CA Jr, 2011. Rapid decrease in depressive symptoms with an N-methyl-d-asparate antagonist in ECT-resistant major depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 35, 1155–1159. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu DF, Swee MB, Pavone KJ, Taylor N, Akeju O, Baer L, Nyer M, Cassano P, Mischoulon D, Alpert JE, Brown EN, Nock MK, Fava M, Cusin C, 2016. Rapid and sustained reductions in current suicidal ideation following repeated doses of intravenous ketamine: secondary analysis of an open-label study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, e719–e725. 10.4088/JCP.15m10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Díaz Á, Fernández-González JL, Luján-Jiménez JE, Galiano-Rus S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, 2017. Use of repeated intravenous ketamine therapy in treatment-resistant bipolar depression with suicidal behaviour: a case report from Spain. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol 7, 137–140. 10.1177/2045125316675578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, 2005a. The medical management of depression. N. Engl. J. Med 353, 1819–1834. Retrieved from,. http://www.nejm.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H, 2005b. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 294, 2064–2074. Retrieved from,. http://www.jamanetwork.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Shah A, Lapidus K, Clark C, Jarun N, Ostermeyer B, Murrough JW, 2012. Ketamine for treatment-resistant unipolar depression: current evidence. CNS Drugs 26, 189–204. 10.2165/11599770-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Åsberg M, 1979. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 134, 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, Iqbal S, Pillemer S, Foulkes A, Shah A, Charney DS, Mathew SJ, 2013a. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 1134–1142. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Perez AM, Pillemer S, Stern J, Parides MK, aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Mathew SJ, Charney DS, Iosifescu DV, 2013b. Rapid and longer-term antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine infusions in treatment-resistant major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 250–256. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Soleimani L, DeWilde KE, Collins KA, Lapidus KA, Iacoviello BM, Lener M, Kautz M, Kim J, Stern JB, Price RB, Perez AM, Brallier JW, Rodriguez GJ, Goodman WK, Iosifescu DV, Charney DS, 2015. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med 45, 3571–3580. 10.1017/S0033291715001506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin G, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ, 2011. The Columbia- suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS): initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multi-site studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Nock MK, Charney DS, Mathew SJ, 2009. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 522–526. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, Mathew SJ, Turner MS, Schatzberg AF, Summergrad P, Nemeroff CB, 2017. American Psychiatric Association (APA) council of research task force on novel biomarkers and treatments. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 399–405. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC, 1998. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59, 22–33. Retrieved from,. http://www.psychiatrist.com. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, 1983. The Sheehan Disability Scales In the Anxiety Disease and How to Overcome it. Charles Scribner and Sons, New York, pp. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, De Boer P, Cooper K, Lim P, Pinter C, Murrough JW, Sanacora G, Shelton RC, Kurian B, Winokur A, Fava M, Manji H, Drevets WC, Van Nueten L, 2016. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 816–826. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I, Morgan C, Curran V, Nutt D, Schlag A, McShane R, 2017. Ketamine treatment for depression: opportunities for clinical innovation and ethical foresight. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 419–426. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TP, Chen MH, Li CT, Lin WC, Hong CJ, Gueorguieva R, Tu PC, Bai YM, Cheng CM, Krystal JH, 2017. Dose-related effects of adjunctive ketamine in Taiwanese patients with treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2482–2492. 10.1038/npp.2017.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Crismon ML, Shores-Wilson K, Toprac MG, Dennehy EB, Witte B, Kashner TM, 2004. The inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR), and the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (QIDS-C) and self-report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol. Med. 34, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ, 2012. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 851–864. 10.1038/npp.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Voort JL, Morgan RJ, Kung S, Rasmussen KG, Rico J, Palmer BA, Schak KM, Tye SJ, Ritter MJ, Frye MA, Bobo WV, 2016. Continuation phase intravenous ketamine in adults with treatment-resistant depression. J. Affect. Disord 206, 300–304. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulser H, Vulser C, Rieutord M, Passeron A, Lefebvre D, Baup E, Seigneurie AS, Thauvin I, Limosin F, Lemogne C, 2018. Ketamine use for suicidal ideation in the general hospital: case report and short review. J. Psychiatr. Pract 24 (1), 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, Feder A, Sos P, Wang G, Zarate CA Jr, Sanacora G, 2017. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, Carli V, Höschl C, Barzilay R, Balazs J, Purebl G, Kahn JP, Sáiz PA, Lipsicas CB, Bobes J, Cozman D, Hegerl U, Zohar J, 2016. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 646–659. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA Jr, Brutsche NE, Ibrahim L, Franco-Chaves J, DiazGranados N, Cravchik A, Selter J, Marquardt CA, Liberty V, Luckenbaugh DA, 2012. Replication of ketamine's antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: a randomized controlled add-on trial. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 939–946. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK, 2006. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-d-asparate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 856–864. Retrieved from,. http://www.jamanetwork.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.