Abstract

Background

This study determined if there are observable patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics significantly associated with whether a tooth demonstrating an external crack also has an internal crack.

Methods

Two hundred and nine dentists in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network enrolled 2,858 adults with a vital posterior permanent tooth having at least one observed external crack. Presence and characteristics of internal cracks were recorded for 435 cracked teeth that were treated. Generalized estimating equations were used to identify significant (p<0.05) independent odds ratios (OR) associated with the tooth having internal cracks.

Results

Overall, 389 (89%) teeth had at least one internal crack, with 46% of these having two or more. Sixty-nine percent of treated cracked teeth were associated with one or more types of pain assessed prior to treatment; 53% associated with cold, 37% with biting and 26% with spontaneous pain. In the final model, biting pain, having an external crack that connected with a restoration, or an external crack that extends onto the root were each associated with over a 2-fold increased odds of having an internal crack.

Conclusions

Essentially 9 of 10 teeth that had at least one external crack also had at least one internal crack.

Practical implications

The external cracks that a dental practitioner should be most concerned about, as they are most likely to be associated with internal cracks in the tooth, are those in which the patient experiences biting pain, is connected with a restoration of some type, or extends onto the root.

Keywords: cracked teeth, practice-based research, internal crack, Cracked tooth, Symptoms

Introduction

The observation of teeth with cracks is an everyday occurrence for dental practitioners, but the most appropriate treatment for those teeth, and the optimal timing of that treatment, is often uncertain. Although there is extensive literature on the treatment of teeth with cracks, it has been pointed out that there is no widely accepted definition, diagnostics or evaluative criteria for the word “crack” in many published studies, making interpretation of treatments and their effects difficult (1). Treatment strategy is also complicated by the difficulty the practitioner has with reliably estimating the severity of the crack or crack system, especially the extent of penetration into the tooth. This may distinguish a crack from a craze, which is a surface crack present in enamel only, and a fracture, in which two parts are separated (1).

Internal cracks, i.e. cracks within the dentin that are unobservable from the external surface, are significant as they may be associated with a higher risk of symptoms development and invasive dental treatment, possibly with poorer outcomes. Unfortunately there are currently no clinically available diagnostic tools for determining the depth of cracks into dentin, or the presence of dentin cracks that eventually involve the enamel. High magnification (14–18X) provides profound visualization of enamel cracks (2), but is still deficient for detecting cracks in dentin in an intact tooth. Therefore, clarifying the association between observable characteristics of the patient, tooth, or crack system and the presence of internal tooth cracks would be very useful for practitioners to help guide treatment decisions. Recently micro-CT of extracted teeth was used to show a moderate but significant association between the length of a crack on the occlusal surface and the proximal length of the crack, including the root surface (3).

Determining associations between measurable characteristics and dental outcomes or conditions in an observational study requires a large sample size to provide adequate statistical power. The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (4) provides the ideal research context for such a study. This work represents one of several studies investigating the association between the characteristics of teeth with cracks and a variety of conditions, such as tooth symptoms and crack progression (5, 6).

Our objective was to determine if there are observable characteristics at the patient-, tooth- and external crack-level that are significantly associated with whether a posterior permanent tooth with at least one observable external crack also has an internal crack. The presence of an internal crack was visually verified during preparation of the tooth for restorative treatment.

Methods

The detailed description of the process for enrolling patients and collecting data has been published (5). Overall, 209 participants in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network enrolled a convenience sample of 2,858 adult subjects who had a vital posterior tooth with at least one observed external crack. For this study, an external crack was defined as “an obvious break of the external contiguous structure of the tooth, but involves no loss of tooth structure (e.g. lost cusp).” Teeth could be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Target patient enrollment per dentist was as many as possible up to 20 within eight weeks. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the lead investigators (TH & JF) and those of the network’s six regions approved the study. Consent was obtained for all participating subjects.

Patient-, tooth-, and crack-level data were collected by dentist and practice personnel who were trained in data collection. Data forms are publicly available at [http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results/cracked-tooth-registry.php]. Cold, typically a refrigerant or ice, was used to confirm tooth vitality (7), although these or other methods used were at the discretion of the practitioner.

Of the 2,858 cracked teeth examined at baseline, 486 had a surgical treatment [extraction, endodontic, or restorative] completed at the same visit. As will be reported in a future paper, teeth were most likely to be recommended for treatment when there was any evidence of pain, caries was present, or when a crack could be observed on a radiograph (in only 5% of the teeth). Of the 486 teeth examined, dentists indicated that they could assess whether or not internal cracks were present on 437. Analyses are presented on 435 surgically treated cracked teeth for whom dentists indicated they were able to assess whether internal crack(s) were present (data was missing for two). The following characteristics of each identified internal crack were recorded: stained, connected with pre-existing restoration, surface involved, cusps involved, connected with another crack, continuation of an external crack, crack included enamel, and crack included dentin.

The 435 cracked teeth were treated by 152 practitioners (range 1 to 12 patients/practitioner, median of 2, with an Inter Quartile Range (IQR) of 1–4), between April 8, 2014 and April 30, 2015. There were 22 to 31 practitioners from across each of the six regions of the network and the mean number of patients/practitioner did not vary by region [p=0.3], ranging from 2.00 (South Atlantic) to 3.27 (Western).

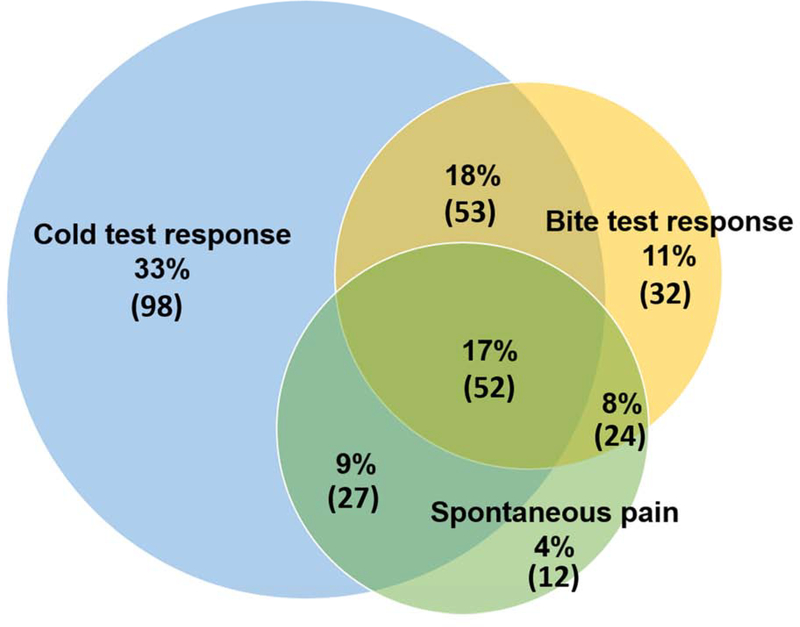

As previously described (5), teeth were classified as symptomatic if they had pain to cold (N=230/435, 53%), biting (N=163/435, 37%) or were spontaneously painful (N=113/435, 26%). Of the 435 teeth, 69% had one or more types of pain (298/435), and of the 298 that were painful, 142 (48%) had only one type of pain, 104 (35%) had two and 52 (17%) had all three types of pain (Figure 1). To distinguish a painful response from a “normal” response by a vital tooth, dentists were asked to test and compare a “normal” tooth, e.g., a contralateral tooth.

Figure 1:

Distribution according to source of symptoms among 298 symptomatic teeth.

Data Analysis

Frequencies were obtained overall and according to whether or not a cracked tooth had an internal crack, by patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics, and whether or not the cracked tooth was symptomatic, overall and by type of symptoms. Initial analyses with patient demographics and behaviors were used to inform categorization for the regression model. In a univariable fashion, each patient-, tooth-, and crack-level characteristic was entered into a logistic regression model that used a generalized estimating equations (GEE) method which adjusted for clustering of patients within the practice (PROC GENMOD in SAS with CORR=EXCH option). All characteristics with p<0.05 after adjusting only for clustering of patients within the practice were entered into a full model and backwards elimination, again using GEE to adjust for clustering, was performed, to identify independent associations with the presence of internal cracks. This was repeated after restricting to treated cracked teeth with one external crack and one internal crack to identify characteristics associated with the internal crack being a continuation of the external crack. All characteristics with p < 0.05 were retained and included in a reduced, final model. All p-values presented are adjusted for clustering of patients within practices. All interaction terms were tested for significance at the 0.05 level after the final model was fit.

Results

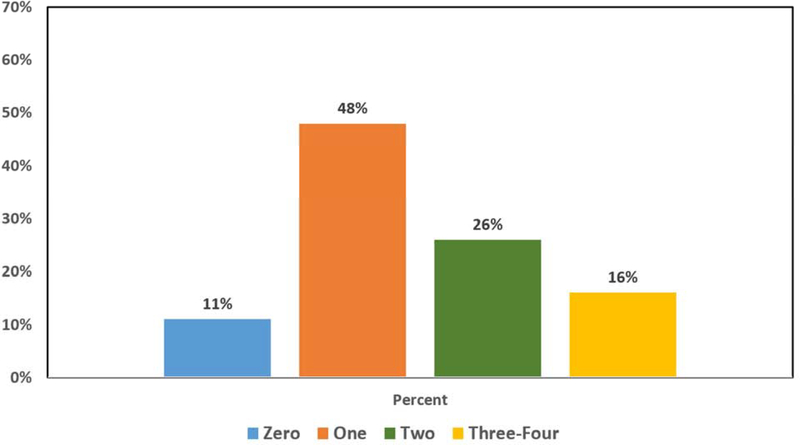

Of the 435 treated cracked teeth that could be assessed for internal cracks, 389 (89%) had at least one internal crack. Of these 389 teeth, 209 (54%) had just one internal crack, 111 (28%) had two, 35 (9%) had three and 34 (9%) had four or more internal cracks (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Distribution of 435 treated teeth according to number of internal cracks.

Patient-level characteristics (Table 1 - supplemental)

The mean and median age of the participants was 53 (SD= 12) years; with an IQR of 44 to 62 (range 21 to 85) years. Age did not differ for those with and without internal cracks. A preponderance of patients (85% for each) were of non-Hispanic white race-ethnicity and had some form of dental insurance. About two-thirds of the patients (61%) were female, and 67% said that they clenched, ground, or pressed on their teeth at some time (5). As stated above, 69% of treated cracked teeth were associated with one or more types of pain; 53% with cold, 37% with biting and 26% with spontaneous pain.

After adjusting for clustering within practice, treated cracked teeth in female patients (OR=1.9) were more likely to have internal cracks than those in males (Table 1). Patients treated in the South Atlantic region were less likely to have an internal crack than those treated in other regions (OR=0.3). Treated cracked teeth associated with some type of pain were more likely to have an internal crack than those without pain (OR=2.0), and this was primarily due to those teeth for which biting pain was recorded (OR=2.6).

Table 1.

Associations (odds ratios) of patient-, tooth-, and external crack-level characteristics with presence of one or more internal cracks within 435 treated1 cracked teeth.

| Adjusted cluster-only2 | Full model3 | Final (reduced) model4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | p-value | Odds Ratio | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | ||

| Biting pain | 2.6 | .002 | 2.4 | .004 | 2.6 | 1.4–4.8 | .002 | ||

| Female | 1.9 | .048 | 1.9 | .071 | X | X | x | ||

| South Atlantic region | 0.3 | .037 | 0.4 | .058 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.8 | .04 | ||

| Caries present on tooth | 0.5 | .042 | 0.5 | .064 | X | X | x | ||

| External crack connects with restoration | 2.2 | .037 | 2.1 | .047 | 2.1 | 1.2–4.0 | .04 | ||

| External crack extends to root | 3.6 | .007 | 3.4 | .021 | 3.1 | 0.9–10.5 | .02 | ||

| External crack involves occlusal surface | 2.3 | .021 | 2.7 | .17 | x | x | x | ||

| External crack involves >1 surface | 2.2 | .028 | 0.9 | .8 | x | x | x | ||

Restored and/or endodontically treated allowing the ability to assess presence of internal cracks

All characteristics that were associated with cracked tooth having an internal crack at p<0.05 after adjustment for clustering within practitioner using GEE are listed.

Full model: All characteristics that were associated with cracked tooth being symptomatic at p<0.05 after adjustment for clustering within practitioner using GEE were included in the model.

Reduced model: Using GEE, starting with the full model, backwards elimination was used, removing one characteristics at a time, starting with highest p-value, retaining only characteristics with p < 0.05.

x: not significant, p>0.05, not retained in reduced

Tooth-level characteristics (Table 2 - supplemental)

Nearly all of the cracked teeth were in occlusion with an opposing tooth (98%), and a preponderance had a natural or restored opposing tooth (89%) and were molars (85%). The majority of the teeth (66%) had multiple external cracks and were mandibular teeth (54%). It was less frequent for cracks to be on teeth with caries (36%) or on teeth with a wear facet through enamel (26%). Even fewer cracks were on teeth having exposed roots (16%), having a non-carious cervical lesion (NCCL) (7%) or having evidence of a crack on a radiograph (5%). The only tooth-level characteristic among treated cracked teeth showing a significant association with the presence of internal cracks was if the tooth had caries; these treated cracked teeth were less likely to have internal cracks (OR=0.5) (Table 1).

Crack-level characteristics (Table 3 – supplemental)

A preponderance of the treated cracked teeth had an external crack that was in a vertical direction (94%), was stained (83%), connected with a restoration (75%), was detectable by an explorer (73%), or blocked trans-illuminated light (68%). Each of the five tooth surfaces was approximately equally represented with a crack; ranging from 41% for the facial surface to 55% for the distal surface. Fewer of the treated cracked teeth had an external crack that was in a horizontal direction (36%), more than one direction (17%), extended to the root (9%), was in an oblique direction (7%) or connected with another crack (6%). The only crack-level characteristics among treated cracked teeth associated with the presence of an internal crack were whether or not a crack connected with a restoration (OR=2.2) or involved the occlusal surface (OR=2.3), or involved more than one surface (OR=2.2) (Table 1).

Independent associations

There were no significant interactions among the independent variables, indicating that an additive model was appropriate. The independent associations with whether or not there was an internal crack are presented in Table 1. In the final model, biting pain (OR=2.6; 95% CI: 1.4–4.8), having an external crack that connected with a restoration (OR=2.2; 95% CI: 1.2–4.0), or an external crack extending to the root (OR=3.1; 95% CI: 0.9–10.5) were each associated with over two-fold increased odds of having an internal crack. In the South Atlantic region, a treated tooth with an external crack was less likely to have an internal crack (OR=0.3; 95% CI: 0.2–0.8). Although patients in the South Atlantic region had similar proportions of teeth recommended for treatment as compared with the other regions, among those so recommended, fewer had the treatment completed at baseline (32% vs. 49%, p=0.01), and this could be due to fewer having any dental insurance (65 vs. 80%, p<0.001) and fewer presenting with biting pain (10% vs. 17%, p=0.004).

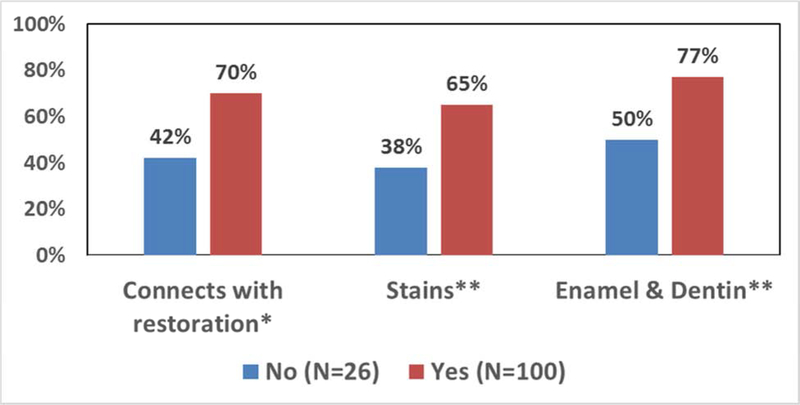

Of particular interest was to identify the characteristics of external cracks that were directly connected with an internal crack verified by invasive treatment. These cracks would potentially be considered to be the most serious, as they would be the most extensive in terms of penetration into the tooth. It was possible to correlate which internal cracks connected with a specific external crack only in those teeth that had one external crack and also had only one internal crack (n=126), in which the internal crack was specifically identified as being a continuation of an external crack (n=100; Table 2). Three characteristics were independently associated with an external crack continuing to an internal crack, one external characteristic (connects with a restoration) and two internal characteristics (being stained and involving dentin and enamel) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of external cracks that are directly continued as an internal crack for teeth with only one internal crack.

| Continuation of external crack | |||||

| No (N=26) | Yes (N=100) | Adjusted | |||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | P |

| Has an external crack that … | |||||

| Is detectable with explorer | 11 | 42% | 67 | 67% | 0.02 |

| Connects with a restoration | 11 | 42% | 70 | 70% | 0.02** |

| Mesial | 6 | 23% | 45 | 45% | 0.04 |

| Occlusal | 8 | 31% | 57 | 57% | 0.047 |

| Has internal crack that … | |||||

| Is stained | 10 | 38% | 65 | 65% | 0.01** |

| Involves enamel | 18 | 69% | 96 | 96% | 0.01 |

| Involves enamel & dentin | 13 | 50% | 77 | 77% | 0.02** |

| Involves dentin only | 8 | 31% | 4 | 4% | 0.01 |

| Independent | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Has an external crack that … | |||||

| Connects with a restoration | 2.4 | 1.0–5.0 | 0.047 | ||

| Has internal crack that … | |||||

| Is stained | 2.7 | 1.2–6.0 | 0.028 | ||

| Involves enamel & dentin | 3.4 | 1.3–8.7 | 0.039 | ||

independently associated in the final model

Figure 3.

Independently associated external crack characteristics for 126 teeth with 1 external crack and 1 internal crack that was a continuation of the external crack (N=100)

Discussion

Perhaps the most striking result from this study was the fact that almost nine out of ten treated teeth having at least one visible external crack also had at least one internal crack; these internal cracks are only discoverable upon preparation of the tooth for treatment. It is important to be cognizant that the teeth were typically being treated because of the presence of caries or pain symptoms, especially to biting. Perhaps even more unexpected is the fact that nearly half of these teeth had more than one internal crack. In retrospect, perhaps this should not have been surprising because these cracks are not typically discernible in an intact tooth (8), and the extent of the “pathology” of the tooth, such as internal cracks, only becomes perceptible when the tooth is opened up or “deconstructed” (9). Based on these results from over 150 geographically distributed U.S. dentists examining 435 teeth with external cracks that were invasively treated, it seems logical to assume that a tooth that has a visible external crack and is being recommended for treatment will almost always have at least one deep crack (i.e. extending into the dentin).

Treatment of teeth with cracks is controversial due to the many different options and paucity of definitive clinical outcome data (10). Survival of root canal treated cracked teeth is less than ideal, i.e. 15% failure in 2 years (11), so more conservative approaches are appealing. Bonded composite with or without cuspal coverage has been tried to preserve tooth structure and pulp vitality with good success at 7 years for 40 restorations, although ultimately 7.7% of the non-cuspal coverage restorations eventually required root canal therapy (12). In the current study, of the 2,858 cracked teeth enrolled, only approximately 1% (29 teeth) were initially recommended for endodontic treatment by the over 200 dentists involved. This number represents only about 3% of those teeth initially recommended for treatment, predominantly restorative, at the baseline visit (n=1,018).

It has been stated that the management of a tooth with a crack should be based on the biological, not the mechanical problem, in that the crack itself is not the disease and only provides a means for bacterial entry and possible pulpitis or periodontitis, which are the true diseases (1). In a study in which 100 teeth were treated according to this conservative philosophy, only 15 were recommended for initial endodontic treatment due to pulp exposure, crack into the pulp or the need for a post. Of the 85 teeth treated by removal of all restorations and any cracks, and placing sedative fillings to confirm tooth health prior to placing crowns, only 4 proceeded to require root canal therapy within 5 years. Thus, when the diagnosis of reversible pulpitis due to cracks could be confirmed, about 80% of teeth could be saved without the need for endodontic treatment (1). Although the authors were specific in stating that all cracks were removed in the 85 teeth that were not initially treated with endodontics, they did not characterize or comment on the presence of internal cracks. To our knowledge, no study has provided such data until this present work.

Overall, 69% of the teeth recommended for treatment had at least one type of pain. This percentage was higher than the 45% of the 2,858 teeth overall enrolled in this study that had at least one pain symptom (5). This suggests that a tooth with a visible external crack and presenting with some symptoms is more likely to be recommended for treatment. This is consistent with the observation that an early diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome has been associated with more successful restorative management and a better prognosis (13).

In a previous study, we showed that the predominant pain symptom for patients with a tooth with at least one external crack was cold sensitivity (6). In the current study, there was a strong association between pain and the presence of an internal crack, mainly due to biting pain, not to cold or spontaneous pain. This is consistent with other reports showing that pain on biting is the most common type of pain for teeth with visible external cracks (1, 14). In fact, patients with pain on biting had more than two and a half fold greater odds of having an internal crack than those without biting pain. Thus, when a patient has a tooth that responds with pain on biting and has at least one visible external crack, particularly one that is on the occlusal surface and connects with a restoration, it is very likely to have at least one internal crack. This is a significant finding because it is expected that this combination of characteristics would more likely lead a practitioner to recommend treatment. Further, pain on biting is considered the most-accurate diagnostic tool for a cracked tooth, at least for cracks visible to the practitioner (15). Because in the present study nearly every tooth with a visible crack that was recommended for treatment also had at least one internal crack, pain on biting may be a good indicator of the existence of an internal crack, likely because an internal crack is present within dentin. In this case, the movement of fluids into and out of the crack during the application of pressure on the tooth would be the stimulus for pain (16). However, it is important to point out these characteristics do not necessarily associate with the internal crack being a continuation of the external crack (Table 2). The only external crack characteristics in the final model associated with the internal crack connecting with the external crack was the crack connecting to a restoration.

A result that has no immediate explanation is the fact that patients in the South Atlantic region were less likely to have teeth with internal cracks (OR=0.3). The association remained at the level of significance (p=0.03) in the final reduced model.

At the crack-level, cracks connecting with a restoration and those extending to the root surface were associated with increased odds for an internal crack. It would seem logical that restorations may serve as stress concentrators and potentially wedges that impose tensile stresses within the tooth during biting and clenching. These stresses could cause cracks to propagate into the dentin and form internal cracks, though in this study there was no association between clenching behavior and the presence of an internal crack. One would also expect that external cracks that are more-extensive in nature, such as those extending to the root surface, would be more likely to be associated with internal cracks (3).

The strengths of this study are its large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Another strength is the fact that it was conducted in dental practices under routine dental practice conditions, and that it allowed for the assessment of both external and internal cracks in the same population of teeth, something that has never before been described in such an extensive manner. The limitations of the study are that the overall number of patients treated to allow internal crack observation represented only a subset of the total pool (n=435), that the number of external cracks that could be verified as continuing directly to an internal cracks was an even smaller subset (n=100), and that the overall crack number may be underestimated due to some cracks being non-observable.

This study provides a practical guide in suggesting that the external cracks that a dental practitioner should be most concerned about, as they are most likely to be associated with internal cracks not observable during an examination of the intact tooth, are those in which the patient experiences biting pain, is connected with a restoration of some type, and extends onto the root of the tooth. Furthermore, an externally observable crack that connects with a restoration is more likely to be continued directly as an internal crack, and this is more likely to involve both the enamel and dentin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant U19-DE-22516. The authors are grateful to the network’s regional coordinators who worked with network practitioners to conduct the study. Midwest region: Sarah Verville Basile, RDH, MPH, Christopher Enstad, BS; Western region: Camille Baltuck, RDH, BS, Lisa Waiwaiole, MS, Natalia Tommasi, MA, LPC; Northeast region: Patricia Ragusa, BA; South Atlantic region: Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP, Brenda Thacker, AS, RDH, CCRP; South Central region: Claudia Carcelén, MPH, Shermetria Massengale, MPH, CHES, Ellen Sowell, BA; Southwest region: Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, Colleen Stewart, MA. The authors are also grateful to the 12 network practitioners who participated in this study as pilot study practitioners. Midwest: David Louis, DDS, Timothy Langguth, DDS; Western: William Reed Lytle, DDS, Don Marshall, DDS; South Atlantic: Stanley Asensio, DMD, Solomon Brotman, DDS; South Central Region: Jocelyn McClelland, DMD, James L. Sanderson Jr, DMD; Southwest: Robbie Henwood, DDS, PhD, Michael Bates, DDS; Northeast: Julie Ann Barna, DMD, MAGD; Sidney Chonowski, DMD, FAGD.

A Web site devoted to details about The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jack L. Ferracane, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, 2730 S.W. Moody Ave., Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Ellen Funkhouser, School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 2nd Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007.

Thomas J. Hilton, Operative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, 2730 S.W. Moody Ave., Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Valeria V. Gordan, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, University of Florida, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Cynthia L. Graves, Private Practice of General Dentistry, 10418 Lake Creek Parkway, Austin, TX, 78750.

Karyn A. Giese, Private Practice of General Dentistry, 1580 Elmwood Ave., Rochester, NY 14620.

William Shea, Private Practice of General Dentistry, 708 Dallas St., Chetek, WI.

Daniel Pihlstrom, Evidence-Based Care & Oral Health Research, Permanente Dental Associates, 500 NE Multnomah St., 100, Portland, OR 97232-2009.

Gregg H. Gilbert, Department of Clinical and Community Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 Second Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007.

References

- 1.Abbott P, Leow N. Predictable management of cracked teeth with reversible pulpitis. Aust Dent J 2009; 54(4):306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark DJ, Sheets CG, Paquette JM. Definitive diagnosis of early enamel and dentin cracks based on microscopic evaluation. J Esthet Restor Dent 2003; 15(7):391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Fu K, Qiao F, Zhang X, Fan Y, Wang L, Li P, Wu Z, Wu L. Predicting extension of cracks to the root from the dimensions in the crown: A preliminary in vitro study. JADA 2017; 148(10):737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, Fellows JL, Gordan VV, Makhija SK, Meyerowitz C, Oates TW, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Foy PJ, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent 2013; 41(11):1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gilbert GH, Baltuck C, Benjamin P, Louis D, Mungia R, Meyerowitz C; National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Correlation between symptoms and external characteristics of cracked teeth: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA 2017; 148(4):246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gordan VV, Huff KD, Barna J, Mungia R, Marker T, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Associations of types of pain with crack-level, tooth-level and patient-level characteristics in posterior teeth with visible cracks: Findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent 2018; 70:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pigg M, Nixdorf D, Nguyen R, Law A, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Validity of preoperative clinical findings to identify dental pulp status: a National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Study. J Endod 2016; 42(6):935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubisich EB, Hilton TJ, Ferracane J; Northwest Precedent. Cracked teeth: a review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent 2010; 22(3):158–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheets CG, Wu JC, Rashad S, Phelan M, Earthman JC. In vivo study of the effectiveness of quantitative percussion diagnostics as an indicator of the level of the structural pathology of teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2016; 116(2):191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerji S, Mehta SB, Millar BJ. Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 2: restorative options for the management of cracked tooth syndrome. Br Dent J 2010; 208(11):503–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan L, Chen NN, Poon CY, Wong HB. Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. Int Endod J 2006; 39(11):886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opdam NJ, Roeters JJ, Loomans BA, Bronkhorst EM. Seven-year clinical evaluation of painful cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration. J Endod 2008; 34(7):808–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agar J R, Weller R N. Occlusal adjustments for initial treatment and prevention of cracked tooth syndrome. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 60(2):145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron CE. The cracked tooth syndrome: additional findings. JADA 1976; 93(5):971–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo DG, Yi YA, Shin SJ, Park JW. Analysis of factors associated with cracked teeth. J Endod 2012; 38(3):288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brannstrom M The hydrodynamic theory of dentinal pain: sensation in preparations, caries, and the dentinal crack syndrome. J Endod 1986; 12(10):453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.