Abstract

Parapharyngeal infections carry a significant risk of extensive suppuration and airway compromise. We report the case of a patient presenting with a right paranasopharyngeal abscess, featuring atypical symptoms that made diagnosis particularly challenging. Complications included evidence of right vocal cord paralysis, likely secondary to involvement of the vagus nerve. Notably, this paralysis occurred in isolation, without involvement of cranial nerves IX or XI, which would be expected from jugular foramen encroachment. Imaging demonstrated the presence of a collection extending towards the skull base, which was drained using a transnasal endoscopic approach, avoiding the use of external incisions. Tissue biopsies from the abscess wall suggest that the underlying aetiology was minor salivary gland sialadenitis, which has not been previously reported in the literature.

Keywords: Parapharyngeal abscess, Sialadenitis, Vocal cord palsy, Surgical endoscopy

Background

Parapharyngeal abscess formation is uncommon in the antibiotic era. Nevertheless, it remains important to recognise and treat any abscess promptly. Because of their location, they have the potential to cause airway compromise, spread into the retropharyngeal space, carotid space and mediastinum.1 Prompt surgical drainage, classically using either a transoral or external incision, is indicated.2

A patient presented with a parapharyngeal abscess of unusual aetiology, previously undocumented in the literature. Typical clinical features were absent on presentation, making diagnosis particularly challenging. Ultimately, the collection was drained using a non-traditional transnasal endoscopic approach.

Case history

An 18-year-old woman who was otherwise fit and well, presented to the emergency department with a five-day history of generalised malaise, associated with pyrexia, coryzal symptoms, sore throat, cough, headache, neck pain, photophobia and nausea. She also reported right-sided otalgia. She had previously suffered from recurrent episodes of tonsillitis, for which she had undergone a tonsillectomy.

On initial examination, the patient was febrile. She was noted to have right-sided level II and III cervical lymphadenopathy, with a normal oropharynx and ear. Testing for nuchal rigidity demonstrated a positive Kernig’s sign. The patient was diagnosed with meningitis and admitted under the medical team for further investigation and empirical intravenous antibiotic treatment.

Investigations demonstrated a white cell count of 20.2, with neutrophilia of 17.3. C-reactive protein was 222. Computed tomography of the brain was normal. Lumbar puncture results were negative for meningitis. The patient’s biochemical markers for infection remained elevated and her symptoms did not improve despite anti-microbial therapy.

The patient reported a post-nasal drip on day three of her admission, with persistent right-sided neck pain, and was referred to the otolaryngology team. The patient reported no other nasal symptoms. She noted some mild hoarseness associated with a persistent cough, but no dysphagia, odynophagia, trismus or torticollis. An examination of her neck replicated the findings on admission. Repeat examination of the oropharynx demonstrated leftward uvular deviation on phonation. Flexible nasendoscopy demonstrated the presence of mucopus in the posterior nasal cavity and nasopharynx, with swelling of the right pharyngeal wall. Upon phonation, paralysis of the right vocal cord was noted.

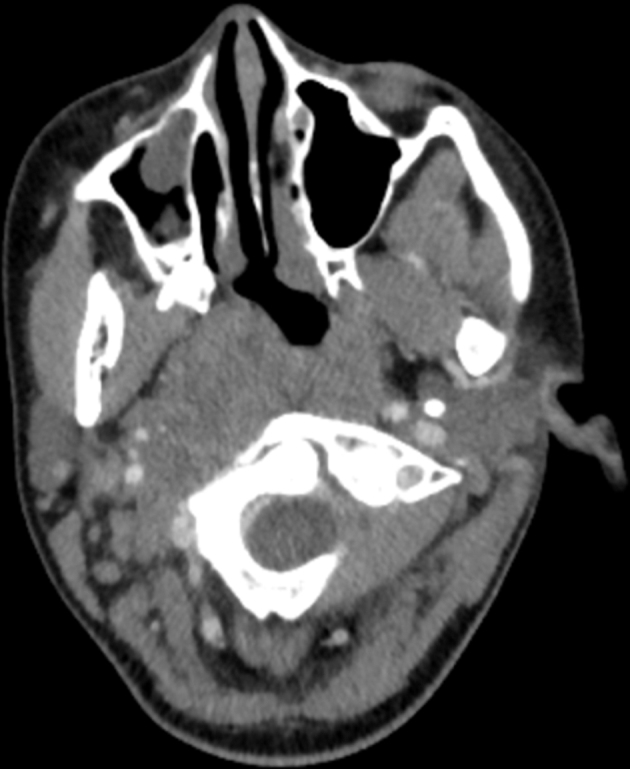

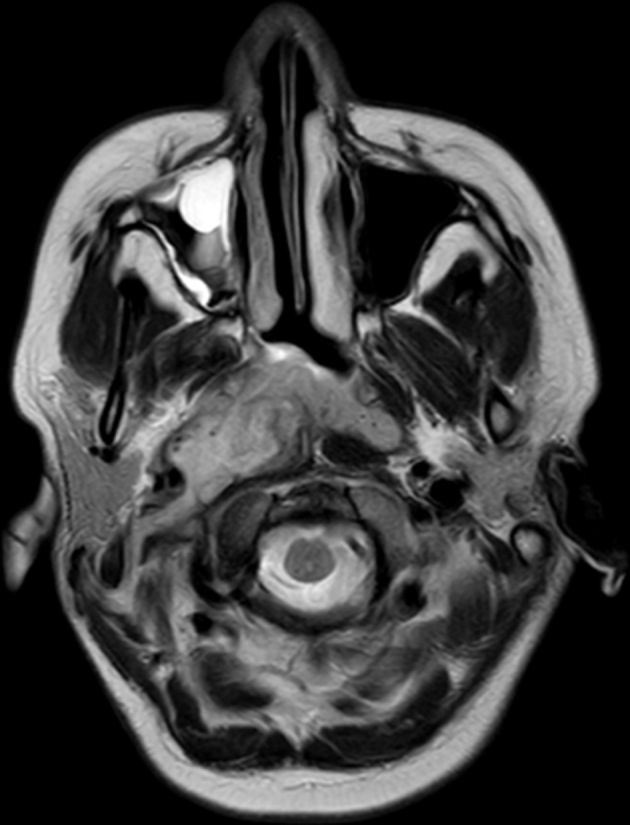

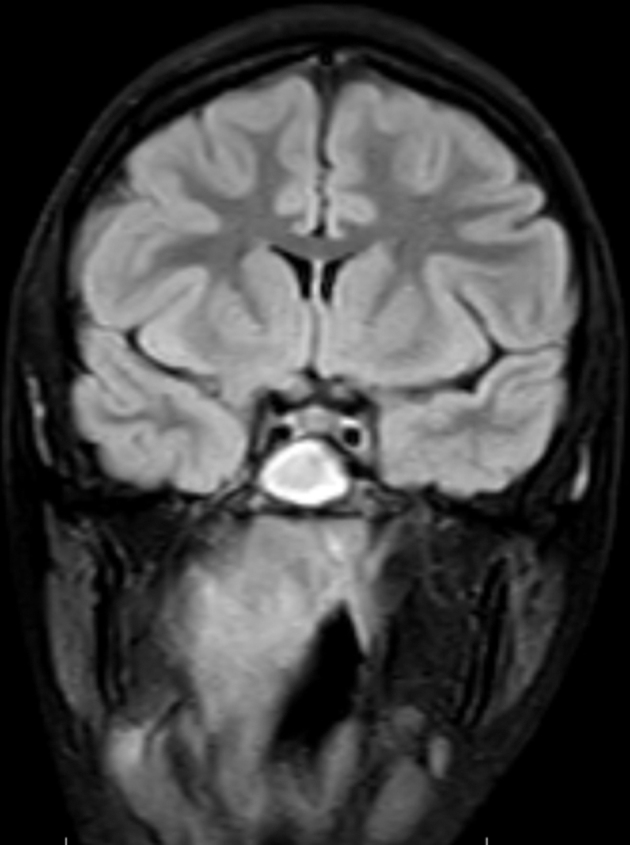

CT was repeated to trace the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. This demonstrated right-sided parapharyngeal oedema, with a collection focused in the nasopharynx, extending to the skull base (Fig 1). This was replicated on magnetic resonance imaging (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the neck with contrast. There is diffuse bulkiness of soft tissue in the region of the right parapharyngeal space with deviation of the pharynx towards the left. Subtle peripheral enhancement is present. Appearances are indicative of a large right parapharyngeal abscess formation.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance image of the brain: sagittal view confirming computed tomography findings.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance image of the brain: coronal view confirming computed tomography findings.

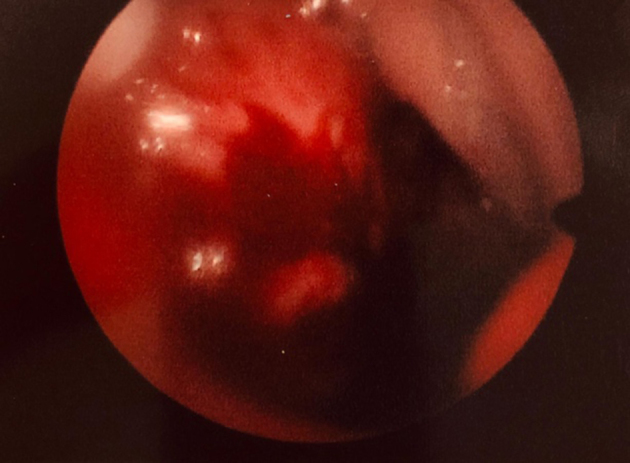

The patient was transferred to the operating theatre to drain the abscess. Owing to the location of the collection on imaging, a transnasal endoscopic approach was planned. A zero-degree rigid endoscope allowed visualisation of the nasal cavities and post-nasal space. Suctioning mucopurulent fluid in the oropharynx and post-nasal space revealed a lesion in the right nasopharynx (Fig 4). Upturned Blakesley forceps were used to obtain tissue samples for histology. This approach resulted in breach into the abscess cavity and drainage of purulent material.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative endoscopic view of right nasopharyngeal lesion.

Tissue biopsies were reported as acute on chronic minor salivary gland sialadenitis following histological analysis: the likely precipitating cause in this case.

Discussion

Parapharyngeal infections carry a significant risk of extensive suppuration. Spread into deep neck spaces is a recognised complication of sialadenitis of the major salivary glands.2 However, parapharyngeal abscess formation secondary to minor salivary gland infection has not been previously reported in the literature.

Our patient presented with atypical symptoms. Her associated headache and photophobia acted as distracting factors, diverting the attention of treating clinicians towards meningitis. In addition, the patient had previously undergone a tonsillectomy, further obfuscating the differential diagnosis. The presence of a post-nasal drip prompted a referral to the otolaryngology team. Although this symptom was likely secondary to insidious discharge from the abscess into the nasopharynx, it was erroneously attributed to sinusitis during initial assessment. Flexible nasendoscopy was instrumental in redirecting the diagnosis back towards parapharyngeal sepsis.

Examination of the vocal cords demonstrated right-sided paralysis. Subtle leftward deviation of the patient’s uvula on phonation suggests that this was due to involvement of the right vagus nerve, rather than the recurrent laryngeal alone. The proximity of the collection to the skull base and jugular foramen could explain this phenomenon. Jugular foramen syndrome (or Vernet’s syndrome), characterised by paresis of cranial nerves IX, X and XI has been previously reported in the literature.3,4 However, there is no previous report of vagus nerve palsy occurring in isolation secondary to a parapharyngeal abscess.

Preoperative review of imaging in this case demonstrated features of an abscess in the paranasopharyngeal space, close to the skull base. Hence, the collection was drained using transnasal endoscopy instead of the traditional transoral or external neck approaches. To date, few have reported use of this technique in the literature.2

The patient was discharged on postoperative day 1 having demonstrated clinical and biochemical improvement. Our experience replicates previous reports of low morbidity and minimal hospitalisation associated with this technique.2

Conclusion

Paranasopharyngeal abscesses may present with atypical features. A high degree of suspicion is required to reach a diagnosis in these cases. Infection within a minor salivary gland can spread into the parapharyngeal space and may be located in unusual or difficult to access regions within the head and neck. Abscess formation can impair vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerve function. Surgical drainage remains the main treatment for parapharyngeal abscesses. The transnasal endoscopic approach is a safe and effective option.

References

- 1.Kauffmann P, Cordesmeyer R, Troltzsch M et al. Deep neck infections: a single-center analysis of 63 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017; (5): e536–e541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolai P, Lombardi D, Berlucchi M et al. Drainage of retro-parapharyngeal abscess: an additional indication for endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2005; (9): 722–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M, Heo Y, Kim T. Vernet’s syndrome associated with internal jugular vein thrombosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2019; (2): 344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solymosi L, Wassmann H, Bonse R. Diagnosis of neurinoma in the region of the jugular foramen: a case report. Neurosurg Rev 1987; (1): 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]