Abstract

Introduction

Statutory duty of candour was introduced in November 2014 for NHS bodies in England. Contained within the regulation were definitions regarding the threshold for what constitutes a notifiable patient safety incident. However, it can be difficult to determine when the process should be implemented. The aim of this survey was to evaluate the interpretation of these definitions by British neurosurgeons.

Materials and methods

All full (consultant) members of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons were electronically invited to participate in an online survey. Surgeons were presented with 15 cases and asked to decide in the case of each one whether they would trigger the process of duty of candour. Cases were stratified according to their likelihood and severity.

Results

In all, 106/357 (29.7%) members participated in the survey. Responses varied widely, with almost no members triggering the process of duty of candour in cases where adverse events were common (greater than 10% likelihood) and required only outpatient follow-up (7/106; 6.6%), and almost all members doing so in cases where adverse events were rare (less than 0.1% likelihood) and resulted in death (102/106; 96.2%). However, there was clear equipoise in triggering the process of duty of candour in cases where adverse events were uncommon (0.1–10% likelihood) and resulted in moderate harm (38/106; 35.8%), severe harm (57/106; 53.8%) or death (49/106; 46.2%).

Conclusion

There is considerable nationwide variation in the interpretation of definitions regarding the threshold for duty of candour. To this end, we propose a framework for the improved application of duty of candour in clinical practice.

Keywords: Duty of candour, Survey, Neurosurgery, Surgery

Introduction

Statutory duty of candour was introduced in November 2014 and applies to all NHS bodies in England in the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014. The intention of this legislation is to ensure openness and transparency with patients when something goes wrong with their care. The process begins with a full and frank account to the patient or next of kin as soon as reasonably practicable after a notifiable patient safety incident has occurred.1 An apology must be provided and an explanation of any further inquiries planned. The results of these inquiries must then be recorded and shared with the patient and/or next of kin. Where applicable, reasonable physical and psychological support must be provided for those affected by the incident.

Contained within the regulation was a definition for what constitutes a notifiable patient safety incident as ‘something unintended or unexpected in a patient’s care that, in the reasonable opinion of a health care professional, could result in or appears to have resulted in either: death (not relating to natural progression of an illness or condition), severe or moderate harm, or prolonged psychological harm’. In deciding whether or not an adverse event requires reporting under the duty of candour, it is essential to determine whether an event was unintended or unexpected. In some situations harm may have been inevitable but preferable to the natural history.

The definitions of harm are the same as those provided by the National Patient Safety Agency. Severe harm is defined as ‘a permanent lessening of bodily, sensory, motor, physiologic or intellectual functions, directly related to the incident’; moderate harm as ‘resulting in a moderate increase in treatment, and significant but not permanent harm’; and prolonged psychological harm as ‘psychological harm experienced or likely to be experienced for at least 28 days’.

Underreporting of duty of candour risks a failure to comply with legislation, which is a criminal offence. The Care Quality Commission is able to bring prosecutions for breaches without prior warning, leading to fines or other actions.1 Overreporting will, at the least, unnecessarily increase administrative burden. There are also concerns regarding maintenance of the doctor–patient relationship and risk of litigation when telling a patient that something has gone ‘wrong’ with their treatment.

The aim of this survey was to evaluate the interpretation of these definitions by British neurosurgeons.

Materials and methods

We adopted an online survey-based cross-sectional study design to canvas opinion on what constitutes a notifiable patient safety incident among British neurosurgeons.

Participants

All full (consultant) members of the Society of British Neurosurgeons were electronically invited to participate in an online survey in May 2018. One reminder was sent to members, and the survey was closed one month after distribution. Unique identifiers were used to ensure each member was only able to complete the survey once.

Survey

We developed the online survey using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). Members were presented with a series of cases and asked to decide for each one whether they would trigger the process of duty of candour. The cases were created by a working group of five neurosurgeons (HJM, PS, NK, BS and LT) to reflect real-life scenarios, and were stratified according to their likelihood and severity by consensus (Box 1).

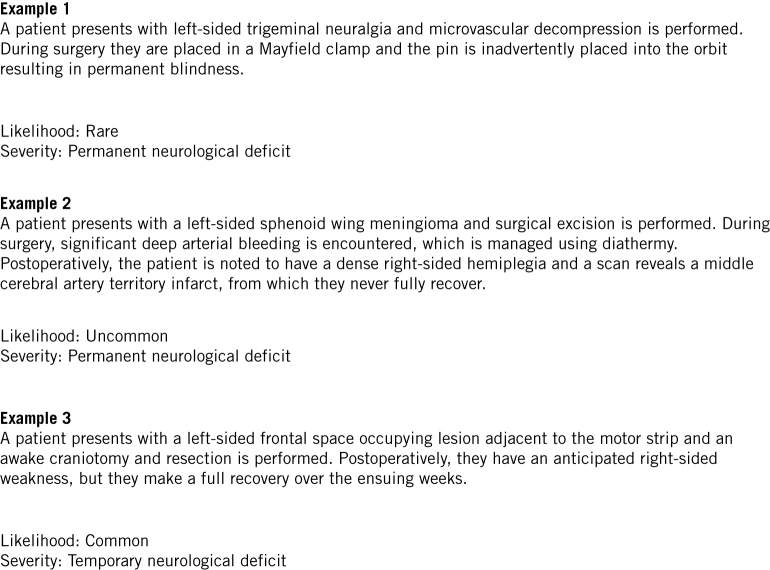

Box 1.

Examples of cases stratified according to their likelihood and severity.

The likelihood of adverse events was grouped into three categories: common (more than 1/10); uncommon (1/10 to 1/1000); or rare (less than 1/1000). The frequency intervals for each of these categories were drawn from the European Commission nomenclature for communicating frequency of adverse effects of drugs, but the number of categories was reduced from five to three for simplicity.2

The severity of adverse events was grouped into five categories as: death, permanent neurological deficit (lasting more than a month), temporary neurological deficit or increase in hospital stay or return to theatre, pain or psychological harm (lasting more than a month), or requiring outpatient follow-up alone. These categories were adapted from the duty of candour legislation categories of death, severe harm, moderate harm or prolonged psychological harm, with a further category for adverse events that simply required outpatient follow-up.

In all, each member was presented with 15 cases encompassing each combination of adverse event likelihood and severity. All responses were anonymised, collected and consolidated on a single spreadsheet for analysis.

Data analysis

The percentage of members who would trigger the process of duty of candour was calculated for each combination of adverse event likelihood and severity.

Results

In all, 106/357 (29.7%) members participated in the survey. The percentage of members who would trigger the process of duty of candour in each combination of adverse event likelihood and severity is summarised in Table 1. Responses varied widely, with almost no members triggering the process of duty of candour in cases where adverse events were common and required only outpatient follow-up (7/106; 6.6%) and almost all members doing so in cases where adverse events were rare and resulted in death (102/106; 96.2%). There was clear equipoise in triggering the process of duty of candour in cases where adverse events were unlikely and resulted in temporary neurological deficit or increase in hospital stay or return to theatre (38/106; 35.8%), permanent neurological deficit (57/106; 53.8%), or death (49/106; 46.2%).

Table 1.

Percentage of members that would trigger the process of duty of candour in each combination of adverse event likelihood and severity.

| Severity of adverse effect | Likelihood during course of disease or treatment | ||

| Common (> 1/10) (%) | Uncommon (1/10–1/1000) (%) | Rare (< 1/1000) (%) | |

| Outpatient follow-up only | 7 | 7 | 83 |

| Pain or psychological harm (lasting more than 1 month) | 17 | 15 | 95 |

| Temporary neurological deficit or increase in hospital stay or return to theatre | 4 | 36 | 96 |

| Permanent neurological deficit (lasting more than 1 month) | 14 | 46 | 96 |

| Death | 19 | 46 | 96 |

Discussion

Principal findings

Following the events at Mid-Staffordshire NHS Trust, a public enquiry by Sir Robert Francis QC uncovered appalling patient care. The report found that a systemic lack of openness, transparency and candour compounded these failings, and the introduction of a statutory duty of candour was among the report’s most important recommendations.1

In this cross-sectional survey we have demonstrated considerable nationwide variation in the interpretation of definitions regarding the threshold for duty of candour; this has important implications, with some providers at risk of financial and legal penalties and others unduly burdened by the associated administrative processes.

The greatest equipoise occurred where adverse events were unlikely and resulted in temporary neurological deficit or increase in hospital stay or return to theatre, permanent neurological deficit or death. These adverse events reflect complications that would likely be explicitly covered during the consent process, and it can be particularly difficult to decide whether or not to trigger duty of candour in these cases.3 However, while the definitions within the statutory duty of candour are open to interpretation, it is pertinent that the Care Quality Commission guidance specifically includes case examples involving recognised and consented-for complications.1

Limitations

The main limitation of the present study is the small sample size and low response rate (29.7%). Although all members of the Society of British Neurosurgeons were invited to participate in the survey, neurosurgeons may have self-selected if they had a particular interest in duty of candour, thus introducing response bias. Nonetheless, the principal finding of the survey that there is nationwide variation in the interpretation of definitions regarding the threshold for duty of candour is likely to remain valid.

Proposed framework

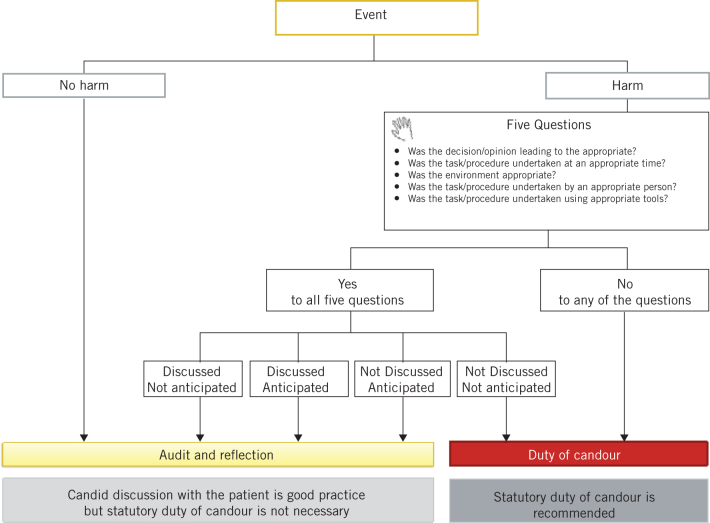

To provide clarification on the threshold for duty of candour, we propose a framework for improved application in clinical practice (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed framework for duty of candour.

Step 1: the framework begins by asking whether the event resulted in harm. In cases where an event has not caused harm then audit and reflection, together with learning through appropriate local clinical governance process, is recommended.

Step 2: if an event has resulted in harm, the framework then poses five questions: was the decision leading to the task appropriate? Was the task or procedure undertaken at an appropriate time? Was the environment appropriate? Was the task or procedure undertaken by an appropriate person? Was the task or procedure undertaken by utilising the appropriate tools? In cases where the answer to one or more of these questions is unsatisfactory, then duty of candour is recommended.

Step 3: if an event has resulted in harm, despite an appropriate decision and timely action delivered in an appropriate place by the right person and with correct equipment, then consideration should be given to whether an event was discussed and/or anticipated beforehand.

Consenting involves discussion of uncommon (1/10 to 1/1000) and rare (less than 1/1000) risks, which while discussed are not routinely anticipated. Occurrence of these ‘discussed but not anticipated’ events does not require a duty of candour but audit and reflection, together with learning through appropriate local clinical governance process, is recommended.

Consenting will also involve discussion of adverse events that occur commonly (more than 1/10) following surgery and are therefore anticipated. For example, removal of a neuroma from a nerve will commonly result in loss of function of the nerve. These events are ‘discussed and anticipated’. Routine audit of clinical outcome may be all that is required in these cases.

A failure to discuss fully adverse events that occur commonly (more than 1/10) during consenting can lead to events that are ‘not discussed but anticipated’. This is a communication issue, and audit and reflection, together with learning through appropriate local clinical governance process, is recommended.

An appropriately consented patient may suffer harm from an adverse event that was neither discussed nor anticipated. This event, often the result of an accident, a misadventure or an unplanned step, will be ‘not discussed and not anticipated’. In these cases, duty of candour is recommended. Invoking duty of candour in this situation does not imply negligence or substandard care; the action could have been undertaken in good faith and could be unavoidable.

Conclusion

In the present study we have demonstrated considerable nationwide variation in the interpretation of definitions regarding the threshold for duty of candour, with important financial, legal and administrative implications. It is hoped that the proposed framework will allow for the more consistent application of duty of candour in clinical practice, particularly in cases involving recognised and consented-for complications.

References

- 1.Wijesuriya JD, Walker D. Duty of candour: a statutory obligation or just the right thing to do? Br J Anaesth 2017; : 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchter RB, Fechtelpeter D, Knelangen M et al. . Words or numbers? Communicating risk of adverse effects in written consumer health information: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014; : 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler R. Candour for surgeons: the absence of spin. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014; : 420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]