Abstract

Objective

Elastofibroma is a rare soft-tissue tumour. This study retrospectively analysed and summarised the clinical, imaging and typical pathological features, together with the short- and long-term surgical outcomes of patients with pathologically confirmed soft-tissue elastofibroma to improve their management.

Materials and methods

We enrolled 73 patients with pathologically confirmed soft-tissue elastofibroma from January 2010 to December 2018. The general, clinical, diagnostic and treatment-related data, operation notes, pathological examination results and follow-up status were obtained by reviewing inpatient medical records. Disease onset age, sex, tumour location and size were statistically analysed using the chi square and rank sum tests.

Results

A total of 90 lesions from 73 patients were examined. Among these, 56 patients had single lesions: 27 were under the right scapula, 26 were under the left scapula, 1 at the umbilicus, 1 on the aortic valve, 1 on the right hip and 17 at the bilateral inferior angles of the scapula. The average age at onset was 56.4 years (range: 6–82 years). The male-to-female incidence ratio was about one to three. Tumour diameter and follow-up duration ranged from 2cm to 12cm and from one month to nine years, respectively; recurrence was not observed. The main postoperative complication was wound effusion, occurring in 24 sites among the 90 lesions, corresponding to an incidence rate of 26.7%.

Conclusions

A correct diagnosis of elastofibroma can be made prior to surgical resection by examining typical clinical features and characteristic imaging findings. Short- and long-term outcomes of local excision are good, with no further recurrence.

Keywords: Elastofibroma, X-ray computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Ultrasonography, Pathological examination, Tumour

Introduction

Elastofibroma was first reported and named by Jarvi et al in 1961.1 It was classified as a benign fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumour in 2002 in the World Health Organization classification of soft-tissue tumours.2 It was named elastofibroma dorsi because all the initial lesions occurred in the back. Since then, less than 600 cases have been reported.3–6 Approximately 99% of elastofibromas are located in the soft tissue in the inferior angles of the scapulae, deep in the latissimus dorsi, in the serratus anterior and rhomboids, and lateral to the ribs and intercostal muscles.7 Elastofibromas have been reported to occur in other rare sites, including the hands,8 feet,9 mouth,10 joints,11 mediastinum, 12 and aorta.13 However, elastofibromas occurring in the umbilical region and buttocks have not been reported.

Since its first description, elastofibroma has received little attention in the medical literature, and only a few studies have analysed its aetiology and clinical characteristics. We aimed to summarise the clinical, imaging and pathological features, and the short- and long-term surgical outcomes of elastofibroma, to provide a basis for early diagnosis and treatment methodologies.

Materials and methods

Patients were included if they had histopathologically confirmed elastofibroma and if they could be followed up. Those with incomplete pathology data were excluded. A retrospective review of the pathological database of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University from 2010 to 2018 showed a total of 172,047 patients with soft-tissue tumours, of whom 73 patients with elastofibroma were treated with surgery and diagnosed through pathology (Table 1). The inpatient medical records of 25 patients with elastofibroma were reviewed and general case data, clinical diagnosis and treatment data, surgical records, pathological examination results and follow-up information were obtained. The remaining study participants were outpatients whose basic data were obtained through follow-up telephone interviews.

Table 1.

Clinical data of 73 patients with elastofibroma dorsi.

| Patient | Date | Age (years) | Sex | Location | Size (cm) | Symptoms | Haematoma |

| 1 | 2010 | 64 | M | L | 5 × 4 × 4 | clunking | |

| 2 | 2011 | 48 | F | R | 2 × 2 × 1 | clunking | |

| 3 | 2011 | 56 | F | L | 9 × 6.5 × 5.5 | swelling | (+) |

| 4 | 2011 | 49 | F | R | 6 × 4 × 3 | pain + clunking | |

| 5 | 2011 | 35 | M | L | 3 × 2 × 2 | clunking | |

| 6 | 2011 | 39 | M | R | 6 × 4 × 3 | swelling | |

| 7 | 2011 | 60 | F | B | 3 × 2 × 1 | pain + swelling + clunking | |

| 11 × 7 × 4 | (+) | ||||||

| 8 | 2011 | 6 | M | R | 3 × 2 × 1 | clunking | |

| 9 | 2011 | 57 | F | B | 2.5 × 2.5 × 1 | swelling | |

| 12 × 10 × 5 | (+) | ||||||

| 10 | 2011 | 62 | F | B | 6 × 5 × 3 | pain + swelling | |

| 11 × 6 × 3 | (+) | ||||||

| 11 | 2012 | 51 | F | L | 7 × 6 × 5 | pain + swelling | |

| 12 | 2012 | 41 | F | L | 2 × 1 × 1 | clunking | |

| 13 | 2012 | 79 | F | R | 3 × 2 × 1.6 | clunking | |

| 14 | 2012 | 56 | F | R | 5 × 4 × 3 | pain + clunking | |

| 15 | 2012 | 55 | F | L | 6.8 × 5 × 4 | pain + swelling | |

| 16 | 2012 | 55 | F | R | 4 × 3.5 × 3 | clunking | |

| 17 | 2012 | 43 | M | L | 3 × 2.5 × 1 | clunking | |

| 18 | 2012 | 73 | M | R | 2 × 1.5 × 1 | clunking | |

| 19 | 2012 | 47 | F | R | 5 × 4 × 1 | clunking | |

| 20 | 2013 | 45 | F | B | 9 × 7 × 4 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 8 × 6 × 3 | (+) | ||||||

| 21 | 2013 | 57 | F | R | 5 × 4 × 3 | clunking | |

| 22 | 2013 | 58 | F | R | 10 × 4 × 3 | swelling | (+) |

| 23 | 2013 | 64 | F | R | 8.5 × 7.5 × 3 | swelling | (+) |

| 24 | 2013 | 64 | F | L | 11 × 8 × 4 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 25 | 2013 | 59 | F | B | 8 × 5 × 3 | swelling + clunking | |

| 5 × 4 × 3 | |||||||

| 26 | 2013 | 65 | F | B | 3 × 2.5 × 0.7 | clunking | |

| 3.5 × 2.5 × 1.3 | |||||||

| 27 | 2013 | 59 | M | L | 6.5 × 4 × 1.8 | pain | |

| 28 | 2013 | 60 | F | R | 5 × 5 × 4 | clunking | |

| 29 | 2013 | 65 | F | R | 5 × 3 × 1.5 | clunking | |

| 30 | 2013 | 60 | F | L | 5 × 4 × 3 | clunking | |

| 31 | 2013 | 71 | F | R | 5 × 4 × 3 | clunking | |

| 32 | 2013 | 60 | F | R | 9 × 7 × 4 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 33 | 2013 | 60 | F | R | 9 × 7 × 5 | swelling | (+) |

| 34 | 2013 | 81 | F | L | 6 × 5 × 4 | swelling + clunking | |

| 35 | 2013 | 60 | F | B | 7 × 5 × 2 | pain + swelling | |

| 8 × 6 × 4 | (+) | ||||||

| 36 | 2014 | 67 | F | L | 8 × 5 × 2.5 | swelling | |

| 37 | 2014 | 73 | F | B | 7 × 5 × 2 | swelling | |

| 9 × 5 × 3 | (+) | ||||||

| 38 | 2014 | 64 | F | L | 10 × 7 × 4 | swelling | (+) |

| 39 | 2014 | 58 | F | hip | 5 × 3 × 1.5 | ||

| 40 | 2015 | 55 | F | R | 8 × 4 × 5 | pain + swelling | |

| 41 | 2015 | 56 | F | L | 10 × 7 × 5 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 42 | 2015 | 82 | M | L | 5 × 4 × 4 | clunking | |

| 43 | 2015 | 22 | M | L | 2 × 1 × 0.5 | clunking | |

| 44 | 2016 | 43 | M | L | 2.5 × 2 × 1 | clunking | |

| 45 | 2016 | 57 | M | R | 9 × 7.5 × 6 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 46 | 2016 | 72 | F | R | 4 × 3 × 2 | clunking | |

| 47 | 2016 | 46 | M | B | 8 × 4.5 × 3 | pain + swelling | |

| 7 × 5.5 × 5 | |||||||

| 48 | 2016 | 65 | F | B | 6 × 5 × 4 | pain + swelling | |

| 8.5 × 6 × 4.5 | |||||||

| 49 | 2016 | 55 | F | L | 6 × 4 × 1 | clunking | |

| 50 | 2016 | 50 | F | R | 2.8 × 2.2 × 1.5 | clunking | |

| 51 | 2016 | 58 | F | L | 6 × 5 × 4 | pain | |

| 52 | 2016 | 53 | F | B | 7 × 5.5 × 4.5 | pain + swelling | |

| 6.5 × 4.5 × 2 | |||||||

| 53 | 2016 | 56 | M | R | 8.5 × 6 × 4 | pain + swelling | |

| 54 | 2016 | 59 | F | L | 9 × 6 × 3.5 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 55 | 2016 | 40 | M | aorta | 1 × 0.6 × 0.3 | ||

| 56 | 2016 | 77 | F | L | 11 × 7 × 6 | swelling | (+) |

| 57 | 2017 | 71 | F | R | 5 × 4 × 3 | clunking | |

| 58 | 2017 | 43 | F | B | 8 × 4 × 3 | swelling | |

| 8 × 6 × 5 | (+) | ||||||

| 59 | 2017 | 75 | F | L | 4 × 3.5 × 2.5 | clunking | |

| 60 | 2017 | 53 | M | L | 10 × 7 × 3.5 | swelling | (+) |

| 61 | 2017 | 52 | M | navel | 2 × 1 × 1 | ||

| 62 | 2017 | 72 | F | L | 4 × 3 × 2 | clunking | |

| 63 | 2017 | 25 | F | R | 6 × 1.5 × 1 | discomfort | |

| 64 | 2017 | 48 | M | L | 10 × 9 × 4 | swelling | (+) |

| 65 | 2017 | 62 | F | R | 6 × 4 × 3 | clunking | |

| 66 | 2018 | 41 | M | R | 8 × 5 × 2 | pain + swelling | |

| 67 | 2018 | 71 | F | B | 6.5 × 6 × 4 | pain + swelling | |

| 7 × 5 × 3.5 | |||||||

| 68 | 2018 | 57 | M | L | 6 × 5 × 3 | pain + swelling | |

| 69 | 2018 | 68 | F | B | 5 × 4 × 1 | swelling | |

| 10 × 12 × 6 | (+) | ||||||

| 70 | 2018 | 54 | F | R | 8.5 × 8.5 × 2 | swelling | |

| 71 | 2018 | 37 | F | B | 6 × 4 × 3 | pain + swelling | |

| 10 × 7 × 3 | |||||||

| 72 | 2018 | 62 | F | B | 7 × 4 × 3 | pain + swelling | (+) |

| 8 × 5 × 4 | |||||||

| 73 | 2018 | 53 | F | B | 10 × 5 × 5 | swelling | (+) |

| 8 × 6 × 4 |

B, bilateral at the angles of the scapulae; F, female; L, angle of the scapula on the left back; M, male; R, angle of the scapula on the right back.

We compared common sites, male-to-female ratio, incidences of unilateral and bilateral disease, and size of lesions on left and right sides. Statistical Program for Social Sciences 21.0 was used for analysis, measurement data were expressed as x ± s, and the rank sum test was used to compare between two samples. The chi square test was used for comparison of constituent ratios. The significance level was calculated at P = 0.05.

Results

General case characteristics

Our population included 56 patients with single lesions: 27 were at the angle of the scapula on the right back, 26 at the angle of the scapula on the left back, 1 in the umbilicus; 1 in the aortic valve and 1 in the right hip. Of these, 17 were bilateral lesions, all located at the angles of the scapulae. Disease sites included locations below the scapula, aortic valve, umbilicus and buttock. Among the patients, 19 were male and 54 were female, with a male-to-female ratio of 1 : 2.84. Patient age ranged from 6 years to 82 years, with an average age of 56.3 years. Length of disease history ranged from one month to seven years. Regarding occupation, the cohort included 5 construction labourers and 31 ordinary labourers; the others had no history of heavy physical labour. The most common symptoms were pain, swelling and significant tissue enlargement in a short time. Physical examination showed 59 cases of palpable skin masses under the scapulae: 37 with significant growth in a short time, 4 with limited upper-limb movement on the affected side, 26 with tenderness and 14 with no significant symptoms. All 90 lesions were completely excised by surgery. The follow-up period ranged from one month to nine years; no recurrence was observed.

Elastofibroma lesion characteristics

Among the 90 lesions, 87 were located at the angles of the scapulae on the back, posterior to the serratus anterior muscle, anterior to the rhomboid muscle and in the fat spaces outside the ribs and intercostal muscles. The lesions were oblate ellipsoid or semicircular, with a wide base adjacent to the ribs and intercostal muscles. Of the remaining three lesions, one was located in the umbilicus, one in the aorta and one on the right hip. The total incidence was about 0.04%; incidence rates in males and females were about 0.01% and 0.03%, respectively. Incidence was 2.84 times higher in females than in males. Differences in constituent ratios of the numbers of males and females with elastofibroma were not significant (chi square 0.029, P > 0.05; Table 2). Additionally, the data showed that the constituent ratios of single and bilateral disease of the elastofibroma dorsi were 76% and 24%, respectively. Lesions in the hips, umbilicus and aorta were not included in the analysis. Unilateral elastofibroma dorsi was more common, and the differences in the constituent ratios of unilateral and bilateral disease were significant (chi square 4.136, P < 0.05; Table 3). Furthermore, the data from this group showed that the left and right lesions often had different sizes and the right lesions were larger than the left lesions. The maximum diameter of the right lesions ranged between 2cm and 12cm, with a thickness of about 1–6cm; average volume (mean ± standard deviation) was about 143.24 ± 147.80 cm3. The maximum diameter of the left lesions ranged between 2.5cm and 10cm, with a thickness of about 0.7–6cm; average volume was about 121.59 ± 116.95cm3. The volumes of the left and right lesions were significantly different (z = 1.000, P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Detection of elastofibroma.

| Sex | Patients with disease (n) | Patients without disease (n) | Total |

| Male | 19 | 46,280 | 46,299 |

| Female | 54 | 125,694 | 125,748 |

Table 3.

Examination of sides with elastofibroma dorsi.

| Sides | Male | Female | Total |

| Bilateral | 1 | 16 | 17 |

| Unilateral | 16 | 37 | 53 |

Note: The hips, umbilicus and aorta were not included in this examination of diseased sides.

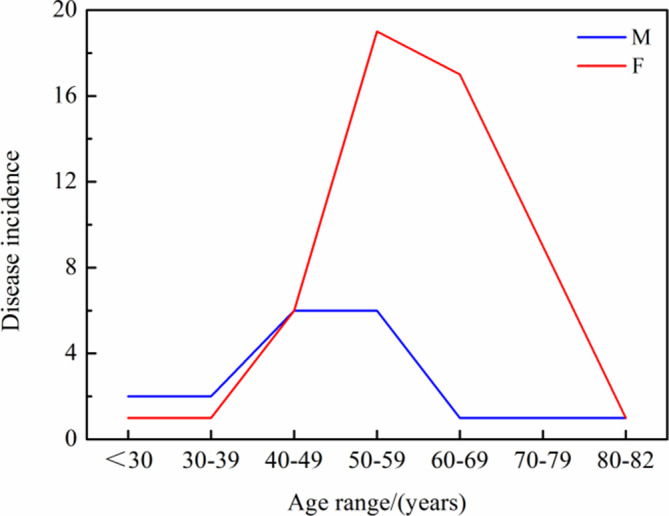

Age and distribution of disease course

The age distribution among the 73 patients was three 0–29 years, three over 29–39 years, twelve 40–49 years, twenty-five 50–59 years, eighteen 60–69 years, ten 70–79 years and two 80–82 years (Fig 1). It can be concluded that the high-risk groups included women aged between 50 and 70 years and men aged between 40 and 60 years. The number of women aged over 40 years with elastofibroma was significantly higher than that of men aged over 40 years. Distribution of length of the disease course was 32 cases of ≤ 1 year; 15 of > 1–2 years, 10 of > 2–4 years, 7 of > 4–6 years, 6 of > 6–8 years and 3 of > 8–10 years.

Figure 1.

Age and disease course distribution of the cohort (F, female; M, male).

Ultrasound diagnosis

Among the 73 patients, 60 underwent preoperative ultrasound examination. High-frequency colour Doppler ultrasound clearly showed the overall characteristics of the lesions. In 60 cases, the lesion size was between 2.0 × 1.1 × 1.1cm and 10.0 × 12.0 × 6cm; these were located in the deep layer of the muscularis, adjacent to the ribs, presenting as masses with oblate or irregular shapes, uneven echoes, unclear boundaries without apparent capsules, unclear boundaries with surrounding tissues, uneven alternate arrangement of high and low internal echoes (adipose tissue and elastic fibres, respectively), cord-like high echoes arranged along the long axis of the lesions and no significant blood hypointensity (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Ultrasound showing the characteristic findings.

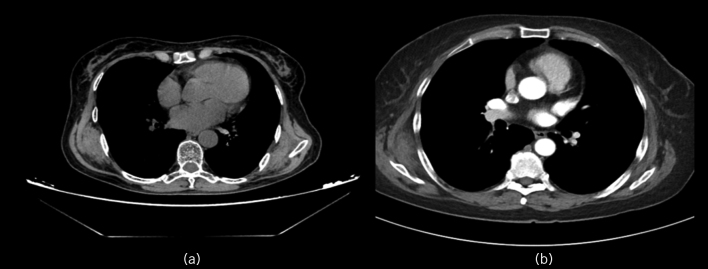

Computed tomography diagnosis

Computed tomography (CT) was performed preoperatively for 36 lesions in 27 of the 73 patients. The sizes of these 36 lesions ranged from 1.9 × 1.3 × 1.1cm to 10.0 × 12.0 × 6cm. Of these, eight cases involved bilateral lesions in the angle of the scapulae, eight involved right single lesions, eleven involved left single lesions and one involved aortic elastofibroma. The boundary of the tumour was clear, indicating that the tumour itself was not related to the adjacent muscle tissue and that the tumour only showed signs of displacement and compression. No damage to the adjacent ribs or scapula was observed, which was typical of the swelling growth of benign tumours. Plain CT of the lesions showed soft-tissue masses with densities similar to those of the adjacent muscle, which indicated lesions containing a large number of fibres and mixed fat tissue in the fibrous tissue. Based on CT characteristics, which involved a zebra pattern of fat density images (fig 3a) with high (elastic fibres) and low (adipose tissue) density components visible inside the lesion, we identified the tumour as an elastic fibroma. CT plain scans of the lesions showed soft-tissue masses with density similar to that of the adjacent muscle but less uniform. The adjacent muscle was pressed outward in an arc shape without involvement of local ribs. A zebra pattern of fat density images (fig 3a) with high (elastic fibres) and low (adipose tissue) density was visible inside the lesion. On enhanced CT, the masses and fat stripes were not enhanced. No definite enhancement was found in the lesions of the two patients who underwent enhanced CT (fig 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Computed tomography (CT) showing zebra pattern of fat density images with high (elastic fibres) and low (adipose tissue) density areas inside the lesion. (b) Contrast enhanced CT showing no definite enhancement.

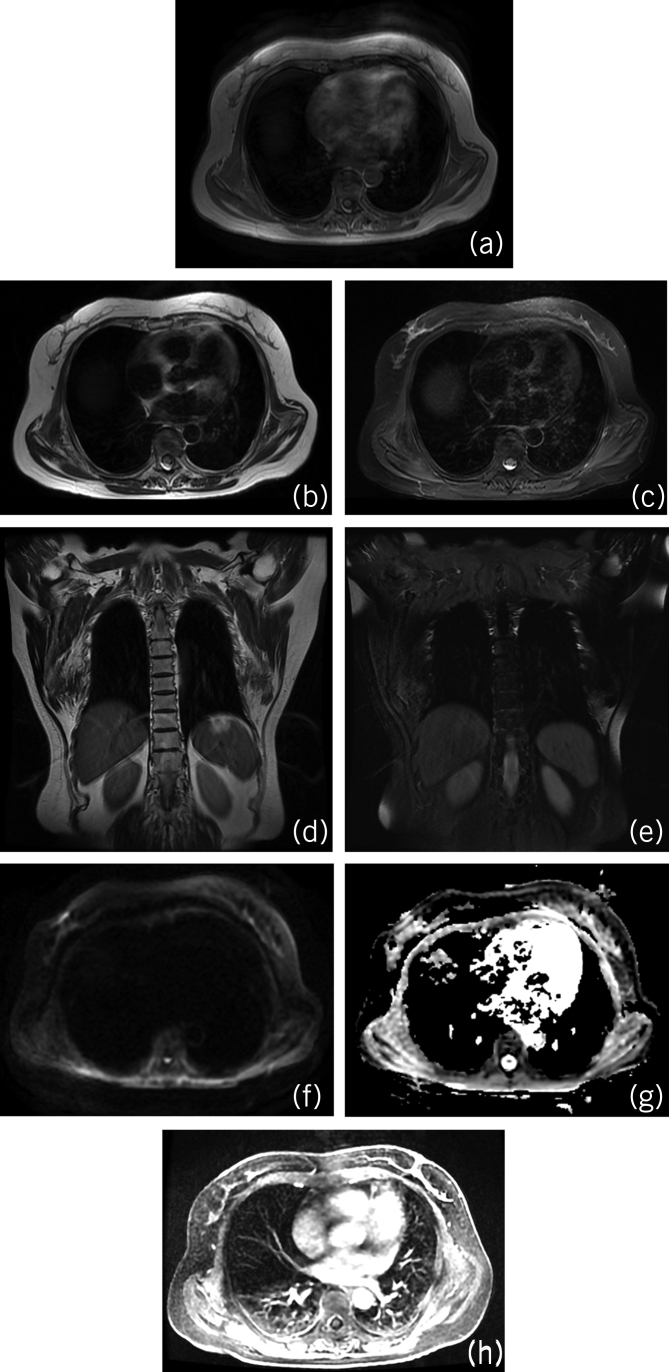

Magnetic resonance imaging

Plain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed preoperatively for 26 lesions in 18 of the 73 patients, which showed that the base of the tumour was closely connected with the posterior chest wall, with clear boundaries between the tumour periphery and surrounding tissues; no sign of invasion of the adjacent bone was observed. MRI allows characterisation of the site and morphostructural features of the typical elastofibroma dorsi, particularly with T2-weighted sequences, owing to its ability of differentiating elastofibroma from other soft-tissue lesions of the infrascapular region. The fibrous tissue was isointense compared with the skeletal muscle on both T1- and T2-weighted images, whereas the fatty tissue was hyperintense on T1-weighted image (fig 4a). Axial and coronal T2-weighted MRI showed hyperintensity of the intralesional stripes (figs 4b,d). However, on axial and coronal T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequence, the stripe-like hyperintensity of the lesion was suppressed to significant hypointensity (fig 4c,e). Diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient revealed isointensity of the lesions (fig 4f,g). Partial enhancement was detected on contrast-enhanced images (fig 4h). MRI plain scans were performed prior to surgery on 26 lesions in 18 of the 73 patients, and showed that the base of the tumour was closely connected with the posterior chest wall, with clear boundaries between the tumour periphery and surrounding tissues, and no sign of invasion of adjacent bone was seen. Masses were seen under bilateral scapulae with isointensity on T1WI (fig 4a) and isointensity on T2WI (fig 4b). The internal signal was not uniform, with stripe-like T1WI hyperintensity and T2WI hyperintensity. In the fat suppression sequence, the stripe-like hyperintensity in the lesions was suppressed to show significant hypointensity (fig 4c). The signal of the tumour tissue was similar to that of surrounding muscles, and the signal of the adipose tissue in the tumour was similar to that of subcutaneous adipose tissue (fig 4c,d). Because MRI is more sensitive to soft tissue it is the first choice for soft-tissue tumours containing fat.

Figure 4.

(a) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing isointensity of the fibrous tissue (relative to the skeletal muscle) and hyperintensity of the fatty tissue. (b, d) Axial and coronal T2-weighted MRI showing hyperintensity of the intralesional stripes. (c, e) Axial and coronal T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI showing significant hypointensity of the intralesional stripes. (f, g) Diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient revealing isointensity of the lesions. (h) Partial enhancement of the tumour following gadolinium injection.

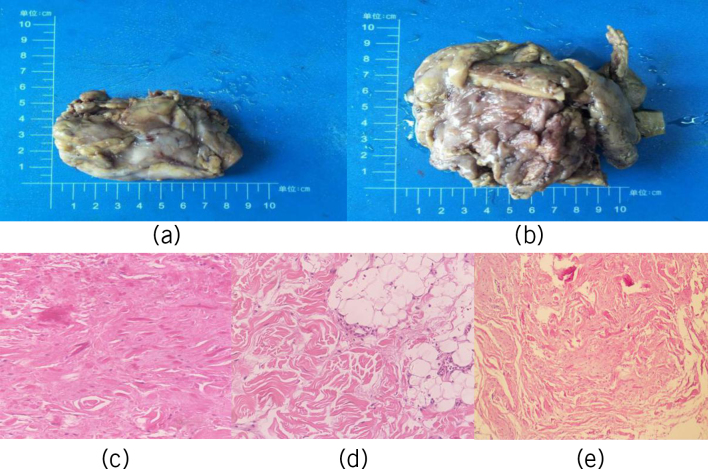

Histological features of elastofibroma on pathological examination

Pathological examination of elastofibroma showed elastic masses that were irregular, flat shuttle-shaped or oblate, without capsules, with unclear boundaries, covered with adipose tissue on the surface, pale white in the section and with visible yellow adipose tissue (fig 5a,b). Microscopically, we noted fascicular collagenous fibres, thick elastic fibres, focal adipose tissue, scattered and sparse fibroblasts and slightly hypertrophic nuclei. The following important pathological features of the tumour were noted: a large number of heterogeneous elastic fibres with varying degrees of degeneration among the collagen fibres, elastic fibres that were bulkier than normal, diameter of 20m, consistent contortion of the long axis of the elastic and collagen fibres; thick elastic fibres that were beaded or serrated and some spherical elastic fibres, known as the elastic balls, that were of uneven distribution and shape (figs 5c–e). The tumours were composed of collagen fibres and elastic fibres in adipose connective tissue stroma. Collagen fibres had hyalinisation mixed with wavy, beaded, broadband-like, serrated, irregular elastic fibres of different sizes and mature adipose tissue (figs 5c–e).

Figure 5.

(a, b) Gross examination findings of the tumours. (c–e) Histopathological appearance of the tumours.

Discussion

Aetiology and treatment

Opinions still differ about whether elastofibroma is a true tumour or a proliferative tumour-like lesion. Most scholars believe that elastofibroma dorsi is caused by repeated mechanical friction between the inferior angle of the scapula and chest wall. Long-term damage to fibrous connective tissue and blood vessels causes disruptions in local blood and nutrient circulation, leading to compensatory hyperplasia of the fibrous tissue.14 However, some scholars believe that the disease has a familial aspect. Akçam et al reported three patients showing significant familial tendency for elastofibroma and suggested that elastofibroma is related to chromosome instability.15 Nagamine et al reported that one-third of 170 patients had positive family histories;16 however, none of our cases showed a family history. Hernandez et al found that, in elastofibroma, the DNA sequences of chromosomes 1p, 13p, 19p, and 22p were lost;17 contrastingly, Nishio et al showed an increased copy number of DNA on the long arm of the X-chromosome,18 which indicates that fibroelastomas contain genetic alterations. These histological findings all indicated that elastofibroma comprises a real tumour process and is not a degenerative disease or a result of connective tissue ageing. In addition, Yoshida et al reported the first case of elastofibroma occurring at the incision site of subscapular surgery six years after thoracoscopic surgery.19 Our case series also included elastofibromas occurring at uncommon sites, including the umbilicus, buttocks and aorta. These findings suggest that the disease may be caused by other pathogenic or comprehensive factors. At present, no uniform standards are available for surgical indications of elastofibroma. Faccioli et al suggested that surgical treatment is necessary only for cases with limited function, significant pain or masses larger than 5cm.20 At present, surgical resection is considered to be the first choice of treatment for elastofibroma.21 Surgery should be performed on patients with large tumours or those showing symptoms. Biopsy should be performed on subclinical patients with atypical or asymptomatic lesions to exclude the possibility of sarcoma; regular follow-up should also be performed.

Epidemiology

We searched the PubMed, Medline, Springer, Elsevier, Wiley, EI and NCBI databases before December 2018 with the term ‘elastofibroma’ for reports of cases and small case series published on this subject. Literature inclusion criteria included elastofibroma that were confirmed by pathology and had adequate case data. Literature exclusion criteria included elastofibroma with only a clinical diagnosis without pathological confirmation and cases with incomplete unobtainable clinical data. No more than 600 previously reported cases were obtained(3-6). Elastofibroma is a rare benign soft-tissue tumour, and in 99% of cases, the tumours were located in the bilateral inferior angles of the scapulae, showing significant site tendency, and elastofibromas were rare in other sites. Till date, elastofibroma in the buttock or umbilical region has not been reported in the literature. In this series, 70 cases occurred in the bilateral subscapularis, 1 in the aorta, 1 in the buttock, and 1 in the umbilical region, which indicates that elastofibroma is likely to occur in other parts of the body besides subscapularis and provides certain reference for clinical diagnosis and pathophysiological research of the disease. The onset age of elastofibroma is over 40 years, and only one case of elastofibroma has been reported to occur in a patient younger than 30 years (at 6 years)(22). In our group, 1 patient developed elastofibroma at 6 years of age, 1 at 22 years of age, and 1 at 25 years of age, showing that elastofibroma onset tended to happen at a young age. The incidence of elastofibroma appears to differ according to region; elastofibroma is rare in European and American countries. However, in the Japanese mainland of Okinawa and its offshore islands of Tonaki-jima and Aguni-jima, the occurrence of elastofibroma is relatively high, whereas the number of cases reported in other regions is relatively small.16 This discrepancy may be partly due to the difference in recognition of this entity between the UK and Japan; however, genetic factors may also play a role in its geographic distribution.

Diagnosis, incidence, and postoperative complications

At present, the main examinations for elastofibroma are ultrasonography, CT and MRI. Ultrasonography can show cord-like hyperechogenicity along the long axis of the elastofibroma lesion, but it still has certain limitations. CT can easily confuse tumour tissue with muscle tissue. MRI is more sensitive to adipose tissue in tumours and can show tumour structure more clearly; thus, MRI is the first choice of imaging modality for examination of elastofibromas. Due to the special location of the disease, the lesion can be evaluated better when the patient’s arms and body are bent forward at a 10–15-degree angle during physical examination. Careful physical examination is required before operation. For patients with unilateral disease, attention should be simultaneously paid to the opposite side. However, when the patient has bilateral onset and when the lesions on both sides are similar in size and symmetrical in shape, they are easily mistaken for normal muscle structures and can be missed. Therefore, correct understanding of the imaging features of this disease is the key for avoiding missed diagnosis or misdiagnoses. Therefore, we believe that conventional biopsy can differentiate benign cases from malignant cases, and if the tumour location and imaging manifestations are typical, biopsy before operation is not necessary.

A review of the oncology database of the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Birmingham, UK, showed that 15 (0.086%) of the 17,500 soft-tissue tumours detailed over the past 20 years were elastofibromas.23 Among the 12,577 soft-tissue tumours in Japan’s soft-tissue tumour registry database, 130 (1.0%) were elastofibromas;24 this value was significantly higher than that in the UK database. However, only a few recurrent cases have been reported in the literature.16,25,26 Among the 172,047 soft-tissue tumours recorded in our hospital from 2010 to 2018, 73 were elastofibromas, with an overall incidence of 0.04%. Compared with the aforementioned Japanese study, our data are consistent with the data from the UK registries and also reflect the rarity of the disease. In a series of clinical reports, the incidence of bilateral disease was between 12% and 73%.27 Coskun et al reported that the incidence of bilateral disease was about 10%.28 In our case series, the incidence of bilateral disease was 23% and, generally, the size of the right lesion was significantly larger than that of the left. All 90 lesions in our study were completely excised by surgery. The follow-up period ranged from one month to nine years, and no recurrence, malignant transformation or metastasis of the elastofibroma has been observed thus far.

The most common complication after resection of elastofibroma is wound effusion, which is caused by large size of the tumour body or insufficient fixation. There is no consensus in the literature on postoperative rehabilitation programmes. Surgeons should carefully observe postoperative wounds and apply negative pressure through drainage tubes to promote wound healing. Based on our experience, we recommend that the drainage tube be fixed for at least one week. Ultrasound-guided puncture or catheter drainage has a good therapeutic effect on patients with effusion. In this study, we used postoperative wound drainage, bandage compression and postoperative limb immobilisation to reduce the occurrence of haematoma. Recent studies have shown that the combined application of cotton thread sutures and fibrin sealant can reduce the incidence of hematoma following donor site operation.29

Conclusions

In summary, elastofibroma is a rare, benign, soft-tissue tumour that is common in elderly women. The inferior angles of the scapulae are the main site of this disease, with some cases presenting with bilateral symmetrical disease. Generally, the right lesion is slightly larger than the left lesion. Although elastofibroma can occur in other parts outside the subscapular region, if the lesion is located under the bilateral subscapular region and if the imaging findings are typical, it can be diagnosed as elastofibroma without puncture biopsy before operation; furthermore, short- and long-term outcomes following surgical treatment are good. Our study findings can be applied for developing standardised approaches for pathological examination and imaging studies to ensure timely and appropriate diagnosis of elastofibroma.

References

- 1.Jarvi O, Saxen E. Elastofibroma dorse. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl 1961; : 83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDM, Uni KM. Pathology and Genetics for Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors Volume 5 Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith HG, Hannay JA, Thway K et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: the clunking tumour that need not cause alarm. Ann R Coll Surg Eng 2016; : 208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortman KD, Hochheiser GM, Giblin EM et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: clinicopathologic review of 6 cases. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; : 1,894–1,897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majó J, Gracia I, Doncel A et al. Elastofibroma dorsi as a cause of shoulder pain or snapping scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; : 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lococo F, Cesario A, Mattei F et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: clinicopathological analysis of 71 cases. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; : 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freixinet J, Rodríguez P, Hussein M et al. Elastofibroma of the thoracic wall. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008; : 626–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapff PD, Hocken DB, Simpson RH. Elastofibroma of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987; : 468–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson FC, Norman1 LS, Truitt CA, Morgan MB. Elastofibroma of the foot: uncommon presentation: a case report and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int 2000; : 775–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darling MR, Kutalowski M, Macpherson DG et al. Oral elastofibromatous lesions: a review and case series. Head Neck Pathol 2011; : 254–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kastner M, Salai M, Fichman S et al. Elastofibroma at the scapular region. Isr Med Assoc J 2009; : 170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Nictolis M, Goteri G, Campanati G, Prat J. Elastofibrolipoma of the mediastinum: a previously undescribed benign tumor containing abnormal elastic fibers. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; : 364–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson B, Geneva I, Landas S et al. Novel association of elastofibroma with aortic stenosis: report of a case report interfering with a thoracotomy procedure and a reassessment of typical patient demographics and tumor location. J Thorac Oncol 2015; : e18–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumaratilake JS, Krishnan R, Lomax-Smith J, Cleary EG. Elastofibroma : disturbed elastic fibrillogenesis by periosteal-derived cells? An immunoelectron microscopic and in situ hybridization study. Hum Pathol 1991; : 1,017–1,029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akçam Tİ, Çağırıcı U, Çakan A, Akin H. Bilateral familial elastofibroma dorsi: is genetic abnormality essential? Ann Thorac Surg 2014; : e31–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamine N, Nohara Y, Ito E. Elastofibroma in Okinawa: a clinicopathologic study of 170 cases. Cancer 1982; : 1,794–1,805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernández JLG, Rodríguez-Parets JO, Valero JM et al. High-resolution genome-wide analysis of chromosomal alterations in elastofibroma. Virchows Archiv 2010; : 681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishio JN, Iwasaki H, Ohjimi Y et al. Gain of Xq detected by comparative genomic hybridization in elastofibroma. Int J Mol Med 2002; : 277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida C, Misaki N. Elastofibroma developing at the subscapular port site after thoracoscopic surgery: first case report. Surg Case Rep 2017; : 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faccioli N, Foti G, Comai A et al. MR imaging findings of elastofibroma dorsi in correlation with pathological features: our experience. Radiol Med 2009; : 1,283–1,291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daigeler A, Vogt PM, Busch K et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: differential diagnosis in chest wall tumours. World J Surg Oncol 2007; : 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin ML, Perzin KH, Markowitz AM. Elastofibroma dorsi: benign chest wall tumor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989; : 234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandrasekar CR, Grimer RJ, Carter SR et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: an uncommon benign pseudotumour. Sarcoma 2008; : 756565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagano S, Yokouchi M, Setoyama T et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: surgical indications and complications of a rare soft tissue tumor. Mol Clin Oncol 2014; : 421–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kransdorf MJ, Meis JM, Montgomery E. Elastofibroma: MR and CT appearance with radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; : 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mcgregor JC, Rao SS. Elastofibroma: a rare cause of painful shoulder. Br J Surg 2010; : 583–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minarro JC, Urbano-Luque MT, López-Jordan A et al. The comparison of measurement accuracy among three different imaging modalities in evaluating elastofibroma dorsi: an analysis of 52 cases. Int Orthop 2015; : 1,145–1,149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coskun A, Yildifim M. Bilateral elastofibroma dorsi. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; : 2,242–2,244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey SH, Oni G, Guevara R et al. Latissimus dorsi donor-site morbidity: the combination of quilting and fibrin sealant reduce length of drain placement and seroma rate. Ann Plast Surg 2012; : 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]