Abstract

Introduction

Anastomosis formation constitutes a critical aspect of many gastrointestinal procedures. Barbed suture materials have been adopted by some surgeons to assist in this task. This systematic review and meta-analysis compares the safety and efficacy of barbed suture material for anastomosis formation compared with standard suture materials.

Methods

An electronic search of Embase, Medline, Web of Science and Cochrane databases was performed. Weighted mean differences were calculated for effect size of barbed suture material compared with standard material on continuous variables and pooled odds ratios were calculated for discrete variables.

Findings

There were nine studies included. Barbed suture material was associated with a significant reduction in overall operative time (WMD: -12.87 (95% CI = -20.16 to -5.58) (P = 0.0005)) and anastomosis time (WMD: -4.28 (95% CI = -6.80 to -1.75) (P = 0.0009)). There was no difference in rates of anastomotic leak (POR: 1.24 (95% CI = 0.89 to 1.71) (P = 0.19)), anastomotic bleeding (POR: 0.80 (95% CI = 0.29 to 2.16) (P = 0.41)), or anastomotic stricture (POR: 0.72 (95% CI = 0.21 to 2.41) (P = 0.59)).

Conclusions

Use of barbed sutures for gastrointestinal anastomosis appears to be associated with shorter overall operative times. There was no difference in rates of complications (including anastomotic leak, bleeding or stricture) compared with standard suture materials.

Keywords: Barbed suture; Anastomosis, Roux en-y; Gastric bypass; Colorectal surgery

Introduction

Gastrointestinal anastomosis forms a critical step during many minimally invasive surgical procedures related to bariatric surgery, oesophagogastric surgery and colorectal surgery. Many surgeons perform these anastomoses via a stapled technique (using either a linear or circular stapling device).1 This requires closure of the remaining enterotomy, which during bariatric surgical procedures is most often performed via laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing, with this technique also employed by some colorectal surgeons.2 Some surgeons may also perform a fully handsewn method of laparoscopic anastomosis.3–5 In either situation, laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing is considered one of the most challenging and time-consuming parts of this type of surgery.

Barbed suture materials have been used in orthopaedic,6 gynaecological,7,8 urological,9 and plastic surgery.10 These suture materials have been adopted by some gastrointestinal surgeons for anastomosis formation as they have the advantage of not requiring laparoscopic knot-tying and they remove the potential of the suture to slip during continuous laparoscopic suturing.11

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to establish the potential benefits of barbed suture materials for anastomosis formation compared with standard suture materials in terms of operative time and patient outcomes (including anastomotic leak rates, incidence of anastomotic bleeding and anastomotic stricture).

Methods

Literature search strategy

An electronic literature search was undertaken using Embase, Medline and Web of Science databases. The search terms ‘barbed suture’, ‘enterotomy’, ‘anastomosis’, ‘gastrointestinal’ and medical subject headings ‘bariatric surgery’, ‘gastric bypass’, ‘gastrectomy’ ‘colorectal surgery’ were used in combination with the Boolean operators AND or OR. Two authors (TW and MSM) performed the literature search in January 2019. The reference lists of articles obtained were also searched to identify further relevant citations. Abstracts of the articles identified by the electronic search were scrutinised by two authors (TW and MSM) to determine their suitability for inclusion in the pooled analysis.

Publications were included if they were comparative studies investigating the use of barbed suture materials for gastrointestinal anastomosis formation compared with an appropriate control group who underwent anastomosis formation using a standard suture-type.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were overall operative time and anastomosis time. Secondary outcome measures were rates of overall morbidity, anastomotic leak, anastomotic bleeding and anastomotic stricture, as well as overall hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

Data from eligible trials were entered into a computer spreadsheet for analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using StatsDirect version 2.5.7. Weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated for the effect size of barbed suture materials upon continuous variables. Pooled odds ratios (POR) were calculated for the effect of the use of barbed sutures on discrete variables. All pooled outcome measures were determined using random effects models.12 Heterogeneity among trials was assessed by means of the Cochran’s Q statistic, a null hypothesis in which P less than 0.05 is taken to indicate the presence of significant heterogeneity.13 The Egger test was used to assess the funnel plot for significant asymmetry, indication of possible publication or other biases.

Findings

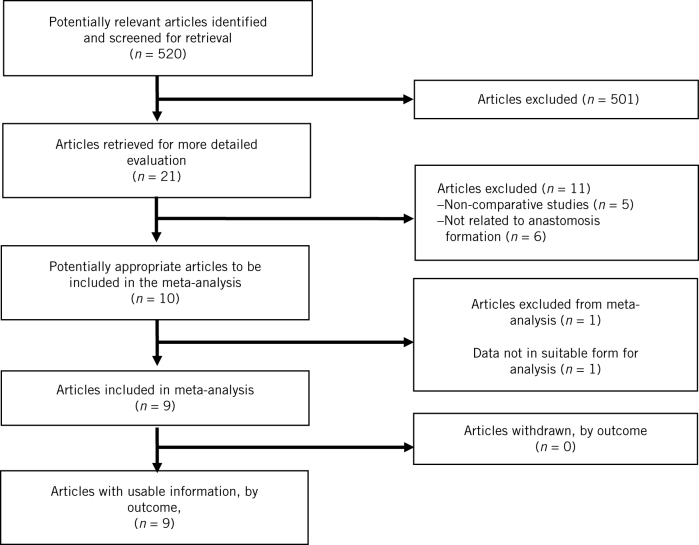

The literature search identified nine studies that were suitable for inclusion in the analysis (two randomised trials,14,15 six cohort studies,16–21 and one population based cohort study.22) Figure 1 demonstrates the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flowchart for the literature search. In total there were 26,475 patients included in the analysis, with 3031 patients in the barbed suture group and 23,444 in the standard suture material group. Seven studies investigated gastric bypass for obesity,14–19,22 and two studies investigated colorectal anastomosis.20,21 Table 1 provides details of patient demographics for each individual study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart with details of literature search.

Table 1.

Patient demographic details from all studies.

| Study | Procedure type | Patients (n) | Age (years) | Female gender, n (%) | Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | ||

| Bracale20 | Colorectal | 40 | 40 | 74.1 ± 9.9 | 72.5 ± 11.2 | 17 (43) | 12 (30) | 30.6 ± 7.5 | 30 ± 7.9 |

| Costantino16 | LRYGB | 76 | 219 | 40 ± 10.7 | 38 ± 10.8 | 63 (83) | 213 (97) | 44 ± 6.5 | 44.9 ± 6.9 |

| De Blasi17 | LRYGB | 50 | 50 | 42.4 ± 10.6 | 43.7 ± 12.1 | – | – | 44.7 ± 7.6 | 44.0 ± 4.5 |

| Feroci21 | Colorectal | 47 | 47 | 69 (43–94) | 72.5 (52–87) | 22 (47) | 27 (57) | 24.20 (20–29) | 25 (18–30) |

| Gys14 | LRYGB | 100 | 100 | 38.9 | 40.4 | F : M ratio 2.8 | F : M ratio 4.0 | 40.8 | 40.5 |

| Milone15 | SAGB | 30 | 30 | 35.1 ± 9.3 | 36.5 ± 6.8 | 9 (30) | 12 (40) | 46.4 ± 3.3 | 45.8 ± 3.5 |

| Pennestri:18 | |||||||||

| LRYGB | LRYGB | 244 | 244 | 42 (35–49) | 43 (35–50) | 179 (73) | 182 (74) | 43.3 (40.3–47.3) | 43.8 (40.5–47.4) |

| SAGB | SAGB | 24 | 24 | 42 (35.25–47.75) | 46 (25.25–53.50) | 17 (70.8) | 16 (67) | 45.8 (42.1–50.7) | 49.3 (42.3–52.2) |

| Tyner19 | LRYGB | 38 | 46 | 46.3 ± 9.8 | 48.3 ± 11.9 | 35 (89.5) | 41 (89.1) | 41.3 ± 4.7 | 41.9 ± 5.3 |

| Vidarsson22 | LRYGB | 22795 | 2211 | 40.9 ± 11.2 | 41.0 ± 11.6 | 17142 (75) | 1694 (77) | 42.3 ± 5.2 | 41.3 ± 5.1 |

F, female; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass; M, male; SAGB, single anastomosis gastric bypass.

Quality assessment of studies was undertaken using the Jadad score for randomised studies and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for non-randomised studies23,24. Details of quality assessment are provided in Supplementary Table 1 (online only).

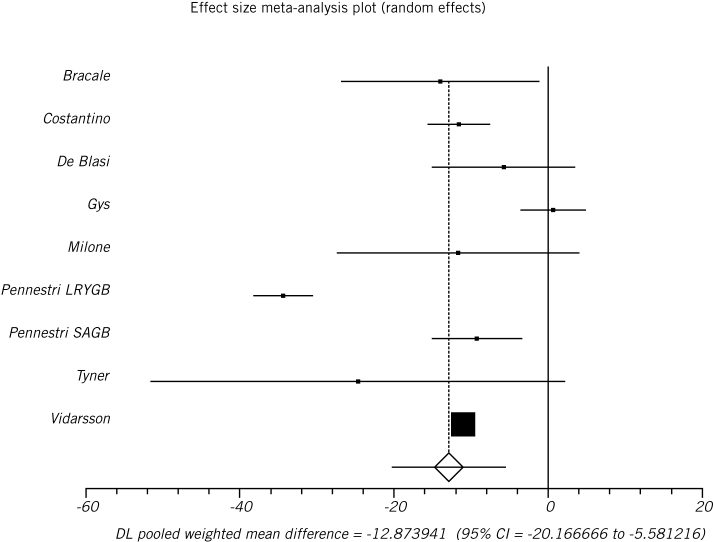

Operative time

Overall operative time was reported by eight studies.14–20,22 Use of barbed suture material for anastomosis formation was associated with a significant reduction in overall operative time compared to standard suture materials (WMD –12.87, 95% confidence interval, CI, –20.16 to –5.58, P = 0.0005; Figure 2). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 173.5; P < 0.0001; I2=95.4%) but no evidence of bias (Egger –0.53; P = 0.84; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Barbed suture material was associated with a significant reduction in overall operative time (weighted mean difference –12.87, 95% confidence interval –20.16 to –5.58, P = 0.0005).

Table 2.

Details of operative time and hospital stay from all studies.

| Study | Overall operative time (minutes) | GJ anastomosis time (minutes) | JJ anastomosis time (minutes) | Colorectal anastomosis time (minutes) | Hospital stay (days) | |||||

| Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | |

| Bracale20 | 134.9 ± 34.1 | 120.9 ± 23.2 | – | – | – | – | 17.5 ± 2.2 | 12.1 ± 2.3 | 5.1 ± 2.6 | 4.9 ± 2.1 |

| Costantino16 | 74.3 ± 15.3 | 62.7 ± 15.5 | 21.3 ± 6.3 | 17.4 ± 5.1 | 21.4 ± 4.9 | 15.2 ± 5.5 | – | – | – | – |

| De Blasi17 | 125.06 ± 20.32 | 119.28 ± 26.29 | 11 ± 1.55 | 8.22 ± 2.1 | – | – | – | – | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.45 |

| Feroci21 | 127.5a | 120a | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 (3–43) | 6 (3–70) |

| Gys14 | 60.73 ± 12.45 | 61.37 ± 17.48 | 8.26 ± 1.48 | 7.68 ± 1.18 | 6.17 ± 1.31 | 6.2 ± 0.98 | – | – | 3 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.2 |

| Milone15 | 134.4 ± 30.8 | 122.7 ± 31.1 | 24.1 ± 2.2 | 12.8 ± 1.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pennestri:18 | ||||||||||

| LRYGB | 95 (79.25–120) | 61.50(50–78.75) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 (4–6) | 3 (3–4) |

| SAGB | 76.5 (66–103.5) | 70 (51–94.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| Tyner19 | 178.9 ± 44.4 | 154.2 ± 74.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 1.4 |

| Vidarsson22 | 69 ± 33 | 58 ± 22 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.9 ± 2.6 | 1.5 ± 2.8 |

a Standard deviation not provided, therefore not included in meta-analysis.

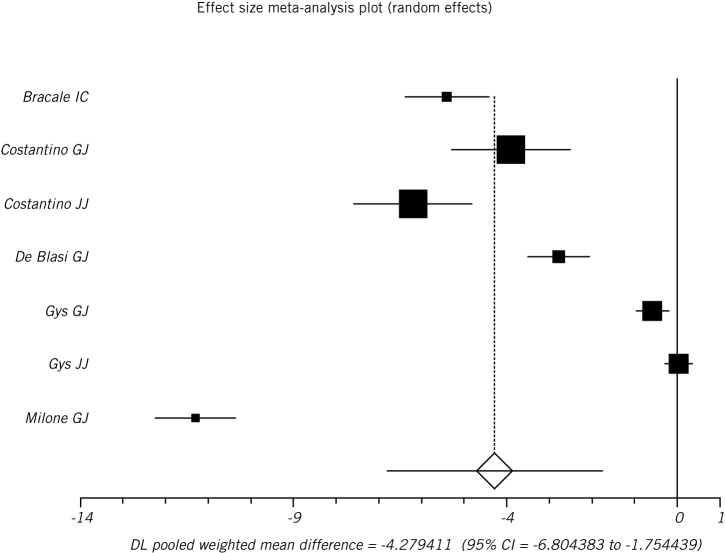

Five studies reported anastomosis time (one ileocolic anastomosis, four gastrojejunal anastomosis time, and two jejunojejunal anastomosis time).14–17,20 Barbed suture materials were associated with a significant reduction in anastomosis time (WMD –4.28, 95% CI –6.80 to –1.75, P = 0.0009; Figure 3). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q=665.9; P < 0.0001; I2 99.1%) and some evidence of bias (Egger –15.4; P = 0.02; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Barbed suture material was associated with a significant reduction in anastomosis time (weighted mean difference –4.28, 95% confidence interval –6.80 to –1.75, P = 0.0009).

Within bariatric surgery studies use of barbed suture material for gastrojejunal formation was associated with a significant reduction in anastomosis time (WMD –4.63, 95% CI –9.21 to –0.05, P = 0.047.14–17 There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 445.55, P < 0.0001, I2=99.3) but no evidence of bias (Egger –16.73, P = 0.28). For jejunojejunal anastomosis there was no significant difference in anastomosis time for barbed and regular suture material groups (WMD –3.05, 95% CI –9.15 to 3.05, P = 0.33).14,16 There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 82.71, P < 0.0001) and too few strata to assess for bias (Table 2).

Overall morbidity

Five studies provided details of overall morbidity.16,18–21 There was no significant difference in overall morbidity between the groups (POR 0.84, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.36, P = 0.49). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 4.89, P = 0.42, I2 0%) and no evidence of bias (Egger –0.12, P = 0.93; Table 3).

Table 3.

Details of complications from all studies.

| Author | Overall morbidity n (%) | Anastomotic leak n (%) | Anastomotic bleeding n (%) | Anastomotic stricture n (%) | ||||

| Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | Standard suture | Barbed suture | |

| Bracale20 | 19 (48) | 18 (45) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | – | – |

| Costantino16 | 2 (3) | 19 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| De Blasi17 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feroci21 | 10 (21) | 5 (11) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | – | – | – | – |

| Gys14 | – | – | 0 | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 | – | – |

| Milone15 | – | – | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pennestri:18 | ||||||||

| LRYGB | 9 (4) | 8 (3) | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| SAGB | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tyner19 | 7 (18) | 6 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vidarsson22 | – | – | 319 (1.4) | 39 (1.8) | – | – | 32 (0.17) | 2 (0.13) |

Anastomotic leak

All nine studies reported on incidence of anastomotic leakage, with only six studies having any cases of anastomotic leakage during their series.14,15,18,20–22 There was no difference in the rates of anastomotic leakage between the barbed suture and regular suture material groups (POR 1.24, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.71, P = 0.20). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 1.78, P = 0.88, I2 0%) and no evidence of bias (Egger –0.25, P = 0.47; Table 3).

Anastomotic bleeding

Rates of anastomotic bleeding were reported by seven studies,14–20 with five studies reporting cases of this complication.14–16,18,20 There was no difference in the rates of anastomotic bleeding between the groups (POR 0.80, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.16, P = 0.66). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 3.52, P = 0.62, I2 0%) and no evidence of bias (Egger –2.18, P = 0.07; Table 3).

Anastomotic stricture

Six studies reported the incidence of anastomotic stricture,15–19,22 with only two studies reporting cases of this complication.16,22 There were no differences in rates of anastomotic stricture between the two groups (POR 0.72, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.41, P = 0.59). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 0.08, P = 0.77) and too few strata to assess for bias (Table 3).

Hospital stay

Seven studies reported length of hospital stay.14,17–22 There was no difference in length of hospital stay between the two groups (WMD –0.54, 95% CI –1.28 to 0.20, P = 0.15). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Cochran Q 1807.4, P < 0.0001, I2 99.6%) but no evidence of bias (Egger –2.58, P = 0.78; Table 2).

Discussion

The pooled analysis of data from 26,475 patients has suggested that the use of barbed suture materials in gastrointestinal anastomosis is safe with an equivalent complication profile compared with standard suture materials. Barbed suture materials appear to carry the additional advantage of reduced overall operative times (WMD –12.87, 95% CI –20.16 to –5.58, P = 0.0005) and reduced anastomosis times (WMD –4.28, 95% CI –6.80 to –1.75, P = 0.0009). Within studies investigating bariatric surgery, this reduction in operative time appears to be particularly related to gastrojejunal anastomosis (WMD –4.63, 95% CI –9.21 to –0.05, P = 0.047), whereas there was no significant difference in time required for jejunojejunal anastomosis (WMD –3.05, 95% CI –9.15 to 3.05, P = 0.33). This adds additional insight into the potential benefits of barbed suture use during gastric bypass surgery beyond those identified in another recent meta-analysis which also included data from patients undergoing other forms of bariatric surgery (in particular use of barbed suture materials for reinforcement of staple lines during sleeve gastrectomy) and did not specifically examine differences in operative time for gastrojejunal and jejunojejunal anastomoses.25

These results indicate that the benefits of this form of barbed suture material are particularly evident during more complex tasks such as the formation of a gastrojejunal anastomosis, which is widely considered to be the most technically challenging section of a laparoscopic gastric bypass. Barbed suture materials can assist surgeons during anastomosis formation as their use can help to standardise the method of anastomosis by removing the need for intracorporeal knot tying and can make it unnecessary to maintain constant tension upon the thread during a running suture.26 Although barbed sutures may assist the surgeon during these tasks, it is important that care is still taken to ensure that the first placement of the suture is secured effectively and that each subsequent throw is laid down securely following each passage, as these suture materials do not necessarily ‘run through’ easily following multiple passages. Therefore, although barbed sutures can assist surgeons with closure of enterotomy during laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery, intracorporeal suturing remains a technically challenging aspect of these procedures where careful surgical technique is critical.

Previous in-vivo animal based-studies have demonstrated equivalent burst pressures for stomach and small bowel enterotomies that have been closed with a barbed suture or standard suture materials.27,28 This demonstrates the technical strength of this form of enterotomy closure and in clinical practice integrity of the gastrojejunal anastomosis can be tested by pressure to decrease complications.

One aspect that may have prevented the widespread adoption of barbed suture materials during laparoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis has been a perceived increased cost of the individual suture materials. Within the setting of orthopaedic surgery it has been demonstrated that usage of barbed suture materials for wound closure lead to an overall cost saving, largely as a result of reduced operative times compared with interrupted sutures.29 Two of the studies included within the current analysis were able to demonstrate reduced material costs when using a barbed suture material in a continuous method compared with interrupted stitches using standard suture materials.15,17 One study also hypothesised that the potential reduction in operating theatre time would reduce the overall costs of each procedure by approximately US$200,22 which would easily offset the additional costs of the barbed suture material.

Limitations of the current analysis include the fact that only two of the included studies were randomised.14,15 The remaining studies were non-randomised comparative studies with some comparing patients treated within separate time periods. This may have raised the potential for other unmeasured factors to influence outcomes, such as operative time. In all studies that compared data from separate time periods, patients included in the barbed suture material group underwent surgery in the later time period and therefore it is possible that operative times may have also been reduced as surgeon’s progressed through the proficiency gain curve for this procedure. There were limited data regarding outcomes for jejunojejunal and colorectal anastomosis. Although there was no significant difference in operative time for jejunojejunal anastomosis, only two studies reported operating times for this stage of the procedure.14,16 Additional data are needed to definitively establish if the use of barbed sutures may reduce time necessary for this stage of a gastric bypass procedure. Further studies are also required regarding barbed suture use in colorectal surgery, although intracorporeal suturing is less commonly undertaken in this form of surgery.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis has demonstrated that the use of barbed suture materials for gastrointestinal anastomosis formation is safe, with an equivalent rate of significant complications compared with standard suture materials. Use of barbed suture materials is associated with a significant reduction in overall operative time and time for anastomosis formation. Reductions in operative time may help to offset the additional costs of the suture material itself and may lead to further cost savings.

References

- 1.Edholm D, Sundbom M. Comparison between circular- and linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a cohort from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; : 1,233–1,236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleary RK, Kassir A, Johnson CS et al. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis for minimally invasive right colectomy: a multi-center propensity score-matched comparison of outcomes. PLoS One 2018; : e0206277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang H-P, Lin L-L, Jiang X, Qiao H-Q. Meta-analysis of hand-sewn versus mechanical gastrojejunal anastomosis during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Int J Surg 2016; : 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awad S, Aguilo R, Agrawal S, Ahmed J. Outcomes of linear-stapled versus hand-sewn gastrojejunal anastomosis in laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2015; : 2,278–2,283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendewald FP, Choi JN, Blythe LS et al. Comparison of hand-sewn, linear-stapled, and circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2011; : 1,671–1,675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han Y, Yang W, Pan J et al. The efficacy and safety of knotless barbed sutures in total joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018; : 1,335–1,345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peleg D, Ahmad RS, Warsof SL et al. A randomized clinical trial of knotless barbed suture vs conventional suture for closure of the uterine incision at cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; : 343.e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardella B, Dominoni M, Iacobone AD et al. What Is the role of barbed suture in laparoscopic myomectomy? A meta-analysis and pregnancy outcome evaluation. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2018; : 521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertolo R, Campi R, Klatte T et al. Suture techniques during laparoscopic and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of peri-operative outcomes. BJU Int 2018; : 923–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motosko CC, Zakhem GA, Saadeh PB, Hazen A. The implications of barbed sutures on scar aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018; : 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanc P, Lointier P, Breton C et al. The hand-sewn anastomosis with an absorbable bidirectional monofilament barbed suture Stratafix® during laparoscopic one anastomosis loop gastric bypass: retrospective study in 50 patients. Obes Surg 2015; : 2,457–2,460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; : 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; : 1,539–1,558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gys B, Gys T, Lafullarde T. The use of unidirectional knotless barbed suture for enterotomy closure in Roux-en-y gastric bypass: a randomized comparative study. Obes Surg 2017; : 2,159–2,163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milone M, Nicola M, Di D et al. Safety and efficacy of barbed suture for gastrointestinal suture: a prospective and randomized study on obese patients undergoing gastric bypass. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 2013; : 756–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costantino F, Dente M, Keller P. Barbed unidirectional V-Loc 180 suture in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a study comparing unidirectional barbed monofilament and multifilament absorbable suture. Surg Endosc 2013; : 3,846–3,851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blasi V De, Facy O, Goergen M et al. Barbed versus usual suture for closure of the gastrojejunal anastomosis in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a comparative trial. Obes Surg 2013; : 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennestrì F, Gallucci P, Prioli F et al. Barbed vs conventional sutures in bariatric surgery: a propensity score analysis from a high-volume center. Updates Surg 2019; : 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyner RP, Clifton GT, Fenton SJ. Hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy using knotless unidirectional barbed absorbable suture during laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2013; : 1,360–1,366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bracale U, Merola G, Cabras F et al. The use of barbed suture for intracorporeal mechanical anastomosis during a totally laparoscopic right colectomy: is it safe? A retrospective nonrandomized comparative multicenter study. Surg Innov 2018; : 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feroci F, Giani I, Baraghini M et al. Barbed versus traditional suture for enterotomy closure after laparoscopic right colectomy with intracorporeal mechanical anastomosis: a case–control study. Updates Surg 2018; : 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidarsson B, Sundbom M, Edholm D. Shorter overall operative time when barbed suture is used in primary laparoscopic gastric bypass: a cohort study of 25,006 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017; : 1,484–1,488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; : 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (cited July 2019).

- 25.Lin Y, Long Y, Lai S et al. The effectiveness and safety of barbed sutures in the bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2019; : 1756–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Facy O, De Blasi V, Goergen M et al. Laparoscopic gastrointestinal anastomoses using knotless barbed sutures are safe and reproducible: a single-center experience with 201 patients. Surg Endosc 2013; : 3,841–3,845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehrhart NP, Kaminskaya K, Miller JA et al. In vivo assessment of absorbable knotless barbed suture for single layer gastrotomy and enterotomy closure. Vet Surg 2013; : 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omotosho P, Yurcisin B, Ceppa E et al. In vivo assessment of an absorbable and nonabsorbable knotless barbed suture for laparoscopic single-layer enterotomy closure: a clinical and biomechanical comparison against nonbarbed suture. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 2011; : 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elmallah RK, Khlopas A, Faour M et al. Economic evaluation of different suture closure methods: barbed versus traditional interrupted sutures. Ann Transl Med 2017; ): S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]