Abstract

Three shape‐persistent [4+4] imine cages with truncated tetrahedral geometry with different window sizes were studied as hosts for the encapsulation of tetra‐n‐alkylammonium salts of various bulkiness. In various solvents the cages behave differently. For instance, in dichloromethane the cage with smallest window size takes up NEt4 + but not NMe4 +, which is in contrast to the two cages with larger windows hosting both ions. To find out the reason for this, kinetic experiments were carried out to determine the velocity of uptake but also to deduce the activation barriers for these processes. To support the experimental results, calculations for the guest uptakes have been performed by molecular mechanics’ simulations. Finally, the complexation of pharmaceutical interested compounds, such as acetylcholine, muscarine or denatonium have been determined by NMR experiments.

Keywords: imines, shape-persistent organic cages, host–guest chemistry, molecular mechanics

In the cage: [4+4] imine cages with various dimensions of window apertures have been studied in the uptake of ammonium ions of different sizes to get an insight into the uptake mechanism. Counterintuitively, the cage with the narrowest window‐size picks up the larger cation NEt4 +, but not the smaller NMe4 +.Thermodynamic as well as kinetic data were experimentally determined and in combination with theoretical studies used to propose uptake mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Supramolecular chemistry as we know it today goes back to the findings of Pedersen of crown ethers and their selective binding of alkali metal cations depending on ring size.1 Inspired by these findings, Jean‐Marie Lehn and coworkers designed three‐dimensional congeners of crown‐ethers; the macrobicyclic cryptands, accompanied by a significant increase of association constants and selectivities towards the alkaline metals.2 Later, larger host molecules or supramolecular capsules were developed to accommodate larger guests or molecular cations to generate fundamental knowledge or mimic biochemical recognition events.3 Still, more 50 years after the seminal papers of Pedersen were published, cation binding recognition events are still appealing, e. g. to template dynamically formed ortho‐ester4 or as stabilized reaction intermediates within the confined space of cages or capsules to accelerate chemical reactions.5 The larger the host molecules are, the more difficult their synthesis get.6 Often, multiple steps are required resulting in low overall yields.7 By the introduction of dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC),8 shape‐persistent organic cages become more readily available in a few steps, often with high yields in the multiple bond forming reaction to the cages due to the reversible nature of the bond formation.7b, 9 A large number of various cage sizes and geometries have meanwhile been realized by DCC,9b, 10 such as tetrahedra,11 prisms,12 cubes,13 adamantoids,14 and others.15 Even larger cages with diameters of three and more nanometers were reported.16

Besides the gain to fundamental understanding of cage formations,17 one of the main aspects was the investigation of gas sorption by porous organic cages.9b, 13c, 18 Despite early investigations of binding guest molecules inside the cavities of shape‐persistent organic cages,15a there has not too much been done in this respect in recent years,19 which is in contrast to the large number and variety of studied host‐guest complexes based on e. g. hydrogen bonding capsules20 or coordination cages.21 For instance, Cooper et al. used smaller tetrahedral imine cages with narrow windows to selectively separate isomeric mixtures of alkylated benzenes,22 or more recently, to separate H2 from D2.23 The same cages were used as stationary phases on columns to separate various analyte mixtures.

Here we present our studies of host‐guest binding of ammonium ions by shape‐persistent [4+4] imine cages with a truncated tetrahedral geometry.24 The three investigated [4+4] imine cages are structurally related and differ mainly in the window sizes, which are adjusted by various long substituents on the used 1,3,5‐triformylbenzene.24

2. Results and Discussion

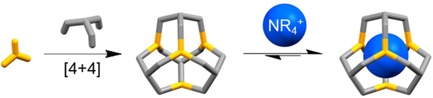

The truncated [4+4] imine cages were synthesized by reacting the conformationally fixed triethyltriamine 1 25 with the corresponding trialdehydes 2 a–c in a 1 : 1 stoichiometry in acetonitrile at room temperature (Scheme 1).24 Here the missing link, cage 3‐Me was synthesized and isolated in 37 % yield, which is in between the prior reported yields of 27 % (3‐H) and 46 % (3‐Et).24

Scheme 1.

[4+4]‐condensation of trimethylamine 1 and trisaldehydes 2 a–c. R=H, Me, Et.

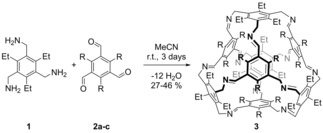

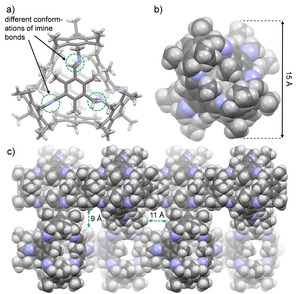

3‐Me was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy and MALDI MS (m/z=1599.0816 [M+H]+). By DOSY experiments in CD2Cl2 (T=298 K) a diffusion coefficient of D=6.6 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1 was measured, corresponding to a solvodynamic radius of rs=0.8 nm. These values are between the one of 3‐H (D=6.9 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1, r s=0.8 nm) and 3‐Et (D=4.5 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1, r s=1.2 nm) and fits to the estimated molecular dimension (d=1.5 nm) according to the data from single crystal X‐ray diffraction (Figure 1b). Single crystals of cage 3‐Me were grown from dichloromethane (Figure 1). The compound crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group A ma2 (Z=4) forming channels between the cage molecules with diameters of 9 Å ×11 Å, respectively (Figure 1c). The outer diameter of cage 3‐Me is with 1.5 nm nearly the same as found for cages 3‐H (1.6 nm) and 3‐Et (1.6 nm).24 It is worth mentioning that in contrast to the structures of cages 3‐H and 3‐Et the imine bonds are found to exist in various conformations (Figure 1a). Some are nearly orthogonal to the aromatic π‐planes with the imine protons pointing inside the cavity and other imine units are nearly coplanar to the aromatic ring, stabilized by conjugation. The space filling model of 3‐Me cage reveal a relative closed character (Figure 1b) with narrow windows for molecules accessing the inner cavity. To estimate the volume and window sizes of the cages 3‐H, 3‐Me and 3‐Et as potential hosts in solution, the preferred conformations and corresponding cavity volumes of these three cages were determined by DFT calculations (B3LYP, 6‐31G) with DCM as solvent (Figure 2a,b). The cross‐sections of the window sizes (distances between the atom centers of two closest carbon atoms) of the three cages decrease with the bulkiness of the substituents of the former trialdehyde linker (3‐Et: 7.1 ⋅ 3.4 Å=24.1 Å2; 3‐Me: 7.1 ⋅ 4.0 Å=28.4 Å2 and for 3‐H: 7.2 ⋅ 6.9 Å=49.7 Å2). The corresponding calculated cavity volumes (for a probe radius of 1.4 Å) follow the same trend (3‐H: 337 Å3, 3‐Me: 253 Å3 and 3‐Et: 218 Å3).

Figure 1.

Single‐crystal structure of 3‐Me. a) Capped stick model. b) Space‐filling model. c) Space‐filling model of the packing along the crystallographic b‐axis (1x1x2 unit cell).

Figure 2.

DFT calculated structures of the three cages 3‐H, 3‐Me and 3‐Et in DCM and the guests NMe4 +, NEt4 +, NPr4 + and NBu4 +. a) Window size; b) Illustration of the cavity volume computed with SwissPDBViewer.28 c) Volume of the guests.

Because we were interested in the uptake of ammonium ions, we also estimated the volumes of the homologous series of tetra‐n‐alkyl‐ammonium ions (Figure 2c), which is between 95 Å3 for the smallest guest NMe4 + and 304 Å3 for the biggest guest NBu4 +. Correlating the volumes of the host cavities with those of the ammonium ions as potential guests, the occupancies were estimated (Table 1).26 According to Rebek's “55 % rule”,27 it is expected that cage 3‐H should be able to take up NMe4 +, NEt4 + and even NPr4 + but not NBu4 +. Cage 3‐Me with a smaller cavity volume should be able to host NMe4 + and NEt4 + but not the two larger ones and 3‐Et should take up the smallest cation NMe4 + and maybe is able to host the next larger NEt4 +. For the latter the estimated occupancy is with 75 % borderline according to Rebek's rule.27a

Table 1.

Calculated occupancies of the space in the cavity by ammonium guests.

|

guest |

occupancy [%][a] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

3‐H |

3‐Me |

3‐Et |

|

|

NMe4 + |

28 |

38 |

44 |

|

NEt4 + |

48 |

64 |

75 |

|

NPr4 + |

70 |

93 |

108 |

|

NBu4 + |

90 |

120 |

139 |

[a] occupancy=V guest/V cavity

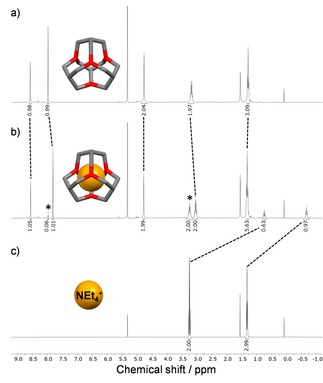

We started the complexation experiments with 3‐H as host and NEt4 + as guest in CD2Cl2 as solvent. As counter ion, the weekly coordinating anion BF4 − was chosen. After 18 hours the mixture was analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3b). To our delight the formed host guest complex shows a separate set of signals in the 1H NMR spectrum, with the resonances of one equivalent of encapsulated guest. The signal for the CH 2‐group of the encapsulated guest is shifted up‐field by Δδ=−2.5 ppm from δ=3.24 to 0.74 ppm, whilst the resonance of the CH3‐group is shifted by Δδ=−1.99 ppm from δ=1.32 to −0.67 ppm (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Representative 1H NMR spectra (CD2Cl2, 300 MHz) of the host guest experiments. a) 3‐H. b) Mixture of NEt4BF4 (3 eq.) and 3‐H, the shift of the signals for the host‐guest complex are highlighted with dotted lines. * residues of free 3‐H and of free NEt4BF4. c) NEt4BF4 without host.

Furthermore, DOSY NMR experiments confirm that encapsulated tetra‐n‐alkyl‐ammonium ions diffuse at the same rate as the host cages with a diffusion coefficient of D=7.1 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1 (r s=0.7 nm, see Supporting Information). After another 48 hours no further change of integral ratios was observed, suggesting that the system is in the thermodynamic equilibrium. Due to the slow exchange rate, compared to the NMR timescale, the association constant can be calculated by considering the mass balance law (for details, see Supporting Information). Equilibrium concentrations are taken by integration of characteristic signals of the host‐guest complex and those of free host and guest.29

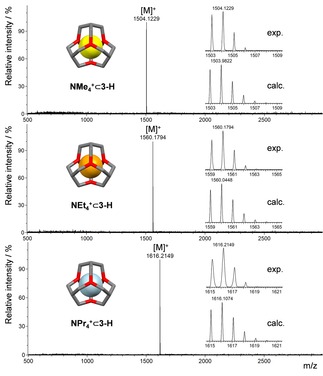

For NEt4 + ⊂3‐H an association constant of K a=2.4 ⋅ 103 M−1 was determined. As mentioned above, by comparison of the relative integrals of bound guest to bound host, a stoichiometry of 1 : 1 was obtained. This ratio was confirmed by MALDI‐TOF MS experiments (see Figure 4), were the singly charged ion was found (NEt4 + ⊂3‐H (m/z=1560.1794; calc. for C104H128N13 +=1560.0448). Next we investigated the complexation behavior for smaller and larger ammonium ions. NMe4 + is bound inside the cavity, but the association constant drops by two orders of magnitude to K a=1.9 ⋅ 101 M−1. For NPr4 + a higher association constant (K a=1.9 ⋅ 103 M−1) was found, with a comparable value as NEt4 + and for NBu4 + no binding was detected. Again, by MALDI‐TOF MS experiments only the singly charged ions were found (NMe4 + ⊂3‐H; m/z=1504.1229; calc. for C100H120N13 +=1503.9822) and NPr4 + ⊂3‐H (m/z=1616.2149; calc. for C108H136N13 +=1616.1074) suggesting a 1 : 1 host‐to‐guest ratio.

Figure 4.

MALDI‐TOF MS experiments of NMe4 + ⊂3‐H, NEt4 + ⊂3‐H and NPr4 + ⊂3‐H. Inlets: Comparison of calculated and measured m/z‐value.

The next potential host compound that was studied was cage 3‐Me with narrower windows. It is worth mentioning that in comparison to free 3‐H, the free 3‐Me shows a strong peak broadening in the 1H NMR spectrum when CD2Cl2 is used as solvent. Most likely this is due to slow solvent exchange on the NMR timescale. As soon as the cavity of the cage is blocked by a guest, sharp signals are observed again (see Supporting Information). As expected, 3‐Me binds NMe4 + (K a=4.7 ⋅ 101 M−1) and NEt4 + (K a>1 ⋅ 105 M−1).29 The larger guests NPr4 + and NBu4 + do not fit any more. In contrast to the other two cages, cage 3‐Et behaved a little bit differently than intuitively expected: It only takes up NEt4 + (K a >1 ⋅ 105 M−1) but not the smaller NMe4 +.

We studied the complexation behavior in other, less polar solvents (THF‐d8, toluene‐d8 and CDCl3) and only for 3‐H host‐guest complexation was observed. In THF‐d8 3‐H binds the whole series slightly stronger than in DCM (Figure 5). For NMe4 + an association constant of K a=2.1 ⋅ 101 M−1 was determined and for guests NEt4 + and NPr4 + again, the association constants are beyond K a >1 ⋅ 105 M−1. Most interestingly, in this solvent, even NBu4 + is picked up with a relatively large association constant of K a=2.1 ⋅ 103 M−1.

Figure 5.

Schematic summary of the size selectivity with association constants Ka [M−1] for the encapsulation in different solvents (for experimental details and standard deviations, see Supporting Information).

It is worth mentioning that the terminal protons of the propyl chains of NPr4 + are less up‐field shifted than the β‐protons of the chains (see Supporting Information), suggesting that the chains are “folded” in a manner that the resonance of the β‐protons is more influenced by the aromatic “wall” of the cages, which is in line with observations made before e. g. for capsules.30 The same effect, even more pronounced was detected with the butyl chains of NBu4 + accompanied by a significant peak broadening of the encapsulated guest signals. Rebek and co‐workers described in their work, that packing coefficients higher than 65 % lead to an artificial freezing of the guest in the cage, which is responsible for the peak broadening.27a This is in agreement with our observations, indicating a restricted movement of the cations in the cavity compared with the freedom it has in the solvent.

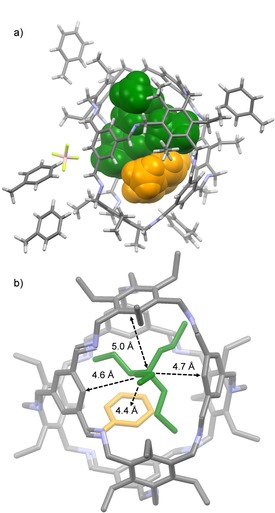

In toluene‐d8 basically the same trend is observed, although the bare ammonium salts are of low solubility herein. Again, even NBu4 + is complexed with K a=4.4 ⋅ 101 M−1. The binding of NBu4 + in these two solvents seem to be contradictive to the above discussed calculated occupancies in combination with Rebek's rule (see Table 1).27a However, from the complex NPr4 + ⊂3‐H we got a single crystal structure by X‐ray diffraction showing that the cavity is expandable in volume (458 Å3) (Figure 6a). Taking this volume now to calculate the occupancy for NBu4 + , one clearly is with 66 % below the limit according to Rebek's rule.27a The (NPr4 + ⋅toluene⊂3‐H)BF4 complex crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P 21/c (Z=4), with five molecules toluene outside the cage and one inside. The additional toluene molecule inside the cavity further stabilizes the guest by cation‐π interaction in a distance of 4.4 Å (Figure 6, b. Distance measured from π‐plane of aromatic ring to positively charged nitrogen). All alkyl chains of the guest point towards the windows. The counter ion BF4 − is located outside the cage cavity.

Figure 6.

Single‐crystal structure analysis of (NPr4 + ⋅toluene⊂3‐H)BF4. a) Stick model of Et‐H and space filling model of the guest toluene in orange and NPr4 + in green. b) Distances of nitrogen to center of the aromatic units.

In CDCl3, both NEt4 + and NPr4 + were bound with significantly larger association constants (K a>1 ⋅ 105 M−1) than in DCM. From previous work we know that cage 3‐H is not stable in CHCl3 and decomposes by time, most likely due to traces of hydrochloric acid.24 So it is in the case of NMe4 + and NBu4 + and decomposition is faster than complexation, making any assumption of association constants impossible.

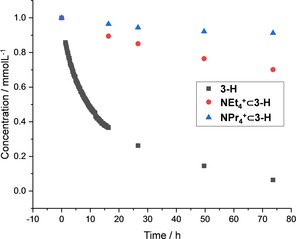

Contrary, in the case of NEt4 + and NPr4 + the decomposition is significantly lowered due to a stabilizing effect, which reminds one to e. g. the tobacco mosaic virus, keeping its tubular form only with the RNA encapsulated.31 The reaction rate of the decomposition could be slowed down by two orders of magnitude from k dec=1.6 ⋅ 10−5 s−1 (free 3‐H) to k dec=1.3 ⋅ 10−6 s−1 (NEt4 + ⊂3‐H) and k dec=3.3 ⋅ 10−7 s−1 for NPr4 + ⊂3‐H (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Concentration vs. time diagram of the decomposition of 3‐H in CDCl3, followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (300 MHz).

Comparisons of the host‐guest complexes with the ammonium salts by 19F‐NMR spectroscopy showed no significant shifted peak for the BF4‐counteranion, like it was found in other works.32 Furthermore, by 1H‐19F HOESY experiments no coupling of fluorine with any of the cage protons was found (see Supporting Information), suggesting that the anion is not bound inside the cavities. This is in agreement with the obtained crystal structure of the (NPr4 + ⋅toluene⊂3‐H)BF4 complex (see discussion above).

To further investigate the influence of the counter ion on the binding in 3‐H, 3‐Me and 3‐Et, tetra‐n‐alkyl‐ammonium iodides were studied in DCM. In contrast to the before used BF4 − salts the association constants dropped for all complexes (Table 2). NMe4 + is bound about three times less with cages 3‐H and 3‐Me (Ka=0.7 ⋅ 101 M−1 and 1.5 ⋅ 101 M−1), when the stronger coordinating iodide is present.33 As observed before, cage 3‐Et with the narrowest windows does not take up NMe4 + at all. NEt4 + is complexed by all three cages with significantly smaller association constants dropping several orders of magnitude, clearly revealing that separation of solvent‐shared ion pairs34 is negatively contributing to the overall Coulomb term of interaction. Similar observations were made before for other host systems.20g The smallest change has been observed for NPr4 +. Here, the association constant with 3‐H slightly decreases from K a=1.9 ⋅ 103 M−1 to K a=9.2 ⋅ 102 M−1.

Table 2.

Association constants [M−1] for the guest inclusion depending on the counter ion in DCM‐d2 (298 K).

|

Host |

NMe4 + |

NEt4 + |

NPr4 + |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BF4 − |

I− |

BF4 − |

I− |

BF4 − |

I− |

|

|

3‐H |

1.9 ⋅ 101 |

0.7 ⋅ 101 |

2.4 ⋅ 103 |

2.2 ⋅ 101 |

1.9 ⋅ 103 |

9.2 ⋅ 102 |

|

3‐Me |

4.7 ⋅ 101 |

1.5 ⋅ 101 |

>1 ⋅ 105 |

2.4 ⋅ 103 |

n. b. [a] |

n. b. [a] |

|

3‐Et |

n. b. [a] |

n. b. [a] |

>1 ⋅ 105 |

3.5 ⋅ 101 |

n. b. [a] |

n. b. [a] |

[a] n.b.=no binding was detected.

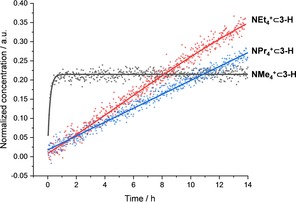

The kinetics of the uptake of tetra‐n‐alkyl‐ammonium cations in CD2Cl2 was followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy at 303 K for a solution 0.33 mM of cage 3‐H and 2.2‐3.3 mM of ammonium salt (see Supporting Information). The encapsulation of the smallest guest NMe4 + in 3‐H reaches equilibrium after only 25 minutes (k=6.4 ⋅ 10−2 M−1s−1; Figure 8). Whereas the reaction rates of the larger guests decrease about one order of magnitude with increasing size from 2.5 ⋅ 10−3 M−1s−1 (NEt4 +) to 1.9 ⋅ 10−3 M−1s−1 (NPr4 +). The complexation by 3‐Me and 3‐Et was very slow at 303 K, therefore, the kinetics were measured at 314 K. For the cage 3‐Me the rate for the guest uptake dropped by two orders of magnitude for NMe4 + (k=1.8 ⋅ 10−4 M−1s−1, 314 K) and to k=8.4 ⋅ 10−4 for M−1s−1 (NEt4 +, 314 K). For the 3‐Et with even more narrower window sizes the kinetics for complexation of NEt4 + revealed an encapsulation rate of k=6.1 ⋅ 10−5 M−1s−1 (314 K).

Figure 8.

Concentration vs. time diagram of the encapsulation of NMe4 +, NEt4 +, NPr4 + in 3‐H in CD2Cl2, followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (300 MHz, 303 K).

In principle two different mechanisms for the uptake of the ammonium salts are possible.35 One possibility is a gate‐opening mechanism where a reversible bond cleavage of one or multiple imine bonds occur to ‘open the lid’ of the cage to enable an encapsulation without or with low barrier of the guest ion, followed by reformation of the imine bonds to close the cage. Indeed, this mechanism has been proposed for an imine based hemicarcerand.36 The second possibility is a squeezing mechanism.37 Here, the cage stays intact and the guest is squeezed through the window into the cavity. In an extended study based on experimental observations and theoretical calculations, Raymond et al. concluded, that this mechanism is most likely the one tetrahedral metalcatecholate cages take up charged guests. Remarkably, even guests that are intuitively much too big, having to surpass a barrier of 251 kJ/mol, such as CoCp*2 +, seem to enter the cage without any ligand disassociation by this squeezing mechanism.

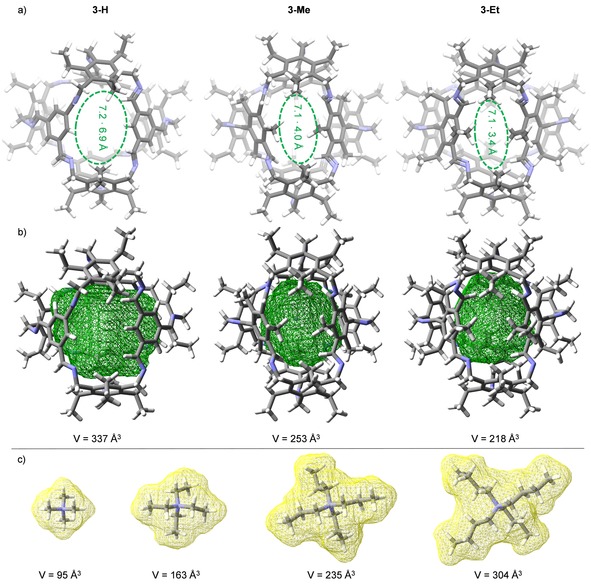

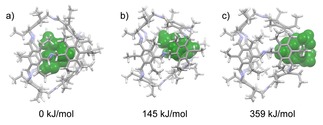

Considering the large differences in the kinetic uptake of ammonium ions of the same size by more than two orders of magnitude depending on the aperture of the cage windows in combination with similar it is assumed that a squeezing mechanism is more likely than a gate‐opening. Therefore, we performed force‐field based molecular dynamics simulations (MD) to study the mechanism of complexation behavior by a squeezing mechanism (for details, see Supporting Information). For each cage (3‐H, 3‐Me and 3‐Et) the dissociation of the two smaller ammonium ions NMe4 + and NEt4 + from the inner cavity through the windows without bond‐breaking were computed. For NMe4 + ⊂3‐H the barrier was with ΔG ǂ=61 kJ/mol approximately half that of NEt4 + ⊂3‐H (ΔG ǂ=141 kJ/mol). As soon as the window apertures get smaller, the calculated barriers increase significantly. For complex NMe4 + ⊂3‐Me and NEt4 + ⊂3‐Me the barriers are with ΔG ǂ=123 kJ/mol and ΔG ǂ=241 kJ/mol nearly double as for the complexes with cage 3‐H. Most interestingly, for the cage with the smallest windows (3‐Et) the calculated energies drop in comparison to the one with the medium sized windows (3‐Me) for the uptake of the smallest NMe4 + from ΔG ǂ=123 kJ/mol to ΔG ǂ=91 kJ/mol, whereas for the larger NEt4 + the barrier is with ΔG ǂ=359 kJ/mol very high and accompanied by a strong deformation of several bonds (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Computed conformations during the squeezing of NEt4 + through the window of 3‐Et in CD2Cl2. a) NEt4 + near the center of 3‐Et. b) NEt4 + approaching the window. c) strong deformation of 3‐Et at the transition state.

Since the energy is in the regime of covalent C−C bonds at least for the latter NEt4 + ⊂3‐Et a squeezing mechanism needs to be questioned. Further experiments and calculations need to be done. It is worth mentioning that various amounts of solvent molecules are found in the cavities as co‐guests within the thermodynamically most stable host‐guest complexes (see Supporting Information). The dynamics of the ammonium complexation for certain is influenced by the dynamics of these co‐complexed solvent molecules. Furthermore, not only the thermodynamics and the kinetics of the cation uptake by the cages play a role, but also the solvation of the ammonium salt in the solvent as well as the strip of the solvation sphere of the ammonium ions to enter the cage needs to be taken into account. The sum of all these energy contributions may explains, why the complexation of the smaller NMe4 + within cage 3‐Et is not observed, but the larger NEt4 + forms NEt4 + ⊂3‐Et. It is assumed that the lack of NMe4 + ⊂3‐Et is of thermodynamic reasons. However, this needs to be proved by further investigations.

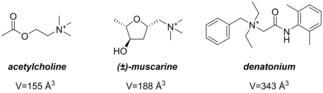

Finally, the pharmaceutically active ammonium salts acetylcholine chloride, its agonist (±)‐muscarine chloride and denatonium benzoate (Figure 10) were studied as potential guests. The sizes of acetylcholine (155 Å3) and (±)‐muscarine (188 Å3) differ only slightly and have approximately the size of NEt4 + (163 Å3). The denatonium cation is with 343 Å3 slightly larger than NBu4 + (304 Å3). The complexation studies were performed in a mixture of DCM‐d2 and acetonitrile‐d3 in a ratio of 9 : 1 (v/v).

Figure 10.

For host‐guest chemistry investigated pharmaceutically active ammonium cations with volumes.

Acetylcholine as well as (±)‐muscarine are bound by 3‐H and 3‐Me. For acetylcholine⊂3‐H an association constant of K a=8.3 ⋅ 101 M−1 was obtained, for (±)‐muscarine⊂3‐H a stronger binding was found (Ka=3.7 ⋅ 102 M−1). As expected from the previous experiments 3‐Me binds the two guest's acetylcholine and (±)‐muscarine stronger than 3‐H with K a=1.2 ⋅ 102 M−1 for acetylcholine⊂3‐Me and Ka=7.7 ⋅ 103 M−1 for (±)‐muscarine⊂3‐Me, respectively. Simultaneously the selectivity S = K a(muscarine)/ K a(acetylcholine) changes significant by altering the window size. 3‐Me binds (±)‐muscarine with S=64 more selectively than 3‐H with S=4.5. Denatonium as the biggest guest was not bound by any cage as well as 3‐Et also did not bound acetylcholine or (±)‐muscarine even after one week at 298 K (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association constants for the pharmaceutically active ammonia salts in DCM‐d2/acetonitrile‐d3 (ratio 9 : 1 (v/v)) at 298 K.

|

Host |

association constants K [M−1] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

acetylcholine+ |

(±)‐muscarine+ |

denatonium + |

|

|

3‐H |

8.3 ⋅ 101 |

3.7 ⋅ 102 |

n. b. [a] |

|

3‐Me |

1.2 ⋅ 102 |

7.7 ⋅ 103 |

n. b. [a] |

|

3‐Et |

n. b. [a] |

n. b. [a] |

n. b. [a] |

[a] n.b.=no binding was detected.

Conclusions

To summarize, the complexation of various tetralkylammonium salt ions of different sizes within structurally related [4+4]‐cages have been studied. The cages mainly differ in the size of the window apertures. By extended NMR studies, thermodynamic and kinetic data have been generated suggesting that the uptake of ammonium ions is most likely be favored by a squeezing mechanism rather than by a gate‐opening mechanism. This is also in line with the previous observation that the [4+4] cages are not thermodynamically but rather kinetically controlled products.24 Guest uptake mechanisms play a pivotal role for the usage of shape‐persistent organic cages as confined molecular reaction vessels and therefore more studies will be pursued to finally pin down the mechanism and use the [4+4] cages as vessels, e. g. for catalytic reactions with cationic transition states.5c, 21j, 21s, 38

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Funding of this project (CaTs N DOCs, grant no. 725765) by the ERC is highly acknowledged. Ziwei Pang acknowledges the China Scholarship Council for financial support.

J. C. Lauer, Z. Pang, P. Janßen, F. Rominger, T. Kirschbaum, M. Elstner, M. Mastalerz, ChemistryOpen 2020, 9, 183.

Dedicated to Professor Jean‐Marie Lehn on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Pedersen C. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 7017; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Pedersen C. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 7017–7036; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Pedersen C. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1988, 27, 1021–1027; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1988, 100, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Dietrich B., Lehn J. M., Sauvage J. P., Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 2885–2888; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Dietrich B., Lehn J. M., Sauvage J. P., Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 2889 ff; [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Lehn J. M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1988, 27, 89–112; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1988, 100, 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spath A., Konig B., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Brachvogel R.-C., Hampel F., von Delius M., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7129; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Shyshov O., Brachvogel R.-C., Bachmann T., Srikantharajah R., Segets D., Hampel F., Puchta R., von Delius M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 776–781; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 794–799; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Wang X., Shyshov O., Hanževački M., Jäger C. M., von Delius M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8868–8876; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Löw H., Mena-Osteritz E., von Delius M., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 11434–11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Zhang Q., Tiefenbacher K., Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 197–202; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Bräuer T. M., Zhang Q., Tiefenbacher K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7698–7701; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 7829–7832; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Catti L., Zhang Q., Tiefenbacher K., Synthesis 2016, 48, 313–328; [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Zhang Q., Catti L., Tiefenbacher K., Acc. Chem. 2018, 51, 2107–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murakami Y., Ohno T., Hayashida O., Hisaeda Y., Chem. Commun. 1991, 950–952. [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Kiggen W., Vögtle F., Angew. Chem. 1984, 96, 712–713; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1984, 23, 714–715; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Zhang G., Mastalerz M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1934–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Lehn J. M., Chem. Eur. J. 1999, 5, 2455–2463; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Rowan S. J., Cantrill S. J., Cousins G. R. L., Sanders J. K. M., Stoddart J. F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 898–952; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 938–993; [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Lehn J. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Mastalerz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5042–5053; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 5164–5175; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Mastalerz M., Acc. Chem. 2018, 51, 2411–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Rue N. M., Sun J., Warmuth R., Isr. J. Chem. 2011, 51, 743–768; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Acharyya K., Mukherjee P. S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8640–8653; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Santolini V., Miklitz M., Berardo E., Jelfs K. E., Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5280–5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Skowronek P., Gawronski J., Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4755–4758; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Elbert S. M., Regenauer N. I., Schindler D., Zhang W.-S., Rominger F., Schröder R. R., Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11438–11443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Schneider M. W., Oppel I. M., Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 4156–4160; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Acharyya K., Mukherjee P. S., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 1646–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Elbert S. M., Rominger F., Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 16707–16720; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Hong S., Rohman M. R., Jia J., Kim Y., Moon D., Kim Y., Ko Y. H., Lee E., Kim K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13241–13244; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13439–13442; [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Mukhopadhyay R. D., Kim Y., Koo J., Kim K., Acc. Chem. 2018, 51, 2730–2738; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Klotzbach S., Scherpf T., Beuerle F., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 12454–12457; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13e. Qu H., Wang Y., Li Z., Wang X., Fang H., Tian Z., Cao X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18142–18145; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13f. Xu D., Warmuth R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7520–7521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mastalerz M., Chem. Commun. 2008, 4756–4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Quan M. L. C., Cram D. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2754–2755; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Briggs M. E., Jelfs K. E., Chong S. Y., Lester C., Schmidtmann M., Adams D. J., Cooper A. I., Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 4993–5000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Liu X., Liu Y., Li G., Warmuth R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 901–904; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 915–918; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Zhang G., Presly O., White F., Oppel I. M., Mastalerz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1516–1520; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 1542–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Jelfs K. E., Eden E. G. B., Culshaw J. L., Shakespeare S., Pyzer-Knapp E. O., Thompson H. P. G., Bacsa J., Day G. M., Adams D. J., Cooper A. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9307–9310; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Greenaway R. L., Santolini V., Bennison M. J., Alston B. M., Pugh C. J., Little M. A., Miklitz M., Eden-Rump E. G. B., Clowes R., Shakil A., Cuthbertson H. J., Armstrong H., Briggs M. E., Jelfs K. E., Cooper A. I., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Hasell T., Cooper A. I., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16053; [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Beuerle F., Gole B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4850–4878; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 4942–4972; [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Mastalerz M., Synlett 2013, 24, 781–786; [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Mastalerz M., Schneider M. W., Oppel I. M., Presly O., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1046–1051; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 1078–1083; [Google Scholar]

- 18e. Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 10082–10091; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18f. Schneider M. W., Hauswald H.-J. S., Stoll R., Mastalerz M., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9861–9863; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18g. Avellaneda A., Valente P., Burgun A., Evans J. D., Markwell-Heys A. W., Rankine D., Nielsen D. J., Hill M. R., Sumby C. J., Doonan C. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3746–3749; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 3834–3837; [Google Scholar]

- 18h. Jin Y., Voss B. A., Noble R. D., Zhang W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6348–6351; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 6492–6495. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Davis A. P., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3629–3638; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Rios P., Carter T. S., Mooibroek T. J., Crump M. P., Lisbjerg M., Pittelkow M., Supekar N. T., Boons G.-J., Davis A. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3387–3392; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 3448–3453; [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Ríos P., Mooibroek T. J., Carter T. S., Williams C., Wilson M. R., Crump M. P., Davis A. P., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4056–4061; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19d. Tromans R. A., Carter T. S., Chabanne L., Crump M. P., Li H., Matlock J. V., Orchard M. G., Davis A. P., Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 52–56; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19e. Nishimura N., Yoza K., Kobayashi K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 777–790; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19f. Icli B., Sheepwash E., Riis-Johannessen T., Schenk K., Filinchuk Y., Scopelliti R., Severin K., Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1719–1721; [Google Scholar]

- 19g. Tamaki K., Ishigami A., Tanaka Y., Yamanaka M., Kobayashi K., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 13714–13722; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19h. Takahagi H., Fujibe S., Iwasawa N., Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 13327–13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. MacGillivray L. R., Atwood J. L., Nature 1997, 389, 469–472; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Gerkensmeier T., Iwanek W., Agena C., Frohlich R., Kotila S., Nather C., Mattay J., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 2257–2262; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Avram L., Cohen Y., Rebek J., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 5368–5375; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20d. Biros S. M., Rebek J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 93–104; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20e. Conn M. M., Rebek J., Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1647–1668; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20f. Zhang K. D., Ajami D., Rebek J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18064–18066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20g. Beaudoin D., Rominger F., Mastalerz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15599–15603; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 15828–15832. [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Sun Q. F., Iwasa J., Ogawa D., Ishido Y., Sato S., Ozeki T., Sei Y., Yamaguchi K., Fujita M., Science 2010, 328, 1144–1147; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Fujita D., Ueda Y., Sato S., Yokoyama H., Mizuno N., Kumasaka T., Fujita M., Chem-Us 2016, 1, 91–101; [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Tominaga M., Suzuki K., Kawano M., Kusukawa T., Ozeki T., Sakamoto S., Yamaguchi K., Fujita M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 5621–5625; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 5739–5743; [Google Scholar]

- 21d. Olenyuk B., Levin M. D., Whiteford J. A., Shield J. E., Stang P. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 10434–10435; [Google Scholar]

- 21e. Vardhan H., Mehta A., Nath I., Verpoort F., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 67011–67030; [Google Scholar]

- 21f. Ramsay W. J., Szczypinski F. T., Weissman H., Ronson T. K., Smulders M. M. J., Rybtchinski B., Nitschke J. R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5636–5640; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 5728–5732; [Google Scholar]

- 21g. Pasquale S., Sattin S., Escudero-Adan E. C., Martinez-Belmonte M., de Mendoza J., Nat. Commun. 2012, 3; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21h. Smulders M. M. J., Riddell I. A., Browne C., Nitschke J. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1728–1754; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21i. Han M., Engelhard D. M., Clever G. H., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1848–1860; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21j. Zarra S., Wood D. M., Roberts D. A., Nitschke J. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 419–432; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21k. Bloch W. M., Clever G. H., Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8506–8516; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21l. Castilla A. M., Ramsay W. J., Nitschke J. R., Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 256–263; [Google Scholar]

- 21m. Frank M., Johnstone M. D., Clever G. H., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14104–14125; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21n. Fiedler D., Pagliero D., Brumaghim J. L., Bergman R. G., Raymond K. N., Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 846–848; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21o. Brown C. J., Toste F. D., Bergman R. G., Raymond K. N., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3012–3035; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21p. Fiedler D., Bergman R. G., Raymond K. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6748–6751; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 6916–6919; [Google Scholar]

- 21q. Caulder D. L., Raymond K. N., Acc. Chem. 1999, 32, 975–982; [Google Scholar]

- 21r. Fiedler D., Bergman R. G., Raymond K. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 745–748; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 759–762; [Google Scholar]

- 21s. Fiedler D., Leung D. H., Bergman R. G., Raymond K. N., Acc. Chem. 2005, 38, 349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitra T., Jelfs K. E., Schmidtmann M., Ahmed A., Chong S. Y., Adams D. J., Cooper A. I., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu M., Zhang L., Little M. A., Kapil V., Ceriotti M., Yang S., Ding L., Holden D. L., Balderas-Xicohténcatl R., He D., Clowes R., Chong S. Y., Schütz G., Chen L., Hirscher M., Cooper A. I., Science 2019, 366, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lauer J. C., Zhang W. S., Rominger F., Schroder R. R., Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1816–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vacca A., Nativi C., Cacciarini M., Pergoli R., Roelens S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16456–16465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.For the calculation of the occupancies we did not take into account that attractive cation-π interactions between the host and guest may lead to a contraction of the cage and therefore cause higher occupancy ratios.

- 27.

- 27a. Mecozzi S., Rebek J., Chem. Eur. J. 1998, 4, 1016–1022; [Google Scholar]

- 27b.It should be noted that witihn the orginal paper of the so called Rebek′s 55 % rule a number of guest molecules occupied even more space (up to 80 %) and therefore the herein discussed findings fit well with the observations made and discussed in ref [27a].

- 28. Guex N., Peitsch M. C., Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thordarson P., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1305–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caulder D. L., Powers R. E., Parac T. N., Raymond K. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1840–1843; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1998, 110, 1940–1943. [Google Scholar]

- 31.

- 31a. Klug A., Philos T Roy Soc B 1999, 354, 531–535; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31b. Namba K., Stubbs G., Science 1986, 231, 1401–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paul R. L., Bell Z. R., Fleming J. S., Jeffery J. C., McCleverty J. A., Ward M. D., Heteroat. Chem. 2002, 13, 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krossing I., Raabe I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2066–2090; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 2116–2142. [Google Scholar]

- 34.

- 34a. Grunwald E., Anal. Chem. 1954, 26, 1696–1701; [Google Scholar]

- 34b. Sadek H., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 301–306; [Google Scholar]

- 34c. Sacks F. M., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 5172–5175; [Google Scholar]

- 34d. Miller R. C., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 3076–3080; [Google Scholar]

- 34e. Sadek H., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 5905–5909; [Google Scholar]

- 34f. Sadek H., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 5902–5904; [Google Scholar]

- 34g. Sadek H., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 5897–5901; [Google Scholar]

- 34h. Sadek H., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 4507–4512; [Google Scholar]

- 34i. Hirsch E., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 1018–1022; [Google Scholar]

- 34j. Berns D. S., Fuoss R. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 5585–5588. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Houk K. N., Nakamura K., Sheu C. M., Keating A. E., Science 1996, 273, 627–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ro S., Rowan S. J., Pease A. R., Cram D. J., Stoddart J. F., Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2411–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davis A. V., Raymond K. N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7912–7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murase T., Fujita M., Chem. Rec. 2010, 10, 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary