Abstract

Background

Primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver (PCCCL) is an infrequent variant of primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), we retrospectively performed a large population-based cohort study to elucidate the relationships between demographic, carcinoma- and therapy-specific variables and overall survival (OS).

Material/Methods

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database was queried to extract data on 419 patients with pathologically confirmed PCCCL from 1988 to 2015. A nomogram with good accuracy was formulated to predict long-term survival of PCCCL patients.

Results

The OS for PCCCL patients was 25.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 22.2–29 months), the overall 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 59.5%, 39.3%, and 29.9%, respectively. Log-rank analysis revealed that there was no statistically significant discrepancy in clinical outcome between PCCCL and common-type HCC after propensity-matched analysis. Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed that larger lesions (>96 mm), distant metastases and elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were independent prognostic factors for undesirable outcome. Conversely, surgery was an independent protective factor (hazard ratio [HR]=0.23, 95% CI 0.17–0.31), which significantly boosted OS by virtually 35 months (47.3 months versus 12.7 months, P<0.001). Radiotherapy or chemotherapy was not associated with OS for PCCCL patients (both P>0.05). The nomogram incorporated 4 independent prognostic factors and its concordance index for predicting survival was 0.761.

Conclusions

The prognosis of PCCCL resembled that of common-type HCC. Larger lesions, distant metastases, and enhanced AFP levels were associated with unsatisfactory prognosis. Surgery fulfill favorable prognosis while radiotherapy or chemotherapy exerted no significant effects on survival.

MeSH Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Clear Cell; Carcinoma, Hepatocellular; Nomograms; Prognosis; SEER Program

Background

Clear cell carcinoma prevailingly occurs in the ovary [1] and kidney [2], however, it has been rarely reported in additional locations like the lungs [3], liver [4]. Primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver (PCCCL) is an uncommon pathological subtype of primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with insufficient comprehension of its clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors on account of merely few case reports or clinical cohort studies from small, single institution. PCCCL is commonly endowed with a low-grade malignancy and distinct histopathological profile [5]. It is pathologically characterized by prominent cytoplasmic accumulation of abundant glycogen or/and lipid that are dissolved during hematoxylin and eosin staining, thereby merely showing a clear cytoplasm [6]. PCCCL can develop at any age, with a peak incidence in male patients aging from 50 to 60 years old [4].

The most pressing risk factor for PCCCL is hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, while PCCCL is not significantly correlative with alcoholism, hepatitis B virus infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hemochromatosis, and autoimmune liver disease [7]. The onset and clinical manifestations of PCCCL basically resemble those of HCC, characterized by certain unspecific symptoms, such as right upper quadrant pain, fatigue, and anorexia and generally concomitant with medical history of viral hepatitis and cirrhosis as well as elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. Therefore, early detection of PCCCL is difficult. Frequently, representative imaging characteristics of PCCCL are inchoate enhancement and fast washout of contrast medium on dynamic contrast scans, and existence of portal vein thrombus or phyma rupture [8].

Notably, studies have shown that PCCCL cases account for 0.4% to 37% of all HCCs, and these variable reports are primarily attributable to the inconsistency of pathologically diagnostic criteria for such tumor. More precisely, Lai et al. indicated that PCCCL could be diagnosed even though clear cells proportion was less than 30% [9]. In contrast, another study implicated that the definite diagnosis of PCCCL should be made under the condition that clear cells proportion represented over 30% [10]. The majority of physicians support that when clear cells occupy more than 50% through histological examination, it should be diagnosed as PCCCL [11–14]. And PCCCL merely accounts for 2.2–6.7% of all HCC in a large proportion of studies through utilizing this criterion [11,15]. Indeed, Liu et al. reported that PCCCL merely occupied approximately 3.5% of primary HCC in their hospital [15]. Notably, PCCCL is stuck in a diagnostic predicament without the assistance of immunohistochemical staining, as cytokeratin profiling and evidence of immunoreactivity for AFP and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) are presumably a beneficial criterion to differentiate PCCCL from metastatic clear cell carcinomas originated from adrenals, kidneys, ovaries, and additional tissues [16]. To date, surgical intervention is considered to be the optimal treatment modality for PCCCL. Most patients receiving surgical resection have a desirable curative effect and a promising long-term survival rate.

In accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, version 3 (ICD-O.3), PCCCL is recognized as one of the subtypes of primary HCC [17]. Because of its rarity, a large number of previous studies are centralized case reports or series or small cohort study from single institutions. Currently, its clinicopathological and prognostic features are not fully elucidated in the literature. Therefore, in our study, we retrospectively analyzed the demographic and clinicopathological information of 419 PCCCL patients registered in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database between 1988 and 2015, which was instrumental in unveiling the prognostic factors influencing its survival.

Material and Methods

Data source

Original information was excavated from the SEER database supported by the National Cancer Institute. The SEER program was comprised of 18 population-based cancer registries, covering ~28% of the US population. The SEER program is publicly accessible, which merely contains anonymized patient information. Thus, our study was exempt from the ethical review or the patient consent.

Patient enrollment

We incorporated all patients with the histologically diagnosed 8174/3 (hepatocellular carcinoma, clear cell type) based on the ICD-O-3/WHO 2008, ranging from 1988 to 2015 registered in the SEER database. Only patients >18 years of age with PCCCL as their “one primary only” tumor were incorporated in the study dataset. Moreover, records with insufficient information concerning survival, histology, or staging data (including tumor size and extension) were eliminated. We stratified total cohort based upon both demographic and clinicopathological characteristics such as age at diagnosis, gender, ethnicity, marital status at diagnosis, pathological differentiation grade, AFP interpretation, fibrosis, tumor size, lymph node invasion, distant metastases, SEER summary stage, TNM stage, and whether surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy were received.

Statistical analysis

We downloaded all the data from SEER*Stat Software version 8.3.5 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA). Statistical analysis was implemented by the software SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A Student’s t-test was applied to make a contrast of continuous variables and a chi-squared test was utilized to compare categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier approach was utilized to estimate survival probabilities and a log-rank test was applied to evaluate significant differences in overall survival (OS) stratified by respective covariate. Cox regression analysis was utilized to analyze the correlations between prognostic factors and OS or CSS. We carried out a propensity-score matching (PSM) analysis at a 1: 1 ratio between PCCCL patients and patients pathologically confirmed common-type HCC over the same time period from the SEER database, which modulated the differences between PCCCL and common-type HCC group to compare their prognoses. X-tile software was applied to resolve the optimal cutoff levels of prognostic factors and R language 3.5.3 Software with the rms and survival packages was used to determine the prognostic nomogram, concordance index (C-index), and calibration curve. Two tailed P<0.05 was defined to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Our data consisted of a total of 419 qualified patients with PCCCL. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of such patients are depicted in Table 1. The number of patients who underwent cancer-oriented surgery was 157 patients (37.5%) in the PCCCL group. Chemotherapy was performed for 29.8% of cases, Supplementary Table 1 shows that younger PCCCL patients with larger or remotely metastatic lesions and elevated AFP levels as well as advanced disease stage were prone to receive chemotherapy. Additionally, patients managed by some form of radiotherapy merely accounted for 6.2% of patients. Analogously, as is shown in Supplementary Table 2, PCCCL patients who were administered with radiotherapy were characterized by larger or metastatic lesions, advanced disease stage and increased AFP levels, compared with those without radiation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 419 patients with PCCCL.

| Characteristics | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 419 | |

| Age (years) | 64.4±12.3 | |

| ≤60 | 165 | 31.8% |

| 61–70 | 117 | 22.5% |

| >70 | 137 | 26.4% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 151 | 36.0% |

| Male | 268 | 64.0% |

| Race | ||

| White | 275 | 65.6% |

| Black | 48 | 11.5% |

| Unknown | 96 | 22.9% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 332 | 79.2% |

| Single | 73 | 17.4% |

| Unknown | 14 | 3.3% |

| Grade | ||

| Well; I | 63 | 15.0% |

| Moderately; II | 113 | 27.0% |

| Poorly; III | 38 | 9.1% |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 6 | 1.4% |

| Unknown | 199 | 47.5% |

| Tumor stage | ||

| T1 | 168 | 40.1% |

| T2 | 60 | 14.3% |

| T3 | 74 | 17.7% |

| T4 | 94 | 22.4% |

| Unknown | 23 | 5.5% |

| Lymph node metastases | ||

| N0 | 326 | 77.8% |

| N1 | 19 | 4.5% |

| Unknown | 74 | 17.7% |

| Distant metastases | ||

| M0 | 325 | 77.6% |

| M1 | 74 | 17.7% |

| Unknown | 20 | 4.8% |

| Summary stage | ||

| Localized | 226 | 53.9% |

| Regional | 99 | 23.6% |

| Distance | 74 | 17.7% |

| Unknown | 20 | 4.8% |

| TNM stage | ||

| I | 136 | 32.5% |

| II | 51 | 12.2% |

| III | 91 | 21.7% |

| IV | 74 | 17.7% |

| Unknown | 67 | 16.0% |

| AFP level | ||

| Elevated | 191 | 45.6% |

| Normal | 62 | 14.8% |

| Unknown | 166 | 39.6% |

| Fibrosis score | ||

| 0–4 | 42 | 10.0% |

| 5–6 | 45 | 10.7% |

| Unknown | 332 | 79.2% |

| Surgery type | ||

| Local ablation | 28 | 17.8% |

| Resection | 115 | 73.2% |

| Transplant | 13 | 8.3% |

| Surgery with unknown type | 1 | 0.6% |

| Surgery | ||

| No | 259 | 61.8% |

| Yes | 157 | 37.5% |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.7% |

| Radiation | ||

| No | 393 | 93.8% |

| Yes | 26 | 6.2% |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 294 | 70.2% |

| Yes | 125 | 29.8% |

PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver; AFP – alpha-fetoprotein.

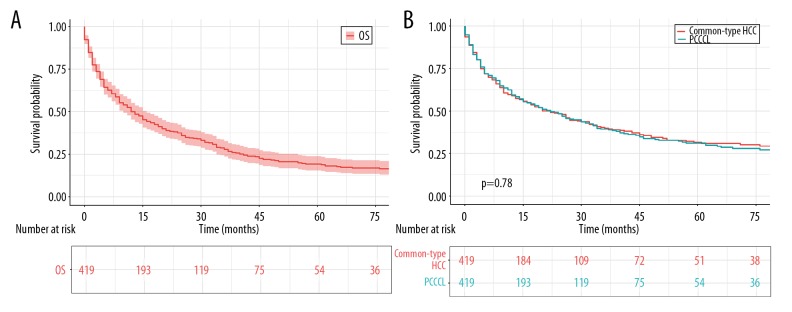

Patient survival

The mean survival time of such PCCCL patients was 25.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 22.2–29) (Figure 1A, Table 2). The overall 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival probability was 59.5%, 39.3%, and 29.9%, respectively (Table 3). In an attempt to explore the prognostic difference between PCCCL patients and common-type HCC patients, 419 PCCCL patients were matched with 419 patients who were pathologically diagnosed common-type HCC ranging from 1988 to 2015 (1: 1) in the SEER database. As was revealed in Supplementary Table 3, there were no statistically significant discrepancies in clinical characteristics after PSM analysis. Concerning clinically prognostic outcomes at PCCCL patients versus their counterparts with common-type HCC, survival curves and log-rank analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

OS for patients with PCCCL. (A) OS for 419 patients with PCCCL. (B) OS comparison between PCCCL and common type. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver; HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma; PSM – propensity-score matching.

Table 2.

Overall survival stratified by clinical features and univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses for PCCCL patients.

| Variables | Mean survival months | 95% CI | Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95%CI] | P-value | |||

| Total | 25.6 | 22.2–29 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤60 | 27.7 | 21.6–33.8 | Ref | |

| 61–70 | 30.5 | 23.6–37.5 | 0.93 (0.68–1.27) | 0.665 |

| >70 | 18.8 | 14.5–23.2 | 1.22 (0.9–1.64) | 0.200 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 33.1 | 22.5–33.1 | Ref | |

| Male | 36.6 | 20–28.8 | 1.04 (0.8–1.34) | 0.793 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 25.6 | 21.4–29.9 | Ref | |

| Black | 21.3 | 12.1–30.6 | 1.14 (0.77–1.69) | 0.517 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 27.1 | 23.1–31.1 | Ref | |

| Single | 19.6 | 13.4–25.8 | 1.33 (0.97–1.83) | 0.079 |

| Grade | ||||

| Well | 31.6 | 22.3–40.8 | Ref | |

| Moderately | 31.3 | 24.8–37.8 | 0.82 (0.55–1.24) | 0.358 |

| Poor and undifferentiated | 34.5 | 20.5–48.5 | 0.96 (0.58–1.59) | 0.872 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| T1 | 36.9 | 30.5–43.3 | Ref | |

| T2 | 32.8 | 22.3–43.3 | 1.08 (0.7–1.68) | 0.723 |

| T3 | 12.6 | 8.7–16.5 | 3.2 (2.25–4.56) | <0.001 |

| T4 | 14.1 | 9.4–18.8 | 3.01 (2.16–4.19) | <0.001 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤37 mm | 49.2 | 39.7–58.7 | Ref | |

| 37–96 mm | 28.7 | 23.1–34.4 | 2.7 (1.79–4.12) | <0.001 |

| >96 mm | 15.1 | 10.1–20.1 | 5.28 (3.37–8.28) | <0.001 |

| Lymph node metastases | ||||

| N0 | 28.4 | 24.4–32.4 | Ref | |

| N1 | 8.1 | 3.8–12.3 | 2.63 (1.51–4.58) | <0.001 |

| Distant metastases | ||||

| M0 | 30.4 | 26.2–34.6 | Ref | |

| M1 | 7.7 | 5.1–10.3 | 3.25 (2.38–4.45) | <0.001 |

| Summary stage | ||||

| Localized | 35.7 | 30.5–41 | Ref | |

| Regional | 18.3 | 12.4–24.2 | 2.11 (1.55–2.88) | <0.001 |

| Distance | 7.7 | 5.1–10.3 | 4.17 (2.98–5.84) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 39.9 | 32.9–46.9 | Ref | |

| II | 35.7 | 23.7–47.7 | 1.04 (0.62–1.73) | 0.882 |

| III | 17.4 | 12.3–22.5 | 3.03 (2.11–4.36) | <0.001 |

| IV | 7.7 | 5.1–10.3 | 5.73 (3.88–8.46) | <0.001 |

| AFP level | ||||

| Elevated | 22.3 | 17.8–26.7 | Ref | |

| Normal | 31.9 | 23.9–39.9 | 0.51 (0.34–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Fibrosis score | ||||

| 0–4 | 28.2 | 20.3–36.2 | ||

| 5–6 | 33.6 | 21.7–45.4 | 1.09 (0.61–1.95) | 0.790 |

| Surgery type | ||||

| Local ablation | 33 | 22.8–43.3 | Ref | |

| Resection | 45.2 | 37.4–53.1 | 0.99 (05–1.97) | 0.980 |

| Transplant | 100.2 | 65.0–135.4 | 0.1 (0.01–0.77) | 0.02 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No | 12.7 | 10.3–15 | Ref | |

| Yes | 47.3 | 40.3–54.4 | 0.23 (0.17–0.31) | <0.001 |

| Radiation | ||||

| No | 26.3 | 22.7–29.9 | Ref | |

| Yes | 15.7 | 9.2–22.3 | 1.4 (0.87–2.27) | 0.169 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 26.1 | 21.7–30.4 | Ref | |

| Yes | 24.6 | 19.3–29.8 | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) | 0.441 |

PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver; AFP – alpha-fetoprotein; CI – confidence interval; HR – hazard ratio.

Table 3.

1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates stratified by clinical features for PCCCL patients.

| Characteristics | Cancer specific survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-years survival | 95% CI | 3-years survival | 95% CI | 5-years survival | 95% CI | |

| Total | 0.595 | 0.55–0.65 | 0.393 | 0.34–0.45 | 0.299 | 0.25–0.36 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤60 | 0.565 | 0.49–0.65 | 0.417 | 0.34–0.51 | 0.348 | 0.27–0.45 |

| 61–70 | 0.656 | 0.57–0.75 | 0.434 | 0.35–0.55 | 0.327 | 0.24–0.45 |

| >70 | 0.574 | 0.49–0.67 | 0.312 | 0.23–0.42 | 0.219 | 0.14–0.35 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 0.646 | 0.57–0.73 | 0.377 | 0.3–0.47 | 0.293 | 0.22–0.39 |

| Male | 0.565 | 0.51–0.63 | 0.408 | 0.35–0.48 | 0.304 | 0.24–0.39 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 0.591 | 0.53–0.66 | 0.383 | 0.32–0.46 | 0.293 | 0.23–0.37 |

| Black | 0.468 | 0.34–0.65 | 0.348 | 0.23–0.54 | \ | \ |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.659 | 0.6–0.73 | 0.460 | 0.39–0.54 | 0.395 | 0.33–0.48 |

| Single | 0.499 | 0.42–0.59 | 0.279 | 0.21–0.37 | 0.161 | 0.1–0.26 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Well | 0.654 | 0.55–0.79 | 0.450 | 0.33–0.61 | 0.323 | 0.21–0.51 |

| Moderately | 0.720 | 0.64–0.81 | 0.499 | 0.4–0.62 | 0.393 | 0.3–0.52 |

| Poor and undifferentiated | 0.725 | 0.6–0.88 | 0.356 | 0.23–0.55 | \ | \ |

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| T1 | 0.746 | 0.68–0.82 | 0.588 | 0.51–0.68 | 0.47 | 0.39–0.57 |

| T2 | 0.706 | 0.59–0.84 | 0.470 | 0.34–0.65 | \ | \ |

| T3 | 0.422 | 0.32–0.57 | 0.150 | 0.08–0.29 | 0.0501 | 0.01–0.19 |

| T4 | 0.400 | 0.31–0.52 | 0.170 | 0.1–0.29 | 0.0969 | 0.04–0.26 |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| ≤37 mm | 0.928 | 0.87–0.99 | 0.781 | 0.69–0.88 | 0.633 | 0.52–0.77 |

| 37–96 mm | 0.646 | 0.57–0.73 | 0.402 | 0.32–0.5 | 0.281 | 0.21–0.38 |

| >96 mm | 0.397 | 0.3–0.53 | 0.147 | 0.08–0.28 | \ | \ |

| Lymph node metastases | ||||||

| N0 | 0.659 | 0.61–0.72 | 0.442 | 0.39–0.51 | 0.34 | 0.28–0.41 |

| N1 | 0.240 | 0.1–0.56 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| Distant metastases | ||||||

| M0 | 0.672 | 0.62–0.73 | 0.460 | 0.4–0.53 | 0.354 | 0.3–0.43 |

| M1 | 0.242 | 0.16–0.38 | 0.061 | 0.02–0.2 | \ | \ |

| Summary stage | ||||||

| Localized | 0.741 | 0.68–0.8 | 0.533 | 0.47–0.61 | 0.425 | 0.35–0.51 |

| Regional | 0.498 | 0.4–0.62 | 0.273 | 0.19–0.4 | 0.172 | 0.1–0.31 |

| Distance | 0.224 | 0.14–0.36 | 0.061 | 0.02–0.2 | \ | \ |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I | 0.798 | 0.73–0.87 | 0.647 | 0.56–0.74 | 0.516 | 0.42–0.63 |

| II | 0.761 | 0.65–0.9 | 0.546 | 0.4–0.74 | \ | \ |

| III | 0.565 | 0.47–0.69 | 0.199 | 0.12–0.33 | 0.083 | 0.03–0.22 |

| IV | 0.224 | 0.14–0.36 | 0.092 | 0.04–0.22 | \ | \ |

| AFP level | ||||||

| Elevated | 0.535 | 0.47–0.62 | 0.315 | 0.25–0.4 | 0.272 | 0.21–0.36 |

| Normal | 0.803 | 0.7–0.92 | 0.612 | 0.48–0.78 | 0.386 | 0.25–0.61 |

| Surgery type | ||||||

| Local ablation | 0.841 | 0.71–1 | 0.725 | 0.55–0.95 | \ | \ |

| Resection | 0.854 | 0.79–0.93 | 0.627 | 0.53–0.74 | 0.481 | 0.38–0.61 |

| Transplant | 0.873 | 0.75–1 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| Surgery (Y/N) | ||||||

| No | 0.430 | 0.37–0.5 | 0.192 | 0.14–0.26 | 0.1176 | 0.07–0.19 |

| Yes | 0.850 | 0.79–0.91 | 0.681 | 0.61–0.77 | 0.573 | 0.49–0.67 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| No | 0.600 | 0.55–0.65 | 0.403 | 0.35–0.46 | 0.316 | 0.26–0.38 |

| Yes | 0.523 | 0.36–0.76 | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 0.562 | 0.51–0.63 | 0.434 | 0.38–0.5 | 0.349 | 0.29–0.42 |

| Yes | 0.667 | 0.59–0.76 | 0.310 | 0.23–0.42 | 0.234 | 0.16–0.35 |

PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

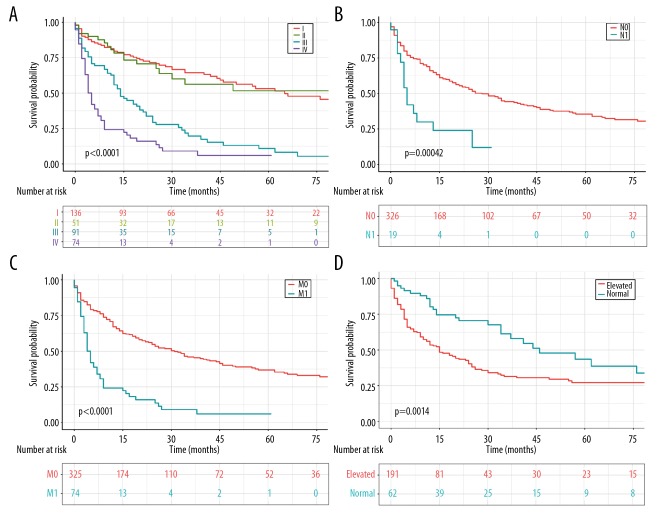

OS analysis stratified by clinical features was revealed in Table 2. The OS of patients was not correlated with age (Supplementary Figure 1A). Based on SEER summary stage, patients with more advanced disease stage were endowed with a much more unfavorable prognosis, compared with those with localized or regional disease (Supplementary Figure 1B). Indeed, the 3-year survival rate for patients with localized and regional lesions was 53.3% and 27.3%, respectively, compared with merely 6.1% for patients with distant lesions (Table 3). Analogously, the 1-year and 3-year survival rates for patients with TNM I, II, and III stage were 79.8%, 76.1%, 56.5%, and 64.7%, 54.6%, 19.9%, respectively, compared with merely 22.4% and 9.2% in patients with IV stage disease (Table 3, Figure 2A). Predictably, both lymph node involvement and remotely metastatic lesions in PCCCL patients were intimately associated with adverse clinical outcomes (Figure 2B, 2C). Enhanced levels of AFP were correlated with significantly diminished mean survival time (22.3 months versus 31.9 months, P<0.01) (Figure 2D). Unexpectedly, the outcome of patients with well or moderately pathologically differentiated tumor was not better than those with poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumor (Supplementary Figure 1C), which is deserved to be further discussed. Furthermore, liver fibrosis imposed no significant effect on OS (Supplementary Figure 1D).

Figure 2.

OS for patients with PCCCL stratified by (A) different TNM stages. (B) Lymph node metastases. (C) Distant metastases. (D) AFP levels. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver; AFP – alpha-fetoprotein.

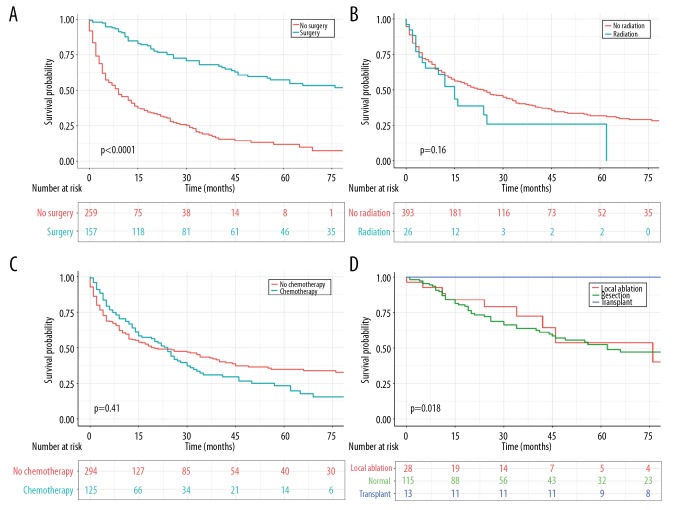

Additionally, cancer-targeted surgery was capable of significantly prolonging survival time and improving clinical effects (Figure 3A). The OS was 47.3 months for patients administered with surgical procedures, which remarkably exceeded the 12.7 months OS of those who did not receive surgery (P<0.001). We also utilized survival curves to compare the efficacy of different surgical categories. As a whole, patients who received a hepatic transplant had a much more satisfactory prognosis than those who underwent local ablation or resection (P<0.01 for both) (Table 2, Figure 3D). To eliminate several confounding factors, we performed PSM analysis and thus made two conclusions. That is, patients who received radiotherapy showed no statistically significant differences in OS compared with those without radiotherapy (Figure 3B). Similarly, no significant relationship between chemotherapy and survival benefits was revealed (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

OS for patients with PCCCL stratified by (A) surgery. (B) Radiation. (C) Chemotherapy. (D) Different surgical strategies. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses

Prognostic factors for OS of PCCCL are depicted in Tables 2 and 4. For the univariate analysis (Table 2), large lesion size, lymph node invasion, and remotely metastatic lesions, more advanced TNM stage and SEER stage as well as elevated AFP levels were the risk factors associated with unfavorable prognosis, in contrast, to confer surgical treatment to patients had the capacity to effectively boost OS (P<0.05 for all). In addition to TNM stage and SEER stage, additional aforementioned univariate analysis was included in the multivariate Cox analysis. This is because both stages overlapped with tumor size, lymph node invasion, and distant metastases [18]. As was revealed in multivariate Cox analysis (Table 4), larger or remotely metastatic lesions in conjunction with increased AFP levels were all independent adverse prognostic factors for PCCCL (P<0.05 for all). Conversely, surgical intervention was sufficient to diminish the risk of death in contrast to non-surgical treatment (HR=0.23, 95% CI 0.17–0.31, P<0.001), indicating that surgical treatment was an independent protective factor for enhanced OS.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses of clinical features for overall survival rates in PCCCL patients.

| Variables | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | P-value | |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≤37 mm | Ref | |

| 37–96 mm | 2.54 (1.66–3.89) | <0.001 |

| >96 mm | 4.56 (2.86–7.29) | <0.001 |

| Lymph node metastases | ||

| N0 | Ref | |

| N1 | 1.32 (0.73–2.37) | 0.361 |

| Distant metastases | ||

| M0 | Ref | |

| M1 | 1.45 (1.02–2.06) | 0.038 |

| AFP level | ||

| Elevated | Ref | |

| Normal | 0.57 (0.37–0.88) | 0.010 |

| Surgery | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.29 (0.21–0.4) | <0.001 |

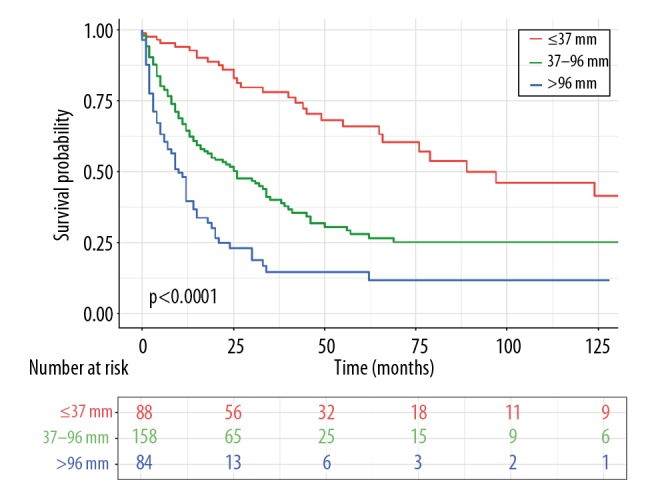

Specifically, larger lesions (>96 mm) exerted a negative impact on the survival time of PCCCL patients (Figure 4, Table 2). Moreover, X-tile program demonstrated that 37 mm and 96 mm were the optimal cut-points to predict prognosis for tumor size (Supplementary Figure 2). In terms of the optimal cut-points, incorporated PCCCL patients could be classified into 3 groups which displayed statistically significant differences in size-associated OS via the Kaplan-Meier curve analysis.

Figure 4.

OS for patients with PCCCL stratified by tumor size. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver; AFP – alpha-fetoprotein; CI – confidence interval; HR – hazard ratio.

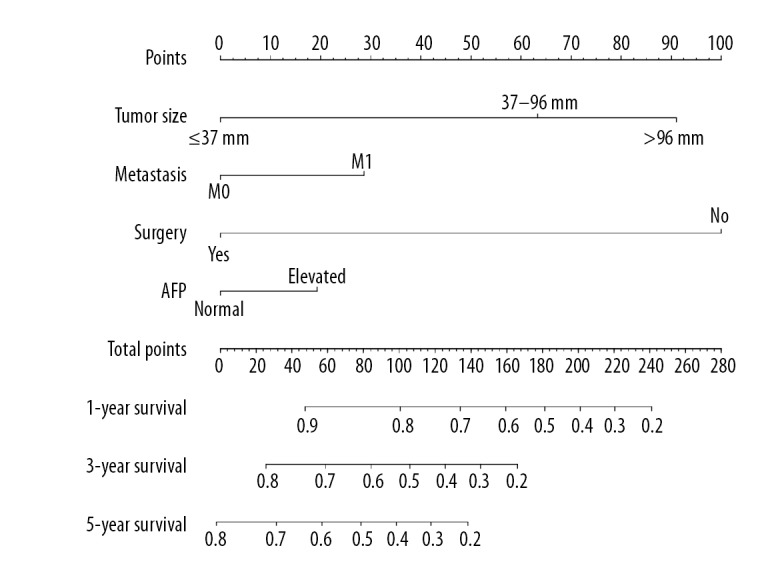

Prognostic nomogram for PCCCL

In an attempt to predict long-term survival of PCCCL patients, a nomogram was further formulated by incorporating all significant independent indicators for OS identified by the multivariate analyses. As was illustrated in Figure 5, surgery and tumor size made the greatest contributions to clinical prognosis, followed by metastasis category and AFP levels. The C-index for OS prediction was 0.761, and thereby the predictive accuracy of such nomogram was relatively satisfactory. The calibration curves for the OS probability of 1-year, 3-year or 5-year in PCCCL patients cohort displayed an optimal consistency between the prediction via nomogram and practical surveillance (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Prognostic nomogram estimated by clinical features for the overall 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rate in PCCCL patients. PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

Discussion

PCCCL is a specific and uncommon histological type of HCC, characterized with clear cells embracing glycogen decorated in tubular, papillary, and solid designs [19], whose low incidence in clinical practice has imposed restrictions on our comprehensive understanding of its clinicopathological and prognostic characteristics. In our study, we depicted the clinicopathological features and demonstrated factors influencing OS of 419 PCCCL patients extracted from the SEER database from 1988 to 2015. Additionally, we formulated a prognostic nomogram with satisfactory accuracy for intuitively predicting 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rate of PCCCL patients.

Our study revealed that the age of patients diagnosed with PCCCL ranged from 52 to 76 years old and a large proportion of patients included in the overall cohort were white (65.6%, 275 of 419), which was roughly consistent to the results of the Jernigan et al. study [20]. There was a male preponderance collectively, accounting for 64.0% of total patients, which was a little lower than 69.6% reported in a literature review [21]. Patients had larger tumor size (>96 mm) in the present study in comparison with the previous report representing a tumor diameter of 50 mm, which was correlated with more aggressive PCCCL, respectively [22]. Of patients with PCCCL in the cohort with recorded pathological differentiation grade, tumor with moderate differentiation occupied a maximal proportion (27.0%, 113 of 419), which corresponded to the description in additional studies [4,16,20]. Of those who have undergone lymph node examinations, lymph node metastases were not usual, representing merely 4.5%, which was also reflected in the TNM pathologic stage, with more likely to be stage I or II, indicating the relatively indolent biology of PCCCL. Accumulating evidence from previous sporadic cases also supported the notion that the majority of PCCCL cases were moderately differentiated, concomitant with comparatively low metastatic potential [4,20,23]. However, a retrospective clinical study showed that up to 18.75% of patients displayed lymph node metastasis and thus 65.6% of them were pathologically diagnosed at TNM stage III or IV through analyzing 64 patients with PCCCL in their hospital [5]. A large proportion of patients with PCCCL were accompanied by elevated AFP levels, which were in accordance with additional researches results [4,7,23]. Notably, severe hepatic fibrosis, classically considered as one of indicators of liver inflammation, did not account for a higher proportion in PCCCL patients. Nevertheless, some previous studies revealed that the majority of patients with PCCCL were primarily on the basis of hepatic cirrhosis that was independent risk factors for OS of PCCCL [7,8,23,24].

In the current report, there was no statistically significant discrepancy in prognosis between PCCCL patients and those with common-type HCC. Nevertheless, the prognosis of PCCCL patients is being debated. Multiple studies showed that PCCCL had a more favorable prognosis than additional HCC [5,9,25,26]. A study demonstrated that the clinical outcome seemed to be better in PCCCL patients than their common-type counterparts, and the survival time enhanced with an accumulating apportion of clear cells [9]. Oppositely, some studies revealed that the prognosis of PCCCL patients was analogous to that of those with common-type HCC and potentially even worse [12–14]. Based on our univariate analysis, advanced TNM and SEER summary disease stages were both correlated with adverse prognosis in PCCCL patients. Indeed, OS of PCCCL patients with TNM-I was 36.9 months, compared with merely 14.1 months for patients with TNM-IV. Intriguingly, the present study, unlike the results from additional cohort studies that pathological differentiation degree was one of the valuable prognostic factors in PCCCL, seemed to display no statistically significant dissimilarity in OS in accordance with the pathological differentiation conditions in this tumor. Such inconsistency was supposed to reflect the relatively small sample size and the actuality that cases were primarily composed of tumor with well or moderately pathological differentiation [5,22]. Notably, lymph node metastasis was also a pivotal risk factor in PCCCL in univariate analysis, which would not influence patient OS after modulating for additional variables in multivariate analysis. The reason behind this phenomenon potentially is that our study could acquire very few PCCCL cases with lymph node metastasis from the SEER database. Cox multivariate analysis indicated that patients with larger lesions (> 96 mm) and distant dissemination as well as elevated AFP levels were related to unsatisfactory survival time. Therefore, early detection and surgical treatment may be of great essential to reap optimal outcomes for PCCCL patients.

Cox multivariate analysis indicated that surgical treatment was regarded as the most promising therapeutic intervention to fulfill satisfactory outcomes and reduced the risk of death of PCCCL patients. The 5-year survival rate for patients with PCCCL would reach up to 57.3% if patients undergo surgery timely. Indeed, a prior study also showed that 1-year and 3-year survival rates of all 13 patients managed by surgical resection was 76.5% and 47.1%, respectively, and the longest survival time was up to 97 months [15]. Similarly, a 55-year-old male patient with retroperitoneal and intrahepatic metastasis of PCCCL was performed with surgical resection and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), without any recurrence and metastasis during 16 months follow-up [16]. Theoretically, PCCCL is characterized by relatively tardy progress, better tumor differentiation, easier pseudo-capsule formation, lower vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis, which all make great contributions to its high resectability rate [5]. Notably, Liu et al. revealed a much higher formation rate of pseudo-capsule in patients with PCCCL than in non-PCCCL HCC patients (75% versus 49.6%, P<0.05) [8]. Such pseudo-capsule is primarily composed of peritumoral hepatic sinusoids with or without fibrosis [7]. With regard to surgical strategies, we found that liver transplantation had the first-rank clinical outcome, followed by surgical resection and local tumor destruction, and surgical resection was still the most momentous and routine tactic to achieve long-term survival for most HCC patients, which was backed up by other studies [20,27]. Currently, literature is confined to researches utilizing surgical resection as the central therapeutic intervention for PCCCL and there are merely several cases of PCCCL that are managed by hepatic transplantation [28]. On account of the rarity of PCCCL cases, confined clinical knowledge is accessible to non-surgical manipulations, including radiofrequency ablation, TACE, percutaneous ethanol injection, or sorafenib as principal intervention measures [7]. For example, in another retrospective study, of those managed by surgical therapy, 81.9% of patients received surgical resection, 16% of them underwent orthotopic liver transplant, and 0.21% of cases were administered with local ablative procedures. And transplantation conferred an obvious and preponderant survival advantage over resection or local ablation [20].

Currently, the efficacy of chemotherapy or radiotherapy as primary intervention or as adjuvant treatment for the prognosis of patient with PCCCL still remains controversial [16]. Our study revealed that both chemotherapy and radiotherapy failed to be considered as prognostic factors and thus were not sufficient to accomplish long-term survival, which potentially was partly attributed to worse physical status of PCCCL patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy. Additionally, a report considered that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with calcium folinate and tegafur resulted in no significant improvement in the survival time of PCCCL patients [5]. Similarly, 3 other case reports regarding unresectable PCCCL patients also approved the opinion that PCCCL was not susceptive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, exhibiting undesirable survival time [12,16,29]. Intriguingly, in 2019, a case report firstly discovered that sunitinib-based systematic therapy clinically cured a male PCCCL patient with multiple metastatic lesions [30]. However, as this is merely a case study, the evidence level of such treatment is extremely finite. Whether chemotherapy or radiotherapy exerts conducive effects on the prognosis of PCCCL patients are needed for further investigation.

Notably, in our current study, an exploratory analysis of a rare type of HCC embraced the largest number of PCCCL patients to date, which was accomplished through utilizing large multi-institution databases. PSM analysis further potentiated the credibility of our findings. To our knowledge, we formulated the first nomogram to predict the survival of PCCCL patients, which depended on the SEER database with long-term follow-up. Physicians and patients will have the capacity to produce individualized survival predictions via such an available scoring system. However, it is pivotal to avert overfitting of the model and determined generalizability through validating the nomogram [3].

Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that this study had several limitations which are intrinsic to any retrospective analyses of SEER database. The SEER database failed to confer the comprehensive data concerning the risk factors for tumorigenesis, such as HCV infection, liver cirrhosis [6]. The SEER database also does not provide the momentous additional evaluation indicators to allow for convincing reflection on the severity degree of PCCCL, such as Child-Pugh classification, large vascular invasion or not, and aneuploid deoxyribonucleic acid content [5,15,31]. Both higher proportion of clear cells and capsule formation have been associated with the desirable outcome of the management [4,22], which should be included in this database and thus potentially validate and optimize our nomogram. Indeed, Chen et al. retrospectively analyzed that proportion of clear cells ≥70% indicated better prognosis [22]. Furthermore, specified risk factors regarding PCCCL recurrence are not documented, which limits our capacity to depict therapies patterns administrated after recurrence such as the accurate chemotherapies delivered or radiation schedules. Thirdly, the SEER database merely confers diseases occurring among American population, and additional countries with high incidence of PCCCL fail to be incorporated for integral analysis. Ultimately, the study is retrospective and additional prospective trials are required to investigate to validate a precise conclusion.

Conclusions

Collectively, our study incorporated the comparatively large national sample to reveal certain significant factors influencing PCCCL prognosis. Specifically, larger tumor size, distant metastases, and elevated AFP levels were considered as unfavorably prognostic factors for PCCCL. Oppositely, surgical intervention tended to confer a significant and superior survival advantage to patients, while PCCCL was non-sensitive to chemotherapy and radical therapy. We also formulated an intuitionistic nomogram to readily predict long-term survival, which may be conducive to further facilitating the establishment of clinical management strategies and prospective researches in such patient population.

Supplementary Data

OS for patients with PCCCL stratified by (A) age. (B) different SEER summary stages. (C) pathological differentiation grade. (D) liver fibrosis score. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

The optimal cut-off of tumor size in PCCCL patients. PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

The calibration plots for predicting PCCCL patient survival at (A) 1 years and (B) 3 years, and (C) 5 years. PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

Supplementary Table 1.

Patient features by chemotherapy.

| Characteristics | No chemo- therapy | Chemo- therapy | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 294 | 125 | |

| Age (years) | 65.7±12.3 | 61.4±11.8 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.368 | ||

| Female | 110 | 41 | |

| Male | 184 | 84 | |

| Race | 0.852 | ||

| White | 194 | 81 | |

| Black | 32 | 16 | |

| Unknown | 68 | 28 | |

| Marital status | 0.1 | ||

| Married | 228 | 104 | |

| Single | 58 | 15 | |

| Unknown | 8 | 6 | |

| Grade | 0.91 | ||

| Well; I | 43 | 20 | |

| Moderately; II | 79 | 34 | |

| Poorly; III | 25 | 13 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 4 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 143 | 56 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.03 | ||

| T1 | 128 | 41 | |

| T2 | 40 | 20 | |

| T3 | 43 | 30 | |

| T4 | 63 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 3 | |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.68 | ||

| N0 | 226 | 100 | |

| N1 | 13 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 55 | 19 | |

| Distant metastases | 0.07 | ||

| M0 | 229 | 96 | |

| M1 | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| Summary stage | <0.01 | ||

| Localized | 169 | 57 | |

| Regional | 60 | 39 | |

| Distance | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| TNM stage | <0.01 | ||

| I | 108 | 29 | |

| II | 34 | 17 | |

| III | 51 | 39 | |

| IV | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 54 | 13 | |

| AFP level | <0.001 | ||

| Elevated | 165 | 94 | |

| Normal | 126 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | |

| Surgery | <0.001 | ||

| No | 165 | 94 | |

| Yes | 126 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | |

| Radiation | 0.01 | ||

| No | 282 | 111 | |

| Yes | 12 | 14 |

Supplementary Table 2.

Patient features by radiation.

| Characteristics | No radiation | Radiation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 393 | 26 | |

| Age (years) | 64.6±12.2 | 60.7±13.7 | 0.16 |

| Gender | 0.56 | ||

| Female | 143 | 250 | |

| Male | 8 | 18 | |

| Race | 0.58 | ||

| White | 255 | 20 | |

| Black | 45 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 92 | 4 | |

| Marital status | 0.23 | ||

| Married | 311 | 21 | |

| Single | 70 | 3 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 2 | |

| Grade | 0.29 | ||

| Well; I | 61 | 2 | |

| Moderately; II | 108 | 5 | |

| Poorly; III | 33 | 5 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 6 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 185 | 14 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.37 | ||

| T1 | 161 | 8 | |

| T2 | 56 | 4 | |

| T3 | 70 | 3 | |

| T4 | 86 | 8 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 3 | |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.43 | ||

| N0 | 305 | 21 | |

| N1 | 17 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 71 | 3 | |

| Distant metastases | <0.001 | ||

| M0 | 313 | 12 | |

| M1 | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| Summary stage | <0.001 | ||

| Localized | 222 | 4 | |

| Regional | 91 | 8 | |

| Distance | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| TNM stage | <0.001 | ||

| I | 133 | 4 | |

| II | 49 | 2 | |

| III | 85 | 5 | |

| IV | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 64 | 3 | |

| AFP level | 0.01 | ||

| Elevated | 173 | 18 | |

| Normal | 62 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 158 | 8 | |

| Surgery | 0.1 | ||

| No | 241 | 18 | |

| Yes | 150 | 7 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | |

| Radiation | 0.011 | ||

| No | 282 | 111 | |

| Yes | 12 | 14 |

Supplementary Table 3.

Patient features for PCCCL and common-type HCC after PSM analysis.

| Characteristics | PCCCL | Common-type hepato-cellular | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 419 | 419 | |

| Age (years) | 64.4±12.3 | 64.9±12.0 | 0.50 |

| Gender | 0.38 | ||

| Female | 151 | 139 | |

| Male | 268 | 280 | |

| Race | 0. 81 | ||

| White | 282 | 282 | |

| Black | 48 | 49 | |

| Unknown | 96 | 88 | |

| Marital status | 0.63 | ||

| Married | 332 | 343 | |

| Single | 73 | 64 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 12 | |

| Grade | 0.95 | ||

| Well; I | 63 | 70 | |

| Moderately; II | 113 | 115 | |

| Poorly; III | 38 | 34 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 6 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 194 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.89 | ||

| T1 | 168 | 156 | |

| T2 | 60 | 62 | |

| T3 | 74 | 78 | |

| T4 | 94 | 95 | |

| Unknown | 23 | 28 | |

| Lymph node metastases | |||

| N0 | 326 | 316 | |

| N1 | 19 | 17 | |

| Unknown | 74 | 86 | |

| Distant metastases | 0.73 | ||

| M0 | 325 | 316 | |

| M1 | 74 | 83 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 20 | |

| AFP level | 0.87 | ||

| Elevated | 191 | 184 | |

| Normal | 62 | 66 | |

| Unknown | 166 | 169 | |

| Surgery (Y/N) | 0.58 | ||

| No | 259 | 264 | |

| Yes | 157 | 154 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | |

| Radiation | 0.36 | ||

| No | 393 | 395 | |

| Yes | 26 | 24 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.48 | ||

| No | 294 | 306 | |

| Yes | 125 | 113 | |

Abbreviations

- PCCCL

primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- OS

overall survival

- CI

confidence interval

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- HR

hazard ratio

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- PSM

propensity-score matching

- C-index

concordance index

- EMA

epithelial membrane antigen

- TACE

transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

Footnotes

Source of support: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81872473 (P.Cao)]; the Hunan Province Science and Technology plan [2017SK2052 (P.Cao)]

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bacalbasa N, Balescu I, Filipescu A. Debulking surgery for clear cell carcinoma of the ovary – a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(10):5707–11. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagher J, Kammerer-Jacquet SF, Dugay F, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A comparative study of histological and chromosomal characteristics between primary tumors and their corresponding metastases. Virchows Archiv. 2017;471(1):107–15. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ke SJ, Wang P, Xu B. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lung: A population-based study. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:1003–12. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, Wu X, Bi X, et al. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of four rare subtypes of primary liver carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30(3):364–72. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji SP, Li Q, Dong H. Therapy and prognostic features of primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(6):764–69. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i6.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bannasch P, Ribback S, Su Q, Mayer D. Clear cell hepatocellular carcinoma: Origin, metabolic traits and fate of glycogenotic clear and ground glass cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017;16(6):570–94. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kothadia JP, Kaur N, Arju R, et al. Primary clear cell carcinoma of the non-cirrhotic liver presenting as an acute abdomen: A case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48(2):211–16. doi: 10.1007/s12029-016-9831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu QY, Li HG, Gao M, et al. Primary clear cell carcinoma in the liver: CT and MRI findings. World Journal Gastroenterol. 2011;17(7):946–52. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai CL, Wu PC, Lam KC, Todd D. Histologic prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1979;44(5):1677–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197911)44:5<1677::aid-cncr2820440522>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan TF, Jr, Huvos AG. Clear-cell carcinoma of the liver. A clinicopathologic study of 13 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1974;61(4):529–39. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/61.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z, Ma W, Li H, Li Q. Clinicopathological and prognostic features of primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(3):291–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah S, Gupta S, Shet T, et al. Metastatic clear cell variant of hepatocellular carcinoma with an occult hepatic primary. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4(2):306–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamek HE, Spiethoff A, Kaufmann V, et al. Primary clear cell carcinoma of noncirrhotic liver: Immunohistochemical discrimination of hepatocellular and cholangiocellular origin. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(1):33–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1018859617522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang SH, Watanabe J, Nakashima O, Kojiro M. Clinicopathologic study on clear cell hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Int. 1996;46(7):503–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lao XM, Zhang YQ, Jin X, et al. Primary clear cell carcinoma of liver – clinicopathologic features and surgical results of 18 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53(67):128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong J, He D, Hu W, Liu X. Retroperitoneal and intrahepatic metastasis from primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine. 2017;96(12):e6452. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung ES, Kang YK, Cho MY, et al. Update on the proposal for creating a guideline for cancer registration of the gastrointestinal tumors (I-2) Korean J Pathol. 2012;46(5):443–53. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin BD, Jiao XD, Liu K, et al. Clinical, pathological and treatment factors associated with the survival of patients with primary pulmonary salivary gland-type tumors. Lung Cancer. 2018;126:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harimoto N, Hagiwara K, Yamanaka T, et al. Fairly rare clear cell adenocarcinoma mimicking liver cancer: A case report. Surg Case Rep. 2018;4(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0500-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jernigan PL, Wima K, Hanseman DJ, et al. Natural history and treatment trends in hepatocellular carcinoma subtypes: Insights from a National Cancer Registry. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(8):872–76. doi: 10.1002/jso.24083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu JH, Tsai HL, Hsu SM, et al. Clear cell and non-clear cell hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20(2):78–82. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen ZS, Zhu SL, Qi LN, Li LQ. Long-term survival and prognosis for primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver after hepatectomy. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4129–35. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S104827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T, Fan J, Qin LX, et al. Risk factors, prognosis, and management of early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection of primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(7):1955–63. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1540-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sivrioglu AK, Saglam M, Incedayi M, Sonmez G. Clear cell HCC mimicking to hepatic adenoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008901. pii: bcr2013008901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi A, Saito H, Kanno Y, et al. Case of clear-cell hepatocellular carcinoma that developed in the normal liver of a middle-aged woman. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(1):129–31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvucci M, Lemoine A, Saffroy R, et al. Microsatellite instability in European hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 1999;18(1):181–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Cen D, Yu Y, et al. Does fibrosis have an impact on survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Evidence from the SEER database? BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1125. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4996-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pecorella I, Ciardi A, Aiello E, et al. Clear cell hepatocellular carcinoma treated with liver transplantation. Pathologica. 1994;86(3):307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maharajan K, Hey HWD, Tham I, et al. Solitary vertebral metastasis of primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver: A case report and review of literature. J Spine Surg. 2017;3(2):287–93. doi: 10.21037/jss.2017.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun L, Chen H, Xiao Z, et al. Sunitinib and Chinese herbal medicine-based systematic treatment clinically cured a patient with multiple metastatic primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver: A case report. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2823–28. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S197923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakhuja P, Mishra PK, Rajesh R, et al. Clear cell hepatocellular carcinoma: Back to the basics for diagnosis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(3):656. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.136041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

OS for patients with PCCCL stratified by (A) age. (B) different SEER summary stages. (C) pathological differentiation grade. (D) liver fibrosis score. OS – overall survival; PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

The optimal cut-off of tumor size in PCCCL patients. PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

The calibration plots for predicting PCCCL patient survival at (A) 1 years and (B) 3 years, and (C) 5 years. PCCCL – primary clear cell carcinoma of the liver.

Supplementary Table 1.

Patient features by chemotherapy.

| Characteristics | No chemo- therapy | Chemo- therapy | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 294 | 125 | |

| Age (years) | 65.7±12.3 | 61.4±11.8 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.368 | ||

| Female | 110 | 41 | |

| Male | 184 | 84 | |

| Race | 0.852 | ||

| White | 194 | 81 | |

| Black | 32 | 16 | |

| Unknown | 68 | 28 | |

| Marital status | 0.1 | ||

| Married | 228 | 104 | |

| Single | 58 | 15 | |

| Unknown | 8 | 6 | |

| Grade | 0.91 | ||

| Well; I | 43 | 20 | |

| Moderately; II | 79 | 34 | |

| Poorly; III | 25 | 13 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 4 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 143 | 56 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.03 | ||

| T1 | 128 | 41 | |

| T2 | 40 | 20 | |

| T3 | 43 | 30 | |

| T4 | 63 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 3 | |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.68 | ||

| N0 | 226 | 100 | |

| N1 | 13 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 55 | 19 | |

| Distant metastases | 0.07 | ||

| M0 | 229 | 96 | |

| M1 | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| Summary stage | <0.01 | ||

| Localized | 169 | 57 | |

| Regional | 60 | 39 | |

| Distance | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| TNM stage | <0.01 | ||

| I | 108 | 29 | |

| II | 34 | 17 | |

| III | 51 | 39 | |

| IV | 47 | 27 | |

| Unknown | 54 | 13 | |

| AFP level | <0.001 | ||

| Elevated | 165 | 94 | |

| Normal | 126 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | |

| Surgery | <0.001 | ||

| No | 165 | 94 | |

| Yes | 126 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | |

| Radiation | 0.01 | ||

| No | 282 | 111 | |

| Yes | 12 | 14 |

Supplementary Table 2.

Patient features by radiation.

| Characteristics | No radiation | Radiation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 393 | 26 | |

| Age (years) | 64.6±12.2 | 60.7±13.7 | 0.16 |

| Gender | 0.56 | ||

| Female | 143 | 250 | |

| Male | 8 | 18 | |

| Race | 0.58 | ||

| White | 255 | 20 | |

| Black | 45 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 92 | 4 | |

| Marital status | 0.23 | ||

| Married | 311 | 21 | |

| Single | 70 | 3 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 2 | |

| Grade | 0.29 | ||

| Well; I | 61 | 2 | |

| Moderately; II | 108 | 5 | |

| Poorly; III | 33 | 5 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 6 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 185 | 14 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.37 | ||

| T1 | 161 | 8 | |

| T2 | 56 | 4 | |

| T3 | 70 | 3 | |

| T4 | 86 | 8 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 3 | |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.43 | ||

| N0 | 305 | 21 | |

| N1 | 17 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 71 | 3 | |

| Distant metastases | <0.001 | ||

| M0 | 313 | 12 | |

| M1 | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| Summary stage | <0.001 | ||

| Localized | 222 | 4 | |

| Regional | 91 | 8 | |

| Distance | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2 | |

| TNM stage | <0.001 | ||

| I | 133 | 4 | |

| II | 49 | 2 | |

| III | 85 | 5 | |

| IV | 62 | 12 | |

| Unknown | 64 | 3 | |

| AFP level | 0.01 | ||

| Elevated | 173 | 18 | |

| Normal | 62 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 158 | 8 | |

| Surgery | 0.1 | ||

| No | 241 | 18 | |

| Yes | 150 | 7 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | |

| Radiation | 0.011 | ||

| No | 282 | 111 | |

| Yes | 12 | 14 |

Supplementary Table 3.

Patient features for PCCCL and common-type HCC after PSM analysis.

| Characteristics | PCCCL | Common-type hepato-cellular | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 419 | 419 | |

| Age (years) | 64.4±12.3 | 64.9±12.0 | 0.50 |

| Gender | 0.38 | ||

| Female | 151 | 139 | |

| Male | 268 | 280 | |

| Race | 0. 81 | ||

| White | 282 | 282 | |

| Black | 48 | 49 | |

| Unknown | 96 | 88 | |

| Marital status | 0.63 | ||

| Married | 332 | 343 | |

| Single | 73 | 64 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 12 | |

| Grade | 0.95 | ||

| Well; I | 63 | 70 | |

| Moderately; II | 113 | 115 | |

| Poorly; III | 38 | 34 | |

| Undifferentiated; IV | 6 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 194 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.89 | ||

| T1 | 168 | 156 | |

| T2 | 60 | 62 | |

| T3 | 74 | 78 | |

| T4 | 94 | 95 | |

| Unknown | 23 | 28 | |

| Lymph node metastases | |||

| N0 | 326 | 316 | |

| N1 | 19 | 17 | |

| Unknown | 74 | 86 | |

| Distant metastases | 0.73 | ||

| M0 | 325 | 316 | |

| M1 | 74 | 83 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 20 | |

| AFP level | 0.87 | ||

| Elevated | 191 | 184 | |

| Normal | 62 | 66 | |

| Unknown | 166 | 169 | |

| Surgery (Y/N) | 0.58 | ||

| No | 259 | 264 | |

| Yes | 157 | 154 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | |

| Radiation | 0.36 | ||

| No | 393 | 395 | |

| Yes | 26 | 24 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.48 | ||

| No | 294 | 306 | |

| Yes | 125 | 113 | |