Abstract

Despite the fact that strains belonging to Weissella species have not yet been approved for use as starter culture, recent toxicological studies open new perspectives on their potential employment. The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of a wild Weissella minor (W4451) strain to modify milk viscosity compared to Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, which is commonly used for this purpose in dairy products. To reach this goal, milk viscosity has been evaluated by means of two very different instruments: one rotational viscometer and the Ford cup. Moreover, water holding capacity was evaluated. W4451, previously isolated from sourdough, was able to acidify milk, to produce polysaccharides in situ and thus improve milk viscosity. The ability of W4451 to produce at the same time lactic acid and high amounts of polysaccharides makes it a good candidate to improve the composition of starters for dairy products. Ford cup turned out to be a simple method to measure fermented milk viscosity by small- or medium-sized dairies.

Keywords: Weissella, exopolysaccharides, milk fermentation, starter cultures, viscosity

Introduction

Weissella is a lactic acid bacteria (LAB) frequently isolated from spontaneous fermented foods and is known to have an important role in the development of their particular features (Fessard and Remize, 2017). Nowadays, Weissella species have not yet been approved for commercial use as starter cultures in fermented foods in the United States nor the European Union (Sturino, 2018). However, recent toxicological studies confirmed Weissella confusa to be safe (Cupi and Elvig-Jorgensen, 2019), and Weissella minor (Collins et al., 1993) strains have been classified as BSL1 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009), i.e., low-risk microbes that pose little to no threat of infection in healthy adults. This opens new perspectives in the use of Weissella species as starters in fermented foods. Indeed, Weissella species have already been used in the production of a variety of fermented foods and beverages and also as probiotics (Kang et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Gomathi et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Recently, Kariyawasam et al. (2019) used Weissella as adjunct starter in cottage cheese.

Furthermore, several Weissella species are being extensively studied for their ability to produce significant amounts of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), which can be used as prebiotics or in food industries with different technological applications (Abriouel et al., 2015).

The ability to produce EPS is a common technological feature among LAB, and it may provide thickening, stabilizing, and water-binding effects in fermented foods (Ruas-Madiedo et al., 2002; Zannini et al., 2015; Sanlibaba and Çakmak, 2016). EPS are long chain molecules with a heterogeneous composition and structure, consisting of either branched or not, repeating units of sugars, or sugars derivatives, that exhibit a broad range of physicochemical properties (Malang et al., 2015; Galle and Arendt, 2014). They can be classified according to their chemical composition and biosynthesis mechanism into two main groups: homopolysaccharides that contain one neutral monosaccharide type and heteropolysaccharides that consist of three to eight monosaccharides, derivatives of monosaccharides, or substituted monosaccharides (HePS) (Torino et al., 2015; Oleksy and Klewicka, 2016). The molecular weight of EPS is high, with HePS ranging from 104 to 106 Da, which is generally lower than the average molecular mass of homopolysaccharides, which ranges up to ∼107 Da (Sanlibaba and Çakmak, 2016; Oleksy and Klewicka, 2016).

Application examples of EPS-producing LAB have been recorded for the production of yogurts, fermented milks, beverages, and fresh cheeses to avoid the addition of milk solids and/or concentrate milk, improve the viscosity, texture, stability, and mouthfeel of the final product, as well as to reduce whey syneresis in the coagulated curd after fermentation or upon storage (Torino et al., 2015).

The application of Weissella spp. is quite recent in dairy products (Kimoto-Nira et al., 2011; Lynch et al., 2014), and its ability to produce at the same time lactic acid and high amounts of EPS makes Weissella a good candidate to be included in multispecies culture starters also for dairy beverages and/or fresh cheeses.

On the contrary, among the commonly used LAB as dairy starters, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus has been extensively exploited for the production of EPS in dairy products (Aslim et al., 2005; Schiraldi et al., 2006). In this context, the aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of a wild W. minor strain to increase milk viscosity compared to two Ld. bulgaricus strains.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Weissella minor, W4451 EPS+, Ld. bulgaricus, Ldb2214 EPS+, and Lactococcus lactis Ll 220 EPS−, belonging to the collection of the Food Microbiology Laboratory (Department of Food and Drug, University of Parma, Italy), and Ld. bulgaricus, Ldb147 EPS+, kindly provided by Sacco Srl (Cadorago, Italy), were used. W4451, was isolated by our group from sourdough and identified by mean of 16s rRNA sequencing analysis (Macrogen Europe, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

The strains were maintained at −80°C as frozen stock cultures in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe broth for Weissella and Lactobacillus strains (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and M17 (Oxoid Ltd.) broth for Lactococcus strain, containing 20% (v/v) glycerol. They were recovered by anaerobic incubation in the same media, by two overnight subculturing (2% v/v) at 37°C for Weissella and Lactobacillus and 30°C for Lactococcus.

EPS Characterization by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

The three EPS + strains (W4451, Ldb2214, and Ldb147) were cultivated in semidefined medium (SDM) [Tween 80 (1 ml/L), ammonium citrate (2 g/L), sodium acetate (5 g/L), MgSO4.7H2O (0.1 g/L), MnSO4 (0.05 g/L), K2HPO4 (2 g/L), yeast nitrogen base (5 g/L), casein digest (10 g/L)]. It is useful to provide minimal interference with the assays used to characterize EPS (Kimmel and Roberts, 1998). SDM was autoclaved for 15 min at 121°C, and the lactose (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) aqueous solution (60 g/L), used as carbohydrate source, was sterilized separately (15 min at 121°C) and aseptically added to the medium. The inoculated (2% v/v) broths were incubated at 37°C for Lactobacillus and Weissella (Nguyen et al., 2014) and 30°C for Lc. lactis. Total EPS from the SDM medium were isolated by means of double cold ethanol precipitation method without dialysis (Rimada and Abraham, 2003). The absence of protein and nucleic acids in the EPS was assessed by spectrophotometric analysis using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Jasco V-530), at a wavelength of 260–280 nm (Liu et al., 2016).

Recovered EPS were hydrolyzed with 3 ml 2 M trifluoracetic acid under nitrogen for 60 min at 121°C. To the hydrolyzed mixture, 1 ml phenyl-beta-D-glucopyranoside (500 ppm) was added as internal standard. The samples were clarified by syringe filtration on nylon filters (40 μm), and the filtrate evaporated to dryness with nitrogen. Sugars were silylated for 60 min at 60°C adding 600 μl N-N-dimethylformamide and 200 μl N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide containing 1% trimethylchlorosilane. The gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was carried out using apolar capillary column (HP-5MS, Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, United States) in the conditions previously reported (Müller-Maatsch et al., 2016).

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analyses were performed in duplicate. Identification was performed by comparison with retention times and mass spectra of sugars standards (mannose, xylose, ribose, glucose, galactose, rhamnose, arabinose, and fucose). Quantification was performed by means of internal standard, and results were finally expressed as relative percentages.

Milk Fermentation

Three EPS + strains (W4451, Ldb2214, and Ldb147) were used to perform two subculturing (2% v/v) at 37°C in skim milk powder (SSM) (Oxoid, Ltd.) reconstituted to 9% (w/v) and sterilized at 110°C for 15 min. EPS- strain (Ll 220) was used as negative control to perform two subculturing (2% v/v) at 30°C in SSM. Two percent of the last overnight subcultures were used for batch fermentation, which was performed in a bioreactor (working volume, 0.5 L; Applicon Biotechnology, Schiedam, Netherlands), which was sterilized at 121°C for 15 min.

The fermenter was equipped with software BioXpert Lite (Applikon Biotechnology®) for system control and data acquisition. The temperature was constantly recorded by Pt-100 sensor (Applikon Biotechnology®) and pH by means of Applisensor pH gel sensor (Applikon Biotechnology®).

The fermentation was carried out at 37°C for Lactobacillus and Weissella and 30°C for Lc. lactis and was stopped when the pH reached the value of 4.5 by rapid cooling of fermented milk up to 4°C.

Viscosity Measurement of Fermented Milk

At the end of fermentation, the coagula were broken by means of a rod stirrer (DLH VELP Scientifica®) at 210 rpm for 5 min, and then they were maintained at 4°C for 24 h.

Afterwards, the fermented milk samples (100 ml) were equilibrated at 25°C for 90 min and again stirred at 80 rpm for 5 min to reduce possible structural differences among samples caused by the fermentation procedures. After the equilibration time, which helps to reorganize the matrix structure solely due to the chemical characteristics of the sample (Purwandari et al., 2007), the viscosity was measured by means of a Brookfield® DV-I Prime rotational viscometer (Middleboro, MA, United States) equipped with a SC4-18 spindle. The temperature was maintained at 25.0 ± 0.5°C by connecting the small sample adapter chamber (Middleboro, MA, United States) to a thermostatic water bath. The viscometer was connected to a computer for the data acquisition at 1-s intervals in an ASCII table. Apparent viscosity () was measured between the range of shear rate from 0.792 to 7.920 s–1. The flow behavior of the samples was described by the Ostwald de Waele model (power law), Equation (1):

where σ is the shear stress (Pa), K is the consistency index (Pa⋅sn), is the shear rate (s–1), and n is the flow behavior index.

Moreover, the viscosity values were also compared among the different samples at a shear rate value of 3.96 s–1 (η3.96), which was the central point of the shear rate intervals evaluated.

The viscosity of the fermented milk samples was also measured by means of a brass Ford flow cup (Sacco Srl, Cadorago, Italy), with a capacity of 100 ml and an outflow opening diameter of 3 mm. Measurements were performed according to the standard ISO 2431 (International Standard Organization [ISO], 2019), with the following slight modifications. Because of the high viscosities showed by the fermented milk samples, it was decided to express Ford cup viscosity as gram of sample eluted in 1 min, instead of the time necessary for the elution of the total volume (100 ml). For the measurement, the Ford cup was filled with 100 ml of fermented milk, previously equilibrated at 25°C.

Determination of Water Holding Capacity of Fermented Milk

Water holding capacity (WHC) may be defined as the ability of the fermented milk to hold water. WHC of all the fermented milk samples at pH 4.5 were determined by the centrifugation method described by Li et al. (2014). Twenty grams of each fermented milk were centrifuged at 2,600 rpm for 15 min. The supernatants were collected and weighed, and WHC was calculated according to the following Equation (2):

where W1 is the weight of supernatant after centrifugation (g), and W2 is the weight of the fermented milk before centrifugation (g).

Quantification of Exopolysaccharides Produced in Fermented Milk

The procedure for isolation and purification of free EPS previously reported by Mende et al. (2012) and by Rimada and Abraham (2003) was used. After adding 0.7 ml 80% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and heating to 90°C for 15 min, fermented milk samples, when the pH reached the value of 4.5, were cooled in ice water and centrifuged (2,000 rpm, 20 min, 4°C) to remove cells and proteins. After neutralization of the supernatant with NaOH, the EPS were purified following the procedure previously reported (Rimada and Abraham, 2003), and the quantification of the polymers was determined as polymer dry mass (Van Geel-Schutten et al., 1999). Samples were centrifuged (20 min at 2,600 rpm), and the pellets were air dried into an oven at 55°C. Dried EPS were weighted using an Acculab Precision Analytical Balances (Bradford, MA, United States) with four decimal places.

Statistical Analysis

For each parameter considered, one-way ANOVA and Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc tests (α = 0.05) were performed to detect significant differences among the different analysis performed for each strain. Data of each parameter considered were obtained from two independent fermentation processes, and each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The degree of correlation for the parameters measured was checked by means of Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r); the correlation was considered significant considering an α = 0.05.

Results

EPS Characterization

extracellular polysaccharides produced by W4451 has been characterized in terms of monosaccharides relative composition by GC-MS analysis and compared with those produced by the two Ld. bulgaricus strains (Table 1). Glucose, rhamnose, and mannose were present to a different extent in the EPS produced by both Ld. bulgaricus strains. Ldb2214 EPS was characterized by the presence of glucose as the main monosaccharide (90.0 ± 8.0%), while Ldb147 EPS was mainly made of galactose (48.2 ± 4.3%) and glucose (42.2 ± 3.8%). Even if in low amount, ribose was detected only in Ldb147 EPS. W4451 EPS resulted to be an HePS made of ∼50% glucose and rhamnose, with galactose mannose and ribose as the remaining part. Interestingly, W4451 EPS residual monosaccharides composition was similar to the EPS from Ldb147.

TABLE 1.

Monosaccharides composition of EPS, reported as relative percentage.

| Monosaccharide | Relative percentage of composition and SD |

||

| Weissella | Lb. delbrueckii subsp. | Lb. delbrueckii subsp. | |

| 4451 | bulgaricus 2214 | bulgaricus 147 | |

| Rhamnose | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| Ribose | 0.5 ± 0.5 | Nd | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Mannose | 12.6 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.5 |

| Galactose | 17.5 ± 1.6 | Nd | 48.2 ± 4.3 |

| Glucose | 57.0 ± 5.1 | 90.0 ± 8.0 | 42.2 ± 3.8 |

SD, standard deviation; Nd, not detected.

Skim Milk Fermentation

To evaluate the effect of EPS on milk rheological characteristics, the EPS+ strains (W4451, Ldb2214, and Ldb147) were cultivated in SSM at 37°C. As a negative control, the EPS− strain (Ll220) was incubated in SSM at 30°C.

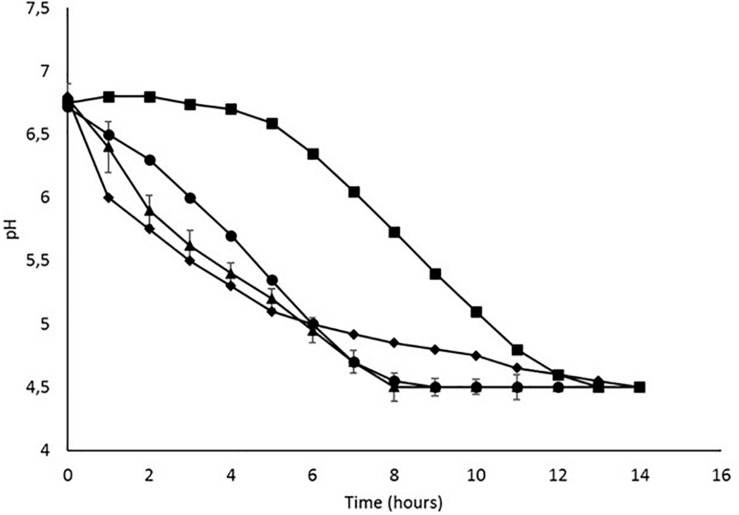

pH was measured over time for all the strains until the value of 4.5 was reached (Figure 1). The acidification time was different depending on the strains: Ldb147 was initially the faster acidifying strain but reached the pH of 4.5 only after 13 h. Ldb2214 showed a gradual decrease, reaching pH 4.5 in 9 h, while W4451 was the faster acidifying strain as it reached pH 4.5 in 8 h. The negative control, Ll220, begin to acidify milk after 4–5 h, reaching pH 4.5 only after 12 h.

FIGURE 1.

Batch fermentation profile of (●) Ld. bulgaricus 2214, ( ) Ld. bulgaricus 147, (

) Ld. bulgaricus 147, ( ) W. minor 4451, and (

) W. minor 4451, and ( ) Lc. lactis 220, in SSM.

) Lc. lactis 220, in SSM.

Exopolysaccharides Production and Viscosity of Fermented Milks

When pH 4.5 was reached, significantly different concentrations of EPS, varying from 1.88 g/L for Ldb2214 to 0.96 g/L for Ldb147, were found (Table 2). A very low concentration of polymers dry mass was found also for the EPS− strain Ll220, probably as a drawback of the EPS extraction method (Rimada and Abraham, 2003). W4451 was able to produce a concentration of EPS in milk of 1.58 g/L, a little smaller than Ldb2214.

TABLE 2.

Exopolysaccharides production (PDM), viscosity (measured by mean of Ford cup and viscometer) and water holding capacity in milk fermented by EPS producers Weissella 4451 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 147 and 2214 and negative control EPS-Lactococcus lactis 220.

| Strains | EPS production |

Viscosity |

Water holding capacity |

|||

| Ford cup |

Viscometer |

|||||

| PDM g/L | g/min | n (−) | K(Pa⋅sn) | η3.96 (Pa⋅s) | WHC (%) | |

| Weissella 4451 | 1.58b | 0.64b | 0.578a | 0.844b | 0.500b | 41.59b |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 147 | 0.96c | 1.22a | 0.353c | 0.863b | 0.349c | 37.72c |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 2214 | 1.88a | 0.34d | 0.553ab | 1.182a | 0.667a | 51.88a |

| Lactococcus lactis 220 | 0.21d | 3.24c | 0.435bc | 0.492c | 0.222d | 35.28d |

Data were obtained from two independent fermentation processes, and each sample was analyzed in triplicate. a–dValues (mean of the triplicate) followed by different letters within the same column are significantly different (Tukey’s honestly significant difference, p < 0.05). PDM, polymer dry mass; n (-), flow behavior index; K (Pa⋅sn), consistency index; η3.96 (Pa⋅s), apparent viscosity; WHC, water holding capacity.

Considering the high EPS concentration observed for the EPS+ strains, the rheological behavior of fermented milks was measured to evaluate, in particular, the ability of W4451 to modify milk’s viscosity in comparison to the other strains considered. The obtained rheological data from flow curves (shear rate vs. shear stress) were well fitted by the power law model, showing high determination coefficients (R2 = 0.94–0.99). All fermented milks showed a pseudoplastic, shear-thinning behavior (Table 2), as the apparent viscosity strongly decreased with the increase in shear rate (Hess et al., 1997). Values of flow behavior indices (n) varied from 0.353 ± 0.112 for Ldb147, which was characterized by the most pseudoplastic behavior, to 0.578 ± 0.071 for W4451.

K coefficient indices, which indicate the consistency of the coagulum at a low shear rate (1 s–1), showed significant differences (p < 0.05) that were related to the differences in apparent viscosity values (η3.96) for Ldb2214 and Ll220; on the contrary, K index did not exhibit a significant variation for Ldb147 and W4451 while having a different η3.96 value.

This observation can be explained by the different flow behavior between Ldb147 and W4451 that is observable by the reported η values. However, W4451, together with Ldb2214, was the best EPS producer and showed also significantly higher values of apparent viscosity of the fermented milk when compared with Ldb147 and the EPS− Ll220 (+ 30.2 and + 55.6% of η3.96 values, respectively). In particular, Ldb2214 showed the highest value of consistency index and apparent viscosity (K = 1.182 Pa⋅sn, η3.96 = 0.667 Pa⋅s) (p < 0.05), resulting in a thicker and firmer structure (Table 2).

With the application of a viscometer, it is possible to measure the dynamic viscosity and the shear-dependent, flow behavior of the fluid; however, this instrument could not be practical and affordable in the case of small or medium-sized dairies. Several faster and internal quality control-oriented methods exist such as Ford cup method. Ford cup is less expensive than a common viscometer; it does not need maintenance or specific extra tools (e.g., specific spindles and cups).

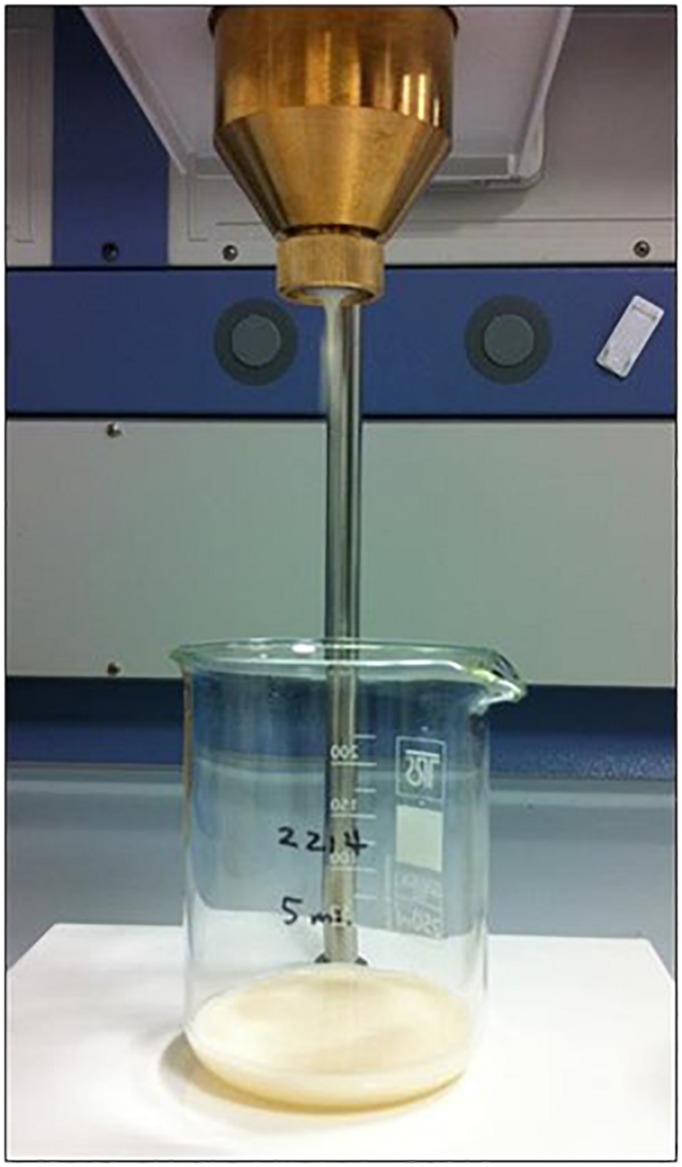

With the intention to propose an easy and less-expensive method than rotational viscometer to evaluate and monitor milk gelation, the viscosity of fermented milks, expressed as flowrate (g/min), was measured also by weighing the milk flowing through a Ford cup (Han et al., 2016) in a fixed time (Figure 2). Milk fermented by EPS− Ll220 showed the highest flowrate, resulting as the less viscous sample, while W4451 produced, together with Ldb2214, the most viscous sample (Table 2). Ford cup data were in sufficient agreement (r = 0.85, p < 0.001) with the apparent viscosity measured using the viscometer, allowing the discrimination between the strains (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Ford cup used to measure the viscosity of fermented milk by weighing the milk flowing through an orifice of 3 mm diameter.

Water Holding Capacity Measurement

The results of the WHC measurements (Table 2) showed different behaviors between strains EPS+ and EPS−; in particular, the milk fermented by the EPS− strain was significantly more susceptible to syneresis (p < 0.05) compared to the EPS+ fermented milk samples. Whey retention was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in milk fermented by W4451 than by Ldb147 (EPS+) and Ll220 (EPS−). As expected, the strain Ldb2214, which was the best EPS producer, showed the highest (p < 0.05) WHC value. The milk fermented by this strain resulted also in more viscosity.

Discussion

Weissella minor strain (W4451), analyzed in the present work, isolated from sourdough, was able to ferment SSM by consuming lactose as carbon source and to reach the final pH of 4.5 faster than two dairy isolates Ldb2214 and Ldb147. The frequent presence of Weissella strains in different fermented products suggest their ability to adapt to different environment and different sugars availability (Abriouel et al., 2015). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no specific literature data on W. minor ability to ferment milk, but at the same time, some data are available about the inability W. confusa and Weissella cibaria to use lactose and galactose (Quattrini et al., 2019). In our study, when fermentation was stopped, W4451 was able to produce HePS similarly to other LAB strains such as Ldb2214 and Ldb147, although the EPS produced were different either for the monosaccharides composition or percentage of the repeating units (Table 1). These results were in agreement with the previously observed structural diversity of EPS produced by LAB (Zeidan et al., 2017), confirming that galactose and glucose, and to a lesser extent mannose and rhamnose, are the most frequently occurring sugars in EPS produced by lactobacilli.

The EPS produced by W4451 were characterized by a composition similar to the HePS produced by W. cibaria (Adesulu-Dahunsi et al., 2018) but different from other Weissella species’ EPS (Bejar et al., 2013; Adesulu-Dahunsi et al., 2018).

When cultivated in SSM, W5541 turned out to be the fastest acidifying strain, if compared to Ll220 Ldb2214, and Ldb147, which were previously shown to have variable, strain-dependent, acidification attitudes (Bancalari et al., 2016). This result is in agreement with the work of Fessard and Remize (2017), who found Weissella spp. to have an acidifying capacity similar to Lactobacillus or Leuconostoc in food fermentations. As the pH can affect the viscosity of fermented milks by modifying the structure and the interactions among caseins (Schkoda et al., 1999), the permeability of the gels (Lee and Lucey, 2004), the WHC, and potentially EPS breakage (Pham et al., 2000); the fermentations were stopped at pH 4.5 by rapid cooling at 4°C.

At the end of SSM fermentation (pH 4.5), it was possible to observe differences in the appearance of milks fermented by the EPS+ strains. W4451 produced a more compact and uniform clot, similarly to Ldb2214. Differently, Ldb147 produced a grainier and looser clot similarly to EPS− strain Ll220 (data not shown). The different appearance of the clots may be related to the different EPS composition, as previously observed (Vincent et al., 2001).

Significantly different amounts of EPS were present after milk fermentation, varying from 1.88 g/L for Ldb2214 to 0.96 g/L for Ldb147 (Table 2). On the other hand, it is known that the amount and effect of EPS synthesized in situ can vary considerably, depending on the strain, substrate, and fermentation conditions (Mende et al., 2013).

Noteworthy, W4451, originally isolated from a non-dairy matrix, produced just a slightly smaller concentration of EPS as compared to Ldb2214, one of the species more frequently used to produce yogurt and the majority of fermented milks (Kafsi Hela et al., 2014). Considering that EPS production can be accompanied by a variation in the apparent viscosity of the medium (Mende et al., 2013), the ability of W4451 to modify milk’s gel structure and rheology was evaluated and compared to the other strains behaviors.

W4451 and Ldb2214 strains produced fermented milks with a lower shear rate dependence than the other evaluated LAB strains. The relatively low structured gel behaviors could be related to differences in terms of molecular weight of the produced EPS, as strong differences in terms of EPS composition were not highlighted. In fact, it has been reported that polysaccharides characterized by higher molecular weights can promote a more pronounced shear thinning behavior (Cui et al., 1994; Kafsi Hela et al., 2014).

As previously reported for other LAB (Ayala-Hernández et al., 2009) and Weissella species (Benhouna et al., 2019) also EPS produced by W4451 and Ldb2214 showed good technological and rheological properties that are mainly related to the interaction between milk proteins and polysaccharides. Differently from Benhouna et al. (2019), who used extracted EPS by W. confusa as an additive able to improve viscosity of milk gels acidified by glucono delta-lactone, we have demonstrated the ability of a W. minor strain to acidify milk and produce EPS in situ.

Other authors observed that EPS produced by different LAB strains could be characterized by different composition and structure, and this can greatly influence the ability of EPS to interact with milk proteins and modify rheology of fermented milks, by increasing or decreasing viscosity (Purohit et al., 2009; Sodini et al., 2010). In our study, a different chemical composition of EPS produced by the strains was observed, but this probably influence milk viscosity less than the EPS concentration; in fact, the amount of produced EPS by W. minor and the two Ld. bulgaricus strains was directly correlated (r = 0.93, p < 0.001) with the measured apparent viscosity and WHC (r = 0.87, p < 0.001) of fermented milks (Table 2).

These findings are in agreement with what were reported by other authors, in the case of W. confusa (Benhouna et al., 2019) and Streptococcus thermophilus (Mende et al., 2013). However, it should be pointed out that other authors observed also a different trend, with viscosity decrease at high concentrations of EPS (Marshall and Rawson, 1999; Sodini et al., 2010). These opposite trends can be justified by molecular differences and structure of EPS (e.g., capsular and ropy EPS, type and density of the charges present on the molecules and their interactions with caseins, etc.) (Purwandari et al., 2007; Corredig et al., 2011), as the texturizing effect is strain dependent and specific (Sodini et al., 2010).

To confirm that the changes in milk rheological properties were mainly caused by the production of EPS, it is important to observe that the EPS− Ll220 produced the fermented milk with the lowest apparent viscosity and consistency index, in accordance to previous observations (Hassan et al., 2003).

The best EPS-producing strains showed also the highest WHC values and produced the most viscous fermented milks. These results confirmed that WHC and physical stability are also in relation with the presence and the amount of EPS produced, which improves the stability against whey syneresis (Han et al., 2016).

The ability of W4451 EPS to limit syneresis in fermented milk is in agreement with recent observation (Purohit et al., 2009; Benhouna et al., 2019), and it is of central importance because the syneresis of yogurt-like products is delayed and limited during shelf-life by EPS interaction with the free water in the gel-like structure (Guzel-Seydim et al., 2005; Okoth et al., 2011).

In conclusion, W. minor wild-strain W4451, previously isolated from sourdough, was able to acidify milk, produce EPS in situ, and increase viscosity of the final product. This ability was comparable to that of two Ld. bulgaricus strains, commonly used to acidify milk and to produce EPS. Thus, the wild-strain W. minor W4451 may represent a good candidate to be used as starter in milk fermentation. The ability of W4451 to modify the viscosity of the gel could be measured also using the Ford cup. The Ford cup turned out to be a useful and simple method to control fermented milk viscosity by small- or medium-sized dairies.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

EB: project design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting. MA: project design, analysis, and data interpretation. BB: manuscript drafting and critical revision. AC: contribution to the chemical analysis. GM: critical revision and finalization of the manuscript. MG: data interpretation, critical revision, and finalization of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Regione Emilia-Romagna (Italy) in the framework of the project “Collezioni microbiche regionali: la biodiversità al servizio dell’industria agroalimentare” (CUP J12F16000010009).

References

- Abriouel H., Lerma L. L., Casado Muñoz M. C., Montoro B. P., Kabisch J., Pichner R., et al. (2015). The controversial nature of the Weissella genus: technological and functional aspects versus whole genome analysis-based pathogenic potential for their application in food and health. Front. Microbiol. 6:1197. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adesulu-Dahunsi A. T., Sanni A. I., Jeyaram K. (2018). Production, characterization and in vitroantioxidant activities of exopolysaccharide from Weissella cibaria GA44. J. Food Sci. Technol. 87 432–442. 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.09.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aslim B., Yüksekdag Z. N., Beyatli Y. (2005). Exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus strains under different growth conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21:673. 10.1007/s11274-004-3613-2 11097906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Hernández I., Hassan A. N., Goff H. D., Corredig M. (2009). Effect of protein supplementation on the rheological characteristics of milk permeates fermented with exopolysaccharide-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Food Hydrocoll. 23 1299–1304. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bancalari E., Bernini V., Bottari B., Neviani E., Gatti M. (2016). Application of impedance microbiology for evaluating potential acidifying performances of starter lactic acid bacteria to employ in milk transformation. Front. Microbiol. 7:1628. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar W., Gabrie V., Amari M., Morelcde S., Mezghania M., Maguinfg E., et al. (2013). Characterization of glucansucrase and dextran from Weissella sp. TN610 with potential as safe food additives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 52 125–132. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhouna I. S., Heumann A., Rieu A., Guzzo J., Kihal M., Bettache G., et al. (2019). Exopolysaccharide produced by Weissella confusa: chemical characterisation, rheology and bioactivity. Int. Dairy J. 90 88–94. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2018.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. D., Samelis J., Metaxopoulos J., Wallbanks S. (1993). Taxonomic studies on some leuconostoc-like organisms from fermented sausages: description of a new genus Weissella for the Leuconostoc paramesenteroides group of species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 75 595–603. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb01600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corredig M., Sharafbafi N., Kristo E. (2011). Polysaccharide-protein interactions in dairy matrices, control and design of structures. Food Hydrocoll. 25 1833–1841. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W., Mazza G., Biliaderis C. G. (1994). Chemical structure, molecular size distributions, and rheological properties of flaxseed gum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42 1891–1895. 10.1021/jf00045a012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cupi D., Elvig-Jorgensen S. G. (2019). Safety assessment of Weissella confusa – A direct-fed microbial candidate. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 107:104414. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessard A., Remize F. (2017). Why Are Weissella spp. not used as commercial starter cultures for food fermentation? a review. Fermentation 3:38 10.3390/fermentation3030038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galle S., Arendt E. K. (2014). Exopolysaccharides from sourdough lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 7 891–901. 10.1080/10408398.2011.617474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomathi S., Sasikumar P., Murugan K., Selvi M. S., Selvam G. S. (2014). Screening of indigenous oxalate degrading lactic acid bacteria from human faeces and south indian fermented foods: assessment of probiotic potential. Sci. World J. 2014:648059. 10.1155/2014/648059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzel-Seydim Z. B., Sezgin E., Seydim A. C. (2005). Influences of exopolysaccharide producing cultures on the quality of plain set type yogurt. Food Control 16 205–209. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2004.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Yang Z., Jing X., Yu P., Zhang Y., Yi H., et al. (2016). Improvement of the texture of yogurt by use of Exopolysaccharide producing lactic acid Bacteria. Bio. Med. Res. 2016:7945675. 10.1155/2016/7945675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A. N., Ipsen R., Janzen T., Qvist K. B. (2003). Microstructure and rheology of yogurt made with cultures differing only in their ability to produce Exopolysaccharides. J. Dairy Sci. 85 1632–1638. 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(03)73748-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess S. J., Roberts R. F., Ziegler G. R. (1997). Rheological properties of nonfat yogurt stabilized using Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus producing exopolysaccharide or using commercial stabilizer systems. J. Dairy Sci. 80 252–263. 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(97)75933-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Standard Organization [ISO] (2019). Paints and Varnishes Determination of Flow Time by Use of Flow Cups. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/73851.html [accessed July 26, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Kafsi Hela E. I., Binesse J., Loux V., Buratti J., Boudebbouze S., Dervyn R., et al. (2014). Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. lactis and ssp. bulgaricus: a chronicle of evolution in action. BMC Genom. 15:407. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M. S., Lim H. S., Kim S. M., Lee H. C., Oh J. S. (2011). Effect of Weissella cibaria on Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced Interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production in KB Cells. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 41 9–18. 10.4167/jbv.2011.41.1.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasam K. M. G. M. M., Jeewanthi R. K. C., Lee N. K., Paik H. D. (2019). Characterization of cottage cheese using Weissella cibaria D30: physicochemical, antioxidant, and antilisterial properties. J. Dairy Sci. 102 3887–3893. 10.3168/jds.2018-15360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel S. A., Roberts R. F. (1998). Development of a growth medium suitable for exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus RR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 40 87–92. 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto-Nira H., Aoki R., Mizumachi K., Sasaki K., Naito H., Sawada T., et al. (2011). Interaction between Lactococcus lactis and Lactococcus raffinolactis during growth in milk: development of a new starter culture. J. Dairy Sci. 95 2176–2185. 10.3168/jds.2011-4824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. W., Park J. Y., Jeong H. R., Heo H. J., Han N. S., Kim J. H. (2012). Probiotic properties of Weissella strains isolated from human faeces. Anaerobe 18 96–102. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. J., Lucey J. A. (2004). Structure and physical properties of yogurt gels: effect of inoculation rate and incubation temperature. J. Dairy Sci. 87 3153–3164. 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(04)73450-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li W., Chen X., Feng M., Rui X., Jiang M., et al. (2014). Microbiological, physicochemical and rheological properties of fermented soymilk produced with exopolysaccharide (EPS) producing lactic acid bacteria strains. J. Food Sci. Technol. 57 477–485. 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.02.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Zhang Z., Qiu L., Zhang F., Xu X., Wei H., et al. (2016). Characterization and bioactivities of the exopolysaccharide from a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus plantarum WLPL04. J. Dairy Sci. 100 6895–6905. 10.3168/jds.2016-11944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch K. M., Mc Sweeney P. L. H., Arendt E. K., Uniacke-Lowe T., Galle S., Coffey A. (2014). Isolation and characterisation of exopolysaccharide-producing Weissella and Lactobacillus and their application as adjunct cultures in cheddar cheese. Int. Dairy J. 34 125–134. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2013.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malang S. K., Maina N. H., Schwab C., Tenkanen M., Lacroix C. (2015). Characterization of exopolysaccharide and ropy capsular polysaccharide formation by Weissella. Food Microbiol. 46 418–427. 10.1016/j.fm.2014.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall V. M., Rawson H. L. (1999). Effects of exopolysaccharide- producing strains of thermophilic lactic acid bacteria on the texture of stirred yogurt. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 34 137–143. 10.1046/j.1365-2621.1999.00245.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mende S., Mentner C., Thomas S., Rohm H., Jaros D. (2012). Exopolysaccharide production by three different strains of Streptococcus thermophilus and its effect on physical properties of acidified milk. Eng. Life Sci. 12 466–474. 10.1002/elsc.201100114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mende S., Peter M., Bartels K., Rohm H., Jaros D. (2013). Addition of purified exopolysaccharide isolates from S. thermophilus to milk and their impact on the rheology of acid gels. Food Hydrocoll. 32 178–185. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Maatsch J., Bencivenni M., Caligiani A., Tedeschi T., Bruggeman G., Bosch M., et al. (2016). Pectin content and composition from different food waste streams. Food Chem. 201 37–45. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. T., Razafindralambo H., Blecker C., N’Yapo C., Thonart P., Delvigne F. (2014). Stochastic exposure to sub-lethal high temperature enhances exopolysaccharides (EPS) excretion and improves Bifidobacterium bifidum cell survival to freeze–drying. Biochem. Eng. J. 88 85–94. 10.1016/j.bej.2014.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okoth E. M., Kinyanjui P. K., Kinyuru J. N., Juma F. O. (2011). Effects of substituting skimmed milk powder with modified starch in yoghurt production. J. Agric. Sci. Tech. 13 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oleksy M., Klewicka E. (2016). Exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus sp. –biosynthesis and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 58 450–462. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1187112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham P. L., Dupont I., Roy D., Lapointe G., Cerning J. (2000). Production of Exopolysaccharide by Lactobacillus rhamnosus R and analysis of Its enzymatic degradation during prolonged fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 2302–2310. 10.1128/aem.66.6.2302-2310.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit D. H., Hassan A. N., Bhatia E., Zhang X., Dwivedi C. (2009). Rheological, sensorial, and chemopreventive properties of milk fermented with exopolysaccharide-producing lactic cultures. J. Dairy Sci. 92 847–856. 10.3168/jds.2008-1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purwandari U., Shaha N. P., Vasiljevicab T. (2007). Effects of exopolysaccharide-producing strains of Streptococcus thermophilus on technological and rheological properties of set-type yoghurt. Int. Dairy J. 17 1344–1352. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.01.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrini M., Korcari D., Ricci G., Fortina M. G. (2019). A polyphasic approach to characterize Weissella cibaria and Weissella confusa strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimada P. S., Abraham A. G. (2003). Comparative study of different methodologies to determine the exopolysaccharide produced by kefir grains in milk and whey. Lait 83 79–87. 10.1051/lait:2002051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruas-Madiedo P., Hugenholtz J., Zoon P. (2002). An overview of the functionality of exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 12 163–171. 10.1016/s0958-6946(01)00160-1 12647947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanlibaba P., Çakmak G. A. (2016). Exopolysaccharides production by lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100 3877–3886. 10.4172/2471-9315.1000115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiraldi C., Valli V., Molinaro A. (2006). Exopolysaccharides production in Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Lactobacillus casei exploiting microfiltration. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33:384. 10.1007/s10295-005-0068-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schkoda P., Hechler A., Kessler H. G. (1999). Effect of minerals and pH on rheological properties and syneresis of milk-based acid gels. Int. Dairy J. 9 269–274. 10.1016/s0958-6946(99)00073-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sodini I., Remeuf F., Haddad S., Corrieu G., Sodini I., Remeuf F., et al. (2010). The relative effect of milk base, starter, and process on yogurt texture: a review the relative effect of milk base, starter, and process on yogurt texture: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 44 113–137. 10.1080/10408690490424793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturino J. M. (2018). Literature-based safety assessment of an agriculture- and animal-associated microorganism: Weissella confusa. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 95 142–152. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torino M. I., Font de Valdez G., Mozzi F. (2015). Biopolymers from lactic acid bacteria. Novel applications in foods and beverages. Front. Microbiol. 6:834. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2009). Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. HHS Publication No. (CDC). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/labs/pdf/CDC-BiosafetyMicrobiologicalBiomedicalLaboratories-2009-P.PDF [accessed July 26, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Van Geel-Schutten G. H., Faber E. J., Smit E., Bonting K., Smith M. R., Ten Brink B., et al. (1999). Biochemical and structural characterization of the glucan and fructan exopolysaccharides synthesized by the Lactobacillus reuteri wild-type strain and by mutant strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 3008–3014. 10.1128/aem.65.7.3008-3014.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent S. J. F., Faber E. J., Neeser J. R., Stingele F., Kamerling J. P. (2001). Structure and properties of the exopolysaccharide produced by Streptococcus macedonicus Sc136. Glycobiology 11 131–139. 10.1093/glycob/11.2.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannini E., Waters D. M., Coffey A., Arendt E. K. (2015). Production, properties, and industrial food application of lactic acid bacteria-derived exopolysaccharides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 1121–1135. 10.1007/s00253-015-7172-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan A. A., Poulsen V. K., Janzen T., Buldo P., Derkx P. M. F., Oregaard G., et al. (2017). Polysaccharides production by lactic acid bacteria: from genes to industrial applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41 168–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Peng X., Zhang N., Liu L., Wang Y., Ou S. (2014). Cytotoxicity comparison of quercetin and its metabolites from in vitro fermentation of several gut bacteria. Food Funct. 5 2152–2156. 10.1039/c4fo00418c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.