Abstract

Sulfonamide-class antibiotics are recognized as water pollutants, which have negative environmental impacts. A strategy to deal with sulfonamides is throughout the application of oxidation processes. This work presents the treatment of the sulfacetamide (SAM) antibiotic by electrochemical oxidation, UV-C/H2O2 and photo-Fenton process. It was established the main degradation routes during each process action. A DFT computational analysis for SAM structure was done and mass spectra of primary transformation products were determined. Chemical oxygen demand (COD), total organic carbon (TOC) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) were also followed. Additionally, SAM treatment in simulated seawater and hospital wastewater was measured. These data can be useful for comparative purposes about degradation of sulfonamide-class antibiotics by electrochemical and advanced oxidation processes.

Keywords: Antibiotics degradation, Degradation routes, DFT analysis, Matrix effects, Treatment extent

Specifications Table

| Subject | Environmental chemistry, Chemical Engineering |

| Specific subject area | Electrochemical and advanced oxidation processes |

| Type of data | Table Figure Picture |

| How data were acquired | Data were acquired by using HPLC, HPLC-MS and Gaussian software |

| Data format | Raw Analyzed |

| Parameters for data collection | The experimental tests were developed at fixed conditions to evaluate the ability of processes to eliminate a representative sulfonamide antibiotic |

| Description of data collection | All experimental data were obtained at lab-scale |

| Data source location | Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor de Antioquia (IUCMA), Universidad de Antioquia and Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia |

| Data accessibility | Mendeley data repository through the following link: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bctc4dh2ck/draft?a=cd8f77df-08f8-45d9-ae48-1f9f8186ac9c |

Value of the Data

|

1. Data description

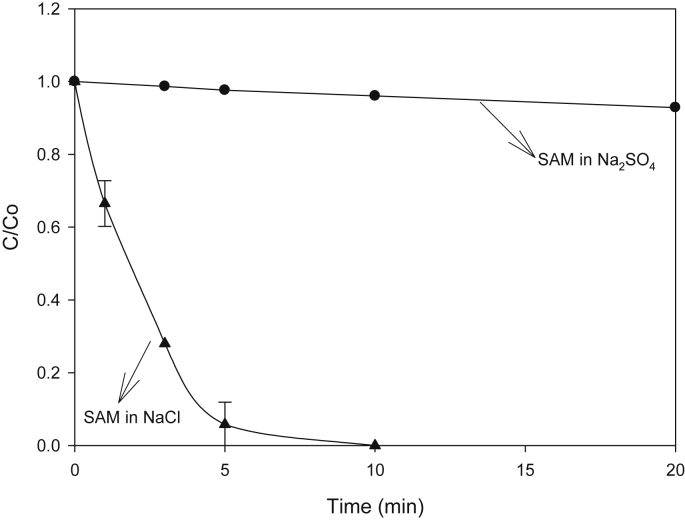

Information on the main degradation routes for sulfacetamide (SAM) treatment by the considered processes is initially presented. Such data are relevant to understand action of the systems on the antibiotics [1]. The considered electrochemical system is characterized by the action of active chlorine species as degrading agents (mediated route, Eqs (1), (2), (3), (4)), in NaCl presence. Meanwhile, when Na2SO4 is used as supporting electrolyte, oxidative species in solution bulk cannot be generated from sulfate ions, but oxidation on anode surface (direct route) can be evidenced [[2], [3], [4]]. Fig. 1A depicts degradation of the sulfonamide by electrochemical oxidation utilizing two supporting electrolytes (i.e., NaCl and Na2SO4) to identify the action routes of the system.

| Ti/IrO2(anode) + 2Cl− → Cl2 + 2e− | (1) |

| Cl2 + H2O → HOCl + HCl | (2) |

| HOCl + H2O → H3O+ + OCl− | (3) |

| Cl2, HOCl, OCl− + organic pollutant → degradation products | (4) |

Fig. 1.

Electrochemical treatment of SAM.

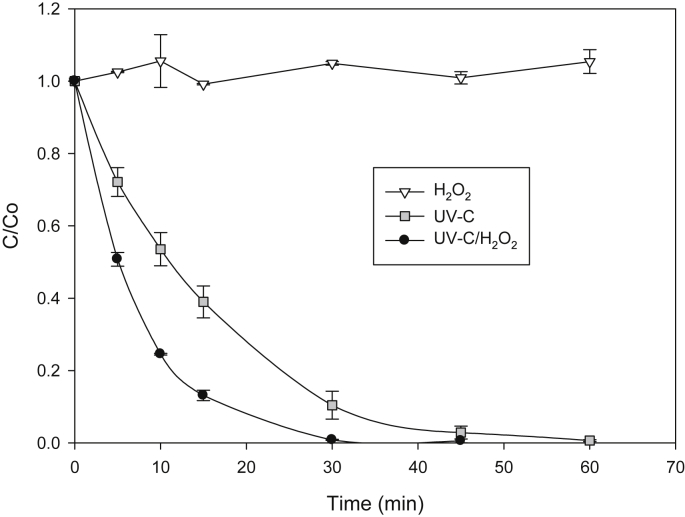

Fig. 2 presents evolution of SAM under UV-C irradiation, hydrogen peroxide and AOP UV-C/H2O2; this last system generates hydroxyl radical (Eq. (5)) as main degrading species (Eq. (6)) [5].

| UV-C + H2O2 → 2 HO• | (5) |

| HO• + organic pollutant → degradation products | (6) |

Fig. 2.

Degradation of SAM by UV-C/H2O2.

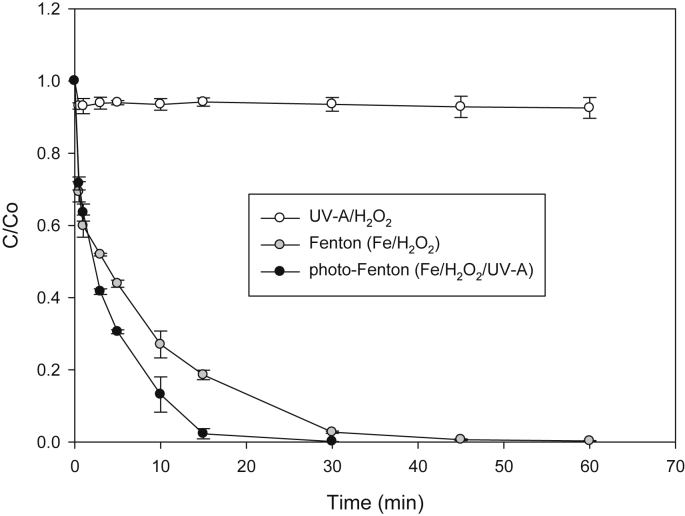

In Fig. 3 is shown SAM elimination by photo-Fenton system (which involves interaction of iron ions with hydrogen peroxide and light to produce HO•, Eqs. (7), (8) [6]). Control experiments (i.e., UV-A/H2O2 and Fenton) are also presented in Fig. 3.

| Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + HO• + HO− | (7) |

| Fe3+ + H2O + hν(UV–vis) → Fe2+ + HO• + H+ | (8) |

Fig. 3.

Evolution of SAM during treatment by photo-Fenton.

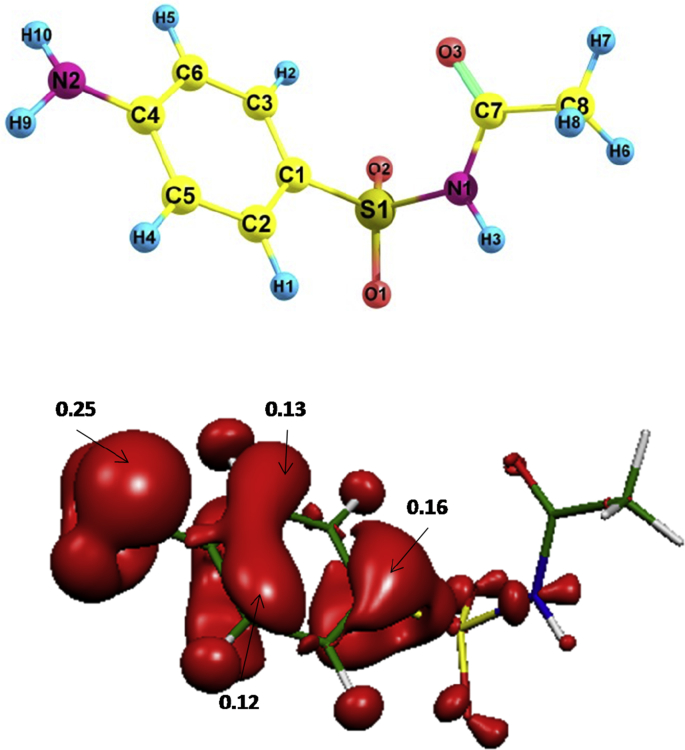

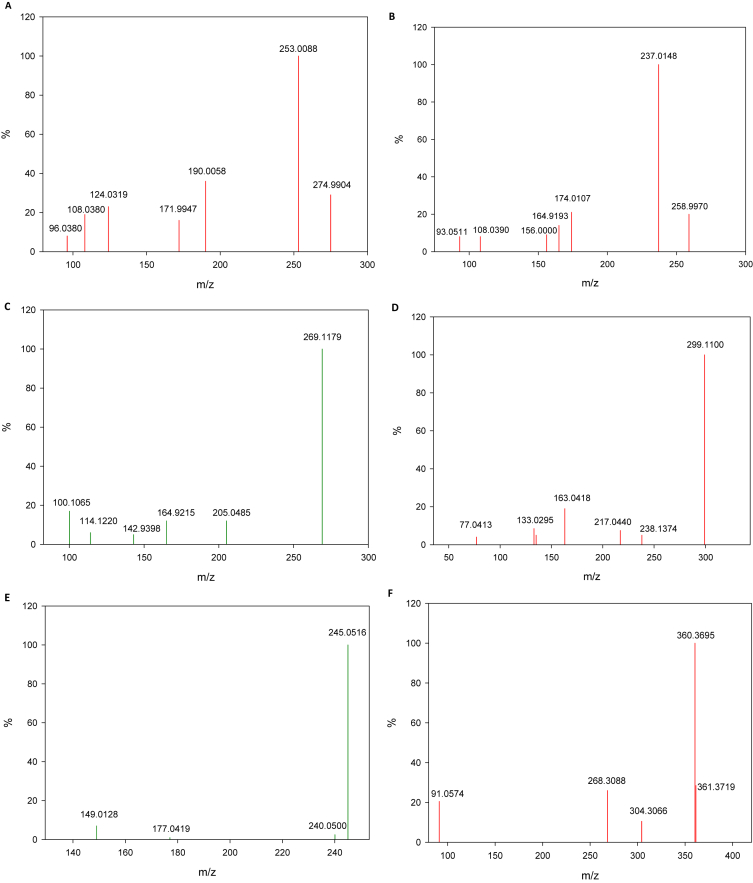

Degradation of SAM under the oxidation processes can be promoted by active chlorine (e.g., electrochemistry) or hydroxyl radical (e.g., photo-Fenton and UV-C/H2O2). These are electrophilic species able to attack electron rich moieties [1,4]. Then, computational calculations to identify regions on SAM with high electron density and susceptible to attacks by such degrading agents was carried (Fig. 4). Additionally, to determine the primary transformations, analyses of HPLC-MS were performed. Table 1 summarizes the primary products found for SAM treatment by each process; whereas, Fig. 5 contains mass spectra of the transformation products.

Fig. 4.

Electron density regions on SAM more susceptible to attacks by electrophilic species (e.g., HOCl or HO•).

Table 1.

Summary of primary products found for SAM treatment by the considered processes.

| Product [M+H]+ (Mass spectrum inFig. 5) |

Process |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical oxidation | UV-C alone | UV-C/H2O2 | Photo-Fenton | |

| 275 (A) | X | |||

| 259 (B) | X | X | X | X |

| 269 (C) | X | |||

| 299 (D) | X | X | ||

| 245 (E) | X | X | X | X |

| 360 (F) | X | |||

X means the product was found during degradation by the process.

Fig. 5.

Mass spectra of primary degradation products.

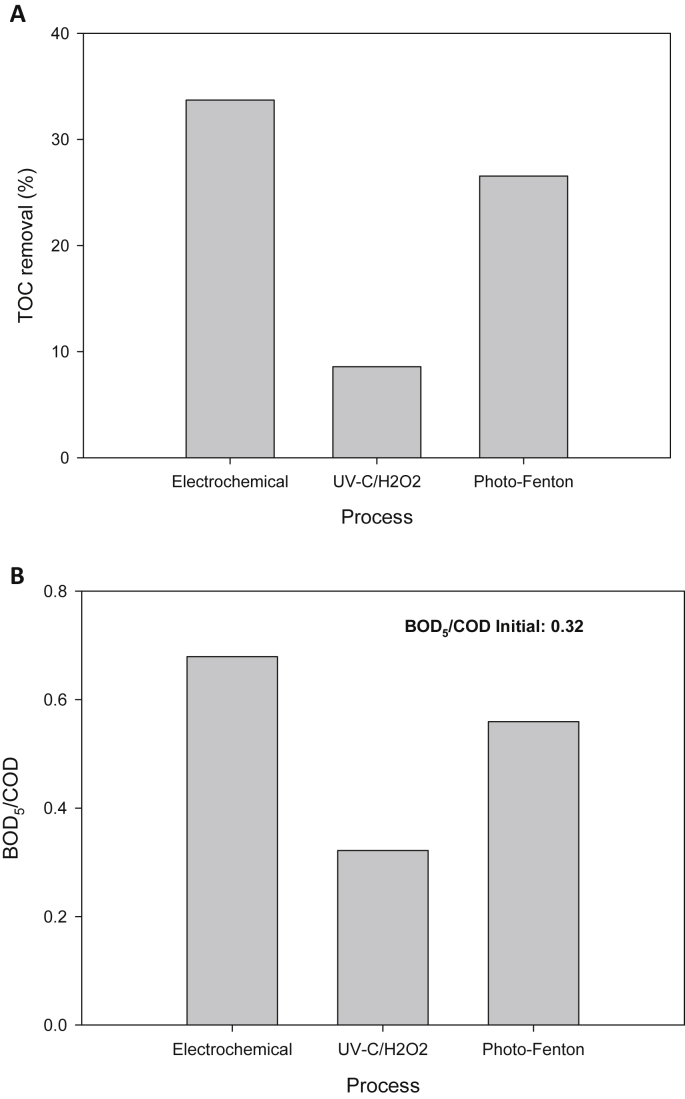

To establish the treatments extent, COD, TOC and BOD5 were measured at 100% of SAM degradation by each considered process. Fig. 6A illustrates the TOC removal, whereas Fig. 6B presents the biodegradability relationship (BOD5/COD).

Fig. 6.

Treatments extent.

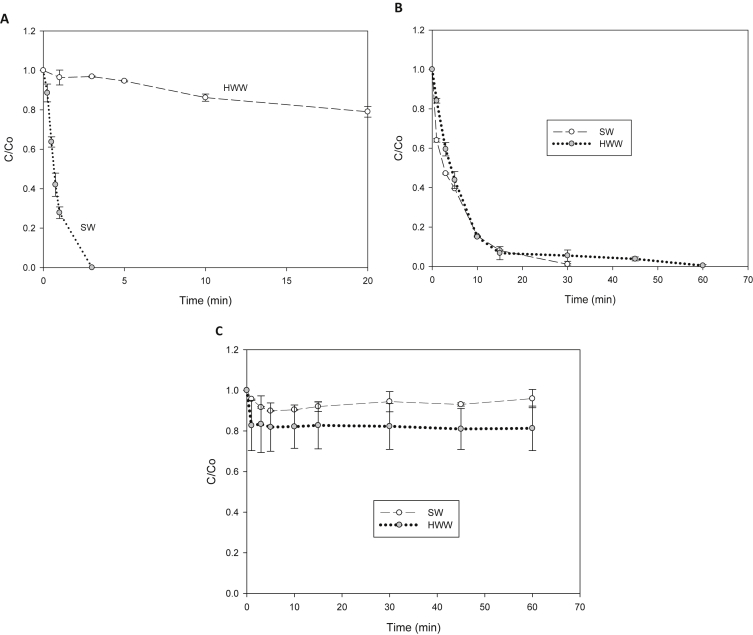

To test the ability of the processes to degrade the antibiotic in complex matrices, treatment of SAM in simulated seawater and hospital wastewater (see composition in Table 2) was performed. Fig. 7 shows the removal of SAM in these complex matrices during treatment by the three oxidation systems.

Table 2.

Composition of the complex matrices.

Fig. 7.

Degradation of SAM in simulated seawater (SW) and hospital wastewater (HWW) by the diverse processes. A. Electrochemistry. B. UV-C/H2O2. C. Photo-Fenton.

The raw data for the above figures and tables is available on the Mendeley data repository (see this link: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bctc4dh2ck/draft?a=cd8f77df-08f8-45d9-ae48-1f9f8186ac9c).

2. Experimental design, materials, and methods

2.1. Reagents

Sodium sulfacetamide was provided by Corpaul (Medellín, Colombia) Sodium chloride, calcium chloride dihydrate, potassium chloride, ammonium chloride, sodium sulfate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, urea and acetonitrile were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Urea was purchased from Carlo Erba (Sabadell, Spain) and formic acid was provided by Carlo-Erba (Val de Reuil, France). All chemicals were used as received. The solutions were prepared using distilled water.

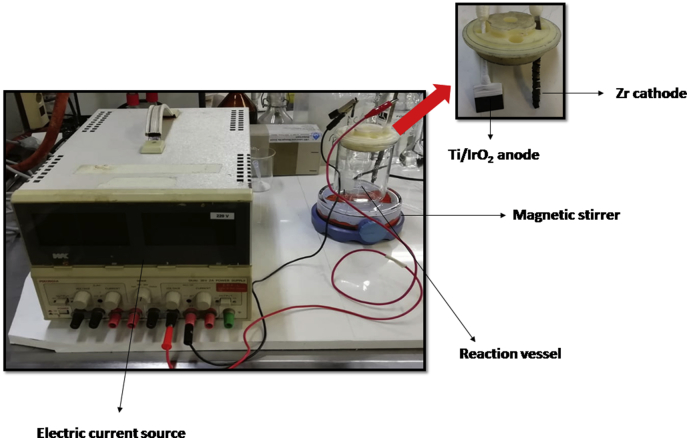

2.2. Reaction systems

An electrolytic cell equipped with a Ti/IrO2 rectangular plate of 8 cm2 (anode, previously characterized [9]), a zirconium spiral of 10 cm2 (cathode) and a WK electric apparatus (as current source) were used for the electrochemical experiments (Picture 1). A current density of 5 mA cm−2 and 0.05 mol L−1 of NaCl or Na2SO4 as supporting electrolyte were used. The electrochemical system was operated under constant stirring conditions. In the experiments, 150 mL of the antibiotic solutions were treated. Each experiment was performed at least by duplicate. During treatments, aliquots of 1.2 mL were taken at regular time intervals to perform the analyses of antibiotic evolution.

Picture 1.

Electrochemical reaction system.

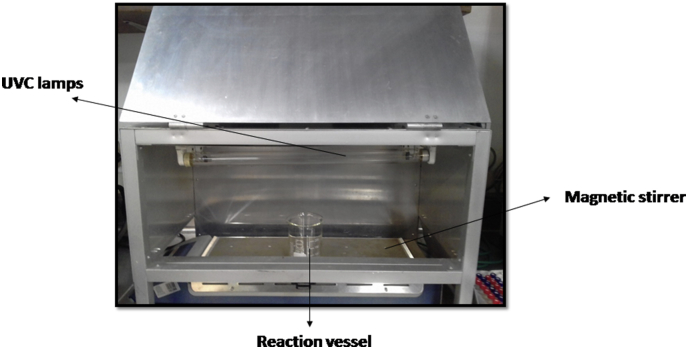

The photochemical processes were carried out in a homemade aluminum reflective reactor. In the case of UV-C/H2O2, the reaction system was equipped with 5 UV-C lamps (LUMEK T8 15W) with main emission at 254 nm (Picture 2). Antibiotic (40 μmol L−1) solutions (150mL) were placed in beakers under constant stirring. Each experiment was performed at least by duplicate. During treatments, until eight aliquots of 1.0 mL were taken at regular time intervals to perform the analyses.

Picture 2.

Reaction system for UV/PS process.

Meanwhile, for photo-Fenton process, the same homemade aluminum reflective reactor equipped with 5 lamps (LuxTech T8 15W) was utilized. SAM (40 μmol L−1) solution (150 mL) was placed in beakers under constant stirring. In the photo-Fenton process, 500 μmol L−1 and 45 μmol L−1 of H2O2 and Fe (II) respectively were used.

2.3. Analyses

The evolution of SAM during treatments was followed by sing a UHPLC Thermoscientific Dionex UltiMate 3000 instrument equipped with an Acclaim™ 120 RP C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm) and a diode array detector. The injection volume was 20 μL, and a mixture of acetonitrile/aqueous formic acid (10 mmol L−1, pH 3.0) 40/60% V/V was used as mobile phase. The UV detection was carried out at 257, 270, 280 and 290 nm. It must be indicated that all degradation experiments were carried out at least by duplicate.

The computational analysis was performed with the Fukui function by applying the framework of functional density theory (DFT). SAM structure was optimized with the B3LYP hybrid functional density [10], with the 6-31 + G* basis set and the continuous polarization model [11] using the dielectric constant for water. Thus, f- (i.e., electrophilic Fukui functions) values were calculated. For f-, a higher number is an indicator of a higher possibility of attack by electrophilic species.

The determination of primary transformation products was carried out at 50% of the antibiotic degradation. For such determination an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a quaternary solvent supply manager and a sampler manager coupled to an Xevo-G2-XS-Q-Tof, Mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray interface (Waters Corporation). A Restek C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm; 1.7 μm) was used with water (acidified by 0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile (ACN) as eluents. The flowrate was 0.5 mL min−1 at room temperature. The gradient was from 90/10% water/ACN until 2 min, then the gradient change to 75/25% to 3 min, in 3,5 min change again to 90/10% to 6 min.

ESI + positive ionization mode and a sensitivity analysis were used for MS Determination with an analysis range of 50–700 Da, with a scan time of 0.1 s and a delay between operations of 0.01 s, for an analysis time of 6 minutes. The collision energy ramp was 10–30 V and the cone voltage was 30 V.

Chemical oxygen demand (COD) was established according to the Standard Methods for Examination of Water and Wastewater (5220 D). The closed reflux colorimetric method was used. An aliquot of 2500 μL of sample was added to a digestion vessel containing 1500 μL of digestion solution (potassium dichromate in concentrated sulfuric acid) and 3500 μL of sulfuric acid reagent (silver sulfate in concentrated sulfuric acid). The digestion was performed at 140 °C during 2 hours in a Velp Thermo-reactor. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm in a Lab Scient UV-1100 spectrophotometer.

Biochemical oxygen demand at 5 days (BOD5) was carried out according to the Standard Methods for Examination of Water and Wastewater (5210 B) using an Oxitop respirometric system thermostatted at 20 °C. The volume added to the incubation bottle contained 270 mL (10% V/V was the inoculum and 90% V/V was the sample). Prior to analysis, the pH was adjusted to near neutrality using sodium hydroxide (1.0 M), and residual hydrogen peroxide or active chlorine species were eliminated using sodium bisulfite (0.1 M).

Total organic carbon (TOC) was measured using a Teledyne Tekmar TOC analyzer. This was determined by combustion with catalytic oxidation at 680 °C using high-purity oxygen gas at a flow rate of 190 mL min−1. The apparatus had a non-dispersive infrared detector. Calibration of the analyzer was attained with standard potassium hydrogen phthalate (99.5%) solution. The injection sample volume was 50 μL.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank to Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor de Antioquia for the financial supporting provided through project “Degradación del antibiótico Sulfacetamida como contaminante emergente a través de Tecnologías Avanzadas de Oxidación”. R. A. Torres-Palma thanks Universidad de Antioquia UdeA for the support provided to their research group through “PROGRAMA DE SOSTENIBILIDAD” and the financing from COLCIENCIAS through the project No. 111577757323. E. A. Serna-Galvis thanks COLCIENCIAS for his PhD fellowship during July 2015–June 2019 (Convocatoria 647 de 2014).

Contributor Information

Efraím A. Serna-Galvis, Email: efrain.serna@udea.edu.co.

Ricardo A. Torres-Palma, Email: ricardo.torres@udea.edu.co.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Serna-Galvis E.A., Silva-Agredo J., Giraldo A.L., Flórez O.A., Torres-Palma R.A. Comparison of route, mechanism and extent of treatment for the degradation of a β-lactam antibiotic by TiO2 photocatalysis, sonochemistry, electrochemistry and the photo-Fenton system. Chem. Eng. J. 2016;284:953–962. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirés I., Brillas E. Remediation of water pollution caused by pharmaceutical residues based on electrochemical separation and degradation technologies : a review. Environ. Int. 2012;40:212–229. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panizza M., Cerisola G. Direct and mediated anodic oxidation of organic pollutants. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:6541–6569. doi: 10.1021/cr9001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deborde M., von Gunten U. Reactions of chlorine with inorganic and organic compounds during water treatment-Kinetics and mechanisms: a critical review. Water Res. 2008;42:13–51. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De la Cruz N., Esquius L., Grandjean D., Magnet a., Tungler a., de Alencastro L.F., Pulgarín C. Degradation of emergent contaminants by UV, UV/H2O2 and neutral photo-Fenton at pilot scale in a domestic wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2013;47:5836–5845. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pignatello J.J., Oliveros E., Mackay A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the Fenton reaction and related chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;36:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonin V.S., Santos M.C., Garcia-segura S., Brillas E. Electrochemical incineration of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin in sulfate medium and synthetic urine matrix. Water Res. 2015;83:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serna-Galvis E.A., Montoya-Rodríguez D., Isaza-Pineda L., Ibáñez M., Hernández F., Moncayo-Lasso A., Torres-Palma R.A. Sonochemical degradation of antibiotics from representative classes-Considerations on structural effects, initial transformation products, antimicrobial activity and matrix. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;50:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera Calderon E. EPFL; 2008. Effectiveness Factor of Thin-Layer IrO2 Electrocatalyst: Influence of Catayst Loading and Electrode Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghavachari K. Perspective on “Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange”. Theor. Chem. Accounts. 1999:361–363. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomasi J., Mennucci B., Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3094. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]