Engineering leaves to accumulate oils induced unexpected changes to fatty acid flux through the leaf lipid metabolic network.

Abstract

The triacylglycerols (TAGs; i.e. oils) that accumulate in plants represent the most energy-dense form of biological carbon storage, and are used for food, fuels, and chemicals. The increasing human population and decreasing amount of arable land have amplified the need to produce plant oil more efficiently. Engineering plants to accumulate oils in vegetative tissues is a novel strategy, because most plants only accumulate large amounts of lipids in the seeds. Recently, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves were engineered to accumulate oil at 15% of dry weight due to a push (increased fatty acid synthesis)-and-pull (increased final step of TAG biosynthesis) engineering strategy. However, to accumulate both TAG and essential membrane lipids, fatty acid flux through nonengineered reactions of the endogenous metabolic network must also adapt, which is not evident from total oil analysis. To increase our understanding of endogenous leaf lipid metabolism and its ability to adapt to metabolic engineering, we utilized a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments to characterize the path of acyl flux in wild-type and transgenic oil-accumulating tobacco leaves. Acyl flux around the phosphatidylcholine acyl editing cycle was the largest acyl flux reaction in wild-type and engineered tobacco leaves. In oil-accumulating leaves, acyl flux into the eukaryotic pathway of glycerolipid assembly was enhanced at the expense of the prokaryotic pathway. However, a direct Kennedy pathway of TAG biosynthesis was not detected, as acyl flux through phosphatidylcholine preceded the incorporation into TAG. These results provide insight into the plasticity and control of acyl lipid metabolism in leaves.

A finite supply of petroleum and a growing demand for energy to support increasingly industrialized nations are global factors that emphasize the vital need to develop renewable and sustainable sources of energy-dense liquid fuels. The demand is further exacerbated by growing populations and concerns linked to fossil fuel use and associated waste streams. Seed-derived plant oils, mainly consisting of triacylglycerol (TAG), provides a sustainable alternative. TAG-based plant oils are one of the most energy-dense compounds found in nature. Plant oils are predominantly used in the food industry (∼80%), with the remainder supplying oleochemical production (Carlsson et al., 2011). Due to their high energy density, they are increasingly viewed as an attractive feed stock for production of biofuels (Lu et al., 2011). Breeding programs and crop research in the last half century have substantially raised yields of oilseed production, taking advantage of improved land, nutrient management, and more efficient farming practices. Nevertheless, further gains in yield will require innovative, if not disruptive, scientific approaches. The amount of arable land is finite and decreasing with urban sprawl. As the world population continues to grow, agriculture production must do more with less to meet food and energy demands. Nonseed-derived plant oils, which can accumulate more lipids per acre of land, are an attractive strategy, including the production of oils in vegetative tissues of high biomass crops (Vanhercke et al., 2019).

Attempts to engineer oil in nonseed tissues have demonstrated increased TAG levels by targeting different aspects of lipid biosynthesis, storage, and protection. These include leaf, stem, tuber, root, or various vegetative tissues, in multiple plant species, including Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), potato (Solanum tuberosum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum; reviewed in Rahman et al., 2016; Xu and Shanklin, 2016; Vanhercke et al., 2019). Our previous work generated a high-oil (HO) tobacco line that accumulated >15% dry weight TAG in leaf tissue by overexpressing the Arabidopsis transcription factor WRINKLED1 (AtWRI1), which upregulates glycolysis and fatty acid synthesis (Focks and Benning, 1998; Cernac and Benning, 2004; Ma et al., 2013); the Arabidopsis TAG biosynthetic enzyme ACYL-CoA:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE 1 (AtDGAT1; Katavic et al., 1995; Zou et al., 1999); and the Sesamum indicum OLEOSIN gene in a combined push-and-pull strategy (Vanhercke et al., 2014). The genetic changes in the HO line produced a large accumulation of fatty acids in leaf TAG. However, the relationship between TAG synthesis and the underlying leaf lipid metabolic network (Fig. 1), including effects on the accumulation of essential leaf photosynthetic membranes, is unknown. The path (or flux) of fatty acids from synthesis in the chloroplast to assembly into TAG in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is critical to effectively control the amount and fatty acid composition of TAG without detrimentally affecting membrane production. In particular for plant oil-based biofuels, TAG containing high levels of monounsaturated fatty acids (e.g. oleate, 18:1 [expressed as number of carbons:number of double bonds]) are desirable for the optimal mix of energy density, cold flow properties, and oxidative stability of the fuels (Durrett et al., 2008). The HO leaves accumulate TAG containing ∼30% oleate and ∼33% polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs; Vanhercke et al., 2014), indicating that substantial improvement of TAG composition may be possible through further engineering. Changes to the PUFA level in plant TAG are dependent on acyl flux through membrane lipid-bound fatty acid desaturases (Bates, 2016), yet the impact of enhanced leaf oil production on acyl flux through this biosynthetic network is less clear (Fig. 1).

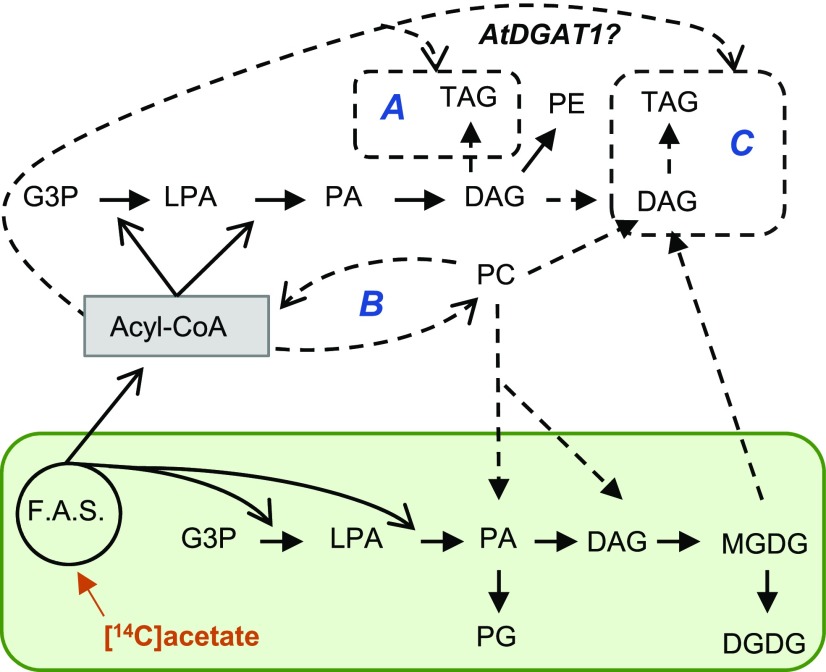

Figure 1.

Model of leaf lipid pathways and hypotheses for acyl flux into TAG. Plastid-localized fatty acid synthesis (F.A.S.) and the chloroplast-localized prokaryotic pathway are in the green box. All other reactions represent extraplastidial metabolism. Solid arrowheads represent flux of the glycerol backbone and open arrowheads represent acyl transfer reactions. Dashed lines and boxes represent uncertainty in acyl flux in HO tobacco lines, and uppercase letters A–C represent three hypotheses for altered acyl flux in HO tobacco lines: the use of de novo DAG by AtDGAT1 for a Kennedy pathway TAG synthesis (A); uncertain quantitative flux through acyl editing that affects incorporation of PC-modified fatty acids in TAG (B); and the use of a membrane lipid-derived DAG by AtDGAT1 for TAG synthesis (C).

Plant leaves have two parallel metabolic pathways of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) acylation to produce membrane glycerolipids, and these have been characterized biochemically and genetically over the past 50 years, and reviewed extensively (e.g. Roughan and Slack, 1982; Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995; Li-Beisson et al., 2013; Hurlock et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2015; LaBrant et al., 2018; Hölzl and Dörmann, 2019). In brief, plants synthesize fatty acids while esterified to acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) in the plastid. The plastid-localized “prokaryotic” pathway of glycerolipid synthesis utilizes ACPs to esterify 18:1 and 16:0 fatty acids to the sn-1 and sn-2 positions, respectively, of G3P, producing first lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), then phosphatidic acid (PA). Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) is produced from prokaryotic PA in the plastid, where only 16:3 plants (including tobacco) also dephosphorylate PA to diacylglycerol (DAG), producing a prokaryotic glycerolipid backbone containing a sn-2 16-carbon fatty acid for synthesis of some of the plastid-localized galactolipids, monogalactosyldiacyglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG; Mongrand et al., 1998). Plastid-localized desaturases produce the 16:3 by desaturation of the 16:0 incorporated into the sn-2 position of MGDG and DGDG (Li-Beisson et al., 2013). The glycerolipid backbone for the remaining galactolipids (or all galactolipids in 18:3 plants) is produced by the “eukaryotic” pathway utilizing ER-localized lipid assembly enzymes. In the eukaryotic pathway, free fatty acids are exported from the plastid and activated to acyl-CoAs prior to utilization by extraplastidic acyltransferases. The production of PA parallels that of the prokaryotic pathway, except that 18-carbon fatty acids are found at both sn-1 and sn-2. Any 16:0 present is localized to the sn-1 position (Frentzen et al., 1983) and is not further desaturated. Subsequent dephosphorylation of PA produces the eukaryotic DAG backbone for synthesis of the major ER membrane lipids phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE; Li-Beisson et al., 2013). The production of eukaryotic galactolipids involves the plastid-localized assembly of MGDG from a eukaryotic DAG moiety derived from PC, although the exact lipid that is transported from the ER to the plastid is unclear—it could be PC, or the PC-derived intermediates PA or DAG (Hurlock et al., 2014; Maréchal and Bastien, 2014; LaBrant et al., 2018; Karki et al., 2019).

Direct production of leaf TAG containing oleate in the HO tobacco line could occur through utilization of newly synthesized oleoyl-CoA by the Kennedy pathway (Fig. 1, option A); however, the presence of PUFA in HO TAG indicates that other mechanisms of acyl flux must be involved. Reactions that exchange acyl groups on and off PC are integral to the eukaryotic pathway. PC is the site of ER-localized fatty acid desaturation of oleate (18:1Δ9) to make the PUFAs linoleate (18:2Δ9,12) and α-linolenate (18:3Δ9,12,15; Li-Beisson et al., 2013). PUFAs can enter the acyl-CoA pool to be used by the eukaryotic pathway acyltransferases through a PC deacylation and lyso-PC acylation cycle coined “acyl editing” (Fig. 1, option B; Bates et al., 2007). Through acyl editing oleate is incorporated into PC for desaturation, and the corresponding PUFA can reenter the acyl-CoA pool to be used for the synthesis of glycerolipids by Kennedy pathway reactions (Bates, 2016). Quantitative analysis of acyl flux through the eukaryotic pathway with in vivo metabolic labeling has indicated that most nascent fatty acids first are incorporated into PC through acyl editing prior to acylation of G3P, and that fatty acid flux around the acyl editing cycle is the largest lipid metabolic flux in many plant tissues, including those of developing pea (Pisum sativum) leaves (Bates et al., 2007); soybean (Glycine max) and camelina (Camelina sativa) embryos (Bates et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2017); and Arabidopsis seeds, leaves, and cell cultures (Bates et al., 2012; Tjellström et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Karki et al., 2019). Mechanisms of acyl transfer from membrane lipids into TAG also include membrane lipid turnover resulting in DAG containing PUFAs that are used for TAG biosynthesis (Fig. 1, option C; Bates, 2016). In various oilseed tissues, PC-derived DAG is the major source for TAG synthesis (Bates et al., 2009; Bates and Browse, 2011; Yang et al., 2017). In leaves, DAG derived from chloroplast galactolipids can also be used to produce TAG by homeostatic mechanisms (Xu and Shanklin, 2016), and during stress (Sakaki et al., 1990; Moellering et al., 2010; Narayanan et al., 2016; Arisz et al., 2018). Thus, the composition of TAG produced in leaves is a consequence of the relative rates of acyl flux through various membrane lipid pools and the relative rate of fatty acid desaturation within these lipid pools.

The expression of the genes encoding AtWRI1, AtDGAT1, and sesame OLEOSIN have led to an increased level of fatty acid synthesis and accumulation of TAG in leaves of the HO tobacco line (Vanhercke et al., 2014). Transcriptomic analysis of the HO line indicated up-regulation of glycolysis and fatty acid synthesis (Vanhercke et al., 2017), consistent with the function of WRI1 in plant tissues (Focks and Benning, 1998; Ma et al., 2013). However, there was little to no change in expression of the acyltransferases involved in TAG and membrane lipid assembly (Vanhercke et al., 2017). Previous studies have indicated that transcript abundance may not correlate with protein levels (Hajduch et al., 2010; Vogel and Marcotte, 2012), and transcript abundance alone is a poor indicator of metabolic flux (Fernie and Stitt, 2012; Schwender et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2015). Thus, the path of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network into TAG, including whether turnover of the abundant chloroplast lipids in leaves may be feeding TAG biosynthesis, is unclear (Fig. 1, options A–C). Future leaf oil engineering efforts may need to specifically target these facets of the lipid metabolic network to optimize leaf TAG accumulation and composition. Therefore, to better understand the pathways of acyl flux in wild-type tobacco leaves, and how these pathways are altered when accumulating high levels of leaf TAG in the transgenic HO line, we performed a series of in vitro enzymatic assays and in vivo continuous-pulse and pulse-chase metabolic labeling studies that provide new insights into tobacco leaf lipid metabolism and its engineering.

RESULTS

Engineering Leaf TAG Accumulation Also Effects the Accumulation of Leaf Membrane Lipids

The HO line has a large increase in leaf TAG accumulation (Vanhercke et al., 2014), which was confirmed in the current effort. Our results indicate that the boost in TAG was accompanied by changes to leaf membrane lipid abundance (Fig. 2). PC and DAG increased, whereas other membrane lipids, including the galactolipids that are the bulk of the chloroplast photosynthetic membranes, decreased in abundance compared to the wild-type (Fig. 2A). The difference in lipid abundance was also reflected through changes in fatty acid composition (Fig. 3). Total leaf fatty acid composition (Fig. 3A) of the HO line reflected alterations in the fatty acid composition of TAG (Fig. 3B), which accumulated as the major lipid product (Fig. 2A). PC had a notable decrease in the unsaturation index as 18:3 decreased and 18:1 significantly increased (Fig. 3C). MGDG 16:3 content decreased by half and 18:2 significantly increased (Fig. 3D). The change in MGDG fatty acid composition was predominantly due to a reduction in 16-carbon fatty acids at the sn-2 position, indicating an ∼40% reduction in the proportion of prokaryotic pathway-produced MGDG (Supplemental Fig. S1, A–C).

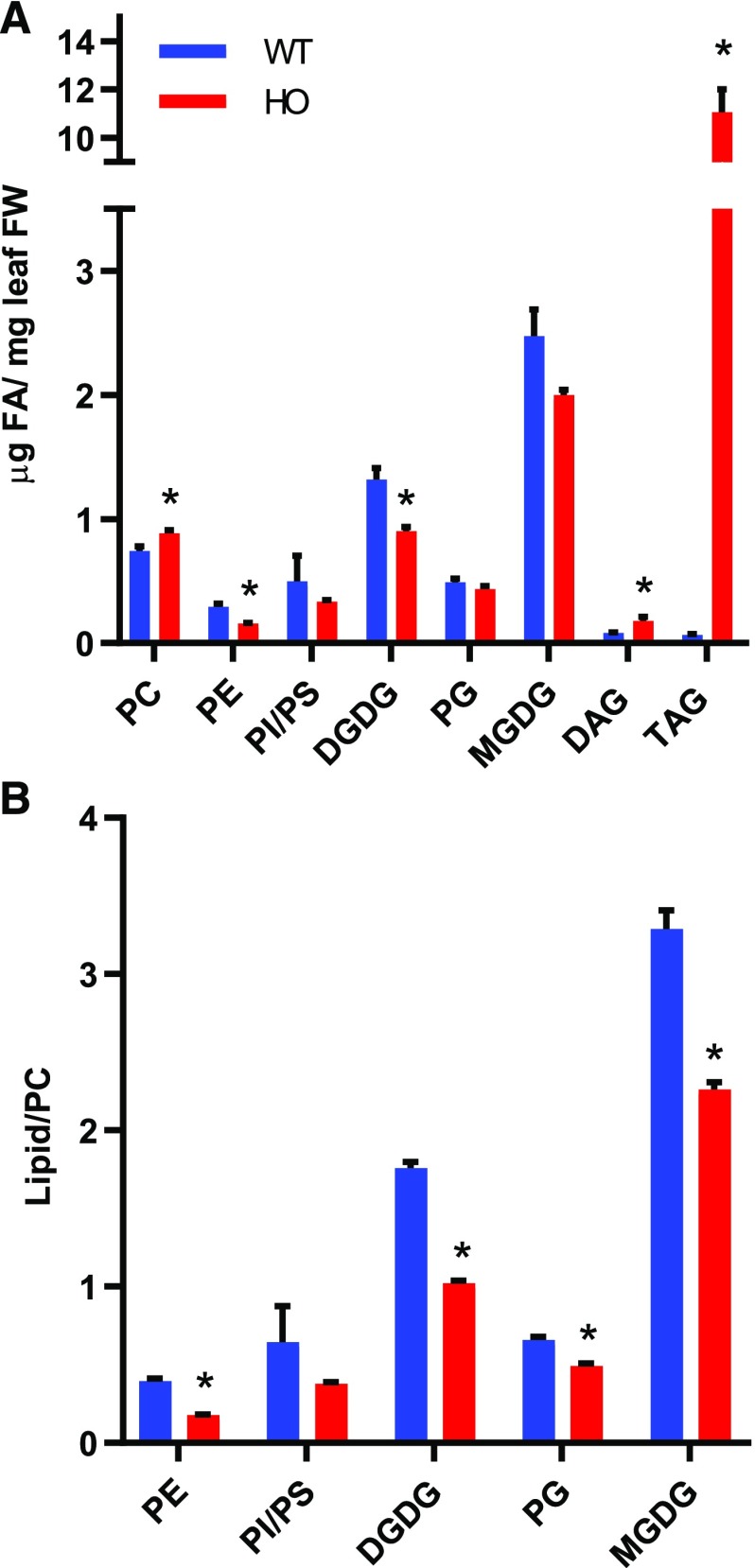

Figure 2.

Accumulation of lipids in wild-type (WT) and HO leaves. The abundance of polar membrane lipids and neutral lipids was measured in leaves of 86-d-old plants. A, Mass abundance of each lipid. B, Ratio of mass abundance of lipid to PC. Data for the wild type are in blue, and those for HO are in red. Data are the average ± se for three to four replicates. Significant differences from the wild type in the HO line (Student’s t test, P < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine; FW, fresh weight.

Figure 3.

Fatty acid composition of wild-type (WT) and HO leaf lipids. The weight percent fatty acid composition of lipid classes isolated from leaves of 86-d-old plants is shown. A, Total leaf extract. B, TAG. C, PC. D, MGDG. Data for the wild type are in blue, and those for HO are in red. Data are the average ± se for three to four replicates. Significant differences from the wild type in the HO line (Student’s t test, P < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. TAG fatty acids are configured as number of carbons:number of double bonds, and a number preceded by “d” indicates a delta double bond position.

Considering that acyl and glycerol flux through PC are key to producing other membrane lipids, we calculated the ratio of membrane lipids to PC (Fig. 2B). The lipid:PC ratios dropped in the HO line and indicated a change in the redistribution of fatty acid from PC to other lipids, though it is less clear whether this is a consequence of reduced biosynthesis or enhanced turnover or both. To better understand the changes in the lipid metabolic network that accommodate TAG accumulation, the flux of acyl groups through the lipid metabolic network was analyzed by both in vitro assays and in vivo tracing of leaf lipid metabolism in the wild type and the HO line.

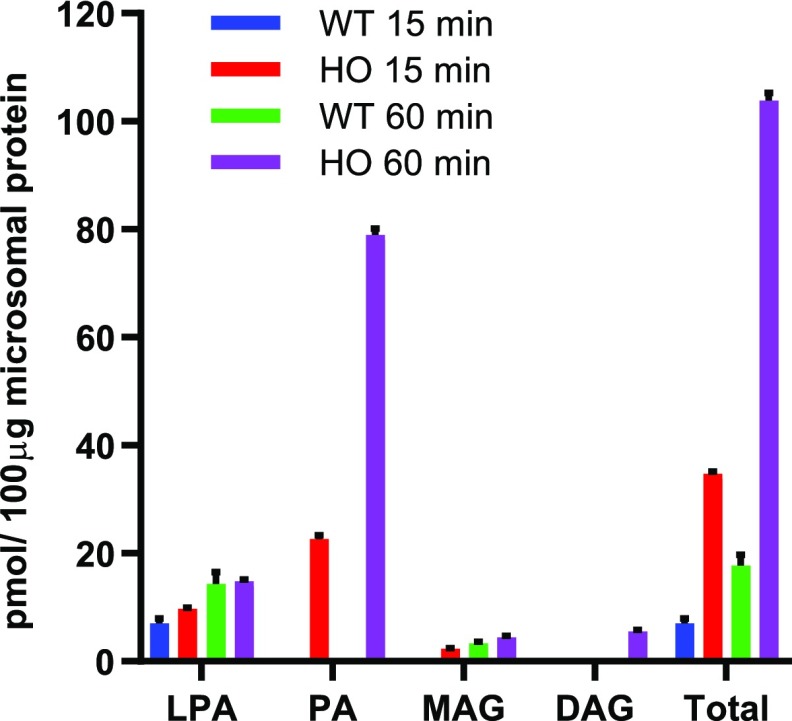

A Direct Linear Kennedy Pathway of TAG Biosynthesis Is Not Active in Wild-type or HO Leaf Microsomes

Microsomal studies have been invaluable in characterizing enzymatic functions that produce TAG through the linear Kennedy pathway in plants (Barron and Stumpf, 1962; Stymne and Stobart, 1984; Bafor et al., 1991). To determine whether a direct Kennedy pathway of TAG biosynthesis (Fig. 1, option A) is present, we assayed wild-type and HO tobacco leaf microsomes for TAG production with [14C]G3P and 18:1-CoA (Fig. 4). No significant TAG accumulation was detected within a 60-min assay, though the total label in lipids produced by HO microsomes was ∼5-fold higher than that in the wild type, suggesting an overall up-regulation in de novo glycerolipid assembly. In the HO line, PA was the major labeled product, suggesting that PA conversion to DAG may be limiting in the isolated microsomes. The in vitro results indicate that efficient channeling of substrates into TAG through a Kennedy pathway (Fig. 1, option A) may not occur in the HO line; however, since some proteins can be lost during microsomal preparation, additional in vivo pulse and pulse-chase metabolic labeling experiments were performed to further study the acyl flux through lipids.

Figure 4.

In vitro assay of the Kennedy pathway in leaf microsomes. Assay conditions included 100 μg of leaf microsomal protein and 12.5 nmol [14C]G3P + 25 nmol of 18:1-CoA, incubated for 15 or 60 min. For each assay duration, data are the average ± se of three replicates. MAG, monoacylglycerol; WT, wild type.

TAG Accumulation Alters the Relative Flux of Nascent Fatty Acids into the Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Pathways of Glycerolipid Assembly

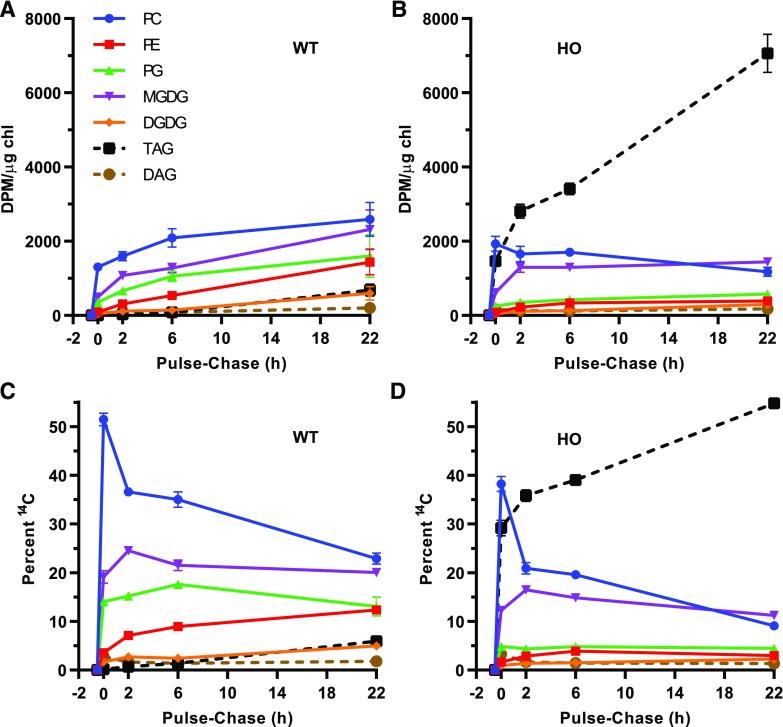

To understand how the push-and-pull engineering approach to produce leaf TAG (Vanhercke et al., 2014) affects the initial flux of newly synthesized fatty acids into the endogenous leaf lipid metabolic network (Fig. 1), we performed a continuous [14C]acetate metabolic labeling of 3–120 min on leaf disks from 66-d-old wild-type and HO plants. [14C]acetate is incorporated into the acetyl-CoA pool utilized for fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 1), and short time point labeling is instructive for characterizing the initial steps of nascent acyl flux into the lipid metabolic network (Allen et al., 2015). Total incorporation of [14C]acetate into leaf lipids was linear for both the wild type and the HO line over the 120-min time course, and there was no statistical difference in total label between genotypes at any time point (Supplemental Fig. S2). However, linear regression indicated slopes of 50.5 ± 1.9 disintegrations/min (DPM) µg chlorophyll (chl)−1 min−1 in the wild type and 43.1 ± 1.3 DPM µg chl−1 min−1 in the HO line. The slopes were significantly different, with P = 0.0035. The reason for the reduced slope of [14C]acetate incorporation into lipids of the HO line is not immediately clear, but it could be due to dilution of the exogenous [14C]acetate by the much larger flux of endogenous carbon into acetyl-CoA and fatty acid production in the HO leaf cells compared to that in the wild type. Therefore, we normalized the total accumulation of HO lipids to the wild-type average total lipid accumulation at each time point (Fig. 5) so that the relative rates of synthesis of individual lipid classes between the genotypes could be compared. The normalization slightly increased the total DPM µg chl−1 in each lipid class, but the pattern of lipid synthesis essential for determining precursor-product relationships was unchanged regardless of whether data were normalized (Fig. 5) or not (Supplemental Fig. S3).

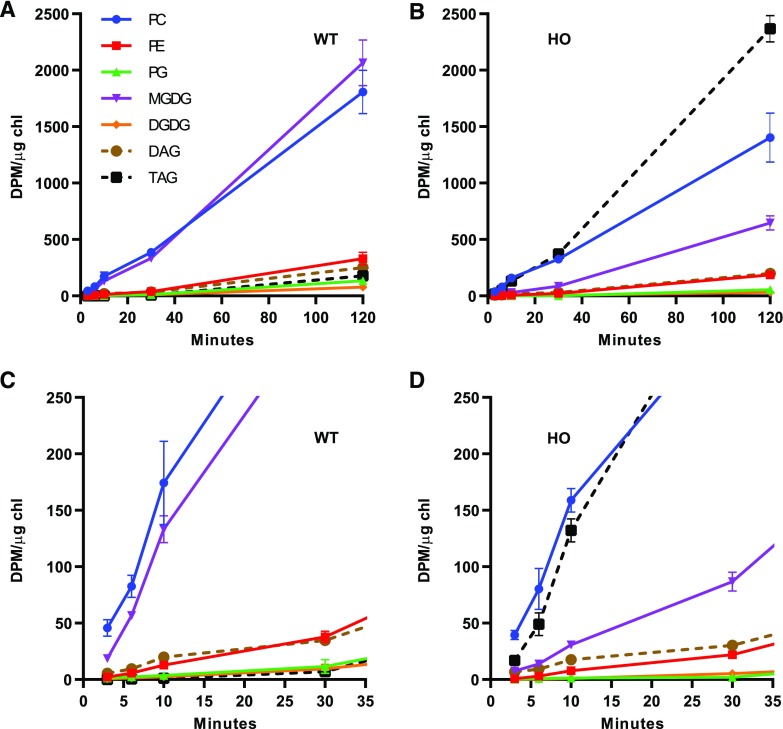

Figure 5.

Initial incorporation of nascent [14C]acetate labeled fatty acids into lipids. A and B, Major labeled lipids from continuous [14C]acetate labeling for 3–120 min in leaf disks of 66-d-old plants of the wild type (WT) and the HO line. C and D, An expanded view of the first 35 min of the labeling in A and B. All data points are the average ± se of three biological replicates.

In wild-type leaves, most newly synthesized fatty acids accumulate in PC and MGDG across the time course, with only minor amounts in TAG (Fig. 5A). At early time points, PC is the major labeled lipid (Fig. 5C), and both PC and MGDG accumulate labeled fatty acids at similar initial rates (Table 1), but by 120 min MGDG accumulates more label (Fig. 5, A and C). These results are consistent with (1) PC as a first product of nascent fatty acid incorporation into ER lipids (Bates et al., 2007; Tjellström et al., 2012); (2) de novo synthesis of MGDG through the prokaryotic pathway; and (3) the precursor-product relationship of PC and MGDG over time as acyl groups move through the eukaryotic pathway of galactolipid synthesis (Li-Beisson et al., 2013). All other membrane lipids initially accumulated little radiolabel, but slowly increased over time. This is consistent with the redistribution of nascent fatty acids from PC to other lipids through acyl editing (Bates et al., 2007; Bates, 2016) and the conversion of MGDG to DGDG within the plastid (Kelly and Dörmann, 2004; Hurlock et al., 2014; LaBrant et al., 2018).

Table 1. Initial rates of nascent fatty acid incorporation into individual lipid classes.

Rates (DPM µg chl−1 min−1) are the slope best fit ± se from the linear regression of the first 10 minutes of [14C]acetate labeling from Figure 5. P values indicate whether the slopes are significantly different (P < 0.05) between the wild type and the HO line. Significantly different rates for HO are marked with an asterisk. The fold change (F.C.) for lipids with significantly different rates are indicated.

| PC | PE | PG | MGDG | DGDG | DAG | TAG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 18.59 ± 2.97 | 1.53 ± 0.17 | 0.31 ± 0.004 | 16.49 ± 1.79 | 0.28 ± 0.0001 | 2.08 ± 0.35 | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| HO | 17.2 ± 1.7 | 1.04 ± 0.13 | *0.16 ± 0.02 | *3.36 ± 0.59 | *0.11 ± 0.01 | 1.57 ± 0.37 | *16.68 ± 2.83 |

| P value | 0.7234 | 0.1444 | 0.0263 | 0.0199 | 0.0075 | 0.4212 | 0.0281 |

| F.C. | – | – | −1.9 | −4.9 | −2.5 | – | 119.1 |

The incorporation of nascent fatty acids into lipids of HO leaves was dramatically different (Fig. 5, B and D). Similar to the wild type, in the HO line, PC was the most labeled lipid at the earliest time points (Fig. 5D) and had a similar rate of label accumulation (Table 1). However, the next most labeled lipid was TAG (rather than MGDG as in the wild type; Fig. 5C) and the initial rate of nascent fatty acid incorporation into TAG was 119-fold higher than in the wild type (Table 1). At the 3-min time point there was over twice the amount of nascent fatty acids in PC (39.5 ± 3.9 DPM/µg chl) as in TAG (17.0 ± 4.4 DPM/µg chl). However, the accumulation of labeled fatty acids in TAG continued to accelerate, surpassing that in PC by 15 min, and by 120 min TAG accumulated 1.7-fold more labeled fatty acids than PC, representing ∼48% of total labeled lipids (Fig. 5, B and D). This result is consistent with the very large mass accumulation of TAG in HO leaves (Fig. 2). Despite the larger mass accumulation of TAG over time, the more rapid labeling of PC at initial time points suggests a PC-TAG precursor-product relationship for fatty acid flux.

PE, which, similar to PC and TAG, is produced in the ER through the eukaryotic pathway, did not have a significant difference in the rate of synthesis with nascent fatty acids in the wild type and the HO line (Table 1). However, there was a significant decrease in the rates of nascent fatty acid incorporation into chloroplast lipids MGDG (−4.9-fold), DGDG (−2.5-fold), and PG (−1.9-fold; Fig. 5; Table 1) in the HO line as compared to the wild type. For each of these lipids, the initial rate of labeling represents synthesis through the prokaryotic pathway, whereas that through the eukaryotic pathway occurs over much longer time scales as labeled fatty acids move through PC and ER-derived lipids and eventually return to the chloroplast (Browse et al., 1986). Therefore, the results suggest a shift in fatty acid allocation to the eukaryotic pathway over the prokaryotic pathway for the production of TAG in the transgenic line.

In Figure 6, we estimated the relative flux of nascent fatty acids into the eukaryotic and prokaryotic glycerolipid assembly pathways by comparing the accumulation of label in ER-localized (PC, PE, and TAG) and plastid-localized (MGDG, DGDG, and PG) lipids. The metabolic labeling of wild-type leaves showed that nascent fatty acids accumulated in ER lipids at a slightly greater rate than in plastid lipids (Fig. 6A). Linear regression of the initial phase of glycerolipid assembly (first 10 min) indicated that flux of newly synthesized fatty acids into glycerolipids was 20.3 ± 4.6 and 17.1 ± 1.5 DPM µg chl−1 min−1 for ER and plastid lipids, respectively. The initial ER:plastid ratio at 3 min of labeling was ∼2.4 but dropped to 1.3 by 10 min. This change is likely reflected by the lipids quantified at these time points. In the eukaryotic pathway, nascent fatty acids exported from the plastid are initially directly incorporated into PC, but in the prokaryotic pathway nascent fatty acids are first incorporated into LPA, PA, and DAG prior to MGDG synthesis (Allen et al., 2015). Considering that lipid classes LPA, PA, and DAG occur in both pathways (Fig. 1), they were not included in the analysis. Therefore, the lag in acyl flux through intermediates of the prokaryotic pathway at short time points may explain the ratio favoring the eukaryotic pathway at short time points. The changing ratio of labeled fatty acids in ER lipids to those in plastid lipids stabilized by 10 min, then slowly decreased over the time course. However, in the HO line, the relative initial rates of newly synthesized fatty acid accumulation in ER and plastid lipids were 34.9 ± 4.6 and 3.6 ± 0.6 DPM µg chl−1 min−1, respectively. Thus, the eukaryotic pathway accounted for a 9-fold higher flux of fatty acids into glycerolipids than the prokaryotic pathway of the HO line. Similar to the wild type, in the HO line, the ER:plastid ratio for labeled fatty acid accumulation stabilized by 10 min and then decreased over the time course (Fig. 6B). The decrease in the ER:plastid ratio over time in both genotypes likely represents the PC-galactolipid precursor-product relationship of the eukaryotic pathway.

Figure 6.

Relative incorporation of nascent fatty acids into the eukaryotic and prokaryotic pathways of wild-type (WT; A) and HO (B) leaves. ER-localized lipids (PC, PE, and TAG) and plastid-localized lipids (PG, MDGD, and DGDG) from Figure 5 were added together, and the ratio of the two compartments was monitored. DAG was not included, because it can be localized to multiple compartments. All data points are the average ± se of three biological replicates.

In Figures 5 and 6, the accumulation of newly synthesized fatty acids in MGDG can be due to both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways. To determine whether the reduction in accumulation of labeled MGDG is due to reduced acyl flux through the prokaryotic or eukaryotic pathway, or both pathways, we collected MGDG from the 30- and 120-min time points and analyzed the radioactivity in individual molecular species (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). The prokaryotic pathway initially produces the 18:1/16:0 molecular species of MGDG, which is further desaturated to predominantly 18:3/16:3 (Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). Eukaryotic MGDG is indicated to be synthesized from a polyunsaturated-containing DAG ultimately derived from PC, and is further desaturated to predominantly 18:3/18:3 in the plastid (Slack et al., 1977; Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). Therefore, 18/16-carbon-containing molecular species are representative of the prokaryotic pathway, and 18/18-carbon molecular species are representative of the eukaryotic pathway. The accumulation of MGDG through each pathway is summarized in Table 2. The analysis of MGDG molecular species gave four insights into the acyl flux through the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways: (1) the HO line had a reduced proportion of prokaryotic MGDG molecular species (and thus an increased eukaryotic proportion) compared to the wild type; (2) however, with the very large decrease in total 14C-MGDG accumulation (Fig. 5), the total acyl flux into MGDG through the eukaryotic pathway was reduced by >30% and acyl flux through the prokaryotic pathway was reduced by >70% (Table 2); (3) both lines had an increase in eukaryotic molecular species from 30 to 120 min of labeling (Table 2), consistent with the role of the eukaryotic pathway in PC turnover to produce plastid galactolipids, and with the decrease in the ER:plastid accumulation ratio of Figure 6; (4) the profile of prokaryotic and eukaryotic MGDG molecular species in the HO line suggested a reduced rate of plastid desaturation compared to the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S5). Therefore, an increase in the total flux of newly synthesized acyl groups into ER lipids (mostly TAG; Figs. 5 and 6), and a reduction in acyl flux into plastid lipids through both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways (Table 2) contributed to the dramatic redistribution of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network in the HO tobacco line.

Table 2. Acyl flux into eukaryotic and prokaryotic molecular species of MGDG.

The average total MGDG (DPM/µg chl) at 30 and 120 min was taken from Figure 5. Proportions of eukaryotic and prokaryotic molecular species are from Supplemental Figure S5. The DPM/µg chl values for eukaryotic and prokaryotic MGDG molecular species are calculated from the total label and the relative proportion of each species. The “HO % of wild type DPM” is the amount of HO eukaryotic or prokaryotic MGDG as compared to the wild type at each time point.

| Samples: | Wild Type 30 min | HO 30 min | HO % of Wild Type DPM | Wild Type 120 min | HO 120 min | HO % of Wild Type DPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average total DPM/µg chl | 335.2 | 86.7 | – | 2066.4 | 646.6 | – |

| Eukaryotic proportion | 9.6% | 20.9% | – | 11.4% | 25% | – |

| DPM/µg chl | 32.2 | 18.1 | 56.3% | 234.5 | 161.7 | 69% |

| Prokaryotic proportion | 90.4% | 79.1% | – | 88.6% | 75% | – |

| DPM/µg chl | 303.0 | 68.2 | 22.6% | 1831.9 | 484.6 | 26.5% |

Regiochemical Analysis Indicates Limited Changes in Pathway Structure for Initial Steps of ER Glycerolipid Assembly

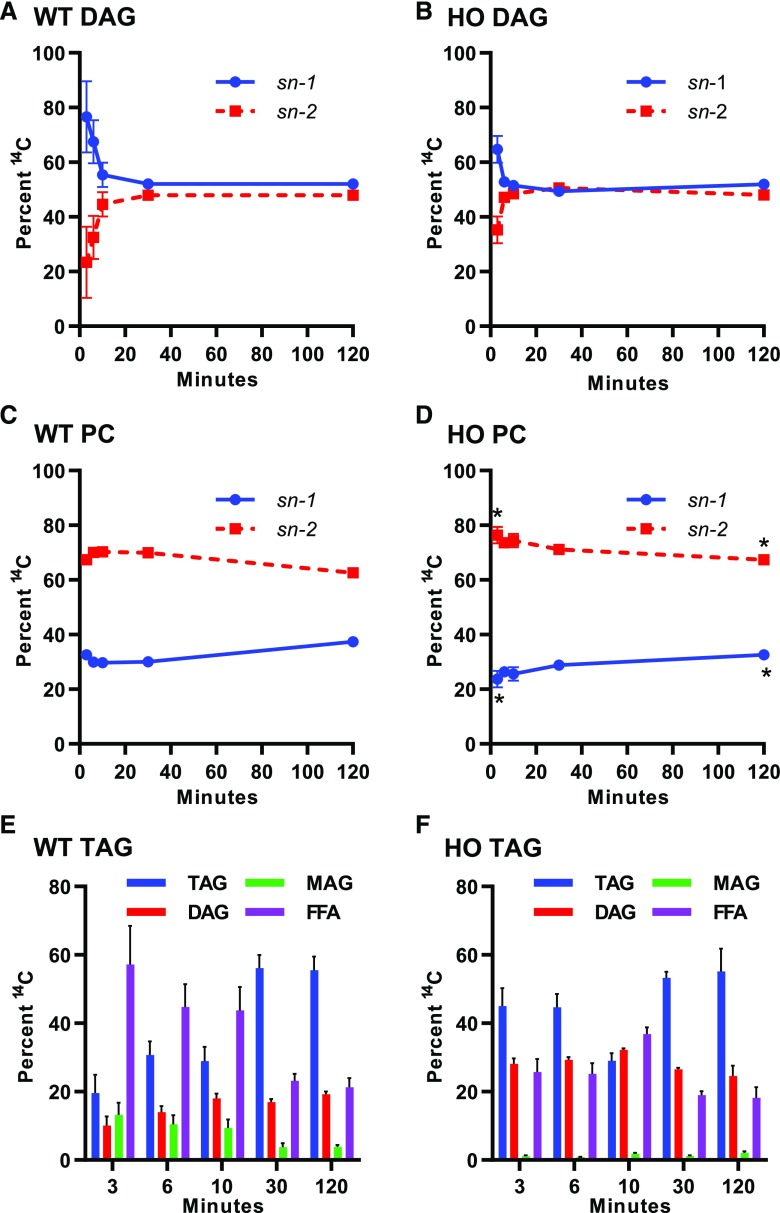

To better understand which branches of the lipid metabolic network (Fig. 1) are involved in the altered flux of nascent fatty acids into membrane lipids and TAG of the HO line as compared to the wild type, we performed regiochemical analysis (Fig. 7) of labeled DAG, PC, and TAG across the [14C]acetate labeling time course from Figure 5. In both the wild type and the HO line, newly synthesized fatty acids were initially incorporated more on the sn-1 position than on the sn-2 position of the total labeled DAG pool, but this was quickly equilibrated to approximately equal distribution by 10 min (Fig. 7, A and B), and there was no statistical difference in stereochemical labeling in DAG between the lines. The higher initial labeling of DAG sn-1 position over sn-2 has previously been reported in the predominantly eukaryotic de novo DAG pools of developing soybean embryos and Arabidopsis seeds (Bates et al., 2009, 2012). Rapid equilibrium of labeling across stereochemical positions in tobacco plants may also represent a substantial contribution of prokaryotic DAG, which is produced from only nascent fatty acids (Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995), and thus the labeled fatty acids will be evenly distributed across both positions, as demonstrated for prokaryotic lipids in rapeseed (Brassica napus) leaves (Williams et al., 2000). In contrast to DAG, newly synthesized fatty acids accumulated predominantly in the sn-2 position of PC across the time course in both plant lines (∼63% to 70% wild type and 67% to 76% HO). The presence of slightly more nascent fatty acids at the sn-2 position of PC in the HO line was only significant at the 3- and 120-min time points (Fig. 7, C and D). The PC stereochemical labeling is consistent with previous leaf, seed, and cell culture analyses where a single nascent fatty acid is initially incorporated next to a previously synthesized fatty acid within PC (with preference for sn-2 over sn-1) through acyl editing as nascent fatty acids leave the plastid (Bates et al., 2007, 2009, 2012; Tjellström et al., 2012; Allen, 2016a; Bates, 2016; Karki et al., 2019).

Figure 7.

Regiochemical analysis of initial incorporation of nascent [14C]acetate labeled fatty acids into DAG, PC, and TAG. A and B, TAG lipase digestion of DAG from the wild type (WT) and the HO line. C and D, Phospholipase A2 digestion of PC from the wild type and the HO lines. E and F, TAG lipase digestion of TAG from the wild type and the HO line. All data points are the average ± se of three biological replicates. Asterisks in D indicate statistically significant differences in the HO line relative to the wild type (Student’s t test, P < 0.05). FFA, free fatty acid; MAG, monoacylglycerol.

Partial TAG lipase digestions of labeled TAG from both plants revealed that most labeled acyl groups were released by the lipase in the free fatty acid fraction (sn-1 or sn-3) and little remained in the monoacylglycerol fraction (sn-2; Fig. 7, E and F). Considering the similar labeling of the sn-1 and sn-2 positions of DAG, the low sn-2 labeling of TAG suggests that most TAG labeling within this short time course represents incorporation of a newly synthesized radiolabeled fatty acid on the sn-3 position of an unlabeled DAG molecule, and does not reflect the rapidly produced eukaryotic de novo DAG that might be expected from a direct Kennedy pathway of TAG synthesis (Fig. 1, option A). Together, the DAG, PC, and TAG regiochemical analysis suggests that even though there are big differences between the wild type and the HO line in the quantity of acyl flux into eukaryotic pathway lipids, the initial steps of eukaryotic glycerolipid assembly (or the initial structure of the eukaryotic lipid network) between these genotypes do not vary considerably.

Nascent Acyl Groups Initially Incorporated into PC Are Redistributed Differently between the Wild Type and the HO Line

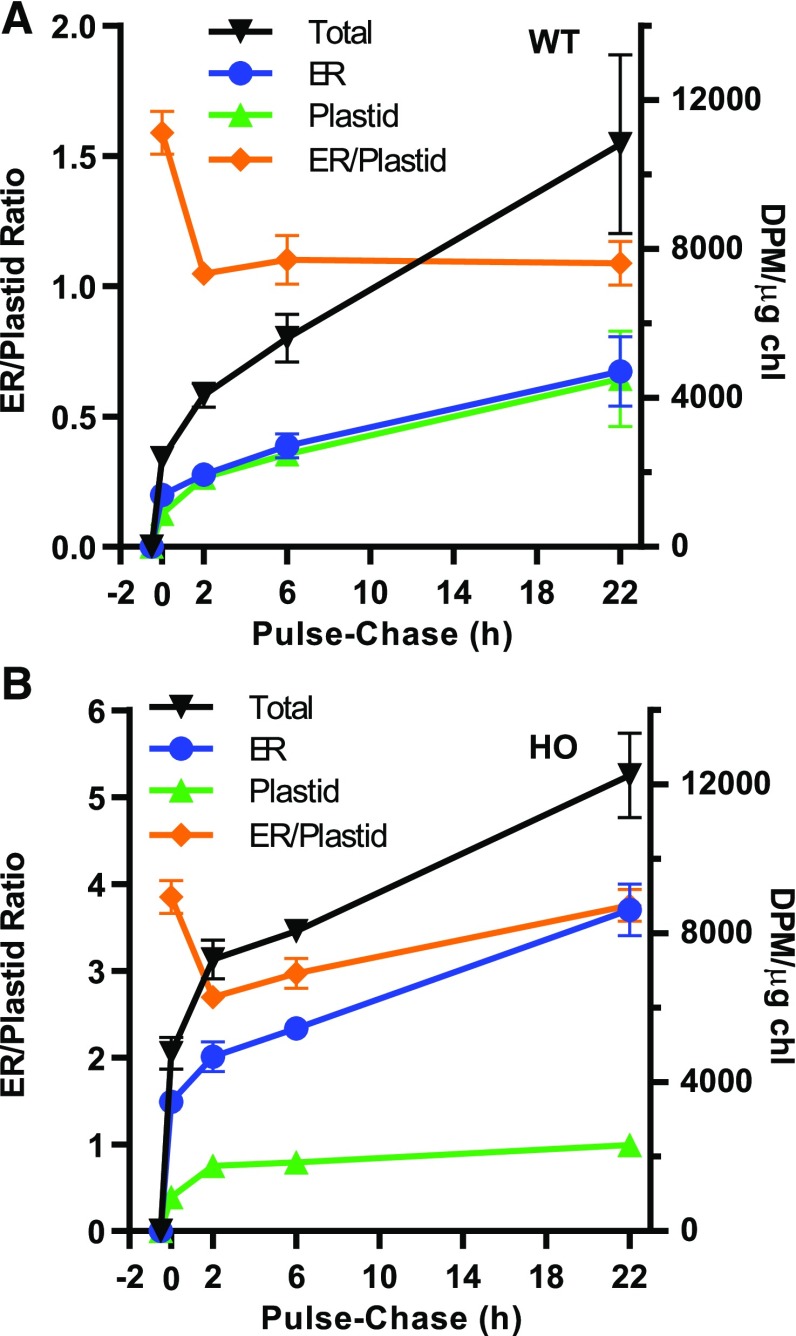

The short time point [14C]acetate labeling in Figure 5 demonstrated that a majority of newly synthesized fatty acids are initially incorporated into PC of both genotypes. The redistribution of fatty acids from PC to other lipids over time was assessed through an additional pulse-chase experiment (Figs. 8 and 9). Leaf disks of 73-d-old plants were pulsed with [14C]acetate for 0.5 h, rinsed, and incubated without the radiolabel for up to 22 h. In both plants, the total 14C-labeled lipids increased throughout the pulse and chase periods (Fig. 8). During the pulse, labeled lipids accumulated at the most rapid rates (4,800 ± 500 and 9,600 ± 900, DPM µg chl−1 h−1 in wild-type and HO lines, respectively). During the first 2 h of the chase period the rate of labeled lipid accumulation was reduced 6- to 7-fold to 840 ± 210 and 1,300 ± 340 DPM µg chl−1 h−1 in wild-type and HO leaves respectively, which likely represents continued uptake of [14C]acetate during the washes. Finally from 2 to 22 h, radiolabel accumulated at even slower but constant rates of 330 ± 90 and 250 ± 50 DPM µg chl−1 h−1, which may represent continued utilization of a pool of [14C]acetate that was taken up into the leaf tissue during the pulse but utilized at a slower rate, as compared to the bulk of the [14C]acetate substrate. Therefore, the experiment should be considered a rapid 14C pulse that is followed by labeling with a significantly lower concentration of [14C]acetate (15- to 38-fold lower based on initial and final rates). This distinction is relevant when comparing the total accumulation of radiolabel in individual lipid classes (Fig. 9, A and B) to the relative radiolabel accumulation between lipid classes in each genotype (Fig. 9, C and D). Similar to the short-time-point pulse experiment (Figs. 5 and 6), the HO line accumulated labeled fatty acids predominantly in ER lipids across the time course, whereas labeling of ER and plastid lipids was similar across the time course in the wild type (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Pulse-chase [14C]acetate accumulation in lipids of the wild type (WT) and the HO line. The pulse starts at −0.5 h, and the chase starts at 0 h. The leaves of 73-d-old plants were used for both plants. A and B, The wild type and HO line demonstrate the total 14C incorporated into the lipid extract; the ER-localized lipids (PC, PE, and TAG) and the plastid-localized lipids (PG, MDGD, and DGDG) were added together, and the ratio of the two compartments was monitored. DAG was not included because it can be localized to multiple compartments. All data points are the average ± se of three biological replicates.

Figure 9.

Pulse-chase [14C]acetate labeling of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network. The pulse starts at −0.5 h, and the chase starts at 0 h. Leaves of 73-d-old plants were used for both plants. A and B, Accumulation of individual radiolabeled lipids as DPM/µg chl from the total labeled samples in Figure 8. C and D, The labeled lipids in A and B are represented as a percentage of the sum. All data points are the average ± se of three biological replicates.

In the wild type, all individual lipid classes accumulated 14C acyl groups during the pulse-chase, but at different rates across the time course (Fig. 9A). At the end of the pulse, PC contained the most 14C, with >2.6-fold more 14C than any other lipid, but the rate of labeled fatty acid accumulation in PC continued to slow down across the chase time course. During the chase, the accumulation of 14C fatty acids increased in MGDG relative to PC such that by the end of the time course they contained similar amounts of total labeled fatty acids. The results are consistent with the PC-MGDG precursor-product relationship of the eukaryotic pathway in leaves, and the redistribution of nascent acyl groups from PC to other ER-localized lipids through acyl editing (Fig. 1). In HO leaves, the [14C]acetate pulse-chase results are distinct. Initially PC contained the most label after the pulse but was surpassed by TAG before the 2 h time point (Fig. 9, B and D). By the end of the 22-h chase period, TAG accumulated ≥4.9-fold more 14C fatty acids than any other lipid. Although the total lipid labeling increases over the chase period (Fig. 8B), the amount of labeled fatty acids in PC of the HO line decreases over the whole chase period (Fig. 9B). The difference in accumulation of 14C fatty acids in PC between the wild type and the HO line suggests that PC turnover and redistribution of acyl groups occurs at a higher rate in the HO line. All other membrane lipids in HO leaves increased slightly during the chase (Fig. 9B), but much less than in wild-type leaves. In the wild type, PC and MGDG had a clear precursor-product relationship of acyl flux that is not directly evident in the HO line (Fig. 9B). To determine whether the small increases in HO MGDG 14C acyl accumulation are due to (1) the continued synthesis of 14C fatty acids and their incorporation into the metabolic network during the chase (Fig. 8B) or (2) a reduced redistribution of acyl label from PC, we compared the labeled MGDG molecular species distribution at the 0 and 22-h time points (Supplemental Fig. S6; summarized in Table 3). After the 30 min pulse, the proportion of eukaryotic and prokaryotic MGDG molecular species in both the wild type and the HO line was similar to that of the 30-min continuous labeling time point (Table 2). During the 22-h chase period in the wild type, the eukaryotic MGDG molecular species increased 3-fold as a proportion (Table 3), consistent with the PC-MGDG precursor-product relationship of the eukaryotic pathway. However, during the chase in the HO line, the proportion of eukaryotic MGDG molecular species only increased 1.5-fold (Table 3). Therefore, the reduced accumulation of MGDG in the HO line during the chase (Fig. 9B) is also consistent with a reduced redistribution of acyl groups from PC to MGDG through the eukaryotic pathway MGDG.

Table 3. Change in MGDG eukaryotic and prokaryotic molecular species over the [14C]acetate pulse-chase.

The proportion of eukaryotic and prokaryotic molecular species are from Supplemental Figure S6. F.C., fold-change.

| Samples | Wild Type 0 h | Wild Type 22 h | 0–22 h F.C. | HO 0 h | HO 22 h | 0–22 h F.C. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic proportion | 12.8% | 38.6% | 3.0 | 20.4% | 31.5% | 1.5 |

| Prokaryotic proportion | 87.2% | 61.4% | 0.7 | 79.5% | 68.5% | 0.86 |

Pulse-chase experiments are commonly represented as the percent labeling in the different products over time (Fig. 9, C and D), yet the interpretation is dependent on the relative accumulation of the total lipids (Fig. 8, A and B) and each individual lipid (Fig. 9, A and B) over the chase period. In both genotypes, PC had the largest decrease in proportional labeling, consistent with the conclusions from above that acyl groups are redistributed from PC to other lipids over the time course. However, considering that nascent 14C acyl groups continue to enter the system during the chase (Fig. 8) and are predominantly incorporated into PC first (Fig. 5, Fig. 9), the actual turnover of PC is greater than the apparent turnover of half of the labeled PC in wild-type leaves and >76% of the labeled PC in HO leaves. In addition, the proportional labeling of MGDG in both genotypes also decreased from 2 to 22 h of the chase. This represents both the MGDG-DGDG precursor-product relationship of lipid synthesis (Li-Beisson et al., 2013) and the continual incorporation of labeled acyl groups into predominantly PC in the wild type, and into both PC and TAG in the HO line. Hence the apparent 32% decrease in MGDG accumulation in the HO line does not indicate that MGDG is turning over to feed the large increase in TAG accumulation; rather, it is the result of the labeled acyl group accumulation predominantly in TAG as more fatty acids are synthesized over the time course (Fig. 8). Therefore, the combined HO pulse-chase results indicate that TAG synthesis draws acyl groups predominantly from PC turnover (Fig. 9, B and D), which may compete with eukaryotic pathway MGDG synthesis for acyl groups (Table 3), but there does not appear to be evidence of galactolipid turnover providing substrates for TAG biosynthesis.

DISCUSSION

Biotechnology may help to meet societal needs by engineering metabolism to enhance the production of biological resources for food or industry. Plant lipids can be one part of this solution through increased oil yields per area of land for biofuel production. The current state of vegetative oil engineering involves the expression of only a few genes, including transcription factors to increase fatty acid synthesis, DGAT to convert DAG to TAG, and oleosin to prevent TAG breakdown in a push-pull-protect strategy (Vanhercke et al., 2014; Xu and Shanklin, 2016; Vanhercke et al., 2017). However, TAG biosynthesis requires many additional enzymatic steps that directly overlap with essential membrane lipid production (Fig. 1; Bates and Browse, 2012), and quantitative analysis of the oil end product does little to explain the metabolic path fatty acids take to accumulate in TAG. It is also unclear how an introduced DGAT fits into the leaf lipid metabolic network designed to accumulate ER and chloroplast membrane lipids, or which substrate pools are used in TAG biosynthesis (Fig. 1). For biofuel production, newly synthesized 18:1 could be directly incorporated into TAG with a minimal number of enzymatic steps using the Kennedy pathway (Fig. 1, option A), but this would not account for the presence of 18:2 and 18:3 measured in TAG. To understand the path of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network in wild-type tobacco leaves, and how the engineered changes in HO affect acyl flux, we analyzed the mechanisms of acyl flux in wild-type and HO leaves.

A Kennedy Pathway of TAG Assembly Is Not Present in HO Leaves

TAG composed of oleate is a desirable quality for biofuel production (Durrett et al., 2008). The least number of steps to incorporate oleate into TAG is directly through the Kennedy pathway reactions: G3P acyltransferase (GPAT) and lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAT) to produce PA, dephosphorylation by phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP) to produce DAG, and acylation of DAG to produce TAG (Fig. 1, option A; Bates, 2016). The large increase in 16:0 and 18:1 in HO TAG suggests that a Kennedy pathway utilizing newly synthesized fatty acids could produce at least some of the TAG in the HO line (Figs. 2 and 3). The only Kennedy pathway acyltransferase that was directly engineered into tobacco was AtDGAT1 (Vanhercke et al., 2014). Therefore, TAG fatty acid composition is also dependent on the acyl selectivity and substrate pools of the endogenous tobacco GPAT and LPAT. In vitro assays did not produce TAG with microsomes from either the wild type or the HO line (Fig. 4). This result may suggest that the four reactions of the Kennedy pathway in the HO line are not associated together in the isolated microsomes for efficient shuttling of substrates within the in vitro reactions. To further understand the path of acyl flux in wild-type and HO leaves we utilized an in vivo labeling approach.

Multiple lines of evidence from the in vivo labeling results suggest that a traditional Kennedy pathway is not the major pathway of TAG synthesis in HO leaves. First, even though fatty acids accumulate in HO TAG to a level 12 times that in PC (Fig. 2A), nascent fatty acids are incorporated into PC faster than into TAG (Fig. 5D). Second, during the pulse-chase, fatty acids are redistributed predominantly from PC into TAG (Fig. 9). Third, regiochemical analysis of de novo synthesized DAG indicated an equal partitioning of labeled acyl chains at both sn-1 and sn-2, whereas TAG contained nascent fatty acids only at sn-3 (Fig. 7). The regiochemical data indicates that de novo DAG produced by Kennedy-pathway GPAT/LPAT reactions (Fig. 1, option A) is not directly used for TAG biosynthesis. In combination with the in vitro assay, the results suggest that overexpressed AtDGAT1 does not produce a Kennedy pathway that channels newly synthesized fatty acids directly into TAG.

The results in this study are most consistent with option C in Figure 1 which indicates that a second pool of DAG (other than Kennedy-pathway de novo DAG) is used for TAG synthesis. It is not immediately clear how the second DAG pool is produced: it could be derived from de novo DAG, or PC, or a combination of the two. The pulse-chase results indicate that galactolipids, including MGDG, are not used for TAG production (Fig. 9). Thus, the reported mechanisms that turn over chloroplast lipids to produce DAG for leaf TAG under stress conditions (Vanhercke et al., 2019), are unlikely to actively contribute to TAG accumulation in HO tobacco leaves. Metabolic labeling with [14C]glycerol in developing oil seed tissues has suggested that a PC-derived DAG pool is utilized for TAG synthesis (Bates et al., 2009; Bates and Browse, 2011; Yang et al., 2017). The current [14C]acetate acyl labeling cannot directly confirm a PC-derived DAG pool, but the acyl labeling results are consistent with the previous studies. It is also possible that immediately synthesized de novo DAG may feed into a larger and slower-turnover DAG pool such as in oil bodies where AtDGAT1 may colocalize with oleosin proteins. DAG can phase partition into oil bodies (Slack et al., 1980; Kuerschner et al., 2008). Thus, if the rapidly labeled de novo DAG mixes with a larger unlabeled pool in the oil body it would slow the apparent flux of the sn-1/sn-2-labeled de novo DAG into TAG relative to the sn-3 TAG labeling of the total mixed DAG pool.

Both Wild-Type and HO Leaf Acyl Fluxes Are Dominated by PC Acyl Editing

In both wild-type and HO leaves, most newly synthesized fatty acids are immediately incorporated into PC (Fig. 5). The difference in stereochemical incorporation of newly synthesized fatty acid in DAG and PC (Fig. 7) indicates that there is no DAG-PC precursor-product relationship at the earliest labeling time points. PC labeling as a percent of ER lipid labeling (Fig. 6) at 3 min indicates that PC is 94.9 ± 1.5% of the total labeled ER lipids in the wild type, and 70 ± 4% in the HO line. The simplest interpretation of this result is a shift in acyl flux away from PC acyl editing in the HO line for direct incorporation of nascent fatty acids into the sn-3 position of TAG (Fig. 7). However, the production of TAG at heightened levels requires three acyl chains, of which a substantial percentage is PUFAs. Acyl editing is a constant exchange of acyl groups in PC with the acyl-CoA pool to accommodate desaturation. Thus, if the rate of acyl editing was increased in the HO line, a proportion of the labeled fatty acids initially incorporated into PC at time zero would be redistributed back to the acyl-CoA pool for use by AtDGAT1 to produce TAG within 3 min. This concept is supported with linear regression data used to determine labeling rates in Table 1. Extrapolating back to time zero, the x-intercepts of PC are 0.91 for the wild type, and 0.93 for HO. For TAG, the x-intercepts are 2.5 for the wild type, and 2.4 for HO. The similar labeling lag times between the wild type and the HO line suggest a common path of nascent fatty acid incorporation into ER lipids, though at a higher rate (1.7-fold) for the HO line (Fig. 6). Thus, the rate of acyl editing in the HO line was enhanced by the same amount (i.e. 1.7-fold) to accommodate the increased rate of fatty acid export from the plastid, and PC is the first product of nascent fatty acid incorporation into glycerolipids of the eukaryotic pathway.

The stereochemical distribution of labeled fatty acids in PC indicates that the initial incorporation of nascent fatty acids into PC can occur at both positions, but with an ∼2-fold preference for sn-2 (Fig. 7). The slightly higher PC sn-2 labeling in the HO line suggests that the increase in PC acyl editing favors sn-2 over sn-1 positions. Therefore, acyl flux around the PC acyl editing cycle (Fig. 1, option B) is the dominate acyl flux reaction in both wild-type and HO tobacco, similar to what has been demonstrated in leaves of pea, Arabidopsis, and rapeseed (Williams et al., 2000; Bates et al., 2007; Karki et al., 2019), and developing seeds of soybean, camelina, and Arabidopsis (Bates et al., 2009; Bates and Browse, 2011; Yang et al., 2017). Both PC acyl chains are the major extraplastidic sites for fatty acid desaturation (Sperling and Heinz, 1993; Sperling et al., 1993); therefore, 18:1 flux through PC acyl editing at both sn-1 and sn-2 likely contributes to a PUFA-containing acyl-CoA pool that leads to the incorporation of PUFA into TAG of HO leaves. The decrease in the PC desaturation index (Fig. 3C) is also consistent with an increased rate of acyl flux through PC, because membrane lipid desaturation is dependent on both the rate of desaturation and the rate of acyl flux through the membrane lipid. Increases in the fatty acid synthesis rate have been demonstrated to increase 18:1 and decrease PUFA content of membrane lipids (Maatta et al., 2012; Meï et al., 2015; Botella et al., 2016). Considering that the engineering of a very large pull of acyl chains into TAG in the HO line only increases PC acyl editing instead of drawing acyl chains away from it, PC acyl editing may be considered a key part of fatty acid export from the plastid into the eukaryotic pathway.

Interestingly, both the [14C]acetate continuous pulse and the pulse-chase experiments produced similar initial labeling in lipids for the wild type and the HO line (Figs. 6 and 8), but the pulse-chase experiment showed a more dramatic labeling in the immediate chase period in the HO line relative to the wild type (Fig. 8). Such a description of initial labeling is consistent with the hypothesized transport of acyl chains out of the chloroplast and directly into PC that subverts the large bulk acyl-CoA pool, as has been previously documented through bulk pool kinetic measurements with time-course labeling experiments (Tjellström et al., 2012; Allen, 2016b) and isotopically labeled mutant analysis (Bates et al., 2009; Karki et al., 2019), and is likely part of the acyl editing mechanism where rapid labeling in PC from [14C]acetate was initially observed (Bates et al., 2007, 2009). During the pulse-chase experiment, it may be that the bulk acyl-CoA pool in the HO line is larger and becomes more labeled over the duration of the pulse by enhanced flux through the acyl editing cycle, and therefore can make a greater contribution to total lipid labeling during the initial phase of chase.

Reduced Prokaryotic Pathway and Altered Redistribution of Acyl Chains from PC to Other Lipids in the HO Line

Engineering the accumulation of TAG in the HO line reduced the steady-state accumulation of chloroplast-localized galactolipids by ∼24% (Fig. 2). Total MGDG content in the HO line was reduced by ∼19%, and the proportion of prokaryotic pathway-produced MGDG was reduced by ∼40% (Supplemental Fig. S1). DGDG is produced mostly by eukaryotic pathway-derived substrates, and total DGDG levels were reduced by ∼32% in the HO line as compared to the wild type. Therefore, the mass accumulation of galactolipids indicates that TAG accumulation in the HO line negatively affects galactolipid production through both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways.

The reductions in galactolipid levels in the HO line could be due to reduced synthesis, increased turnover, or both, which cannot be determined from the quantification of steady-state lipid levels but is reflected in time course-based acyl flux experiments. At short time points, [14C]acetate labeling of nascent fatty acid flux into MGDG represents predominantly prokaryotic MGDG, which is reduced almost 5-fold in the HO line (Fig. 5; Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, the reduction in prokaryotic MGDG accumulation is primarily due to reduced synthesis. It’s also possible that homeostatic turnover of galactolipids was reduced to allow higher accumulation of MGDG than would be expected from the low rates of synthesis. To track the PC-MGDG precursor-product relationship of eukaryotic MGDG synthesis, we used pulse-chase analyses with longer time points. The [14C]acetate pulse-chase labeling indicated that the redistribution of acyl groups from PC in the HO line was predominantly into TAG, with reduced flux into eukaryotic MGDG synthesis as well as other lipids when compared to the wild type (Fig. 9; Table 3). As there was no reduction in total 14C-MGDG accumulation during the chase period in the HO line, the reduced eukaryotic MGDG accumulation was due to reduced redistribution of acyl groups from PC to MGDG through the eukaryotic pathway. Thus, there is no evidence to suggest enhanced galactolipid turnover in the HO line.

There are likely multiple alterations in enzymatic activity that led to the redistribution of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network in the HO line. From the acyl flux analysis, we can propose several related hypotheses for future studies. First, the massive increase in fatty acid accumulation in TAG of the HO line combined with the reduced prokaryotic pathway are likely both related to an increase in ACP thioesterase activity, which removes the substrate for the prokaryotic pathway and initiates fatty acid export from the chloroplast (Bates et al., 2013; Li-Beisson et al., 2013). The gene expression of both thioesterases FATA and FATB were up-regulated in the HO line (Vanhercke et al., 2017). The reduced prokaryotic pathway flux (Fig. 5, 9, Tables 2–3) combined with the reduced rates of MGDG desaturation in the HO line (Supplemental Figs. S5 and S6) also suggest a possible general down-regulation of prokaryotic pathway enzymatic activity.

Second, within the eukaryotic pathway, one-third of the fatty acids in TAG are incorporated into TAG directly from the acyl-CoA pool by the acyltransferase activity of the overexpressed AtDGAT1. In the wild type, the exchange of fatty acids from PC into the acyl-CoA pool would be mostly used for de novo glycerolipid synthesis that would produce the molecular species of PC used for eukaryotic galactolipid synthesis (Karki et al., 2019). Therefore, the increased flux around the PC acyl editing cycle combined with enhanced DGAT activity in the HO line would draw acyl flux away from PC and into sn-3 TAG, and would reduce the amount of fatty acids available for de novo PC and galactolipid synthesis.

Third, the reduction in eukaryotic galactolipid synthesis of the HO line may also be due to reduced turnover of PC to produce the PC-derived substrate for galactolipid synthesis, or to the commandeering of that PC-derived substrate for TAG biosynthesis. The identity of the eukaryotic pathway substrate that is transferred from the ER to the plastid is not clear, and leading candidates include PC, PC-derived PA, and/or DAG (Hurlock et al., 2014; LaBrant et al., 2018; Karki et al., 2019). If PC-derived DAG is the substrate that is transferred from the ER to the chloroplast for galactolipid synthesis, then the overexpressed AtDGAT1 may compete for the PC-derived DAG substrate in the ER and reduce its transfer to the chloroplast for eukaryotic galactolipid synthesis. However, if PA is the PC-derived species that is transferred to the chloroplast, then it would not be a substrate for AtDGAT1 activity unless PA phosphatase activity was also up-regulated to convert PA to DAG. Our previous transcriptomics in the HO line indicated increased expression of two phospholipase D isoforms that could produce PA from PC; however, an increase in PA phosphatase expression was not detected (Vanhercke et al., 2017). In Arabidopsis, the TRIGALACTOSYLDIACYLGLYCEROL 1 mutant (tgd1), or overexpression of PDAT1, increases wild-type leaf TAG content from <0.1% of dry weight to ∼0.5% and ∼1% of dry weight, respectively. Mutation of PA phosphatase activity in the PHOSPHATIDIC ACID HYDROLASE 1 and 2 double mutant (pah1 pah2) reduces this TAG accumulation in both the tgd1 and AtPDAT1 overexpression backgrounds, suggesting that PA phosphatase activity may be involved in leaf TAG production (Fan et al., 2014). However, the pah1 pah2 mutant has increased synthesis and twice the accumulation of leaf PC and PE content (Eastmond et al., 2010). In wild-type Arabidopsis leaves, PC and PE accumulate 5- to 10-fold more fatty acids than TAG (Fan et al., 2014); therefore the effect of the pah1 pah2 double mutation on leaf TAG accumulation in the tgd1 and AtPDAT1 overexpression lines may be due to a shift in fatty acid allocation from TAG to ER membrane lipids, rather than a reduction in TAG biosynthetic capacity. Therefore, the previous results in Arabidopsis and our transcriptomics have not fully elucidated the role of PA phosphatases in leaf TAG production. In addition, our analysis of acyl fluxes alone could not confirm whether or not the DAG pool for TAG synthesis was derived from PC. Therefore, further [14C]glycerol labeling experiments to confirm whether HO leaf TAG is derived from PC, combined with analysis of changes in PC lipase and PAP enzymatic activities, would be beneficial to determining both the altered pathway fluxes in the HO line, as well as identifying the PC-derived substrate that is used for eukaryotic galactolipid synthesis.

The Tobacco Leaf Acyl Flux Analysis Suggests Strategies to Reduce PUFA Accumulation in Leaf Oil

To reduce the PUFA content of oilseed crops, research has focused on reducing seed-specific FATTY ACID DESATURASE2 (FAD2) and FAD3 activity through mutations of isoforms mostly expressed in seeds but not vegetative tissue (Pham et al., 2010), or through seed-specific RNA interference (Wood et al., 2018; Islam et al., 2019). The purpose of the seed-specific reduction in desaturase activity is to increase the oleate content of the seed oil but not affect leaf membrane lipid compositions in vegetative tissue. ER membrane-based FAD2 activity is required for proper leaf membrane function, especially at low temperatures (Miquel et al., 1993). Due to the importance of leaf desaturases for vegetative growth, a similar reduction of desaturase activity would likely be counterproductive in a vegetative oil crop. The analysis of acyl fluxes in wild-type and HO tobacco leaves presented here indicates that fatty acid flux through the PC acyl-editing cycle is the dominate reaction in the wild type, and is enhanced at least 1.7-fold in the HO line. Because PC is the site for ER-localized fatty acid desaturation, this movement of acyl groups through PC contributes to accumulation of PUFAs in HO leaf TAG. Therefore, an alternative strategy may be to alter acyl flux away from PC. In Arabidopsis, the LYSOPHOSPHATIDYLCHOLINE ACYLTRANSFERASEs (LPCAT1 and LPCAT2) are responsible for the direct incorporation of nascent fatty acids into PC through acyl editing in both leaves (Karki et al., 2019) and seeds (Bates et al., 2012). The lpcat1 lpcat2 double mutant alters acyl flux such that nascent fatty acids are first esterified into glycerol lipids through the GPAT and LPAT reactions of the Kennedy pathway rather than PC acyl editing (Bates et al., 2012; Karki et al., 2019). In seeds, this leads to an increase in the seed oil monounsaturated/polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio from 0.72 to 0.84. When reduced exchange of DAG in and out of PC of the PHOSPHATIDYLCHOLINE: DIACYLGLYCEROL CHOLINEPHOSPHOTRANSFERASE mutant rod1 is combined with the lpcat1 lpcat2 double mutant, the ratio is further increased to 3.95 in the lpcat1 lpcat2 rod1 triple mutant (Bates et al., 2012). It was unclear from our current analysis whether leaf TAG was produced from PC-derived DAG, but if PC-derived DAG also contributes to leaf TAG, a similar approach reducing acyl editing and PC-derived DAG production may be valuable to alter acyl flux around PC to increase the oleate content of leaf TAG while maintaining the PUFA content of membranes. Therefore, the acyl flux analysis presented here has improved our understanding of how leaf lipid metabolism responds to an increased push and pull of fatty acids into TAG, and has provided new hypotheses on how to further enhance vegetative oil engineering.

In summary the analysis of acyl fluxes in wild-type and HO tobacco leaves indicates the following. (1) The push-and-pull leaf oil production in the HO line reduces acyl flux into the prokaryotic pathway and enhances flux into the eukaryotic glycerolipid assembly pathways. (2) Fatty acids entering the eukaryotic pathway are first incorporated into PC through acyl editing in both wild-type and HO tobacco plants. (3) The high flux of nascent acyl groups directly into PC acyl editing and the initial labeled TAG regiochemical analysis both indicate that a direct Kennedy pathway of TAG biosynthesis with nascent fatty acids does not occur in HO leaves. (4) In HO leaves, acyl groups are redistributed from PC mostly into TAG, rather than into eukaryotic MGDG production as in the wild type. (5) The enhanced flux of fatty acids into TAG combined with the reduced flux of fatty acids into both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways of galactolipid synthesis reduced the steady-state accumulation of MGDG and DGDG. (6) The pulse-chase did not indicate TAG synthesis from galactolipid turnover. (7) Characterization of the high rates of PC acyl editing in the HO line suggests that limiting PC acyl editing may be a future engineering strategy to increase the monounsaturated fatty acid content of leaf-derived biofuels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth

For lipid mass analysis and metabolic labeling experiments, wild-type and HO tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants were grown in Percival E-41HO growth chambers set at 16 h light/8 h dark, 26°C/22°C, and fluorescent white light intensity at pot level across the chamber was 300–400 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Pots were watered three times a week, with one watering replaced by Peters 20/20/20 NPK fertilizer at 0.97 g/L. For microsomal assays, tobacco plants were grown in the glasshouse in summer conditions at 24°C/18°C for 16 h light/8 h dark.

Chemicals and Supplies

Unless specified, all chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (www.fishersci.com), and solvents were at least HPLC grade. [14C]acetate sodium salt 50 mCi/mmol was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. Glass thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (hard-layer 250 µm, 20 × 20 cm) were from Analtech. The liquid scintillation fluid was EcoScint Original (National Diagnostics). Lipase from Rhizomucor miehei and phospholipase A2 from Apis mellifera were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Microsomal Assays

Leaves were harvested from 66-d-old tobacco plants, and the microsomal proteins were prepared as described (Zhou et al., 2013). Protein content of the microsomal preparations was measured with bicinchoninic acid reagents (Pierce Chemical Company), with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The enzyme assay was essentially done as described (Guan et al., 2014). Microsomal proteins (100 µg) were incubated at 30°C with gentle shaking in 0.1 m Tris buffer, pH 7.2, containing 4 mm MgCl2, 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 12.5 nmol [14C]G3P (8,000 DPM/nmol), and 25 nmol 18:1-CoA in a final assay volume of 100 µL for 15 or 60 min. The assays were terminated by addition of 250 µL of methanol/chloroform/acetic acid (50:50:1 [v/v/v]), followed by extraction of the lipids into a chloroform phase. The total lipids were separated on silica TLC plates by developing first with chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/water (90:15:10:3 [v/v/v/v]) to halfway up the plate to separate the polar lipids. After air drying for a few minutes, the plates were redeveloped with hexane/diethyl either/acetic acid, 70:30:1 (v/v/v), to separate the neutral lipids. Radioactive labels of 1,000 DPM were spotted three times on each plate as reference before exposing to a phosphor image screen overnight. The radioactivity of each band was quantified with Fujifilm FLA-5000 Phosphor Imager.

Continuous Pulse and Pulse-Chase [14C]Acetate Metabolic Labeling

The continuous-pulse metabolic labeling of wild-type and HO leaf disks was done for 3, 6, 10, 30, and 120 min in triplicate, in 20 mm MES, pH 5.5, 0.1× Murashige and Skoog salts, 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20, and 1 mm [14C]acetate. The labeling procedure involved collecting 10-mm-diameter leaf disks from multiple plants (two wild-type plants and three HO plants) randomized across all horizontal leaves. For each time point replicate, 12 disks were collected directly into 10 mL incubation media (without [14C]acetate) in 100 mL beakers and placed in a 26°C water bath under ∼330 µmol photons m−2 s−1 white light with gentle shaking for 10 min to equilibrate temperature. To start the labeling time course, the medium was removed and replaced with 5 mL of incubation medium with [14C]acetate. At each time point, the medium was removed and the 12 leaf disks were placed into 85°C 2.5 mL isopropanol and 0.01% (w/v) butylated hydroxytoluene for 10 min to quench metabolism. Each replicate time course for each plant line used three 5-mL aliquots of 1 mm [14C]acetate labeling media. The remaining [14C]acetate medium after the 6-min time point was used for the 120-min labeling, and the remaining medium from the 10-min time point was used for the 30-min labeling. The remaining [14C]acetate media from the 3-min and 10-/30-min labeling time points were mixed and used for the pulse-chase [14C]acetate labeling.

For each of the triplicate pulse-chase labeling time courses, 24 leaf disks were collected as described above and pulsed with [14C]acetate labeling media independently for 30 min. The 14C media was removed, the disks were washed three times in media without [14C]acetate (10 mL each time), and a final 10 mL media was added for chase incubations. At each chase time point of 0, 2, 6, and 22 h, six leaf disks were collected from each time course incubation and quenched as described above.

Lipid Extraction and Lipid Class TLC Separations

Lipids were extracted from isopropanol-quenched tissue following a previous method (Hara and Radin, 1978). After drying total extracts under N2, lipids of each extract were dissolved in 0.5 mL toluene and aliquots were used for various analytical procedures. Total 14C extracts were quantified by liquid scintillation counting on a Beckman Coulter LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter. Neutral lipids were separated on silica TLC plates in hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid, 70:30:1 (v/v/v). Polar lipids were resolved with toluene/acetone/water (30/91/7, v/v/v) on silica TLC plates pretreated with 0.15 m ammonium sulfate and baked at 120°C for 3 h prior to loading lipids. Lipid classes were identified based on comigration with standards. Relative radioactivity of lipids separated by TLC was measured by phosphor imaging on a Typhoon FLA7000 (GE Healthcare) and using ImageQuant analysis software.

Leaf Lipid Mass Analysis

Leaf lipids extracted from 86-d-old plants were separated by TLC as described above and stained with 0.05% primulin in acetone/water 80:20 (v/v) and visualized under UV light. Scraped bands were transmethylated along with a 17:0 TAG internal standard of FAMEs in 2.5% (v/v) sulfuric acid in methanol at 80°C for 1 h. FAMEs were collected into hexane by adding hexane and 0.88% (w/v) NaCl to force a phase separation. FAMEs were separated and quantified by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection on a Restek Stabilwax column (30 m, 0.25 inner diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness).

Regiochemical Analysis of DAG, PC, and TAG

Total lipids extracted as described above from the wild type and the HO line were coloaded with 30 µg PC and 30 µg DAG. For the wild type, 30 µg TAG was also coloaded. Polar lipid and neutral lipid TLC and primulin staining were performed as described above. PC bands were scraped off and eluted with chloroform/methanol/water (5:5:1 [v/v/v]). Partial digestion of PC was performed with bee venom (Apis mellifera) phospholipase PLA2 (Sigma; Bates et al., 2007). The digested products were separated by TLC in chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/water 50:30:8:4 (v/v/v/v). Regiochemical analysis of neutral lipids was performed as described in Cahoon et al. (2006). DAG and TAG were digested with 0.2 mL of the Rhizomucor meihei lipase (Sigma) for 30 and 60 min, respectively. Digested products were separated by TLC in hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (35:70:1 [v/v/v]). Lipid standards were stained with iodine vapor and marked with 14C. Identification of unknowns was based on comigration with standards. Radioactivity was quantified using phosphor imaging, as described in the section “Lipid Extraction and Lipid Class TLC Separations”.

Analysis of [14C]Acetate-Labeled MGDG Molecular Species

MGDG was isolated by normal-phase HPLC on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II equipped with a quaternary pump, autosampler, column thermostat, DAD set to 210 nm, and fraction collector (running OpenLAB CDS Version C.01.09). The method is an adaption of Kotapati and Bates (2018), with modifications as follows: the injection volume was 5–15 µL in toluene; the flow rate was 1 mL/min; and mobile phases were 2-propanol (A), hexanes (B), methanol (C), and 25 mm triethylamine + 25 mm formic acid (pH 4.1). Linear gradients between steps were as follows: 0 min, 19.3%A/80%B/0.5%C/0.20%D; 3 min, 73.6%A/25%B/1%C/0.4%D; 6 min, 87.5%A/10%B/1.5%C/1%D; 15 min, 65%A/0%B/25%C/10%D; held for 3 min; 20 min, 100%A; held for 3 min; 24 min is back to the starting composition, and equilibration between samples is 10 min. MGDG was collected between 5.3 and 6.2 min. MGDG molecular species were separated by HPLC on a Thermo Scientific Accucore C18 column (150 mm × 3 mm; 2.6 µm particle size), according to the methods of Yamauchi et al. (1982), except that the flow rate was 0.35 mL/min for 35 min. The vial sampler was maintained at 20°C and the column compartment at 35°C. Samples were injected in 8–15 µL methanol and contained 5,000–20,000 CPM. To measure radioactivity, the column eluent flowed into a LabLogic β-Ram 6 flow liquid scintillation detector; flow cell volume was set at 300 µL, and the eluent:scintillation cocktail (LabLogic FloLogic-U) ratio was 1:3, with a residence time of 12.9 s. Laura 6.0.1.40 software was used to acquire and process the 14C data. To confirm the identity of labeled molecular species, each fraction was collected, converted to FAME as above, and separated by argentation TLC, as in Bates et al. (2009).

Data Analysis

All calculations from raw data were done in Microsoft Excel. Graphing and statistical analysis were done with GraphPad Prism version 7.05.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AT3G54320 (AtWRI1); AT2G19450 (AtDGAT1); SiOLEOSIN; EU999158; AT3G12120 (AtFAD2); AT2G29980 (AtFAD3); AT1G12640 (AtLPCAT1); AT1G63050 (AtLPCAT2); AT3G09560 (AtPAH1); AT5G42870 (AtPAH2); AT5G13640 (AtPDAT1); AT3G15820 (AtROD1); and AT1G19800 (AtTGD1).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Stereochemical fatty acid composition of MGDG and DGDG from wild type and HO leaves.

Supplemental Figure S2. Total incorporation of [14C]acetate into wild type and HO leaves.

Supplemental Figure S3. Initial incorporation of nascent [14C]acetate labeled fatty acids into lipids, nonnormalized.

Supplemental Figure S4. Example of 14C-MGDG molecular species analysis.

Supplemental Figure S5. Labeled MGDG molecular species from 30 and 120 min continuous [14C]acetate labeling.

Supplemental Figure S6. Labeled MGDG molecular species from 0 and 22 h pulse-chase [14C]acetate labeling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bei Dong for technical support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (grant nos. 2017-67013-26156, 2017-67013-29481, and Hatch umbrella project no. 1015621), and the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1930559).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Allen DK. (2016a) Assessing compartmentalized flux in lipid metabolism with isotopes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861(9 Pt B): 1226–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DK. (2016b) Quantifying plant phenotypes with isotopic labeling & metabolic flux analysis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 37: 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DK, Bates PD, Tjellström H (2015) Tracking the metabolic pulse of plant lipid production with isotopic labeling and flux analyses: Past, present and future. Prog Lipid Res 58: 97–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arisz SA, Heo J-Y, Koevoets IT, Zhao T, van Egmond P, Meyer AJ, Zeng W, Niu X, Wang B, Mitchell-Olds T, et al. (2018) DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE1 contributes to freezing tolerance. Plant Physiol 177: 1410–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafor M, Smith MA, Jonsson L, Stobart K, Stymne S (1991) Ricinoleic acid biosynthesis and triacylglycerol assembly in microsomal preparations from developing castor-bean (Ricinus communis) endosperm. Biochem J 280: 507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron EJ, Stumpf PK (1962) Fat metabolism in higher plants. XIX. The biosynthesis of triglycerides by avocado-mesocarp enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 60: 329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD. (2016) Understanding the control of acyl flux through the lipid metabolic network of plant oil biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861(9 Pt B): 1214–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Browse J (2011) The pathway of triacylglycerol synthesis through phosphatidylcholine in Arabidopsis produces a bottleneck for the accumulation of unusual fatty acids in transgenic seeds. Plant J 68: 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Browse J (2012) The significance of different diacylgycerol synthesis pathways on plant oil composition and bioengineering. Front Plant Sci 3: 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Durrett TP, Ohlrogge JB, Pollard M (2009) Analysis of acyl fluxes through multiple pathways of triacylglycerol synthesis in developing soybean embryos. Plant Physiol 150: 55–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Fatihi A, Snapp AR, Carlsson AS, Browse J, Lu C (2012) Acyl editing and headgroup exchange are the major mechanisms that direct polyunsaturated fatty acid flux into triacylglycerols. Plant Physiol 160: 1530–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Ohlrogge JB, Pollard M (2007) Incorporation of newly synthesized fatty acids into cytosolic glycerolipids in pea leaves occurs via acyl editing. J Biol Chem 282: 31206–31216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates PD, Stymne S, Ohlrogge J (2013) Biochemical pathways in seed oil synthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella C, Sautron E, Boudiere L, Michaud M, Dubots E, Yamaryo-Botté Y, Albrieux C, Marechal E, Block MA, Jouhet J (2016) ALA10, a phospholipid flippase, controls FAD2/FAD3 desaturation of phosphatidylcholine in the ER and affects chloroplast lipid composition in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 170: 1300–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J, Warwick N, Somerville CR, Slack CR (1986) Fluxes through the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways of lipid synthesis in the “16:3” plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem J 235: 25–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon EB, Dietrich CR, Meyer K, Damude HG, Dyer JM, Kinney AJ (2006) Conjugated fatty acids accumulate to high levels in phospholipids of metabolically engineered soybean and Arabidopsis seeds. Phytochemistry 67: 1166–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson AS, Yilmaz JL, Green AG, Stymne S, Hofvander P (2011) Replacing fossil oil with fresh oil—With what and for what? Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 113: 812–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernac A, Benning C (2004) WRINKLED1 encodes an AP2/EREB domain protein involved in the control of storage compound biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 40: 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrett TP, Benning C, Ohlrogge J (2008) Plant triacylglycerols as feedstocks for the production of biofuels. Plant J 54: 593–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ, Quettier A-L, Kroon JTM, Craddock C, Adams N, Slabas AR (2010) Phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 and 2 regulate phospholipid synthesis at the endoplasmic reticulum in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22: 2796–2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]