The phloem-limited Gram-negative bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus interacts with the phloem membranes of citrus species and can change its form to move through the phloem pores.

Abstract

Citrus greening or Huanglongbing (HLB) is caused by the phloem-limited intracellular Gram-negative bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas). HLB-infected citrus phloem cells undergo structural modifications that include cell wall thickening, callose and phloem protein induction, and cellular plugging. However, very little is known about the intracellular mechanisms that take place during CLas cell-to-cell movement. Here, we show that CLas movement through phloem pores of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) and grapefruit (Citrus paradisi) is carried out by the elongated form of the bacteria. The round form of CLas is too large to move, but can change its morphology to enable its movement. CLas cells adhere to the plasma membrane of the phloem cells specifically adjacent to the sieve pores. Remarkably, CLas was present in both mature sieve element cells and nucleated nonsieve element cells. The sieve plate plugging structures of host plants were shown to have different composition in different citrus tissues. Callose deposition was the main plugging mechanism in the HLB-infected flush, where it reduced the open space of the pores. In the roots, pores were surrounded by dark extracellular material, with very little accumulation of callose. The expression of CALLOSE SYNTHASE7 and PHLOEM PROTEIN2 genes was upregulated in the shoots, but downregulated in root tissues. In seed coats, no phloem occlusion was observed, and CLas accumulated to high levels. Our results provide insight into the cellular mechanisms of Gram-negative bacterial cell-to-cell movement in plant phloem.

Citrus greening, or Huanglongbing (HLB), is the most devastating disease of citrus. The disease is caused by the Gram-negative phloem-limited bacteria Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas), Candidatus Liberibacter africanus, and Candidatus Liberibacter americanus. CLas is found in Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, the United States, Cuba, Mexico, West Indies, Honduras, and Brazil, and it is exclusively transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri. Fruits from infected trees are green, misshapen, and bitter (Bove, 2006). Disease symptoms include blotchy mottled leaves (nonsymmetrical chlorosis or mottling), pale yellow leaves, yellow shoots, corky veins, stunting, and twig dieback. Roots are also affected, with dramatic decreases observed in the mass of fibrous roots in infected plants (Johnson et al., 2014). In leaves, another phenotype associated with HLB is the accumulation of callose inside the sieve plate pores of the infected plant’s phloem. Accumulation of callose was demonstrated both by aniline blue staining and by immunogold labeling (Kim et al., 2009; Achor et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2019; Granato et al., 2019). This accumulation is an early response that begins at early stages of the disease and probably leads, at more advanced disease stages, to collapse of the cells. An associated third disease symptom is the accumulation of excessive amounts of starch in the leaves of infected plants (Kim et al., 2009; Achor et al., 2010; Granato et al., 2019). This phenotype is not observed in the roots (Kim et al., 2009; Etxeberria et al., 2009; Folimonova and Achor, 2010). It was shown that the accumulation of starch occurs only after the accumulation of callose in the sieve elements and after the collapse of phloem cells. Leaf chlorosis was related to the disruption of the cell inner grana structure and happened only in parts of the leaf where plugging of the phloem occurred (Achor et al., 2010). These phenotypes raised the hypothesis that the blotchy mottled leaf symptom, and the damage caused to the fruits, result from the plugging of the phloem cells, leading to decreased translocation of sugar and the accumulation of starch in the source tissues. Unplugging the phloem may therefore provide an attractive way to increase the productivity of affected plants. Association of callose with sieve areas and sieve plates in angiosperms has been widely studied (Behnke and Sjolund, 1990; Stone and Clarke, 1992). Induced phloem callose led to a decrease in the lateral movement of C14-assimilates and auxin, whereas treatments that stimulate breakdown of sieve plate callose led to increased movement of fluorescein through the sieve tubes (Webster and Currier, 1965; McNairn and Currier, 1968; Hollis and Tepper, 1971; McNairn, 1972; Aloni et al., 1991; Maeda et al., 2006). In citrus leaves, callose accumulation during CLas infection impaired symplastic dye movement into the vascular tissue and inhibited photoassimilate export in the infected leaves (Koh et al., 2012). On the other hand, a phloem-specific callose synthase (CALLOSE SYNTHASE7 [CalS7]) was recently identified, and its absence resulted in carbohydrate starvation (Barratt et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2011; Xie and Hong, 2011). These results suggest that the presence of basal levels of callose may actually be required for efficient carbohydrate transport in the phloem and pointed to a more complex relationship between sieve pore callose and phloem transport, where the balance is important and either too much or too little callose can have a negative effect.

An additional mechanism for phloem plugging that was also shown to occur in HLB-infected plants is the induction of phloem proteins (P-proteins). These gel-forming proteins were shown to undergo a rearrangement in the sieve elements after injury or irradiation (Knoblauch and van Bel, 1998; Knoblauch et al., 2001). These proteins are suggested to play a role in plugging of sieve plates to maintain turgor pressure within the sieve tube after injury and during pathogen and pest infection, but their exact role in these processes is still unclear (Knoblauch et al., 2014). In Cucurbita spp., two predominant P-proteins, the phloem filament protein or PHLOEM PROTEIN1 (PP1) and the phloem lectin or PP2, have been associated with the structural P-protein filaments. PP2 is a dimeric poly-GlcNAc-binding lectin that was shown to be covalently linked to P-protein filaments by disulfide bridges (Read and Northcote, 1983). In HLB-infected sweet orange plants, sieve elements were obstructed by filamentous protein material and it was shown that the plugging material contained PP2 by immunogold labeling (Achor et al., 2010). PP2 gene expression was also shown to be upregulated in leaves of HLB-infected sweet orange plants compared to healthy plants (Kim et al., 2009). Moreover, PP2 transcript levels were also upregulated in an HLB-susceptible citrus variety compared to that in a tolerant variety, suggesting that PP2 expression and phloem plugging may play a role in the onset of disease symptoms in susceptible varieties (Wang et al., 2016).

Whereas complete plugging of the phloem cells was clearly demonstrated, very little is currently known regarding sieve pore closure and the intra- and intercellular movement of CLas between sieve tubes. Here, we focused on the cellular processes that take place at the phloem pores. By examining the ultrastructure of the phloem pores and the movement of CLas in the infected sink citrus tissues of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) and grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), we show that whereas sieve pores are plugged by callose in cells of young leaves, the callose is not induced in the fibrous roots and seed coats. In the unplugged sieve elements, we show that CLas can move between cells and that the bacterium’s ability to change its morphology enables it to enter the pores. We also show that CLas can move into nucleated cells in the seed coat phloem tissue, whose identity is still unknown. Finally, we show that CLas is associated with the phloem pores via adhesion to the plasma membrane adjacent to them. This interaction may target CLas to the pores and play a role in the cell-to-cell movement of the bacteria.

RESULTS

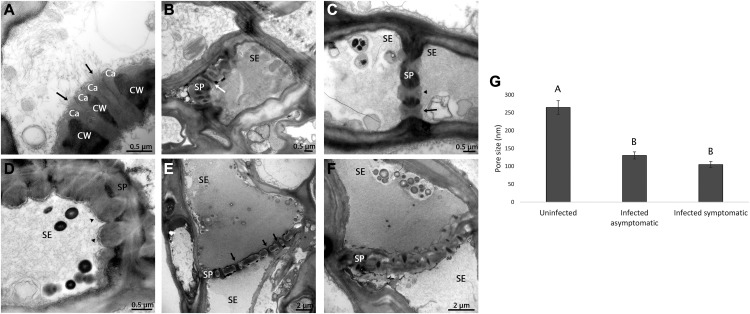

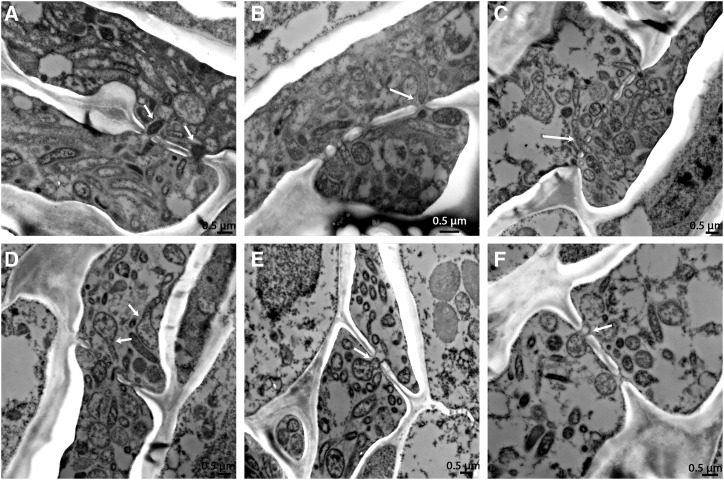

In the Flush, Sieve Pore Size Is Reduced by Callose

It was previously shown that in HLB-susceptible sweet orange and grapefruit, CLas infection leads to dramatic phloem phenotypes such as the swelling of the middle lamella between cells surrounding sieve elements and the complete plugging of phloem sieve tubes by a P-protein–like material (Folimonova and Achor, 2010; Supplemental Fig. S1, A–C). In this study, our focus was to analyze the sieve pore characteristics in the cells that are still functional (not completely plugged or collapsed) and to determine whether CLas can move between these cells. Because CLas accumulates in the phloem, we hypothesized that CLas moves mainly with the phloem flow and, thus, will accumulate in higher numbers in the sink tissues. We, therefore, focused on three sink tissues: the young leaves (flush), the emerging fibrous roots, and the seed coats of developing seeds. We used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to further analyze the phloem at the ultrastructural level in Madame Vinous sweet orange and Duncan grapefruit. We first examined phloem cells from the young developing leaves (flush). The TEM images clearly revealed the ultrastructure of the pores, including the presence of callose and filamentous protein inside the pores (Fig. 1A). In TEM sections of uninfected sieve pores, we observed a basal level of callose, which partially reduced their opening, but clearly left available space for movement between cells (Fig. 1B). The average opening of the pores in uninfected plants flush was 265 ± 19 nm. Such an opening is similar to the described average width of CLas (Hilf et al., 2013). The callose we observed may be, in part, a result of our tissue preparation procedure. In sections collected from HLB-infected flush tissues, results were dramatically different. In many sieve plates, callose accumulated to a much higher level and almost completely filled the space of the pores, leaving no available space for movement (Fig. 1, C–F). Callose levels in the cells were variable. In some cells, we could detect a combination of open and occluded pores (Fig. 1C), whereas in the other cells callose completely filled the cell and plugged the whole sieve area (Fig. 1D). On average, opening diameters were about half of what was found in uninfected plants, with no difference between asymptomatic and symptomatic plants: The average pore opening was 130 ± 10 nm for infected asymptomatic and 105 ± 9 nm for infected symptomatic cells (Fig. 1G). Similar results were obtained from grapefruit (275 ± 30nm for healthy and 174 ± 20 nm for infected plants). Remarkably, we saw very few CLas bacterial cells in the images generated from the flush (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phloem pore plugging in HLB-infected flush. A to F, TEM micrographs of sieve plates in Madam Vinous sweet orange flush. Arrows indicate open pores, whereas arrowheads indicate a blocked pore. A, High-magnification image showing sieve pore structure. Arrows are pointing at two pores. Callose(Ca) is the lighter-color material present next to the cell wall (CW) along the pores. B to D, Cross section of sieve plates (SP). B, Open pores in uninfected plants. Pores contain callose, but an open pathway is clear (arrow). C, Mixed situation in an infected asymptomatic plant. Some pores are open (arrows) whereas others are occluded (arrowhead). D, Completely sealed pores in infected symptomatic plant (arrowheads). E and F, Longitudinal sections of sieve plates, showing the accumulation of either low levels (E) or high levels (F) of callose. G, Average opening size of sieve plate pores in uninfected, infected asymptomatic, and infected symptomatic sweet orange flush. Different letters indicate statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001; Tukey’s honestly significant difference). Error bars are se, N (uninfected) = 77, N (infected asymptomatic) = 159 and N (infected symptomatic) = 119. SE, sieve elements.

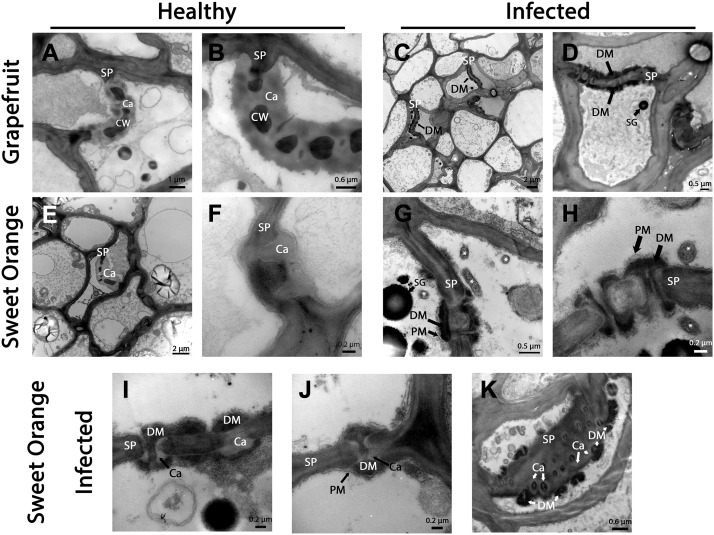

In Roots, Pores Are Plugged by an Alternative Mechanism

Next, we examined the sieve pores in young fibrous root tissues in Madame Vinous and Valencia sweet orange and in Duncan grapefruit. In TEM sections from uninfected roots, callose could be seen in the pores of the phloem (Fig. 2, A, B, E, and F). As was previously shown, thickening and collapse was observed in infected root sieve elements, similar to that in the flush (Aritua et al., 2013; Supplemental Fig. S1D). However, in the noncollapsed cells of HLB-infected root tissues, very little callose was seen. Instead, we consistently detected the accumulation of dark extracellular material along the phloem pores (Fig. 2, C, D, G, and H). This accumulated material differed in its consistency and color from the healthy tissues callose (Fig. 2), and was deposited extracellularly between the plasma membrane and the cell wall (Fig. 2, G and H), which is different from the filamentous P-protein we observed inside the pores of the flush (Fig. 1A) and from the material that was previously shown to bind with PP2 antibody (Achor et al., 2010). These deposits accumulated at the openings of the phloem pores and inside the pores (Fig. 2, H–J). The dark extracellular material was detected in grapefruit and sweet orange (both Valencia and Madame Vinous), but we never detected it in phloem from infected flush or from roots of healthy plants that were identically stained (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, we could rule out the possibility that this dark material was a callose-staining artifact, because we could observe it at the pores in addition to the brighter and smoother thin callose collar (Fig. 2, I–K). Unlike the flush, in the roots we could find the CLas bacteria associated with the phloem, but the number of the bacterial cells was still relatively low (Fig. 2, G and H). In some cases, we could detect CLas attaching to the cell membrane, with the extracellular deposits accumulating adjacent to CLas attachment place (Fig. 2H).

Figure 2.

Phloem plugging in HLB-infected roots. A to K, TEM images of sieve area in healthy (A, B, E, and F) and HLB-infected (C, D, G, and K) roots of Duncan grapefruit (A–D), Valencia sweet orange (E–H), and Madame Vinous sweet orange (I–K). A, B, E, and F, Sieve pores (SP) of healthy grapefruit and sweet orange containing callose (Ca) next to the darker cell wall (CW) along the pores. C, D, G, and H, Sieve pores of grapefruit and sweet orange HLB-infected plants mainly contain extracellular deposits of a dark material (DM). These deposits are formed between the plasma membrane (pm) and the pore cell wall. Sieve elements also contain starch granules (SG). CLas cells are marked with an asterisk (*). I to K, Deposited dark material together with thin collars of callose in sieve pores from infected sweet orange.

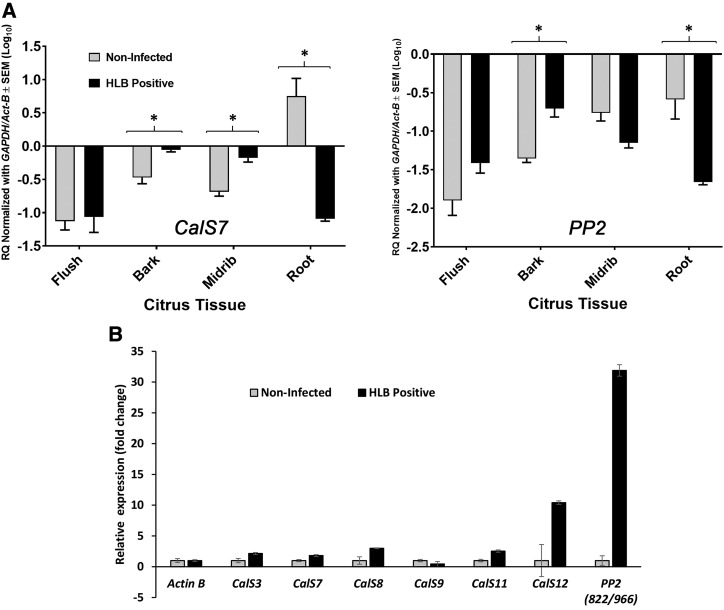

To provide supporting evidence for the differential plugging dynamics observed between the shoots and the roots in the microscopy images, we also conducted gene expression analyses for the phloem-localized PP2 and CalS7 genes. Samples were collected from the flush, bark, mature-leaf midribs, and roots of both healthy and infected plants, and the gene expression levels in HLB-infected tissues were compared to those in the same tissues of healthy plants (Fig. 3A). As expected, the expression levels of both CalS7 and PP2 were upregulated in almost all the CLas-infected shoot tissues, the only exception being PP2 expression in midribs. CalS7 expression levels were significantly upregulated in HLB-infected bark and midribs, and for PP2, there was a significant upregulation in the bark tissues. In sharp contrast to the shoot tissues, the expression levels of both CalS7 and PP2 were significantly downregulated in HLB-infected roots compared to healthy roots. For PP2, there was a 5-fold downregulation in the roots, and for CalS7 there was a strong 100-fold downregulation in the roots of infected plants compared to the roots of healthy plants. To verify that CalS and PP2 genes were expressed in grapefruit vasculature, and to further explore if there are additional phloem-related grapefruit orthologs of these families, we isolated RNA from the lateral veins of healthy and infected blotchy mottled leaves and compared gene expression levels of the different gene family members. CalS3, CalS7, CalS8, CalS9, CalS11, and CalS12 were all expressed in the lateral leaf vein, but there was no expression of CalS2, CalS5, and CalS10 detected, indicating these three family members are not phloem-related in grapefruit (Fig. 3B). For PP2, we could not detect any expression for orange1.1g041394m, orange1.1g045187m, orange1.1g042480m, and the orange1.1g039003m PP2 homologous transcripts. The only primer pairs that detected gene expression in the veins were designed for orange1.1g024966m and orange1.1g024822m (Fig. 3B). These two sweet orange transcripts share 90% identity and may represent a single PP2 family member.

Figure 3.

CalS and PP2 gene expression analyses. A, RQ of CalS7 and PP2 transcripts normalized with GAPDH and ActB reference genes, in different tissues of noninfected and HLB-infected Citrus macrophylla plants. Comparisons with asterisk (*) indicates significant difference (P < 0.05; multiple Student’s t test). B, CalS and PP2 gene expression in lateral veins of healthy and CLas-infected (blotchy mottled) Duncan grapefruit leaves. Transcripts normalized with ActB reference gene. Error bars are se, n = 3.

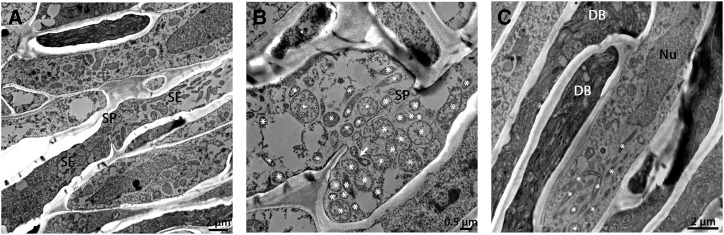

In Seed Coats, Open Pores Enable Widespread Cell-to-Cell Movement of CLas

TEM sections from the phloem tissue in the chalazal end of young seed coats (Hilf et al., 2013) showed a dramatically different situation than what was seen in both the plant roots and shoots. In Valencia sweet orange seed coats, cells were almost free of callose, and phloem pores remained open, with an average available space of 332 ± 14 nm for cell-to-cell movement (Fig. 4, A and B). Inside these cells, bacteria accumulated to very high numbers, sometimes filling all the available space inside the cells, and were clearly dividing and propagating (Fig. 4). Bacteria appeared as both round and elongated bacilliform-like shapes, characteristic of CLas (Hilf et al., 2013). Similar results were observed in grapefruit seed coats, where we detected only moderate levels of callose that was comparable to healthy seed coats, indicating that only normal callose levels are present in infected tissue without further accumulation (Supplemental Fig. S2). In the infected Duncan grapefruit seed coats, we could detect high levels of CLas bacterial cells as well, some of which were entering or exiting the sieve pores (Supplemental Fig. S2). Remarkably, in both sweet orange and grapefruit seed coat tissues, we could clearly detect CLas in living nucleated cells (nonsieve element cells; Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S2). The nature of these nonsieve elements cells and the possible bacteria movement mechanisms into them are still unclear.

Figure 4.

Phloem pores in HLB-infected seed coats. A to C, TEM images of phloem and sieve plates in HLB-infected sweet orange seed coats. A, Phloem sieve elements (se) are filled with CLas bacteria with open sieve plates (SP) pores. B, Higher magnification of the sieve plate. CLas bacterial cells (marked with asterisks [*]), including dividing bacteria (marked by arrow), are present, and pores are open. C, Seed coat phloem. Very high numbers of bacterial cells are found, even inside nucleated cells (bacteria marked with asterisks). In addition, some cells are full of deteriorating bacteria (DB). Nu, nucleus.

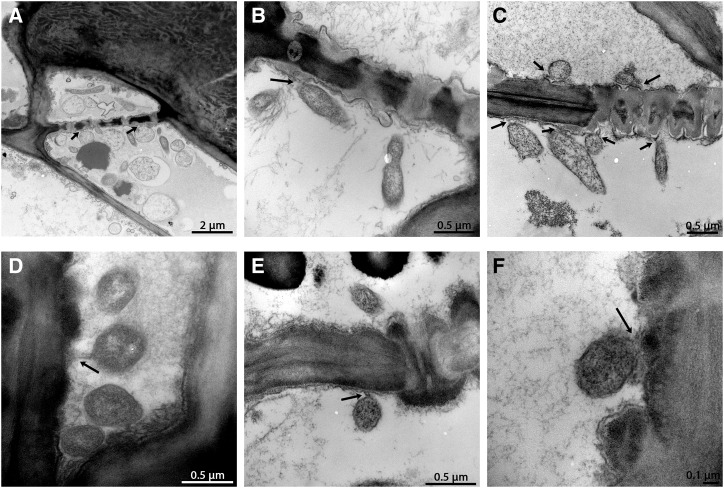

The open sieve pores enabled CLas bacteria to move between cells (Fig. 5, A–C). The size of these open pores (average 332 ± 14 nm) were shown to fit perfectly with the diameter of the elongated form of CLas (Fig. 5C). Remarkably, this elongated form usually reached the pores in the right orientation for movement (perpendicularly to the plasma membrane; Fig. 5, B and C), suggesting an unknown targeting mechanism may be involved. Once at the sieve pores, the elongated bacteria could move, cross the sieve pores, and enter the adjacent cell (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

CLas movement between phloem cells TEM cross-section images of HLB-infected sweet orange seed coats. A to C, Elongated CLas bacteria passing through the phloem pores. Arrows point to the crossing bacteria. D to F, Movement of the round form of the bacteria between cells. Arrows point to the bacteria changing between the elongated and circular forms.

The round forms of CLas, reaching a diameter of up to 1 μm, were bigger than the diameter of the open pores and, therefore, could not move cell-to-cell while in this form. However, the bacterium had the ability to change its form (Fig. 5D). When a circular bacterium reached the proximity of the phloem pores, sometimes it changed from a circular to an elongated form (Fig. 5E). The elongated part of the bacterium was then able to enter the pores (Fig. 5F).

CLas Bacteria Adhere to Plasma Membrane at the Sieve Plate

The targeting and cell-to-cell movement described here should require some active aspect for CLas movement to target the pores at the right orientation and to enable the translocation. This could be either a bacterial or a host activity, or both. We were therefore looking for a possible cellular mechanism that would enable this. We could detect CLas adhesion to the plasma membrane of the plant cells next to the pores (Fig. 6). CLas binding to the host plasma membrane took place mainly around the phloem pores, and less so at other areas of the cell periphery (outside the sieve plate; Fig. 6A). In some cases, a filamentous-looking link that connected some bacteria with the plasma membrane was seen (Fig. 6, B and C). The identity of this structure and whether it is of bacterial or plant origin is unknown. In other cases, we could detect a clear anchor that connected the bacteria to the plasma membrane (Fig. 6, D–F). These adhesion sites were observed in all the sink tissues we examined (flush, roots, and seed coats) and may represent a general mechanism for phloem pore targeting in citrus.

Figure 6.

CLas adhesion to host plasma membrane observed in TEM cross-section images of HLB-infected Duncan grapefruit (A, B, and F) and sweet orange (C–E) seed coats (A and B), flush (C and D), and roots (E and F). A to C, Attachment of CLas bacteria to the host cell membrane adjacent to the phloem pores through an unknown filamentous material (arrows). D to F, Attachment of CLas bacteria to the host cell membrane adjacent to the phloem pores through an anchor-like link (arrows).

DISCUSSION

The phloem, a major pathway for long distance systemic movement in plants, is involved in the trafficking of photoassimilates, small signaling molecules, and larger macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. The phloem also provides the highway for virus systemic spread in the plant. However, little is yet known about systemic movement inside the phloem, and even less is known about the systemic movement of bacteria. In this work, we documented the passage of the Gram-negative phloem-limited CLas bacteria between phloem sieve-element cells and some of the responses that occur in the phloem pores after bacterial infection of the plants.

CLas infection is known to induce a reorganization of the citrus phloem. This reorganization includes the swelling of the middle lamina, callose deposition, P-protein accumulation, and phloem hyperplasia (Etxeberria et al., 2009; Achor et al., 2010; Folimonova and Achor, 2010; Deng et al., 2019). Here, we investigated different citrus sink tissues to gain further knowledge about the specific cellular reactions that are taking place in the sieve element. TEM images revealed that the responses varied dramatically between different tissues. We observed an increase in the callose levels in the flush, but not in roots or seed coats. Increased callose synthesis and deposition is a general response to plant pathogens (De Storme and Geelen, 2014; Ellinger and Voigt, 2014). It is hypothesized that its role is to isolate the damaged sieve elements and to confine the invading pathogen. However, too much callose may be a “double-edged sword,” and its overproduction may be responsible for the mass-flow impairment and blockage of photoassimilates that were described for HLB. Koh et al. (2012) also showed that the phloem sieve pores’ apertures were reduced by callose, and that photoassimilate export was delayed in CLas-infected plants. They suggested that the massive callose occlusion seen in sieve pores in previous publications might have been a tissue preparation artifact and did not represent the actual in vivo levels (Koh et al., 2012). Here we show that in the flush tissue there is a basal level of callose in healthy controls (that could result in part from tissue preparation), but also that the pore openings are significantly reduced by callose accumulation in the infected plants. When we examined other tissues (such as roots and seed coats) using the same fixation techniques, we found little or no callose at all. This indicates that wound-induced callose resulting from TEM techniques probably only represents a minor part of the plugs. Gene expression analysis of lateral veins from infected grapefruit leaves showed that CalS2, CalS5, and CalS10 were not expressed in the veins, indicating these are not responsible for phloem callose synthesis in grapefruit in response to CLas. CalS3, CalS7, CalS8, CalS9, CalS11, and CalS12 were expressed in the lateral veins. CalS3, CalS7, CalS8, and CalS12 are known to be involved in plasmodesmata/sieve pore callose formation and bacterial infection (Ellinger and Voigt, 2014; Cui and Lee, 2016). CalS9 and CalS11 are known to be mainly involved in callose biosynthesis during pollen development and cell division, but may play an unknown role in the phloem HLB response as well. In both this study and a previous study (Granato et al., 2019), CLas seems to cause a very moderate upregulation of many CalS genes rather than the strong upregulation of a single family member. This may indicate that callose synthesis is regulated at more than the gene-expression level. During abiotic stresses, stress-induced P-protein pore sealing is an almost instant response and callose synthesis rapidly occurs within minutes after abiotic stimulation (Furch et al., 2007; Zavaliev et al., 2011). This rapid response suggests a regulation mechanism at the protein level or the relocalization of P-proteins and CalS complexes which are already present in the sieve elements (Zavaliev et al., 2011). It is possible that an abiotic stress, in addition to the biotic one, is involved in the HLB-related occlusion. Overall, our results support a scenario in which disease symptoms in the flush result from “overproduction” of the occlusion mechanism.

Whereas callose plugging was the main response observed in the young leaves, in the root pores there was very little callose plugging. In the pores, we observed the appearance of an extracellular dark material between the plasma membrane and cell walls. In previous transcriptomic analyses that compared the shoots and roots, it was shown that there are dramatic differences in the symptoms and the transcriptional responses between citrus stems and roots to CLas infection (Aritua et al., 2013; Zhong et al., 2015). They also showed that CalS7 was downregulated in CLas-infected roots (Zhong et al., 2015). Here, we measured the response of CalS7 and PP2 genes to HLB infection in both the shoots and the roots. We found that CLas infection caused a dramatic 100-fold reduction in the expression of phloem-specific CalS7 in the roots, whereas in the shoot, CalS7 was upregulated in the presence of CLas. These results indicate there is a potential mechanism to avoid massive plugging of the root cells, or that a different unknown mechanism (that may be related to the dark deposits we observed) could be taking place. Johnson et al. (2014) showed that CLas accumulation caused severe dieback in the roots. Our results here may be related to cell death.

The seed coats were found to exist at the extreme opposite end of the phloem occlusion gradient. In these tissues, there was no clear sealing of the sieve pores, by either callose or P-protein accumulation. In some cells, sieve pores remained open with no callose at all. In others, callose was present, but only at levels similar to that in healthy controls, without further occlusion. Because there is no direct vascular connection between the seed coat and the developing embryo or endosperm, the area of phloem we studied in the seed coat is probably a trap with no outlet for CLas. As reported in Hilf et al. (2013), CLas multiplied and accumulated in these cells to high numbers, completely filling up the cells, supporting the assumption that sieve pores closure is a plant defense response that limits bacteria spread. Moreover, in this tissue, we could also detect CLas in nucleated cells, and their very high number suggest they are replicating in these cells as well. Phytoplasmas have been detected in phloem parenchyma cells close to the sieve elements (Siller et al., 1987). The identity of these CLas-containing nucleated cells (whether they are developing sieve elements, companion cells, or phloem parenchyma, all of which would have nuclei) and the mechanistic understanding of the bacterial movement into these cells are both still unknown.

Overall, in our study, phloem plugging seemed to restrict CLas levels: There was almost no bacterial accumulation in the tissues where a strong callose production and plugging were observed, whereas bacteria accumulated to high numbers in the areas with little callose plugging. This may reflect differences in plant responses to keep the balance between the need to defend against CLas and the need to maintain plant growth and reproduction. The plant may plug and sacrifice new flush to block the bacteria, but may be more careful with extensive plugging in the roots, which would reduce water and nutrient acquisition. The same could be suggested of the seed coats, because plugging the phloem there would put the developing seed embryo at risk. CLas is not seed-transmittable and does not seem to enter the endosperm and embryo (Tatineni et al., 2008; Hartung et al., 2010; Hilf et al., 2013). The high accumulation of CLas in the seed coats provided a unique opportunity to look at the cell-to-cell movement of CLas. In the nonplugged seed coat phloem, CLas seems to move rather easily between cells. The sieve plate pores that do not contain any callose fit perfectly with the width of the elongated form of the CLas cells. In this conformation, CLas appears to pass through the pores with little or no interference as long as it reaches the pores in the correct orientation (perpendicularly to the membrane). In our images, CLas reached the pores at this exact orientation most of the time, suggesting that the bacterium is using a mechanism for targeting the pores in this orientation. Unlike the elongated form, the circular form of CLas was too large to pass between cells even in the nonplugged seed coats sieve pores, but, as we show here, the bacterial morphological plasticity allows it to change to the narrow form to move.

We further show that CLas cells adhere to the plasma membrane exclusively at the sieve plate, adjacent to the sieve pores. Attachment sites were also described for phytoplasmas (Buxa et al., 2015; Musetti et al., 2016). Plasma membrane attachment next to the pores may provide the necessary targeting mechanism for CLas to reach the pores. Recent studies on plant viruses showed that attachment to plasma membrane proteins serves to target viruses to the plasmodesmata (Raffaele et al., 2009; Levy et al., 2015). It is possible that a similar targeting mechanism is taking place in the sieve pores. The membrane attachment may provide the necessary help to carry the bacteria to the pore in the right orientation, and may also provide a driving force, in addition to the phloem flow, to enable the CLas bacteria to squeeze and pass through the plugged sieve pores. Membrane surface proteins carrying an adhesion motif were described for Onion (Allium cepa) yellows phytoplasmas and Spiroplasma citri (Neriya et al., 2014), but there is no known adhesion protein for CLas that has an additional outer membrane which is not present in phytoplasmas and spiroplasmas.

CONCLUSION

Our results show that CLas triggers different mechanisms that affect the structure of the phloem sieve elements at different sink tissues of trees, and that these mechanisms can limit the accumulation of the bacterium. Our study supports the hypothesis that foliar symptoms result from plant responses rather than the degree of CLas accumulation or activity, because even in the symptomatic flush tissue we could hardly find any CLas cells. We also show that CLas adheres to the plasma membrane at the sieve plate pore, and this mechanism may guide the bacterial cells to pass through the pores, with the help of CLas’ pleomorphic nature. Our results provide visualization of intercellular movement by Gram-negative bacteria, and indicate that important crosstalk is taking place between CLas and the plant at the cellular level, which results in changes to both the bacteria and the host plant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Young Leaf Flush

HLB-infected Madam Vinous sweet orange (Citrus sinensis ‘Osbeck’) and Duncan grapefruit (Citrus paradisi ‘Macompare’ with ‘Duncan’) were generated as described in Folimonova and Achor (2010). In short, HLB inoculum was collected from symptomatic field trees located in a grove in Highlands County, Florida and was further propagated by grafting into Madam Vinous sweet orange. Each variety was graft-inoculated with three pieces of budwood from PCR-positive HLB source trees and propagated in the greenhouse. Two weeks after grafting, the plants were trimmed back to stimulate the development of new growth. Visual observation of symptoms along with PCR assays were performed.

Seed Coats

Developing immature seeds (half to two-thirds mature size) from field-infected Valencia sweet orange and Duncan grapefruit showing visible symptoms of infection (small, lopsided growth) were collected in early summer when the sweet orange fruits were 3.7 cm in diameter and grapefruit fruit were only ∼6 cm in diameter, from the Teaching Grove at the Citrus Research and Education Center (University of Florida). Healthy Duncan grapefruit seeds of the same age were collected from plants grown in citrus under protective screen. Phloem tissue was imaged from the chalazal end of these seeds, as described in Hilf et al. (2013).

Roots

Fibrous root tissue was taken from Duncan grapefruit and Madam Vinous sweet orangeseedlings, and from Valencia grown on Volk (Citrus volkamericana) rootstock. Plants were graft-inoculated as above and green-house–propagated 5–7 months before sample collection.

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy analysis was performed as described in Folimonova and Achor (2010), using a standard fixation procedure as follows. Samples were fixed with 3% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m of potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 for 4 h at room temperature, washed in phosphate buffer, then postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide (w/v) in the same buffer for 4 h at room temperature. The samples were further washed in the phosphate buffer, dehydrated in a 10% acetone (v/v) series (10 min per step), and infiltrated and embedded in Spurr’s resin over 3 d. Sections (100-nm) were mounted on 200-mesh formvar-coated copper grids, stained with 2% aq uranyl acetate (w/v) and Reynolds lead citrate, and examined with a Morgagni 268 transmission electron microscope (FEI).

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR

To determine differences in CalS7 and PP2 genes in citrus (Citrus macrophylla) tissues, we utilized reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to quantify the relative abundance of CalS7 (GeneID: 102612996) and PP2 (GeneID: 102625021) transcripts in different tissues between noninfected and HLB-infected citrus plants (three plants each). Flush (young leaves), bark (internode between flush and first fully expanded leaves), midrib of mature leaves (from two to four fully expanded leaves from flush), and roots (young fibrous roots) tissues were excised from three plants each of HLB-infected and noninfected plants for RNA extractions. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Life Technologies) followed by DNase I (Life Technologies) treatment and LiCl precipitation to purge DNA contaminants. The SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen; https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/18080051#/18080051) was used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using 250 ng of total RNA extract per sample, alongside 0.2 μm of gene-specific primers (CalS7, TGGGCAGACGAAGATTTGGTA/GACATGAAGCCAAGGAATAGGA; PP2, CGGCATACGGATGGGAAGTAC/TCGCCAACAGGGATCTCTATC; ActB, GTTGCCATTGGTTGGTATTTGATAC/CGTCGACTGCCATTCCAGAT; GAPDH, TGGCGACCAAAGGCTACTC/TTGCCGCACCAGTTGATG reference genes; Harper et al., 2014) in 20-μL reactions. The TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used for qPCRs as follows. Each reaction (10-μL volumes) was set up in triplicates consisting of: 2 μL of cDNA template, 0.4 μM of forward and reverse primers, and 50 nm of gene-specific 6-FAM/BHQ-1 labeled TaqMan probe (CalS7, 6-FAM-TCAGCTCATGTTCAGGATTCTCAAAGCA-BHQ1; PP2, 6-FAM-CAGTGAGCCTAAGACTCCTCTTACCA-BHQ1; ActB, 6-FAM-TGGTCGATGATTTGTCCGATTCACA-BHQ1; and GAPDH, 6-FAM-TGCTAGCCACCGTGACCTCAGG-BHQ1). Cycling conditions for qPCR were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Raw qPCR data were analyzed with the program LinRegPCR v2013.0 (http://linregpcr.nl) to correct for differences in reaction efficiency. The Ct values were averaged for each target, then used to calculate the relative quantification (RQ) values by the method described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001) against the geometric mean of the Ct values of GAPDH/ActB reference genes. RQ values were Log10-transformed before multiple Student’s t tests (Holm–Sidak method, α = 0.05) to compare tissue means with the software GraphPad (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/).

To determine gene expression in lateral veins of grapefruit, leaf samples (three plants each) were collected from healthy and infected grapefruit trees. RNA was extracted from 100 mg of lateral leaf vein tissue with the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), cDNA was prepared from the RNA. RT-qPCR was performed with the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Each cDNA sample was diluted to a standardized concentration of 40 ng/μL. Separate qPCR reaction mixtures for each sample contained 160 ng of cDNA and primers for each gene at a concentration of 10 mM, with a total volume of 10 μL.

Thermocycling was performed using a model no. 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with the following settings: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 35 s and 60°C for 30 s. For CalS genes, we employed the primer sequences that were designed by Granato et al. (2019), based on the C. sinensis genome that contains homologs for the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) CalS2, CalS3, CalS5, CalS7, CalS8, CalS9, CalS10, CalS11, and CalS12 genes. For citrus PP2 gene expression, primers were designed to target citrus homologous regions of Arabidopsis PP2-B10 and PP2-B15 genes (Table 1). Gene expression was compared to citrus ActB reference gene, and analysis was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Table 1. Primers sequences designed to target homologous regions of citrus PP2 genes that exhibit elevated expression during CLas infection.

| Citrus Gene Target | Arabidopsis Homolog | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Orange1.1g024966m | P-protein 2-B10 | F: GAAGGAAGCGATAATGGG |

| Orange1.1g024822m | R: TTGAAGAACTCGCCCATCTC | |

| Orange1.1g041394m | P-protein 2-B10 | F: AAATGTTACATGGTTGGGGC |

| Orange1.1g045187m | R: TTCTTGTCTCTATCCTTGCG | |

| Orange1.1g042480m | ||

| Orange1.1g039003m | P-protein 2-B15 | F: TCTCATAGACGGCGGTAGAA |

| R: GGAAGGTTTCCAGCTCCAATA |

Image and Statistical Analyses

Pores openings were measured using the software ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Statistical analysis was performed using the software JMP 14 (https://www.jmp.com/en_us/home.html). Means were compared using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test and Student’s t test.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: PP2s: XM_006489708 (orange1.1g024966m), XM_006489711 (orange1.1g024822m), XM_006420794 (orange1.1g041394m), XM_025092274 (orange1.1g045187m), XM_006420801 (orange1.1g042480m), and XM_006481644 (orange1.1g039003m). CalSs: XM_025101248 (orange1.1g001004m; CalS2), XM_006492601 (orange1.1g000171m; CalS3), XM_025101748 (orange1.1g045737m; CalS5), XM_006484824 (orange1.1g000389m; CalS7), XM_006477876 (orange1.1g000165m; CalS8), XM_006492604 (orange1.1g000179m; CalsS9), XM_025098709 (orange1.1g000180m, CalS10), XM_006467737 (orange1.1g000258m; CalS11), and XM_025092689 (orange1.1g000259m; CalS12).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. TEM images of completely plugged phloem cells from HLB-infected sweet orange flush and grapefruit roots.

Supplemental Figure S2. TEM images of grapefruit seed coats.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Vladimir Orbovic, Dr. Arnold Scumann, and Laura Waldo (University of Florida) for providing us healthy Duncan Grapefruit seeds, and Dr. Robert Turgeon (Cornell University) for helpful suggestions during the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Early Career Seed Grant (No. 00127818 to A.L.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Achor DS, Etxeberria E, Wang N, Folimonova SY, Chung KR, Albrigo LB (2010) Sequence of anatomical symptom observations in citrus affected with Huanglongbing disease. Plant Pathol J 9: 56–64 [Google Scholar]

- Aloni R, Raviv A, Peterson CA (1991) The role of auxin in the removal of dormancy callose and resumption of phloem activity in Vitis vinifera. Canadian J Botany-Revue Canadienne De Botanique 69: 1825–1832 [Google Scholar]

- Aritua V, Achor D, Gmitter FG, Albrigo G, Wang N (2013) Transcriptional and microscopic analyses of citrus stem and root responses to Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus infection. PLoS One 8: e73742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt DHP, Kölling K, Graf A, Pike M, Calder G, Findlay K, Zeeman SC, Smith AM (2011) Callose synthase GSL7 is necessary for normal phloem transport and inflorescence growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 155: 328–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke HD, Sjolund RD (1990) Sieve Elements. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York [Google Scholar]

- Bove JM. (2006) Huanglongbing: A destructive, newly-emerging, century-old disease of citrus. J Plant Pathol 88: 7–37 [Google Scholar]

- Buxa SV, Degola F, Polizzotto R, De Marco F, Loschi A, Kogel K-H, di Toppi LS, van Bel AJE, Musetti R (2015) Phytoplasma infection in tomato is associated with re-organization of plasma membrane, ER stacks, and actin filaments in sieve elements. Front Plant Sci 6: 650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Lee J-Y (2016) Arabidopsis callose synthases CalS1/8 regulate plasmodesmal permeability during stress. Nat Plants 2: 16034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Storme N, Geelen D (2014) Callose homeostasis at plasmodesmata: Molecular regulators and developmental relevance. Front Plant Sci 5: 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Achor D, Exteberria E, Yu Q, Du D, Stanton D, Liang G, Gmitter FG Jr. (2019) Phloem regeneration is a mechanism for Huanglongbing-tolerance of “Bearss” Lemon and “LB8-9” Sugar Belle® Mandarin. Front Plant Sci 10: 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinger D, Voigt CA (2014) Callose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis with a focus on pathogen response: What we have learned within the last decade. Ann Bot 114: 1349–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria E, Gonzalez P, Achor D, Albrigo G (2009) Anatomical distribution of abnormally high levels of starch in HLB-affected Valencia orange trees. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 74: 76–83 [Google Scholar]

- Folimonova SY, Achor DS (2010) Early events of citrus greening (Huanglongbing) disease development at the ultrastructural level. Phytopathology 100: 949–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furch ACU, Hafke JB, Schulz A, van Bel AJ (2007) Ca2+-mediated remote control of reversible sieve tube occlusion in Vicia faba. J Exp Bot 58: 2827–2838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato LM, Galdeano DM, D’Alessandre NDR, Breton MC, Machado MA (2019) Callose synthase family genes plays an important role in the Citrus defense response to Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus. Eur J Plant Pathol 155: 25–38 [Google Scholar]

- Harper SJ, Cowell SJ, Robertson CJ, Dawson WO (2014) Differential tropism in roots and shoots infected by Citrus tristeza virus. Virology 460–461: 91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung JS, Halbert SE, Pelz-Stelinski K, Brlansky RH, Chen C, Gmitter FG (2010) Lack of evidence for transmission of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ through citrus seed taken from affected fruit. Plant Dis 94: 1200–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilf ME, Sims KR, Folimonova SY, Achor DS (2013) Visualization of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ cells in the vascular bundle of citrus seed coats with fluorescence in situ hybridization and transmission electron microscopy. Phytopathology 103: 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis CA, Tepper HB (1971) Auxin transport within intact dormant and active white ash shoots. Plant Physiol 48: 146–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EG, Wu J, Bright DB, Graham JH (2014) Association of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ root infection, but not phloem plugging with root loss on Huanglongbing-affected trees prior to appearance of foliar symptoms. Plant Pathol 63: 290–298 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-S, Sagaram US, Burns JK, Li J-L, Wang N (2009) Response of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) to ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ infection: Microscopy and microarray analyses. Phytopathology 99: 50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch M, Froelich DR, Pickard WF, Peters WS (2014) SEORious business: Structural proteins in sieve tubes and their involvement in sieve element occlusion. J Exp Bot 65: 1879–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch M, Peters WS, Ehlers K, van Bel AJE (2001) Reversible calcium-regulated stopcocks in legume sieve tubes. Plant Cell 13: 1221–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch M, van Bel AJE (1998) Sieve tubes in action. Plant Cell 10: 35–50 [Google Scholar]

- Koh E-J, Zhou L, Williams DS, Park J, Ding N, Duan Y-P, Kang B-H (2012) Callose deposition in the phloem plasmodesmata and inhibition of phloem transport in citrus leaves infected with “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus.”. Protoplasma 249: 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Zheng JY, Lazarowitz SG (2015) Synaptotagmin SYTA forms ER-plasma membrane junctions that are recruited to plasmodesmata for plant virus movement. Curr Biol 25: 2018–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔC(T) method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Song W, Sage TL, DellaPenna D (2006) Tocopherols play a crucial role in low-temperature adaptation and phloem loading in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 2710–2732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNairn RB. (1972) Phloem translocation and heat-induced callose formation in field-grown Gossypium hirsutum L. Plant Physiol 50: 366–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNairn RB, Currier HB (1968) Translocation blockage by sieve plate callose. Planta 82: 369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musetti R, Pagliari L, Buxa SV, Degola F, De Marco F, Loschi A, Kogel K-H, van Bel AJE (2016) Phytoplasmas dictate changes in sieve-element ultrastructure to accommodate their requirements for nutrition, multiplication and translocation. Plant Signal Behav 11: e1138191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neriya Y, Maejima K, Nijo T, Tomomitsu T, Yusa A, Himeno M, Netsu O, Hamamoto H, Oshima K, Namba S (2014) Onion yellow phytoplasma P38 protein plays a role in adhesion to the hosts. FEMS Microbiol Lett 361: 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele S, Bayer E, Lafarge D, Cluzet S, German Retana S, Boubekeur T, Leborgne-Castel N, Carde JP, Lherminier J, Noirot E, et al. (2009) Remorin, a Solanaceae protein resident in membrane rafts and plasmodesmata, impairs potato virus X movement. Plant Cell 21: 1541–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read SM, Northcote DH (1983) Chemical and immunological similarities between the phloem proteins of three genera of the Cucurbitaceae. Planta 158: 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller W, Kuhbandner B, Marwitz R, Petzold H, Seemüller E (1987) Occurrence of mycoplasma-like organisms in parenchyma cells of Cuscuta odorata (Ruiz et Pav.). J Phytopathol 119: 147–159 [Google Scholar]

- Stone BA, Clarke AE (1992) Chemistry and physiology of higher plants (1–3)-beta-glucans In In Chemistry and Biology of (1–3)-Beta Glucans. La Trobe University Press, Victoria, Australia, pp 365–429 [Google Scholar]

- Tatineni S, Sagaram US, Gowda S, Robertson CJ, Dawson WO, Iwanami T, Wang N (2008) In planta distribution of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ as revealed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time PCR. Phytopathology 98: 592–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhou L, Yu X, Stover E, Luo F, Duan Y (2016) Transcriptome profiling of Huanglongbing (HLB) tolerant and susceptible citrus plants reveals the role of basal resistance in HLB tolerance. Front Plant Sci 7: 933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster DB, Currier HH (1965) Callose: Lateral movement of assimilates from phloem. Science 150: 1610–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Hong Z (2011) Unplugging the callose plug from sieve pores. Plant Signal Behav 6: 491–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Wang X, Zhu M, Zhang Z, Hong Z (2011) CalS7 encodes a callose synthase responsible for callose deposition in the phloem. Plant J 65: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaliev R, Ueki S, Epel BL, Citovsky V (2011) Biology of callose (β-1,3-glucan) turnover at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 248: 117–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Cheng CZ, Jiang NH, Jiang B, Zhang YY, Wu B, Hu ML, Zeng JW, Yan HX, Yi GJ, Zhong GY (2015) Comparative transcriptome and iTRAQ proteome analyses of citrus root responses to ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ infection. PLoS One 10: e0126973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]