Reovirus serotype 3 Dearing (T3D) is in clinical trials for cancer therapy. Recently, it was discovered that highly related laboratory strains of T3D exhibit large differences in their abilities to replicate in cancer cells in vitro, which correlates with oncolytic activity in a murine model of melanoma. The current study reveals two mechanisms for the enhanced efficiency of T3DPL in cancer cells. Due to polymorphisms in two viral genes, within the first round of reovirus infection, T3DPL binds to cells more efficiency and more rapidly produces viral RNAs; this increased rate of infection relative to that of the less oncolytic strains gives T3DPL a strong inherent advantage that culminates in higher virus production, more cell death, and higher virus spread.

KEYWORDS: reovirus, T3D, attachment, genetic polymorphisms, μ2, oncolysis, σ1, strain diversity, transcription

ABSTRACT

Reovirus serotype 3 Dearing (T3D) replicates preferentially in transformed cells and is in clinical trials as a cancer therapy. Laboratory strains of T3D, however, exhibit differences in plaque size on cancer cells and differences in oncolytic activity in vivo. This study aimed to determine why the most oncolytic T3D reovirus lab strain, the Patrick Lee laboratory strain (T3DPL), replicates more efficiently in cancer cells than other commonly used laboratory strains, the Kevin Coombs laboratory strain (T3DKC) and Terence Dermody laboratory (T3DTD) strain. In single-step growth curves, T3DPL titers increased at higher rates and produced ∼9-fold higher burst size. Furthermore, the number of reovirus antigen-positive cells increased more rapidly for T3DPL than for T3DTD. In conclusion, the most oncolytic T3DPL possesses replication advantages in a single round of infection. Two specific mechanisms for enhanced infection by T3DPL were identified. First, T3DPL exhibited higher cell attachment, which was attributed to a higher proportion of virus particles with insufficient (≤3) σ1 cell attachment proteins. Second, T3DPL transcribed RNA at rates superior to those of the less oncolytic T3D strains, which is attributed to polymorphisms in M1-encoding μ2 protein, as confirmed in an in vitro transcription assay, and which thus demonstrates that T3DPL has an inherent transcription advantage that is cell type independent. Accordingly, T3DPL established rapid onset of viral RNA and protein synthesis, leading to more rapid kinetics of progeny virus production, larger virus burst size, and higher levels of cell death. Together, these results emphasize the importance of paying close attention to genomic divergence between virus laboratory strains and, mechanistically, reveal the importance of the rapid onset of infection for reovirus oncolysis.

IMPORTANCE Reovirus serotype 3 Dearing (T3D) is in clinical trials for cancer therapy. Recently, it was discovered that highly related laboratory strains of T3D exhibit large differences in their abilities to replicate in cancer cells in vitro, which correlates with oncolytic activity in a murine model of melanoma. The current study reveals two mechanisms for the enhanced efficiency of T3DPL in cancer cells. Due to polymorphisms in two viral genes, within the first round of reovirus infection, T3DPL binds to cells more efficiency and more rapidly produces viral RNAs; this increased rate of infection relative to that of the less oncolytic strains gives T3DPL a strong inherent advantage that culminates in higher virus production, more cell death, and higher virus spread.

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian orthoreovirus (MRV; reovirus) has served as an important model system since being isolated by Albert Sabin in 1959. The three serotypes of reovirus are each represented by a prototypic strain: type 1 Lang (T1L), type 2 Jones (T2J), and type 3 Dearing (T3D). Although naturally nonpathogenic in humans, reovirus can cause myocarditis and central nervous system infection in immunocompromised mice in a serotype-specific manner (1–4), thus providing a safe model system to study the effects of virus and innate signaling in vivo. Numerous studies have also used reovirus serotype comparisons in vitro to understand fundamental aspects of viruses, such as how proteinaceous capsids assemble and disassemble. Most recently, interest in reovirus has grown owing to discovery that serotype 3 reovirus (T3D) possesses potent oncolytic properties (5). Specifically, T3D was found to replicate preferentially in tumors and cancer cells over nontransformed cells and healthy tissues. Accordingly, T3D is currently in phase III clinical trials for cancer therapy and is the subject of research worldwide in laboratories interested in virus oncolysis.

Even within the T3D prototypical serotype 3 reovirus, there is significant divergence between laboratory strains (6). Importantly, the laboratory strains of T3D exhibited distinct oncolytic potential in vivo, with the Patrick Lee laboratory strain (T3DPL; identical at the amino acid level to the T3DReolysin strain being tested in clinical trials) being most effective at tumor regression. The study also found that T3D laboratory strains caused distinct plaque morphology, with large-plaque formation correlating with in vivo oncolytic potency. These findings not only raised the importance of using shared virus stocks for oncolytic studies worldwide but also afforded a new opportunity to understand features of reovirus that contribute to good oncolysis. Since differences in plaque size can arise from differential efficiency of many stages of virus infection, replication, and/or dissemination, we sought to understand which stages of virus replication contribute to the large-plaque phenotype of the most oncolytic T3D strain.

The reovirus genome is packaged within the viral core and is composed of 10 double-stranaded RNA (dsRNA) segments: 4 small (S1, S2, S3, and S4), 3 medium (M1, M2, and M3), and 3 large (L1, L2, and L3) (7). The 10 genome segments encode 12 proteins: 8 structural (σ1, σ2, σ3, μ1, μ2, λ1, λ2, and λ3) and 4 nonstructural (σ1s, σNS, μNS, and μNSC). Note that the naming of reovirus dsRNA segments and proteins was based on electrophoretic molecular weights and therefore can get confusing; for example, L1 (slowest-migrating L genome segment) encodes λ3 (fastest-migrating large reovirus protein). Using reassortment analysis and reverse genetics, the polymorphisms associated with the large-plaque phenotype of T3DPL relative to that of the less oncolytic but commonly used Terence Dermody laboratory strain (T3DTD) were mapped to the S4, M1, and L3 genome segments. The σ3 protein encoded by the S4 gene comprises the outermost virus capsid and plays a major role in maintaining virus stability in the environment (8–10). Aside from its structural role, σ3 binds dsRNA during virus infection functions to overcome PKR signaling and to maintain viral protein translation (11, 12). The μ2 encoded by the M1 gene also provides at least two functions during reovirus replication. Within reovirus core particles, μ2 is a λ3 polymerase cofactor, supplying nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) activity and supporting temperature-dependent core transcriptase activity. During reovirus replication, μ2 is also a determinant of virus factory morphology, bridging tubulin to μNS, which subsequently recruits other viral proteins and RNAs (13–18). The λ1 protein encoded by the L3 gene is a major component of the viral core inner capsid and has dsRNA binding, NTPase, and RNA helicase activity (18–21).

In this study, a comprehensive analysis of T3D laboratory strains revealed that the most oncolytic strain (T3DPL) has much faster kinetics of infection than the less oncolytic strains (T3DTD and the Kevin Coombs laboratory strain [T3DKC]) in a single round of replication. The more rapid infection leads to more viral RNA, protein, and progeny production and, ultimately, to faster cell death and reovirus dissemination. These findings point to the importance of inherent differences in virus replication proficiency and intracellular permissively bestowed by single amino acid polymorphisms. Two specific mechanisms for rapid infection were identified: first, T3DPL had superior binding to tumor cells, and, second, T3DPL core particles had faster kinetics of transcription. Genetic assortment showed that the polymorphic M1-encoded μ2 was responsible for increased core transcription levels of T3DPL, linking μ2 as an important determinant of transcription rate and timely infection.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [53].)

RESULTS

T3DPL replicates more rapidly and to higher burst size in a single round of infection.

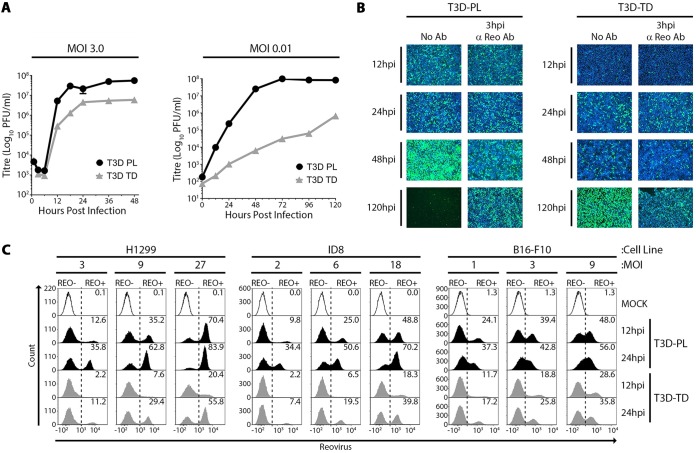

The T3DPL reovirus strain exhibited oncolytic activities superior to those of the T3DTD strain in a murine melanoma model and also caused larger plaques than a variety of laboratory T3D strains including T3DTD (see the accompanying manuscript [6]). The larger plaques produced by T3DPL could stem from more rapid rates of virus replication, increased burst size, enhanced cell lysis and virus release, or increased cell-to-cell spread. To determine if T3DPL replicates more rapidly and/or to higher burst size than T3DTD in a single round of infection, single-step virus growth analyses were performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 (Fig. 1A, left). L929 cells were exposed to T3DPL and T3DTD at 4°C for 1 h to synchronize infection, washed to remove unbound viruses, and then incubated at 37°C for various time periods. Reovirus titers at onset of infection were similar between T3DPL and T3DTD, indicating equal input infectious virions as calculated. Following entry, reovirions uncoat to cores and become noninfectious, leading to reduced titers at 3 and 6 h postinfection (hpi) for both T3DPL and T3DTD. Between 8 and 12 hpi, ∼1,000-fold new infectious progeny was produced per input of T3DPL. In contrast, titers increased by only ∼50-fold for T3DTD. T3DPL reached maximum saturation titers at 18 hpi, while T3DTD titers were saturated at 24 hpi. Furthermore, saturation titers for T3DPL were ∼9-fold higher than those for T3DTD. The one-step growth curves therefore indicated that new progeny production for T3DPL occurs faster and produces higher virus burst size than that of T3DTD. Importantly, these findings suggest that oncolytic potential correlates with proficiency of virus replication in a single round of replication.

FIG 1.

T3DPL replicates more rapidly and to higher burst size in a single round of infection. (A) L929 cells were infected with T3DPL or T3DTD at an MOI of 3 (left) or 0.01 (right) and incubated at 37°C. At each time point, total cell lysates were harvested, and virus titers were determined in duplicate on L929 cells. Data represents mean ± standard deviations (n = 3). (B) L929 cells were infected with T3DPL or T3DTD (MOI of 1) and incubated at 37°C. Polyclonal reovirus antibody was added directly to the well medium at 3 hpi (3 hpi anti-Reo Ab). Reovirus=infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using polyclonal anti-reovirus antibodies (green) and HOECHST staining of cell nuclei (blue). (C) H1299, ID8, and B16-F10 cancer cell lines were mock infected or infected with T3DPL or T3DTD at the indicated MOI (based on titers established on L929 cells) and incubated at 37°C for 12 or 24 h. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with reovirus-specific primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody and to flow cytometric analysis. Gates were set based on mock-infected cells.

When multistep virus growth curves were performed at an MOI of 0.01, the cumulative advantage of improved replication over several rounds of infection was striking: T3DPL accumulated ∼4,000-fold higher virus titers than T3DTD by 48 hpi (Fig. 1A, right).

As a complementary approach to monitor the rate of reovirus initial infection versus cell-cell spread, we used immunofluorescence staining of reovirus antigen-positive L929 cells (Fig. 1B). In order to decipher the extent of cell-cell spread versus initially infected cells, staining was compared in the absence or presence of reovirus neutralizing antibodies added at 3 hpi to prevent cell-cell spread. Cells became positive for T3DPL staining more rapidly than for T3DTD (e.g., compare viruses at 12 hpi) and equalized at ∼24 hpi. By 48 hpi, T3DPL very effectively spread to neighboring cells (i.e., compare staining 48 hpi without antibody [Ab] to that with anti-reovirus Ab), while limited cell-cell spread was observed for T3DTD. By 120 hpi, very few cells remained alive following T3DPL infection, as indicated by a lack of Hoechst nuclear staining. In comparison, T3DTD successfully underwent cell-cell spread by 120 hpi, but cells remained relatively intact. The 48-hpi time point represents only two rounds of reovirus replication yet demonstrates the strong compounding difference between T3D laboratory strains with respect to replication and spread on tumorigenic cells (i.e., in vitro oncolysis).

To determine if faster kinetics of establishing infection was an inherent property of T3DPL, kinetics of infection were compared for T3DPL and T3DTD in different cancer cell lines. Human lung carcinoma cells (H1299), mouse ovarian carcinoma cells (ID8), and the murine melanoma cells previously used to compare oncolytic potency of T3DPL and T3DTD in vivo (B16-F10) were exposed to the two T3D strains at various MOIs. Note that these three cell lines show differential infectivities to reovirus relative to each other, and, hence, MOIs for a given cell line were chosen to give approximately 10%, 30%, and 60% infected cells. At 12 and 24 hpi, flow cytometric analysis was performed to quantify the proportion of reovirus protein-expressing cells (Fig. 1C). In all three cancer cell lines, T3DTD infection was delayed, giving the same percentages of infected cells at 24 hpi as already achieved by T3DPL at 12 hpi. Together, the data suggested that T3DPL inherently replicates more rapidly and to higher burst size in a single round of infection.

T3DPL shows minor enhancement in cell attachment.

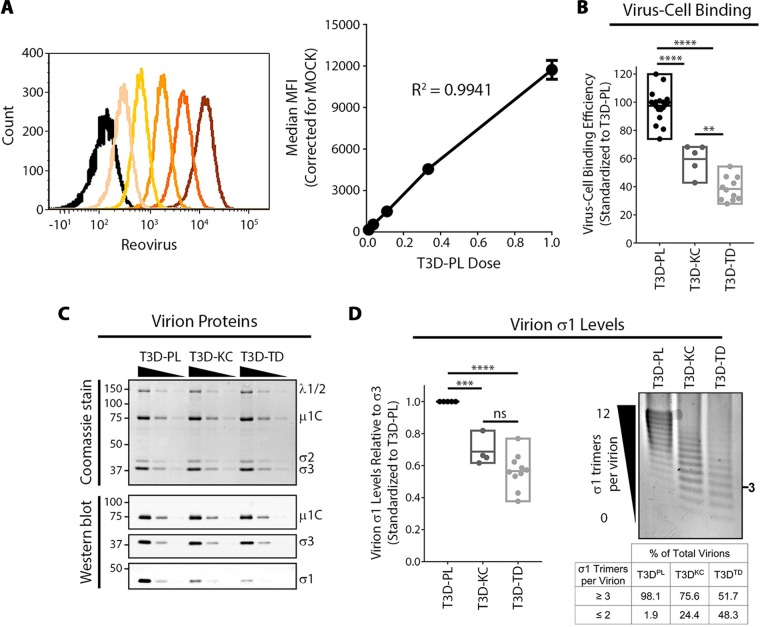

Increased virus replication shown observed in Fig. 1 could result from higher efficiency of virus entry or postentry steps of virus replication and assembly. The first and commonly studied step of virus infection is attachment to cells. We therefore compared cell attachment efficiencies between CsCl gradient-purified T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD strains, with T3DKC being a third laboratory strain of T3D that causes smaller plaques than T3DPL (6). L929 cells were exposed to equivalent particle numbers of each laboratory strain at 4°C for 1 h to permit virus binding without entry and then washed extensively. Flow cytometric analysis was used to measure bound virions per cell; in this approach the mean fluorescence intensity has a linear relationship with the number of cell-bound virions, enabling standard curves to be generated with serial dilutions of T3DPL and used to extrapolate relative numbers of bound particles for T3DKC and T3DTD strains (Fig. 2A). Reproducibly, T3DKC and T3DTD bound cells at 60% and 40% efficiencies relative to cell binding by T3DPL (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

T3DPL exhibits minor enhancement in cell attachment. (A) Using nonenzymatically detached L929 cells in suspension, T3DPL dilutions were bound at 4°C, and following extensive washing to remove unbound reovirus, cell-bound reovirus was stained using polyclonal reovirus antibodies. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified using flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto). Black histogram, mock infection; dark orange, most concentrated; light orange, least concentrated. Linear regression analysis of MFI was determined from serial dilutions and corrected for mock-infected background. (B) Corrected for similar particle numbers using Coomassie staining, cell binding of T3DKC and T3DTD was performed as described for panel A (left) and standardized to T3DPL using curve from panel A (right; n ≥ 5). One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was performed **, P < 0.0021; ****, P < 0.0001. (C) CsCl-purified reovirus preparations were separated using SDS-PAGE. Total protein was stained using Imperial Coomassie dye while specific reovirus proteins were identified using Western blot analysis with protein-specific antibodies. (D) Agarose gel separation and Imperial Coomassie dye staining of virions based on the number of σ1 trimers per virion. The table indicates percentage of virions with specific number of σ1 timers/virion calculated using densitometric band quantification obtained with an ImageQuantTL 1D gel analysis add-on (n ≥ 4). One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was performed ***, P < 0.0001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, P > 0.05.

For reovirus, cell binding is mediated by the trimeric σ1 protein that extends from channels generated by pentameric λ2 proteins at vertices of reovirus particles. Previous studies showed that reovirus particles can have 0 to 12 σ1 trimers, and that 3 or more σ1 trimers per virion are necessary and sufficient for virion binding to cells (22, 23). We therefore queried the levels of σ1 on T3D laboratory strains. First, CsCl gradient-purified T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD virus particles were subjected to denaturing gel electrophoresis, and proteins were visualized by Imperial total protein staining (Fig. 2C, top) and Western blot analysis using reovirus protein-specific antibodies (Fig. 2C, bottom). The ratio of capsid proteins λ1/2, μ1C, σ2, and σ3 were similar between T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD. However, for equivalent capsid protein (σ3), T3DKC and T3DTD had lower average levels of σ1 than T3DPL. Agarose gel separation of full virions was then applied to quantify the proportion of virions with fewer than three σ1 trimers, which would be incapable of cell binding (Fig. 2D). While 24% and 48% of T3DKC and T3DTD particles (respectively) had fewer than three σ1 trimers per virion, only 2% of T3DPL particles had insufficient σ1 trimers for binding. The proportion of virions with ≥3 σ1 trimers per virion correlated closely to the percentage of cell bound particles shown in Fig. 2B. Together the analysis indicates that oncolytic potency of the most oncolytic laboratory strain T3DPL correlates with enhanced attachment to tumor cells, which in turn can be explained by a higher proportion of virus particles with ≥3 σ1 trimers per virion.

Postentry steps of reovirus replication are strongly enhanced for T3DPL.

Following attachment to cells, reovirus undergoes endocytosis and trafficking to lysosomes where cathepsins L and B mediate virus uncoating (24–28). Specifically, during reovirus uncoating, the outermost σ3 protein is degraded, and μ1C is cleaved to the membrane-destabilizing products δ, μ1N, and φ. The resulting intermediate subviral particle (ISVP) is capable of penetrating membranes and delivering the final reovirus core particle to the cytoplasm (29–34). Cleavage of σ3 and μ1C was monitored by Western blotting analysis at various time points postinfection. Complete cleavage of σ3 was observed by 3 hpi and coincided with initiation of μ1C to δ cleavage (Fig. 3A). The rate of μ1C cleavage to δ was quantified as a percentage of δ to the total of δ plus μ1C standardized to the level of β actin (housekeeping protein). All T3D strains had similar uncoating rates, and almost complete uncoating was attained by 5 hpi. De novo-synthesized μ1 (i.e., precursor to μ1C) and σ3 were observed at 5 hpi in T3DPL but not in T3DKC and T3DTD.

FIG 3.

Postentry steps of reovirus replication are strongly enhanced for T3DPL. (A) T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD (MOIs of 1 to 3) were bound to L929 cell monolayers at 4°C and following washing to remove unbound virions, cells were incubated at 37°C and cell lysates were collected at various time points postinfection. Total proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis with specific antibodies was used to identify reovirus proteins and β actin (loading control) (left). Densitometric band quantification of μ1C and δ and percent virus uncoating (right) were calculated using the following formula; [δ/(μ1C + δ)] ×100 (n = 4 ± standard deviation; MOI of 1, n = 2; MOI of 3, n = 2). Linear regression analysis determined that the slopes are not significantly different. (B to D) L929 cells were exposed to T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD (MOI of 3) at 4°C for 1 h, washed, and incubated at 37°C. At indicated time points, following total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis, reovirus S4 and M2 RNA expression levels relative to the level of the housekeeping gene GAPDH were quantified using RT-qPCR (n = 3 ± standard deviation; ***, P < 0.0001). Linear regression analysis determined that (i) the slope of T3DPL differs from that of T3DKC or T3DTD and (ii) the slope of T3DKC does not differ from that of T3DTD. (C) Total proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis with specific antibodies were used to identify reovirus proteins and β actin (loading control). (D) Adherent and detached cells were collected at 24 hpi and subjected to staining with 7-AAD and annexin V, followed by flow cytometric analysis. PE, phycoerythrin.

After removal of the outer capsid, reovirus cores that enter the cytoplasm become transcriptionally active. Positive-sense mRNAs are transcribed within reovirus cores and released into the cytoplasm for translation by host protein synthesis machinery (35–38). To assess overall accumulation of viral RNA, we used quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR) for S4 and M2 as representative viral RNAs over the course of infection (Fig. 2B). Over 12 hpi, viral transcripts accumulated at a significantly higher rate for T3DPL than T3DKC/T3DTD. Specifically, prior to viral RNA saturation at 8 hpi, T3DPL exhibited 77- and 85-fold higher levels of S4 viral RNA than T3DKC and T3DTD, respectively (Fig. 2B, left). Differences in viral M2 RNA levels were even greater, with T3DPL having 92- and 133-fold higher levels than T3DKC and T3DTD, respectively (Fig. 2B, right). As anticipated, viral protein levels closely reflected virus transcript levels; Western blot analysis with polyclonal anti-reovirus antibody showed substantially higher accumulation of T3DPL viral proteins than of T3DKC and T3DTD proteins at every time point from 6 hpi onward (Fig. 2C). Not surprisingly given the large increase in kinetics and total level of viral RNA and proteins for T3DPL, cell death measured by flow cytometry with annexin V (measures early apoptosis) or 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; measures cell death) was higher for T3DPL than for T3DTD, with, for example, values of ∼85% versus 19% at an MOI of 3 for these strains, respectively (Fig. 2D). The analysis indicates that kinetics of reovirus macromolecule synthesis are drastically faster for T3DPL than for T3DTD, which explains the accelerated replication and larger burst size for T3DPL in the one-step growth curves shown in Fig. 1.

S4, M1, and L3 polymorphisms independently contribute to enhanced viral RNA and protein synthesis by T3DPL.

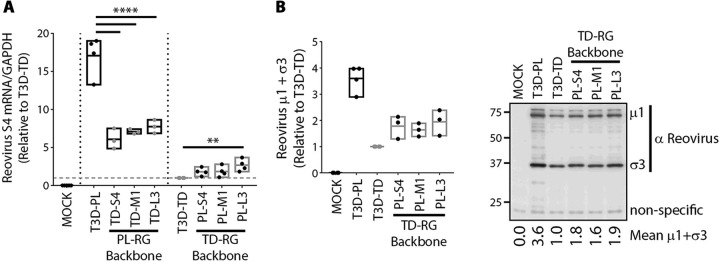

Using reassortment and reverse genetics analysis, M1, S4, and L3 reovirus genes were previously associated with increased plaque size of T3DPL (6). Specifically, monoreassortants that contained one of these genes independently from T3DPL in an otherwise T3DTD background (or vice-versa) caused plaque size that was intermediate between the two T3D strains. Only when all three gene segments were introduced together was plaque size restored to that of the parental virus phenotype. Our current analysis indicated that differences between T3DPL and T3DTD were already apparent in the first round of replication, so we determined if M1, S4, and L3 reovirus genes contributed to differential levels of viral RNA and protein between the T3D strains. RNA and protein analysis were chosen over later steps in virus replication in order to capture the earliest difference between T3D laboratory strains. Quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4A) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B) were repeated for single mono-reassortants at 12 hpi. M1, S4, and L3 genes from T3DPL increased reovirus RNAs when placed in an otherwise TDRG background relative to levels of T3DTD. In the reciprocal mono-reassortment, M1, S4, and L3 genes from T3DTD decreased reovirus RNAs in an otherwise PL background relative to the level for T3DPL. In a T3DTD background, it was evident that M1, S4, and L3 genes from T3DPL could increase virus protein (μ1C) levels. Importantly, when introduced independently, each gene conferred only intermediate levels of RNA and protein relative to the levels of the parental strains, indicating that each gene confers only a portion of the replication advantage that T3DPL exhibits over T3DTD. Nevertheless, all three genes confer a replication advantage for the most oncolytic T3DPL strain relative to replication of the less oncolytic T3DTD strain in a single round of infection.

FIG 4.

S4, M1, and L3 polymorphisms independently contribute to enhanced viral RNA and protein synthesis by T3DPL. (A) L929 cells infected with parental T3DPL or T3DTD and S4, M1 and L3 gene monoreassortant PL-RG or TD-RG viruses at an MOI of 3. At 12 hpi, S4 RNA relative to GAPDH was quantified using RT-qPCR (n ≥ 3). All values were normalized to the value for T3DTD. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) At 12 hpi, Western blot analysis was conducted, and densitometric band quantification of μ1 and σ3, relative to that of nonspecific background band, was calculated and normalized to the value for T3DTD (n ≥ 3).

M1-encoded μ2 confers accelerated core transcription.

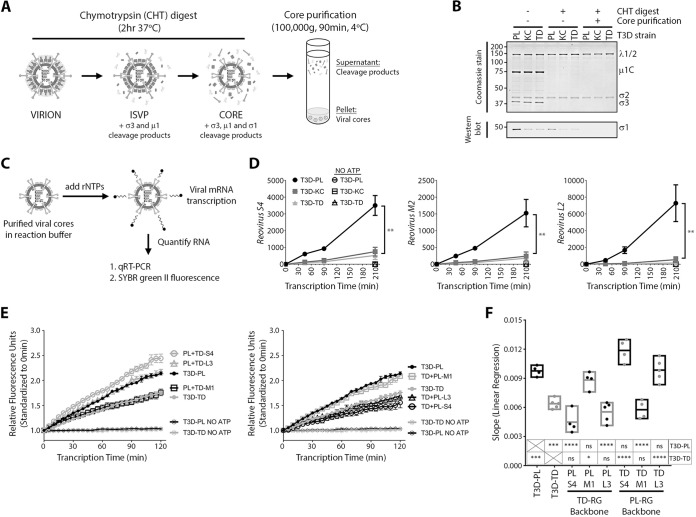

Incoming reovirus cores generate RNAs and proteins that assemble into new progeny cores; these progeny cores then further amplify RNA and protein synthesis. The cyclical nature of reovirus RNA and protein amplifications makes all replication steps interdependent. Accordingly, the observation that virus transcripts accumulate at a higher rate for T3DPL did not directly indicate whether T3DPL cores transcribe more efficiently or whether subsequent steps are enhanced. To directly assess transcription activities of T3D laboratory strains, we therefore performed in vitro transcription assays (Fig. 5A). T3DPL, T3DKC, and T3DTD particles were treated with chymotrypsin (CHT) to generate transcriptionally active cores, purified by high-speed centrifugation, and confirmed to have the characteristic loss of outer capsid proteins (σ1, σ3, and μ1) but maintenance of core inner capsid proteins (σ2, λ1, and λ2) (Fig. 5B). Cores were then subjected to transcription reactions for various time intervals (Fig. 5C), and levels of S4, M2, and L2 viral RNAs were measured by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5D). In vitro-synthesized mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA was used as a spike-in control for sample-to-sample processing variations. Negative-control reaction mixtures lacking recombinant ATP (rATP) produced no increases in RNA levels, confirming that RNA measured in the presence of all four recombinant nucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) accurately reflected de novo core transcription. Furthermore, in vitro core transcription rates were linear, unlike the exponential rates observed during intracellular infection shown in Fig. 2B, reflecting the absence of secondary rounds of amplification that occur during reovirus infection but not in vitro. Importantly, the rates of S4, M2, and L2 viral RNA transcription were significantly higher for T3DPL than for T3DKC and T3DTD. For example, S4 transcripts increased for T3DPL at 16.8 ± 0.9 transcripts/min but at 3.6 ± 0.3 and 2.5 ± 0.3 transcripts/min for T3DKC and T3DTD, respectively. For M2, rates were 7.3 ± 0.5, 1.1 ± 0.2, and 0.9 ± 0.1 transcripts/min for T3DPL, T3DKC and T3DTD, respectively. Therefore, T3DPL has an inherent transcriptase advantage within the viral cores.

FIG 5.

M1-encoded μ2 confers accelerated core transcription. (A) Schematic of chymotrypsin reovirus digestion and viral core purification. (B) Aliquots at various stages during viral core generation and purification were separated by SDS-PAGE, and either total viral proteins were stained using Coomassie dye or σ1 proteins were identified using Western blot analysis. (C) Schematic of reovirus core transcription reactions shown in panels in D and E. (D) Equivalent purified T3DPL, T3DTD, or T3DKC cores were subjected to in vitro transcription reactions as described in Materials and Methods, with either 4 NTPs or 3 NTPs (No ATP). Samples were spiked with GAPDH RNA as an internal control, and RNA extracted and subjected to RT-qPCR for reovirus S4, M2, or L2 relative to the level of GAPDH and normalized to value at the 0 min (input) (n = 3 ± standard deviation; **, P < 0.001). Linear regression analysis determined that (i) the slope of T3DPL differs from that of T3DKC or T3DTD and (ii) the slope of T3DKC does not differs from that of T3DTD. (E) Equivalent purified cores from T3DPL or T3DTD and S4, M1 and L3 gene monoreassortants in an otherwise PL-RG (left) or TD-RG (right) background were subjected to transcription reactions with SYBR green II RNA dye, and fluorescence was monitored at 5-min intervals to monitor increases in RNA abundance over time. Note that in the legend virus labels correspond to the line they are next to and can be used to visualize the hierarchy of highest-to-lowest transcription rates. Fluorescence values were standardized to the value at 0 min (input) (n ≥ 4 ± standard errors of the means). (F) Linear regression analysis was performed on data from panel E (n ≥ 4). Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, with either parental T3DPL or T3DTD as a control data set. * P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, P > 0.05.

Having identified core transcription as a key mechanism for the superior replication of T3DPL, we then asked if any of the three genes that segregated with the large-plaque phenotype of T3DPL accounted for the inherent core transcription advantage. The M1-encoded μ2 protein and L3-encoded λ1 protein seemed the most likely candidates since both λ1 (21, 39, 40) and μ2 (13, 17, 41) have been previously implicated in modulating NTPase activities. The S4-encoded σ3 viral protein is completely removed from cores and therefore was not anticipated to affect core transcription in vitro. Using parental and mono-reassortant viruses described for the experiment shown in Fig. 4, we assessed the effects of M1, S4, and L3 genes on core transcription. Reassortants were treated with CHT, and purified cores were standardized to equivalent numbers of particles. To facilitate more rapid comparison among many samples, we developed an assay that measures RNA levels in real time throughout the reaction, using RNA-binding SYBR green II. Though less sensitive than RT-qPCR, the SYBR II method accurately recapitulated the enhanced transcriptional rates of T3DPL relative to those of T3DTD (Fig. 5E). As expected, no RNA was produced in the absence of rATP (negative control). The T3DTD-derived M1 decreased RNA synthesis rates when placed into an otherwise T3DPL background relative to the rate for T3DPL (Fig. 5E, left). Reciprocally, when the T3DPL-derived M1 was introduced into an otherwise T3DTD background, it was sufficient to restore core transcription to rates similar to those of T3DPL (Fig. 5E, right). When slopes of transcription rates were graphed for three independent experiments (Fig. 5F), it was evident that the M1 gene was necessary and sufficient to confer high transcription rates of T3DPL. These data clearly implicate the M1-encoded μ2 protein as a rate-limiting determinant of reovirus transcription and a dominant basis for the superior plaque size and oncolytic potency of T3DPL.

DISCUSSION

Laboratory strains of T3D exhibit distinct plaque sizes and in vivo oncolytic potentials (6). The distinction between T3D lab strains is important not only for bridging previously contradictory findings between laboratories but also to provide a powerful strategy to identify novel reovirus gene/protein functions and facilitate development of more potent oncolytic reoviruses. The current study reveals that the most oncolytic T3DPL possesses replication advantages in a single round of infection. Two specific mechanisms were identified. First, T3DPL has elevated attachment to cells, attributed to having fewer particles with ≤3 σ1 cell attachment proteins. Second, T3DPL transcribes at rates superior to those of the less oncolytic T3D strains, which is ascribed to polymorphisms in the M1 genome segment encoding the μ2 protein. Accordingly, T3DPL establishes rapid onset of viral RNA and protein synthesis, leading to more rapid kinetics of progeny virus production and a larger virus burst size. These results reveal the importance of rapid onset of infection for reovirus oncolysis.

Previous knowledge about σ1 can help explain why T3DTD and T3DKC strains produce more virus particles bearing too few (≤3) σ1 molecules for attachment to host cells. The S1-encoded σ1 proteins of T3DTD and T3DKC differ from the protein of T3DPL at two positions: A22V and A408T. We along with others previously found that mutations in the σ1 anchor domain (amino acids 1 to 27) affect incorporation of σ1 trimers into the λ2 vertex (22, 42, 43), so we strongly anticipate that the A22V polymorphism plays an important role. The sequence difference at residue 408 is located in the σ1 head domain (amino acids 311 to 455), which interacts with cell surface JAM-A (44, 45). However, since the A408T polymorphism is located distal to the JAM-A binding interface and because binding deficiencies of T3DKC and T3DTD very closely correlated with having virions with fewer than 3 σ1 trimers, we predict that the A22V polymorphism is most important. Future experiments could segregate the two polymorphisms and test the relative importance of each. Interestingly, however, the S1 genome segment was not one of the three segments (S4, M1, and L3) that strongly segregated with a large-plaque phenotype in reassortant and reverse genetics studies (6). Mostly like, because differences in cell binding are only ∼2-fold, they have less impact on plaque size, viral replication, and oncolysis than the polymorphisms in M1, S4, and L3.

The increased transcription rate of T3DPL relative to rates of other T3D strains was clearly associated with polymorphisms in the M1 genome segment. The M1-encoded μ2 protein serves at least two distinct functions: as a structural protein within virus cores, μ2 functions as an NTPase and transcription cofactor; and when expressed during virus replication, μ2 associates with tubulin and other viral proteins to accumulate viral macromolecules at sites of virus replication called factories (14, 46). Increased rates of transcription could reflect two alternative scenarios: either that transcription activity is faster or, alternatively, that a higher proportion of virus cores are capable of transcription at all. By affinity isolation of transcribing cores with bromouridine (BrU) antibodies, Demidenko and Nibert eloquently demonstrated that only a proportion of reovirus serotype 1 Lang (T1L) cores were engaged in transcription during in vitro transcription reactions (47). We favor the first scenario because even at a low virus dose, T3DTD ultimately achieves the same number of infected cells as T3DPL (Fig. 1). In other words, if T3DTD had a higher proportion of cores that were transcriptionally inert, it would be expected that fewer cells would become productively infected. The current discovery that T3DPL μ2 likely has higher rates of transcription provides a new understanding for the impact of μ2. Although NTPase and RNA triphosphatase (RTPase) activities were previously ascribed to μ2 (13, 15), the surprising increase in rate of transcription suggests that μ2 activities are rate limiting during reovirus RNA synthesis. It will be interesting to determine if the polymorphism affects NTP binding, NTPase/RTPase activities, or conformational change during NTP hydrolysis and to relate these activities to RNA unwinding and/or capping using the two T3D strains as a tool.

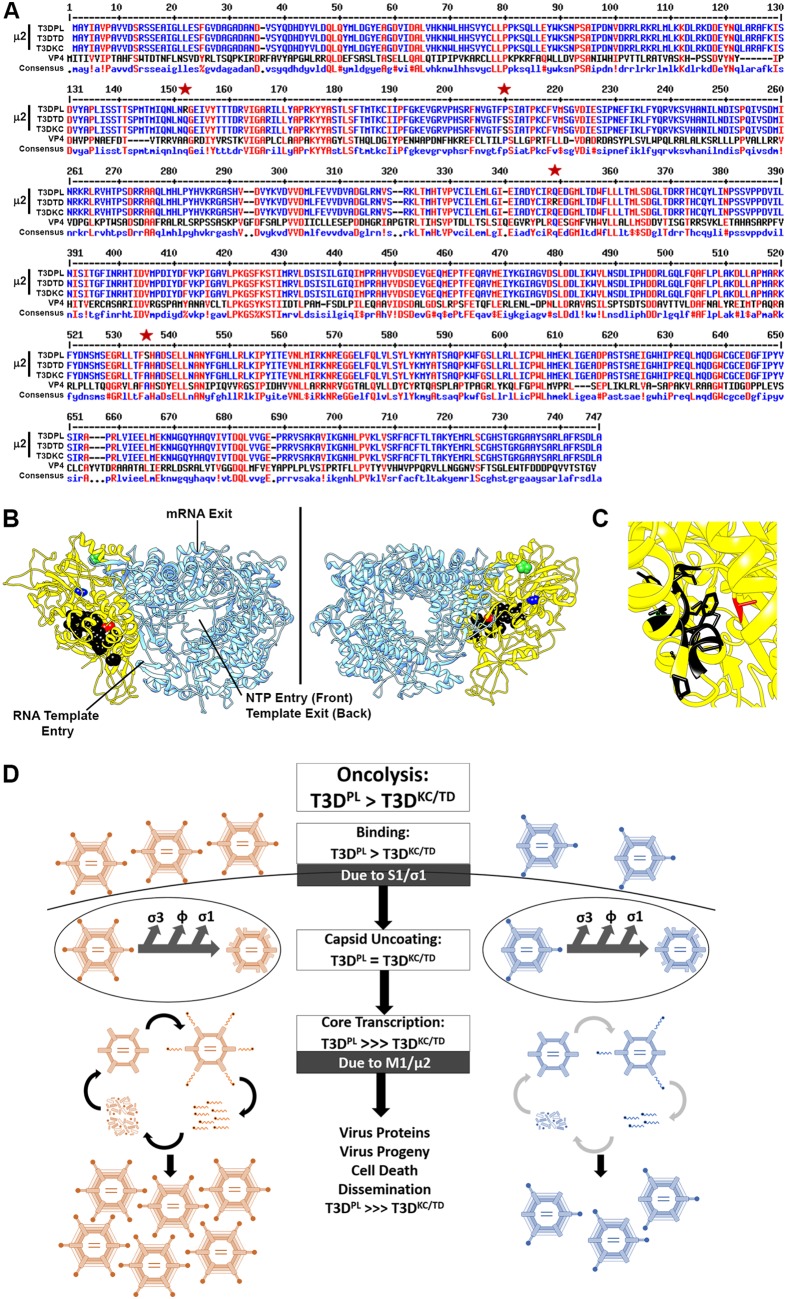

Four polymorphisms exist between μ2 proteins of T3DPL and T3DTD (R150Q, S208P, R342Q, and A528S), but only R150Q, S208P, and A528S are also polymorphic between T3DPL and T3DKC and therefore most likely to be implicated. Although no crystal structures are available for mammalian orthoreovirus μ2, a structure for the putative core protein NTPase of grass carp reovirus VP4, in complex with the polymerase, recently became available (PDB accession number 6M99) (48). Sequence comparison between VP4 and μ2 showed that R150Q, S208P, and A528S μ2 polymorphisms align to regions that are mildly conserved between VP4 and μ2 (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, we felt comfortable mapping these polymorphisms in the structure of VP4 to obtain clues about activity.

FIG 6.

Structure-function analysis of M1 polymorphisms and final model. (A) Sequence comparison between T3DPL, T3DTD and T3DKC μ2 (6), versus grass carp reovirus NTPase/VP4 [GenBank accession number Q8JU68] assembled by multiple sequence alignment by Florence Corpet (52). Red indicates amino acid similarities. Stars indicate the locations of polymorphisms in μ2 between T3DPL and T3DTD and T3DKC. (B) Crystal structure of grass carp reovirus VP3 polymerase (blue) and NTPase/VP4 (yellow) from PDB accession number 6M99. Black represents residues previously described to bear similarity to ATPase domains as described in the text. Green indicates the proposed location of the S208P polymorphism, blue indicates the proposed location of the R150Q polymorphism, and red indicates the proposed location of the A538S polymorphism, extrapolated from panel A. (C) Higher magnification of the proposed ATPase domains and location of the A538S polymorphism. (D) Model describes two mechanisms for enhanced replication of the most oncolytic T3DPL revealed in this study.

Both the R150Q and S208P polymorphisms lie near the NTPase surfaces distal from key polymerase entry and exit portals or from domains previously described to show similarity to motifs of ATPases or NTPase activity site (13, 15, 49) (Fig. 6B). Other laboratories noticed that among different serotypes of reovirus, a proline at position 208 of μ2 produced a filamentous factory morphology while a serine at the same position produced a globular factory morphology (14, 16). The effects on factory morphology are unlikely to contribute to transcription differences in cores. However, variations at position 208 of μ2 were previously found to affect μ2 misfolding and ubiquitination (50). By affecting μ2 stability and folding, it is possible that the 208 variation contributes to transcription differences among T3D strains. The A528S polymorphism, however, lies in close proximity to the ATPase-like domains (Fig. 6C) and is therefore a likely determinant of rapid transcription by T3DPL. Future exploration into residues surrounding A528S should help reveal further the regulation of NTPase and transcription activities. Very surprisingly, when 312 MRV NTPase sequences available in the NCBI database were assessed, position 528 was found in a highly conserved triad of F/Y/L-A/V-H. While the great majority of MRV NTPases contained an alanine or valine at position 528, T3DPL μ2 was the only sequence with a serine, and two other MRV μ2 proteins had cysteines at this position. It would be interesting to determine the effect of introducing serines at position 528 into other MRV μ2 proteins and to understand why evolution of MRV favored alanine and valine instead.

Finally, in addition to M1, both S4 and L3 genes were implicated in enhanced oncolytic activity of T3DPL (6). Our current analysis indicates that both S4 and L3 genes also contribute to the first round of reovirus replication and to postentry but before cell death processes that impact RNA and protein levels. Future studies are needed to determine the precise mechanistic advantages conferred by polymorphisms in these two genes, but studies can now be focused on specific steps early during infection. Altogether this study shows that single amino acid changes drastically affect reovirus replication and supports the idea that strong attention should be paid to the genome and phenotypic characteristics of specific oncolytic virus strains. This study specifically reveals that T3D strains possess inherent cell-independent differences in attachment and transcription. It is possible that a cell-dependent process such as interferon antiviral signaling also contributes to differences between T3D strains and could further affect oncolytic potency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, reovirus stocks, reovirus passaging, large-scale reovirus amplification, reovirus plaque assays, T3D-PL and T3D-TD reverse genetics system, and reassortant reovirus generation.

Cell lines, reovirus stocks, reovirus passaging, large scale reovirus amplification, reovirus plaque assays, T3D-PL and T3D-TD reverse genetics system, and Reassortant reovirus generation are described in Mohamed et al. (6).

IHC and FIA.

In plaque assays, 4% paraformaldehyde was added for 60 min (min) prior to removing overlays and fixation again with methanol. For cell monolayers, paraformaldehyde fixation was used alone. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin (BSA–PBS–0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody (rabbit anti-reovirus polyclonal antibody [pAb]) diluted in blocking buffer at a final concentration of 1:10,000 was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed three time for 5 min each time with PBS–0.1% Triton X-100. Secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer (goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase for immunohistochemistry [IHC] and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 for fluorescence infectivity assay [FIA]) was added and incubated for 1 to 3 h at room temperature. Samples were washed three times for 5 min each time with PBS–0.1% Triton X-100. For IHC, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT; 0.3 mg/ml) (B8503; Millipore Sigma) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP; 15 mg/ml) (N6639; Millipore Sigma) substrates diluted in AP buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) were added, and infected cells were monitored for black/purple staining using microscopy. Reactions were stopped with PBS–5 mM EDTA. For FIA, nuclei were stained with 0.5 μg/ml Hoechst 33352 (H1399; ThermoFisher Scientific) for 15 min, and stained samples were visualized and imaged using EVOS FL Auto Cell Imaging System (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were seeded on coverslips (no. 1.5 thickness). Cell monolayers were washed once with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed twice with PBS, and incubated with blocking buffer (3% BSA–PBS–0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody (mouse anti-σNS 3E10 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568, mouse-anti-σ3 10G10 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647, and rabbit anti-μ2 pAb) diluted in blocking buffer was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Primary monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) mouse anti-σNS and mouse-anti-σ3 10G10 were conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 and Alexa Fluor 647, respectively, using Apex antibody labeling kits as per manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples were washed three times for 5 min each time with PBS–0.1% Triton X-100. Secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer (goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488) was added and incubated for 1 to 3 h at room temperature. Samples were three times for 5 min each time with PBS–0.1% Triton X-100. Nuclei were stained with 0.5 μg/ml Hoechst 33352 (H1399; ThermoFisher Scientific) for 15 min. Coverslips were mounted on microscope slides using 10 μl of SlowFade Diamond (S36967; ThermoFisher Scientific) and visualized using an Olympus IX-81 spinning-disk confocal microscope (Quorum Technologies).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Cells were lysed in TRI Reagent (T9424; Millipore Sigma), and the aqueous phase was separated following chloroform extraction as per the TRI Reagent protocol. Ethanol was mixed with the aqueous phase, and an RNA isolation protocol was continued as per the protocol of the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep kit (RTN350; Millipore Sigma). RNA was eluted using RNase-free water, and total RNA was quantified using Biodrop DUO (Biodrop). Using 1 μg RNA per 20-μl reaction volume, cDNA synthesis was performed with random primers (48190011; ThermoFisher Scientific) and Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (28025013; ThermoFisher Scientific) as per the M-MLV reverse transcriptase protocol. Following a 1/8 cDNA dilution, RT-qPCRs were executed as per the protocol of SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (1725204; Bio-Rad) using a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630 [NP-40], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (11873580001; Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 mM sodium fluoride). For each 12-well plate, 100 μl lysis buffer was used, and volume was scaled up or down according to well size. Following addition of 5× protein sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% SDS, 45% glycerol, 9% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) for a final 1× protein sample buffer, samples were heated for 5 min at 100°C and loaded onto SDS-acrylamide gels. After SDS-PAGE, separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 3% BSA–Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) (blocking buffer) and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies (5 ml of blocking buffer and primary and secondary antibody per minimembrane [7 by 8.5 cm]). Membranes were washed three times for 5 min each time with TBST after primary and secondary antibodies (10 ml wash buffer per minimembrane [7 × 8.5 cm]). Membranes with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies were exposed to ECL Plus Western blotting substrate (32132; ThermoFisher Scientific) (2 ml of substrate per minimemberane [7 × 8.5 cm]) for 2 min at room temperature. Prior to visualization, membranes were rinsed with TBT. Membranes were visualized using an ImageQuant LAS4010 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and densitometric analysis was performed by using ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Note that a “wash” in the above protocol constitutes addition of reagent, gentle rocking back and forth twice, and removal of reagent.

Flow cytometry binding assay.

L929 cells were detached with CellStripper (Corning), diluted, aliquoted (5 × 1010 cells/sample/ml), prechilled at 4°C for 30 min, and bound with normalized virions at 4°C for 1 h. Unbound virus was washed off, and cell-bound virus was quantified using flow cytometry following sequential binding with rabbit anti-reovirus pAb and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488. After secondary antibody staining, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Following a wash with PBS to remove 4% paraformaldehyde, cell pellet was gently resuspended in 500 μl of PBS. Samples were processed using a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) instrument, and data were analyzed using FSC Express, version 5 (De Novo Software). Total cells were gated using forward scatter area (FSC-A) and side scatter area (SSC-A), while single cells were gated using FSC-A and forward scatter height (FSC-H). A minimum of 10,000 total cells were collected for each sample. All steps were performed at 4°C on a microcentrifuge tube rotator, and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (PBS–5% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) was used as the antibody diluent and wash buffer. Prior to fixation, cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. After fixation, cells were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Two wash steps were performed following virus binding and primary and secondary antibody incubation. Note that a “wash” in the above protocol constitutes centrifugation, aspiration of supernatant, resuspension of pellet in wash buffer, centrifugation, and aspiration of wash buffer.

Flow cytometry cell death assay.

Early apoptosis and cell death were measured by annexin V and 7-AAD staining precisely as previously described (51), prior to processing with FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) and analysis with FSC Express, version 5 (De Novo Software). Identical gates were applied to all samples of a given experiment and were applied based on discrimination of the live (annexin V and 7-AAD negative) population.

Agarose gel separation of reovirus.

Purified virions (5 × 1010 virus particles) diluted in 5% Ficoll and 0.05% bromophenol blue were run on a 0.7% agarose gel in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) for 12 h at room temperature, stained with Imperial total protein stain for 2 h at room temperature, destained overnight in TAE buffer, and visualized on the ImageQuant LAS4010 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences)

In vitro reovirus core transcription assay.

Reovirus cores were generated by incubating purified virions with chymotrypsin (CHT) (C3142; Millipore Sigma) at 14 μg/ml for 2 h at 37 C. CHT digest reactions were halted by addition of protease inhibitor cocktail (11873580001; Roche) and incubation at 4°C. Reovirus cores were pelleted by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C, and reconstituted in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8. Transcription reactions were assembled on ice to include 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μg/ml pyruvate kinase (P7768; Millipore Sigma), 3.3 mM phosphoenol pyruvate (P0564; Millipore Sigma), 0.32 units/μl RNaseOUT (10777019; ThermoFisher Scientific), 0.2 mM rATP, 0.2 mM rCTP, 0.2 mM rGTP, 0.2 mM rUTP, and 1 × 1011 virus cores per 150-μl reaction volume. Negative-control samples were set up without rATP. Reactions were allowed to proceed at 40°C and at indicated time points, 40-μl transcription aliquots were added to 400 μl of TRI Reagent LS (T3934; Millipore Sigma) containing 3 ng of mouse GAPDH RNA (in vitro transcribed using T7 RiboMAX [Promega], as per the manufacturer’s protocol). Using 10 μg of glycogen (R0551; ThermoFisher Scientific) as a carrier according to manufacturer’s instructions, RNA was purified and converted to cDNA (28025013; ThermoFisher Scientific) using random primers (48190011; ThermoFisher Scientific), and RT-PCR (1725204; Bio-Rad) was performed to quantify reovirus S4, reovirus M2, and mouse GAPDH. Values were standardized to GAPDH and plotted relative to the value at 0 h posttranscription. For high-throughput transcription assays, reaction mixtures were set up in a similar manner, aliquoted into RT-PCR 96-well tubes, and spiked with a 10× final concentration of SYBR green II (S7564; ThermoFisher Scientific). Relative fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals for 2 h in a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kevin Coombs at the University of Manitoba and Terence Dermody at the University of Pittsburgh for generously sharing their laboratory reovirus T3D lysates, Aja Reiger at the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry flow cytometry facility, Rob Maranchuk at the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology RNAi screening facility, and Stephen Ogg at the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry cell imaging center for valuable technical advice, training, and support. We appreciate all the helpful discussions and suggestions by members of the Maya Shmulevitz, David Evans, Mary Hitt, Ronald Moore, and Patrick Lee laboratories.

This work was funded by a project grant to M.S. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a salary award to M.S. from the Canada Research Chairs, and infrastructure support from the Canada Foundation for Innovation. A.M. received scholarships from an Alberta Cancer Foundation Graduate Studentship, a University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry/Alberta Health Services Graduate Recruitment Studentship, and a University of Alberta Doctoral Recruitment Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antar AA, Konopka JL, Campbell JA, Henry RA, Perdigoto AL, Carter BD, Pozzi A, Abel TW, Dermody TS. 2009. Junctional adhesion molecule-A is required for hematogenous dissemination of reovirus. Cell Host Microbe 5:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zurney J, Kobayashi T, Holm GH, Dermody TS, Sherry B. 2009. Reovirus μ2 protein inhibits interferon signaling through a novel mechanism involving nuclear accumulation of interferon regulatory factor 9. J Virol 83:2178–2187. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01787-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irvin SC, Zurney J, Ooms LS, Chappell JD, Dermody TS, Sherry B. 2012. A single-amino-acid polymorphism in reovirus protein μ2 determines repression of interferon signaling and modulates myocarditis. J Virol 86:2302–2311. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06236-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherry B, Torres J, Blum MA. 1998. Reovirus induction of and sensitivity to beta interferon in cardiac myocyte cultures correlate with induction of myocarditis and are determined by viral core proteins. J Virol 72:1314–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey MC, Strong JE, Forsyth PA, Lee PW. 1998. Reovirus therapy of tumors with activated Ras pathway. Science 282:1332–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamed A, Clements DR, Gujar SA, Lee PW, Smiley JR, Shmulevitz M. 2020. Single amino acid differences between closely related reovirus T3D lab strains alter oncolytic potency in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 94:e01688-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01688-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shatkin AJ, Sipe JD, Loh P. 1968. Separation of ten reovirus genome segments by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Virol 2:986–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jane-Valbuena J, Breun LA, Schiff LA, Nibert ML. 2002. Sites and determinants of early cleavages in the proteolytic processing pathway of reovirus surface protein sigma3. J Virol 76:5184–5197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.10.5184-5197.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liemann S, Chandran K, Baker TS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2002. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, μ1, in a complex with is protector protein, σ3. Cell 108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendez II, She YM, Ens W, Coombs KM. 2003. Digestion pattern of reovirus outer capsid protein sigma3 determined by mass spectrometry. Virology 311:289–304. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yue Z, Shatkin AJ. 1997. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) is regulated by reovirus structural proteins. Virology 234:364–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JA, Schmechel SC, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schiff LA. 2005. Involvement of the interferon-regulated antiviral proteins PKR and RNase L in reovirus-induced shutoff of cellular translation. J Virol 79:2240–2250. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2240-2250.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noble S, Nibert ML. 1997. Core protein μ2 is a second determinant of nucleoside triphosphatase activities by reovirus cores. J Virol 71:7728–7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker JS, Broering TJ, Kim J, Higgins DE, Nibert ML. 2002. Reovirus core protein μ2 determines the filamentous morphology of viral inclusion bodies by interacting with and stabilizing microtubules. J Virol 76:4483–4496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.9.4483-4496.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Parker JS, Murray KE, Nibert ML. 2004. Nucleoside and RNA triphosphatase activities of orthoreovirus transcriptase cofactor mu2. J Biol Chem 279:4394–4403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin P, Keirstead ND, Broering TJ, Arnold MM, Parker JS, Nibert ML, Coombs KM. 2004. Comparisons of the M1 genome segments and encoded mu2 proteins of different reovirus isolates. Virol J 1:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin P, Cheang M, Coombs KM. 1996. The M1 gene is associated with differences in the temperature optimum of the transcriptase activity in reovirus core particles. J Virol 70:1223–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinisch KM, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2000. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 404:960–967. doi: 10.1038/35010041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bisaillon M, Bergeron J, Lemay G. 1997. Characterization of the nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase and helicase activities of the reovirus λ1 protein. J Biol Chem 272:18298–18303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisaillon M, Lemay G. 1997. Characterization of the reovirus λ1 protein RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity. J Biol Chem 272:29954–29957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble S, Nibert ML. 1997. Characterization of an ATPase activity in reovirus cores and its genetic association with core-shell protein λ1. J Virol 71:2182–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohamed A, Teicher C, Haefliger S, Shmulevitz M. 2015. Reduction of virion-associated sigma1 fibers on oncolytic reovirus variants promotes adaptation toward tumorigenic cells. J Virol 89:4319–4334. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03651-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson SM, Antczak JB, Joklik WK. 1994. Reovirus exists in the form of 13 particle species that differ in their content of protein sigma 1. Virology 201:303–311. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. 2012. Transport to late endosomes is required for efficient reovirus infection. J Virol 86:8346–8358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00100-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mainou BA, Zamora PF, Ashbrook AW, Dorset DC, Kim KS, Dermody TS. 2013. Reovirus cell entry requires functional microtubules. mBio 4:e00405-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00405-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danthi P, Holm GH, Stehle T, Dermody TS. 2013. Reovirus receptors, cell entry, and proapoptotic signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol 790:42–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7651-1_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz WL, Haj AK, Schiff LA. 2012. Reovirus uses multiple endocytic pathways for cell entry. J Virol 86:12665–12675. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01861-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danthi P, Guglielmi KM, Kirchner E, Mainou B, Stehle T, Dermody TS. 2010. From touchdown to transcription: the reovirus cell entry pathway. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 343:91–119. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanovic T, Agosto MA, Zhang L, Chandran K, Harrison SC, Nibert ML. 2008. Peptides released from reovirus outer capsid form membrane pores that recruit virus particles. EMBO J 27:1289–1298. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danthi P, Coffey CM, Parker JS, Abel TW, Dermody TS. 2008. Independent regulation of reovirus membrane penetration and apoptosis by the μ1 phi domain. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000248. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2006. Reovirus μ1 structural rearrangements that mediate membrane penetration. J Virol 80:12367–12376. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML. 2006. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nibert ML, Odegard AL, Agosto MA, Chandran K, Schiff LA. 2005. Putative autocleavage of reovirus mu1 protein in concert with outer-capsid disassembly and activation for membrane permeabilization. J Mol Biol 345:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein micro 1 mediates membrane disruption. J Virol 76:9920–9933. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.19.9920-9933.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skehel JJ, Joklik WK. 1969. Studies on the in vitro transcription of reovirus RNA catalyzed by reovirus cores. Virology 39:822–831. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acs G, Klett H, Schonberg M, Christman J, Levin DH, Silverstein SC. 1971. Mechanism of reovirus double-stranded ribonucleic acid synthesis in vivo and in vitro. J Virol 8:684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang CT, Zweerink HJ. 1971. Fate of parental reovirus in infected cell. Virology 46:544–555. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tao Y, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. 2002. RNA synthesis in a cage—structural studies of reovirus polymerase λ3. Cell 111:733–745. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemay G, Danis C. 1994. Reovirus 1 protein: affinity for double-stranded nucleic acids by a small amino-terminal region of the protein independent from the zinc finger motif. J Gen Virol 75:3261–3266. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bisaillon M, Lemay G. 1997. Molecular dissection of the reovirus λ1 protein nucleic acids binding site. Virus Res 51:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coombs KM. 1996. Identification and characterization of a double-stranded RNA- reovirus temperature-sensitive mutant defective in minor core protein mu2. J Virol 70:4237–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nygaard RM, Lahti L, Boehme KW, Ikizler M, Doyle JD, Dermody TS, Schiff LA. 2013. Genetic determinants of reovirus pathogenesis in a murine model of respiratory infection. J Virol 87:9279–9289. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00182-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bokiej M, Ogden KM, Ikizler M, Reiter DM, Stehle T, Dermody TS. 2012. Optimum length and flexibility of reovirus attachment protein σ1 are required for efficient viral infection. J Virol 86:10270–10280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01338-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton ES, Forrest JC, Connolly JL, Chappell JD, Liu Y, Schnell FJ, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Dermody TS. 2001. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell 104:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell JA, Schelling P, Wetzel JD, Johnson EM, Forrest JC, Wilson GA, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA, Stehle T, Dermody TS. 2005. Junctional adhesion molecule A serves as a receptor for prototype and field-isolate strains of mammalian reovirus. J Virol 79:7967–7978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.7967-7978.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coombs KM. 1998. Stoichiometry of reovirus structural proteins in virus, ISVP, and core particles. Virology 243:218–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demidenko AA, Nibert ML. 2009. Probing the transcription mechanisms of reovirus cores with molecules that alter RNA duplex stability. J Virol 83:5659–5670. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02192-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ding K, Nguyen L, Zhou ZH. 2018. In situ structures of the polymerase complex and RNA genome show how aquareovirus transcription machineries respond to uncoating. J Virol 92:e00774-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00774-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eichwald C, Kim J, Nibert ML. 2017. Dissection of mammalian orthoreovirus micro2 reveals a self-associative domain required for binding to microtubules but not to factory matrix protein microNS. PLoS One 12:e0184356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller CL, Parker JS, Dinoso JB, Piggott CD, Perron MJ, Nibert ML. 2004. Increased ubiquitination and other covariant phenotypes attributed to a strain- and temperature-dependent defect of reovirus core protein μ2. J Virol 78:10291–10302. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10291-10302.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shmulevitz M, Lee PW. 2012. Exploring host factors that impact reovirus replication, dissemination, and reovirus-induced cell death in cancer versus normal cells in culture. Methods Mol Biol 797:163–176. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-340-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corpet F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res 16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohamed A, Clements DR, Konda P, Gujar SA, Lee PW, Smiley JR, Shmulevitz M. 2019. Genetic polymorphisms and molecular mechanisms mediating oncolytic potency of reovirus strains. bioRxiv 10.1101/569301. [DOI]